Introduction

Silica clathrates (or clathrasils) are zeolite-like materials constructed of pure silica framework structures with small cage-like voids. Melanophlogite, a rare silica mineral first reported from Sicily, Italy in the 19th century (von Lasaulx, Reference von Lasaulx1876), is the first example of a silica clathrate. Melanophlogite's chemical composition was at first considered to be essentially SiO2, and the >6 wt.% C, H and S detected by chemical analyses were thought to be impurities of organic matter trapped as inclusions (Skinner and Appleman, Reference Skinner and Appleman1963). It turned out to have a crystal structure similar to the cubic structure-I gas hydrate that can incorporate organic molecules (Kamb, Reference Kamb1965). Gas molecules such as CH4, CO2, N2 and H2S have been reported in natural melanophlogite and noble gases as well as other small molecules can be incorporated into the cages (Gies et al., Reference Gies, Gerke and Liebau1982; Yagi et al., Reference Yagi, Iida, Hirai, Miyajima, Kikegawa and Bunno2007; Tribaudino et al., Reference Tribaudino, Artoni, Mavris, Bersani, Lottici and Belletti2008). Starting from the 1980s, a variety of silica clathrates such as melanophlogite, dodecasil-3C and dodecasil-1H, as well as pure silica zeolites (zeosils) have been synthesised successfully and studied (e.g. Gies et al., Reference Gies, Gerke and Liebau1982; Gies Reference Gies1984, Gerke and Gies, Reference Gerke and Gies1984). For each unique framework topology, the framework type code (FTC) consisting of three capital letters (in bold type) are assigned by the Structure Commission of the International Zeolite Association (IZA-SC) (Baerlocher et al., Reference Baerlocher, McCusker and Olson2007). The FTC of melanophlogite is MEP.

Chibaite from the Chiba Prefecture, Japan was the second silica clathrate found in Nature (Momma et al., Reference Momma, Ikeda, Nishikubo, Takahashi, Honma, Takada, Furukawa, Nagase and Kudoh2011). It has the MTN-type framework structure and it is isostructural with the cubic structure-II hydrate. Associated with chibaite, another silica clathrate mineral that is isostructural with the hexagonal structure-H gas hydrate (Lu et al., Reference Lu, Seo, Lee, Moudrakovski, Ripmeester, Chapman, Coffin, Garder and Pohlman2007) was also found. This mineral has been fully characterised and named as bosoite (Momma et al., Reference Momma, Ikeda, Nagase, Kuribayashi, Honma, Nishikubo, Takahashi, Takada, Matsushita, Miyawaki and Matsubara2014). Bosoite is the natural analogue of a synthetic silica clathrate compound with the DOH-type framework structure, known as dodecasil-1H (Gerke and Gies, Reference Gerke and Gies1984). The mineral and its name were approved by the International Mineralogical Association (IMA) Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature and Classification (IMA2014-023). The mineral is named after the Boso Peninsula, the large peninsula just east of Tokyo across the Tokyo Bay. Type material has been deposited in the collections of the National Museum of Nature and Science, Japan, registered number NMS-M43775 and the Tohoku University Museum, Aoba, Sendai, Japan, mineral collection specimen A-153. A single-crystal X-ray diffraction study was done for both the holotype and cotype (NMS-M43763) samples, and data of the cotype are reported here.

Occurrence

Bosoite occurs in association with chibaite, which was found from Arakawa, Minami-boso City, Chiba Prefecture, Japan (Momma et al., Reference Momma, Ikeda, Nishikubo, Takahashi, Honma, Takada, Furukawa, Nagase and Kudoh2011). The Boso Peninsula encompasses the entire Chiba Prefecture located in the middle of the Honshu Island, and Arakawa is located in the south of the Peninsula. Bosoite and chibaite occur in small quartz and calcite veins partly developed at fault planes in tuffaceous sandstone and mudstone of the Miocene Hota Group. They are considered to be a series of forearc sediments deposited near the plate margin by the Palaeo–Izu arc and accreted along the proto-Sagami trough by subduction of the Philippine Sea plate during the Early to Middle Miocene (Ogawa and Ishimaru, Reference Ogawa and Ishimaru1991; Takahashi et al., Reference Takahashi, Shibata, Hirata and Niida2016).

The sequence of mineral formation from rim to centre of the vein is generally as follows: a very thin layer of clinoptilolite-(Na) and/or opal-A, melanophlogite, chibaite, bosoite and calcite. Melanophlogite ‘crystals’ were always found as cubic forms of semi-translucent quartz pseudomorphs, with only one exception of an unaltered sample. Many of chibaite ‘crystals’ are also altered and occur as white quartz pseudomorphs. Some parts of the veins are composed of primary quartz grains or microcrystalline chalcedony. Other associated minerals are pyrite, dachiardite, sepiolite, gypsum and baryte. These minerals were identified by a Gandolfi XRD camera and scanning electron microscopy/energy dispersive X-ray spectrometry (SEM/EDS). The mineral was formed under low-temperature hydrothermal conditions during diagenesis.

Physical and optical properties

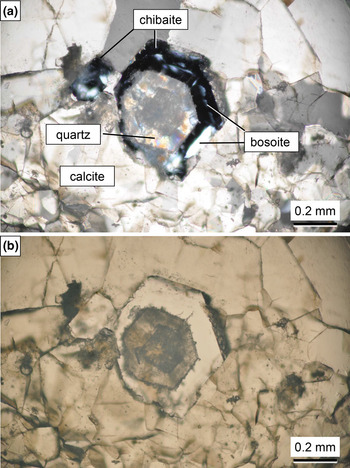

Bosoite occurs as an epitaxial intergrowth on chibaite, where the {0001} face of hexagonal bosoite is parallel to the octahedral {111} of chibaite (Figs 1 and 2). It exhibits platy shapes parallel to {0001}. The grain size of an individual crystal is ~0.01 mm to 0.05 mm thick and 0.05 mm to 0.3 mm in diameter. Crystals are transparent and colourless, have a white streak and a vitreous lustre. Crystals are brittle with an irregular fracture. The Mohs hardness is estimated to be 6½–7 by scratching a thin section sample by hard metal needles. It is non-fluorescent under shortwave or longwave ultraviolet radiation (254 and 365 nm). The density could not be measured because of the small grain size. The calculated density is 2.04 g/cm3 based on the empirical formula Na0.01(Si0.98Al0.02)Σ1.00O2⋅0.50CH4. It is optically uniaxial (+). Due to the small amount of sample available the refractive indices could not be determined. Through observation of the Becke line at grain boundaries between bosoite and chibaite under a polarised light microscope equipped with universal stage, the refractive index (n ω) of bosoite was found to be slightly higher than that of chibaite, which is optically isotropic and n = 1.470(1).

Fig. 1. Photomicrographs of bosoite sample (NSM-M43775) under crossed polarised light (a) and plane polarised light (b). The quartz domain inside chibaite is a pseudomorph of chibaite. The slightly darker area inside the quartz domain is also chibaite overlapped with quartz (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Back-scattered electron image (BSE) of the sample (NSM-M43775). Bosoite is observed to be slightly darker than chibaite in BSE because the framework density of bosoite (18.0 tetrahedral atoms per 1000 Å3) is lower than that of chibaite (18.7 tetrahedral atoms per 1000 Å3).

Raman spectroscopy

Raman spectra (Fig. 3) were measured using a JASCO NRS-5100 spectrometer. Spectra were obtained using a 532 nm laser with the 600 grooves/mm grating and a 100× objective lens. A list of Raman shift positions of the hydrocarbon molecules measured in bosoite are given in Table 1 along with those in the free gas state, in chibaite, and in melanophlogite for comparison. The presence of hydrocarbons is shown by bands in the range 2850 to 3050 cm–1. In the C–H stretching bands, existence of CH4, C2H6, and C3H8 or even larger molecules were detected. However, the Raman bands of this region from C3H8 or larger molecules do not resolve very well. Signals of C–C stretching bands (~850–1000 cm–1) could not be detected owing to the high background levels and low signal-to-noise ratios. Therefore, the existence of molecules larger than C4H10 could not be confirmed. A small peak observed at 1456 cm–1 corresponds to the CH3 degenerate-deformation modes of alkanes with > 2 C atoms. Raman bands of other possible guest molecules, which have been reported in melanophlogite and chibaite, are as follows. N2: 2321 cm–1; CO2: 1277 and 1378 (Kolesov and Geiger, Reference Kolesov and Geiger2003) or 1380 cm–1 (Kanzaki, Reference Kanzaki2019); H2S: 2594 and 2604 cm–1 (Tribaudino et al., Reference Tribaudino, Artoni, Mavris, Bersani, Lottici and Belletti2008). Raman bands attributable to guest molecules other than hydrocarbons were not observed in bosoite.

Fig. 3. The Raman spectrum of bosoite (NSM-M43775): (a) the whole measured range and (b) enlarged view of the C–H stretching region, overlaid with Raman spectra of chibaite and melanophlogite from the same locality for comparison. Background is subtracted from the data.

Table 1. Raman band positions of hydrocarbons in bosoite.

aKolesov and Geiger (Reference Kolesov and Geiger2003), bSum et al. (Reference Sum, Burruss and Sloan1997), cSubramanian et al. (Reference Subramanian, Kini, Dec and Sloan2000), dMomma et al. (Reference Momma, Ikeda, Nishikubo, Takahashi, Honma, Takada, Furukawa, Nagase and Kudoh2011), eShimanouchi (Reference Shimanouchi1972), fLikhacheva et al. (Reference Likhacheva, Goryainov, Seryotkin, Litasov and Momma2016).

Chemical composition

Three quantitative chemical analyses were carried out by means of an electron microprobe (JEOL JXA- 8800M, WDS mode, 15 kV, 5 nA and 1 μm beam diameter). Standard materials for quantitative analyses of the samples were: quartz for Si, corundum for Al and jadeite for Na. The acquired X-ray intensities were corrected by the ZAF method. The analytical results are given in Table 2. Hydrocarbon contents were not measured directly because of the small amounts of material available and thus their quantitative ratios remain undetermined. The total hydrocarbon is given based on the difference and is reported as CH4/C2H6/C3H8. The empirical formula (based on 2 O atoms per formula unit with an assumption that all the hydrocarbon is CH4), with rounding errors, is Na0.01(Si0.98Al0.02)Σ1.00O2⋅0.50CH4.

Table 2. Chemical compositions of bosoite.

*Calculated based on the total. S.D. – standard deviation.

A suitable simplified formula is not a straightforward choice since, as noted above, a number of guest molecules could be accommodated in the clathrate. Based on the results of the single-crystal refinement showing a large number of site-scattering factors in the largest cage, the broad Raman bands within the C–H stretching region, and previous studies reporting the necessity of large molecules for crystallisation of the DOH-type clathrasil (Gies and Marker, Reference Gies and Marker1992; van Koningsveld and Gies, Reference van Koningsveld and Gies2004), hydrocarbon molecules larger than C4H10 are very likely to be included. Assuming just the presence of alkanes in the mineral, the simplified formula is SiO2⋅nCxH2x+2, where x denotes average degree of polymerisation for alkanes and the limit of (n × x) ≤ ~0.5. More details about guest molecules are discussed in the Crystallography section below. The stoichiometry SiO2⋅0.5CH4 requires SiO2 88.22, CH4 11.78, total 100.00 wt.%.

Crystallography

Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) data of the holotype sample were collected by the Debye-Scherrer method with synchrotron radiation using an imaging plate at BL15XU, SPring-8, Japan. As bosoite is always associated with chibaite, the chibaite crystals were separated carefully from the host rock and crushed in an alumina mortar. The obtained powder was sealed in a Lindemann glass capillary tube with inner diameter of 0.5mm. Experimental conditions were as follows: λ = 0.652973 Å; exposure time = 6 s; and step interval = 0.003°. Data from 3.05° to 56° were used for refinement of unit cell parameters by Rietveld analysis using RIETAN-FP (Izumi and Momma, Reference Izumi and Momma2007). Atomic coordinates of bosoite were fixed at values reported by Gerke and Gies (Reference Gerke and Gies1984) and only occupancies of guest sites and isotropic atomic displacement parameters were refined. For chibaite, both the cubic and tetragonal structural models were used because the symmetry of part of chibaite crystals is low (Momma et al., Reference Momma, Ikeda, Nishikubo, Takahashi, Honma, Takada, Furukawa, Nagase and Kudoh2011). Although fitting by two structural models for almost perfectly overlapping peaks might have caused overfitting of chibaite parameters, it was still preferable to retrieve better unit-cell parameters of bosoite. The refinement converged to R wp = 3.41%, R p = 2.31%, Gof = 15.17, R Bragg(bosoite) = 4.44%, RF(bosoite) = 2.09%. Note that the high Gof value is due to extremely high signal / background ratio of data. The refined unit-cell parameters of bosoite are a = 13.8725(3), c = 11.2694(3) Å and V = 1878.18(8) Å3. The refined fraction of each phase is as follows: 2.7 wt.% bosoite; 19 wt.% cubic chibaite; 76 wt.% tetragonal chibaite; 0.9 wt.% quartz; and 1.4 wt.% calcite. Almost all PXRD data of chibaite samples showed the existence of ~2–3 wt.% of bosoite. Diffraction data are shown in Fig. 4 and listed in Table 3.

Fig. 4. Observed (black cross) and calculated (solid red line) powder diffraction pattern of sample (NSM-M43775). Tick marks below the pattern indicate diffraction position of bosoite (black), tetragonal phase of chibaite (magenta), cubic phase of chibaite (red), quartz (blue) and calcite (green). Data points from 9.0 to 9.3° were not used in the refinement because a broad halo from opal-A appearing at this range overlaps with a small bosoite peak. When this data range was used, the halo caused significant overestimate of I o of the overlapped bosoite peak, leading to drifts of various parameters of bosoite.

Table 3. Powder X-ray data (d in Å, I in %) with normalised intensity of bosoite.

Theoretical powder data are calculated on the basis of the structural model refined by Rietveld analysis using RIETAN-FP. For unobserved or overlapped peaks, only calculated lines with I > 1 are shown. The strongest lines are given in bold.

*These diffraction peaks were overlapped with peaks of other minerals in the powder sample, i.e. chibaite, quartz and calcite.

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SXRD) studies were carried out using a Rigaku R-Axis Rapid II microdiffractometer with CuKα radiation from the VariMax rotating-anode target combined with a confocal mirror. The epitaxial relation of bosoite and chibaite was confirmed from the holotype sample. However, due to overlap of diffraction peaks of chibaite and bosoite, even small volumes of chibaite associated with bosoite prevented us from doing the structure refinement of bosoite. As the two minerals cannot be distinguished under normal stereomicroscope, we had to make several thin sections to find and cut out a single-crystal of bosoite under polarised light. We decided not to consume the holotype for this purpose and used the cotype because the holotype is much better as a specimen but smaller than the cotype. The Rigaku RAPID AUTO software package (Rigaku, 1998) was used for processing the diffraction data, including the application of numerical absorption correction. The structure was solved by the charge flipping method using Superflip (Palatinus and Chapuis, Reference Palatinus and Chapuis2007). From the electron-density distributions obtained by the charge flipping method, space group P6/mmm reported by Gerke and Gies (Reference Gerke and Gies1984) was confirmed. All the framework atoms and two guest sites in the small cages were found by the charge flipping method. The rest of the guest sites were found by difference-Fourier syntheses. For the refinement of crystal structure, SHELXL-2018/1 software (Sheldrick, Reference Sheldrick2008, Reference Sheldrick2015) was used, with neutral atom-scattering factors. Details of the data collection, refinement, and results of the refinement are summarised in Table 4.

Table 4. Data collection and details of the single-crystal structural refinement.

An illustration of the average crystal structure is shown in Fig. 5. Refined atomic coordinates and equivalent isotropic displacement parameters are summarised in Table 5. Selected bond distances and bond angles are given in Table 6. From the difference-Fourier map, all of oxygen atom positions were found to be split around their average positions. Subsequent refinements with all the O sites split around their average positions greatly reduced the residual electron densities and improved R1 from 4.26% to 2.96% with a trade-off of poorer data / parameter ratio. The mean U eq of O sites also changed from 0.076 Å2 to 0.039 Å2. To reduce the number of free parameters and their correlations, occupancy of each split O site was fixed at ⅓ and the position of each O site was restrained such that it is placed equidistant from neighbouring Si sites. Anisotropic displacement components of the split O atoms along the adjacent O–O direction were also restrained to be equal by using the DELU instruction. The crystallographic information files containing results of the refinements based on the average and split models have been deposited with the Principal Editor of Mineralogical Magazine and are available as Supplementary material (see below).

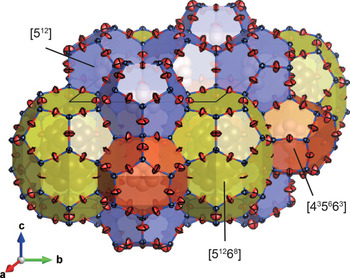

Fig. 5. The average framework structure of bosoite refined without splitting of O sites.

Table 5. Refined atomic position and equivalent isotropic displacement parameters (Å2) of the average model.

*U iso were refined with their values constrained to the same.

Table 6. Selected bond distances and bond angles in bosoite.

The unit cell of bosoite consists of three types of cages: two [435663] cages, three [512] cages and one [51268] cage (here [4i5j6k] denotes a polyhedron having i quadrilateral, j pentagonal and k hexagonal faces). The former two types of cages are relatively small and mainly occupied by CH4. C1 and C2 atoms are those of CH4 molecules at the centre of [435663] and [512] cages respectively, and their U eq are relatively large owing to very weak van der Waals interaction with the host framework. Occupancies of these sites were fixed at 1 because they exceeded 1 when freely refined. Furthermore, the difference-Fourier map still showed small residuals around C1 and C2 atoms. Distances from C1 and C2 atoms to the residuals were ~1 Å and these residuals were interpreted as orientationally disordered hydrogen atoms of CH4. When these H atoms were included in the refinement with their U iso values constrained to the same and C–H distances fixed to 1.08 Å, R indices decreased ~0.3%. In the final refinement of the average model, these H atoms are not included because they are less reliable, whereas they are included in the split model for reference. In the largest [51268] cage, large molecules or multiple number of small molecules are included. The total site-scattering factor in the [51268] cage, refined as occupancies of C, was 81 e –. The refined U iso of C3A to C3E in the [51268] cage are extremely large owing to the variety of guest species and their static/dynamic disorder. Therefore, guest species and their ratio in the [51268] cage could not be interpreted. Depending on average degree of polymerisation for alkanes, 81 e – corresponds to 8.1 CH4, 4.5 C2H6, 3.12 C3H8, or 2.38 C4H10 molecules. When these four cases are considered, the total number of guest C atoms in the unit cell is ~13.1–14.5. Assuming that widely spread electrons of H atoms in the [51268] cage were not fully reflected to the refined site-scattering factor, and the [51268] cage is occupied mainly by large hydrocarbons, these numbers are within an acceptable range compared to the number estimated by the chemical analysis (17C per unit cell).

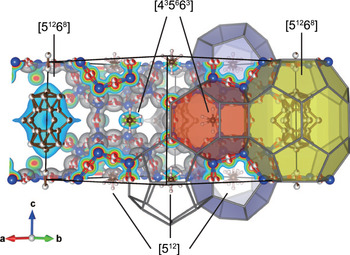

The electron-density distribution in bosoite calculated by the maximum entropy method (MEM) is shown in Fig. 6. Dysnomia (Momma et al., Reference Momma, Ikeda, Belik and Izumi2013) with the L-BFGS algorithm was used for calculation and VESTA (Momma and Izumi, Reference Momma and Izumi2011) was used for visualisation. To reduce correlation of residuals |F o – F c| / σ(F o) with d spacing of reflections, an exponential-type weighting scheme proportional to m × exp(–A/d) was used, where m is multiplicity of reflections and A is a weighting parameter optimised as 12.7. The electron-density distribution also confirms that all cages are almost fully occupied.

Fig. 6. Electron-density distribution in bosoite determined by MEM analysis overlapped with the split atom model. Isosurface level is 0.5 e –/Å3.

Discussion

The order of crystallisation of melanophlogite, chibaite and bosoite observed in the present study indicates a decisive role of guest molecules on their crystallisation. The [512] cage is common to all three minerals. Other types of cages making-up these minerals are: the [51262] cage in melanophlogite, the [51264] cage in chibaite as well as the [435663] and the [51268] cages in bosoite. The [51268] cage is the largest and the [512] cage is the smallest among them, whereas the [435663] cage is comparable in size to the smallest [512] cage. From the previous studies on syntheses of these clathrasils, the presence of large molecules matching in size to the largest cage in the crystal structure is considered as a necessary condition for their crystallisation (e.g. van Koningsveld and Gies, Reference van Koningsveld and Gies2004). This model can explain why bosoite was always found associated with chibaite crystals and why it is so minor in volume compared to the other two. The [51262] cage in melanophlogite can incorporate small gas molecules such as CH4, CO2, N2 and H2S, which are abundant gases in Nature. As a result, among these clathrasils, melanophlogite is the most abundant and the first phase to crystallise in Nature. While C2H6 is also capable of fitting into the [51262] cage (Ohno et al., Reference Ohno, Strobel, Dec, Sloan and Koh2009), C3H8 or larger hydrocarbons are too large for melanophlogite. As a result, the concentration of these large molecules in hydrothermal solutions increases as melanophlogite crystallises, and eventually crystallisation of chibaite is initiated. Similarly, the increase of the concentration of even larger molecules that cannot fit into the chibaite structure would initiate crystallisation of bosoite. As bosoite grows, large molecules would be consumed easily and overgrowth of chibaite on bosoite also occurs. Larger hydrocarbons have higher molecular refraction. Therefore, the above model of crystallisation is also consistent with the fact that the refractive index of bosoite is higher than that of chibaite regardless that the framework density of bosoite is lower than that of chibaite. Our observation that melanophlogite was almost always found to be replaced by quartz indicates that melanophlogite is less stable than both chibaite and bosoite.

SiO4 tetrahedra in framework silicates are known to be very stiff, to a first approximation they behave more like rigid units which rotate and translate without distortion of the tetrahedra (Hammonds et al., Reference Hammonds, Dove, Giddy, Heine and Winkler1996). On the other hand, the apparently short Si–O distances are often reported for clathrasils as a consequence of local tilting of the SiO4 tetrahedra with the rigid-unit mode, where Si–O distances are almost constant but actual O atoms are distributed around the refined positions (Momma, Reference Momma2014). This is why in the refinement of bosoite without splitting of O sites, the mean value of Si–O distance (1.578 Å) apparently looks shorter than the predicted value, 1.609 Å, for tetrahedrally coordinated pure silica frameworks (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Gibbs and Ribbe1969; Wragg et al., Reference Wragg, Morris and Burton2008). Si–O–Si angles range from 154.0(4)° to 180° with a mean value of 170°, which is also larger than the average value of 154° ± 9 for pure silica zeolite frameworks (Wragg et al., Reference Wragg, Morris and Burton2008). With the splitting of O sites, mean values of Si–O distances and Si–O–Si angles changed to 1.604 Å and 156° respectively. The splitting of O sites due to local disorder has also been reported for synthetic MTN- and DOH-type clathrasils (Könnecke et al., Reference Könnecke, Miehe and Fuess1992; Miehe et al., Reference Miehe, Vogt, Fuess and Müller1993). In the case of melanophlogite and chibaite, the tilting of the framework SiO4 tetrahedra at ambient or low temperature causes lowering of their space group symmetries (e.g. Nakagawa et al., Reference Nakagawa, Kihara and Harada2001; Scheidl et al., Reference Scheidl, Effenberger, Yagi, Momma and Miletich2018). On the other hand, as was reported for the synthetic DOH-type clathrasil (Miehe et al., Reference Miehe, Vogt, Fuess and Müller1993), we could see no sign of symmetry lowering of bosoite even though all of the O sites were found to be split.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1180/mgm.2020.91

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Drs Masahiko Tanaka and Yoshio Katsuya for their support at BL15XU SPring-8 (Proposal No. 2007A4503) and Mr. Taiji Oyama of JASCO for his arrangement on Raman spectroscopy measurement at JASCO Laboratory. The authors also thank Dr Stuart Mills, Principal Editor and two anonymous reviewers for critical comments and suggestions. The preliminary SXRD data was obtained by KEK photon factory BL10A (PAC. No. 2012G112, 2014G173). This study was supported partially by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP24740359 and JP16H05742.