“Chicago—from its founding, a city of ethnic politics—has become a city of racial politics. Out of the melting pot, with its generations of immigrants, have come three shades of people—Black, white, and brown—who coexist but rarely mix.”Footnote 1 The February 1983 cover story of Chicago magazine spoke to the changing tides of race and politics in the Second City. At the time, Chicago was in the midst of an unprecedented mayoral election that promised to be the most serious challenge to the city's political machine in over half a century. The Regular Democratic Organization had long entrenched itself at the helm of City Hall using an expansive system of white ethnic patronage that exchanged jobs and services for votes and power. Chicagoans of color, however, found themselves largely excluded from this tightly managed political rewards system, which depressed their electoral engagement and maintained economic inequality in a heavily segregated urban landscape.

Unlike any other electoral contest before it, the 1983 Chicago mayoral election polarized the city along racial lines. On the one hand, a dramatic political mobilization of Black neighborhoods, boasting tens of thousands of newly registered Black voters, rallied behind the candidacy of U.S. Representative Harold Washington and his anti-machine movement. On the other, the Democratic Machine's white ethnic power-elite channeled their financial and political resources completely against the Black candidate in the primary, and ultimately defected from their party in the general election to support white Republican Bernard Epton. Indeed, the City of Chicago was transformed into a city of racial politics in 1983.Footnote 2 Yet this well-known story in the annals of urban political history leaves much to be discovered about the third “shade” mentioned in the Chicago magazine article. Who were the “brown” Chicagoans, did they even identify as such, and how would they vote?

A series of scholarly works on the role of Latinos in the 1983 election assertively attributes Harold Washington's mayoral victory, in part, to the grassroots mobilization of a nascent Latino voting bloc that embraced a non-white minority identity.Footnote 3 In this article, I make two arguments that complicate the conventional narrative and its presumption of Latino political and racial consciousness. First, the election pushed Chicago's Latino population to grapple significantly with their relationship to whiteness, a process that exposed deep racial divides among Latino ethnic subgroups, and by extension between Latinos and Blacks. Despite these rifts, Washington's campaign successfully advanced the institutionalization of a panethnic Latino category in mainstream political discourse. Together, these arguments contend that the “Latino vote” in 1983 was neither a racial nor political monolith, but rather an imagined constituency fashioned from the top-down by the campaign and Latino political elites. Drawing from campaign records, electoral data, and bilingual media coverage, I offer a re-evaluation of the 1983 election—as well as the first detailed analysis of Latino outreach during the primary campaign—that reveals a foundation of discord in the famed “rainbow coalition.”

The 1983 election was a critical inflection point for the political and racial self-fashioning of Chicago's Latino population, which also had to adapt to the shift from ethnic bloc politics to racial politics. As recent work by historian Mike Amezcua demonstrates, Latino Chicago's limited relationship to the Democratic Machine during the 1960s and 1970s was defined by a national-origin, ethnic-politics approach characteristic of white immigrant groups in which “[Mayor Richard J.] Daley and his Amigos created a mutually beneficial relationship rooted in political favors and symbolic gestures of exchange.”Footnote 4 Mexican American political and business elites of the Daley era helped maintain the dominance of the white-controlled machine and quelled the impact of growing racial-cultural nationalism. This holding pattern, however, could not last long given the rise of radical social movements led by young Puerto Rican and Mexican activists, increasing voter registration, and a simmering resentment among Latinos over the diminishing returns of ethnic machine patronage.

But a race-based Latino political consciousness was not universally accepted, nor did it easily transfer into formal electoral politics. Lilia Fernández points to a dramatic transition of Latino racial self-identification evidenced by the 1980 U.S. Census. “Many had concluded that ‘white’ was not the racial identity they had been assigned in the local social order,” Fernández argues, “nor one they wished to claim.”Footnote 5 Equally telling, however, is that 45 percent of Chicago's “Spanish origin” population still considered themselves racially white.Footnote 6 Latino racial identity in the 1980s was very much in flux, and a pervasive rhetoric of racial resource competition and a supposed Black takeover of City Hall heavily influenced Latino political decision making. This election bore witness to the intense growing pains of Latino racial consciousness and the Washington campaign's effort to inoculate Latinos against a potent strain of anti-Black racism. As such, Latino support for, and opposition against, Harold Washington laid bare intra-ethnic divisions between and within Latino subgroups, stratified by their distinct racial self-positioning at the ballot box.

Harold Washington's campaign for mayor not only urged Mexicans and Puerto Ricans to view themselves as non-white racial minorities, but also actively categorized them as a unified ethnic group. It was clear to Washington and his allies that appealing to a panethnic Latino constituency was the most efficient way to mobilize the ethnically heterogeneous and geographically fragmented Latino neighborhoods. Archival evidence from the campaign's Latino Operations Department reveals the intentional use of bold, panethnic rhetoric and symbolism that prompted voters to reorient their identities beyond their national origins and toward a panethnic Latino label (Figure 1). The Washington campaign courted this broad constituency by flying in national Latino leaders for endorsements and investing in Spanish-language advertising that explicitly spoke to the “Latino” voter. I argue that this strategy brought the panethnic political rhetoric characteristic of presidential elections to the local level and helps merge the local and national scales together in the historiography of the “Latino vote.”Footnote 7

Figure 1. The Washington campaign's Sale El Sol slogan covered Latino neighborhoods leading up to the general election. “The Sun Rises for the Latino with Washington,” the poster claimed, promising new opportunity and inclusion in City Hall for those diverse communities that the campaign unitarily labeled as the “Latino” constituency. Copyright © Marc PoKempner, “Image of Harold Washington campaign photos in Spanish on car,” photograph, 1983, in Harold! Photographs from the Harold Washington Years (Evanston, IL, 2007), 116. Used with permission of Northwestern University Press.

More generally, Washington's candidacy fundamentally accelerated the development and legitimation of “Latino” as a mainstream social category. Early works on Latino panethnicity, such as Felix Padilla's foundational 1985 study, Latino Ethnic Consciousness, emphasized the social pressures and cultural similarities that led Latin American immigrants and their U.S.-born descendants to adopt a common identity across nationalities. However, my research findings align more closely with the work of Arlene Dávila and Cristina Mora, who argue that a combination of external actors, including the nation-state, business, media, activists, and bureaucrats, played a more central role in the institutionalization and imposition of the panethnic labels “Latino” and “Hispanic.”Footnote 8 I add to this list political campaigns, like Washington's, that facilitated the discursive construction of a consolidated Latino constituency—joining the efforts of national entities such as the Congressional Hispanic Caucus. The Chicago story shows how a political campaign, the Latino political elites working within it, and corresponding media coverage contributed to the process of making Latinos a “legible” population in politics and beyond.Footnote 9

This project also helps bridge the divide between the literature on Black mayors and the political science research on Latino voters. A movement for Black political empowerment took hold of major urban hubs and led to Black mayoral victories starting in 1967.Footnote 10 The early 1980s brought Latino mayors into the fold with the elections of Henry Cisneros in San Antonio and Federico Peña in Denver joining those of Harold Washington in Chicago and Wilson Goode in Philadelphia. But while the ascendancy of Black and Latino politicians was historically concurrent, studies on Black and Latino candidates do not generally intersect. In a context where studies on Black candidates emphasize the mobilization of Black voters, and studies on Latino candidates emphasize Latino mobilization, my approach to the election of Harold Washington uniquely highlights the reaction of Latino voters to a Black candidate.Footnote 11 Thus when compared to Cisneros and Peña's near unanimous Mexican support, we can see how the “complexity of Latino racial identity” in Chicago, paired with negative reactions to Washington's Blackness, challenged the perceived inevitability of Latino voting blocs at the time.Footnote 12

Chicago's status as the largest majority-minority city in the nation elevated the 1983 election to a highly publicized test for Latinos’ role in urban society. In the context of postwar deindustrialization, white flight, and segregation, recent works on Latino urbanism have established the unique vacancies filled by Latinos in commerce, art, culture, labor, racial hierarchies, geographic space, built environment, activism, and, in this case, formal electoral politics. My focus on the election reveals Latinos’ indelible role in reshaping urban political regimes, or, as Llana Barber frames it, how Latinos “struggled not just within the city but for the city.”Footnote 13 Political activist Rudy Lozano was one such leader in the struggle for the city, whose life will serve as our guide through Latino Chicago's history of community organizing, the rise of independent politics, Washington's campaign, and finally the issue of historical memory in his death. As Latino Chicagoans struggled to define their political relationship to whiteness and to each other, Harold Washington's campaign for mayor prompted them to ask: “¿Qué somos? What are we?”Footnote 14

Like most Mexican American youth coming of age in Chicago during the 1960s, Rudy Lozano attended underfunded public schools and walked on neglected streets in a city divided by race. In the early 1970s, Lozano drew inspiration from his working-class upbringing as he found his calling in community organizing. One of his earliest experiences in the field came during college at the University of Illinois at Chicago, where he organized protests to increase student diversity and the number of Latino faculty. By 1979, Lozano had fully embraced organizing as his profession, evidenced in his role as the Midwest Organizing Director of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU), through which he made major gains in the unionization of underpaid Mexican American tortilla factory workers.Footnote 15 By no means a path breaker in this regard, the young Lozano followed in the tradition of pan-Latino labor and community organizing in Chicago during the post–World War II era.

Causes such as school improvement and fighting urban renewal fueled the creation of civic groups such as Casa Aztlán, the Puerto Rican Cultural Center, El Centro de la Causa, and the Young Lords Organization. And while most groups catered to a specific national origin, Mexicans and Puerto Ricans began to unite around common causes starting in the late 1960s. Of all the pressing issues, however, fair access to employment opportunities became the predominant concern for Chicagoans of Latin American descent during the 1970s. Economic restructuring in that decade transitioned Chicago's workforce toward the service economy and white-collar jobs, but the majority of Latinos found themselves left behind in dying industries like manufacturing that “reinforced the role of Latinos in the Chicago economy as low-wage, dominated workers.”Footnote 16 A shared experience of discrimination and underemployment across Latino ethnic subgroups thus ushered in a new model of panethnic organizing spearheaded by the Spanish Coalition for Jobs (SCJ), identified by Felix Padilla as “Chicago's first Latino protest organization … comprised of more than one Spanish-speaking group.”Footnote 17

Established in 1971, the Spanish Coalition for Jobs was a collective of twenty-three community organizations from both Mexican and Puerto Rican neighborhoods across the city that pushed for affirmative action in hiring. SCJ targeted the powerful Illinois Bell Telephone Company in its first major campaign, which, after months of picketing and tense negotiations, resulted in hundreds of jobs for Latino workers and new training initiatives. A year later, SCJ enjoyed similar success in its campaign against the Jewel Tea Company.Footnote 18 Other panethnic labor coalitions, such as Asociación pro Derechos Obreros (Association for Workers’ Rights) and the Latin American Task Force, soon followed the momentum set by SCJ and pushed for affirmative action not only in the private sector, but also in public entities such as the Chicago Transit Authority and other city employers.Footnote 19 Despite these gains, low union membership and the dispensability of undocumented workers prompted these groups to realize that tangible gains for Latino workers also called for a wholesale transformation of the city's political order.Footnote 20

Latino labor activism helped set the stage for the independent political movement of the 1980s that fixed its eyes on dismantling the Machine's patronage system. The City of Chicago employed tens of thousands of people, but “jobs and economic favors were differentially and disproportionately allocated, based upon voting strength.”Footnote 21 In addition to thousands of patronage jobs or “temporary appointments” at the disposal of the mayor, the Machine also held sway over trade unions and the private sector through government contracts, licensing, and setting the prevailing wage in select industries.Footnote 22 Though some groups such as the Mexican American Democratic Organization (MADO) sought to bring Machine spoils to their communities, decades of continued economic stagnation proved to many that collaboration with Mayor Richard J. Daley and his successors only produced symbolic gestures and a handful of token appointments.Footnote 23 In this context, some community activists, including Rudy Lozano, shifted their efforts from strikes and protests to the political realm in order to advance the material wellbeing of the Latino community.

Lozano co-founded the Independent Political Organization (IPO) of the Twenty-Second Ward in 1981, one of many IPOs across Chicago part of a broader independent political movement in Black and Latino wards. Though these organizations worked almost exclusively at the local level on ward-specific campaigns, the independent movement found its first major Black–Latino partnership in the contest for the 1982 Illinois legislature. Officially launched in January of that year, the “Black-Latino Alliance” assembled a multiracial slate of “people-oriented candidates” composed of Danny Davis, Jane Flagg, Arthur McBridge, Jose Salgado, Juan Solíz, Arthur Turner, and Carmelo Vargas—all of whom ran against Machine-backed incumbents.Footnote 24 Major Spanish-language newspaper El Heraldo de Chicago noted the significance of this challenge to the city's political machine that had “traditionally given its support to other ethnic groups at the expense of blacks and Latinos.”Footnote 25 But what some observers considered “an important test of political strength for Latinos in Chicago” ended with Machine victories and no new Latino representation in the statehouse.Footnote 26

Regardless of the Black–Latino Alliance's disappointing electoral returns, their candidacies created strong momentum for the independent movement leading up to the 1983 city elections. In late 1982, Rudy Lozano officially threw his hat in the ring and entered the world of electoral politics as a candidate for alderman of the Twenty-Second Ward, one of fifty city council districts. The Twenty-Second Ward was home to the Mexican enclave of Little Village and boasted the highest density of Latino residents in the entire city at 64 percent, as well as a substantial Black population at 21 percent.Footnote 27 Despite its majority-minority composition, a white politician named Frank Stemberk represented the ward in City Hall and was fiercely loyal to the Regular Democratic Organization. Mexican American residents considered the alderman completely out of touch with their community and came to know him as the “absentee alderman,” a title that proved to be quite literal when he was eventually investigated by the Cook County State's Attorney for living in the suburbs rather than within city limits (let alone the ward he represented).Footnote 28

Lozano's campaign reflected the growing desire for self-governance among Latino Chicagoans and was closely aligned with the independent movement's mayoral contender, U.S. Representative Harold Washington. Washington was a reform candidate poised to become the city's first African American mayor. Originally, Washington hesitated to run again in 1983 due to a previously failed attempt and concerns over historically low Black voter turnout. An unprecedented surge in Black voter registration numbering in the tens of thousands, mobilized by Washington's barrier-breaking candidacy, however, rapidly assuaged his reservations.Footnote 29 With the full backing of the Black electorate, Washington pushed forward with an independent agenda that challenged the Machine's patronage system and promoted the equitable distribution of city jobs and services. Seeking to bring together a “rainbow coalition,” as well as unleashing the full potential of the independent political movement, Washington also extended the reach of his campaign through a series of partnerships that included endorsing Lozano's bid for alderman.

Washington faced two other candidates, Jane Byrne and Richard M. Daley, in the 1983 Democratic primary for mayor. Byrne, the first woman elected mayor of Chicago in 1979, was well supported in white working-class neighborhoods and benefited from her status as the incumbent. She struggled, however, in her relationship to impoverished African Americans living in the South Side who criticized her failure to address job decline and dilapidated public housing. By the eve of the election, she consistently found herself in hot water with Black and Latino activists on many issues including labor disputes, public housing, a failing school system, and the lack of non-white political appointees.Footnote 30 Cook County State's Attorney Richard M. Daley posed the most significant challenge to Byrne's re-election campaign among ethnic white voters, benefitting from his legacy as son of former Mayor Richard J. Daley who held office for twenty-one years. Together, Byrne and Daley confidently courted the majority of white voters in Chicago, most of whom were deeply invested in the maintenance of patronage that benefitted their neighborhoods.

Whereas white neighborhoods split between Byrne and Daley, and Black voters unanimously supported Washington, the allegiance of Latino voters was subject to wide-ranging speculation. Mainstream media outlets such as the Chicago Tribune pointed to a lack of centralized leadership as the source of Latino political disunity. The Tribune's 1982 cover story asked, “Who Speaks for Hispanic Americans?” Journalist Manuel Galvan described Chicago as “the one heavily Hispanic city that mirrors the special problem of Hispanics nationally—it does not have a Hispanic spokesman for its entire population. Instead, the various communities have their movers and shakers, who sometimes work together and sometimes fight.”Footnote 31 Indeed, Chicago's Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and Cubans had their own respective community leaders who rarely joined forces and complicated the creation of an intra-ethnic political bloc—a microcosm of the challenges facing the unity of the national Latino electorate at the time.

But in an election so focused on jobs and city resources, the 1983 mayoral primary revealed the centrality of anti-Black thinking in Latino political decision making, an issue that hampered Latino political unity far more than decentralized leadership. Harold Washington's candidacy exacerbated Latinos’ existing anxieties from earlier decades regarding unemployment and the unequal distribution of city services, though this time they feared that a Black mayor would make matters worse by favoring African Americans over Latinos in the allocation of resources and jobs. The Daley campaign embraced this anti-Black rhetoric early on to deter Latino support for Washington. Daley accepted the endorsement of a 250-member coalition of six Latino organizations in December 1982. The group's spokesperson, Lupe Perez, warned of the pro-Black favoritism that Washington would practice in office and labeled him “a civil rights candidate of the black community and not a political candidate to represent all the citizens of Chicago.”Footnote 32 Though the coalition also denounced Byrne for neglecting Latino community development, their critique of Washington was explicitly racial.

Mayor Jane Byrne also adopted the rhetoric of racial resource competition in her re-election campaign. A televised debate on February 7, 1983, on WBBS-TV's Spanish-language public affairs program Opinion Publica, put Byrne's strategy on full display. Latino representatives from the three Democratic mayoral campaigns addressed a variety of topics on behalf of their candidates, and affirmative action in city hiring raised the most controversy. Byrne's assistant press secretary for Spanish communication, Colombian-born Fernando Prieto, spoke on her behalf and emphasized the zero-sum game for Latinos under a Washington administration. “We can go to the Department of Human Services and we will see how that department is very dark,” Prieto said of the department's many Black employees, “can you imagine how it would be with a Black mayor?” Though some community leaders such as Puerto Rican minister Jorge Morales demanded an apology from Byrne for the “use of these racist tactics” that sought to pit Latinos against Blacks, Prieto's statement likely validated the fears of many Latinos hoping to earn a city job.Footnote 33

Though Congressman Harold Washington was aware of his opponents’ strategy to exaggerate the economic competition between Blacks and Latinos, he underestimated its influence on Latino voters during the primary. Washington operated under the assumption that Latinos already viewed themselves in racial terms on par with Blacks, and thus expected that his message of racial uplift for Black voters would naturally carry over to Latinos. This erroneous assumption was the Achilles heel in his failed run for mayor in the 1977 special election. Steve Askin, press secretary for the 1977 Washington mayoral campaign, outlined for Washington the lack of Latino support for his candidacy in a postmortem campaign analysis and warned, “it is often blithely assumed that Spanish-speaking voters will align themselves with blacks.”Footnote 34 Unfortunately, Washington's primary campaign failed to heed that lesson six years later, with an outreach to Latino voters incomparable to the massive grassroots mobilization that characterized his ground game in the Black South Side.

The perception that Washington collapsed the Latino experience into the Black agenda worsened his appeal. The viewpoint of Mexican American data-entry operator Marie Helen de la Cruz clearly illustrates the candidate's struggle to relate, as seen in her negative reaction to Washington saying that Latinos were also “niggers”—an attempt to equate Latino and Black oppression. Washington's comparison was not new to U.S. politics, reflecting a similar statement by Congressman Ronald V. Dellums: “If you're black, you're a nigger. If you're an amputee, you're a nigger. Blind people, women, students, the handicapped … are all niggers.”Footnote 35 Yet for voters like de la Cruz, that kind of rhetoric was both polarizing and offensive, suggesting that Washington viewed politics only in Black terms and would merely use Latinos to achieve his own community's goals. “It would be wrong for people to assume that Latinos will support Washington because he is black,” said de la Cruz, “… I don't see why there should be a natural coalition between blacks and Latinos.”Footnote 36

Of Washington's few Latino outreach events during the primary, only Tony Bonilla's visit to Chicago directly addressed Latinos’ concerns about electing a Black mayor.Footnote 37 Bonilla was president of the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), the oldest national Latino civil rights organization, established in 1929. Jesse Jackson's urban justice group, Operation PUSH, flew Bonilla in from Texas to a rally where the LULAC leader endorsed Washington's bid for mayor just weeks before the primary (Figure 2). Bonilla framed his endorsement as a challenge to anti-Black thinking in the Latino community and told the racially diverse crowd that he had received numerous calls asking why he was “working with the enemy—Blacks.” In response to this zero-sum game mindset, Bonilla asserted that “it is time for Blacks and Hispanics to stop fighting,” calling for unity between “tacos and biscuits.”Footnote 38 But this ringing endorsement from a national Latino figurehead did not boost local Latino support.

Figure 2. Tony Bonilla, Congressman Harold Washington, and Jesse Jackson at a rally convened by Jackson's organization Operation PUSH in January 1983. David Williams, photograph, Jan. 1983, folder 26, box 3, Pre-Mayoral Photograph Collection, Harold Washington Archives and Collections, Special Collections, Chicago Public Library, Chicago, IL. Used with permission of Chicago Defender.

On February 22, 1983, Harold Washington won the Chicago Democratic primary with 36.3 percent of the vote; Byrne arrived in second place with 33.6 percent, and Daley in third at 29.7 percent.Footnote 39 Washington won a narrow victory margin because of an unprecedented Black voter turnout and a white electorate split between Byrne and Daley. But when it came to Latino voters, Washington's performance was abysmal. The Midwest Voter Registration Education Project's primary election exit poll found that 51.4 percent of Latinos supported Byrne, 34.5 percent for Daley, and only 12.7 percent voted for Washington.Footnote 40 Washington failed to win any of the heavily Latino wards, such as the Seventh Ward in which Byrne and Daley carried the Mexican vote. Similarly in the Thirty-Second Ward, approximately half Latino, Byrne carried the Latino precincts and Daley the white neighborhoods.Footnote 41 The fact that unpopular incumbent Byrne received the majority of Latino votes—despite major political blunders on her part, including the removal of nearly all Latino appointees from the previous administration without replacement—spoke volumes to Latino distrust of the Black candidate.Footnote 42

Latinos’ historically varied racial formations and spatial positioning in relation to Blacks helps contextualize the salience of anti-Blackness among Latinos in the 1983 election. Over 420,000 Latinos called Chicago home in the 1980s, accounting for 14 percent of the city's population. Chicago also boasted the only substantial urban representation of the nation's three largest Latino subgroups—Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Cuban—an unparalleled demographic spread that laid bare the differences between Latino subgroups, especially in their relationship to whiteness (Table 1). How Latinos categorized themselves along the city's Black/white racial binary deeply shaped political proclivities to either join the Machine's ethnic white base or ascribe to a rights-based, minority identity. Defining one's racial identity, however, had proven a challenging and divisive exercise for all subgroups. One Latino Chicagoan summed it up for the Chicago Tribune in a 1974 man-on-the-street interview: “Blacks call us white, whites call us brown, and we have a helluva time deciding what we're going to call ourselves!”Footnote 43

Table 1. Latino population in Chicago by national origin, 1980

Source: U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, “Table 70: Total Persons and Spanish Origin Persons by Type of Spanish Origin, Race, and Sex, for Areas and Places: 1980,” in 1980 Census of Population, vol. 1, ch. B, pt. 1, (Washington, DC, 1983), 278.

Mexicans were the first Latinos to arrive in Chicago, with the pioneer wave settling in South Chicago during the 1910s. Historians such as Michael Innis-Jiménez have shown how this group developed a distinctly racialized Mexican identity, a product of discrimination in labor and society as well as their “selective resistance” to cultural assimilation. Nevertheless, Mexicans also benefitted from their distance to Blacks in employment and housing, occupying a liminal third space in Chicago's Black/white binary.Footnote 44 By the 1970s, the growth of both the Mexican and Black populations resulted in greater encounters and less geographic distance between the two groups, especially in the Near West Side. One study characterized Mexicans’ reaction to the shrinking spatial boundaries between them and Blacks as “dissatisfaction with ‘bad elements’ becoming more numerous” in their neighborhoods.Footnote 45 The rise of Chicano nationalism further complicated Mexican Chicago's identity. While a new activist generation wholly rejected whiteness and assimilation, an equal proportion of Mexicans continued to define themselves in contrast to Blackness by making “highly contested and locally dependent” claims to whiteness.Footnote 46

Puerto Ricans, Chicago's second-largest Latino ethnic group, settled on the Near North Side in neighborhoods such as Lincoln Park and Lakeview after decades of displacement due to urban renewal. They originally came to Chicago by way of higher education and state-sponsored labor migration as early as the 1940s.Footnote 47 Like other Latino groups, Puerto Ricans inherited a legacy of colorism from Spanish conquest that actively repressed their African ancestry. But their unique status as U.S. colonial subjects and the racialization of dark-skinned Puerto Ricans as Black allowed for greater acceptance of a racial minority identity over an ethnic one. “Despite the hostilities that existed between Puerto Ricans and black Americans,” argues Young Lords scholar Johanna Fernández, “their common experiences with racism opened up the possibility of shared identification.” Moments like the Division Street Riots of 1966, incited by the killing of a young Puerto Rican man by the Chicago Police Department, increased the racial proximity between Puerto Ricans and African Americans in Chicago compared to other Latinos.Footnote 48

Cubans were the third-largest group and lived mostly in Chicago's Far North Side, a location that created “the least amount of Black association” of all Latino groups.Footnote 49 Their distance from Black neighborhoods was intentional given that many Cubans arrived with professional backgrounds and actively aspired to ascend the class ladder, similar to white ethnics, and requiring a racial-spatial separation from Blacks. Like their compatriots in Miami, Cuban Americans in Chicago also espoused a conservative exile politics that favored Republican President Ronald Reagan's “get tough with Cuba” policy.Footnote 50 But unlike Miami, Chicago's most conservative and socioeconomically mobile Cubans quickly moved to the suburbs, a process of self-selection that resulted in a conservative majority paired with a large contingent of second-generation Cubans who were more progressive. Intra-ethnic encounters also shifted Cuban politics in Chicago. In author Achy Obejas's experience, she found that her community was in “constant contact with other Latinos … so we are constantly challenged in our thinking in ways that we wouldn't be in Miami.”Footnote 51

While these complex histories certainly influenced Latino preferences in the primary, the issue of anti-Blackness came to the fore in an unprecedented general election challenge. Winning the Democratic primary in Chicago had traditionally been tantamount to winning the general election. But for many in the political establishment, Washington's reform platform threatened to be the death knell for the city's patronage system. So, for the first time, Democratic leaders rejected their party's nominee by endorsing Republican Bernard Epton for mayor in an otherwise one-party city. And so went the majority of ethnic white voters that followed their aldermen to the Republican side, if just for one election. Epton, a lawyer and state legislator, exacerbated the racial divide of the primary. Notably, his campaign slogan “Before It's Too Late” warned of a Black takeover of city hall.Footnote 52 As one journalist observed of Epton's ads, “Political messages here are being delivered in code … after all, it would be impolite, maybe even impolitic, to come right out and say: ‘Now—before the blacks take over.’”Footnote 53

While Epton established the decidedly racial tone of the general election, Harold Washington confronted the fact that he had failed to build a true rainbow coalition. Washington won the primary thanks only to unanimous backing from the Black electorate, meaning that his mayoral aspirations now depended on a more deliberate Latino outreach strategy. The devastating realization that 87.3 percent of Latinos voted against Washington caused his campaign to revamp its approach and enlist the help of Latino staffers in the forty-nine days leading up to the April general election. Similarly, Rudy Lozano also found himself in an unexpected position, having lost in the primary election against the entrenched incumbent alderman, whose financial and organizational support from the Machine outmatched the young activist. Nevertheless, Lozano quickly transitioned to Washington's campaign full time and became his “main liaison to the Latino community.”Footnote 54 Now a campaign staffer, Lozano sought to unify the city's Latino electorate behind Washington.

Even though the Washington campaign desperately needed a concerted Latino outreach program, it still took over two weeks after the primary to adopt an official Latino campaign branch. Pressure from community and labor activists like Linda Coronado, also working for Washington, accelerated the establishment of the campaign's Latino Operations Department. Far beyond the task of bringing former Byrne and Daley supporters into the fold, the Latino Operations Department intentionally appealed to a singular pan-Latino constituency. For activists like Lozano and Coronado, who had been at the forefront of panethnic organizing during the previous decade, their involvement in the Washington campaign offered a unique opportunity to make manifest their vision of a shared Latino identity among Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and others. Thus, what news outlets framed as the Latino toss-up vote during the general election, the Washington campaign endeavored to transform into a cohesive Latino voting bloc.Footnote 55

More importantly, the Latino Operations Department sought to shepherd Latino voters through the citywide shift from ethnic politics to racial politics. Given Latinos’ liminal position in Chicago's racial hierarchy, the 1983 election forced them to decide whether their interests and values aligned more with Black or white voters. As such, the Washington campaign needed to convince Latinos that they would be best served by voting as a non-white minority bloc due to their racialized status in society and shared economic disadvantage with Blacks. With this task in mind, the department focused its efforts on the production of Spanish-language campaign materials, pushing panethnic messages in the media, and hosting Latino unity events.Footnote 56 These three priorities allowed the campaign to raise important issues concerning Latino ethno-racial identity and political consciousness through various outlets. All of these efforts addressed the pressing need to inoculate Latinos against the anti-Black rhetoric that influenced their vote in the primary and continued to hold sway in the general.

The Latino Literature Review Committee (LLRC) focused on the creation, publication, and distribution of campaign literature that targeted Latino voters, all printed in Spanish or bilingually. Evidence of the Washington campaign's panethnic mission can be drawn from even the most mundane process of designing a campaign button. At first, two designs were considered: 50,000 buttons with a Puerto Rican theme and 50,000 with a Mexican American theme. But a majority of committee members resisted this idea and instead “suggested consideration be given to one button with [a] design that covers Puerto Rican, Mexican, et al.”Footnote 57 This was also a practical consideration for the campaign. Rather than address each Latino subgroup separately, a panethnic appeal similar to that employed in presidential elections was more economical. The popular slogan “Sale el Sol para el Latino con Washington” [The Sun Rises for the Latino with Washington] ultimately took form as buttons and posters that graced jackets and lampposts across the city.

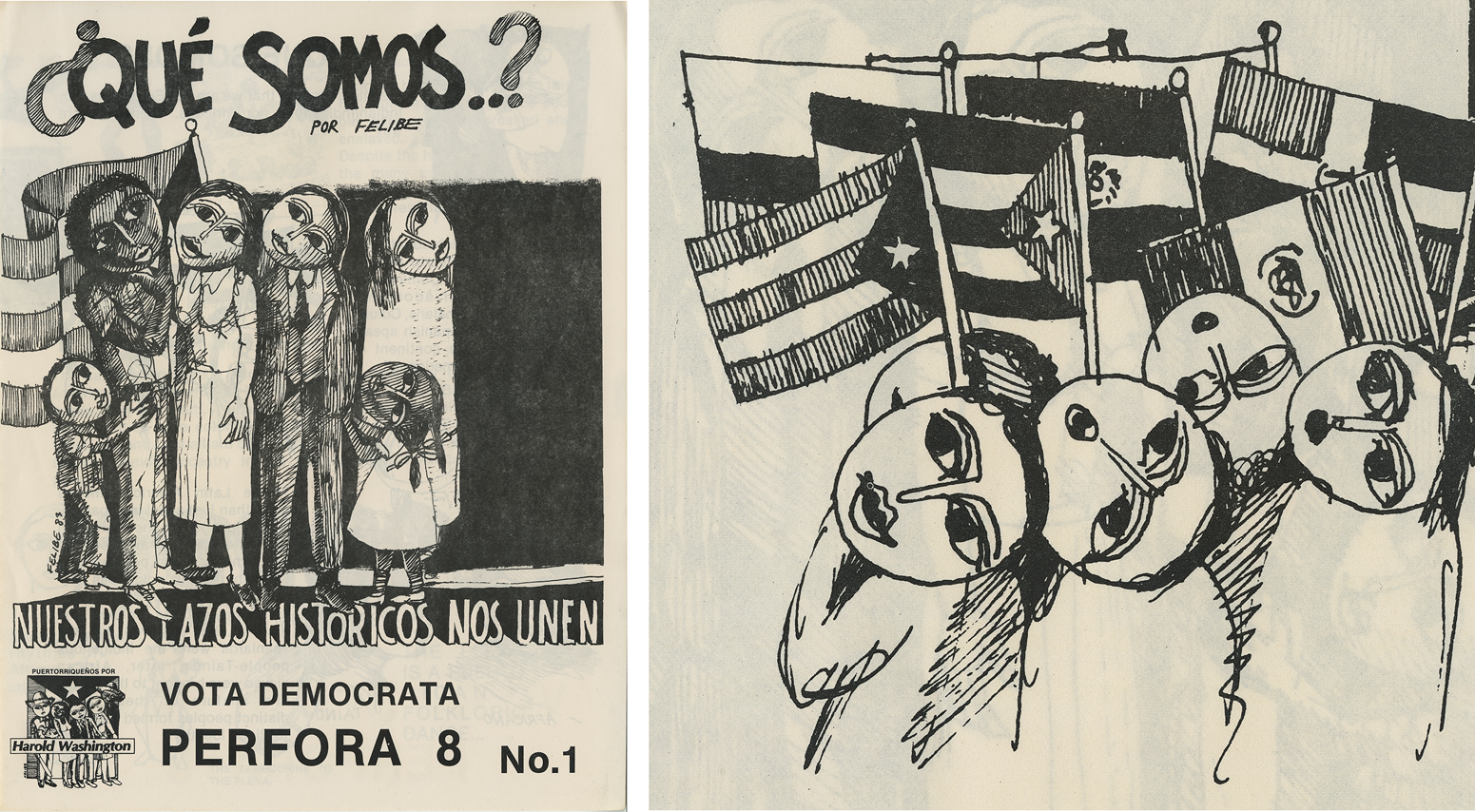

A flyer entitled “¿Qué Somos..?” [What Are We..?] captured the campaign's effort to foster a new kind of racial-political consciousness. “What Are We?” was brought up as a major campaign theme at the LLRC's very first meeting on March 9, and though participants suggested nationality-specific flyers, this particular message won out due to its “broad Latino appeal.”Footnote 58 “¿Qué Somos..?” was a beginner's guide to Latino identity that walked readers through the complexity of racial self-identification (Figure 3). “We know for sure that we are not Europeans, nor Indian/Indigenous nor Africans,” the flyer posited, “then, who are we?”Footnote 59 It explained that Latinos are descended from those three races, birthed from a shared history of racial mixing and colonization. It stressed the importance of unity between different groups of Latinos as a single racial minority group, despite differences in nationality and phenotype. This panethnic appeal was clearly visualized on the cover, which featured a multiracial group of Latinos and another image consisting of a united cluster of people holding up different Latin American flags.

Figure 3. Cover of Qué Somos? and cropped image of interior. From Qué Somos..? Mar. 1983, folder 5, box 25, HWMCR. Courtesy of Chicago Public Library.

“¿Qué Somos..?” also demonstrated the LLRC's commitment that all Latino campaign literature be “in line with Harold Washington's policy in developing the Black/Brown ties.”Footnote 60 The flyer ended its lesson on Latino identity by arguing that “Latinos face the same economic and social prejudice as black people. We must come together.”Footnote 61 This call for unity was a clear response to concerns expressed in progressive Latino circles regarding the influence of anti-Blackness in the primary, which risked hampering interracial unity if left unaddressed. The March newsletter from Puerto Rican education nonprofit ASPIRA discussed the need for a Black–Latino coalition after Washington's primary victory. Given the lack of Latino support for Washington during the primary, the organization saw the general election as a critical moment during which “the Latino population in Chicago must put aside their anti-black attitude.”Footnote 62 In this way, the campaign's targeted publications implied linked fate between Latinos and Blacks across the city, offering an alternate narrative to the public discussion about resource competition between racial groups.Footnote 63

The Washington campaign also engaged in a large-scale media effort that complemented the general literature distributed in Latino neighborhoods. Several Spanish-language and bilingual radio spots for Washington flooded the airwaves during the last week of the campaign in early April. Washington's Media and Advertising Coordinator Bill Zayas hired Rossi Advertising to target a panethnic Latino audience in both print and broadcast media. The firm's owner, Uruguayan Luis H. Rossi, was an early architect of Chicago's Latino media and panethnic consumer market who popularized promotional “Hispanic days” at major entertainment events and published the prominent newspaper La Raza.Footnote 64 It is no surprise, then, that Zayas and Rossi framed the “Latino vote” as a cohesive bloc with the power to swing the election. “The whole nation has its eyes on Chicago,” reads a half-minute radio spot, “… the future of the Democratic Party and the relationships among the minority groups will be determined by the April 12th election in Chicago. The Latino vote has been identified as one of the determining factors in this fight.”Footnote 65

Zayas developed a media strategy that emphasized the urgency of a unified Latino vote, and that engaged in more complex messaging around racial identity. More sensitive conversations of this nature took center stage in a bilingual periodical called El Independiente (The Independent). This newspaper aimed to provoke serious dialogue in Latino neighborhoods about racial self-identification. As one article argued, “It is ironic that some Hispanics do not want to admit that we are a discriminated minority, and foolishly and stubbornly insist on ‘Anglicizing’ themselves by associating with racist elements and practicing racism against Afro-Americans.”Footnote 66 Yet the paper was not merely a progressive voice; it was actually an in-house publication funded by the campaign—a unique and innovative strategy created to overcome the space and coverage limitations of traditional newspapers. El Independiente allowed the campaign to showcase the Black candidate's agenda for Latinos and broadened the coverage in Spanish-language print media. Much like the rest of the campaign, the newspaper stressed that Latinos were not just another assimilable white ethnic group.

Latinos for Washington events during the general campaign also contributed to the message of panethnic unity and interracial coalition building. Events ranged from intimate receptions for groups like the Hispanic Lawyers Committee for Washington to large-scale events such as the Latino endorsement rally held on March 18 at the Midland Hotel “comprised of Latinos who supported Daley and Byrne” ready to back the Democratic nominee.Footnote 67 Washington's campaign effectively broke the mold of ethnic politics by bringing together national origin groups and leaders across ethnic lines, bridging the divide between Mexican and Puerto Rican neighborhoods. The “Song of the People” fundraiser, for example, featured works from an array of Latino artists. Hosted by the “voceros de la comunidad” [“spokesmen of the community”] Juan Velázquez, “Cha-Cha” Jiménez, Rudy Lozano, and Juan Solíz—the first two men Puerto Rican and the latter two Mexican—the event constituted an intentional celebration of equal representation.Footnote 68

Nationally recognized Latino figureheads reinforced local leaders’ panethnic appeals. An early proposal for Latino campaign surrogates consisted of flying in members of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus such as Bob Garcia and Edward Roybal, as well as celebrities like Erik Estrada, Vicki Carr, and Rita Moreno.Footnote 69 The Latino Operations Department ultimately worked within the limited confines of its budget and made the necessary arrangements for a two-day joint visit by Grace Montañez Davis and Herman Badillo. Davis was the first Mexican American woman to serve as deputy mayor of Los Angeles and co-founded the Mexican American Political Association. Badillo was a New York politician and the first Puerto Rican elected to the United States Congress. The pair's itinerary included radio talks, grassroots campaigning, a dinner with Latino leaders, and a public townhall forum on “Latino unity.”Footnote 70 Their visit sought to project Mexican–Puerto Rican political unity and underscored the stakes of the 1983 election not only in Chicago, but also in the upcoming 1984 presidential race.

A visit to Chicago from New Mexico Governor Toney Anaya was the campaign's highest-profile Latino outreach event. The Mexican American governor agreed to be the keynote speaker for Harold Washington's “Hispanic Unity Dinner” on April 2, 1983, an event that brought in hundreds of supporters and thousands of dollars. A month before touching down in Chicago, Anaya had already called the city's Latino voters to action in a Spanish-language opinion piece for the Chicago Sun-Times entitled “Latinos: Es Hora de Aliarse” [“Latinos: It's Time to Unite”]. The op-ed foregrounded the panethnic unity rhetoric that he later emphasized during the visit. “There is great diversity among Latinos,” he wrote, “… I commit myself to unify the Latinos of this country so that our political presence may be felt.” For Anaya, just as for other Washington supporters like San Antonio Mayor Henry Cisneros and New York Congressman Bob Garcia, this public endorsement was rooted in a belief that Chicago's election had implications for the future, national viability of the Latino vote.Footnote 71

At the dinner, Anaya and Washington emphasized the connection between a unified Latino vote and a non-white minority identity. “As the nation's highest elected Hispanic,” Anaya asserted, “I am urging all Latinos to unify behind Harold Washington because only through him can we reverse some of the terrible injustices that have been done against Hispanics.”Footnote 72 By framing bread and butter issues such as equal employment, electoral representation, and bilingual education as “injustices,” Anaya prompted his audience to embrace a minority rights-based identity rooted in a civil rights struggle against oppression. The Governor's remarks also aligned neatly with Latinos’ policy priorities at the national level during the 1980s, which Anaya hoped would unite Latinos in Chicago.Footnote 73 Washington thanked Anaya for his support and reminded the audience that he could serve Latino needs only if he won their vote. “The Latino community has the potential to be a critically important swing vote,” Washington said. “The Latino vote is key to winning this election.”Footnote 74

Despite the Washington campaign's extensive effort to court Latino voters, controversies during the final stretch posed serious doubts about the prospect of Latino unity. Juan Andrade, Jr., director of the Midwest Voter Registration Education Project and the leading authority on Latino voters in Chicago, expressed skepticism: “The Hispanic vote is still a political wild card.”Footnote 75 One example of the significant resistance to Harold Washington includes the case of Chicago Public School Board President Raul Villalobos, who endorsed incumbent Jane Byrne during the primary, but withheld his general election endorsement with the empty excuse that he was “exploring and waiting to see if there is a commitment to Hispanics on the part of either candidate.”Footnote 76 Villalobos's reticence clearly reflected his distrust of a Black mayor because the only other candidate, Bernard Epton, had no Latino policy platform whatsoever.Footnote 77 In cases like these, anti-Black sentiment rooted in loyalty to the Machine explains Latino opposition to Washington in the absence of a competing Latino platform or outreach program from Epton.

Harold Washington's refusal to endorse Mexican American aldermanic candidate Ray Castro drew further Latino opposition. Castro served as the Seventh Ward Democratic Committeeman and was a candidate for alderman in the general election runoff against a Black opponent named William Beavers. Just four days before the general election, an explosive article in the Daily Calumet asserted that Castro's precinct captains called for an “open revolt” against Washington because he did not formally endorse Castro at a rally in the Seventh Ward. This confirmed observers’ suspicions that a Black mayor would sideline Latino interests. “If Washington doesn't have the nerve to endorse one Hispanic,” argued Castro staffer Sara Reyes, “then what do we have to expect when, and if, he becomes mayor?”Footnote 78 Though Washington ultimately endorsed Beavers, he did not take this or any other endorsement lightly, knowing the distrust it might provoke.Footnote 79 In fact, a televised Washington advertisement featured white alderman Larry Bloom talking about how Washington endorsed him over six Black candidates, proving that “he's got no favorites, he's got no hidden agenda,” and no preferential treatment toward Blacks.Footnote 80

National media outlets focused on Chicago's Latino voters the day before the general election. On April 11, an article in USA Today centered Latinos in its analysis of the Chicago mayor's race as the pivotal swing vote that was still heavily divided. “Hispanics could tip the scales,” the article argued, but their influence was said to be split by nationality wherein “Puerto Ricans favor Washington; Mexicans, Epton.”Footnote 81 That same day, the New York Times noted the extensive efforts by the Washington campaign to court Latino voters, while also reiterating the debate between Latinos “on whether they should view themselves as white or as a minority group.” Of course, the logic of race-based resource competition between Latinos and Blacks, which Washington so desperately sought to counter, endured. As local social services coordinator Christina Quintana told the Times, most Latinos she worked with supported Washington, but many still feared “Washington might fill all of the city jobs with blacks.”Footnote 82

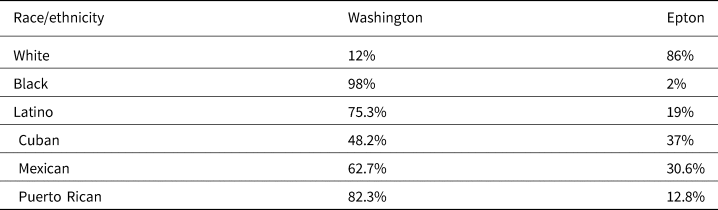

Almost 1.3 million people voted in Chicago on April 12, 1983. Harold Washington won a narrow victory with 51.7 percent of the vote and became Chicago's first Black mayor. Epton earned a shocking 48 percent of the vote, the most won by a Republican since 1927 and 200,000 more votes than the last three GOP mayoral candidates combined.Footnote 83 Ultimately, a racial divide sharply polarized Black and white voters—a divide that Latinos awkwardly straddled (Table 2). Though Washington won 75.3 percent of Latino votes, this majority support was stratified by national origin. Puerto Rican areas like the Thirty-First Ward overwhelmingly sided with Washington. Mexican American wards marginally leaned in Washington's favor, more than Cubans but to a lesser degree than Puerto Ricans. Rudy Lozano's Twenty-Second Ward, which encompassed the largest Mexican population paired with a robust IPO, was still the only district that Washington won with less than 60 percent of the vote and proof positive of Mexicans’ unresolved identity politics.Footnote 84 In the end, the uneven Latino support for Washington revealed the variance of anti-Blackness across national origin subgroups and their ongoing struggle to solidify panethnic political unity.

Table 2. Chicago general election mayoral results by race/ethnicity, 1983

Source: Juan Andrade, Jr. and Wilfredo Nieves, Final Exit Poll Report, Chicago Mayoral Election, April 12, 1983 (Columbus, OH, 1983), 4–10; Alkalimat and Gills, “Black Power vs. Racism,” 148–50.

When compared to the unity of the Black vote, the Latino bloc that appeared at the polls was far from the Latino landside expected for the “rainbow coalition” candidate. Not only did one-quarter of Latino votes go to the Republican candidate, many more Latinos stayed home altogether. Compared to a record-high turnout rate of 81 percent across all voters, about 40 percent of registered Latino voters did not go to the polls. The persistence of anti-Black sentiment likely contributed to lower turnout in the form of boycotting Washington, as suggested in the minutes of a “Hispanic political roundtable” from early March. The roundtable was composed of moderate Mexican American leaders and supporters of Mayor Byrne during the primary. According to the Washington campaign's invited envoy Peter Earle, the meeting's discussion focused on the stance that “Latinos should exercise a demonstration of potential political power by boycotting the election.”Footnote 85 Whether a boycott or just apathy, Latinos severely underperformed as an equal partner in the Black–Latino coalition of 1983.

Existing interpretations of the 1983 election speak of Harold Washington's unifying impact on Latinos, referring to his candidacy as “the spark that ignited electoral participation,” “a turning point for Latino political empowerment,” and “a milestone … for black-Latino relations.”Footnote 86 Granted, Latinos engaged more in electoral politics after 1983, but their unity, in relation to each other and to Blacks, stalled and worsened. Latino voters were once again divided as Mayor Washington faced Jane Byrne in a two-way race during the 1987 Democratic primary. Polling by the Chicago Tribune found again that “many Hispanics believe the mayor has given them short shrift while he concentrates on improving conditions for blacks.”Footnote 87 Latino support in the 1987 primary signaled prevalent distrust of a Black mayor, but Washington narrowly edged by with 55 percent of the Latino vote to Byrne's 45 percent.Footnote 88 White backlash resulted in another contentious general election with the third-party candidacy of Democratic Party chairman Edward Vrdolyak. In the end, Washington reconsolidated his tenuous coalition in 1987 with 77 percent of Latino votes and 54 percent of the total electorate.Footnote 89

Harold Washington's sudden death in 1987 and the scramble to elect a replacement further complicated the ongoing debate about Latinos’ precarious position along the Black/white political divide. The 1989 special election between white candidate Richard M. Daley and Black candidate Timothy Evans, however, confirmed Latinos’ decisive racial-political alignment with whites. While many believed the Latino community would join Blacks in supporting Evans as Washington's legacy, most Latinos staked their future on the old Machine's heir. This was certainly the case for Puerto Rican alderman Luis Gutiérrez, who, despite having been mentored by Harold Washington, endorsed Daley for mayor. Labeled a “defector” and “traitor” by progressive Latino leaders, Gutiérrez's defection from the rainbow coalition was in fact a precursor to the white–Latino electoral coalition that kept the new Daley Machine in office for twenty-two years.Footnote 90 Latinos decisively “calculated that there is more to be gained by supporting a White Mayor than a Black Mayor,” and their consistent majority support in Daley's re-election campaigns underscored Latino voters’ enduring misgivings about Black political leadership.Footnote 91

Exposing the influence of anti-Black sentiment on Latino political behavior reveals the underappreciated importance of primary elections. Latinos actively preferred white primary candidates Byrne and Daley in 1983, but an even greater opposition to hard-line, conservative Republicanism outweighed and masked these preferences in the general election. Scholars’ neglect of the primary contest, as well as disproportionate focus on general election results, help to explain why anti-Blackness has been inadequately addressed in previous studies of the 1983 election. Similarly, Democratic presidential nominee Barack Obama's majority share of the Latino vote (67 percent) in the 2008 U.S. general election quickly overshadowed the fact that Latinos voted for white candidate Hillary Clinton over Obama at a rate of two-to-one in the Democratic primaries.Footnote 92 Despite espousing racial resentment on par with whites, Latino opposition to both Washington and Obama in primary elections still allowed the Black candidates to win the majority of the Latino vote against Republican candidates.Footnote 93 Primary elections, then and now, thus merit more careful attention as sites of anti-Blackness in electoral politics before party loyalty overrides it.

Popular understandings of the 1983 Chicago mayoral election also emphasize the majority Latino support behind Harold Washington in the general election, without mention of earlier divisions. As Rudy Lozano's life gave us insight to this historical moment, his death is our guide to the persistent mythos regarding Black–Latino unity. Lozano was killed in his home in June of 1983 at the age of thirty-one, just two months into Harold Washington's first term.Footnote 94 The motive behind Lozano's murder remains unknown, but progressive community organizations and publications quickly settled on politically motivated assassination, making Lozano a political martyr of the Washington campaign's rainbow coalition. The 7th Ward Independent, for example, speculated that “behind Rudy's murder stand economic and political interests who feared the Black-Latino-Poor White alliance he was helping to build around the Washington campaign.”Footnote 95 The tragedy made headlines as thousands marched in honor of the deceased activist and paid their respects at his funeral.

A newly inaugurated Mayor Washington joined the mourners and declared that “if the coalition of Chicago which came with my election is due to anyone, it is due to Rudy Lozano.”Footnote 96 In addition to Mexicans, Puerto Rican community leaders also turned to Lozano's legacy as evidence of Latino panethnic unity. Speaking to Spanish-language newspaper El Mañana, Reverend Jorge Morales lauded the fallen activist on the one-year anniversary of his death. “Rudy was not Puerto Rican,” Morales said, “but he won the respect of the community through his commitment to our struggles.”Footnote 97 Lozano was continuously memorialized in death, especially by the Twenty-Second Ward Independent Political Organization, which regularly dedicated its yearly conventions in his honor. As Chicago journalist Jorge Casuso summarized in 1986, “Lozano has become more important to the Hispanic community in death than in life.”Footnote 98 Washington soon joined the pantheon of the rainbow coalition and was venerated in similar fashion when he died of a heart attack in 1987, shortly into his second term.

To this day, progressive leaders hearken to the memory of Washington and Lozano's partnership as the consummate model for Black–Latino political unity, as illustrated by the career of U.S. Representative Jesus “Chuy” Garcia. Close friends with Rudy Lozano, Garcia entered the world of Chicago politics through the independent political movement and went on to serve in elected positions at the local, state, and, currently, federal levels. In 2015, Garcia sought to rekindle the Washington coalition as a candidate for mayor and forced the first mayoral runoff in Chicago's history against incumbent Mayor Rahm Emanuel. Garcia's 2015 campaign literature and rhetoric emphasized his connection to Washington and the early independent movement, with frequent invocations to the rainbow coalition of the 1980s. Mainstream media outlets also framed Garcia's bid as a modern-day iteration of Washington and Lozano's coalition.Footnote 99 “With Chuy running,” said Lozano's surviving widow Lupe, “it's like a spirit of Rudy that keeps living on.”Footnote 100 Though Garcia ultimately lost the election and barely unified 66 percent of Latino voters, his candidacy was a testament to the staying power of 1983's political memory.

This reappraisal of the rainbow coalition narrative has sought to complicate the romanticized interpretation of the 1983 election prevalent in academic and popular accounts, identifying what one scholar has called the “cracks in the rainbow.”Footnote 101 As we have seen, Latino support for Harold Washington was stratified, anomalous, and fleeting from the very beginning—a fact obscured by the rose-colored glasses of memory that have overemphasized panethnic and interracial unity. In June 2020, the American Historical Association released a statement that called on historians to “confront this nation's past” through our work, a response to the ongoing crisis of police brutality against African Americans that also applies here.Footnote 102 Cases like the 1983 Chicago mayoral election demonstrate that anti-Blackness was, and continues to be, a fundamental aspect of modern urban politics. Confronting the past in this instance requires us to begin difficult and uncomfortable conversations about Latino history, identity, and politics that acknowledge both the inspirational coalitions as well as deep-seated racial resentment. Ultimately, the vision of unity articulated by Lozano and Washington will remain tenuous as long as the necessary reminders of Latino disunity are few and far between.

Moments of disunity during the 1983 election have much to teach us when we apply political scientist Cristina Beltrán's reimagining of Latino panethnicity as a verb rather than a label. “Subjects marked ‘Latino’ do not represent a preexisting community just waiting to emerge from the shadows,” Beltrán argues. “Instead, ‘Latino politics’ is best understood as a form of enactment, a democratic moment in which subjects create new patterns of commonality and contest unequal forms of power.”Footnote 103 In this way, we must not confuse 1983 as confirmation of a primordial Latino unity or the natural partnership between Blacks and Latinos. Instead, Latino politics, then and now, calls for deliberative consensus building and constant self-interrogation. Latino Chicagoans’ vigorous debate about their racial identity and their relationship to each other is a case study in this messy practice of Latinidad—a history that reminds us that Latino panethnicity must be continually questioned, developed, and remade.