This is the first in a series of Q&A installments intended to bring public history more deliberately into Modern American History. To evaluate the opportunities and challenges the national museums of the Smithsonian face, Teasel Muir-Harmony and Sarah B. Snyder posed a set of questions to historians at several of these institutions: Anthea Hartig (National Museum of American History), Samir Meghelli (Anacostia Community Museum), Michael Neufeld (Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum), Tey Marianna Nunn (Smithsonian American Women's History Museum), and Damion L. Thomas (National Museum of African American History and Culture). Here they share their reflections on the Smithsonian's role in shaping historical narratives, how Smithsonian curators preserve the history of the present, the proliferation of new museums, and other issues.

What is the biggest lacuna of the public's understanding of American history that should be addressed?

Tey Marianna Nunn: For me, the biggest lacuna for institutions to message to the public is to embrace the notion that everyday stories are equally important as the histories of the heroes, the firsts, etc. Often individuals are credited when the idea may have come from a group of people or simultaneously in another place. American history tends to feel more comfortable celebrating individuals rather than examining the environments and communities in which the history is created. I love to discover the untold stories. Regarding women's history, these stories often take more effort to recover and amplify. This usually is a result of who originally told or recorded the stories. The stories are out there, it takes original and primary research to find them.

Samir Meghelli: As a community museum that is part of a national museum complex, our research and community collaboration have continually demonstrated the extent to which national narratives about American history are often lacking in the kind of rich, local detail that can help illuminate how history is actually made—and by extension, how each of us can contribute to making meaningful change in our communities, society, etc.

An unintended and grave consequence of the overly nationally focused curatorial approach, which is often undertaken at the expense of local histories, is that it can seriously distance the museum visitor from the immediacy, urgency, and relevance of that history to their own experience. It may leave the visitor with the sense that history happens somewhere “out there” or “up there”—that is, distant from the local, everyday realities of most Americans—rather than where a great deal of history is made: in people's homes and neighborhoods, in study groups and on streetcorners, at city council meetings, state legislatures, parent-teacher association (PTA) meetings, municipal and state elections, and in district and circuit courtrooms.

In that sense, one of the biggest lacuna of the public's understanding of American history may be just how deeply local our nation's history stretches—or rather, how deeply locally it is rooted. Only through the actions of local historical actors was, for instance, major federal policy made tangible and real for many communities; and vice versa: local historical actors were often major (re)shapers of federal policy. Being able to make those kinds of connections between the local and national clear and meaningful for the broader public is a tremendous challenge, but one that is necessary to address head on in order to help make for a more informed public—and arguably, for a stronger democracy.

Anthea Hartig: Picking just one is challenging, for as James Baldwin famously claimed in a 1963 address to teachers, “American history is longer, larger, more various, more beautiful, and more terrible than anything anyone has ever said about it.” Denial of class divides, systemic racism and pervasive misogyny, and others come quickly to mind. But given that we are lurching towards the semiquincentennial of the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 2026, let's focus on the gaps surrounding that document. Surely, the U.S. has inspired the world with ideals expressed therein; however, to fully understand the nation—its failures and its potential, what pulls us apart and what holds us together—we need to ask revolutionary questions inspired by the Declaration to discuss the restless and uneven pursuit of these ideals.

Truths that historians claimed generations ago—think Edmund Morgan's American Slavery, American Freedom, published in 1975—such as the horrific type of chattel slavery that became the legacy of the nation's founding, the great American paradox that democracy was founded on the backs of African and as well as Indian slavery and genocide, are being re-litigated (see Figure 1). So on the road to 2026, we at the National Museum of American History (NMAH) start with the premise that the Declaration is alive—that its history reaches back before 1776 and extends forward to today. It invites the challenging of assumptions—including those embedded in the Declaration itself, a reaching for ideals and above all questioning. Moreover, democracy is not a settled decision but an ongoing challenge that depends on engagement and action to sustain itself.

Figure 1. The Gunboat Philadelphia, b. 1776, NMAH Collection, R. Strauss, photographer.

Damion L. Thomas: The biggest gap in the public's understanding of American history is how profoundly race has shaped all aspects of American life, including housing, foreign policy, infrastructure planning, emergency relief management, cultural production, and voting rights. Rather than being a subject that is tangential to political, social, economic, and cultural power, it sits at the heart of many of the decisions that impact these areas. In particular, African American history is not a subset of American history, but rather an interpretive lens through which nearly all of American history can be told, understood, and taught.

Michael Neufeld: Given the legislation that has been passed in various states inhibiting or suppressing the teaching of African American history and systemic racism, this country has a long way to go in processing its history of discrimination. The same could be said of the anti-LGBTQ legislation. I do not write about these subject areas, but they concern me as a citizen.

How do you conceive of the role of the Smithsonian as a national, public institution? To whom do you feel responsible in the stories you choose to tell? And what mission or objectives guide you in those efforts?

Damion L. Thomas: At its best, the Smithsonian should serve as the “Great Convener.” It should welcome all Americans and those interested in the American story to learn, debate, and challenge each other to engage the key questions that animate our understanding of the past and that serve as the rationales for the futures that we are imagining.

It is the responsibility of the Smithsonian to tell their American story. However, rather than providing a synthesis narrative, which often leaves groups and portions of our national history unexplored, uncontextualized, and unacknowledged, the Smithsonian needs to strive to tell stories through multiple lenses.

Tey Marianna Nunn: The Smithsonian Institution is a trusted source, and as such, our visitors expect and deserve thoughtful and thorough interpretation. We are a public institution, and we are responsible to everyone. I am especially interested in making sure that the American Women's History Initiative (AWHI), the program I direct, tells the stories of the women whose stories we don't know yet and that we do so throughout the entire Smithsonian. For me, everyday stories, especially from underrepresented communities, help to tell a fuller narrative. They are vital.

Michael Neufeld: The Smithsonian Institution, as the United States government's national museum system, obviously has a large part to play in educating and entertaining the public—national and international. Our three areas of research-based expertise are science, art history, and history. Clearly, in some fundamental sense we are responsible to the American people as a whole, and their political representatives, but we also have to be responsive to the cutting-edge disciplinary research that stands behind our exhibits and public programs. The public perceives the Institution as a collection of museums, but we are also one of the largest research organizations in the United States. We can't responsibly present exhibitions, public programs, web sites, and media that are not based on sound research, whether by our own curators and scientists, or by others. In most cases, that presents no dilemma or conflict, but in a few areas, notably scientific subjects like human evolution and climate change and American history topics like race, gender, and the military actions of the United States, public presentations of current research can make the general public and politicians uncomfortable.

Samir Meghelli: The 175-year-old Smithsonian Institution is the world's largest museum complex and includes twenty-one museums, the National Zoo, and numerous research centers, all working under the broad mission of “the increase and diffusion of knowledge.” But our specific museum, the Anacostia Community Museum, was founded by the Smithsonian in 1967 out of a desire by the larger institution to more meaningfully engage with local African American communities in Washington, DC, whose histories and cultures had been largely excluded from the museums on the National Mall and who rarely felt welcomed there. Our founding director and education director, John R. Kinard and Zora Martin Felton, are due much credit for their important work—along with the many community members of all ages who participated in the effort—who led the charge of reimagining the role that museums could play in society by laboring to bring into being the nation's first federally funded community museum. Both Kinard and Felton had rich backgrounds as community organizers, and they brought that ethos and that of the emerging Black Power movement to collaborate with the local community to conceive of exhibitions and public programs that could celebrate local and Black history and culture, as well as explore contemporary social issues of concern to the neighborhood. They thereby laid the groundwork for a broader “community museum” movement and helped inspire similar community museums around the country and world.

Today, our mission and vision statements explicitly include a commitment to seeing that “urban communities activate their collective power for a more equitable future,” with a focus on the Greater Washington, DC, area. We aim to be most responsive and accountable to our local communities and work collaboratively with them in choosing the stories we tell and in developing exhibitions. Recent exhibitions have included A Right to the City (2018–2020), which explored the fraught history of urban renewal, gentrification, and the long tradition of visionary neighborhood organizing in Washington, DC.

Anthea Hartig: As a public servant and historian, I feel so at home here at the Smithsonian. We commit daily to the broadest form of education. We use our resources across disciplines to explore the nation's increasingly diverse society and how the disparate experiences of individual groups strengthen the whole. Furthermore, the Smithsonian examines how the arts and science have served and continue to serve as means for people and communities to share values and innovation to help all people experience our shared humanity.

Shortly after I arrived at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History four years ago, we expounded on these institutional goals by adopting a new ten-year Strategic Plan for the Museum, from the ground up, written by our staff with broad consultation, introspection, and research. Our new mission is to empower people to create a more just and compassionate future by exploring, preserving, and sharing the complexity of our past. We have challenged ourselves to become the most accessible, inclusive, relevant, and sustainable public history institution in the country. By 2030, the National Museum of American History will serve an audience that reflects the full demographics of the nation. Uplifting this new bold vision, we strive to embody the utmost of professional standards with meaningful work in public service and public history.

Could you share how your museum has dealt with challenging or controversial stories and artifacts (e.g., the Enola Gay, a sexual assault evidence kit, Emmett Till's casket)? How does the Smithsonian's role as a national institution influence your approach?

Michael Neufeld: I recently retired from the National Air and Space Museum (NASM), which has been extraordinarily successful in attracting national and international visitors. We were for a long time the world's most-visited museum and, just before the pandemic, still ranked in the top three worldwide. The foundation for that popularity is the presentation of aerospace technologies that seem to many the embodiment of human creativity and national achievement (see Figure 2). But as a critic of the museum once put it, NASM is shot through with “the romance of technological progress,” which has made it hard to treat some subjects, particularly the military uses of aircraft and missiles, with full honesty.

Figure 2. 1960s-era photo of Rocket Row at the Arts and Industries Building, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 11-009.

A case in point is the Boeing B-29 Enola Gay, the aircraft that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. An attempt to stage an exhibition on the fiftieth anniversary in 1995 was stopped due to political pressure from veterans’ groups, the media, and politicians. The exhibit, in which I was centrally involved, was a well-meaning but, in hindsight, politically naïve attempt to present the atomic bombing of Japan as historically contingent and debatable, not as the only justified and possible ending to the Pacific War. We attempted to be as even-handed as possible, and responsive to the latest historical scholarship, but the exhibit was canceled. The massive outcry of 1994–1995 traumatized and intimidated the Smithsonian and strengthened the forces of caution and self-censorship in the American museum community.

When we opened our new Stephen F. Udvar-Hazy Center in 2003 outside Washington, we unveiled the fully assembled Enola Gay. But the label next to it was and is, like almost every other label there, it only has the most basic information. The airplane deserves a comprehensive and balanced contextualization, but I see no prospect that such an exhibit will be politically feasible any time soon.

Anthea Hartig: The National Air and Space Museum and the Smithsonian's Enola Gay exhibition controversy taught us much as future generations of public historians working in national museums. We all studied it, and I take seriously the field's creation of the “Standards for Museum Exhibits Dealing with Historical Subjects,” and especially that “attempts to suppress exhibits or to impose an uncritical point of view, however widely shared, are inimical to open and rational discussion…. The public should be able to see that history is a changing process of interpretation and reinterpretation formed through gathering and reviewing evidence, drawing conclusions, and presenting the conclusions in text or exhibit format.”

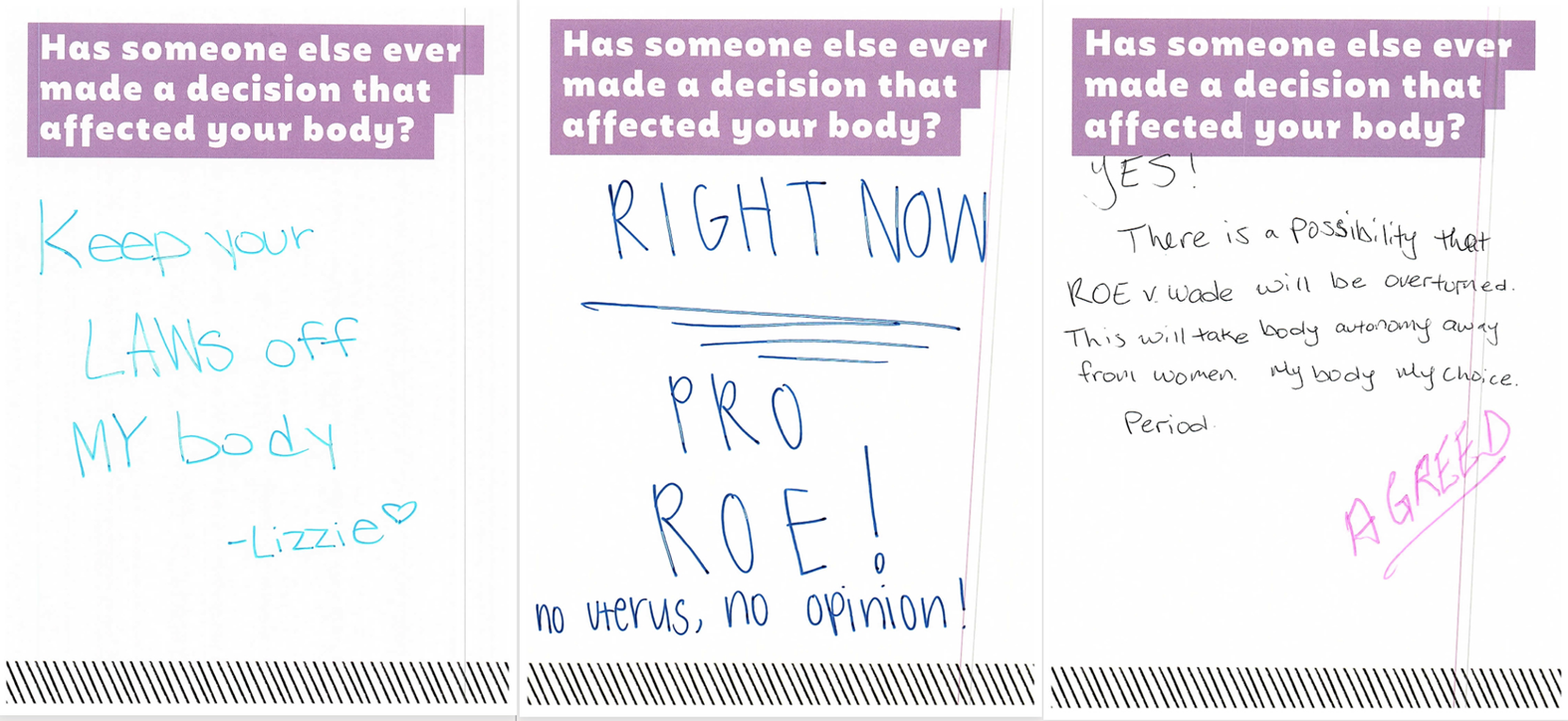

Thus, national museums like ours bear a particular contemporary responsibility for accountability and reckoning with their own histories while at the same time helping people contextualize the present. A recent example is the opening of the exhibition Girlhood (It's Complicated) at the NMAH in the autumn of 2020, after years of research and outreach. Girlhood demonstrated and complicated what it has meant to grow up female in the U.S. It posited the many ways that, in the face of great odds, girls have spoken up and changed the world around them. In the exhibition, we invited visitors to become a part of this long legacy of activism by handwriting notecards for Talk Back boards in the space, each with a different prompt. The museum collected thousands of these cards over two years, but one prompt was especially resonant and powerful: “Has someone else ever made a decision that affected your body?” (See Figure 3.)

Figure 3. Talk Back cards left in the Girlhood (It's Complicated) exhibition, summer of 2022.

After the Supreme Court ruled against Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization on June 24, 2022, and effectively overturned the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision, which held that the Constitution protects access to abortion, visitors voiced their opinions, mostly their outrage, about attacks on reproductive freedom through these Talk Back cards. Our team shared a summary and some poignant examples of those responses in the “O Say Can You See” blog post: https://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/girls-talk-back.

At the NMAH, we are honored to steward one of the historic markers erected by the Emmett Till Memorial Commission in Tallahatchie County, Mississippi, to mark young Emmett's fateful visit there in 1955 (see Figure 4). The Commission donated one of the badly defaced signs that marked the site near where Till's body was found. Working with the community there, we created an exhibition around the sign that has 317 bullet holes and strafes in the very center of the Museum.

Figure 4. River Site historic marker in the exhibit Reckoning with Remembrance: History, Injustice and the Murder of Emmett Till, 2021, NMAH.

We engage our audiences in conversations on various social and political issues. We hope our audience, informed by the nation's long and fraught history, will lead us to a brighter future that centers their needs and their rights.

Damion L. Thomas: It is impossible to engage African American history without wading into controversial issues. It is the Smithsonian's responsibility to ensure that our history is guided by the best and most recent scholarship.

In your question, you reference Emmett Till's casket. My question is, what is controversial about Emmett Till's story or the artifacts used to share his story? Many of the key facts about Till's life are not in dispute: racism factored into his murder, the acquittal of his murderers, and the post-acquittal galvanization of African Americans to fight racial injustice. Perhaps, what is controversial about Till is the way that his story disrupts the traditional telling of American history.

Many people want a version of history that is comforting, erases national wrongdoing, and emphasizes a progress narrative. However, I am guided by the words that President Bush spoke at the opening ceremonies for the National Museum of African American History and Culture in 2016, where he called the museum “a symbol of the country's commitment to truth.” Bush, who signed the legislation authorizing the museum in 2003, reminded us that a “great nation does not hide its history; it faces its flaws, and corrects them.”

Samir Meghelli: Our museum's origins as an “experimental,” “store-front” museum in the late 1960s lent itself to dealing with what some considered “controversial” issues. In fact, when our museum debuted its 1969 exhibition, The Rat: Man's Invited Affliction, it was met with great consternation, largely for the fact that a museum—and a Smithsonian museum, no less—would broach the problem of rat infestation, using it as a window onto broader contemporary issues like urban ecology and social inequality (e.g., why it was that certain neighborhoods—like Anacostia—disproportionately faced rat infestations and also a relative lack of municipal services). But the exhibition grew out of a desire by neighborhood youth to learn more about these animals that they saw and had to deal with in their everyday lives, and from their questions about how and why rats were more concentrated in their neighborhood than others in the nation's capital city. As our then-director John Kinard wrote in 1972, “Museums can no longer be content with defining themselves only by what they have to display—remaining static and unmoving.… More attention must be paid to the interests of greater numbers of people. Controversial issues can no longer be avoided, even if this means taking risks…. History must be brought to life by relating it to life today.” He continued, “It is our responsibility to present the results of our research through every innovative device available and to interpret what we have found to be true no matter how controversial this information may be or what interest groups it may affect.”

In the years since, the museum has remained a kind of incubator and innovator for forward-thinking approaches in community-rooted museum work, even when that has meant exploring issues that some may deem “controversial.” When navigating what might be difficult topics, such as gentrification, food insecurity, and environmental justice (all of which we explored in recent exhibitions), we rely on our deep research (archival, oral historical, etc.), always informed by meaningful collaboration with local residents, and hope to spur conversation—informed conversation—about these challenging but relevant issues. I think that mandate stems from our status as being part of a national institution: helping to provide information and inspiration for spirited dialogue.

Tey Marianna Nunn: The AWHI is now part of the new Smithsonian American Women's History Museum. We are so new that we don't have a physical building yet and won't expect to for some years now. We will start with an innovative “Virtual Museum.” Our mission is to elevate American women's stories and accomplishments and in doing so, we will present expertly researched findings based in fact.

Curators from the Museum of American History have collected artifacts from January 6, including by walking on the National Mall the next day. Smithsonian curators have also been asked to consider what they can collect that records the experience of COVID-19. How do you understand a mandate to preserve the history of the present, especially of politically charged events? Put another way, how is “national significance” determined or evaluated in the present?

Damion L. Thomas: As I think about what I should collect, I always ask myself this question, “What will the curator who will occupy my role in 50 years wish I had collected?” As such, I have a responsibility to collect based upon my understanding of the past, but also with an appreciation that different narratives, questions, and perspectives will influence our future telling of history. While it is impossible to know how the future will look, it is my responsibility to always have the future of this museum in mind when I do my work.

One of the things that the Smithsonian does best is to provide historical contextualization to contemporary questions and issues. While history does not repeat itself, it is important to understand how our contemporary issues have been debated, addressed, legislated, and protested in the past.

Tey Marianna Nunn: We must be inclusive. We cannot tell history from one singular lens. History making is an everyday occurrence. History is a continuum, and we would be doing a great disservice to that continuum if we did not record the present for future interpretation and historic connections.

Michael Neufeld: Many things generated by political campaigns, protests, and crises may be ephemeral and difficult or expensive to collect years later. The American History Museum, and the Smithsonian generally, needs to reflect the whole country, all groups and experiences, including objects that invite controversy and make people uncomfortable.

Of course, any contemporary collecting always reflects the time in which those objects were collected and the values of the curators who collected them. Any determination of “national significance” at any given time is subject to later criticism, based on changing values and emerging scholarship. That applies to all artifacts we collect—later generations of curators will ask why we collected this, but not that. But that should not stop us from collecting in the moment, as otherwise, important and telling artifacts and voices may be difficult to acquire later.

Samir Meghelli: As a community museum, we have a long tradition of what is sometimes referred to as contemporary collecting, rapid-response collecting, or documenting/preserving a history of the present. We have a large collection of documentary photography done by museum staff members over the years of various events, moments, protests, etc. that were deemed as of significance as they were unfolding. And thankfully we do, because those materials have been helpful in trying to reconstruct historical events and in being able to narrate such moments in exhibitions. As early as January 1971, the museum curated an exhibition entitled … Toward Freedom that sought to put the very recent Civil Rights and still-unfolding Black Power movements in historical context, and the museum exhibited the Hunger's Wall from the 1968 Poor People's Campaign at a time when that campaign was widely considered a “failure,” seen as just a muddy nuisance that had overtaken the National Mall.

I think from the vantage point of our work as a continuously locally engaged museum, we try to the best of our ability to remain attuned to current events—with the eye of an historian—to determine when such moments are occurring and to document them through photography, oral history (even as they are happening or have recently happened), and collecting of material culture. In a recent example, there was a group of us curators from several Smithsonian museums who spent time at Lafayette Square/Black Lives Matter Plaza in the summer of 2020 documenting and preserving material from the racial justice protests, including signs, art, and other ephemera (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. Smithsonian curators collecting at Black Lives Matter Plaza, 2020, Smithsonian Institution, Nancy Bercaw photographer.

In short, I don't think there is an easy rubric to determine “national significance” when doing contemporary collecting, but seeing the present through the prism of the past—looking for unprecedented events, or significant events/moments that fit squarely within longstanding social, political, or cultural traditions—helps to train the eye to perceive something that may likely be understood as “historic” in the future while it is still unfolding.

Anthea Hartig: The NMAH has an ongoing commitment to documenting the spirit of American democracy and political processes. This includes how people express their opinions through rallies, protests, presidential campaigns, and elections. Curators from the museum's Political History Division have attended and collected objects and archival materials from the COVID-19 pandemic; and racial-, social justice–, and election-related events such as Black Lives Matter protests, women's marches, Dreamers protests, and the aftermath of the attacks on the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021.

The museum collects from contemporary events because many materials are ephemeral and, if not collected immediately, they are lost to the historical record. Curators assess available materials for how they represent the points of view expressed by the participants and how the First Amendment to the Constitution is exercised. Generally, new acquisitions include items like signs, pamphlets, buttons, and hats, which are either handmade by the owners or official materials distributed by organizers. Our experienced curators work to ensure an illustrative and inclusive collection while adhering to the highest professional ethics in collecting.

The Smithsonian has expanded and continues to augment its portfolio of museums. What are the benefits and what are the risks in this undertaking? Why do we need new, separate museums on the Mall to tell the stories of women and American Latinos in the United States?

Tey Marianna Nunn: As a long-time museum professional, I recognize that museums have not been inclusive in the past. That is one of the reasons I am so committed to this work. There is a movement now to rectify that, to be introspective and more authentic. We are excited about both the new Smithsonian American Women's History Museum (SAWHM) and the National Museum of American Latino (NMAL). As a Latina I am thrilled to know that stories that represent me will be highlighted in both museums. For a very long time, I did not see my experience reflected in museum exhibits and interpretation. We all want our stories told and approaches to telling stories can differ. No single museum can do it all. The Smithsonian will ensure that the full complexity of the American story will be told via our two new museums and our nineteen additional museums as well as our libraries, archives, and research centers. Women's history cannot be told in one single museum, nor can Latino history. Our experiences are so multifaceted, they can't be siloed. Creating new museums to highlight the contributions of women and Latinos contributes to the equity of representation on a national scale. They will help to validate the full American experience.

Michael Neufeld: In every case, the initiative for specialized museums has come from the outside, from communities who managed to mobilize congressional support for legislation. The Smithsonian leadership has always been concerned about the relentless expansion of our museum portfolio, in case the Institution's budget doesn't expand to meet the increasing responsibilities Congress lays upon us. When it became clear in each case that a congressional majority was forming to create a new museum, our leadership accepted that and went forward with it.

Like a lot of Smithsonian curators and American citizens, I was a little skeptical at first at the proliferation of specialized history and culture museums inside the Smithsonian. As we create more sectional museums, we obviously run the danger of balkanizing American history into separate ethnic, racial, or gender histories, undermining the universality that the American History Museum has sought to represent. Yet, it is clear that the public and the represented communities appreciate the greater depth of exhibitions and artifacts that museums like the National Museum of the American Indian and the National Museum of African American History and Culture can present. They are also an important mechanism for righting the wrongs created by centuries of discrimination, and they present American history as it actually is, in all its diversity. The National Museum of the American Latino and the Smithsonian American Women's History Museum will extend that trend. There can be a synergy among Smithsonian history and culture museums if we cooperate with each other, and share artifacts, outreach, and staff expertise. If we do that, we can strengthen the collective presentation of American history on the National Mall, rather than balkanizing it.

Damion L. Thomas: The benefits of the expansion are that we have more entry points into our national conversations. These museums will help foreground different questions, histories, and social movements.

Samir Meghelli: As just one example, anyone who visits the National Museum of African American History and Culture can quickly see the tremendous value of expanding the narratives of—and perspectives on—our history and offering a much richer view of our collective past. The risk is merely the criticism that some already lodge—and that some others inevitably will—that the fact of more museums somehow “fractures” or “fragments” history, leaving it too compartmentalized and lacking in a unitary vision/version of American history. But I'm not convinced that more history is ever bad for history. The more entry points into understanding the past that are offered, the more lenses onto our nation's complex history that can be presented, the more contributions of minoritized peoples (those who've been historically excluded from mainstream museums) celebrated, the better.

Anthea Hartig: The growth and expansion of the Smithsonian's museum offerings are a boon for the visitors we serve. It allows them to adjust the aperture through which they encounter, process, and learn U.S. history. My hope is they first widen the lens beginning their experience at the National Museum of American History for a broad scope and scale of America's ideals, promises, and triumphs as well as its shortcomings, tragedies, and failures. Then, focus the lens by exploring the heritage museums for deeper dives into America's challenging complexities, diverse cultural landscape, and motivational changemakers. The beauty of this will be the perfect picture of what a shared future together can look like at the Smithsonian.

In its efforts to broaden definitions of historical scholarship beyond only the creation of “new knowledge,” the American Historical Association (AHA) has highlighted the Smithsonian Institution's mission, first articulated in 1846, which advances a broader aim: “the increase and diffusion of knowledge.” What does the Smithsonian's diffusion of knowledge look like in practice? How could/should it be applied to the historical profession?

Michael Neufeld: That definition of our mission actually goes back to James Smithson's will from the 1820s. After a decade of wrangling over what to do with this unexpected, and for some politicians, unwanted posthumous gift from an English gentleman scientist, in 1846 Congress finally legislated into existence a research institution, led by the leading American scientist of his day, Joseph Henry. “Diffusion” primarily took the form of publications and lectures. The museum function did not become dominant until the 1870s or later, with the establishment of the U.S. National Museum adjacent to the Castle. Even today, research in the biological sciences, earth and planetary sciences, and astronomy and astrophysics, remains a large part of what the Smithsonian does. A lot of our diffusion today through museum exhibits, websites, podcasts, social media, etc., is about science, although history and art history are also prominent. (NASM is actually a hybrid; part science museum, part history of technology museum.)

Like every other cultural institution, the Smithsonian is adapting to the proliferation of electronic media. Museum visits are dwarfed in numbers, if perhaps not in effectiveness, by interactions with our online exhibits, web sites, and media. Diffusion obviously has many more dimensions these days. Academic historians can certainly learn from, and build upon, the outreach of history museums in trying to reach the public with a more complex and multifaceted view of their own past. As a historian who worked as a curator for over thirty-two years, I certainly learned to think about how to reach a broad audience, not just my colleagues in the academy. I've come a long way from my graduate training, when we were taught to look down on popular writing as selling out.

Tey Marianna Nunn: Early in the history of the Smithsonian, the quote read: “For the increase and diffusion of knowledge among men.” The original motto didn't include women, gender diversity, or diversity in general. Nor did it mention rural populations and underrepresented communities. It certainly didn't mention children, millions of whom increase their knowledge every year via Smithsonian resources. The Smithsonian Institution with its twenty-one museum, twenty-one libraries and archives, and numerous research centers is a trusted source on both a national and global level. The Covid pandemic helped us to dramatically diffuse knowledge virtually, increasing digital connectivity and the ability to reach many different populations, more than ever, rather than being DC centric. As I mentioned earlier, the SAWHM is beginning with an innovative virtual museum long before our physical museum is built. While we are gearing up for that, we are simultaneously doing in-person programming and our teaching because we know the two go hand in hand.

Damion L. Thomas: The diffusion of knowledge at the Smithsonian is guided by our role as a public institution, which means that we should be responsive to the needs and interests of the general public. That means that our exhibitions and programming should be guided by our responsibility to provide learning opportunities and moments of reflection for American citizens. In practice, that often means taking scholarly work and presenting it in a manner that helps people from all backgrounds access, engage, and discuss these core national issues.

Anthea Hartig: We are grateful to our partners at the AHA (and the Organization of American Historians, the National Council on Public History, and others) for understanding and elevating our history mission at the Smithsonian. Our commitment to integrated, interdisciplinary research, scholarship, and education remain both the mark and the aspiration of the Institution as we focus on expanding our reach, relevance, and impact. If we think of the NMAH as the nation's largest history classroom and in line with our vision, we daily commit to our expansive vision, and ours and the nation's ongoing reckoning with the complexities of our pasts.

As historians, we are tellers of stories, seekers of truths, embracers of nuance, ambassadors of empathy, and defenders of unalienable rights. That history is a prime tool of social justice and personal growth only continues to grow more resolute in my mind. History for me is the key that unlocks the mysteries of humanity, of meaning, of place, of conquest, of love, of power and of self.

If we think then about our dual roles as both active participators in history and in telling the stories about history, we can situate ourselves in place and in story. Start by thinking about the land and that lies atop and below the surface, as place first allows us to understand its complex layers and weave of human encounters, and as our native colleagues have always known, the sacredness of the land. Second, embrace our roles as storytellers, as narrators—we shape perceptions about the past's value by the way we tell stories, by how we tell them, who we include and exclude, and what we emphasize. Stay true and stay humble.

Samir Meghelli: The dual mission of the larger Institution—both the creation or advancement (“the increase”) of new knowledge and its “diffusion”—are central to the work of our museum. That original research on which each exhibition is based is permanently archived in our collections, available to future students, scholars, and community members. But it also serves as the foundation for our exhibitions, public programs, books, and other intellectual “products.” Just as one recent example of both the “increase” and “diffusion” of new knowledge, for our A Right to the City exhibition, we conducted research in archives across the DC region, conducted nearly 200 oral history interviews, took thousands of photographs of contemporary neighborhood change and community organizing efforts, engaged in community collecting of artifacts and archives, and worked with several community-based organizations to find a permanent home for their papers. In addition to the physical exhibition at the museum, we also brought much of its content online through creating a digital exhibit. And maybe most significantly, we partnered with the DC Public Library to install smaller satellite exhibits at libraries that featured neighborhood-specific histories drawn from the main exhibition. We collaborated with libraries across the city to host book talks that brought scholars into conversation with local communities and also documentary film screenings with filmmaker Q&As. We also collaborated with American University's newly unveiled “Humanities Truck,” a food truck–sized vehicle retrofitted to showcase curated content drawn from the museum exhibition. We brought the truck to street festivals and other events across the city. We also partnered with American University's School of Communication to create a “DC Storytelling Hotline” using repurposed payphones that we installed in the museum exhibition and at the satellite library exhibits, which featured clips from oral histories that we had conducted as part of the research for the exhibition, but which also allowed people to record stories of their own. These were just a few of the creative ways we sought to render new historical knowledge accessible to a broader public, as in what “diffusion of knowledge” can look like in practice.

In addition to the peer-reviewed journal article and monograph that the historical profession has long prized, there is room for—and indeed, potentially great benefit in—valuing the many creative ways that deep and original historical research finds other meaningful avenues of “diffusion,” particularly those that reach a public that extends beyond just the academy. In giving due weight to original historical scholarship that takes the form of exhibitions (both physical and digital), oral history projects, a variety of community-engaged history initiatives, and other public-facing scholarly projects, the historical profession can only be enriched and expanded—both in who is welcomed as a contributing member to the profession and in who can be reached, informed, and inspired by new historical knowledge.