No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 July 2019

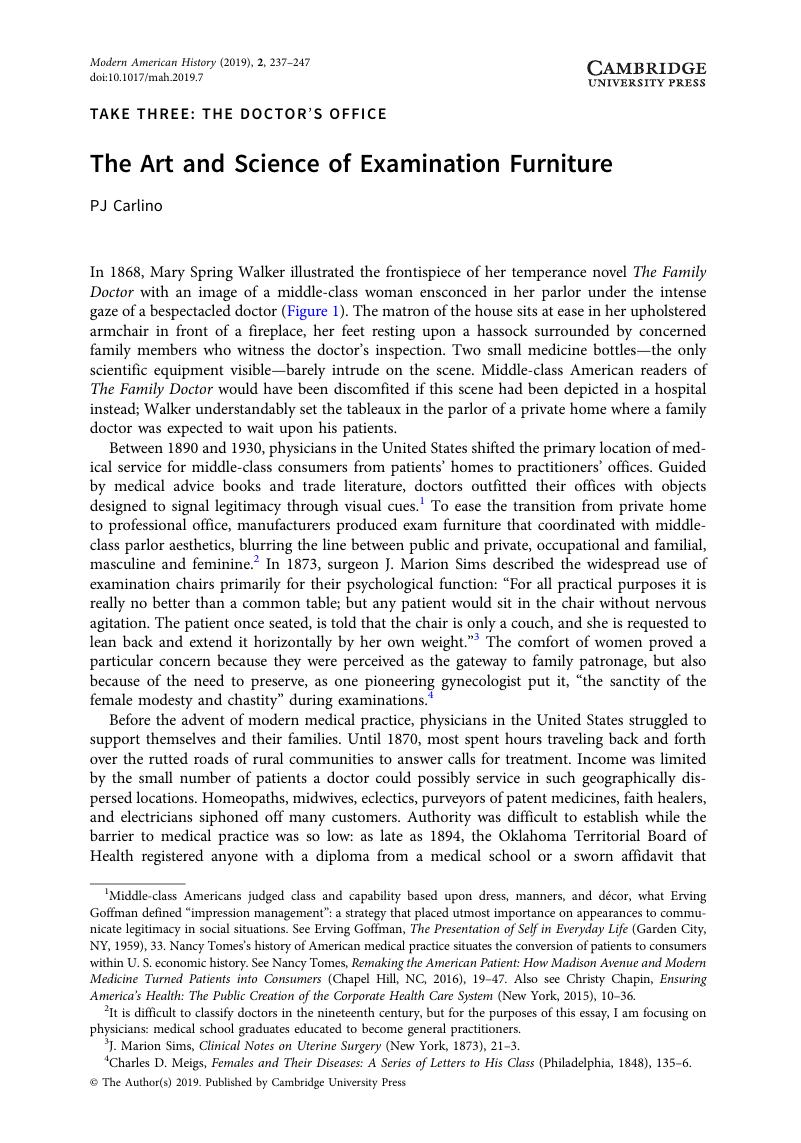

1 Middle-class Americans judged class and capability based upon dress, manners, and décor, what Erving Goffman defined “impression management”: a strategy that placed utmost importance on appearances to communicate legitimacy in social situations. See Goffman, Erving, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (Garden City, NY, 1959), 33Google Scholar. Nancy Tomes's history of American medical practice situates the conversion of patients to consumers within U. S. economic history. See Tomes, Nancy, Remaking the American Patient: How Madison Avenue and Modern Medicine Turned Patients into Consumers (Chapel Hill, NC, 2016), 19–47Google Scholar. Also see Chapin, Christy, Ensuring America's Health: The Public Creation of the Corporate Health Care System (New York, 2015), 10–36CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

2 It is difficult to classify doctors in the nineteenth century, but for the purposes of this essay, I am focusing on physicians: medical school graduates educated to become general practitioners.

3 Sims, J. Marion, Clinical Notes on Uterine Surgery (New York, 1873), 21–3Google Scholar.

4 Meigs, Charles D., Females and Their Diseases: A Series of Letters to His Class (Philadelphia, 1848), 135–6Google Scholar.

5 “Traveling Quack Doctors,” Democrat and Chronicle, Oct. 2, 1885, 4.

6 Starr, Paul, The Social Transformation of American Medicine (New York, 1982), 61–78Google Scholar; Johnson, David A. and Chaudhry, Humayun J., Medical Licensing and Discipline in America: A History of the Federation of State Medical Boards (Lanham, MD, 2012), 47Google Scholar; Rosenkrantz, Barbara, “The Search for Professional Order in 19th-Century American Medicine,” in Sickness and Health in America: Readings in the History of Medicine and Public Health, 3rd edition, ed. Leavitt, Judith and Numbers, Ronal L. (Madison, WI, 1997), 219–32Google Scholar; Pescosolido, Bernice A. and Martin, Jack K., “Cultural Authority and the Sovereignty of American Medicine: The Role of Networks, Class, and Community,” Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 29, nos. 4–5 (Aug.–Oct. 2004): 735–56CrossRefGoogle ScholarPubMed; Furst, Lilian R., Between Doctors and Patients: The Changing Balance of Power (Charlottesville, VA, 1998), 94–5Google Scholar.

7 Starr, The Social Transformation of American Medicine, 61–78; Tomes, Remaking the American Patient, 20–5.

8 Starr, The Social Transformation of American Medicine, 79–142.

9 Tomes, Remaking the American Patient, 24.

10 Johnson and Chaudhry, Medical Licensing and Discipline in America, 10; “Medical Education in the United States: Annual Presentation of Educational Data for 1922 by the Council on Medical Education and Hospitals,” Journal of the American Medical Association 79, no. 8 (Aug. 19, 1922), 629–33; Howell, Joel D., “Making a Medical Practice in an Uneasy World: Some thoughts from a Century Ago,” Academic Medicine 72, no. 11 (Nov. 1997): 977–81CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

11 “Home and Foreign Gossip,” Harper's Weekly, Nov. 18, 1871, 1079.

12 Cathell, D. W., The Physician Himself and Things that Concern His Reputation and Success, 9th edition (Baltimore, 1890), 10Google Scholar.

13 On the meanings American women invested in such décor, see Grier, Katherine C., Culture & Comfort: Parlor Making and Middle-Class Identity, 1850–1930 (Washington, DC, 1988), 22–63, 89–116Google Scholar.

14 W. D. Allison and The Perfection Chair Company, both of Indianapolis, were the most prominent manufacturers of examination chairs and tables, but at least six others firms manufactured nearly identical forms.

15 Charles Truax & Co., Price List of Physicians’ Supplies, 6th Edition (Chicago, 1893), 867Google Scholar.

16 Johnson and Chaudhry, Medical Licensing and Discipline in America, 20; Starr, The Social Transformation of American Medicine, 41–2.

17 Charles Eastlake was an architect and proponent of the English Art and Crafts movement. His book, published in 1868, was widely read in the United States. Eastlake, Charles Locke, Hints on Household Taste in Furniture, Upholstery and Other Details (London, 1868)Google Scholar.

18 Beecher, Catherine and Stowe, Harriet Beecher, The American Woman's Home, Or, Principles of Domestic Science (New York, 1869), 84Google Scholar. Magazines that provided advice on the creation of aesthetically pleasing and therefore moral homes included Godey's Lady's Book, The Ladies’ Repository and Home Magazine, and Harper's Weekly.

19 The parlor table was the location for the display of religious objects that communicated a family's piety to visitors. See Grier, Culture and Comfort, 91.

20 Cone, Ada, “Aesthetic Mistake in Furnishing—The Parlor Center Table,” The Decorator and Furnisher 17, no. 4 (Jan. 1891): 132CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

21 Grier, Culture and Comfort, 185–186.

22 Charles Truax & Co., Price List of Physicians’ Supplies, 5th Edition (Chicago, 1890), 587Google Scholar.

23 Pescosolido and Martin, “Cultural Authority and the Sovereignty of American Medicine.”

24 Lewis, Sinclair, Arrowsmith (New York, 1925), 85–7Google Scholar. The fictional Dr. Gaeke, vice president of the “New Idea Medical Instrument and Furniture Company of Jersey City,” gives a speech titled “The Art and Science of Furnishing the Doctor's Office,” describing “The Tapestry School” versus the “Aseptic School,” in doctor's office furnishings styles.

25 Ibid.

26 Tomes, Remaking the American Patient, 27, 38.

27 Starr, The Social Transformation of American Medicine, 76; “The Business Side of Practice,” The Osteopathic Physician 25, no. 3 (Mar. 1914): 5–6.