Introduction

One day in early May 1578, the Mughal emperor Akbar (r. 1556–1605) got angry. His anger culminated in an unusual event that was reported in several contemporary Indo-Persian chronicles.Footnote 1 The outcome of the emperor's wrath was considered significant enough to be illustrated in Akbarnama, the official history of his reign composed by his court poet and confidant Abu'l Fazl. Due to the insights it provides into the personality of Akbar, the secondary scholarship on this most lauded of all Mughal rulers has often mentioned the aftermath of his rage on this occasion.Footnote 2 Yet an account of the anger that precipitated and preceded it appears in only one sixteenth-century text, Dalpat Vilas—an obscure chronicle written in a local vernacular rather than in the Persian language favoured by the imperial court.Footnote 3 Its audience was more circumscribed than that of Persian histories as well, for Dalpat Vilas concerned the activities of a local lineage belonging to the Hindu Rajput community.

Rajput warriors had previously ruled over a number of small kingdoms in northern and western India, but had been slowly losing ground since the establishment of the Mughal empire in 1526. Beginning early in Akbar's reign, a series of Rajput leaders were inducted into the Mughal nobility, where they constituted the main group of non-Muslim officers and officials serving the growing empire. These Rajputs provided a much-needed counterweight to the contentious Central Asian and Persian elites at court, along with access to local military labour. Modern Indian historiography regards Akbar's incorporation of Rajputs into the imperial service as an astute move that, combined with his tolerant attitude toward Hinduism and Jainism, made him popular with his non-Muslim subjects and contributed considerably to his success as emperor.

Dalpat Vilas is one of a corpus of broadly historical works—genealogies, dynastic histories, battle accounts—that were commissioned by Rajput lords of the Mughal era, who were generally granted control over their ancestral territories and regarded within them as kings. These Rajput texts have been mined for decades for their chronological and other factual details, yet rarely have other, more cultural, aspects of this literature been explored in depth. Nor have they been fully accepted as legitimate forms of history-writing, with their own logic and their own sensibilities. In this article, I add to the small corpus of scholarship that has begun investigating Rajput texts in search of their representations of the Mughal emperors and their reactions to Mughal rule, along with more general insights into India's martial culture.Footnote 4 In the case of the 1578 incident, the account in Dalpat Vilas is much more detailed than in any of the Persian histories and deviates considerably from them in its interpretation of Akbar's behaviour and frame of mind. The alternative perspective provided by this Rajput chronicle underscores the extent to which we typically depend on texts produced at the imperial centre in reconstructing the court's activities. My first aim in this article, therefore, is to demonstrate that the study of Rajput texts adds another dimension to our understanding of how the Mughal empire operated and how it was experienced. The contrasting narratives of what happened in May 1578 are an especially dramatic instance of difference in the construction of the past.

My second objective here is to further the study of emotions in Indian history and culture—an area of research that is still in its early stages. Dalpat Vilas is one of the few primary sources from Akbar's reign to describe him as enraged, or indeed as possessing notable negative qualities. Even the accounts of his Rajput subordinates routinely describe him as a powerful and righteous king in the traditional Indian mode, as an overlord who could appreciate the bravery of the Rajput lords he had conquered.Footnote 5 Virtually all of the histories composed in Persian by scholars or scribes who were dependent on elite patronage similarly depicted Akbar in highly favourable terms, although there was occasional grumbling about his religious leanings. The ascription of anger to Akbar in Dalpat Vilas is striking not only because this emperor is so widely admired, but also because anger hardly figures in relation to any other ruler in Indian literature. In both the Sanskrit and Persianate traditions, anger was something kings were advised to avoid. The anger displayed by both Akbar and the local Rajput ruler in Dalpat Vilas thus offers us a rare opportunity to analyse the meaning of this emotion in the political culture of sixteenth-century India.

In this initial exploration of anger in the Indian past, I attend carefully to the words used to indicate emotions, since they are neither uniform nor unchanging.Footnote 6 Following earlier historians of emotions working on the Western world, I examine South Asian norms relating to emotions as laid out in Sanskrit literature and treatises. But I place the greatest importance on a careful reading of the incidents of anger that occur in Dalpat Vilas, and how they are embedded in the larger narrative. That is, I ask in which specific social settings and power relations do the rulers get angry and what impact or consequences does their anger have on those around them? Scholars analysing medieval European texts suggest that royal rage could be a performance intended to convey a message, possibly even as parts of larger scripts that were well known to both actor and audience. The notion of embodied and enacted emotions is particularly apt in the case of the kinetic emperor Akbar, who could not read or write and whose ‘understanding of the world was constructed more via the medium of things and sensuous signs and less from abstract concepts and ideas’.Footnote 7 Yet, comparison of Dalpat Vilas's account of the 1578 hunt with several versions of it found in Indo-Persian histories suggests that Akbar's emotions and actions on this occasion were not easily understood by his various audiences, that this was no routine performance of a familiar script. The possibility that there were multiple emotional communities, following the thesis set forth by Barbara H. Rosenwein, the noted scholar of medieval Europe, is one explanation I advance for these divergences in the texts.Footnote 8 For, as we will find, Akbar's anger was not visible to all.

Akbar gets angry in Dalpat Vilas

When Dalpat Vilas's narrative begins, the emperor had been encamped for two weeks in the eastern foothills of the Salt Range, near the Jhelum R. in the Pakistan Punjab, waiting while preparations were being made for a major hunt. In order to trap great quantities of game for the emperor's sport, his men formed a large circle and gradually forced the animals trapped within it into a smaller and smaller space. This type of ring-hunt, called a qamargha in Persian, was a Mughal favourite.Footnote 9 Hunting was an activity popular with the Mughal emperors, often illustrated in court paintings from the reigns of Akbar and Jahangir. The specific forms of Mughal hunts like the qamargha had strong nomadic precedents going back to Central and Inner Asia, where hunting had implications for subsistence as well as for military purposes. Hunting had also long been considered an entirely appropriate sport for kings in India, although hunting for a living was despised. It was a means to publicly display the king's virility and prowess; thus, in addition to its practical benefits in terms of military training, hunting symbolized royal power and showcased the king's paramount status.

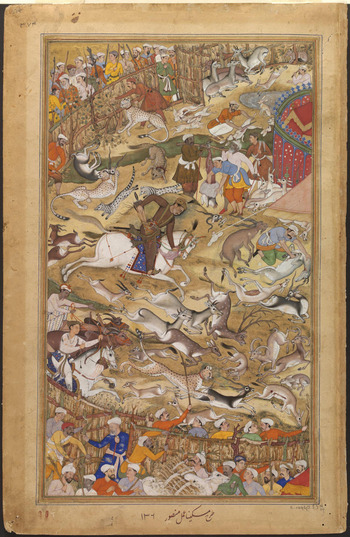

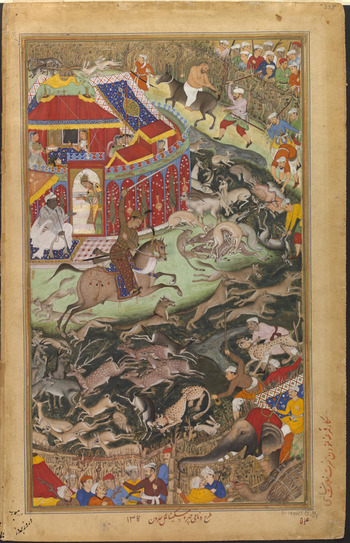

During the Mughal period, large entourages accompanied the emperor on his hunting expeditions, including many nobles and their armed retainers. The scale of the hunts could be enormous, resembling an army on the move. In an earlier ring-hunt of Akbar's in 1567, one chronicler estimated that as many as 50,000 men had been employed to round up the animals. Supposedly the largest qamargha ever held, this 1567 hunt entrapped all the animals within a ten-mile circumference—the captive animals, said to be about 15,000 in number, provided five days of active hunting for the emperor.Footnote 10 The double-page painting that this event's fame merited in the official history has been called the ‘finest hunting scene’ in Akbarnama (Figures 1 and 2).Footnote 11 It shows different kinds of creatures—deer, antelope, foxes, jackals, and the like—fleeing in panic within a circular arena, while Akbar hunts them down with both arrow and sword.Footnote 12 This striking illustration of the emperor's dominance over the world of animals also implies a similar command over humans.

Figure 1. Akbar at the qamargha hunt of 1567, left-hand side. Source: Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Figure 2. Akbar at the qamargha hunt of 1567, right-hand side. Source: Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

By demonstrating their control over massive human and other resources while hunting, the Mughal emperors could awe the populace residing in areas distant from the centres of imperial power. Their hunting expeditions to far-flung corners of the empire were simultaneously exercises in the surveillance of local chiefs, who could be chastised for any failings and brought back into submission.Footnote 13 Abu'l Fazl admits that hunts were a means of gathering intelligence when he states that ‘the wise emperor's constant intention in hunting is to learn of events in the world without the scourge of imperial panoply or the interference of gossipy reporters … so that he may bring down tyrannical bullies and promote obscure persons of worth’. In the case of the 1578 hunt, some recalcitrant chieftains from Baluchistan who had recently been pardoned met the emperor at Bhera, where he proceeded to ‘raise them from the dust of humility’ and reinstate them in the body politic by ‘assigning them places in the hunting circle’.Footnote 14 In an often-cited article, Anand S. Pandian has insightfully read the imperial hunt as a metaphor for the Mughal mode of rule, which relentlessly weeded out any ‘thorns’ in the garden of empire. The Mughal hunt, in Pandian's words, ‘took grandees, warlords and petty potentates as the preeminent objects of its fearful care, cultivating their faithful loyalty through the spectacular exercise of a predatory sovereignty’.Footnote 15

Things went somewhat awry during the May 1578 qamargha, however, which is as well known as the celebrated hunt of 1567 but for different reasons. It begins with an episode of anger, in the narrative of Dalpat Vilas.Footnote 16 On the second day of hunting, Akbar had as usual gone out on his own in the morning—that is, without any of his nobles in accompaniment.Footnote 17 When he returned to the temporary encampment where the court was staying, his lords (ṭhākur) were playing kabaḍḍi, a game involving the tagging of opponents for which the players wore bathing clothes (potiyā). The lords, who included both Muslims and Hindus, did not immediately rush back to their tents to change into court dress, thinking that the emperor might join them in play.

This proved to be a major miscalculation. Instead of joining in their sport, Akbar headed for the river and entered the water; afterwards he headed to the encampment's place of assembly (darbār). Most of the lords had in the meantime put on their clothes and paid respects to the emperor, but not the Solanki clansman Dan. (Dan, like most of the men figuring in this episode, was a member of the Rajput warrior community.) When Dan finally showed up to attend to Akbar, the emperor was furious, as the text tells us:

Meanwhile Dan [the Solanki] came there. Then the Emperor asked, ‘Where were you until now? Why didn't you come [more quickly]’? He said, ‘Sir, I had to put on clothes for the sake of propriety (adab), so I erred and got delayed’. Then the Emperor got angry (khijiyā) and flogged him four to five times. Just then, Prithidip [Kachwaha] arrived and the emperor said to him, ‘Where were you’? Then he said, ‘Emperor, your good-health!Footnote 18 My aidesFootnote 19 didn't let me come’.

Then the Emperor flogged him seven-eight times. And he summoned the [Kachwaha boy's] aides and had the aides beaten. He said to them, ‘Why didn't you bring him’? Then they said, ‘His mother's brother wouldn't allow him to come. As soon as he was dressed, he fell down into a ditch. Then his mother's brother said, “Let him play”. So, it's not our fault. Emperor, your good health! His mother's brother didn't let him come.’Footnote 20

Akbar's wrath did not abate, despite the whipping of two Rajputs who had been tardy in appearing, as well as some of their retainers. He next turned his attention to a more consequential target—the Kachwaha boy's uncle:

Then, after summoning Prithidip's mother's brother, His Majesty got angry: ‘Why didn't you let him come’? Then he said, ‘Emperor, your good health! How would it be fitting that I should stop him from coming to your excellence's presence’? Then the Emperor ordered a whip be used. When a cowherder had whipped him once and stood waiting, just then the mother's brotherFootnote 21 drew a dagger and stabbed himself. Once, twice, three times he thrust the dagger.

Meanwhile, the Emperor was angry and said, ‘Kill him, kill this bastard (harāmjādā)’! And he asked for an elephant; he asked for the elephant that a tax collectorFootnote 22 had presented as a gift. The elephant would not advance [to trample the uncle who had stabbed himself]. Then the emperor became even more angry and went into his quarters.Footnote 23

We witness an escalation of events in this scene. The first man who was tardy in attendance, thereby incurring Akbar's anger, was punished with four or five lashes of a whip; the second one who showed up late merited seven or eight lashes, even though he was apparently still a boy. Akbar then spread the blame for this second Rajput's tardiness to his adult caretakers, and then finally to the young man's uncle. After one lash of the whip, however, the uncle retaliated not by trying to harm the emperor but rather by harming himself.

A better-known case of a Rajput lord stabbing himself with a dagger occurred a few years later in 1586, when the high-ranking Rajput lord Bhagwant Das of the Kachwaha family did so after his assurance of safety to an enemy was abrogated by Akbar.Footnote 24 The threat of suicide by dagger was a tactic used by the bards of western India, who often acted as sureties for safe passage of a caravan or the well-being of a hostage. It was effective in dissuading wrongdoers because bards were thought to possess sacred authority. Although Rajputs did not share that sacred character, they would have been familiar with the bardic practice of harming their own bodies as a form of protest. By employing it, Bhagwant Das could testify to the sincerity of his offer of refuge to an enemy and thus salvage his honour, as well as signify his grievance to the emperor who had repudiated his promise. When the tardy young Rajput's uncle stabbed himself in 1578, it was likely also a matter of honour, in an unspoken reproach for Akbar's injustice.

High-ranking nobles were seldom publicly injured or humiliated, unless they committed egregious breaches of etiquette such as appearing at court in an intoxicated state. Instead, the emperor sometimes verbally censured his nobles, and if they did not obey his commands to join a particular theatre of war or if they prosecuted a campaign poorly, he might take away territory or reduce their rank at court. However, the most common expression of his displeasure with elite officers was to forbid them from attending court. Physical punishment or public humiliation was generally reserved for subordinates at lower ranks, like Hamid Bakari, a minor court attendant, who had shot an arrow at a courtier during the qamargha of 1567.Footnote 25 When Akbar was informed of this, he handed over his sword to a nearby officer and told him to kill Hamid Bakari right there and then. Hamid miraculously remained unscathed even after two attempts to smite him, however, and so the emperor spared his life. But, according to the official history, ‘in order to teach a lesson to other immoderates, his head was shaved and he was mounted on an ass and paraded around the hunting ground’.Footnote 26 The public shaming of this errant attendant was clearly intended as a deterrent; it was noteworthy enough to be included in both illustrated manuscripts of Akbarnama.Footnote 27

If court histories give an accurate picture overall of the severity of Akbar's punishments, it may be that his outrage at the lateness of the Rajputs at the 1578 hunt was excessive, even by the standards of the day. Certainly, the prideful readiness of Prithidip's uncle to hurt and even kill himself only served to further infuriate Akbar, so much so that the emperor demanded that an elephant should trample him to death right then and there. Father Monserrate, a Jesuit missionary who spent two years at Akbar's court, describes this as a punishment for those committing capital crimes.Footnote 28 Dalpat Vilas's insinuation that Akbar had been cruel and unjustified in his treatment of these Rajputs might therefore reflect a viewpoint shared by others in imperial service. In any case, the uncle's refusal to submit to Akbar's chastisement was compounded, according to this text, by the elephant's refusal to obey the emperor's order. As is well known, Akbar prided himself on his ability to control war elephants, yet here again his mastery over others—whether human or non-human—was being challenged.

What happened later that evening in May 1578 suggests that the emperor regretted his actions. After everyone had retreated to their separate tents in consternation for some hours, the Kachwaha lord Man Singh, who had been away in Ajmer, arrived at the hunting site to join the entourage.Footnote 29 The emperor ordered Man Singh, his closest and most trusted Rajput subordinate, to take charge of the situation, presumably because other Rajputs were involved:

When Man Singh KunwarFootnote 30 touched the Emperor's feet [in greeting], he said to Man Singh, ‘See what this Rajput bastard did–he stabbed himself in the stomach. If he's living, then get the wound bound up. If he's died, then provide wood and a shroud’.Footnote 31 When the Emperor commanded thus, Man Singh carried out the Emperor's command and went to look for him. And, from behind, the Emperor grumbled angrily (bajariyā).

In other words, Akbar used his best friend among the Rajputs as an emissary to find out what had happened to the prideful Rajput and offer the appropriate assistance, in a form of amends for his earlier anger. Unfortunately, while Man Singh was checking on him, the injured man died.Footnote 32

Understanding anger in the Indian context

This is by no means the end of the story of Akbar's hunt, as matters soon took a dramatically different turn. But I would like to halt the progress of the narrative momentarily, in order to turn to two other issues: the question of how Indian tradition has conceptualized anger in general and, more specifically, the role of anger in Dalpat Vilas. I have been discussing anger thus far as if it were an unproblematic, universal category and, indeed, it is often considered to be one of the basic emotions that are shared by all humans, something innate and natural.Footnote 33 The universalist understanding of anger is facilitated by the fact that language used to describe the experience and manifestation of anger can often be understood across cultural boundaries and the expanse of time. Zoltán Kövecses argues, for instance, that metaphors in English, Hungarian, Chinese, and Japanese—four unrelated languages—indicate that ‘all four cultures seem to conceptualize human beings as containers and anger (or its counterparts) as some kind of substance (a fluid or gas) inside the container’.Footnote 34 He calls this the ‘pressurized container’ metaphor and suggests that physiological responses to anger may contribute to the similarity in conceptual metaphors. Yet, even if we agree that many cultures share similar ways of talking about anger, we need not concede that emotions are innate and therefore uniform across cultures. Observations of people around the world have amply documented differences in the deployment of anger—that is, when and where and why it is permissible to be angry, and in what manner—as well as variations in the meaning or value placed on this emotion. Anger, like any other emotion, is shaped by its social context and is thus potentially highly variable according to the time, place, and other factors.Footnote 35

Recent approaches to the history of the emotions have sought to bridge the conceptual division between the interior experience of an emotion and the external expression of it. That is, instead of regarding the mental feeling as separate from its bodily manifestation (in a smile, frown, or speech-act, for example), scholars are increasingly viewing emotion as a combination of both. As Monique Scheer argues ‘emotions are something people experience and something they do. We have emotions and we manifest emotions’ (emphasis in original). This insistence on the embodiment of emotions in physical form situates them firmly in a social setting within which they interact and circulate.Footnote 36 Scheer's influential approach to emotions as practice, drawing on Pierre Bourdieu's concept of habitus, focuses much attention on practices of the body, opening up a vast new range of source materials for emotion studies. Like Scheer, Margrit Pernau points out that emotions are circular in nature, ‘moving in both directions–from emotions felt to emotions expressed, certainly, but also from the expression and performance as well as the interpretation of emotions back to how a certain emotion is felt’.Footnote 37 The emotional-practices approach cannot be fully implemented in studies of single texts such as mine here, but its attention to bodily processes helps deepen our analysis.

Interest in South Asia's emotional past has been late to develop, but it is now growing dramatically.Footnote 38 This scholarship is still appearing primarily in article-length form and much of the focus continues to be on love—a topic of long-standing popularity—along with a newer interest in nostalgia.Footnote 39 In a welcome move, some of the newest work on precolonial South Asia explores the emotional landscapes revealed in music, paintings, and gardens, as well as in poetry.Footnote 40 However, research on anger is mainly confined to a few scholars working on South Asia's recent past or its present, and not its more distant past.Footnote 41 In one example, Imke Rajamani explores Bollywood films, in which ‘anger in the popular public sphere’ had earlier been regarded ‘as a bad emotion—an uncontrollable passion that leads its bearers to commit inexcusable crimes against law and morality’.Footnote 42 The situation changed in the 1970s and early 1980s, as the image of the angry young man, personified by the actor Amitabh Bachchan, captivated the world of Hindi cinema. The angry young man's rage was directed against corrupt politicians and greedy businessman against whom he had to fight; the popularity of films of this kind led to an expanded conception of anger that acknowledged the virtue of this emotion when it targeted social injustice, rather than viewing anger as entirely negative in nature.Footnote 43

Just as in Hindi films before the 1970s, so too did the Sanskrit literature of ancient and medieval India discourage the public display of anger. The aversion toward expressions of anger had religious roots, for desire and other strong emotions were identified in much ancient Indian thought as the culprits that bound humans to the relentless wheel of birth and rebirth. In the words of the celebrated Bhagavadgita, a sermon by the god Krishna on the eve of battle:

The means to the supreme religious goal was by cultivating detachment and dispassion, by ridding oneself of desire and anger.

Rulers, for reasons of both righteousness and pragmatism, were expected to conduct themselves in a dispassionate manner. Ancient Sanskrit legal texts stressed that, in order to be successful, kings must avoid addiction to kāma (desire or pleasure) and krodha (anger or wrath), and strive for self-control.Footnote 45 The premier work on statecraft, the Arthasastra, went so far as to state that ‘this entire treatise boils down to the mastery over the senses’.Footnote 46 Similarly, in India's famous martial epic, the Mahabharata, king Yudhishthira is advised that a ruler's behaviour should ideally be guided by self-restraint: ‘The Gods and the highest seers said to him: Do without hesitation whatever is Law: having restrained yourself—having forsaken your likes and dislikes, acting the same toward every person, having put desire and anger and greed and pride far off and away.’Footnote 47

Here, greed (lobha) and pride (mān) also figure as repugnant qualities, and we sometimes get references to other feelings that should be repressed or set aside, but kāma and krodha are the most frequently cited emotions to avoid.Footnote 48 Elsewhere in the epic, Yudhishthira's wife Draupadi chastises him for not being furious at his rival cousins, who unfairly forced them into exile in the forest. Yudhishthira, the son of Dharma (righteousness), responds with a discourse on the dangers of anger and goes on to extol the importance of self-mastery through the practice of kṣamā—forbearance or forgiveness.Footnote 49 By the early medieval era, behaving in a disciplined manner was enjoined not only for the rulers but for all members of the upper class.Footnote 50 The emphasis in Sanskrit courtly literature was on courtesy, modesty, aesthetic refinement, and comportment: restrained qualities that are missing from the action-oriented and violent world of the vernacular Rajput chronicle.

This is not to say that anger was absent from ancient or medieval Sanskrit narratives, but the men described as angry were primarily warriors in the heat of battle and not rulers per se. Take the example of Book 10 of the Mahabharata, in which we get the most horrific episode of violence resulting from anger in the entire epic. This is when Asvatthama, fighting on the side of the Kauravas, slaughters the sleeping warriors of the Pandava army in order to avenge the slaying of his father Drona. Asvatthama's krodha wells up from his inner depths,Footnote 51 causing his eyes to get bloodshot and bulge out—an example of the ‘pressurized container’ metaphor described by Kövecses.Footnote 52 The effects of Asvatthama's rage are compared to what happens when a fire blows through dry grass, and his own body too is ‘burnt up with rage’.Footnote 53

The descriptions of anger here and elsewhere in India's foremost martial epic tend to be superficial, repetitive, and short—in other words, not very complex. These images of anger composed in a time and place far distant are familiar to us even today: we too burn with the anger that blazes through us, and our eyes can also turn red from rage. This makes it easy to dismiss anger as an object of analysis, for what, one might ask, can really be said about it? The contrast with our scholarly attitude toward kāma is quite striking. We might consider ‘desire’ to be a human universal, but not so in the case of other English words we use for kāma: ‘pleasure’ (and not only sexual pleasure) and ‘love’. Certainly in the case of romantic love, it is not difficult to accept that an emotion can be socially constructed, that it might vary depending on when, where, and whom.Footnote 54 And we appreciate that love in South Asia comes in an array of ‘idioms’, to use Francesca Orsini's phrasing: not just the concept of kāma, but also ishq, prem, and viraha. Footnote 55

Natyasastra, the foundational text of Indian drama, does acknowledge that anger comes in different shapes and forms, even though it associates anger most closely with warriors and warfare.Footnote 56 In this treatise, the main focus is on rasa or ‘taste’—an emotional state enacted by a character within a dramatic performance. These ‘tastes’ were based on one of the eight stable (sthāyi) emotions, or bhāva: desire (rati), amusement (hāsa), grief (śoka), anger (krodha), determination/enthusiasm (utsāha), fear (bhaya), revulsion (jugupsa), and amazement (vismaya).Footnote 57 These are all feelings that can be enacted visibly and therefore performed on stage, so we cannot take them as a complete list of the important emotions recognized in Indian thought. Later on, when aesthetic theory was applied to literature rather than drama, other sentiments that do not manifest themselves as obviously in physical form—like motherly love or peacefulness—also came to be regarded as emotions.Footnote 58

Despite its essentially performative orientation, the Natyasastra remains valuable as our primary source of information on ancient conceptions relating to the emotions. It provides ‘a comprehensive theory of emotion’, in Vinay Dharwadker's opinion, and ‘unites the arts by placing emotion (as distinct from, say, perception and judgment) at the centre of aesthetic theory and practice’.Footnote 59 In discussing krodha or anger, Natyasastra lists four types of anger differentiated by the person to whom it is directed—enemy, teacher, lover, or servant—as well as a fifth category of simulated anger. Anger at an enemy was to be expressed on stage with arched eyebrows, the biting of lips, the rubbing of hands, and the actor's looking at his own arms and those of the enemy.Footnote 60 The rasa or ‘taste’ associated with the emotion of anger is the violent or wrathful, raudra, which is ‘produced by battles, striking, wounding, killing, cutting and by violence, etc.’ and ‘is to be acted by using various weapons and cutting off heads, arms, etc.’.Footnote 61 While it acknowledges that the emotion comes in various shades, the first and foremost context for anger in the Natyasastra is that of violence and warfare. Others may also feel anger, but the quintessential experience of it is the warrior's.

Emotion of anger in Dalpat Vilas

If Indian rulers, as distinct from warriors, were indeed seldom depicted in a state of wrath in pre-modern literature, as I have argued, how do we explain the vignette of the angry Akbar in Dalpat Vilas? Why might Dalpat Vilas be rather unusual in its depiction of anger—a quality thought to be regrettable in elite Indian culture? For one thing, it is written in the vernacular rather than in Sanskrit, at a time when historical texts written down in a North Indian vernacular were still relatively rare. John D. Smith identifies Dalpat Vilas as the oldest extant chronicle in Middle Marwari (a form of Rajasthani), the same language used in the more famous Khyat by Munhanot Nainsi.Footnote 62 Secondly, it is also unusual in being composed in prose instead of verse, which was far more widespread in precolonial Indian literature. As a prose work, Dalpat Vilas foregoes the fulsome praise and elaborate embellishment that is typical of the courtly mahākāvya poems, composed in both Sanskrit and classical Hindi. In contrast, Dalpat Vilas favours a matter-of-fact tone, straightforward narration, and a detailed account of some events. The quantity of detail on places and people sets the prose Dalpat Vilas apart from the more elaborate courtly literature in verse and has led to speculation that the author was present at the major events covered.Footnote 63 The emphasis on extensive reporting gives the text a more historical feel and differentiates it from the eulogies to their patrons that were the standard fare of court poets. Yet is important to note that Dalpat Vilas never presents its protagonist Dalpat in a bad light, no matter how much unsavoury activity by other high-ranking men it describes.

As its title suggests, Dalpat Vilas (Adventures of Dalpat) was intended to recount the life of Dalpat Singh, a Rajput of the Rathor lineage based in Bikaner who reigned briefly over the Bikaner kingdom in 1612–13.Footnote 64 He was soon deposed by the Mughal emperor Jahangir due to his refusal to obey commands and was killed by another noble shortly thereafter.Footnote 65 Because the Bikaner throne was passed on to Dalpat's brother and his descendants, Dalpat has not received much mention in later historical traditions from western India. This may explain why only one manuscript of Dalpat Vilas survives, possibly a copy made in the 1650s or 1660s, which was preserved in the library of the Bikaner royal family.Footnote 66 That is, this text presumably composed for Dalpat Singh likely did not circulate outside a small circle, and was of little interest to Rajput audiences in general. The sole extant copy is incomplete, unfortunately, for it ends abruptly in the summer of 1578 when Dalpat was only 13 years old.Footnote 67 This means that Dalpat's male relatives and other older men often play a bigger role in the episodes narrated in the chronicle than Dalpat does himself, since he was still so young. However, most of the episodes do pertain to Dalpat in some fashion—he was present at Akbar's hunting camp in 1578 and witnessed the events that transpired.

We do not know when Dalpat Vilas was written nor who wrote it—details that are often provided in the final pages of Indian manuscripts, sadly missing in this case. But the best estimates place its composition between 1595 and 1600—a time when Dalpat's father would still have been the Bikaner king.Footnote 68 Dalpat Vilas is a departure from the norm for early modern Rajasthani or Hindi (Brajbhasha) historical texts in a variety of ways, beginning with the fact that its protagonist was still a young lord rather than a king or lineage head. At 44 folios in length,Footnote 69 Dalpat Vilas also falls into a class of its own among prose genres in Rajasthani—it is much longer than the vāt or tale (typically an episode pertaining to a single individual) and much shorter than the khyāt or chronicle (typically an extensive work covering one or more dynasties).Footnote 70 Nor does the unknown author appear to have been a member of the bardic communities who are most often associated with the composition and recitation of both prose and verse works commemorating Rajputs.Footnote 71

Dalpat Vilas's early date accounts for much of its historiographic significance, for few other texts from Rajput courts cover the 1570s, the critical period when emperor Akbar was consolidating his power in Rajasthan and Gujarat.Footnote 72 Dalpat's lineage, the Rathors of Bikaner in north-western Rajasthan, became staunch supporters of the Mughal empire in 1570, just two years after Akbar's infamous siege and sacking of the formidable Rajput stronghold at Chittaur—an act that amply demonstrated the extent of Mughal might. Although the Bikaner Rathors never attained the prominence of the Kachwahas of Amer, who had allied themselves with the Mughals as early as 1562, they were among the most influential of Akbar's Rajput subordinates.Footnote 73 In Dalpat Vilas, members of the Bikaner royal family are depicted as quite mobile, often being summoned to Akbar's presence wherever he might be holding court at the moment. At other times, they were stationed outside their home territory guarding a fort or on a military campaign at Akbar's behest, helping the emperor to expand his realm. Our incomplete manuscript of Dalpat Vilas only narrates events up to the middle of 1578; at that point in time, Akbar had control over much of northern and western India and had made inroads into eastern India.Footnote 74

Intended for a warrior audience, one might expect Dalpat Vilas to be replete with examples of fuming fighters yet that is not the case. Only two individuals are said to be angry more than once and they are the two most powerful men appearing in this chronicle: the Mughal emperor Akbar and Dalpat's father Raja Ray Singh, who ruled the Bikaner kingdom in subservience to the Mughals. Ray Singh had fought on Akbar's behalf in both Gujarat and Rajasthan before he ascended the Bikaner throne in 1574, and in later years would become one of the greatest lords in the Mughal empire. It is no coincidence that anger is primarily the preserve of these two rulers—a point to which I will return. Overall, however, Dalpat Vilas is strikingly devoid of affect, of feelings and moods. Its prose is simple and even pedestrian—full of short declarative sentences with few adjectives or adverbs and frequent repetition of verbs of motion. The following passage is typical of the chronicle's literary style:

The Emperor conquered Surat, entrusted it to Kilac Khan, and departed for Fatehpur Sikri. He left Ajij Koko in Ahmadabad and set out for Sikri. Ray Kalyanmal and Kunwar Ray Singh were in Jodhpur and went and met with the Emperor in Ajmer. There he gave Kalyanmal a robe of honour (sirpāv), an elephant and horses, and sent him to Bikaner. The Emperor proceeded on to Sikri.Footnote 75

Men go places, they say or do things, and then they go elsewhere—that is the general course of the narrative. Seldom is anyone pleased or happy in this chronicle, although they occasionally experience fear; as one might expect, the persons who are feared are always higher-ranking than those who are afraid. But it is noteworthy that anger is the most prominent of the few sentiments appearing in the almost barren emotional terrain of Dalpat Vilas.

Here I need to be more transparent about my own interpretive practices, for I am accepting only two terms in the original text as equivalents of the English anger or angry. There are several other words that indicate similar but less intense states: being displeased at, offended by, hostile toward, or thinking badly of someone.Footnote 76 The primary word I translate as getting angry is the verb khijaṇau/khījaṇau, whose modern Hindi variant (khījnā) implies irritation and vexation.Footnote 77 Yet it is clearly something stronger in Dalpat Vilas, where it is the most frequent of the anger-like terms and the only one used in reference to emperor Akbar's feelings toward the Rajputs he had whipped. The word is also twice applied to the Bikaner king, Dalpat's father Raja Ray Singh, when he is so infuriated by the behaviour of Kesav, a warrior attached to his brother Ram Singh, that he orders his men to attack and kill Kesav:

The Raja began mustering his troops for the imperial paymaster. The Raja, Turasam Khan, and Said Hasim all sat down and started watching. When Ram Singh's troops were being reviewed, Ram Singh's other Rajputs [dismounted], held onto their horses, performed the taslīm salutation,Footnote 78 and came back; but Kesav remained mounted on his horse. He didn't get down, didn't do the salutation. Moving forward, he made his horse gallop. The Raja observed this. Watching, the Raja got infuriated (khījiyā), so much so that he would have had him killed right there.Footnote 79

By refusing to dismount and salute the imperial paymaster, who was inspecting Raja Ray Singh's troops to ensure that they met the expected standards, Kesav displayed disrespect towards Bikaner's Mughal overlord and simultaneously undermined Ray Singh's authority. As a result, Ray Singh experienced an anger accompanied by violent intent, denoted by the verb khijaṇau/khījaṇau, just as in the case of Akbar and his Rajput lords.Footnote 80

Elsewhere in the chronicle, the second term that I translate as angry is used to describe the rage Raja Ray Singh felt toward his son Bhopat.Footnote 81 Relations between father and son had been tense for some time when the following episode occurred:

Then the Raja became furious (rīsāṃṇā) at Kunwar Bhopat. Then the Raja dispatched the Rani to summon Bhopat. Then the Rani proceeded to Bikaner, consoled Kunwar Bhopat, and fed him liquor; and when he was drunk, she seated him on a cart, and took him to the Raja. Just as Bhopat touched the feet of the Raja, the Raja began to hit him on the back with a staff, with his own hand. Then Rani Jasvantde used her hands as a shield, but the blow of the stick hit her hands. Then her bangles were ruined. Meanwhile, the Munhata (minister) spoke to the Raja and intervened [so that] Bhopat was let go.Footnote 82

Prior to this scene, Bhopat had been dispatched to Bikaner town to take care of a problem for the raja. Although he had carried out the mission well, afterwards, Bhopat indulged in drink and games rather than returning promptly to Jodhpur, where his father was then stationed. When the queen brought their son to see him, the extreme anger that Ray Singh felt toward Bhopat incited him to violence, even at the cost of harming his wife along with his son.

Ray Singh Rathor was a successful leader, who governed Bikaner from 1574 until his death in 1612, and a valued military officer in the Mughal army, serving in areas as far apart as the Punjab, Bengal, Baluchistan, Sind, and the Deccan.Footnote 83 Despite his illustrious career and extensive cultural patronage, Dalpat Vilas paints an unfavourable picture of Ray Singh as an unpleasant man who was often harsh and abusive. Raja Ray Singh's displeasure is typically focused internally, on his own family, in this chronicle, rather than being directed outwards, towards his Rajput rivals or the empire's enemies. In addition to abusing his son Bhopat, the raja was also overbearing in his dealings with his own brothers, whom he would verbally chastise if their behaviour did not meet his approval. When furious at his kin, the raja might even send armed men against them, in order to ensure their obedience.

In Raja Ray Singh's angry outbursts, we witness resonances of Akbar's rage during the qamargha. The anger that was aroused in the emperor by the offence of insufficient subservience was repeatedly given expression through the public whipping of the offenders. Royal rage and corporal punishment are thus closely linked, with the former leading rapidly to the latter, as the indignant ruler displayed his displeasure by exercising his right to punish others. Like the furious emperor, the irate Bikaner king Ray Singh ordered the insolent Rajput warrior Kesav to be killed immediately and tried to beat his son for neglecting his princely duties. In Dalpat Vilas, anger was an emotion associated with rulers that could lead to physical harm and even death for the targets of their emotion.

We could read the narratives relating to both king and emperor as critiques of their lack of self-control and their excessive anger, for they clearly do not possess the kind of detachment and restraint that Sanskrit literature lauded. From our viewpoint today, both rulers acted in an arbitrary and unjust manner, displaying their flawed and even tyrannical characters. The Bikaner raja, who figures in much more of the chronicle than the Mughal emperor, is explicitly said to be feared by those around him, as was his father.Footnote 84 Even though the words ‘fear’ or ‘afraid’ appear fewer than ten times, fear is still the second most frequently mentioned emotion in Dalpat Vilas.Footnote 85 It is generally used to explain why a person of inferior status did not take some desirable action, due to his fear of how someone more powerful might react. Fear was aroused not only by rulers, but also by men like Dalpat's unruly and violent uncles whom his personal retinue was afraid to face in battle—it was the unpredictable and potentially extremely dangerous responses of kings and leading warriors that struck terror into the hearts of others.

Instead of simply dismissing the actions of Akbar and Ray Singh as cruel and despotic, a more complex reading of the chronicle would note the ways in which they purportedly used royal anger to consolidate power—the late sixteenth century was a time when power was getting centralized not only in the Mughal emperor's hands, but likewise in the hands of increasingly powerful clan chiefs like Raja Ray Singh. In contrast to the more egalitarian brotherhood that had earlier prevailed among the Rajput clans of western Rajasthan, Ray Singh and his counterparts elsewhere in Rajasthan favoured a hierarchical form of governance with a raja at its apex. This was congenial to the Mughals, who preferred to deal with a clearly designated leader, but since the Bikaner Rathors had submitted to the empire less than a decade earlier, Ray Singh's position was still tenuous at the time of the 1578 hunt. This meant that he could not permit practices that might have been tolerated in the past, like various incidents of looting by his brothers and Kesav's failure to be respectful to an imperial official, if he were to retain the emperor's favour. In order to maintain his status as ruler of Bikaner, the raja had to rein in his brash family and followers by modifying their behaviour.

Similarly, rather than viewing Akbar as an impulsive tyrant who hurt people with little reason, we might instead regard Akbar as engaged in the disciplining of his nobles. As André Wink has pointed out, Akbarnama repeatedly employs the hunting and taming of wild beasts such as elephants as metaphors for the taming or civilizing of Akbar's rebellious Central Asian nobles.Footnote 86 Both Wink and Harbans Mukhia—no doubt influenced by Norbert Elias's emphasis on the role of court etiquette—have noted that a similar desire for control over his subordinates led to the increasingly formal procedures and protocols at Akbar's court.Footnote 87 Pandian, in his casting of Mughal rule as a form of predatory care, also emphasized their disciplining and punishment of insubordinate underlings. We could, in that light, interpret the whipping of the tardy nobles as an effort by Akbar to enforce new norms of obedience and deference.

In the view of Dalpat Vilas, therefore, anger is a tool for powerful lords to wield, as a means to regulate the speech and actions of their subordinates. Just as emperor Akbar sought to control the actions of his underlings, so too did Raja Ray Singh, the second most powerful man appearing in Dalpat Vilas, strive to regulate the conduct of his family members. Furthermore, royal rage seemingly served as an explanation for the ensuing act of punishment involving physical violence. Punishment was central to the king's role in Sanskrit thought, for, without his intervention, the world would devolve into a state of chaos where the bigger fish would devour the smaller (mātsya-nyāya or the law of the fish). The standard word for punishment in Sanskrit treatises was daṇḍa, meaning the staff or rod used to inflict blows, which symbolized the king's legitimate use of force, without which the world could not function. Indeed, the Arthasastra uses the term ‘administration of the staff’ (daṇḍa-nītī) as a synonym for government, since the staff represented ‘the theoretically constructive use of violence in service of upholding justice, preserving public order, and empowering the king’.Footnote 88 However, the king's punishment was supposed to be applied without passion, anger, or contempt; if punishment was not administered properly, it would wreak havoc on the kingdom.Footnote 89 In its depiction of royal rage preceding punishment, Dalpat Vilas therefore departs from the conventional stance in Sanskrit tradition.

The emperor Akbar who figures in the hunting episode of Dalpat Vilas is also far from the ideal ruler found in the Persian ethical literature (akhlāq) and ‘mirror of princes’ genre meant to advise rulers on proper behaviour. Persianate thought did not advocate the elimination of all emotions, unlike the injunctions against desire and anger in Indic tradition, but it sought foremost for balance. This is the message of the highly regarded work on ethics Akhlaq-i Nasiri; written in Persian in the thirteenth century, it circulated widely and was prescribed reading for Akbar's officials.Footnote 90 In the first section of the text, covering virtues and vices, its author Nasir al-Din al-Tusi declares: ‘Anger is tyranny and a departure from equilibrium in the direction of excess.’Footnote 91 He goes on to denounce angry men because they ‘constantly torment’ their friends, family, servants, and womenfolk ‘with the scourge of punishment, neither overlooking their stumbles, nor having compassion on their helplessness, nor accepting (the fact of) their being without fault’.Footnote 92 A similar exhortation for equilibrium in one's emotional state is found in Mau'izah-i Jahangiri, a Persian ‘mirror of princes’ composed at the court of Akbar's successor, Jahangir. While ‘opportune anger’ is said to be better for rulers than too much forbearance, the author also declares that the ‘ruler who is illuminated by the light of intellect, adorned by the ornament of wisdom, and distinguished by Eternal bounty attempts to extinguish flames of rage’.Footnote 93

Scholarship on the moral implications of royal anger in medieval Europe suggests there was considerable variation in thought, particularly depending on the time period. While the anger of kings was regarded as a sin and a sign of deficient moral stature in much of early medieval European literature, dominated as it was by clerical sensibilities, the concept of the just anger of kings was evoked by some authors in the twelfth century, and could be linked to the righteous anger of God.Footnote 94 Even within the same time period, however, a range of attitudes can be detected. As Barbara H. Rosenwein observes, ‘an entire repertory of conflicting norms persisted side-by-side throughout the Middle Ages. Some condemned anger outright; others sought to temper it; still others justified it’.Footnote 95 Whether it was approved of or not, however, anger was an emotion that was closely linked to kings and lords in medieval Europe, just as in Dalpat Vilas. Rather than indicating a reprehensible loss of control, some scholars argue that royal rage was deployed deliberately in medieval Europe, for political purposes and for public consumption, with established conventions.Footnote 96 Regarding royal rage, Gerd Althoff asserts: ‘Communication in medieval public life was decisively determined by demonstrative acts and behaviors … Many of the mannerisms of medieval communication, which may appear to us overemotionalized, were bound up with this demonstrative function—especially the demonstration of anger.’Footnote 97

Should we understand the anger of rulers in Dalpat Vilas, along the same lines, as a performance following a well-known social script, meant to legitimize the violence that followed? This vernacular chronicle consistently attributes the emotion of violent anger to the king and emperor, and to them alone, in a departure from the norms of Sanskrit literature in which anger was linked more to warriors than to their lords. For the author of Dalpat Vilas, royal rage was a familiar phenomenon associated with those wielding the highest political power, which caused fear in their subordinates. Yet this anger could have unpredictable and alarming consequences, as the next section of Dalpat Vilas's account demonstrates. If royal rage was indeed a performance, its message was by no means reassuring to the chronicle's Rajput audience.

Accounting for Akbar's aberrant actions

When we paused in our narration of the chronicle's plot some pages ago, Akbar had just sent the Kachwaha lord Man Singh to check on the injured Rajput, who soon died. Upon Man Singh's return to Akbar's tent to report this fact, he found the emperor raving (bakai chai), as if he had become another man. Akbar proceeded to say and do a series of things that made little sense. First, his utterances concerned food:

‘There's a cow; you Hindus should eat it. And you Muslims should eat a pig. If neither of you would customarily eat a ram, then throw the ram in a pot and cook it. If the ram should become a pig, then the Hindus and Muslims should get together and eat it. If it becomes a cow, the Hindus and Muslims should get together and eat it. If it becomes a pig, then the Muslims should eat it; if it becomes a cow, then the Hindus should eat it. Why, that will be a divine mix’! He was raving like this and began to rave about other things too.Footnote 98

Then Akbar turned his attention to his own appearance:

Removing his turban, the Emperor summoned barbers and said, ‘Cut my hair’. When he spoke like this, it made all the barbers run away. Then, he pulled a dagger out and began to chop at his hair himself. Then Sah Phatlah grabbed the Emperor's hands. Jain Khan and Sekh Pharid grabbed the dagger from the Emperor's hands. Then Sah Phatlah said, ‘if the Emperor's hair has to be cut, then it should get cut [by someone else]’. He said to all the nobles (umrāv), ‘Get the turbans off your heads’. Then they all removed their turbans. Removing them, the Hindus and Muslims tucked the turbans under their arms. Man Singh also took his off and tucked it under his arm. The Emperor had his hair cut.Footnote 99

After this, the emperor looked at the Hindu lords and started praising some lineages while denigrating others. Eventually, half the night having passed in this bizarre manner, one of the older Muslim nobles gently led Akbar to his tent. In the morning, the Hindu lords did their prayers and prepared themselves for the worst, in case death was in store. But nothing threatening occurred the next day; instead, the emperor had his beard shaved, tore his turban into fragments, and then distributed the pieces to the various lords, saying that he would ask for them back in the future when they mounted an assault on a foreign land (firaṅg). He was even pleased (rajū huyā) by a short, whimsical conversation he had with the young Dalpat about the imaginary future campaign. At this point, Akbar decided to call an end to the hunt and ordered the release of the many animals confined within the enclosure. He then secluded himself for five days within his own quarters, before finally leaving the temporary encampment.Footnote 100

The chronicler makes it clear that Akbar's nobles were apprehensive, not knowing what to make of the emperor's unexpected behaviour; it was so peculiar that all the Hindu lords got prepared to die. Fearing possible danger to Dalpat, the young heir to the Bikaner throne, the influential Rajput lord Man Singh Kachwaha even tried to send him away from the camp during the night, for safety's sake. The sense that things were out of kilter, that Akbar had somehow lost his balance, is conveyed in the chronicle's reports on Akbar's inversions of normal conduct—his shouting that Hindus should eat beef and Muslims pork, his cutting of his hair, and his release of the animals that had been rounded up with so much effort for the hunt. Akbar was transgressing conventional social boundaries by calling on Hindus and Muslims to eat food that was prohibited by their religions, by adopting a more austere style of hair, and by turning the captive animal prey loose. This was so far beyond the pale that the poet abandoned his use of the verb ‘to be angry’ (khijaṇau/khījaṇau) and replaced it with the word ‘to rave, babble’ (bakaṇau), when describing Akbar's emotional condition after the Rajput stabbed himself. The emperor had gone beyond the normal realm of anger into some other, extraordinary, state. From Dalpat Vilas's point of view, Akbar experienced a type of madness or mental disorder. A prolonged period of royal rage had deranged the emperor and transformed him into something different (aur rūp huyā).

Dalpat Vilas's interpretation of Akbar's experience during the hunt—first rage, then remorse, and finally raving—is not shared by the official history of Akbar's reign, the Akbarnama. In the respectful gaze of its author Abu'l Fazl, what Akbar underwent was a mystical vision rather than an emotional collapse. While Abu'l Fazl's Akbarnama and Dalpat Vilas agree that something out of the ordinary happened to the emperor, leading him to set free the animals that had been rounded up for the hunt, Akbarnama presents the incident in these highly positive terms:

In this wilderness the seeker for the truth stepped into the wilderness of search, adorning the fray of battle with himself in the park of prey-taking and giving splendid isolation to the private chamber of worship. Since he who seeks finds, the lamp of insight was lit, and the emperor was seized with a great joy. The tug of divine cognition cast a ray. Superficial persons of limited capacity would not be able to comprehend it if it were spoken, and not every wise person of enlightened mind could understand it … How could those who quaff wine at the banquet of the imperial presence know, without downing a distillation of that wine, what ecstasy is or of what insight consists? …

Some sharp minds who are granted audience believe that the workers of creation have placed world-adorning beauty in the splendour of his insight and that in his heart, which is intimate with the secrets of holiness, he speaks the language of heaven. Other courtiers think that he met a hermit in that wilderness and attained his desire … Some farsighted intimates think the animals of that plain divulged divine mysteries to him either in an unspoken tongue or in some common tongue. In any case, for a long time he who penetrates into the reality of unity was drowned in the lights of divine manifestation.Footnote 101

In these statements, Abu'l Fazl suggests that what befell Akbar was hard to describe and could not be readily understood by others. It is presented as some sort of spiritual experience involving a feeling of joy and closeness to God, not remotely related to anger.

Abu'l Fazl's emphasis on the religious dimensions of Akbar's anomalous behaviour at this hunt is part of his larger effort to portray the emperor as a superior man and semi-divine leader.Footnote 102 This was not the first mystical vision reported for the emperor in Akbarnama, which also mentions an earlier incident in January 1571. As proof of the divine favour shown to Akbar, Abu'l Fazl narrates that he once got separated from his retinue when hunting in the desert, grew so thirsty that he lost the ability to speak, and went into a trance. Fortunately, on that occasion, ‘the guides of the divine court led the water carriers through the trackless desert’ and the emperor was successfully rescued.Footnote 103 Experiences like these are presented in Akbarnama as manifestations of Akbar's saintliness and spiritual authority for, as Azfar Moin reminds us, ‘madness was a socially recognized station on the way to sainthood’.Footnote 104 The figure of the ‘holy fool’ (majdhūb), possessed by divine madness and indifferent to everyday cares, was well known in the Islamic world.Footnote 105 In his role as sacred sovereign, it was acknowledged that Akbar might behave in ways that deviated from the actions of regular men, precisely because he had greater spiritual insight.

Along the same lines of construing Akbar's conduct as divinely inspired, Abu'l Fazl casts the emperor's surprising decision to free the captive animals not as aberrant behaviour but as an act of gratitude for the religious blessing he had received. According to Akbarnama:

When the workers in the secret workshop of divine will let him down from the world of souls so that he could give order to the physical world, in gratitude for this great gift, an order was given for the salvation of several thousand animals, and fleet-footed, nimble heralds ran off in all directions to keep anyone from harming any of the animals and to let them go.Footnote 106

The abrupt termination of the hunt thus becomes a celebration of the emperor's special relationship with the divine in Abu'l Fazl's formulation.Footnote 107 The first illustrated manuscript of Akbarnama, presented to the emperor himself, highlights the unusual outcome of the hunt (Figure 3).Footnote 108 Akbar is shown in the process of calling off the hunt, while courtiers look on with perplexed expressions in the foreground. Some of the antelopes and deer that had been rounded up are visible in the upper left-hand corner, while the beaters who had accomplished that work appear to the emperor's right. In front of Akbar is a dead or injured animal, while to his side a young retainer holds a large sword that is bundled up in cloth and clearly not to be used. The spiritual implications of the episode are underscored by the seating of Akbar in an ascetic pose on a mat, with a downward gaze; he is depicted similarly, with his head facing down and his legs crossed, in the Akbarnama painting of his mystical interlude after getting lost while hunting in 1571.Footnote 109

Figure 3. Akbar releasing captive animals, 1578. Source: British Library Board J.8,4.

Akbar's releasing of the captive animals in 1578 was an act that would have held much symbolic resonance for the non-Muslim population of his empire. Akbar's decision to forego hunting on this occasion was in line with the stress in Jainism and other Indian religions on ahiṃsā, or non-violence, especially in reference to the killing of animals. The corollary to ahiṃsā was a vegetarian diet, which Jains and some Hindus followed, although not the martial Rajputs. Since Akbar had begun observing occasional meatless days shortly before the 1578 hunt, he may already have felt some sympathy for the notion of ahiṃsā, although an aversion to meat-eating was not unknown among Sufi ascetics either.Footnote 110 Indeed, M. Athar Ali has pointed out that Akbar visited several Sufi shrines while moving around the countryside for several months before arriving at Bhera in May 1578, and suggested that the emperor's Sufi leanings may have led to a distaste for killing animals at the hunt.Footnote 111 From Hindu or Jain perspectives, the freeing of his animal prey could be construed as a kind of penance on Akbar's part for the unnecessary violence he had inflicted on the Rajputs—a counter move that would ameliorate the harm he had causedFootnote 112—rather than as a merciful act of gratitude as Abu'l Fazl framed it in consonance with the Judeo–Christian–Islamic perspective. In any case, Akbar remained fond of hunting and never gave it up entirely, although the size of his hunts became more modest in later years.Footnote 113

That Akbarnama should diverge from Dalpat Vilas in presenting Akbar's experience at the hunt in such positive terms comes as no surprise. Because Akbarnama is fundamentally a text that aims to propagate the emperor's greatness, it consistently casts Akbar in the best possible light. According to the conventions of Persianate statecraft, just as in the Sanskrit case, anger was inappropriate for a ruler, who should ideally be judicious in his speech and actions. This was stated in no uncertain terms in the famous eleventh-century Persian treatise on governance, Siyasatnama (Book of Government): ‘It is the perfection of wisdom for a man not to become angry at all; but if he does, his intelligence should prevail over his wrath, not his wrath over his intelligence.’ Thus the bravest of heroes was the man ‘who can control himself in times of anger and does no action which he will regret afterwards when he has calmed down and regret is of no avail’—advice that Akbar might have been well off in heeding, if we give credence to Dalpat Vilas.Footnote 114 Mau'izah-i Jahangiri, composed in India in 1612, similarly condemns anger and warns the ruler of four things that ‘could bring calamity to the country and danger to the empire’, one of which was ‘harshness, that is, excessive expression of anger and immoderation in punishment and discipline … Thus rulers should not censure and reproach retainers on minor faults’.Footnote 115 The kind of behaviour described in Dalpat Vilas would hardly have commended Akbar to a courtly audience in the Persianate world, or among those who participated in the Sanskrit cosmopolis.Footnote 116 Hence, the absence of any allusion to anger in Akbarnama's narrative is not sufficient grounds for questioning Dalpat Vilas's account of what happened on that day in May 1578; in this respect, it is more useful as a guide to Abu'l Fazl's conception of a perfect ruler.

Other Indo-Persian chronicles offer a less idyllic view of the 1578 hunt. Particularly important is the brief description in Tarikh-i Akbari, whose author Arif was in the employ of a high-ranking Mughal noble.Footnote 117 While Arif agrees with Abu'l Fazl in interpreting Akbar's experience as ‘a mysterious Divine Call’, he also corroborates the Rajasthani chronicle's claim that a Rajput subordinate was punished and died in the following words: ‘During the same time, the emperor ordered that one of the Rajputs who had committed a sin be flogged. After receiving two or three lashes, he lost all power to receive any more. He was a compound of ignorance, so he thrust dagger [sic] into his stomach and died.’Footnote 118

Tarikh-i Akbari agrees quite closely with Dalpat Vilas in the details regarding the Rajput, who was whipped for some offence, stabbed himself in the stomach, and died. But—and this is a big but—Arif does not connect the dying of the Rajput with the termination of the hunt in any way; indeed, his short report on the unusual hunt occurs before he brings up the Rajput, as if the two events were entirely unrelated. Yet, considering the brevity of Arif's overall account of this episode, which notes the cutting of Akbar's hair but not the release of the captive animals, it is striking that he bothered to discuss the Rajput's self-inflicted wound at all. That he did so suggests that the flogging and death did in fact take place, and that something about the incident made it unusual enough to merit mention.

Abdul Qadir Badauni, a malcontent scholar who was highly critical of Akbar's religious experimentation, offers yet another version of events. Like Abu'l Fazl and Arif, Badauni reports a sudden transformation in Akbar that had no apparent external cause—there was no dying Rajput and no imperial anger involved in this surprising event. In Badauni's words:

Suddenly all at once a strange state and strong frenzy came upon the Emperor, and an extraordinary change was manifested in his manner, to such an extent as cannot be accounted for. And everyone attributed it to some cause or other; but God alone knoweth secrets. And at that time he ordered the hunting to be abandoned.Footnote 119

While ‘strange state’ and ‘strong frenzy’ are not equivalent to violent rage, this description of Akbar's condition implies an agitation of his mind and body that was intense and bizarre. It meshes better with Dalpat Vilas's account than does Akbarnama's claim that the emperor had an uplifting mystical experience. Badauni also reports on the haircutting by Akbar and most of his companions; he adds the news that Akbar distributed gold at the site and ordered a building and garden to be built there. Perhaps most intriguing is Badauni's final comment on the incident: ‘And when news of this became spread abroad in the Eastern part of India, strange rumours and wonderful lies became current in the mouths of the common people, and some insurrections took place among the ryots (peasants), but these were quickly quelled.’Footnote 120

Badauni's statement indicates that Akbar's actions were closely observed and widely reported, and that his erratic behaviour on the occasion of this hunt was a source of speculation and unrest among the peasantry.

Yet another chronicler from Akbar's reign, Nizam al-Din Ahmad, covered the 1578 hunt in an affirmation of its startling and sensational nature. His Persian history, Tabaqat-i Akbari, follows Abu'l Fazl's general thrust in depicting Akbar's experience as ecstatic and ineffable; it agrees with Badauni that the emperor gave away gold as alms, called for the construction of a building and garden at that site, and ordered that ‘the game that had been collected should be allowed to escape’.Footnote 121 Like all the other texts I have just covered—Dalpat Vilas, Abu'l Fazl's Akbarnama, Arif's Tarikh-i Akbari, and Badauni's Muntakhab al-Tavarikh—this work also refers to the cutting of hair by Akbar and many of his companions. And, as in all the accounts except for the shortest one (Arif's Tarikh-i Akbari), Nizam al-Din Ahmad's Tabaqat-i Akbari specifies that the captive animals were set free. Both Akbar's altered condition and the releasing of the entrapped animals were dramatic events, and understandably worth noting in a chronicle of his reign. Akbar's haircutting is another matter. This highly visible change in his bodily appearance was perhaps seen as a testament to the magnitude of what Akbar had undergone. It was a deviation from his regular practice, in that Akbar had years earlier adopted the Indian custom of allowing his hair to grow long rather than keeping it short in the Persianate manner.Footnote 122 Thus, the Persian-language authors may have construed both the haircutting and the freeing of the animals as inversions of the normal order that signified the emperor's state of divine madness.

Of the several Persian chroniclers, Badauni and Arif correspond most closely to Dalpat Vilas and its allegation about Akbar's anger, even if they do not describe it explicitly. Arif refers to an incident of flogging after which a Rajput stabbed himself and died, just as in Dalpat Vilas, although he does not associate that with Akbar's unusual mental condition. If we believe the Rajasthani chronicle, Akbar got so worked up with anger, and perhaps also guilt about the Rajput's death, that he went over the edge; his releasing of the entrapped animals at the hunt can then be construed as an act of atonement for how he had treated his Rajput underlings. Rather than reflecting a kind of divinely granted mystical vision, as Abu Fazl states, the ‘strange state and strong frenzy’ that Badauni describes may have actually been a consequence of the emperor's remorse at his victim's needless death. But my main purpose in this article is not to establish the truth of what happened at the hunt of 1578. Dalpat Vilas's account of the episode, which lacks any supernatural or spiritual element, may be more plausible to us today than that of Abu'l Fazl. The salient point, however, is that several commentators understood Akbar to have undergone something abnormal, even if they differed on whether the experience was positive or negative.Footnote 123 Whatever Akbar may have experienced, it was not an ordinary or easily comprehensible matter, for observers were clearly alarmed and unsettled by it.

Different perspectives/different emotional communities?

A close reading of these five accounts of the 1578 hunt has revealed several points of convergence between them—Akbar's temporary but intense transformation, the shortening of his hair, and the suspension of the hunt. Conspicuously missing in the Persian histories is any reference to anger—the emotion that is so critical to the Dalpat Vilas narrative. In this final section of the article, let us reflect on the reasons why the hunt episode in this Rajasthani chronicle was at such odds with the other versions of the same event. How much do these differences have to do with the authors’ relative proximity to the imperial centre or the nature of their audience? Or are there other factors involved that inclined the authors to perceive not only the emperor, but also the emotional atmosphere at the hunt in dissimilar ways?

One possibility is that Akbar's anger was intentionally omitted by the Persian historians, so as to avoid any hint of a flaw in the emperor's conduct. The compulsion to praise Akbar would have been especially strong for his close confidante Abu'l Fazl, as well as Nizam al-din Ahmad, who served as head of the military department (mīr bakshī), one of the most important administrative positions in the empire. Badauni, on the other hand, had an animus toward Akbar, whom he viewed as deviant in religion; Badauni's history had to be written in secret since he was in the emperor's employ as a scholar and translator. As one might expect, his allusion to Akbar's ‘strange state and strong frenzy’ at the hunt leading to rumours among the populace is the most damaging comment made. The fourth chronicler, Arif, did not move in quite as high circles as Abu'l Fazl, Nizam al-din Ahmad, and Badauni, who were frequently present at the imperial court,Footnote 124 but his patron and past vizier (chief minister) Muhammad Khan did.Footnote 125 As members of Mughal courtly society, these authors must have been highly aware of the consequences of besmirching the emperor's character.

The unknown author of Dalpat Vilas in contrast would have had little reason to fear imperial opprobrium. Writing in a vernacular language for a local audience rather than in Persian, the cosmopolitan language of empire, there was little chance that the emperor or his courtiers would ever encounter his chronicle. He had only to satisfy the sensibilities of local warriors, starting with the patron and hero of his text, the Rathor-clan warrior Dalpat. In 1600, the estimated date of Dalpat Vilas's composition, Dalpat Singh held an imperial rank (manṣab) of 500, the lowest-ranking among the nobility (umarā) during Akbar's reign, and was still under the shadow of his father Raja Ray Singh, the king of Bikaner. Around that time, Dalpat had attempted to forcibly seize territory from his father, compelling Ray Singh to leave the imperial court and return to Bikaner to deal with the situation.Footnote 126 Dalpat's rebellion soured his relationship with his royal father even more than with the emperor; it may have also inspired the commissioning of a chronicle about him, as part of an effort to establish an independent, heroic identity. Dalpat's troubled relationships with his superiors may explain why his chronicler had no qualms about casting both Raja Ray Singh and emperor Akbar as angry and violent rulers. Doing so would have made Dalpat a more sympathetic character, in a literary strategy that may have been pursued throughout the entire text, whose only copy unfortunately ends shortly after the qamargha incident. Highlighting the anger of the rulers whom Dalpat was rebelling against would have suited the propaganda purposes of his chronicler, just as eliding any mention of Akbar's anger would serve the goals of the imperial historian-courtiers.

But what if the presence or absence of anger in these accounts was not so deliberate or instrumental in its intentions? Another possibility is that the authors of the Persian texts or their informants did not perceive Akbar's anger or did not register it as significant. Akbar might not have been angry, from their perspective; alternatively, his anger was so slight and so inconsequential that it did not merit mention. It is likely that Akbar did command the flogging of a Rajput, who subsequently stabbed himself and died, given that the episode appears in both Dalpat Vilas and Arif's Tarikh-i Akbar. Arif suggests the violence was justified since the Rajput ‘had committed a sin’, and that he killed himself because he could not endure any more flogging. This suicide was odd enough to be noted in brief by Arif, who completed his history less than two years after the events described. However, there is no indication that Arif understood the emperor to have been angry when he issued his order for corporal punishment, nor that Arif drew any connection between this incident and the cessation of the hunt.

This explanation for the divergences in our texts is made more plausible if we accept Barbara H. Rosenwein's notion of emotional communities. She defines an emotional community as ‘a group in which people have a common stake, interests, values, and goals. Thus, it is often a social community. But it is also possibly a “textual community”, created and reinforced by ideologies, teachings, and common presuppositions’.Footnote 127

Rosenwein asserts ‘that there were (and are) are various “emotional communities” at any given time’ and that an individual could belong to more than one.Footnote 128 An emotional community shares not just one emotion but a whole set of them, in clusters that differentiate it from other communities. Some emotions might be shared by different emotional communities, suggesting that these communities might have some overlaps in their membership as well, in theory. In her own research on early medieval Europe, Rosenwein examines numerous texts of varied genres, ranging from funerary epitaphs, to letters, homilies, panegyrics, and more, and compares the sets of emotions that are expressed in these items. My inquiry is much more limited since I am primarily looking at a single emotion expressed in one text, and comparing it to several other texts where it is absent. One emotion is not sufficient to define a distinct emotional community, nor is one text adequate. However, the concept of emotional communities may be useful in understanding why chroniclers might differ in their perception of the presence of anger, as well as in their inclination to record it. That is, anger may have had a different significance for the emotional community in which Dalpat Vilas participated relative to the emotional community or communities of the authors of our Persian histories.

While little can be said in detail about their emotional concerns, the historians who wrote in Persian shared a common courtly culture that was disinclined to regard rulers as unjust in their anger.Footnote 129 Take the case of Lashkar Khan, who had held the important positions of imperial paymaster (mīr bakshī) and petition-receiver (mīr ‘arzī). In Abu'l Fazl's words: ‘In his foolishness he appeared at court drunk in broad daylight and started a quarrel. When the situation was reported to the emperor, he had him tied to a horse's tail, paraded around, and sent to prison to teach him and others a lesson.’Footnote 130

Akbar did not get angry with Lashkar Khan and only punished him for didactic purposes, according to Abu'l Fazl. The less polished Arif, a bit out of step again with the inner circle, attributes anger to the emperor in reference to Lashkar Khan but only mentions the less humiliating punishment of imprisonment.Footnote 131 A late eighteenth-century text, Maathir-ul-Umara, comments that ‘the excessive punishments imposed by the Emperor may seem to savour of wrath’ but goes on to reject the possibility that Akbar overreacted out of anger, stating that ‘the punishment was just’ in the case of Lashkar Khan, a ‘pomp-loving’ and mean-spirited man who deserved what he got.Footnote 132 In other hands, the emperor may have felt the emotion of anger, but only rightfully so and in a measure that was appropriate for the crime or sin, with no breach in propriety. While there were some discrepancies within the rarefied realm of Mughal-era Persian historiography, the expectation was that rulers would act dispassionately and justly in using their punitive power. This may have led observers to overlook the possibility or discount the importance of excessive royal anger, making such incidents invisible or irrelevant to these courtiers.