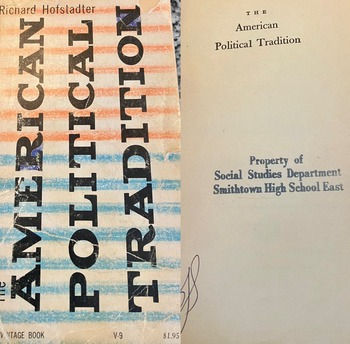

The year 2023 marked the seventy-fifth anniversary of the publication of Richard Hofstadter's The American Political Tradition: And the Men Who Made It—a bestselling book that captured the imagination of many of Hofstadter's fellow Americans in the early postwar period and, at the same time, defined the terms of argument for much of academic history for the next generation.Footnote 1 It was also the book my high school teacher, Mr. Backfish, assigned in eleventh-grade Advanced Placement (AP) American History that helped transform me into a historian. So different was it from the dry, conventional textbook in both its riveting, sometimes acerbic prose and its unsentimental view of venerated figures in the American past. I still have my original copy (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Author's copy of The American Political Tradition by Richard Hofstadter, once the property of Smithtown High School East.

If that were not reason enough to reflect on Hofstadter's conception of enduring political traditions, for years I have asked students during their PhD oral examinations to imagine a sequel to Hofstadter's book that extended The American Political Tradition into the post–World War II era and followed the original in choosing individuals or small groups to embody the defining features of American politics. When Historians of the Twentieth Century United States (HOTCUS) kindly asked me to deliver this year's keynote, it seemed that bill had come due: that I owed those students—and you—something like my own answer to that question.

But first, some background: in 1948, Columbia University professor Richard Hofstadter published a landmark in American historical writing: The American Political Tradition and the Men Who Made It (Alfred A. Knopf). In a dozen tightly connected essays, Hofstadter profiled the Americans—the presidents, protesters, and political hacks—who defined the nation's distinctive political legacy. Shaped by the social criticism of the 1930s, Hofstadter (born in 1916) had come of age during the Great Depression. The book, he later explained, viewed American politics from “a vantage point well to the left, and from the personal perspective of a young man who has only a limited capacity for identifying with those who exercise power.”Footnote 2

The young historian kept two targets in his sights. First, Hofstadter explicitly punctured what he called the “national nostalgia.” Exposing the heroic figures of the nation's past to unsentimental, unvarnished analysis, Hofstadter took down the framers of the Constitution, Andrew Jackson, Abraham Lincoln, and both Roosevelts, while expressing grudging respect only for outsiders like the abolitionist Wendell Phillips and the slaveocrat John C. Calhoun (whom Hofstadter memorably nicknamed “the Marx of the Master Class”). A democratic society, he asserted, could “more safely be overcritical than overindulgent in its attitude toward public leadership.”Footnote 3

If Hofstadter aimed first at the nostalgia of general readers, he also targeted the prevailing view of his fellow professional historians that conflict, especially conflict between “the people” and “the interests,” defined U.S. history. Instead, Hofstadter identified the “central faith” at the heart of the national political tradition as a fundamental consensus around property rights, economic individualism, and the prerogatives of private enterprise. American politics produced much smoke, but little fire: “The fierceness of political struggles,” Hofstadter warned, “has often been misleading; for the range of vision embraced by the primary contestants … has always been bounded by the horizons of property and enterprise.” While he conceded that ideas hostile to the fundamental working arrangements of modern industrial capitalism have appeared, they were “confined to small groups of dissenters and alienated individuals.”Footnote 4

The American Political Tradition ended with Franklin D. Roosevelt. Over the ensuing seventy-five years, American politics has morphed so violently that Hofstadter would hardly recognize it. Among the developments he could not have foreseen in 1948 (many of which would have still seemed remarkable upon his untimely death in 1970) would be the rise of the political right, the ideological sorting of the two major parties, and the potency of extra-party political organizations, most conspicuously in the Civil Rights Movement and its heirs, but also in consumer and environmental politics, and the rise of media politics.

Taken together with a wider-angled lens that embraces not only women as well as men (not the “men who made it,” but the “people”), but also many Americans long excluded from electoral politics, these transformations call into question the whole idea of coherent American political traditions. The concept seems not only to flatten out historical time, finding commonalities among figures occupying dramatically different historical circumstances, but also to minimize resistance and protest, to make dissent a colorful distraction rather than a fundamental feature of American politics.

Certainly, historians of the 1960s, anxious to excavate a usable past for their own social movements, levelled these charges at The American Political Tradition and often lumped Hofstadter together with other so-called consensus historians, who they saw as ironing out the complexity and multiplicity of the American past in service of the Cold War state.Footnote 5 Writing in Commentary magazine in 1959, John Higham, a prominent scholar of ethnicity and immigration, lamented the passing of a generation of historians “nurtured in a restless atmosphere of reform” that “had painted America in the bold hues of conflict.” Hofstadter and his fellow architects of what Higham denounced as the “cult” of the American consensus instead depicted the United States as “a happy land adventurous in manner but conservative in substance, and—above all—remarkably homogenous.”Footnote 6 A decade later, historian Barton Bernstein assembled an anthology of New Left scholarship. Billed as an “anti-textbook,” Towards a New Past attacked Hofstadter's “narrow framework.” The volume's “dissenting essays” rejected the idea of an enduring American political tradition “in which even the dissenters usually accepted the fundamental tenets of the liberal tradition.”Footnote 7

New Left scholars exposed the self-congratulatory myopia of some consensus history and surfaced previously submerged historical voices. Still, I see usefulness in the concept of political traditions. Why? First, it acknowledges and accentuates continuities. In a culture that prizes novelty and a historical profession that, for all its formal obeisance to both continuity and change, clearly privileges the latter (every time historians choose starting and finishing dates for their books, they make a case for discontinuity)—the concept of a tradition highlights persistent, enduring features of public life.

Second, political traditions also underline the importance of what historian Michael McGerr called “political style.”Footnote 8 That idea sounds trivial, a trifling counterpart to substance. But if substance involves ideological debates and the shaping, implementation, and consequences of public policy, style refers to the diverse ways that Americans entered and interacted with the political arena: how they conceived of, spoke about, organized, and acted politically. It matters that some Americans participated in politics at party headquarters, ballot boxes, and torchlight parades; others formed voluntary associations or founded settlement houses or sat in at lunch counters; some published pamphlets and others watched television.Footnote 9

Having dispensed with the preliminaries, three main traditions have structured American political life since World War II. Significantly, these traditions embraced, defined, and structured the political activities of all sorts of Americans (not just professional politicians and government officials, not just white males), and their boundaries, while distinct, remained permeable. Not only do historical figures cross borders over time (Jesse Jackson, for example, moved from the social movement tradition into the liberal machine tradition), but the traditions have been fundamentally interactive—shaping and shaped by each other.

How would I classify them? First, the liberal machine tradition. Emerging out of and sharing key features with the urban political machines of the late nineteenth century, this mode of politics—transactional, top-down, believing in and often relying on charismatic leadership—metamorphosed after World War II into modern American liberalism. Committed to the concrete potential of electoral politics—that winning elections and taking power over the government allowed political actors to deliver tangible goods and services to constituents—the liberal machine tradition insisted that government could and should do good things for people. This tradition developed in the nineteenth century out of the hurly-burly of antebellum party politics, evolved into the political machines of the late nineteenth century, and in the twentieth century found its mature form in the state-based liberal activism of FDR and the New Deal.

In the postwar era, nobody embodied this tradition more fully than Lyndon B. Johnson. “Now of course you have to understand,” his vice president, Hubert Humphrey, explained, “above all he was a man steeped in politics. Politics was not an avocation with him. It was it. It was the vocation…. It was his religion…. Every time you saw him it wasn't like seeing a man; it was like seeing an institution, a whole system that just encompassed you.”Footnote 10

The person and the tradition fused in that passion for politics, and a vision of political office as a platform for constructive action. “Some men want power simply to strut around the world and hear the tune of ‘Hail to the Chief,’” LBJ told Doris Kearns after his retirement from the White House. “Others want it simply to build prestige, to collect antiques, and to buy pretty things. Well, I wanted power to give things to people, all sorts of things to all sorts of people.”Footnote 11 Johnson and his fellow liberals harbored few doubts that government could and should improve American life. They had little sense of the limits of government action—the unintended, self-defeating consequences of some well-intentioned policies.

They also had little understanding of and less patience for other forms of political action. Exponents of the liberal machine tradition, such as Johnson and Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley, measured achievement in terms of “getting things done”: plowing the snow, collecting the trash, building bridges. Taking pride in the city's efficient provision of those services, Daley proclaimed Chicago “the city that worked.” Postwar liberal machine politicians remained focused on the local and practical, trading tangible assets like votes, dollars, and jobs. Bargaining oiled the machine. Defeats were defeats; there was no such thing as a symbolic victory or a principle beyond compromise.Footnote 12 Johnson, for example, distrusted, even despised, crusading leaders and unwavering attachment to principle; he rarely, if ever, felt torn between principle and expediency. Effectiveness was his basic principle, the cornerstone of his brand of liberalism. Recalling the fate of a Texas colleague who lost re-election, Johnson frequently reminded aides that “there's nothing more useless than a dead liberal.”Footnote 13

In December 1965, Daley phoned the president with holiday greetings and learned that a group of antipoverty activists from upstate New York had protested outside LBJ's Texas ranch. “They're trying to snatch control of this country, control of everything just under this program,” Daley warned Johnson. “And the fact is, and the truth of the matter is, that they've never had such a fine program in the history of our country.” Daley rejected the protestors’ concerns about empowerment—who will participate in and oversee government programs. “What difference does it make who will get the credit,” the mayor asked, “as long as we get jobs, and get the people out of slums and blight, and get education?” But “many of these people throughout the country are not concerned with the solutions,” Daley lamented. “They're concerned with the agitation of the problem.”Footnote 14

Distilling the essence of the liberal machine tradition in 1967, Robert Lekachman explained that “a viable political consensus rests upon an expectation of benefits by all members of the coalition.” Some might benefit more than others, the prominent economist conceded, “but in spite of their inevitable inequities, consensual arrangements often persist, since those whose share is scantiest either assent to the larger share of others, feel powerless to improve their relative situation, or sense that any alternative feasible political commitment would be still less advantageous.”Footnote 15 In Johnson's and Daley's minds, the antipoverty activists demonstrating outside the president's door engaged in purely symbolic action. The protesters’ demands for recognition and decision-making authority meant they really did not care about practical solutions.

Those demonstrators emerged from a different stream of American political history: the social movement tradition. Hofstadter identified this thread seventy-five years ago in his study of the abolitionist Wendell Phillips. In The American Political Tradition, Hofstadter differentiated the politician—guided by success, trapped in the present, subordinating the right to expediency—from the activist, motivated by “a reasoned philosophy of agitation,” whose function was not to “make laws or determine policy,” but to “influence the public mind in the interest of some large social transformation.”Footnote 16 Addressing a Massachusetts audience in 1852, for example, Phillips pledged “to extract from the reluctant lips of the Secretary of State” testimony to “the real power of the masses.”Footnote 17 According to Phillips, every government official necessarily became, in his words, “an enemy of the people.” By joining government, they “gravitate against that popular agitation which is the life of a republic.”Footnote 18

Flourishing especially but not exclusively among those excluded from party politics (in particular, women who developed and sustained an alternate universe of political organizations, tactics, and ideas), the social movement tradition practiced a bottom-up style of activism. Often suspicious of charismatic leadership and at best ambivalent about electoral politics, social movements could voice not only programmatic claims—demands for specific actions or policies—but also claims of identity (that their members constitute a political force) and of standing (that they deserve rights, influence, and social goods).

To adapt sociologist Charles Tilly's influential formulation, social movements constitute a distinctive form of contentious politics that developed in the late eighteenth century. They consist of “a sustained, organized public effort making collective claims” that employ a variable ensemble of tactics that Tilly calls the “social movement repertoire,” which include the formation of special purpose associations and coalitions, public meetings, vigils, rallies, demonstrations, petition drives, and pamphleteering. Participants also make concerted public representation of their worthiness, unity, and commitment. Finally, social movements assert popular sovereignty. They need not be democratic (social movements differ on how they define “the people” and who they include among them), but they stress the consent and participation of the governed and often challenge the legitimacy of representative government.Footnote 19

In the United States, the struggle for civil rights constituted the definitive social movement of the post-WWII era: definitive not only in its impact on American life, and in innovating the repertoire of social movement strategies, but also definitive in reshaping the nature and understanding of a social movement.Footnote 20 At once central to and emblematic of this redefinition of the social movement tradition was Ella Baker. Born in Norfolk, Virginia, in 1903, Baker grew up in Jim Crow North Carolina and attended Shaw University, the historically Black college in Raleigh, before launching a career as civil rights activist, organizer, and strategist, working at different times and places with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). SNCC activist Mary King described Baker as “the pivot, as the catalyst for many civil rights organizations.”Footnote 21

In the postwar era, asserting and communicating the political nature of lived experience became central to social movement politics. Grassroots mobilization depended on making connections to the daily lives of individuals, families, and local communities. “Maybe you would start with some simple thing like the fact that they had no street lights,” Baker explained in a 1970 interview with activist-historian Gerda Lerner, “or the fact that in the given area somebody had been arrested or had been jailed in a manner that was considered illegal and unfair, and the like. You would deal with whatever the local problem was, and on the basis of the needs of the people you would try to organize them….”Footnote 22

In developing that strategy, Baker and her collaborators, especially during her work with SNCC in the early 1960s, made explicit and essential a persistent tension in the social movement tradition between sustainers (local actors who defy settled practice and keep up the pressure for change, often forcing the power structure to seek negotiating partners) and brokers (who translate the struggle into terms that can be negotiated with that power structure). As a woman who worked largely behind-the-scenes and who understood, in her words, that because “it was sort of second nature to women to play a supportive role,” Black women largely carried the movement, Baker not only emphasized sustainers—the local, emergent grassroots activists—but developed an explicit critique of charismatic leadership. “I have always felt it was a handicap for oppressed peoples to depend so largely upon a leader,” Baker explained, “because unfortunately in our culture, the charismatic leader usually becomes a leader because he has found a spot in the public limelight. It usually means he has been touted through the public media, which means that the media made him, and the media may undo him.” Because such leaders won acclaim from the establishment, there also developed the danger that “such a person gets to the point of believing that he is the movement. Such people get so involved with playing the game of being important that they exhaust themselves and their time, and they don't do the work of actually organizing people.”Footnote 23

Reliance on brokers not only diluted the force of a social movement, it undermined its most basic task: highlighting the necessity of individual commitment, the worthiness and potency of grassroots action. “The major job,” Baker argued, “was getting people to understand that they had something within their power that they could use, and it could only be used if they understood what was happening and how group action could counter violence even when it was perpetrated by the police or, in some instances, the state….” Her fundamental goal, she explained “has always been to get people to understand that in the long run they themselves are the only protection they have against violence or injustice.”Footnote 24

This antipathy to conventional forms of leadership has remained a defining tension within American social movements and informs contemporary debates about the differences between grassroots action and so-called “Astro-turfing,” or the propagation of fake grassroots campaigns orchestrated and funded by elites.

After the social movement tradition and the liberal machine tradition, a third component of American political life, every bit as enduring and influential as the others, is the Mugwump tradition. Neither top-down, nor bottom-up, the Mugwump tradition operates from the middle ground. Endeavoring to check and channel both electoral politics and social movements, Mugwumps stress process over particular policy outcomes and elevate a particular conception of the public good or the general welfare. The Mugwump tradition imagines “the public” as an entity—different from interest groups, parties, and social movements—and imagines a model of public service that is disinterested, ideologically neutral, and selfless. Associated with upper-class norms and ideals of noblesse oblige and Christian service in the nineteenth century (think Theodore Roosevelt, Sr., father of the president), Mugwumps increasingly embodied and emphasized professional standards in the twentieth century—their training, methods, and ethics as physicians, academics, businessmen, and, most important, lawyers. While often personally moralistic, Mugwumps offered structural diagnoses of the problems of American democracy and prescribed structural remedies. It was not enough to get “good men” into politics; the premise of Mugwump politics posited that the system defied the ministrations of good men. A 1908 advocate of replacing Des Moines, Iowa's mayor and council with a city commission encapsulated this sentiment: “Fiddlesticks, you may say. Good men can accomplish these things under any system. But they can't. Good men have tried here and elsewhere. Something has always been wrong with the system.”Footnote 25

The Mugwump tradition took institutional form in early twentieth-century municipal government and, prominently, in the tripartite commissions of the first and second world wars that divided authority among representatives of labor, management, and “the public.” The World War I War Industries Board and War Labor Board included representatives of business, unions, prominent attorneys, representatives of the armed forces, and former government officials like retired President William Howard Taft. Codifying the tripartite structure during World War II, the four original “public members” of the latter National War Labor Board included a lawyer, William H. Davis; two academics, University of North Carolina President Frank P. Graham and University of Pennsylvania economist George W. Taylor; and a legal academic, University of Oregon Law School Dean Wayne K. Morse.Footnote 26 When those men rotated out, other lawyers and academics replaced them.

In his classic book, Hofstadter all but ignored this Mugwump branch of the family tree of American politics, mocking these reformers as “isolated and sterile” and favorably quoting party regulars who denounced them as effeminate. Not only did the Mugwumps lack mass appeal, Hofstadter asserted, but their insistence on a public good separate from simply maximizing private gain rowed against the current of American politics. Whether intellectuals motivated by the “abstract ideal of public service,” businessmen seeking a more efficient public sphere, or patricians horrified by the influence of the riffraff on civic affairs, nineteenth-century reformers, in Hofstadter's view, neither understood nor seriously engaged with the genuine problems of an industrializing society.Footnote 27 Still guided by his youthful leftism, Hofstadter regarded the reformers’ focus on ethics and process as nostalgic—a backward-seeking inability to grasp the realities of economic power in a modernizing nation.

In that portrait, Hofstadter could not have been more wrong. “Mugwumpery” flourished in the post–World War II period, undergirding the rise of a new public interest sector in American politics—a massive infrastructure of nongovernmental organizations and public interest law firms. The son of small-town Lebanese immigrant restaurateurs in northwestern Connecticut, Ralph Nader embodied and energized this tradition. Educated at Princeton University and Harvard University's Law School, Nader became a national figure with the 1965 publication of his bestselling attack on the automobile industry, Unsafe at Any Speed.

In a 1972 appearance on the Dick Cavett show, Nader explained his commitment to the science of citizenship. Americans needed to “to organize in a non-bureaucratic, non-institutional way” to develop “what might be called a citizenship lifestyle.” Enjoying “increasingly a lot of leisure time, typically for white collar workers,” he recommended that Americans “begin looking at citizenship which is in effect defining problems that people can do something about, developing solutions, as a science….” Nader welcomed the participation of ordinary Americans, who ought to devote time to developing their skills as citizens, but he also envisioned and advocated a cohort of professional citizens: “We're going to support some people working full time as professional citizens representing community groups or statewide student groups and begin to develop the science of citizenship.”Footnote 28

Launching an intellectual and legal attack on the post-WWII administrative state, Nader and the broader public interest movement he helped to form in the 1960s and 1970s pioneered new strategies of political action like citizen lawsuits and created an alternative establishment made up by public interest law forms, liberal foundations, and nonprofit advocacy groups. Informed by New Left critiques of the corrupting influence of institutional power, public interest activists founded, in historian Paul Sabin's terms, “a proliferating array of small, independent, issue-based nonprofit organizations” that developed both an ideological critique of the insulated, unaccountable power of government bureaucrats and the institutional tools to challenge their autonomy—a very different repertoire and a very different relationship to power than social movement activists.Footnote 29

Building a multifaceted nonprofit sector into potent political force, Nader and allies like Common Cause founder John W. Gardner and Carnegie Foundation officer Eli Evans invented new kinds of law firms and advocacy groups; pioneered lobbying, legal, and public relations strategies; and blazed new career paths outside government for highly educated, socially conscious, young people. Recognizing that they could not rely sustainably on the foundation grants that had initially supported them, they developed novel funding streams: dues-paying members, government grants, and revenues from fee-shifting rules that allowed public interest firms to recover revenues from the defendants they sued.Footnote 30Emulating these Mugwump institutions, during the 1970s conservative lawyers and businesspeople established their own nonprofit legal foundations around the United States.Footnote 31

Yet, while “Nader's Raiders” may have invented a new type of law firm, the struggle between law and administration, between bureaucratic autonomy and litigation as engine of public policy, had defined American politics since the early twentieth century. In pervasive and distinctive ways, law formed the functional vocabulary of governance in the United States; legal procedures, courtroom proceedings, and lawyers both expanded and constrained the scope of government action, even at the height of the administrative state. With lawsuits as its chosen weapon, and “sue the bastards” as its rallying cry, the public interest movement carried on a long Mugwump tradition stretching back to the efforts of civil service reformers who demanded statutory specificity to rein in political corruption.

In fact, while recent accounts like Sabin's book portray the public interest movement as novel and radical, featuring protagonists like the second-generation immigrant Nader and anti-establishment thinkers like Rachel Carson and Jane Jacobs, the public citizens of the 1960s and 1970s remained as much creatures of the Establishment as their nineteenth-century Mugwump forbears. Graduates of elite law schools almost exclusively staffed public interest law firms (Nader recruited most of his Raiders from the Ivy League); nonprofits attracted funding from prominent foundations like Carnegie and Ford, where executives like McGeorge Bundy made sure they conformed to elite, Mugwump notions of disinterestedness. Public interest advocates criticized organized labor and largely ignored the concerns of civil rights activists. In many ways, the efforts of public interest advocates to organize a “constituency for good government” and restrain the power of corporations recall the “goo-goos” of the late nineteenth century and Progressive Era critics of monster trusts.

Of course, the major criticism of and the most formidable constraint on Mugwump politics had been its elitism—its inability to excite popular support. That had animated Hofstadter's disdain in 1948 as well as the mockery of machine politicians from Plunkitt of Tammany Hall to Mayor Daley. Neither seeking partisan spoils nor advancing claims for inclusion or social justice, Mugwumps seemed out of touch with the hurly-burly of democratic society. A science of citizenship did not arouse popular passions.

Or did it? In 1970, attempting to disprove that enduring criticism, John Gardner founded Common Cause. Dedicated to the Mugwump ideal of a general, public welfare free from partisan agendas and special interests, and to procedural reforms like campaign spending limitations, Common Cause imagined a Mugwump mass mobilization. Now, on the surface, Gardner hardly seemed a likely candidate to lead that effort. A consummate insider with experience in the foundation world who had worked in the Johnson White House, Gardner had been an important architect of the Great Society, and even served briefly as LBJ's Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare. After leaving Washington, he turned turn down New York Republican Governor Nelson Rockefeller's offer to appoint him to fill Robert Kennedy's Senate seat and, a few months later, rebuffed feelers from the Nixon campaign about joining the ticket as vice presidential nominee.Footnote 32

Instead, Gardner acted on his belief that, much as “the public” needed representation on wartime agencies, “the public” now had to organize to combat special interests. “I realized there was a constituency out there of people who really wanted to solve the problems of the country and were capable of rising above special interests,” he explained shortly after Common Cause's creation. Although many “wise heads in Washington” told him that “those folks aren't out there”—that “everyone had special interests and there could be no common cause,” they “were astonished when in 23 weeks we got 100,000 members.” Gardner was equally flabbergasted.Footnote 33

While the public interest movement never became a mass phenomenon, it continued to influence electoral politics and exercise policy impact; indeed, many important advances in environmental regulation and consumer protection arose from citizen and class action lawsuits brought by Gardner, Nader, and their allies.

Mugwumps, social movements, the liberal machine tradition: I hope that this overview has raised questions about other potential American political traditions and inspired Hofstadter-esque chapter titles like: Jimmy Carter: “The Engineer as Moralist,” James Baker: “The Operative as Revolutionary,” and Barack Obama: “The Activist as Conservator.”

Surely, too, this reflection has prompted a series of “what about” questions. For example, what about populism? Despite the frequent use of the term “populist” to characterize figures from William Jennings Bryan to Donald Trump, populism simply does not represent an autonomous, enduring political tradition. A catchall term, it sometimes describes social movement activists (such as many associated with the agrarian revolt and the People's Party of the 1890s), sometimes machine politicians like Huey Long and Sam Rayburn, sometimes Mugwumps like H. Ross Perot (not to mention a wide variety of authoritarian strongmen across the globe).Footnote 34 “Populism,” one of its leading analysts, historian Michael Kazin, recently conceded in these pages, is “primarily a powerful way of talking about politics—‘the people’ vs. ‘the Elite’ (with multiple variations of how to define those terms). As such, figures on both left and right have used populism to their advantage and will continue to do so.”Footnote 35

While the machine, movement, and Mugwump traditions form enduring modes of political engagement in the United States—ways that Americans from a wide variety of demographic backgrounds and ideological persuasions have engaged in political action, the boundaries between them have remained permeable. These rival traditions persisted in large part because they interacted. Social movements, as Hofstadter noted with regard to Wendell Phillips, have agitated for action by mainstream politicians and shaped the direction of public policy. Liberal machine politics leveraged, or co-opted, or repressed social movement activity. Mugwumps rewrote the rules of American politics and developed new tools of governance that constrained partisans and empowered lawyers. Frequently, activists and reformers, even those formally excluded from the political system, even those suspicious of or hostile to electoral politics, found themselves drawn into the fray: the electoral temptation has been—and remains—a defining feature of the American political tradition.

What lessons, finally, might scholars of modern American history gain from a consideration of American political traditions? When Richard Hofstadter published his classic work in 1948, he had several purposes. First and foremost, he wanted to puncture what he called the national nostalgia—to undermine the heroic version of the American past that he thought dominated the national consciousness. In today's critical, if not outright cynical age, that task hardly seems necessary.

Second, and more important, Hofstadter sought to identify enduring features of the American past—widely shared, highly potent, often unacknowledged ideas, practices, and commitments that persisted over decades and even centuries, that shaped and delimited the short-term conflicts that grabbed headlines and occupied the attention of historians. In this attempt to continue and update Hofstadter's approach, I have played somewhat fast and loose with his methods. But in invoking and trying to develop the concept of political traditions, I have tried to provoke consideration of—and show appreciation for—the enduring, stubborn features of the American experience; to surface the fundamental rhythms, the background radiation, if you will, humming behind the myriad conflicts and paradoxes of American life.