In 1948 the United Jewish Appeal, the most important vehicle for Jewish fundraising in the United States, released a film depicting the plight of Jewish refugees who had left Europe for Israel, only to be placed in tents in the desert due to a lack of housing. While pictures of human misery flash across the screen, a stern-voiced narrator scolds his viewers for not fulfilling their campaign pledges:

You can't explain to a sick child why this must be…. This baby never heard of the United Jewish Appeal, of unfilled quotas, unpaid pledges. All she knows is the pain that is always with her…. Who is to blame? Did you have a share in putting these people into the tents, into these lines? … Perhaps the agencies of the United Jewish Appeal haven't done enough…. Or does the fault lie with American Jewry? … We must act now, today. Cash is the only thing that will get them out of these camps. Cash is the only thing that will give them a new home. Cash for the United Jewish Appeal will fulfill our promise that they shall not be homeless again.Footnote 1

The film transparently attempted to induce feelings of both compassion and guilt in the viewer. The manipulation of emotion, however, is only successful if the recipient of the message is receptive to an emotional appeal. If the viewers of this film had felt no sympathy for the Holocaust survivors, no qualms about dwelling in comfort while their co-religionists suffered in the sun-scorched desert, the film would have failed to achieve its goals. But the emotional message of this film hit its target—and was replicated in a vast body of American Jewish fundraising material in 1948. In the year of the creation of the state of Israel, the United Jewish Appeal raised $150 million, a sum worth ten times that in today's currency. Not only was it the organization's most successful campaign to date, the total was almost equal to all American Protestant, Catholic, and nonsectarian donations for overseas relief in that year.Footnote 2

As the case of American Jewry in 1948 demonstrates, methodologies from the history of emotions can illuminate the study of ethnic and national attachments. The vast literature on ethnicity, nationalism, and other forms of what sociologist Rogers Brubaker has called “groupness” is filled with references to emotion, yet it tends to take emotions at face value rather than explore their multidimensionality, the processes by which emotions bond together or break apart, and the transformative effect of varying mixtures of emotions on group sensibility.Footnote 3 In turn, scholars of political emotion—in which a person's well-being is conceived of as dependent upon that of a larger entity—have usually examined collective identities through the lens of negative emotions such as fear, anger, and hatred, and have not taken sufficient account of the solidarity generated by positive emotions such as love, hope, compassion, and pride.Footnote 4

The study of groupness has much to gain from work on the history and sociology of emotion. In his pioneering book, The Navigation of Feeling, historian and cultural anthropologist William Reddy developed the concept of an “emotional regime,” which he defined as “a set of normative emotions” that provide “a necessary underpinning of any stable political regime.”Footnote 5 In this book and subsequent work, Reddy writes about territorially delimited states and empires, leaving us uncertain as to how nonstate actors without centralized authority (such as members of an ethnic minority) form, express, and dispute political emotions.Footnote 6 In contrast, historian Barbara Rosenwein and sociologist James Jasper have conceived of emotion within communities whose social cohesion is voluntarist and whose points of discursive production are diffuse. Communities with shared goals create emotional bonds within amorphous social movements unbounded by a state.Footnote 7

The concepts of emotional regime and emotional community can usefully be applied to American Jewry in 1948. American Jewish institutions lacked the coercive authority of a state, but they effectively elicited mass support for Israel via well-coordinated and heavily publicized fundraising campaigns.Footnote 8 These campaigns honored supporters and shamed shirkers, and their publicity drove home a powerful emotional message that Israel's survival—and the future of Holocaust survivors languishing in Europe—depended upon American Jewish largesse. Fundraising institutions, however, could succeed only by responding to the feelings of prospective donors, and expressions of solidarity with Israel in the Jewish press were laterally reinforcing as well as directed from the top down. American Jewish public discourse on Israel took its cue from the new state's leaders, who were in constant contact with diaspora Jewish leaders and opinion makers. Nonetheless, despite attempts at top-down emotional management, the emotional vocabulary of American Jewry in 1948 was not uniform. A variety of emotional expressions attested to the grassroots strength of American Jewish support for the newly created state.

Though it is impossible to penetrate the consciousness of millions of American Jews, quantitative evidence of the 1948 campaign's success, alongside qualitative evidence from archival correspondence, newspaper articles, and public speeches, document the emotional messages disseminated by Jews in positions of influence. The evidence is limited to articulated expressions of feeling (a term used here as a synonym for emotion), which cannot prove that activists’ emotional messages were directly responsible for the actions of the Jewish public. The correlation between the fundraising campaign's urgent appeals and its results, however, is strong, and further research may recast that correlation as causation.

There is a substantial literature on American Zionism's role in Israel's creation, but it focuses on the leaders of American Jewish organizations, and in particular their successful lobbying of the Truman administration to support the partition of Palestine and the creation of a Jewish state.Footnote 9 A secondary elite of community activists, journalists, and rabbis disseminated the call to support Israel into their communities. Their influence lay primarily in the mobilization of funds. The United Jewish Appeal's fundraising campaign of that year has received much attention, but the existing scholarship focuses on its methods and outcome, overlooking its emotional messaging and apparent impact.Footnote 10 Moreover, the existing literature on American Jewry in 1948 concentrates on the period up to Israel's declaration of statehood on May 14, thereby underplaying shifting perceptions and reactions of American Jews to events on the ground during the Arab-Israeli war that lasted on and off until March 1949.

Emotional bonds between Jews in America and abroad preceded 1948. At the fin de siècle, the flood of philanthropic giving by bourgeois American Jews for the benefit of recently arrived immigrant Jews from eastern Europe was motivated equally by compassion and anxiety. Sympathy for their co-religionists’ suffering and poverty blended with fear lest the newcomers be perceived as uncouth and outlandish, thereby stoking antisemitism and threatening the hard-won social status of the established Jewish bourgeoisie. After World War I, socially mobile immigrant Jews in the United States were deeply attached to their fellow Jews in eastern Europe and gave lavishly to reconstruct communities that had been damaged or destroyed.Footnote 11

Interwar American Zionism focused on the construction of a new community in Palestine rather than on the reconstruction of old communities in Europe. Reconciling commitments to the needs of Jews abroad and confidence in a robust future for their own communities, American Zionists interpreted their cause as a humanitarian project that embodied progressive American values and that they could support without being accused of dual loyalty. As Jeffrey Shandler has written, whereas European Zionists saw in a Jewish national home “a solution to their inherently problematic existence,” American Zionists conceived of Palestine as a home for other Jews, not for themselves. “Palestine's halutzim [Jewish pioneer laborers] were exemplars for American Jews to admire and support, rather than imitate.”Footnote 12

Post-1945 Zionism would retain much of this upbeat emotional rhetoric, but it was intertwined with anguish over the genocide of European Jewry and fear for the survivors. The latter was the source of American Zionism's stunning increase in popularity. Between 1919 and 1939, total membership in Zionist organizations seldom passed 100,000. In 1940, however, affiliations leaped to over 170,000 and then skyrocketed, reaching almost 1 million in 1948. One-third of American Jewish adults now belonged to Zionist organizations—the same percentage as those who belonged to synagogues.Footnote 13 Zionism still had competitors and detractors within the American Jewish community, but it had become mainstream, if not hegemonic.Footnote 14 The Reform movement had distanced itself from its historic antagonism toward Jewish nationalism, and Jewish leftist anti-Zionism had been weakened by the Soviet Union's support at the United Nations for the partition of Palestine and the creation of a Jewish state.

Emotion was a motor of social action in driving American Zionism's transition into a mass movement. Emotional language, the meaning of that language, and the social reception of emotion shift across time and space.Footnote 15 Emotions are bundled and intertwined; one can catalyze another, and individuals may express multiple, conflicting emotions simultaneously. The subjects of this article employ language that is familiar to our ears, but the bundled emotions within their rhetoric require disentangling, and the balance of emotions shifted over time. For American Jews in 1948, fear for the fledgling state of Israel blended with expressions of brash confidence in its military capacity, and feelings of solidarity with Israel and compassion for Jewish refugees in Europe were laced with survivor guilt. Solidarity served as the base from which these emotions developed, for without a sense of commonality between American and Israeli Jews, the former would neither have cared for, nor taken pride in, the latter.

Solidarity and Pride

The American Jewish press greeted the partition resolution of November 29, 1947, with jubilation. These feelings connoted the fulfillment of a long-held aspiration and thus the resolution of yearning, alongside a sense of the sublime. In the months that followed the passing of the resolution, the feeling of fulfillment was qualified by anticipation and expectation, which enhanced solidarity with the fledgling state. According to the Detroit Jewish Chronicle in March 1948, fundraising for Palestine united all of the Jewish denominations, and the city's Orthodox community announced it would pray for divine intercession during the upcoming Fast of Esther on the day before the holiday of Purim, itself a celebration of deliverance from calamity.Footnote 16 Israel's declaration of statehood in May evoked feelings of joy laced with pious sentiments of reverence, thankfulness, dedication, and awe. At a youth event celebrating Israel's creation, a University of Chicago student said, “When I saw the flag of Israel rise in the air, I felt the crowd melt in a maze of collective emotion. We were as one.”Footnote 17 The prominent rabbi Milton Steinberg issued a Jewish call to arms on behalf of the Jewish state.Footnote 18

This spirit of unity was the guiding force behind the United Jewish Appeal (UJA), which raised funds for three separate organizations with distinct purviews: the United Palestine Appeal (UPA), which worked for Jews in Palestine; the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC), which aided Jews in Europe and North Africa; and the United Service for New Americans (USNA), which focused on Jewish refugees in the United States.Footnote 19 The UJA national campaign's Report to Members, a weekly mimeographed pamphlet, reported in January 1948 that “the news from abroad, which arouses the deepest sympathy and sense of solidarity, establishes the essential atmosphere for campaigning on its highest and most sacrificial level.”Footnote 20 The UJA was determined to tap into and enhance that solidarity through its 1948 national drive, which it called its “Year of Destiny” campaign, with a fundraising goal of $250 million. This represented a marked increase from previous targets of $100 million and $170 million in 1946 and 1947 respectively, and a massive jump from wartime fundraising, which had totaled $125 million over the period 1941–1945. The main purview of the postwar campaign was relief for Jewish Holocaust survivors and refugees, but whereas the 1946 campaign emphasized care for those in Europe, thereafter the focus switched to resettlement in Palestine. In 1946 proceeds were to be divided roughly 60/40 between the JDC and UPA, but in 1948 the proportions were reversed.Footnote 21

Negligible amounts were to be allocated for resettlement in the United States. Large-scale Jewish immigration to the United States faced formidable opposition from Congress and public opinion. In 1945, President Truman had issued a directive that Displaced Persons (DPs, victims of involuntary migration who could not be safely repatriated to their homelands) be included in existing immigration quotas. Congressional legislation of 1948 allowed for the admission of 400,000 DPs, but with a strong preference for agricultural laborers, thereby excluding most Jews. Sympathy and solidarity on the part of American Jews would not suffice to bring a wave of European refugees to American shores. Instead, UJA leaders assumed, they would be cared for in Europe until the moment was ripe for them to make new lives in the Jewish state.

The 1948 UJA campaign did not reach its goal, but it did raise $150 million, as opposed to $110 million in the previous year (with $30 million of that sum coming from previously unpaid pledges in 1946).Footnote 22 In order to reach its unprecedented target, UJA leaders cultivated an atmosphere of controlled frenzy as each local federation took it upon itself to surpass the previous year's intake. An editorial in the Detroit Jewish Chronicle in January implored American Jews to go “over the top” in the UJA campaign. A week later, an editorial in the San Francisco Jewish Weekly Bulletin expressed confidence in the “ability and willingness of the average Jew in America to grasp current problems and the needs of the hour—and to translate them into sacrifice.” In February, Boston's Jewish Advocate featured a poem describing members of the American women's Zionist organization Hadassah as “our soldiers.” The Philadelphia Jewish Exponent described volunteer fundraisers as “an army of destiny.” And in early May, an advertisement in the San Francisco paper urged, “[I]f you have doubled your contribution—when you could easily afford to triple it—you haven't given enough.”Footnote 23

The UJA's campaign echoed both Jewish fundraising drives in the interwar period and the American government's bond drives during World War II. It emphasized engaging the “total Jewish community,” flooding it with advertising in local newspapers, radio programs, billboards, placards, and literature “on the most extensive scale in history.”Footnote 24 The layout, style, and content of the UJA weekly Report to Members manifested energy and commitment. Telegraphic paragraphs communicated news from Jewish communities throughout the United States, striving to exceed previous years’ fundraising tallies. Stakhanovite donors (and entire communities) were singled out for praise. Donation was a demonstrative, active response to a state of profound concern for the fate of one's fellow Jews. As Seymour Tilchin, a Detroit lawyer and founder of that city's Jewish Chronicle explained, the solution for feeling “confused, disturbed, emotionally exhausted” by events in Israel is to donate—but only to recognized, community charities like the UJA.Footnote 25

In February 1948, the UJA claimed that Palestine urgently needed $50 million in cash, an amount approximately equal to unpaid pledges from the 1947 campaign. An illustrious trio—UJA Chair Henry Morgenthau, Jr. (former secretary of the treasury of the United States), Herbert Lehman (former governor of New York and director-general of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration), and Golda Meyerson (the head of the political department of the proto-governmental Jewish Agency for Palestine)—spoke via telephone hookup to UJA leaders in communities nationwide.Footnote 26 Lehman spoke directly of Palestine's defense needs, expressing pride in the men and women who were fighting for Palestine and the need to provide arms for what he called the “tragically endangered” Jews of Palestine. If American Jewry did not give these “defenseless” Jews the means to fight off the Arab states, Lehman warned, the result would be the “utter destruction of a brave people.” Meyerson spoke of an “unequal war” between the wealthy and armed Arab states and Palestine's Jewish community, which had “no officially recognized militia” and “does not now possess the means of defense.” “We must ask Jews the world over to do for us what America did so generously for England in the World War,” she proclaimed.Footnote 27 Within two months, $30 million in cash donations had come in, with $20 million more from local federations that had borrowed heavily against future receipts.

The sense of urgency, pressure, and crisis among the Jewish fundraising elite led them to justify a harsh, even brutal, approach to those unwilling to contribute to the cause. In June 1948, eleven Jews in Mexico City sent a letter of complaint to the Zionist Organization of America and to the anti-Zionist American Council for Judaism about a recent fundraising campaign spearheaded by Mexican Zionists that “has been characterized by intimidation and the use of coercive methods.” People who refused to give or who did not honor their pledges were subject to mock public trials, public shaming and shunning, and a “lynch spirit.” “Mob tension was provoked and stirred up to a pitch of brutality and terrorism. One of the defendants … was badly beaten up.” A “blacklist” of recalcitrant Jews was to be sent to the government of Israel.Footnote 28 Elkan Myers, President of Baltimore's Jewish Welfare Fund, was perturbed by the letter and by similar stories about rough justice being meted out to reluctant Jewish donors in Argentina. He sent a copy of the letter on to the UJA Executive Vice-Chair, Henry Montor.Footnote 29

Montor's reaction was swift and unyielding. Fundraisers for Jewish causes, he wrote, “feel that their own fate, the fate of their whole people, is interwoven with the fulfillment of the cause.” In the face of “indifference” or “hostility” from potential donors, the fundraisers grew angry and resentful in response.Footnote 30 If a Jew chose to remove himself entirely from the community, that was one thing, but any Jew who continued to remain within the community was justly liable to coercion by fundraisers, just as, in a time of war, he would be assessed a levy for military defense.

The alleged shaming and shunning acts in Mexico, Montor contended, were carried out throughout the United States. A Jew, he wrote, may not be allowed to join a country club if his donation has been deemed to be too paltry. At social gatherings, public pressure was placed on donors to raise their pledges. To a European Jew used to more subtle forms of fundraising, Montor wrote, “the scenes enacted at our big gift dinners or parlor meetings are causes for horror.” But hard-sell fundraising tactics, Montor claimed, were both common and necessary throughout the United States, including Myers’ own community of Baltimore. Turning the tables on his correspondent, Montor asserted that Myers had been acting with the “conviction that the salvation of literally hundreds of thousands of human beings is literally involved in what you do—or fail to do.”Footnote 31

Montor, Lehman, Morgenthau, and hundreds of local UJA activists formed a nationwide grid of fundraisers who appealed to Jewish conscience and solidarity, offered honors to those who gave generously, and shamed those who fell short. Jews who wanted to be respected members of their communities, and especially those who claimed positions of authority, influence, and respect within them, were pressured to contribute. Banquet halls and boardrooms were sites for emotional performances that induced ebullience and panic.Footnote 32 The tactics worked. In March 1948, UJA campaigns in Baltimore, Los Angeles, and Newark led to more than 125 gifts that were on average twice as much as the previous year's, and three- or fourfold increases were common.Footnote 33

The main recipients of the UJA's attention were well-to-do Jewish businessmen, who represented a minority of American Jewry as a whole. The gifts from Baltimore, Los Angeles, and Newark in March ranged between $300 and $75,000, with average amounts in the low five figures—substantial sums at a time when median family income in the United States was $3,200.Footnote 34 It is difficult to quantify how many Jews in more humble circumstances donated to the UJA in 1948. For the New York Jewish Federation's fall campaign for its own welfare institutions, of 23,500 donors, more than 20,000 gave less than $250, whereas only 550 gave more than $2,500. Two percent of the donors provided more than half of total receipts.Footnote 35 It is likely that large numbers of American Jews made similar small contributions to the UJA campaign, although they were not acknowledged in its fundraising literature.

Insight into non-elite Jews’ attachments to Palestine comes from the archival records of the UPA's largest beneficiary, Keren Hayesod (the Foundation Fund). Keren Hayesod was the fundraising arm of the Jewish Agency for Palestine, whose purview included the construction of infrastructure and settlement of new immigrants. The files of Keren Hayesod are thick with correspondence from Jewish individuals throughout the United States, ranging from major cities to small towns, in which people of all ages asked throughout 1948 for printed information on Palestine, maps of Israel, photographs of the country and its people, and Keren Hayesod calendars. Letter writers made donations of as little as one dollar. Jewish educators reported that they were building up new curricula about Israel. In the fall of 1947 and winter of 1948, Keren Hayesod put on a Palestine exhibit at Radio City Music Hall that was enormously popular and offered visitors the opportunity to purchase craftwork and objets d'art infused with the spirit of the new Zionist culture in Palestine.Footnote 36 A man from Long Island, who was both a passionate Zionist and gardener, helped himself at the exhibit to five pounds of Palestinian soil, which he mixed into his vegetable patch.Footnote 37

As a sign of popular concern for the Jews of Palestine, many writers to Keren Hayesod's New York office were keen to send food parcels to the country—often, though not always, for relatives. The feelings of compassion and worry that underlay their shipments of food put the new Israeli government in an uncomfortable position. When the secretary of Keren Hayesod travelled to Israel in October 1948, she was told by Treasury Secretary Eliezer Kaplan that “the impression should not go out to the Jewish world that the Jewish community of Israel is poor, and, therefore, [in] the need for packages.” At the same time, he did not mind word getting out that “there was a food shortage because of the war situation.”Footnote 38 In other words, Kaplan wanted to craft the emotional message sent by Israel to American Jewry that the country was experiencing a war-related crisis that should elicit solidarity, not chronic misery that would elicit pity.

UJA fundraisers employed an emotional vocabulary that was allied with a state-generated emotional regime. Meyerson's fundraising speeches bore the weight of her stature as a senior official in Palestine's Jewish proto-government, but she also spoke to her audience as an American, born and raised in Milwaukee. Speaking in Miami in February 1948, she said that the city “reminds me of Tel Aviv,” but “[h]ere one doesn't hear any shooting by day and night.” Meyerson proposed a clear division of labor between her audience and the Jews of Palestine: “This is your war, too … [b]ut we do not ask you to guard the convoy. If there is any blood to be spilled, let it be ours…. Remember, though, that how long this blood will be shed depends on you.”Footnote 39

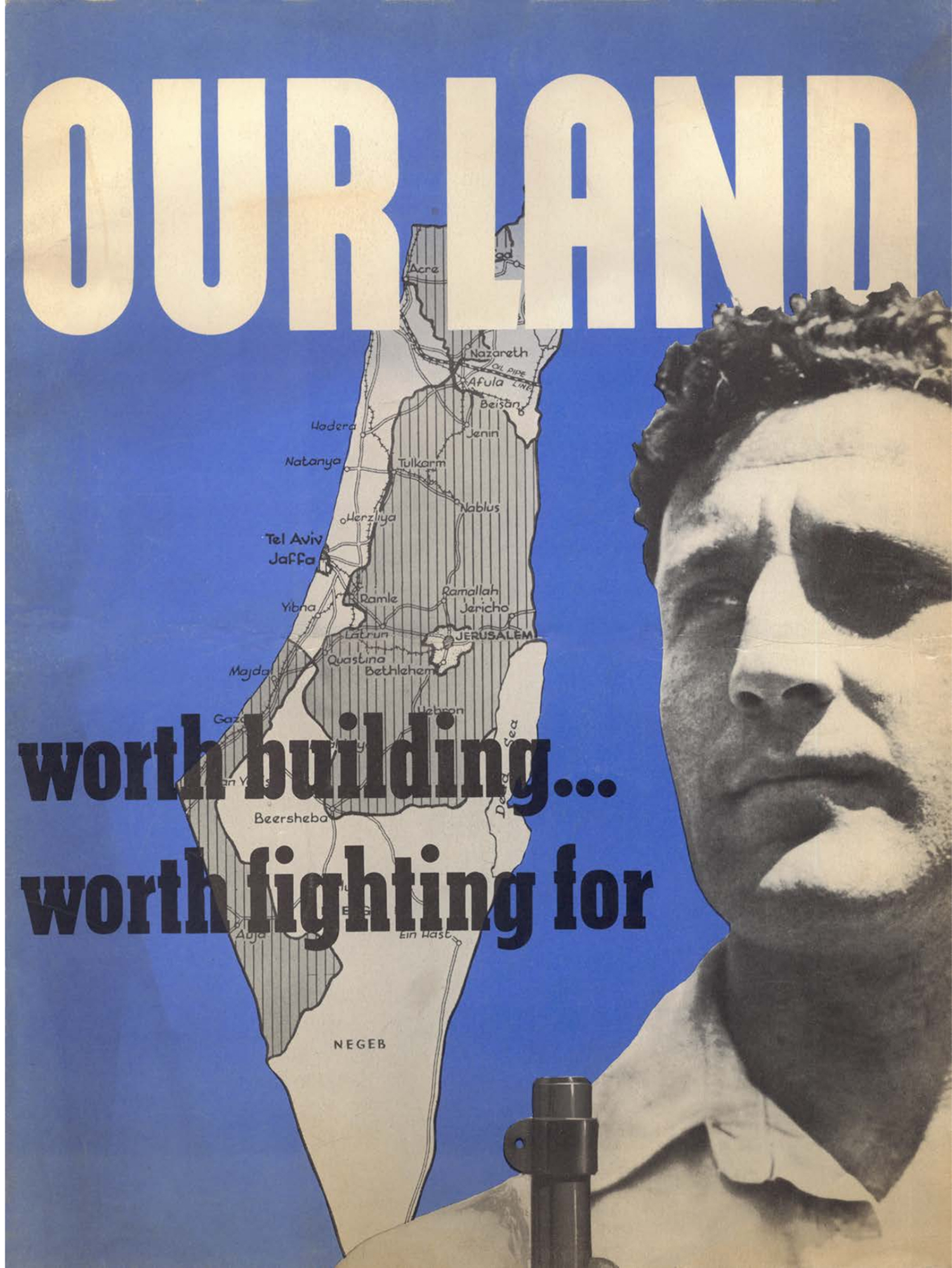

UJA posters conveyed a similar message of committed, yet unequal, partnership. A fundraising poster from late 1947 or early 1948 depicts a handsome, chiseled, and armed Hebrew fighter of decidedly European appearance against a background of a map of Palestine featuring the partition resolution's borders (Figure 1). Palestine appears to be literally resting on the young man's shoulders.Footnote 40 Both the imagery and the wording (“Our Land/Worth Building/Worth Fighting For”) evoke a sense of common struggle (for our land) as well as pride and gratitude from the American observer. Later in the war, such feelings were passionately expressed by Daniel Rudstein, whose column in the Boston Jewish Advocate told of a visiting group of “nine men and women of the heroic Haganah, defense army of Israel.”Footnote 41 The Haganah fighters “marched stiffly down the garden corridor—with heads erect, eyes straight ahead and stiffly swinging their arms in the proud march of the youth of Israel. The crowd stood on its feet and cheered for here were members of the heroic group that bravely withstood the onslaught of six Arab armies … and held the borders of Israel strong and determined.”Footnote 42

Figure 1: United Jewish Appeal fundraising poster, late 1947 or early 1948. (Source: Federation CJA [Combined Jewish Appeal of Montreal], “A Journey Through 100 Years,” http://www.federationcja.org/100/decades/1947-1956.)

Such outbursts of pride in and solidarity with a foreign state left Jews open to accusations of dual loyalty. Zionists had long been sensitive to this possibility. In 1915, the most famous Zionist in America, the future United States Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, declared an insoluble bond between Zionist and progressive American values. Throughout the interwar period, American Zionists presented the Jewish national home as a pioneer republic, an infant sibling of the United States.Footnote 43 In 1948, these views went far beyond the Zionist community. As Amy Kaplan and John Judis have noted, in 1948 American liberal publications such as The Nation and The New Republic presented Israel as an outpost of American progressivism and civic virtue.Footnote 44 This rosy image was not diminished by the young state's failure to follow an American developmental model. In late 1948, the Jewish newspapers expressed pride in the imminent promulgation of an Israeli constitution that would ensure Israel's status as a Western democracy and would have an American-style bill of rights.Footnote 45 When the constitution was shelved, the pro-Israel press was silent.

Solidarity with Israel, although prevalent, was not omnipresent. The Detroit Jewish Chronicle published occasional pieces by Alfred Segal, a non-Zionist, humanist, and columnist for the Cincinnati Post, who in the spring of 1948 supported plans formulated by the United Nations and the Truman administration to jettison partition in favor of a United Nations trusteeship for Palestine.Footnote 46 The San Francisco Jewish Weekly Bulletin reflected the domination within the city's Jewish community of Reform Judaism, which had historically featured a prominent anti-Zionist streak. Accordingly, it was willing to publish the views of cautious non-Zionists like Lloyd Dinkelspiel, head of the city's Jewish Welfare Fund, as well as of more stridently anti-Zionists like George Levinson of the American Council for Judaism.Footnote 47 The other newspapers, however, pushed back hard against Zionism's opponents, Jewish and Gentile alike. The Detroit paper criticized Segal sharply, and a letter to the editor declaimed that Segal “made her sick.”Footnote 48

The image of what Kaplan calls “Our American Israel” was a co-production of Jews and Gentiles alike. It is telling that Meyerson, the most influential Palestinian Jew on the American scene in 1948, was herself of American origin and connected on that level with her audience. Constructing Israel as America's youngest sibling served Israel's interests by promoting fundraising, but the emotional language that the fundraising efforts employed responded directly to American Jewish sensibilities. “Our American Israel” not only provided Jews with a defense against accusations of dual loyalty but also justified expressions of disappointment, frustration, and even anger against Zionism's opponents. Those negative feelings carried over to any government, including their own, for offering anything less than unqualified support for the Jewish state.

Righteous Anger

Between 1945 and 1948, American Jewish leaders frequently presented the Zionist struggle for a Jewish state as one against British imperialism.Footnote 49 During the first half of 1948, the Jewish press escalated its rhetoric, routinely accusing the British of harboring anti-Zionist and pro-Arab sympathies. (According to an editorial in the Detroit Jewish Chronicle, the British were a greater enemy than the Arabs.Footnote 50) The Jewish newspapers also attacked the U.S. government over many actions, such as ordering American citizens in Palestine to turn in their U.S. passports, taking punitive actions against those who fought for the future Jewish state, declaring an embargo on the sale of arms to the combatants, or backing away from support for partition in the winter of 1948 in favor of a United Nations trusteeship. Although the State Department and unnamed “oil interests” were the most frequent objects of attack, President Truman himself was not spared.

In February, the Boston Jewish Advocate, commenting on the American government's retreat from support for partition, declaimed that “what is going on in Palestine is the rape of a UN decision which was reached with moral support.” The paper excoriated the United States for engaging in “treachery, catastrophe, and moral insolvency.”Footnote 51 A month later, Detroit's Nathan Ziprin wrote of U.S. policy, “The hurt is too deep, the wound too painful, the insult too heavy, the betrayal too unbelievable…. The United States stands with the Arabs in shearing Jewish hopes, in subjecting our men, women, and children in Palestine to slaughter by semi-civilized peoples and in frustrating a dream which stood as a pillar of light in Jewish life over the centuries.”Footnote 52 In April, according to an editorial in the Chicago Sentinel, Palestine was in the same position as the Warsaw Ghetto exactly five years previously: Palestine's Jews would either die en masse or “write a new and glorious page in the development of democracy.” Which scenario would occur, according the editorial, lay in the hands of the newspapers’ readers, who were called upon to give tirelessly of themselves and their resources.Footnote 53 Balfour Peisner, a Detroit lawyer and Jewish activist, described Palestine under British rule as a “police state” no better than Nazi-occupied Europe.Footnote 54

Boris Smolar, a widely syndicated and influential journalist and editor-in-chief at the Jewish Telegraphic Agency (JTA), noted in October that Jews were irritated with both presidential candidates, Thomas Dewey and Harry Truman, and that Israel had no choice but to look after itself.Footnote 55 The implied message behind Smolar's column was that American Jewry would stand by Israel regardless of the U.S. government's desires or actions. The Jewish press featured a notable absence of the gratitude toward Britain and the United States that had been abundant after the promulgation of the Balfour Declaration and its endorsement by President Woodrow Wilson. U.S. support for the partition resolution and Israel's declaration of statehood elicited only occasional expressions of thanks to the Truman administration, and gratitude toward the United Nations was even harder to come by. The world had changed enormously since the early days of the British Mandate, when Zionists routinely compared the Balfour Declaration to the Magna Carta, simultaneously an acknowledgment of human rights and liberties and an act of benevolent, royal grace.Footnote 56 In the wake of the Holocaust, the need for a Jewish state appeared urgent and apparent—a matter entirely of right, and not, as it had been previously, a blend of right and privilege. Failure to acknowledge that right was a source of unequivocal moral condemnation by American Jewish activists.

Supporters of Israel took comfort from the fact that despite shifting winds within the U.S. government, public opinion was on the Zionists’ side. Just after the 1947 partition resolution, the Jewish press expressed satisfaction that, according to public opinion polling, the vast majority of Americans favored partition, as did influential newspapers like The New York Herald Tribune and The Washington Post. In case of an Arab-Jewish war, only a small fraction, some 10 to 12 percent, would support the Arabs.Footnote 57 Popular support was but one reason why, despite widespread anger and distrust toward the British and American governments as well as the United Nations, fear for Israel's survival was mitigated by confidence that the Jewish state would, in fact, prevail.

Projecting Confidence

In the autumn of 1947, Arab states threatened a war of annihilation against the Jewish state should the United Nations recommend partition. The coordinated Zionist response was that the Arab states lacked the ability to attack and that Palestine's Arabs had no desire to take up arms against the Jews. In late September, a consortium of Zionist groups known as the American Zionist Emergency Council issued a memorandum asserting that the Arab states would not risk attacking a Jewish state without either Soviet or British assistance, neither of which was in the offing.Footnote 58 The confidence implied in such statements was in fact a stratagem to dissuade the UN from distancing itself from partition lest it cause a bloodbath. Zionist leaders continued to downplay the prospects of a multistate Arab invasion through the winter of 1948, when Palestinian fighters and volunteers from neighboring countries inflicted heavy damage on Palestine's Jewish communities. As mentioned above, the American administration considered walking back from partition and supporting a United Nations trusteeship over the territory. The Zionist leadership wanted to avoid this scenario, preferring to risk a military conflict that, they hoped, would end in the achievement of Jewish statehood.

The American Jewish press expressed little apprehension about a multistate Arab invasion. Was the press doing the bidding of Zionist leaders and attempting to create an emotional regime of resolute calm in the face of an impending war? That may be so, although it is more likely that journalists got their material from the same sources (e.g., the Jewish Agency's political department, the Zionist Organization of America's public relations department, and JTA press releases) than that they engaged in overt collusion. The variety of topics covered and approaches taken in the reportage in the winter of 1948 suggests the former was the case. In December 1947, Nathan Ziprin, whose weekly column appeared in more than twenty Jewish newspapers, assured readers that Arab resistance against Zionism was weakening, and that if the Palestinian leader Amin al-Husseini were to try to take control of the new Arab state, Arabs opposed to him would ally with the Jews.Footnote 59 In December, the San Francisco Jewish Weekly Bulletin observed that the recent Arab League summit in Cairo agreed to form a multinational Arab Liberation Army but that no Arab state would commit its own national forces to a war in Palestine. Berl Coralnik, a writer for the Chicago Sentinel who became the JTA's chief correspondent in Palestine, reported that the Arab League was considering accepting partition and would not invade Palestine if the United Nations introduced a police force into the territory.Footnote 60 The Boston Jewish Advocate informed its readers in January 1948 that King Abdallah of Jordan planned to take over the territory of Palestine's Arab state—and, by implication, leave the Jewish state alone.Footnote 61

Much of what the Jewish press reported goes against the grain of the subsequently formed collective memory of American and Israeli Jews alike regarding the balance of forces during the war between Israel and Arab states that began on May 15, 1948. That memory was one of David versus Goliath—a small Israeli state, poorly armed and equipped, fighting against an alliance of Arab states. Confident assessments of Israeli military power, however, were common in the American Jewish press on the eve of and during the war, and these assessments strongly resemble those made decades later by historians such as Benny Morris.Footnote 62 In October 1947, a newspaper published by American supporters of the Haganah claimed that with the exception of the Jordanian Arab Legion, the Arab state armies were “for the most part ill-trained, poorly equipped, badly disciplined and under-nourished. They have few modern weapons and fewer men trained to use them. An air force is practically non-existent, as is a navy. There are no arms factories and no replacements for equipment.”Footnote 63 In the following months, nonpartisan Jewish community newspapers offered similar analyses.

In Philadelphia in late April, Hillel Silverman, an American journalist and Haganah volunteer, claimed in a public talk that Arab fighters were poorly trained and equipped, and that the Haganah was far superior. The Detroit Jewish Chronicle wrote in May that the Zionists had at least 45,000 well-trained and well-equipped troops, ready to handle “any combined offensive by the Arab states.” Writing in the Chicago Sentinel, Hirsch Wolfson noted that, with full conscription, that number could leap to 100,000 or more. A fortnight after the multistate Arab intervention began, Morris Bromberg, a frequent contributor to the Chicago Sentinel, highlighted the Arab states’ military weakness, lack of coordination, and need to keep troops at home to defend unpopular monarchs. In the war, he wrote, some indefensible border communities might fall, but Israel would triumph.Footnote 64

There was a direct link between changing facts on the ground and Israeli policies, on the one hand, and the American Jewish representation of these developments, on the other. In July and August, Israel began to claim jurisdiction over western Jerusalem, although according to the United Nations partition resolution, the entire city was to be internationalized. Until the late summer, the American Jewish press reported on the exclusion of Jerusalem from the Jewish state matter-of-factly and without consternation—itself a remarkable matter given Jerusalem's symbolic meaning for Jews the world over.Footnote 65 Soon after Israel's provisional government made a formal claim on western Jerusalem on September 16, however, the American Jewish press began to present western Jerusalem as an indisputable part of the state of Israel. The Detroit Jewish Chronicle now claimed that Israel without Jerusalem would be like the United States without New England—a nation with its heart cut out.Footnote 66

As confidence in an anticipated victory turned into an assessment of an assured one, the American Jewish press supported Israel's retention of western Jerusalem and other territories taken beyond those allocated to the Jewish state by the United Nations. Nonetheless, the press allowed for a measure of debate on the matter. Detroit's Jewish paper ran a regular “Man on the Street” column, which consisted of interviews with passers-by on a street corner in a heavily Jewish neighborhood. (Although these interviews can hardly be said to provide a representative sample of Jewish public opinion, they are interesting for what questions the paper thought appropriate to ask, and what sort of answers the paper was willing to publish.) In September, three interviewees were asked if Israel should retain or surrender land it conquered beyond the partition proposal's borders. One interviewee favored retaining the land under any circumstances, while the other two endorsed returning it in exchange for peace with the Arab states.Footnote 67

Over the course of the war, the press expressed deep concern about the well-being of Israel's Jewish population, but trepidation was as likely to stem from political dissent within Israel as from war with the Arabs. These expressions of fear, like those of confidence we have examined thus far, imply the construction of a Zionist emotional regime. The newspapers were sympathetic with the Zionist Labor movement, which dominated the leadership of the embryonic Jewish state. The newspapers’ sympathies indicated less an embrace of social-democratic ideology so much as admiration for the ideals of pioneer settlement that the movement claimed to embody.Footnote 68Accordingly, both editorials and opinion pieces dismissed the Irgun, a militia associated with right-wing Revisionist Zionism and at odds with the Labor Zionist Haganah, as fascist, chauvinistic, and dangerous to the unity of the state. In late 1947, the Boston Jewish Advocate featured denunciations of Irgun members as terrorists who were blowing up innocents.Footnote 69 In June, a JTA dispatch described the Haganah's sinking off the coast of Palestine of the Altalena, a ship carrying arms for Irgun fighters, as a necessary act to prevent civil war, while the Detroit Jewish Chronicle headline blared, “Israeli-Irgun Fighting Rages—Tel Aviv in Panic as Clashes Spread.”Footnote 70 A number of letter-writers, however, mounted spirited defenses of the Irgun and its leader, Menachem Begin.

The newspapers, like the Zionist leadership in Palestine, also expressed fear for the future of Jews in the Arab world. In early 1948, Boris Smolar asked, but did not definitively answer, whose needs of the moment were greater: Jews in Arab lands or DPs in Europe?Footnote 71 In March, the Chicago Sentinel and Philadelphia Jewish Exponent carried a wire story that a million Jews in Arab lands faced genocide—what the Sentinel called persecution on a Hitlerian scale—at the hands of Arabs. The papers anxiously covered persecution of Jews in Libya and riots in Morocco in June, in which scores of Jews died.Footnote 72 “Egypt's Jews Face Annihilation,” blared a headline in the Detroit Jewish Chronicle in August.Footnote 73

Last but not least, the papers expressed fear of persisting or growing antisemitism in the United States itself. Leaders of the American Jewish Committee in the 1950s were deeply concerned about antisemitism.Footnote 74 Such concerns were manifest during the months surrounding the United Nations partition proposal for Palestine. In November 1947, the Detroit Jewish Chronicle urged its readers to “sit up and take notice” of a series of articles in The New Republic claiming that antisemitism in the United States was in some ways worse than it had been when Hitler came to power.Footnote 75 According to the Jewish press, Israel would help American Jews fight antisemitism in two different ways. First, it would absorb the European Jewish survivors whose exodus to the United States could exacerbate antisemitism. Second, by displaying courage and resolve, a willingness to work and fight for their land, the Jews of Israel would provide their American counterparts with a powerful apologetic tool. These expressions of anxiety were homegrown and mingled with the morale-building messages coming from the war zone in Palestine.

Feelings About the Palestinian Refugees: From Compassion to Callousness

During the war's first several months, expressions of fear of Israel's Arab enemies were mitigated, and even overwhelmed, by a rhetoric of compassion for Palestinian refugees. Although the Jewish press printed stories of Arabs killing Jews in Palestine, there was substantially less reportage on the activities of Palestinian armed forces than in prominent newspapers such as The New York Herald Tribune or The New York Times. Only in letters to the editor did one encounter outright Arabophobia, as in one letter to the Boston Jewish Advocate from February 26, 1948, regarding the battle between Palestine's Jewish community and “hundreds of thousands of savage barbarians.”Footnote 76 In contrast, many stories in the Jewish newspapers emphasized Palestinian-Arab desires for co-existence. These articles invoked an old Labor Zionist argument, dating back to the 1920s and picked up by American Zionist leaders, such as Stephen S. Wise and Abba Hillel Silver, that anti-Zionism was the work of reactionary effendis, without whose interference Jews and Arabs in Palestine would live in harmony.Footnote 77 In February 1948, a cartoon printed in both the Chicago Sentinel and Boston Jewish Advocate depicted Amin al-Husseini, armed with a rifle, physically placing himself between a seated Bedouin and a Western-dressed young male Zionist.Footnote 78 According to the Detroit paper, the Arab fighters killed in Palestine in early 1948 were “invaders” from Syria, as Palestinian Arabs were peaceful and did not want war. Even when the paper offered an unusually grim assessment of the military threat facing the future Jewish state, Palestinian Arabs were described as “a loose mass of individuals,” juxtaposed against the highly organized Jews.Footnote 79

In December, the Boston Jewish Advocate claimed that the Haganah was deployed to protect areas of Palestine where Jews and Arabs lived amicably, and it would implement mutual defense agreements between Arab and Jewish communities to staunch both violence and flight.Footnote 80 According to the Sentinel, the custodian of absentee property, who had been appointed in Israel, would protect the property of Arabs who had left the country under pressure of Arab propaganda. After the end of hostilities, the custodian would return to the Arabs not only their land but also any profits gained by temporary Jewish usufruct. For the Sentinel, it was a “cardinal point” of Israeli policy to welcome 400,000 Arab refugees back to their homes.Footnote 81 When the first United Nations–imposed truce went into effect in June, the Philadelphia Jewish Exponent gushed that the Haganah had no “temptation to acquire by force those sections of Palestine, historically Jewish, which in its wisdom the UN saw fit to assign to others.”Footnote 82 In that same month, the Sentinel wrote that Jews never dreamed of an all-Jewish state, and that Jews and Arabs in Israel could have lived together in peace if the local Arabs had not been manipulated and coerced by their leaders.Footnote 83 Multiple reasons were given for Arab flight—panic, threats from their own leaders, or, as the Chicago paper wrote in May, fears that their cause was lost and that a Jewish offensive would crush them: “A road of Arab despair winds eastwards across Jordan”; “They fear Jewish offenses are crashing through weakened Arab volunteer resistance.”Footnote 84

These views simultaneously reflected, distorted, and concealed actual events on the ground. The figure of 400,000 refugees quoted by the Sentinel in April matched a June 30, 1948, Israeli military-intelligence estimate of the total number of Arabs displaced within historic Palestine over the course of the first half of the year. But that same memorandum notes that the most important factor behind Arab flight was “direct Jewish hostile actions” and that all told, 70 percent was caused by Jewish forces, as opposed to “some 5 percent” due to Arab evacuation orders.Footnote 85 None of the American Jewish newspapers mentioned an important source of Arab forced migration: panic induced by the massacre by Irgun forces of more than 100 Palestinian civilians in the village of Deir Yasin, on the outskirts of Jerusalem, in April 1948.Footnote 86

By April 1948, kibbutzim were working abandoned Arab lands, but in contrast to what was reported in the American Jewish press, they had no intention of returning the lands to their previous tenants, nor of repaying them the profits from their usufruct. At a meeting of the provisional government on June 16, Foreign Minister Moshe Shertok (he took the Hebraized name Sharett in August) said of the refugees that “they are not coming back … they need to get used to the idea that this is a lost cause and this is a change that cannot be undone.”Footnote 87 Over the next two months, this view became official governmental policy.

The sentiments expressed in the American Jewish newspapers reflected public statements by Israeli leaders to the American government, the United Nations, and the American Jewish community. In an interview with the San Francisco Jewish Weekly Bulletin in December 1947, Haganah commander Teddy Kollek (the future mayor of Jerusalem), a “clear-eyed, lean, blond farmer of 36,” said that most Arabs in Palestine regretted the Arab states’ rejection of partition and that those few who did protest were inspired by Amin al-Husseini. In Detroit in May 1948, Meyerson asserted that the Palestinian Arabs were not fighting against the Jewish state and that trouble was caused only by invading forces. Meyerson added that Israel had no territorial ambitions beyond the partition boundaries and that “Israel would return any territory captured by the Israelim [sic] which was not included in the UN partition plan.”Footnote 88

Despite these humane sentiments, after the second round of Arab-Israeli fighting in July 1948, the language of compassion and mercy in the American Jewish press started to blend with, and ultimately shifted over to, one of toughness and decisiveness. The newspapers began to write of a population transfer, with Palestinian Arabs going to Arab lands, and Jews from the Middle East coming to Israel. “It would be well for both races if Arab refugees did not return to Israel,” wrote the Detroit Jewish Chronicle. They should be compensated, but their very numbers “would remain a threat to peace and the ideal of a Jewish state.”Footnote 89 The American Jewish press appears to have been echoing rhetoric coming from Israel, as by early August statements about the refugees that had previously been made only in private were now uttered in public. In early August, the diplomat Abba (formerly Aubrey) Eban said that the Arab states should take care of the Palestinian refugees just as Jews would provide for the Jewish ones, and Sharett said that barring a formal peace agreement with the Arab states, readmitting the refugees would be dangerous, even though they had fled due to external forces for which they were not responsible.Footnote 90

In April, a Hadassah publication had claimed that the “Arabs were not forced from the country nor were they threatened with persecution but left on the advice of their own leaders.”Footnote 91 In the late summer, this view became common.Footnote 92 In August the editor of the Philadelphia Jewish Exponent reacted angrily to a New York Times report that Israeli forces drove Palestinians from their homes. Using numbers cited at the time by UN mediator Folke Bernadotte, he wrote: “Driven? … By whom? Surely you do not mean to imply that the Jews of Palestine ordered these 300,000 out of the country.” He asserted that the Arabs were promised that they would not be harmed if they had stayed but made no mention of prospects for their return.Footnote 93

Nonetheless, the earlier spirit of compassion persisted. On August 12, a Boston Jewish Advocate's editorial assured readers that although the Arabs and British both bore responsibility for the Arabs’ flight, their homes were intact, and that although their fields were being plowed by Israel's fighting men, the Arabs “can look forward to resumption of normal life in Israel when hostilities end.”Footnote 94 A week later, an editorial titled “The Quality of Mercy” in the Detroit Jewish Chronicle exuded sympathy, declaring that Jews, of all people, could appreciate the Palestinians’ tragedy. The editorial assured Palestine's Arabs that they were not unwanted in Israel, that their homes and businesses were secure, and that they could and should go back.Footnote 95 Even if the American Jewish journalists were responding to cues from the Israeli government, they were not uniformly parroting a government line but expressed their own points of view.

More often than not, however, after mid-August, American Jewish public opinion turned against the refugees. In late August, the “Man on the Street” columnist for the Detroit Jewish Chronicle asked if Israel should allow the refugees to return to their homes. Three of four people interviewed said no.Footnote 96 In October, the Boston Jewish Advocate declared that the refugees could not return outside of a comprehensive peace treaty. A military officer who contributed regularly to the paper argued that the refugees “knew” that their homes had been destroyed or taken over, that they could not go back, and that they would willingly go to Syria or Iraq, but Arab states feared resettling refugees because they had absorbed liberal ideas from the Zionists.Footnote 97 The Boston paper also asserted that Arabs fled en masse from the Galilee “without reason” and said nothing about letting them back.Footnote 98 By this time Seymour Tilchin of the Detroit Jewish Chronicle had lost all sympathy for the refugees, whose flight was “as unnecessary as it is incriminating,” having been caused by the machinations of Arab politicians, not fear of the Jews. The lucky Arabs, he wrote, were those who stayed behind, enjoying high wages and health care. The Sentinel's Morris Bromberg also blamed the Palestinians for their fate, writing that if they had stayed, they would have enjoyed civil liberties and minority protection.Footnote 99

The switch in focus by the American Jewish press from the refugees to those Arabs who stayed behind in Israel and allegedly enjoyed the benefits of its largesse was prompted by the international Zionist Organization's president, Chaim Weizmann, who offered mollifying words that although the Zionists did not know why the Arabs left, “We must do everything possible for them now. They are citizens of Israel now and they will be citizens in every sense of the word. Certainly, we will never disenfranchise anyone because he is not a Jew.”Footnote 100 In December, an editorial in the Philadelphia Jewish Exponent praising Israel's treatment of its Arab citizens explicitly drew on material from the public relations department of the Zionist Organization of America.Footnote 101

Like writers for the American Jewish press, in the fall of 1948 UJA officials justified indifference toward the refugees. Rumors that Palestinian officials had ordered the Arab residents of Jaffa and Haifa to flee were presented as blanket orders applied throughout the country.Footnote 102 Morgenthau, the chair of the UJA, held a press conference at which he called Amin al-Husseini “Hitler's great friend” and, speaking about the first phases of the war, claimed that “he [Husseini] led the Arabs out of the villages even before the fighting started, and urged them to leave.”Footnote 103 (In fact, al-Husseini was in Cairo at the time.) In the minds of Zionist officials, anger toward al-Husseini, accompanied by a denial of responsibility for the refugees’ fate, transformed abandoned Arab property into a boon that could be exploited without moral qualms. In 1949, a UJA budget planning document calmly noted that “by the end of September 1949, about 50% of the total immigration since the establishment of the State was accommodated in abandoned Arab places.”Footnote 104

The about-face in American Jewish reportage on the war in the last third of 1948, and the cool, technocratic language of the UJA in the following year, did not mean an end to statements of sympathy with the Palestinian refugees. American Jewish discourse on Palestine was similar to a remark by Meyerson in May 1948, after visiting Haifa in the aftermath of the Palestinian exodus from that city, that the Arabs’ abandonment of their homes reminded her of the tragedy that had befallen European Jewry.Footnote 105 Like Meyerson, American Jewish activists presented Palestinian flight as a regrettable tragedy, but they coded its causes and consequences in such a way that they bore no guilt, so the new state of Israel could in good conscience take advantage of the windfall in land and housing stock that had come its way. Within the state's solidifying borders, the Israeli government had created an emotional regime, inspiring the Jewish population to sacrifice and either disregard Palestinian suffering or shift blame to the Arabs themselves. The penumbra of that regime encompassed American Jewry as well.

Between Compassion and Guilt

In 1948, the American Jewish press and the UJA appealed to potential benefactors’ emotions through a language of moral obligation. According to the San Francisco Jewish Weekly Bulletin, the UJA's “Year of Destiny” campaign was a call to “join the growing forces of American Jewry hearkening to the crisis of stricken brethren destitute abroad.” The situation in Palestine is shifting and confusing, the paper contended, but the one constant was the DPs and their need for American Jewish help.Footnote 106 At the bottom of Palestine-related stories in the paper, there were small bold captions such as, “You give; they live.” The Detroit Jewish Chronicle saw in the United Nations partition resolution a “cure” for the problems of world Jewry, and that cure was relief for the refugee crisis.Footnote 107 These sentiments were reinforced by Meyerson's nationwide fundraising speeches, which framed donations to Israel as assistance for “the greatest resettlement program in the history of the Jewish people.”Footnote 108

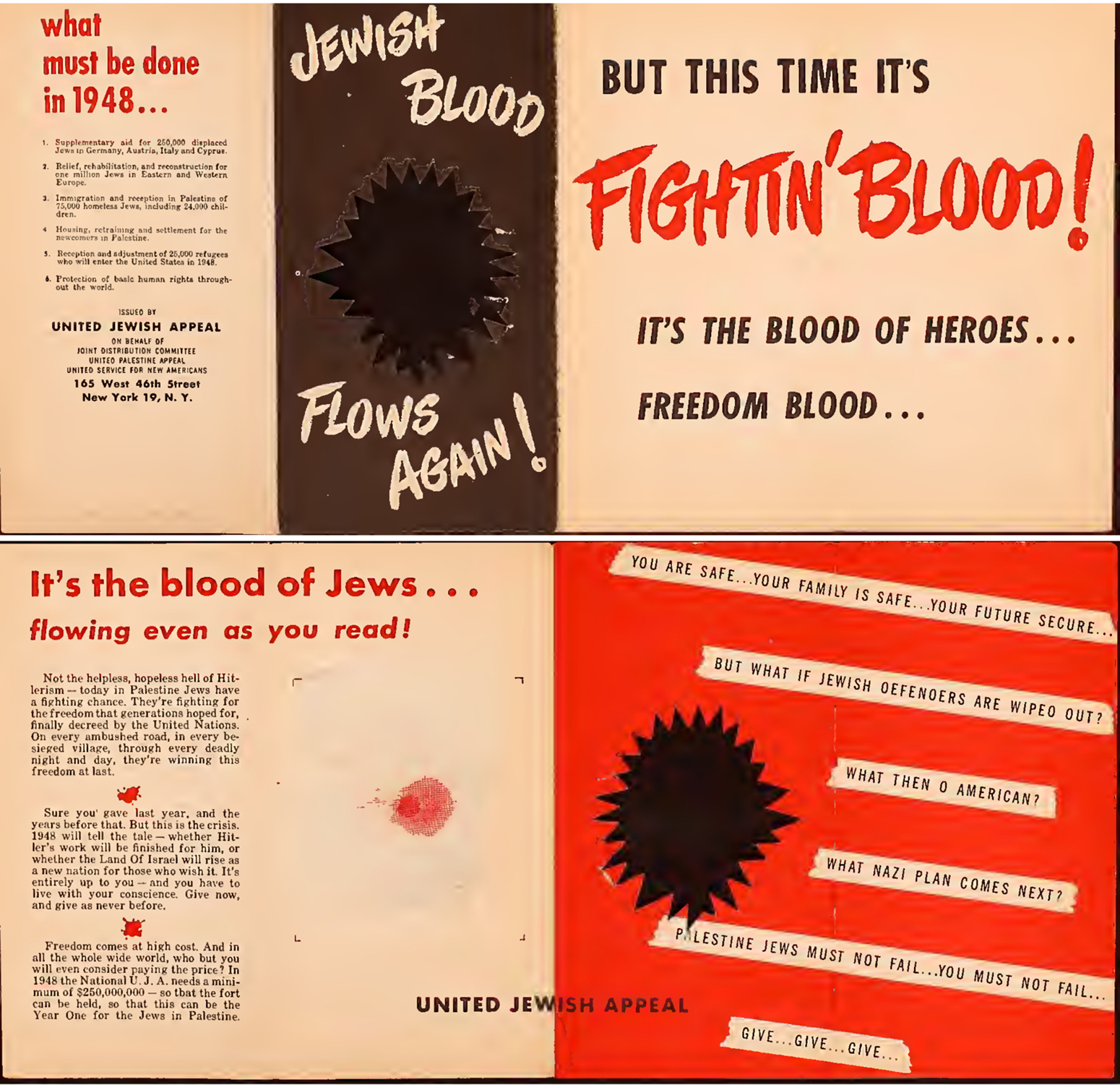

Although the Jewish press offered detailed coverage of the battles in Palestine, the war was usually not central to UJA fundraising strategy. There was a striking exception: a June 1948 UJA pamphlet titled “Jewish Blood Flows Again!” (Figure 2). The pamphlet reads, in large, bold, red letters:

But this time it's FIGHTIN' BLOOD! It's the blood of heroes…. Freedom blood…. It's the blood of Jews … flowing even as you read! Not the helpless, hopeless, hell of Hitlerism—today in Palestine Jews have a fighting chance. They're fighting for the freedom that generations hoped for, finally decreed by the United Nations. On every ambushed road, in every besieged village, through every deadly night and day, they're winning this freedom at last…. 1948 will tell the tale—whether Hitler's work will be finished for him, or whether the Land of Israel will rise as a new nation for those who wish it. It's entirely up to you—and you have to live with your conscience. Give now, and give as never before.Footnote 109

Figure 2: United Jewish Appeal pamphlet, 1948. (Source: United Jewish Appeal, Jewish Blood Flows Again! [New York, 1948]. Digital copy provided by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.)

On another page, thin strips of block letters resembling a telegram blare: “You are safe … your family is safe … your future secure … But what if Jewish defenders are wiped out? What then O Americans? What Nazi plan comes next? Palestine Jews must not fail. You must not fail … Give … Give … Give.…”Footnote 110

This pamphlet was not content to remind Jews of their obligations to their brethren in Palestine but instead imposed upon its readers a massive burden of guilt. Emmy Hermann, the secretary of the Jerusalem head office of Keren Hayesod, found the pamphlet abhorrent, not because of its guilt-inducing rhetoric so much as its “bloodthirsty propaganda” and spectacularly bad taste.Footnote 111 Most of the UJA's fundraising material was indeed in better taste, but it was no less artfully designed to evoke feelings of guilt. This literature usually focused less on the Jews of Palestine than on the DPs in Europe. Concern for the DPs formed a lowest common denominator that could motivate American Jews to give generously to Israel. When planning the 1948 UJA campaign, Henry Montor consciously chose to concentrate fundraising efforts in the hands of organizations that represented all of American Jewry rather than specifically Zionist ones.Footnote 112 The discursive equivalent (and effect) of this institutional positioning was an intertwining in fundraising appeals of the refugee issue and the creation of the state of Israel. Louis Golden, director of the Boston Combined Jewish Appeal, dramatically illustrated the power of this approach when, on the eve of the Jewish new year in 1948, he daringly secularized the holiday liturgy's solemn acknowledgment that God would decide who in the next year would live and who would die:

In most recent [sic] years it is we who have held that fate as it has concerned our brethren in Europe, and we have decided that they shall live. Again, a momentous decision confronts us, the Jewish communities of America. It is asked of us, the people of this free country, to decide whether the remnants of our people in Europe shall continue their miserable existence in the DP camps or whether they shall be liberated and given the chance for a new life in the new state of Israel.Footnote 113

Golden's invocation of collective obligation implies that those who do not fulfill their obligations are guilty of nothing short of murder.

The direct linkage of philanthropy with the saving of Jewish life, as well as overt attempts to create feelings of guilt among potential donors, had been staples of American Jewish philanthropy since the 1920s. The destruction of European Jewry during World War II vastly increased the scale of American Jewish philanthropy, as it did the compassion, grief, and survivor guilt at its emotional core. In 1946 and 1947, the United Jewish Appeal campaigns centered around the resettlement of the DPs. A 1947 brochure, employing the same crude, red, block letters of the 1948 “Jewish Blood Flows Again” pamphlet, urged Jews to “HURRY! Do not measure your giving this year by last year's standard—This year is an emergency!”Footnote 114 The 1947 fundraising film Shadows of Hate presented images of the postwar prosperity of the United States—people buying goods at a department store, cruising down the highway in new automobiles, and eating ice cream at an amusement park—and noted that for Americans, “the war is all but forgotten.” The film then dramatically revisited the events of 1933 to 1945 in Europe, described the plight of the DPs and the role of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee in settling them in Palestine, and ended with a speech by Dwight Eisenhower, the Army Chief of Staff and former Supreme Commander of the Allied forces in Europe, appealing to people of conscience to come to the DPs’ aid.Footnote 115

In the film, Palestine was presented only as a receptacle for Holocaust survivors; there were no depictions of Palestine's Jewish community. A similar identification of the future Jewish state with the survivors came in a 1947 UPA fundraising poster depicting a well-manicured hand emerging from a suited sleeve, handing a trowel to an outstretched, tattooed arm, superimposed upon a map of Palestine (Figure 3).Footnote 116

Figure 3: United Palestine Appeal yearbook cover, 1947. (Source: The Palestine Poster Project Archives, https://www.palestineposterproject.org/poster/night-of-stars-united-palestine-appeal-2.)

The 1948 UJA campaign thus represented a difference in degree, not kind, from the previous two, post-Holocaust, years. The creation of Israel added drama, hope, pride, and urgency to an existing sense of crisis. Rather than emphasize what was new about the situation, however, the campaign largely avoided the ongoing Arab-Israeli war, partly because of the overlapping turfs of the Palestine-oriented and diaspora-oriented philanthropies under the UJA's umbrella, but also because the American Jewish public was not uniformly Zionist and was more likely to respond sympathetically to appeals to assist Holocaust survivors. In April 1948, a series of UJA advertisements in Time magazine urged American Jews to “Be ready, as the gates swing open in DP camps in Europe and Cyprus. In Palestine, we must be ready with food, medicines, clothing, schools, hospitals—everything. And we must be ready in other lands of haven. The destiny of a people is at stake. Whether a nation will live or die depends on your giving.”Footnote 117 Shifting seamlessly between high-flown rhetoric and pragmatic calculation, the advertisements provided a list of twelve donation categories, called “a price list for survival,” ranging from $36.50 to $100,000. All twelve were directed toward refugee resettlement—nine in Palestine and only three in the United States.

In their treatment of donors and beneficiaries alike, the advertisements’ rhetoric switched between passivity and activism, powerlessness and empowerment. By giving generously, American Jews would “lift up our stricken brothers.” If they stand aside, “We make a mockery of our six million dead.” Once settled in Palestine, the survivors will be masters of their own fates. Philanthropy will not render them dependent: “$10,000 will construct two three-room houses, with bathrooms and kitchens, for two families in Palestine. They will build the houses themselves, build the new nation. We must provide the means.”Footnote 118 One cannot prove a causal link between this rhetoric's emotional charge and the fundraising drive's phenomenal success. But the discursive continuity in the fundraising campaigns after 1945 suggests that Jewish activists considered the appeal to compassion for one's fellow Jews, on the one hand, and guilt for living in safety while other Jews suffer or die, on the other, to be a winning strategy.

The UJA's 1948 “Year of Destiny” campaign, launched and run during the first Arab-Israeli war, displayed and intensified emotional bonds linking American Jews and Israel. Both the campaign's strategy and the emotions it appealed to were inseparable from the Holocaust and post-1945 appeals for donations on behalf of surviving European Jews. In American Jewish public discourse, in 1946 and 1947 Palestine was already depicted as the natural destination for the survivors. Given ongoing xenophobia and antisemitism in the United States, it was imprudent and unrealistic to call for substantial refugee resettlement within the country. The events of the 1948 war, however, produced an emotional dynamic of their own, with heightened feelings of concern for, and pride in, the new Jewish state.

A fertile combination of top-down and grassroots forces created America's community of Zionist sympathizers. On the one hand, scores of journalists, rabbis, and Jewish activists, hundreds if not thousands of miles apart and beholden to no single authority structure, expressed similar feelings about Israel. Although the most prominent American Zionist leader of the time, Abba Hillel Silver, was highly visible in the American Jewish press, his views played no visible role in the creation of the emotional rhetoric examined in this article. On many issues involving the course and consequences of the war, direction from Israeli leaders such as Golda Meyerson, Moshe Sharett, Chaim Weizmann, and Abba Eban informed American-Jewish opinion, and Meyerson's ability to both empathize with and inspire an American audience was sans pareil. Yet although voices from Palestine provided a convincing and appealing narrative of events on the ground, the Israeli leaders, like the UJA campaign itself, had to accommodate the primacy of American Jewish emotional connections with Europe and Holocaust survivors over Israel and the country's existing population. Moreover, despite similarities in emotional expression, each American Jewish community featured distinct qualities, such as the historic prevalence of a non-Zionist Reform Judaism in San Francisco.

The story of American Jewry in 1948 throws new light on the formation of emotional norms among nonstate communities. Existing scholarship explicates the construction of what the sociologist Arlie Russel Hochschild called “feeling rules” within states, broad sectors of civil society, and social movements.Footnote 119 Feeling rules, however, can also be constructed among members of minorities who feel bonds to a transnational community defined by ethnicity, creed, or both. As Jaclyn Granick has noted, “Forms of humanitarianism in history were a primary political tool of diaspora and non-state transnational politics.”Footnote 120 In the immediate postwar era, the activity of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee in Europe and the United Jewish Appeal on behalf of the creation of a Jewish state as a refuge for European Jewry in some ways paralleled that of American organizations like Lutheran World Relief (most of whose funds targeted Germany) and Catholic Relief Services. CARE, founded in 1945, allowed donors to designate the beneficiaries of food packages, thereby bonding ethno-religious communities in America with kinsfolk abroad. Smaller agencies, mobilized largely along ethnic lines, provided relief funds to Poland, Greece, Yugoslavia, and many other European countries.Footnote 121 As Michael Barnett has observed, “It was always easier to feel compassion and raise money for those who were part of the family.”Footnote 122

The parallels between Jewish and other forms of minority-group humanitarianism, however, have limits. American Jews were engaged in not merely relief efforts but also state creation. Their situation was closer to that of Irish-Americans assisting the Irish struggle for independence between the Easter Rising in 1916 and the end of the Irish Civil War in 1923.Footnote 123 Whereas CARE and Catholic Relief Services received substantial funding from the United States government, the Irish-American and Jewish-American philanthropies were left to their own devices. In both cases, the emotional charge of a mobilized ethno-religious community both responded to and shaped the political, social, and economic milieu in which the community operated.

For residents of a state beset by conflict, nationalistic feelings of love of country, combined with fear for both that country's existence and one's personal safety, are often the most dominant emotions. But the feelings of compassion, pride, and guilt that form the core of this article assume a sense of both commonality and foreignness, proximity and distance, between members of an ethnic minority and their putative homeland. Unlike empathy, which involves an internalization of the feelings of others, compassion can involve acknowledgment of another's suffering while not suffering oneself. It was precisely Israel's distinctiveness from diaspora Jewish self-images—its embodiment of pioneering values and military valor—that made it such a source of pride. And the guilt felt by American Jews toward their European brethren presupposed the chasm that divided the two communities—the one that flourished and the one that was destroyed.

Material comfort and physical security among American Jews did not eliminate a deep-seated anxiety, rooted in historical memory, sustained by encounters with antisemitism in the United States, and intensified by the Holocaust. Widespread public support for Israel's creation granted legitimacy to a longstanding American Zionist discourse of a Jewish national home as an outpost of American democracy. This rhetoric deflected accusations of dual loyalty and facilitated unfettered solidarity with the state of Israel over the course of the 1948 war.

The emotional palette of American Zionism was a product of the immediate post-Holocaust era in the United States. In the years following Israel's establishment, an enthusiastic and passionate love for the young state emerged alongside of, and eventually surpassed, anguish and guilt over the Holocaust and compassion for persecuted Jews abroad as the most prominent emotions expressed in American Jewish public rhetoric. Avowals of love for Israel scarcely appeared in the Jewish press and fundraising literature in 1948, but they became more common thereafter. The romantic image of Israel propagated by Leon Uris's 1958 best-selling novel Exodus (and the popular 1960 film) had an enduring resonance among the Jewish public. Israel's dramatic victory in the 1967 War accelerated Israel's transition to become the cornerstone of American Jewish identity, in which the traditional rabbinic concept of ahavat yisra'el—love of the Jewish people—melded with nationalistic love of the state of Israel.Footnote 124 In 1948, in contrast, when the Jewish state was just coming into existence, it was not an object of love so much as passionate solidarity.