Introduction

ŠTO TE NEMA (Why are you not here?) is a travelling participatory monument constructed out of 8,372 Bosnian coffee cups (bcs. fildžani) to remember around 8,000Footnote 1 mainly (Bosnian Muslim) men and boys who were killed during the 1995 Srebrenica genocide. From 2006 to 2020, this initiative gathered Bosnian and global community members to commemorate Srebrenica Memorial Day on-site on 11 July. Besides remembering Srebrenica physically, TwitterFootnote 2 end-users and the ŠTO TE NEMA team employ the #ŠtoTeNema hashtag to provide more extensive access to commemorate the genocide in the digital realm. By using #ŠtoTeNema, they raised awareness of the genocide, which continues to be denied or/and ignored by perpetrators, the authorities of Republika Srpska and Serbia, and individuals around the globe. In this article, I am interested in what meanings Twitter users generate by utilising #ŠtoTeNema and its relation to other hashtags and modes (texts, visuals, hyperlinks, and metadata). Therefore, this research will proceed with the following tasks:

1. To explore who are the people/agents (re-)tweeting #ŠtoTeNema.

2. To inspect all the (re-)tweets that use #ŠtoTeNema (i.e., their content, including the message, visuality, other hashtags used, and the meaning-making).

3. To check whether the meanings generated on Twitter coincide with the meaning imposed by @StoTeNema official account.

One part of the literature on ŠTO TE NEMA has mainly focused on diaspora mobilisation, how it finds consensus within ŠTO TE NEMA (Karabegović Reference Karabegović2014) and engages with local communities and/or memory institutions, such as Srebrenica–Potočari Memorial Center (Karabegović Reference Karabegović2019). Another part has analysed the role of the arts (including ŠTO TE NEMA) in genocide prevention (Murphy Reference Murphy2021a) and the emerging new kinds of monuments (ŠTO TE NEMA as a case study (Murphy Reference Murphy2021b; Whigham Reference Whigham, Gutman, Wüstenberg, Dekel, Murphy, Nienass, Wawrzyniak and Whigham2023). This research investigates the mnemonic practices revolving around the digital presence of the ŠTO TE NEMA and aims to contribute to the research on digital memory in former Yugoslavia. I argue that as a digital mourning practice, ŠTO TE NEMA has become the unofficial face of Srebrenica remembrance.

This article responds to the call of third-wave memory studies scholars (Fridman Reference Fridman2022; Rigney Reference Rigney2018), inviting researchers to focus on the relationship between memory, activism, and a bottom-up approach instead of concentrating only on the traumatic past. The #Hashtag #memoryactivism study framework, suggested by Fridman (Reference Fridman2022, Reference Fridman, Gutman, Wüstenberg, Dekel, Murphy, Nienass, Wawrzyniak and Whigham2023), allows me to explore hashtag #ŠtoTeNema initiators, participants, and their place in memory politics. Regarding the importance of agency in transnational memory politics (Wüstenberg and Sierp Reference Wüstenberg and Sierp2020), I pay particular attention to the role of artist Aida Šehović, her team, and online users in raising awareness about the Srebrenica genocide not only on the local and regional but also on the global level. Thus, I focus on how people use Twitter's digital space to commemorate the Srebrenica genocide through #ŠtoTeNema as well as what other modes they employ to make sense of their message. Therefore, this work contributes to scholarship exploring how people use online spaces to confront dominant narratives that ignore massive atrocities and disseminate information, seeking wider recognition.

Srebrenica memory 28 years later

The 1995 Srebrenica Massacre, recognised as a genocide by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and the International Court of Justice (ICJ), remains the bone of contention in Bosnia and Herzegovina (further Bosnia) and the region (Nettelfield and Wagner Reference Nettelfield and Wagner2013, 18). In 2004, Republika SrpskaFootnote 3 acknowledged the atrocities but did not recognise the massacre as ‘genocide’Footnote 4 (Denti Reference Denti, Andersen and Tornquist-Plewa2016). Therefore, the Republika Srpska's official memory politics selectively commemorates only Bosnian Serb victims, ignoring the suffering of Bosniaks, Bosnian Croats, Bosnian, Roma, and others. Parallelly, denial, hatred, and glorification campaigns flourish in the transnationalFootnote 5 digital space. For example, one could search for the #NožŽicaSrebrenicaFootnote 6 or Remove Kebab meme (Ristić Reference Ristić2023) to observe the genocide celebration campaigns online. In 2021, Twitter and Google promised to moderate hate speech towards the Srebrenica genocide victims and remove content concerning the genocide denial on their platforms (RFE/RL's Balkan Service 2021). However, it is easy to note that this policy was never fully implemented. Ivana StepanovićFootnote 7 claims that hiring a few employees who speak the Bosnian–Croatian–Serbian (BCS) language could rapidly solve the problem. Nevertheless, multinationals like Google prefer using algorithms based on machine learningFootnote 8 as it costs less.

Although mourning and grief may not be forbidden, they are not deserved (Butler Reference Butler2003) or highly welcomed in Republika Srpska.Footnote 9 The new generation does not learn anything about the atrocities in schools; walls get constantly decorated with murals and graffiti glorifying Ratko Mladić, the Bosnian Serb general responsible for the genocide; families continue to wait for the remains of their beloved ones, as many are yet to be found and identified. Moreover, controversial figures and genocide deniers remain in the public sector (e.g., media, education, science, culture, and politics). According to the Srebrenica Genocide Denial Report (Srebrenica Memorial Center 2021, 4), certain individuals who were part of the Bosnian Serb political and military apparatus during the war currently occupy government positions at the state and entity levels. Despite the release of the Genocide Denial Law in 2021 and numerous lawsuits, no one has yet been punished (Srebrenica Memorial Center 2023, 3). Therefore, the Bosnian Serb authorities defend and patronise former political (Assmann Reference Assmann2021) and military leaders. Although 28 years after the genocide has passed, one may find signs glorifying the perpetrators rather than memorialising victims in today's Republika Srpska (Srebrenica Memorial Center 2021, 31).

Many years after the Bosnian war (1992–1995), traumascapes (Tumarkin Reference Tumarkin2005) flourish more than ever before as new massive graves are being found each year, and survivors keep fighting their fight for recognition. The denial of Srebrenica's genocide and the interpretation of this tragedy divide Bosnia's ethnic groups, leaving Bosnian society increasingly polarised.

Alternative commemorative initiative ŠTO TE NEMA

Before ŠTO TE NEMA launched its campaign on social media, it existed as an on-site commemorative initiative. It began in 2006, when artist Aida Šehović created a one-day performance at Baščaršija (old market square in Sarajevo, Bosnia) on 11 July, presenting 932 porcelain coffee cups (bcs. fildžani), mainly collected and donated by Women of Srebrenica. Footnote 10 The main idea was that the coffee served in fildžani remained undrunk following the title of the well-known song Što te nema (translated as Why are you not here?). Coffee drinking is one of the most important rituals of community and togetherness in Bosnian and post-Yugoslav societies. ŠTO TE NEMA was inspired by the story of a woman who lost her husband during the Srebrenica genocide, claiming that she misses him the most when she is having a coffee (Hafner Reference Hafner2020). In ŠTO TE NEMA, Šehović exercises the absence of the victims who could have had coffee with their loved ones if they had not been killed. After constructing the monument, Šehović's team respected the victims, pursuing the moment of silence and then cleaned the cups.

The first ŠTO TE NEMA performance in Sarajevo (2006) was done with no particular intention of organising it yearly. Nevertheless, it travelled for the following 14 years (2007-2020) to different European and North American cities,Footnote 11 where Bosnian diasporic communities invited Šehović to remount the monument (Hafner Reference Hafner2020; Karabegović Reference Karabegović2014). The imagined coffee ritual gathered the Bosnian and global community participants to remember Srebrenica's victims and survivors on 11 July, announced Srebrenica Memorial Day.Footnote 12 To complement the on-site activities, users commemorated the Srebrenica genocide and human loss on various social media platforms, including Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

In 2020, the nomadic monumentFootnote 13 of ŠTO TE NEMA finally collected more than 8,372 fildžani. This figure refers to the (non-final) number of victims officially registered and engraved on the Srebrenica-Potočari Memorial plaque. Once ŠTO TE NEMA collected 8,372 cups, people kept donating more, and Šehović did not feel like she should stop this process.Footnote 14 After setting up a nomadic monument at Srebrenica–Potočari Memorial Center to mark the 25th anniversary of the Srebrenica genocide, Šehović decided that a permanent version of ŠTO TE NEMA should be built there together with other artworks that thematise the Srebrenica genocide (Canadian Museum for Human Rights 2021). Therefore, the final iteration of ŠTO TE NEMA as a travelling monument was in 2020.

However, the project continued to live on in different ways, changing its forms. In 2022 summer, the Spatium Memoriae exhibition took place at the Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Sarajevo, where the archive of the ŠTO TE NEMA monument (horizontal shelving units displaying cups) was exhibited. Additionally, Šehović, who works in the education sphere holding workshops with different communities and talking about the Srebrenica genocide to prevent similar atrocities, has made the film about ŠTO TE NEMA and works on the permanent monument. In 2023, Šehović began a new body of work titled Street Signs. The Sarajevo – Kyiv version is made in response to the first anniversary of Russian aggression and a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Currently, the artist is very concerned about the devastating situation for civilians in Palestine. Hence, Šehović's works and activities aim to raise awareness of the genocide(s) and aggression against civilian populations.

Connective turn: digital media's impact on memory (and) activism

Today, digital media prevails as an integral part of our everyday reality. Its rise and development undoubtedly changed how we treat and understand memory. Hoskins (Reference Hoskins2011) calls this transformation a connective turn: radical networking (or hyperconnectivity (Hoskins Reference Hoskins and Hoskins2018b) and dissemination of memory forced by the emergence of digital technologies. It covers everything from archiving memories to disseminating them in massive quantities than ever before. If (traditional) broadcast media addresses passive viewers, current post-broadcast media counts on participation and high involvement (Hoskins Reference Hoskins, Garde-Hansen, Hoskins and Reading2009, Reference Hoskins and Hoskins2018a). Following the connective turn, Hoskins (Reference Hoskins and Hoskins2018a) introduces another concept called memory of multitude as he finds the notion of collective memory too outdated for the post-broadcast participatory era. He suggests ‘ … “the multitude” as the defining digital organisational form of memory beyond but also incorporating the self’ (Hoskins Reference Hoskins and Hoskins2018a, 85). The multitude highlights diverse experiences and perspectives within a larger social or cultural context. Thus, various individual and collective memories may exist within a group and contribute to the collective memory.

Hoskins’ ideas connect well with the themes in social media and participatory culture scholarship that enrich the theoretical framework of this work. One of them is convergence culture (Jenkins Reference Jenkins2006), which binds three concepts: media convergence, participatory culture, and collective intelligence. Convergence culture defines how traditional and digital media interact, merge and change the way people create, consume, and interact with content. According to Jenkins (Reference Jenkins2006), convergence encourages consumers to participate in media (co-)creation and dissemination actively. Instead of only passively consuming it, everyone may become a producer of media or its remix. Another relevant concept, networked publics (boyd Reference Boyd and Papacharissi2010), stands for the public, structured by networked technologies.

… [T]hey are simultaneously (1) the space constructed through networked technologies and (2) the imagined collective that emerges as a result of the intersection of people, technology, and practice … [T]he ways in which technology structures them introduces distinct affordances that shape how people engage with these environments. The properties of bits … introduce new possibilities for interaction. As a result, new dynamics emerge that shape participation. (boyd Reference Boyd and Papacharissi2010, 39)

In addition, boyd (Reference Boyd and Papacharissi2010, 42) highlights that ‘Networked publics are not just publics networked together, but they are publics that have been transformed by networked media, its properties, and its potential.’ boyd (Reference Boyd and Papacharissi2010, 53) claims that attention becomes the main commodity for users who function both consumers and producers, and so have agency within the attention economy. Finally, she focuses on internet and social media affordances, mainly how they are structured and shaped for users’ usage. Bucher and Helmond (Reference Bucher, Helmond, Burgess, Marwick and Poell2018) elaborate on the affordance concept and its employment in scholarship in even more detail. Their observations appear important for understanding Twitter's affordances and the methodological part of this research.

As Hoskins became a pioneer in talking about digital technology in the memory studies realm, in parallel, social movement scholars acknowledged the role of social media in their field. Exploring media's contribution to social movements, Bennett and Segerberg (Reference Bennett and Segerberg2012) distinguish the logic of well-known collective action and less familiar connective action. They conclude that connective action has a different logic, so a classical model of collective action analysis cannot be copied in connective action research. While collective action is based on public good and common interest, connective action counts on networked publics (boyd Reference Boyd and Papacharissi2010), which are decentralised and connected by personal interest. Authors agree that digital media changed organisational aspects of social movements and may reduce some logistical costs; however, it did not ‘change the core dynamics of the action’ (Bennett and Segerberg Reference Bennett and Segerberg2012, 739). They call for researching connective action in better detail, and Poell and van Dijck (Reference Poell, van Dijck, Burgess, Marwick and Poell2018) continue exploring the relationship between social media and social movements. Poell and van Dijck (Reference Poell, van Dijck, Burgess, Marwick and Poell2018) note that social media activities only accompany protest movements. There is no clear divide between online and offline activism: ‘[P]rotest simultaneously unfolds on the ground and online’ (Poell and van Dijck Reference Poell, van Dijck, Burgess, Marwick and Poell2018, 547) as digital technologies become integral to our lives. Most importantly, the authors remark that social media platforms pursue commercial purposes rather than serving as a fertile ground for civic movements. Conversely, Poell and van Dijck (Reference Poell, van Dijck, Burgess, Marwick and Poell2018) highlight that social media platforms can disrupt activists and even handle sensitive information to governments. Thus, social media becomes a field where different conflicts of interest crash.

This section will discuss the literature on memory activism and how digital media has changed it. Jelin's (Reference Jelin2003) monograph focuses on South American societies that struggle to deal with the violent past of military dictatorships and overcome settled silences. Thus, she defines memory as labour: ‘As a distinctive feature of the human condition, work is what puts the individual and society in an active and productive position.’ (Jelin Reference Jelin2003, 23). Also, the book discusses the essence of memory, common failures to cope with injustice and traumatic pasts, and the ways politics employ memories for their purposes. Another essential contribution to the evolving memory activism subfield is Memory Activism: Reimagining the Past for the Future in Israel-Palestine by Gutman (Reference Gutman2017). This study focuses on the efforts of bringing forward Nakba commemoration and Palestinian narrative, swept under the carpet by the hegemonic Israeli state. At the same time, Gutman (Reference Gutman2017) fills the gap to indicate what a memory activist is and who is not, becoming a pioneer in defining memory activism as ‘the strategic commemoration of contested past outside state channels to influence public debate and policy. Memory activists use memory practices and cultural repertoires as means for political ends, often (but not always) in the service of reconciliation and democratic politics’ (Gutman Reference Gutman2017, 1–2). Soon after, Gutman and Wüstenberg (Reference Gutman and Wüstenberg2021) developed a typology for comparative research on memory activists which I apply in this paper. Finally, Rigney (Reference Rigney2018) suggests combining social movements with memory by conceptualising the memory-activism nexus, categorised into memory activism, memory of activism, and memory in activism. She believes combining (traumatic) memory with hope for the future could lead to positive societal changes while sticking to the past fails to deal with emerging challenges. Her concept theoretically enriches the analysis of tweets, for example, as it provides a way to critically examine how memory and activism are entangled in social media content.

Using Rigney's (Reference Rigney2018) memory-activism nexus, Orli Fridman developed a solid monograph, Memory Activism and Digital Practices After Conflict: Unwanted Memories (Reference Fridman2022). Fridman also coined the notion of #hashtag #memoryactivism (Reference Fridman and Fridman2019), referring to hashtags usage on social media to commemorate a disputed history. Hashtags play an important role in Twitter's communication: they transform conversations into easily accessible and notable discourses, form communities, and have the potential to recontextualise something and call for action (Bennett Reference Bennett and Flick2022, 894–896). In the case of memory activism, hashtags serve as a memory tool, which helps to organise and share information about the past. As Fridman (Reference Fridman2022, 134) claims, ‘ … [hashtags] bring the unspoken to the surface, voicing what has been repressed, silenced, and denied in mnemonic struggles.’ This online practice generates an alternative space for remembrance to share and spread alternative perspectives on a contentious past and injustices, particularly in the context of (post-)conflict. #Hashtag #memoryactivism aims to promote alternative forms of knowledge and disseminate information (often counter-memories) about contested histories within societies.

Recently, a team of scholars including Gutman, Wüstenberg, Rigney, and Fridman inspired by practitioners like Šehović released The Routledge Handbook of Memory Activism (Gutman et al. Reference Gutman, Wüstenberg, Dekel, Murphy, Nienass, Wawrzyniak and Whigham2023). This handbook established memory activism's position as a memory studies subfield and suggested a new analytical framework for researchers and activists. Also, Fridman (Reference Fridman, Gutman, Wüstenberg, Dekel, Murphy, Nienass, Wawrzyniak and Whigham2023) and Fridman and Gensburger (Reference Fridman, Gensburger, Gutman, Wüstenberg, Dekel, Murphy, Nienass, Wawrzyniak and Whigham2023) thoroughly set up her memory activism study framework and main statement here.

Existing scholarship of (Hashtag) memory activism in post-Yugoslav space

Fridman's research bridges alternative commemorative practices and memory activism in the post-Yugoslav context. Living in Belgrade for quite some years, she observed and participated in various bottom-up initiatives in Serbia. First, Fridman (Reference Fridman2015) released an article on alternative calendars and memory work in Serbia, highlighting the Srebrenica commemoration in Belgrade. In another article, Fridman and Hercigonja (Reference Fridman and Hercigonja2017) analyse anti-government protests in the context of memory politics of the 1990s in Serbia. Fridman's article from 2020 deals with the peace formation coming from bottom-up initiatives as she explores the ‘Mirëdita, dobar dan’ festival that brings artists, activists, and youth from Kosovo and Serbia together as an alternative to everyday nationalism (Fridman Reference Fridman2020). Together with Katarina Ristić, Fridman contributed to one of the newest theoretical and empirical works from the memory studies field Agency in Transnational Memory Politics (Wüstenberg and Sierp Reference Wüstenberg and Sierp2020). Their chapter ‘Online Transnational Memory Activism and Commemoration’ (Fridman and Ristić Reference Fridman, Ristić, Wüstenberg and Sierp2020) focused on White Armband Day (bcs. Dan bijelih traka) on-site and online commemoration that, from a local and regional level, became a transnational commemorative event. In her monograph, besides #WhiteArmBandDay, Fridman (Reference Fridman2022) explores other initiatives like #Sedamhiljada (#Seventhousand to commemorate 20th anniversary of Srebrenica in Serbia), #NisuNašiHeroji (#NotOurHerous to condemn the ICTY convicts that become received as heroes and celebrities in the region of memory: Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Kosovo) and #JesteSeDesilo (#ItDidHappen to fight hegemonic narrative of Serbia, claiming that there was no war in Serbia). Although Fridman mainly focuses on Serbian case(s), her works remain crucial for my research and the region of memory (activism): the post-Yugoslav space.

Methodology to explore the usage of #ŠtoTeNema and research limits

Twitter as a platform of choice

Research confirms that Twitter has a relatively small amount of users (Marwick Reference Marwick, Weller, Mahrt, Burgess and Bruns2013, 119; Bennett Reference Bennett and Flick2022, 886) compared to Facebook, which managed to include all the demographic groups (Russmann Reference Russmann and Flick2022, 851). While Facebook involves the more regular people, Twitter remains an allocated platform for political issues and grassroots movements. Bennett (Reference Bennett and Flick2022, 886) distinguishes ongoing scholarly debates about whether Twitter remains an elitist platform that helps to communicate a specific agenda to the general public or whether Twitter empowers individuals to participate in public discussion and concludes that it has interactive potential. Also, one should remember that not everyone has access to the Internet (Marwick Reference Marwick, Weller, Mahrt, Burgess and Bruns2013, 119); hence, the processes on Twitter should not be treated as the reflection of offline society in the digital domain (Stegmeier et al. Reference Stegmeier, Schünemann, Müller, Becker, Steiger, Stier and Scholz2019). Nevertheless, ‘[Twitter] has become a key space for digital public discussion and, as such, can be thought of as a space for public sphere communication’ (Bennett Reference Bennett and Flick2022, 886). Accordingly, I chose Twitter's platform for this research.

Facebook's #ŠtoTeNema feed shows even more dynamic user interaction as this medium is more prevalent in the Balkans. However, because of Facebook's privacy regulations and its purpose of being more private, I believe Twitter's feed exhibits more integrity than Facebook's. In addition, the economy of tweets enables the researcher to collect and analyse a more extensive data set. Instagram may be an exciting choice; however, as ŠTO TE NEMA's posts dominate the feed, I narrowed my research down to Twitter, which exposes higher interaction.

Methodology and its limits

This research leans on #hashtag #memoryactivism (Fridman Reference Fridman2022, 133) study framework and multimodal discourse analysis (MMDA) to explore the collected tweets. MMDA (Kress Reference Kress, Gee and Handford2012) allows for the inspection of various modes within a tweet (texts, hashtags, visuals, hyperlinks, and metadata) and the meaning they constitute together (and separately). Discourse analysis highly considers the agency (Vinogradnaitė Reference Vinogradnaitė2006), which matters when exploring who uses #ŠtoTeNema (Gutman and Wüstenberg Reference Gutman and Wüstenberg2021) on Twitter. Also, I conduct some basic quantitative actions in this research (i.e., turning tweets, categories, and words into numbers and searching for supplementary meanings in quantitative processing).

I started the analysis by collecting the ‘latest tweets’ through the regular user interface of the Twitter platform, which helped me to see the data as a regular end-user and get to know it well. At the same time, I created a collection on Citavi software, and I stored up all (i.e., 271) tweets from 2012 to 2022,Footnote 15 including retweets and replies, that used #ŠtoTeNema or #StoTeNema (as Twitter recognises both as the same hashtag). Indeed, 271 tweets across ten years is a minimal amount of data. Plus, 85 tweets (one-third of the entire dataset) originate from the accounts directly connected with the ŠTO TE NEMA (@StoTeNema (40 tweets) and Post-Conflict Research Center (PCRC/@PCRCBiH) (45 tweets), which closely collaborate with ŠTO TE NEMA since 2020). Indeed, many more tweets are connected with the ŠTO TE NEMA initiative, but I limited myself to those using #ŠtoTeNema. I understand that ‘the majority of tweets do not include hashtags’ (Marwick Reference Marwick, Weller, Mahrt, Burgess and Bruns2013), so many tweets dropped out of this research. However, focusing on the tweets embracing #ŠtoTeNema helped me naturally limit this research. A total of 271 tweets become a doable number to deal with all the entire data rather than conducting a selection. Also, collecting all #ŠtoTeNema tweets gives a clearer picture of the online memory activism initiative.

To organise the data, I coded it (Kuckartz Reference Kuckartz2014). Some basic coding (like attributing the themes and main keywords) was done immediately after importing the tweets on Citavi. The coding process continued after I finished collecting the data and observed the emerging text trends, spotting more meanings. Also, I indicated different languages used in tweets and distinguished what kind of agent (person/organisation) was tweeting. Instead of using software to download the tweets, I print-screened, saved them, and conducted manual coding. This process allowed me to observe the patterns and repetitions and explore the meanings.

The most significant disadvantage of this research may be that I did not conduct digital ethnography, following the hashtag for all these years once the hashtag emerged. Instead, I collected the data between December 2022 and January 2023. Therefore, I was dealing with old tweets; some became unavailable as they had been deleted and hidden for privacy or other reasons. For example, the Twitter Analytics function was no longer available, stating that ‘view counts are not available.’ Also, I lost an opportunity to observe the opposition (i.e., the behaviour of genocide deniers and glorifiers) because some comments were probably reported to Twitter as hate speech over time.

Lastly, I ‘de-identify’ the data as much as possible to protect the identity of Twitter users. However, the accounts of NGOs and various organisations/initiatives (including @StoTeNema and @PCRCBiH) and verified accounts (like @BosnianHistory) remain unhidden.

Results after exploring #ŠtoTeNema on Twitter

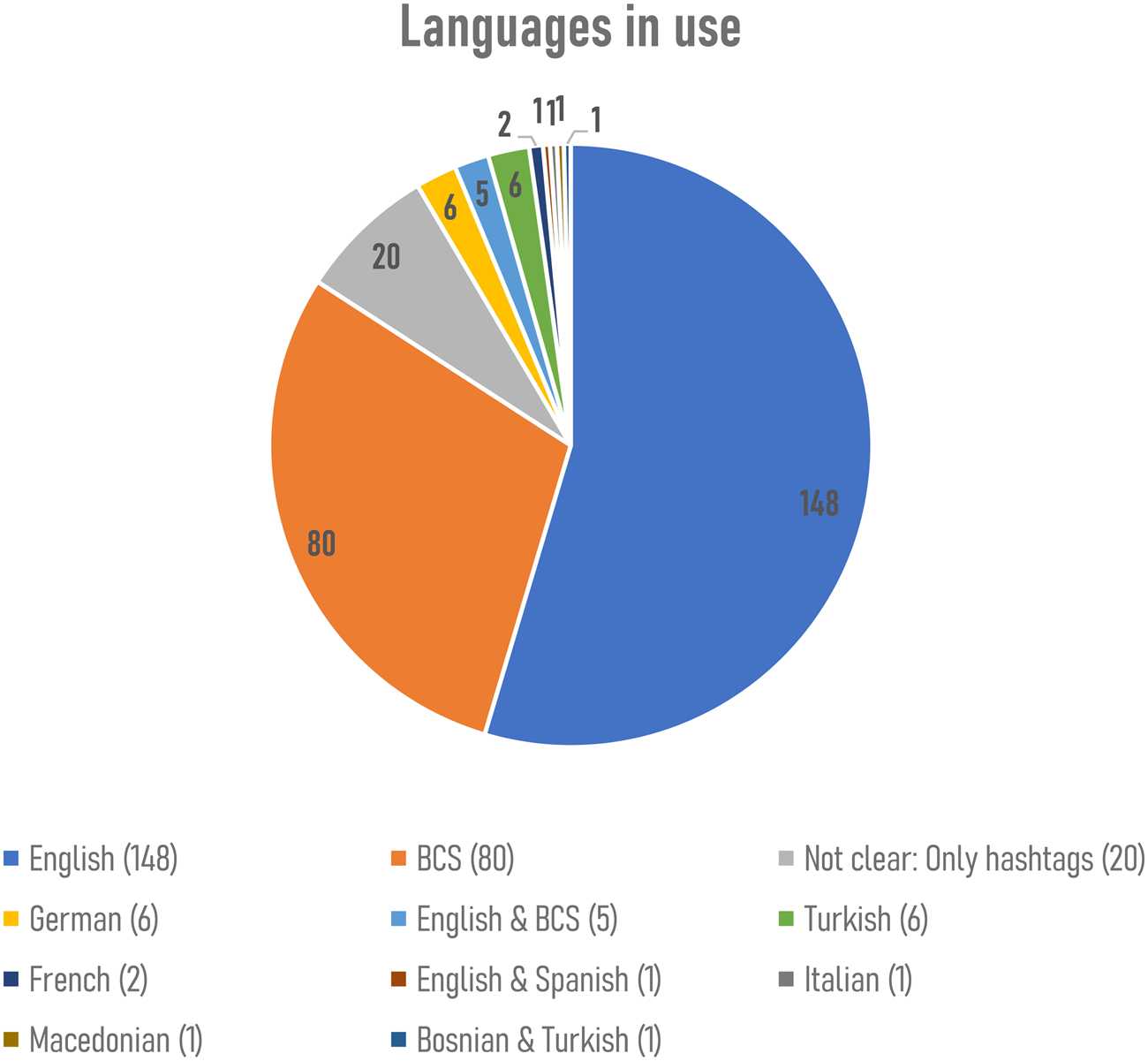

Tweets about #ŠtoTeNema appear exclusively visual and multimodal: out of 271 tweets, 163 included picture(s), 18 were published with a video,Footnote 16 11 shared a hyperlink to access some article that was transformed into a visual on the Twitter feed,Footnote 17 and 1 contained a link to a podcast. One may observe that this kind of visuality and multimodality intensified during the global pandemic in 2020. The second characteristic feature is the variety of embraced languages (Figure 1). The majority of tweets (148) were typed in English. Therefore, they primarily addressed the international community. Indeed, the ‘top tweets’ were mainly in English. The second most popular language was BCS (80 tweets), addressing the region. The third category of 20 tweets did not relate to any particular language as they applied only hashtags that often went together with pictures. However, sometimes such tweets additionally included numbers (e.g., ‘#25 #StoTeNema,’ ‘#StoTeNema #Srebrenica,’ ‘#StoTeNema 11.07.1995.’) to commemorate the genocide's anniversary or the date. Tweets appear multilingual and transnational: among other language groups, there is German (6), English mixed with BCS (5), Turkish (6), French (2); English mixed with Spanish (1), BCS mixed with Turkish (1), Italian (1), and Macedonian (1).

Figure 1. Languages in use.

The dynamics of tweets posted through the years (Figure 2) are also worth discussing. #ŠtoTeNema was tweeted for the first time by GBDi (Young Bosnians Association in Istanbul, @GBDistanbul) on 11 July 2012, when the monument was placed in Istanbul, and before the official @StoTeNema account on Twitter was even created. According to Twitter, Šehović launched the @StoTeNema in 2013. However, it remained inactive for some years, with the first tweet appearing only on 11 July 2015. At that time, social media was not a priority for ŠTO TE NEMA due to a lack of social media strategy, a defined discourse, and a clear concept resulting from limited capacity and resources. Nevertheless, ŠTO TE NEMA still formed a particular message and image, as I will explain later.

Figure 2. Chronological distribution of the collected tweets.

@StoTeNema's first tweet did not include #ŠtoTeNema; however, the second tweet on the same day did. 11 July 2015 marked the 20th anniversary of the genocide and the 10th anniversary of ŠTO TE NEMA. The 25th genocide anniversary on 11 July 2020 became a particular hashtag, #Srebrenica25 (81 tweets), together with #StoTeNema2020 (20) and #25 (1). Throughout the period (2012-2022), #ŠtoTeNema was always trending in July: 203 out of all 271 tweets were delivered that particular month. Tweeting intensified around 11 July, Srebrenica Genocide Day.

Nevertheless, the most relevant shift to commemorate online in addition to an on-site campaign became very important during the global pandemic (2020). Despite various restrictions, people wanted to engage in commemoration from home, and social media became the most accessible space to do that. Thus, @StoTeNema Twitter account was the most active in 2020. In fact, almost half of the collected tweets were generated in 2020 (129). In 2020 summer, ŠTO TE NEMA and its partner PCRC launched a bilingual (English-BCS) social media campaign, Fildžani stories, on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram. They shared stories of collected coffee cups – who and why they donated the cup(s), what this initiative meant to the benefactor(s), and personal quotes. Fildžani stories have received much attention and appeared to be a successful effort.

Who did (re-)tweet #ŠtoTeNema?

I explored and grouped who has (re-)tweeted #ŠtoTeNema to get to know this networked public (boyd Reference Boyd and Papacharissi2010) on Twitter. Individuals tweeted the majority of tweets (134). The group consists of eight journalists, three foreign photographers, eight scholars/researchers, six activist citizens who do not share much information, four individuals working at PCRC, three Balkan enthusiasts from Zürich, three Balkan diaspora members, three micro-influencers,Footnote 18 one person leading a podcast,Footnote 19 one activist who clearly identifies as such, one family physician and fifteen other individuals, who appeared as a very mixed sub-group. The second biggest group belongs to organisers, as 85 tweets came from @StoTeNema's and @PCRCBiH's official accounts. The rest of the groups appear to be much smaller: 16 tweets posted from non-profit organisations, including diaspora organisations, 11 tweets released from news agencies, 11 tweets tweeted by the eleven authorities, such as diplomats/government officials from outside the region (5), diplomats from the region, including Bosnia, Croatia, and Serbia (4), politicians from Serbia (1) and Bosnia (1); 4 tweets came from museum accounts, 2 tweets from @BosnianHistory that appears as a macro-influencer (46.5 K Followers); 2 tweets came from 2 accounts that were hard to group and 1 tweet from the sponsor account. Therefore, though Twitter aims to move towards a more inclusive sphere of political communication, the most active users remain societal and political elites (Stegmeier et al. Reference Stegmeier, Schünemann, Müller, Becker, Steiger, Stier and Scholz2019, 289), and this research only confirms that.

Regarding tweeting, one must remember that Twitter limits users to 280 characters per tweet.Footnote 20 This limit therefore shapes and constricts tweets by @StoTeNema and @PCRCBiH. Indeed, ŠTO TE NEMA communication is very soft: it does not embrace verbs common for ‘never again’ narrative, such as ‘have,’ ‘must,’ or ‘should.’ ŠTO TE NEMA does not dictate what to do; it only informs and raises awareness. Nevertheless, ŠTO TE NEMA forms and operates a particular pattern of aesthetics (fildžani pictures), the anti-genocide narrative, vocabulary of inclusivity, anti-hatred and peace, values of integrity, diversity, understanding, involvement, and humanity, as well as specific hashtags for its audiences. For instance, the hashtags that ŠTO TE NEMA embraced (e.g., #StoTeNema/#ŠtoTeNema, #Srebrenica25, #Srebrenica, #SrebrenicaGenocide, #AidaŠehović, #bosniangenocide) became widely spread among audiences who became memory agents. Some users embraced only hashtags in the text section and enriched their message with the picture; it appeared to be standard practice in this research. However, sometimes it seemed that some hashtags did not have anything to do with the ŠTO TE NEMA initiative and lived their separate lives.

The typology of memory activists (Gutman and Wüstenberg Reference Gutman and Wüstenberg2021) indicates ŠTO TE NEMA team and people using #ŠtoTeNema as entangled agents and pluralists, mostly seeing the past as an ended process. Their relational roles in realised interventions define them as entangled agents. ŠTO TE NEMA team is not directly related to the Srebrenica genocide; however, they come from Bosnia and were affected by the war (i.e., ‘see themselves connected to their ‘heritage’ (Gutman and Wüstenberg Reference Gutman and Wüstenberg2021), thus bear responsibility to talk about it and inform the world. The same goes for their followers who embrace #ŠtoTeNema: only one tweet came from the victim (a young person whose uncle was killed during the genocide), and all the others seem not to be directly connected with the genocide. However, as mentioned above, they follow the tone set by ŠTO TE NEMA, aiming to raise awareness about what happened. I see this agency as pluralist because ŠTO TE NEMA does not push the only truth (Karabegović Reference Karabegović2014). Instead, it talks about the genocide and fights its denial, but in a personalised way, as every fildžan, every victim has his or her story. Therefore, this approach opens up space for multiple perspectives but does not provide an opportunity to debate whether the genocide happened. For ŠTO TE NEMA, the genocide occurred in the past, and it calls for a better, more inclusive future with informed citizens. Most of the entangled agents embrace and disseminate this approach on Twitter.

Interactions and metadata

Unrivalled @BosnianHistory's (46.5 K Followers) tweets were the most impactful. Unfortunately, the tweets were too old to see the reach. However, a tweet from July 2020 (Figure 3) collected 549 retweets, 27 quote tweets, and 1,674 likes and another tweet from July 2022 (Figure 4), 804 retweets, 11 quote tweets, and 2,120 likes. These tweets reveal diverse interactions. Most people give their respects to the victims (they write a short commemorative text, type a sad emoji with tears, praying hands, red or green (referring to Islam) heart or heartbroken emoji, and invite people not to forget and remember the genocide). There are a few comments on genocide denial (including offensive glorifying discourse, aims to highlight the suffering of Serbs, and victim blaming). Some replies or retweets express a multidirectional approach (Rothberg Reference Rothberg2009): While commemorating the Srebrenica genocide online, they also raise awareness of other crimes that happened in different places of the world, often seeking genocide recognition status and sharing about the sufferings in the home countries. Ten tweets typed by individuals (on-site participants, activist citizens, and politicians) gained quite a lot of attention, collecting more than 50 likes (up to 384). These likes, retweets, and replies mainly indicate the support from the networked public (boyd Reference Boyd and Papacharissi2010), which contributes to virtual mourning. Nevertheless, those personal tweets attracted replies from deniers. For example, one individual shared a quasi-academic article that downplayed the gravity of the crime and instead highlighted the suffering of Bosnian Serb victims in Srebrenica. After a Serbian politician shared an article accusing the Serbian authorities of denying the genocide, demanding responsibility and aiming to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the genocide, several individuals either expressed gratitude or denied the genocide in various manners. They raised issues about unacknowledged Serbian victims and NATO bombing, waived their responsibility, called her a liar or traitor, and shamed her. Thus, users were divided. It would be interesting to see the quantity of #ŠtoTeNema tweets that had originated in Serbia. My observations suggest that not too many, but some did, and those tweets were quite powerful. For example, a tweet compared two images: a photo of a young Serbian politician, Aleksandar Vucić (president since 2017), placing a ‘Ratko Mladić Boulevard’ sticker on a wall in 2007 and a picture of ŠTO TE NEMA's fildžans. However, additional geolocation and network analysis should be conducted to learn more about Serbian users and determine the effectiveness of #ŠtoTeNema online commemorations in creating connections and educating people.

Figure 3. @BosnianHistory tweet from 11 July 2020.

Figure 4. @BosnianHistory tweet from 11 July 2022.

The tweets that did not mention ŠTO TE NEMA or Srebrenica, but included the #ŠtoTeNema hashtag, did not receive significant engagement.

Meaning-making on Twitter

Undoubtedly, most tweets (225) are directly related to the ŠTO TE NEMA initiative and were part of the hashtag memory activism campaign (Figure 5). The individuals who posted them were frequently linked to ŠTO TE NEMA, either directly or indirectly, so these tweets were barely random. Therefore, they mainly followed the tone set by @StoTeNema: commemorated anniversaries, honoured victims, raised awareness about the Srebrenica genocide, encouraged to participate on-site, asked to donate to support the initiative (in particular, film production), and shared ŠTO TE NEMA fildžani pictures. Besides that, Twitter users declared some additional meanings not necessarily directly promoted by @StoTeNema: they claimed ‘never again’ or/and ‘never forget,’ called for justice or protection, refused hatred, highlighted the importance of such art acts or appreciated Šehović's work, expressed gratitude for an opportunity to participate in the action on-site. However, these meanings only complemented the ŠTO TE NEMA narrative.

Figure 5. #ŠtoTeNema thematic distribution on Twitter.

Probably the most interesting group is the 20 tweets, which use #ŠtoTeNema to commemorate Srebrenica but do not relate to Šehović's initiative.Footnote 21 They mainly followed the ŠTO TE NEMA narrative described in the first paragraph; however, at the same time, they added some new content. In one of the cases, a user with more than 10k followers uploaded a drawing of the Mothers of Srebrenica surrounding a green coffin. Over time, this composition developed into a Remembering Srebrenica Footnote 22 logo (the white flower with the green centre). Indeed, another tweet shares the Remembering Srebrenica logo when embracing #ŠtoTeNema. Although the Remembering Srebrenica initiative is unrelated to ŠTO TE NEMA, some people on Twitter bring them together, as both initiatives remember the same event. Another interesting example is a tweet sharing an image of a blue butterfly. Apparently, the blue butterfly (lat. Polyommatus icarus) helped scientists to find the mass gravesFootnote 23 and bring the first evidence to ICTY (the Independent 2004). The other tweet shared the drawing of a Dutch-United Nations peacekeeper ignoring the Srebrenica genocide. For decades, the Dutch government did not recognise their failure to protect the Srebrenica ‘safe area’ and ignored the fact of participating in the separation of Bosniak men and boys in Potočari (van den Berg and Hoondert Reference van den Berg and Hoondert2020; Žarkov Reference Žarkov, Abazović and Velikonja2014). However, it seems that the process moved forward as Dutch authorities finally apologised to relatives of the victims for the first time in 2022 (Al Jazeera 2022). Another example is the tweet in Turkish, which mourns the victims of the Srebrenica genocide but does not include any ŠTO TE NEMA symbols or attributes. The same works for the tweet of the British Embassy Podgorica: it shares a video that presents the facts on the Srebrenica tragedy but does not touch upon the ŠTO TE NEMA project. The last exciting example is two tweets exposing their coffee cups, which are not fildžani, and thus expose different aesthetics than ŠTO TE NEMA's. One tweet, shared by a baking enthusiast, portrays a coffee cup with two white violas on its saucer. The intended meaning behind the tweet is unclear, but as it appeared on 11 July, one could assume that it relied upon ŠTO TE NEMA. The other user shared a picture of two large coffee cups (of him and his partner) and expressed the hope that such atrocities would never occur again. In a thread, he also remarks on the importance of the coffee ritual in Bosnia, claiming that women from Srebrenica often miss drinking coffee with their husbands. These two tweets confirm that the ŠTO TE NEMA storytelling captured the audience's attention as they incorporated the content into their coffee rituals.

The idea of ŠTO TE NEMA is that the coffee remains undrunk while Twitter users prepare it for consumption. However, Bosnian coffee culture lies in the connections between people and companionship, and ŠTO TE NEMA aims to address the absence of these values after a violent conflict. To conclude, the group discussed in the previous paragraph only enriches the ŠTO TE NEMA content by adding new details and facts to inform the Twitter community about the Srebrenica genocide. These 20 tweets prove that #ŠtoTeNema became a way to commemorate the genocide. Even if the visuals do not include fildžani, #ŠtoTeNema relates to Srebrenica remembrance. Content recycling, editing, and mixing appear to be a widespread practice in digital culture, as the research on memes and memetic activism (Boudana et al. Reference Boudana, Frosh and Cohen2017; Castaño Díaz Reference Castaño Díaz2013; Shifman Reference Shifman2015) shows.Footnote 24 This research's findings only confirm that #ŠtoTeNema connected various visual symbols related to commemorating the Srebrenica genocide and incorporated them within a unified meaning universe. The white flower with the green centre, blue butterfly, and Dutch peacekeepers each added a new layer of meaning (mourning, search for justice, and responsibility), broadening the scope and contributing additional themes to the original initiative. Consequently, #ŠtoTeNema became a remarkable instance of participatory and interactive memory activism.Footnote 25

Another group of seven tweets admired the Što te nema song (which inspired the project). Indeed, Što te nema is first known as the Bosnian folk song, sevdalinka (love song), written by a famous Mostar poet, Aleksa Šantić,Footnote 26 in 1897. In 1981, Što te nema song was performed by a Bosnian singer, Jadranka StojakovićFootnote 27 and became extremely popular in Yugoslavia. In a tweet and retweet of the same person, the themes of sevdalinka admiration and Srebrenica entangled: the tweet includes a video of an opera singer, Aida Čorbadžić, singing Što te nema, as well as the hashtags both appreciating the voice and remembering Srebrenica. Also, the video includes the Remembering Srebrenica logo. In this case, the tweet does not relate to Šehović's initiative but to commemoration and mourning. However, some other tweets respond to TV song competitions and support their favourite singers; therefore, they have nothing to do with Srebrenica.

The rest of the tweets reveal different themes, not connected with ŠTO TE NEMA. Seven tweets were associated with some entertainment or/and inside jokes. For example, somebody was missing at the party, so a person tagged somebody with the hashtag #ŠtoTeNema, meaning why aren‘t you with us? The other five tweets acknowledge missing somebody (including the love of her life). Indeed, Šantić dedicated his poem to the deep suffering of love's absence. Finally, the last four tweets provided no context and were impossible to interpret.

Discussion

Concerning memory studies

When expanding Rigney's (Reference Rigney2018) memory-activism nexus, all three components play an essential role in this research. Memory activism stands for Šehović's and her team's work for the future; memory of activism marks earlier struggles for recognition by such organisations as Mothers of Srebrenica, Mothers of the Enclaves of Srebrenica and Žepa, Women of Srebrenica, Women of Podrinje, and Women in Black from Belgrade and memory in activism unfolds how earlier movements inform ŠTO TE NEMA (for example, Women of Srebrenica inspired and supported Šehović's idea, which developed into a long-term project). Also, this nexus highlights the importance of gender roles in Srebrenica memory activism. It is easy to notice that women's organisations did the main memory work, considering that most men were killed during the genocide. Then ŠTO TE NEMA and Post-Conflict Research Center (PCRC) are women-led non-government organisations. In addition, individual tweets reveal that all foreign diplomats who employed #ŠtoTeNema were women. In contrast, local/regional politicians, diplomats, and journalists are equally gender-divided. Unrivalled, all activist citizens (as I identified) and all the scholars (except one) were women. Thus, Srebrenica's (voluntary) memory activism has a woman's face, while the official Srebrenica memory keeper – Srebrenica-Potočari Memorial Center – is led by men.

ŠTO TE NEMA contributed to the memoryscapes of the region and beyond in different ways. Initially, it had a solid foundation set by the abovementioned organisations, which was necessary for further development. In particular, Women of Srebrenica encouraged Šehović to start collecting the cups and performing in 2006, while many people, including her family, were sceptical about the idea (Whigham Reference Whigham, Gutman, Wüstenberg, Dekel, Murphy, Nienass, Wawrzyniak and Whigham2023). Since the beginning, ŠTO TE NEMA has been an inclusive initiative that invited everyone, regardless of their background and identity, to join the act of remembrance. Šehović refused any state or religious symbols as she wanted to create something universal and accessible for everyone, regardless of where they come from. Digital mourning took over the same values; therefore, Bosnians commemorated with people from different countries who connected with the project's concept. While Dan bijelih traka demonstrated the community's transformation from a local/regional level into a transnational commemorative event (Fridman and Ristić Reference Fridman, Ristić, Wüstenberg and Sierp2020), ŠTO TE NEMA was intentionally created to be both local/regional and transnational. Šehović invented a language to approach people worldwide and witness the genocide by outlining the absence of a dear person one lost. That set the participants closer to people who lost entire families and raised empathy. In this way, ŠTO TE NEMA informed the global community about the Srebrenica genocide, sought equal recognition for the victims, and aimed to prevent similar atrocities.

Concerning memory studies + Twitter's affordances

I want to challenge Fridman's (Reference Fridman, Gutman, Wüstenberg, Dekel, Murphy, Nienass, Wawrzyniak and Whigham2023) statements about hashtag genealogies based on Hoskin's (Reference Hoskins and Hoskins2018a) idea that hashtags are inherently archival. First, Twitter does not perform the role of an archive, and the tweets can disappear at any moment. Archives have a long-term retention characteristic, while social media appears ephemeral as Twitter's administration and end-users may delete the data at any time. In turn, tweets could be edited and manipulated. In October 2023, I checked the #ŠtoTeNema hashtag on Twitter and could not find all the tweets I collected ten months ago, possibly reflecting public reactions over Elon Musk's takeover of the platform. Second, even if tweets and threads appear liberated from traditional memory institutions, private companies own and entirely control them. Thus, users depend on the platform's constantly changing policies, including privacy, that prevent independent research. Third, Twitter limits access to metadata, which appears essential in archival work, making cataloguing and searching challenging or inaccessible. Finally, even if the users presume that Twitter works as a repository, it primarily serves commercial purposes. Social media design lacks organised structure, long-time preservation, and reliability.Footnote 28

When discussing interactions on Twitter (likes, retweets, and replies), one must consider how they are structured by Twitter's affordances and what they mean in the communication process. Rogers (Reference Rogers, Burgess, Marwick and Poell2018) claims that although different platforms (such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram) have similar buttons (ways to react), they should not be treated the same way. Until 2015, the ‘like’ button on Twitter was a ‘favourite’ button and indicated something people would like to return to later (Bucher and Helmond Reference Bucher, Helmond, Burgess, Marwick and Poell2018). Regarding digital mourning, pressing ‘like’ (even if it sounds odd) means expressing empathy and joining virtual commemoration. People who retweeted/reposted mourning tweets primarily wanted to spread the message about the genocide among their followers.

Regarding replies, I did not indicate any dialogues or discussions. The quotes/replies and retweets enable users to give their statements: they either commemorate or deny the genocide. This research suggests that when recognising the Srebrenica genocide, separate communities with different vocabulary prevail: people who deny it, glorify it, and acknowledge the genocide raise awareness and mourn. #ŠtoTeNema networked public belongs to the following category. In some cases, ŠTO TE NEMA left its ‘echo chamber’ as some tweets received counter-replies, and the mourning networked public met the networked public of deniers. Nevertheless, they remain highly divided (boyd Reference Boyd and Papacharissi2010): it is doubtful that someone will change their opinion or ‘side.’ However, this controversy may influence people who know little about Srebrenica and remain passively observing Twitter's feed rather than participating.

Social media platforms change the algorithms for commercial interest (Poell and van Dijck Reference Poell, van Dijck, Burgess, Marwick and Poell2018). Social media creates personalised bubbles by implementing the attention economy (boyd Reference Boyd and Papacharissi2010) system. If end-users used to see broader content on Twitter's feed in the past (Bucher and Helmond Reference Bucher, Helmond, Burgess, Marwick and Poell2018), now one can scroll through the feed made by algorithm (‘for you’) or check the tweets of people they follow. That makes raising acknowledgement of specific issues and addressing a broader audience hard, if not impossible. That is why political activism online ends up being unpaid digital labour and a lonely voice as agents lose the battle with the algorithm.Footnote 29 Still, Treré (Reference Treré and Meikle2018) research shows that Spanish activists managed to study the algorithm and utilise it to maximise their visibility on Twitter. Nonetheless, it requires considerable effort, and once platforms recognise that they have lost commercial interest, they may change the algorithm (Poell and van Dijck Reference Poell, van Dijck, Burgess, Marwick and Poell2018). Generally, the current algorithms tend to deepen polarisation in the local community and society, transforming the internet into a medium for disseminating propaganda (Treré Reference Treré and Meikle2018), conspiracy theories, fake information, and hate speech (Lewandowsky and Kozyreva Reference Lewandowsky and Kozyreva2022). For example, when one searches for Nož, žica, Srebrenica on Twitter, the platform shows many tweets that embrace this chauvinist motto. Twitter is becoming a far-right social network as Musk invited right-wing activists excluded from the platform to be back on the social network (Instagram 2023). Twitter claims to fight hate speech, but the platform disseminates it rather than does anything to prevent it. If the platform does not change, this article may be the last fling on democratic memory activism on the Twitter (now X) platform.

Conclusions

ŠTO TE NEMA demonstrates that artists and activists (or simply artivists) have assumed a key role in acknowledging war crimes, coming to terms with the past, and working towards post-war peacebuilding. Using the art language, Šehović changed the memory climate of the Srebrenica genocide, meaning that the victimhood narrative has shifted towards a universal story of absence that is easier to relate to for any person. Indeed, the memory work done in the past by other organisations and the fact that 28 years have passed after the genocide contributed to this shift as well. Hence, Srebrenica remembrance has entered a new phase.

The message sent by ŠTO TE NEMA organisers was mainly received in the same way it was encoded. People who engaged in disseminating information about the Srebrenica genocide and contributed to virtual mourning became memory agents on Twitter. These memory agents were mainly human rights activists, including journalists, scholars, NGO employees, and supportive institutions, with occasional contributions from the general public. Most users who embraced #ŠtoTeNema followed the pattern of @StoTeNema and communicated the same message to their circles.

In some cases, the message was slightly changed or was complimented by additional facts and information about the Srebrenica genocide. Only rarely hashtag #ŠtoTeNema was used for some other purposes, not connected with the movement. That confirms that #ŠtoTeNema became a sort of movement which managed to set its statement through various modes, such as moving text, attractive images, and adjustable hashtags. Moreover, ŠTO TE NEMA became the unofficial face of Srebrenica remembrance in digital mourning practises.

In its own time, #ŠtoTeNema enabled the dissemination of knowledge and raised global awareness about the genocide online. Indeed, it was not as viral as #BlackLivesMatter or #MeToo but became imperative during the peak of the worldwide pandemic (2020). ŠTO TE NEMA included everyone willing to follow the initiative and mourn virtually. At the same time, #ŠtoTeNema enabled the audience to share information about the atrocities and the 25th anniversary of the Srebrenica genocide online, which was the only interaction space then.

This research highlights the main features of digital commemoration via #ŠtoTeNema. It is multimodal, transnational, and driven by memory activism, specifically the strategic activism of Šehović. The commemoration has been amplified by the pandemic. Building on previous research (e.g. #WhiteArmBandDay), this article demonstrates that digital commemorations, which may appear spontaneous, actually rely on strategic activism by individuals, whether they are NGOs or artists. This challenges the notion that digital space is inherently open and independent of structures.Footnote 30

After 18 years of experience, ŠTO TE NEMA is in transition today. Recently, ŠTO TE NEMA became a newly formed non-governmental organisation in Bosnia and incorporated a non-profit organisation in the United States of America. Therefore, it firmly continues to raise awareness about mass atrocities and contribute to transnational moral orders and memory politics in Bosnia and abroad.

Data availability statement

Due to the nature of the research, ethical supporting data are unavailable.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to Dr James E. Baker for his exceptional proofreading and insightful suggestions. I also thank Aida Šehović for clarifying the facts concerning ŠTO TE NEMA. I am obliged to Dr Ivana Stepanović for her advice when working on this article. Most importantly, I express my gratitude to the anonymous reviewers; I thank them for their patience and constructive criticism that made this piece more solid and grounded in the existing literature on memory activism and social media affordances. Additionally, I would like to thank Bilge Akpulat for translating Turkish tweets for this research.

Disclosure statements

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Rimantė Jaugaitė (University of Bologna) is a PhD student in the Global Histories, Cultures, and Politics program to develop a project on the alternative commemorative practices and politics of mourning across post-Yugoslav space, with a particular focus on Srebrenica remembrance through coffee.