Introduction

In the footsteps of Michael Pearson, Kapil Raj, Sanjay Subrahmanyam and others who have analysed the impact of the movement of people and ideas during the so-called ‘Age of Commerce’,Footnote 1 a number of historians of medicine, including Mark Harrison, Pratik Chakrabarti and Suman Seth,Footnote 2 have demonstrated the intrinsic connection between colonial expansion and the development of medical knowledge. In Portuguese historiography, or that dealing with Portugal, Henrique Leitão, Palmira Costa, Amélia Polónia, Eugénia Rodrigues, Cristiana Bastos, Timothy Walker and Hugh CagleFootnote 3 have pointed out the importance of health care agents as cultural mediators and disseminators of science. This article will merely examine the role played by the crown and the physicians and surgeons that served it in some of the material circumstances surrounding the interactions, assimilations and exchanges of knowledge that gave rise to what has become known as ‘colonial medicine’.Footnote 4

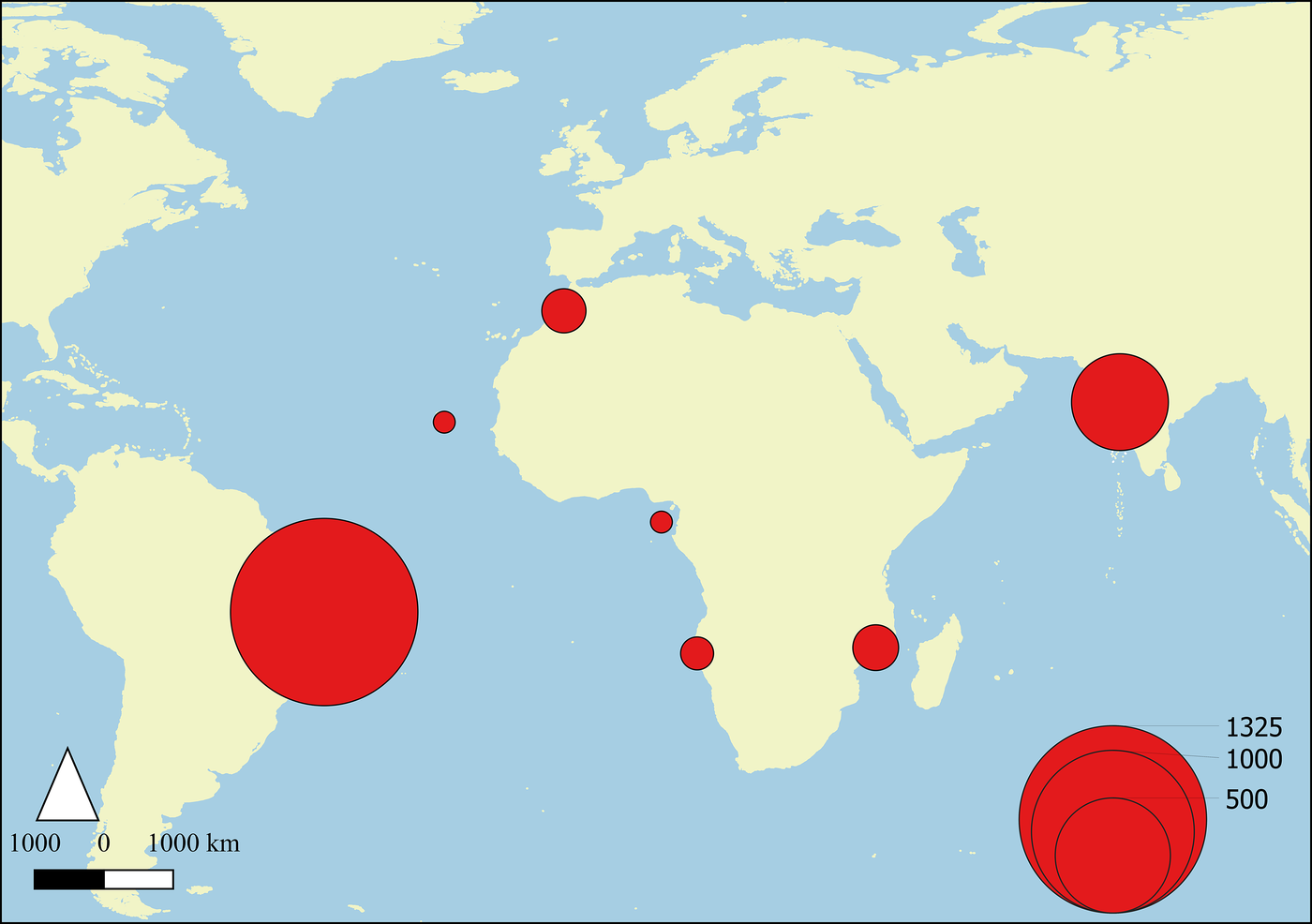

The empire in all its geographical extent and diversity will be the subject of this study (Figure 1), although the focus will linger slightly more on Goa, ‘the capital of the Portuguese Estado da Índia’,Footnote 5 due to the very specific features found there. The main documentary resource used is the information contained in 3548 nominal records on roughly 2000 ‘healers’ (curadores) who served in the colonies at some point in the sixteenth–eighteenth centuries,Footnote 6 together with countless other primary sources, most of them transcribed (and analysed) in the early twentieth century, but here examined in light of the latest research into this area in Portugal. The study does not include healers who left Portugal on their own account and/or became better known for their writing than for practising medicine in the service of the crown, as is the case of Garcia de Orta, the author of Coloquios dos simples e drogas e cousas medicinais da India (notes on the simples and drugs and materia medica of India), who is the subject of abundant specialist literature. It also excludes the religious orders (apart from a brief mention as royal hospital administrators), which developed their own health care and welfare schemes that sometimes complemented and sometimes competed with the crown’s.

Figure 1 (Colour online) Numbers of Portuguese health care professionals in the empire (1496–1826). Updated from Laurinda Abreu, ‘A institucionalização do saber médico e suas implicações sobre a rede de curadores oficiais na América portuguesa’, Revista Tempo, 24, 3 (2018), 494.

Health care practitioners in the empire: the early years

A central figure in the organisation of health care and welfare in Portugal was King Manuel I (1495–1521), whose role in setting up the misericórdia brotherhoods, increasing the number of health care professionals and regulating their training is particularly relevant in the context of this article. The misericórdias – lay brotherhoods governed by local elites that were dependent on and protected by the crown – were chosen by the king to implement central government’s new welfare policies. In 1510, he also began to entrust them with the administration of hospitals, which until then had been subject to a separate reform process. The first misericórdia was established in Lisbon in 1498; by the time of D. Manuel’s death in December 1521, there were 80 such organisations in Portugal and its empire, and at the beginning of the seventeenth century, there were over 300, all of them following a rule based on that of the Lisbon Misericórdia. In relation to health care professionals, D. Manuel reorganised and strengthened the powers of the chief surgeon (cirurgião-mor) – who was in charge of surgeons, barber-bloodletters, midwives and several other professions – and the chief physician (físico-mor), who had his own specific statute (regimento), issued in 1515 and amended to strengthen his powers in 1521, which regulated his work as an inspector of apothecaries’ shops and examiner of prospective apothecaries and physicians. These would-be physicians were almost always empirical surgeons, who could be granted full licences to practise (cartas de medicina, ‘medical licences’) or temporary ones (cartas para curar de medicina, ‘licences to treat with medicine’). The university saw the chief physician as a competitor affecting its recruitment of potential students and also accused him of endangering people’s health by leaving them at the mercy of the ‘ignorant and unqualified doctors’ that he licensed. By granting the chief physician the right to validate medical degrees obtained abroad, the 1515 statute increased his powers further, particularly after the university medical curriculum was reformed in the 1540s, making it one of the longest in Europe and leading Portuguese students to look for shorter degrees abroad. To make its course more attractive, the University of Coimbra (the only institution to train doctors in Portugal) not only benefited from a scheme of municipal-council-funded scholarships for medical students, established in 1568, but also persuaded the crown to reserve the main central and local government health care positions for its graduates, within the Regimento dos médicos e boticários (Physicians’ and Apothecaries’ Statute) of 7 February 1604.Footnote 7

This was the context in which Portuguese health care practitioners participated in the expansion of empire. Most of them sailed out with senior military officers and governors and later returned with them to Portugal.Footnote 8 In the colonies, the crown focused its attention on the forts where the explorers set up so-called hospitals, from São Jorge da Mina in present-day Ghana to the Estado da ÍndiaFootnote 9 (Cochin 1505, Cannanore 1506, Mozambique Island 1507 and Goa 1510Footnote 10), where they left a few medicines, at times surgeons and barber-bloodletters, and on rare occasions, physicians. The viceroys in India remarked that these buildings were solidly constructed (‘stone-built hospitals’), although time did not bear out that description: by the 1540s, the hospital in Cochin was ‘collapsing and rotting away’. In the same decade, medical care at the Diu hospital was being dispensed by ‘nurses’ who were no more than totally untrained servants or members of religious orders, as Friar Paulo de Santarém wrote to the king at the end of September 1546 in his request for a pharmacy and ‘some masters to heal the sick, for they are many’.Footnote 11

According to information from the general register (Tombo Geral) of the Estado da Índia, completed in 1554, and the budgets (Orçamentos) for 1571, 1574 and 1581, 9 of the 14 forts erected in the Estado da Índia had misericórdias – Hormuz, Diu, Daman, Bassein, Cannanore, Chaul, Goa, Cochin and Malacca – seven of which administered their hospitals as service providers paid by the royal exchequer.Footnote 12 The misericórdias in Diu, Mozambique Island and Rios de SenaFootnote 13 preceded the city councils and even performed some of their functions. Contemporary accounts reveal a scene of overall penury in these hospitals, with shortages of everything, especially staff. This was even the case in Mozambique Island, which had the most important hospital for treating the sick on the carreira da Índia (‘India run’).Footnote 14 In fact, surgeons (almost always military surgeons) only began to arrive in Mozambique in the late seventeenth century, with the increasing emphasis on territorialisation policies.Footnote 15

Medical personnel were also scarce in Portugal’s other colonies in Africa. In São Tomé and Príncipe, for example, during the golden age of sugar production (1525–67), there is only a single record of a European surgeon to work in the hospital and perform home visits. That was also the case in Guinea, Cape Verde and São Jorge de Mina, even during the offensives by countries that were trying to break Portugal’s trading monopoly. Episodes like that involving Fernando de Alcalá, an inhabitant of Fogo Island in Cape Verde, were common in these colonies: he qualified as a surgeon on 29 December 1536, and on 3 January, the following year, the chief physician of the kingdom granted him a licence ‘to treat with medicine’. Even though this was a temporary licence restricting him to providing medical care only in the absence of academically trained physicians, it effectively became a full medical licence, as Cape Verde only received its first university graduate doctor in 1618 (and its second in 1643Footnote 16). Fernando de Alcalá had not taken any of the legally prescribed examinations; the Lisbon medical authorities had been satisfied with the information he himself had provided that he had the necessary skills to work as both a surgeon and a physician.

In Angola, medical assistance from the crown only materialised after the appointment of the first governor, Paulo Dias de Novais, in 1575 and the subsequent foundation of the city of São Paulo da Assunção de Luanda. Spurred by the crown’s high expectations in opening up Portugal’s largest colony on the west coast of Africa, a number of surgeons and apothecaries and even some physicians volunteered to serve the country in the fort and garrison.Footnote 17 However, the almost constant state of war, the violence of the deported prisoners sent there (‘the villainous deportees corrupted by so many abominable abuses’), the difficult epidemiological conditions, frequent famines and lack of medicines soon gave Angola a bad reputation and stemmed the flow of health care professionals from Portugal. Before the century had ended, the colony was already reduced to depending on services provided by the odd deported surgeonFootnote 18 or naval surgeons on ships that put in to the port.

On the other side of the Atlantic, the first crown-approved health care practitioners similarly arrived in Brazil to serve the governors and other government and church bodies, as larger swathes of territory were explored and the country was organised administratively in the 1530s and 1540s. But it was only in the early years of the following century, in the context of the Dutch–Portuguese War and military resistance to invasion by the Dutch West India Company, that there was any significant presence of European health care professionals. As previously demonstrated,Footnote 19 the emphasis in Portuguese America was on military surgeons, a separate group in terms of their training (which was severely criticised by the civilian authorities), who formed a parallel system that used the same names – chief physician and chief surgeon – for its top posts. The crown required several municipal councils in Brazil to pay the salaries of the military chief surgeons stationed in the areas under their jurisdiction, on the promise (rarely kept) that they would also attend the civilian population.

The exception in this state of affairs was North Africa, the first arena of Portuguese colonial occupation. Its proximity to Portugal was a decisive factor in the crown’s decision to copy there the health and welfare arrangements that were being put in place in the home country, based on the triad of misericórdias (founded at an early date in Alcácer Ceguer, Arzila, Ceuta, Tangiers, Safi and Azamor), hospitals and health care professionals. As in Portugal, most of these personnel were recruited locally and their skills were validated in Lisbon by the chief physician and chief surgeon of the kingdom. The North African case reveals a certain flexibility in the way royal policy dealt with the different social realities of the empire: while it persecuted and expelled religious minorities in Portugal, it granted a surgeon’s licence to Araby Fayam in TangiersFootnote 20 and a medical licence to Abraão, chief rabbi of the Jews in Safi, who also performed judicial duties in the name of the King of Portugal. Both Araby Fayam and Abraão served their communities through the partido system, in which health professionals were hired and paid by local councils. Medical partidos were also made available in Alcácer Ceguer, Safi, Ceuta, Azamor and Arzila, mostly filled by local residents. There is no evidence that the chief physician or chief surgeon, or even their representatives, ever went to those places to examine candidates or that the candidates had gone to Lisbon to take the examinations, so official oversight was almost certainly limited to the validation of local knowledge and its incorporation into the legal standards prevailing in Portugal. By the 1550s, Portugal had lost most of its possessions in Morocco.Footnote 21

In short, the Portuguese crown appears, overall, to have had no explicit policy in the sixteenth century to endow its colonies with health care professionals from the home country. As would happen in the other European empires, the personnel that did arrive sporadically in the colonies worked almost exclusively in the service of the colonisers. In those early years, only Goa enjoyed some latitude in terms of professionals from Europe,Footnote 22 who worked either in hospitals – the city had four in the first half of the sixteenth century: the Misericórdia Hospital (known as Todos-os-Santos Hospital from the end of the century onwards), Piedade Hospital (run by the senate), the Poor Hospital (Jesuit) with its leprosy ward and the Royal Hospital (administered by the crown, mostly for military patients)Footnote 23 – or in private practice. Many of those in private practice, such as Garcia de Orta, were New Christians who had fled Portugal for fear of the Inquisition. At that time, Goa was Portugal’s major colonial investment, where it reproduced the administrative and religious apparatus of the home country by instituting a viceroyalty and establishing a court of the Inquisition (1560). It was here that measures to regulate health care practice and practitioners were first tried outside Portugal.

Taking regulation to the Estado da Índia and from there to Brazil

The first crown intervention to regulate medical practice in the empire occurred in the Estado da Índia during the reign of King João III (1521–57). We are informed of this indirectly in a letter from King Sebastião (1557–78) to the viceroy dated 27 November 1563 (referring to another of 6 March that year), which transcribes part of a decree (undated) issued by his predecessor ordering that ‘there should be no Brahmins in my lands since they are prejudicial to Christianity and the increase thereof’ and requiring that ‘heathen doctors’ be replaced with Portuguese professionals and Christian converts (‘Christians native to the land’).Footnote 24 While often cited, King Sebastião’s letter has been misinterpreted, not only because the words transcribed are not his but also because he made a very significant change to their content: while King João only excluded farmers from the expulsion order, King Sebastião also ruled it should not apply to ‘doctors, carpenters, blacksmiths, nor apothecaries, nor renters of my rents (…) unless they are prejudicial to Christianity.’ Although the king had consulted the archbishop of Goa as well as the religious orders ‘and some scholars’ before writing the letter, 4 years later, the religious authorities at the first provincial council in Goa (1567) were much more assertive about the use of Hindu healers (‘let no man of faith be treated by an infidel physic’ nor resort to midwives and barbers), but they left open the possibility that that could happen ‘when convenient’, provided it was authorised by the prelate and on condition that they did not teach their trades. In a crescendo of violent language, the third council (1585) made it compulsory for Brahmin doctors to be inspected ‘several times a year’, but it could not go against the royal order that the harm done by Hindu doctors needed to be demonstrated. What is more, the same council recognised that ‘many infidel, especially heathen doctors’ were consulted by the city’s population.Footnote 25

The sanitary and epidemiological conditions in Goa were deteriorating – in addition to endemic diseases like dysentery, typhus and infectious fevers that sprang from stagnant waters, the seamen who disembarked from visiting ships came with scurvy and other diseases. After the siege of 1570/71 and a series of smallpox, malaria and cholera outbreaks, which claimed the lives of many PortugueseFootnote 26 (including two viceroys in 1581 and 1588Footnote 27), the number of people seeking treatment from pandits (Hindu priests with healing knowledge) and vaidyas (practitioners of Ayurveda) surged, as Jan Huygen van Linschoten described in the 1580s,Footnote 28 not least because Portuguese doctors in the colony were becoming scarcer and scarcer. Coimbra was still training very few doctors, and they were almost guaranteed to find jobs in Portugal itself,Footnote 29 apart from which they would have been aware of the difficulties of the sea voyage and the incapacitating or even fatal diseases that struck many of those who left.

Unable to entice doctors to India, as it acknowledged in March 1583,Footnote 30 the crown sought to improve conditions in the ruinous Royal Hospital in 1591 by handing it back to the Society of Jesus (which had previously managed it in 1579–83) and ordering a new hospital to be built in 1593.Footnote 31 In January 1607, however, the crown forbade the physicians and surgeons accompanying the viceroy to work in the Royal Hospital until they had acquired the ‘qualities of the land and the manner of healing there’.Footnote 32 This decision may have been prompted by the senate, as the letter it sent to the king in 1603 would indicate,Footnote 33 but it was probably also due to the influence of the Jesuits, who feared interference from outsideFootnote 34 or were merely convinced that Indian healers were more skilled than Europeans.Footnote 35 The ban was immediately challenged by the physicians and surgeons, but it meant that they were kept away from the hospital and lost the corresponding additional salary, given the limited duration of their commissions to work in Goa. In 1613, when the new hospital that so enchanted Pyrard de Laval was in operation, the king revoked the ban and at the same time appointed the doctor Manuel da Fonseca as chief physician of the Estado da Índia.Footnote 36

Manuel da Fonseca appears to have been the first chief physician to be given legal and regulatory powers for the whole of the Estado da Índia (this position should not be confused with that of the chief physician of GoaFootnote 37), although he was 5 years late in taking up the post.Footnote 38 The fact that the first chief surgeon of the Estado da Índia, Domingos Fernandes Delgado, had been appointed in 1604Footnote 39 is evidence for a new stage in the process of organising the field of health care in the Estado da Índia, which culminated in the Postura dos físicos, cirurgiões, sangradores e boticários (Bye-law of Physicians, Surgeons, Bloodletters and Apothecaries), approved by the municipal senate on 3 November 1618.

While it did not go into functional explanations, the Postura referred back to the ‘chief physician’s statute’, that is, the statute of the chief physician of the Kingdom (1515–21), which, as already mentioned, set out the terms on which he could award licences to empirically trained apothecaries and physicians. Presumably, the same terms would also have applied to the chief surgeon of the kingdom (who only gained a statute in 1631) with regard to surgeons and bloodletters. However, the Postura also demonstrated the supremacy of the powerful Goan senate over health care matters in the Estado da Índia. It basically subordinated the new authorities – the chief physician and chief surgeon – to its own ends. It was their job to examine candidates to test their knowledge, but, as the senate claimed the right to issue licences to practise, it used the doctors in order to legitimise its own power. Moreover, although these licences were issued in the monarch’s name, they were not registered in the royal chancelleries in Lisbon as happened with all the other colonies. In practical terms, that meant that the chief physician and chief surgeon of the Estado da Índia were not hierarchically subordinate to their counterparts in the Kingdom of Portugal (indeed, royal appointments to these positions in the Estado da Índia continued even while the positions in Portugal remained vacant between 1770 and 1782) but answered only to the king and the Goan senate. It is also significant that the Postura legalised the work of heathen physicians (vaidyas and other non-Christians), provided they remained under the wing of the chief physician and chief surgeon. Even though it limited their number to 30,Footnote 40 it removed the authority that the church had given itself in the provincial councils to make ‘infidel doctors’ dependent on the prelates’ goodwill.

In short, the Postura dos físicos, cirurgiões, sangradores e boticários recognised the existence of the two different categories of healers – heathen physicians and physicians according to European canons – and accommodated the local medical culture within the regulatory protocols of the colonisers, while affirming the power of the Portuguese crown and the municipal senate, to which the chief physician and chief surgeon of the Estado da Índia owed their allegiance. Their subordinacy may have made it even more difficult to recruit candidates for both posts; in fact, that of chief physician remained vacant for long periods.Footnote 41 In metropolitan Portugal, members of the Coimbra medical elite held both these positions but not in the Estado da Índia, where they became neither chief physicians – except for some who were trying to flee the authorities (or even prison) or had complicated family situationsFootnote 42 – nor chief surgeons, many of whom were trained on ships and/or in military campaigns (the main exception being the doctor Pereira e Moreira in 1751–54Footnote 43). Our ongoing research shows that while the post of chief surgeon of the Estado da Índia represented the culmination of many surgeons’ careers, that of chief physician served more as a springboard for doctors to achieve higher things, as happened with Simão Roubão da Costa, who became chief physician of the kingdom in 1634 after serving 6 years as chief physician of the Estado da Índia.Footnote 44

An interesting example of somebody who benefited socially and financially from being the chief physician of the Estado da Índia was Francisco Vaz Cabral, who used his experience there to persuade the crown to start organising health care in Portuguese America. Vaz Cabral put himself forward to be both chief physician and chief surgeon of Brazil at the same time, in addition to holding a partido as a municipal doctor.Footnote 45 In the middle of the Dutch–Portuguese War, when there were increasing numbers of military surgeons in Brazil, the crown accepted Vaz Cabral’s petition and, in an order of 28 March 1634, appointed him to all the positions he had requested, with ‘the consent of the chief physician and the chief surgeon of this Kingdom’. In 1639, Vaz Cabral also managed to be made ‘chief physician of the army that is going to Pernambuco’, thus combining the military and civilian spheres, something that never happened in Portugal itself.Footnote 46

In this way, health care regulation started in Brazil through private initiative, although central government benefited by receiving the fees for issuing licences to practise and opening apothecaries’ shops. With the increasing exploitation of the colony based on sugar production and the slave trade and the growing population dependent on the crown, the posts of chief physician and chief surgeon became more attractive – and more disputed.Footnote 47 In Lisbon, tensions were growing between the chief physician and chief surgeon of the kingdom,Footnote 48 which resulted in both of them being replaced in the space of 2 days (23 and 25 June 1699Footnote 49). With the new incumbents, the duplication of these positions in Brazil came to an end. Brazilian health care was from then onwards to be administered by the chief physician and chief surgeon of the kingdom through their commissioners, who at a local level would run examinations, oversee health care professionals and inspect apothecaries’ shops, as was the case in Portugal. The licences these commissioners issued would remain provisional until they were registered in the Royal Chancellery in Lisbon, again as happened in Portugal.

Brazil’s incorporation into the regulatory system of the home country lasted until 1808, when the crown abolished the Protomedicato, the institution that had replaced the chief physician and chief surgeon of the kingdom in 1782. (Brazil was the only overseas territory in which the Protomedicato had a branch office.Footnote 50) Prior to this integration, the bishop and the governor of Cape Verde had also applied to reproduce Vaz Cabral’s model – investing a single person with the titles and duties of both chief physician and chief surgeon – ‘in the islands and district of Guinea’, but in 1676, the crown rejected their suggestion, perhaps because it would have created new financial burdens in a region with relatively few colonists. No specific mechanism to regulate the field of medicine was ever developed in Portuguese Africa throughout the early modern period; there was only a scattering of intermittent control measures carried out by the chief physicians of the colonial capitals, when Lisbon managed to find anybody to appoint to those positions.Footnote 51

Medical training in the Estado da Índia

Following the Postura of 1618, the chief physicians of the Estado da Índia may have issued a hundred licences to practise medicine.Footnote 52 Among the new licensees were some of the 80 or so ‘masters or pandits’ who were living in Goa at the end of the century, if we are to believe João dos Reis, the author of Caderno de Várias Receitas Medicinais Orientais. Footnote 53 All of them were ‘lacking in science and treat only with the little experience that they have,’Footnote 54 according to crown officials serving in Goa in 1691, who continued to call for physicians trained in Coimbra. The only European doctor in the Royal Hospital at that time was the chief physician.

The letters that the viceroys and governors wrote to the crown pleading for doctors to be sent out were very dramatic, especially when death visited their peers, as happened in the space of a few months in 1690–1, when two governors (D. Rodrigo da Costa and D. Miguel de Almeida), two judges and the chief physician himself, Simão de Azevedo, all died (followed by the inquisitor the following year). Almeida, who succumbed before he had been in Goa for a year, even wrote in a letter to the king on 2 November 1690 that he considered it a ‘kind of cruelty to send a thousand Portuguese to this State, and it being their principal intent to arrive and live here for many years, not to send doctors to treat them both on the journey and here’.Footnote 55

In Spanish America, the Habsburg monarchs had tried to solve the problem of the lack of doctors by endowing the universities, which had begun to appear in the 1550s, with medical courses (in addition to Protomedicatos in Mexico, Lima, Guatemala and Bogotá, where would-be physicians and surgeons could present themselves for examinationFootnote 56). This, however, was not the option taken by Portugal (it neither founded universities nor introduced medical courses) – not even during the Iberian Union (1580–1640). In fact, while Filipe II of Portugal (Felipe III of Spain) was putting his seal to the Goan Postura of 1618, which allowed medical credentials to be given to people with no academic training, in the Spanish American colonies, the reform of medical courses was already under way, making them identical in form to courses in Spain.Footnote 57

The first attempts to teach medical knowledge and train teachers of medicine in a Portuguese colony apparently date back to March 1681. It was not a case of training in a university context, however, but a contract with the chief physician of the Estado da Índia, Inácio Mendes de Oliveira, to teach the Prime and Vespers (two of the four main courses that made up the medical curriculum in force at the University of Coimbra) at the Royal Hospital in Goa for 12 years; he would thus teach four courses of study each lasting 3 years. The contract would be renewable for 3 years, according to the royal decision, depending on the quality of the service rendered by the chief physician. After graduating, the new doctors would become teachers in their own right and thus continue the medical teaching programme.Footnote 58 However, for some unknown reason, Inácio Mendes de Oliveira appears to have returned to Portugal much earlier than expected without having done any teaching at all.

It would be more than a decade before the crown returned to the idea of medical teaching in Goa. On 23 March 1691,Footnote 59 the task was entrusted to the new chief physician and chief surgeon, Manuel Roiz de Sousa and Feliciano Gonçalves, respectively. Once again, however, the plans came to nothing: Gonçalves changed his mind about going to India, whereas Roiz de Sousa fell ill on the voyage and remained ill throughout his time in Goa, where he did little work as a doctor and none at all as a teacher. There would be a further attempt before the end of the century, but the physician who had volunteered to sail to Goa fled from the docks in Lisbon as he was about to embark, making it impossible for anyone else to take his place. The university rector, who shortly before had been boasting about his powers of persuasion over the putative traveller, considered his disappearance to be a bad omen and predicted that ‘with this example there would not be anybody who wanted to go’.Footnote 60 Medical studies at the Royal Hospital in Goa eventually began only in 1703,Footnote 61 with the chief physician, Cipriano Valadares, teaching the Vespers course in medicine until 1713. They continued for a few more years under his successor, Manuel da Rosa Pinto (who only taught the Prime courseFootnote 62).

The crown more than once urged the governors-general to found ‘Schools of Medicine and Surgery with hospital practice’ (for which ‘the natives of India are in fact well suited’Footnote 63) but to no avail. The reason for that may have been the tempestuous relations between the chief physicians and the hospital administrators (the Jesuits), not to mention the war that ensued after the Maratha invasion, which led to territorial losses in the Northern Province and the occupation of part of Goan territory.Footnote 64 Medical teaching only resumed in 1801 during the commercial recovery of the Estado da Índia and then only for a dozen years in the hands of the chief physician, António José de Miranda e Almeida. Although information on the process is lacking, the possible influence of Britain, which controlled Goa at the time,Footnote 65 should not be ruled out, given the development of medicine in its hospitals, which had been run by the army from the General Hospital in Madras since 1790.Footnote 66

Even less well documented is surgical training in the Estado da Índia, which, as was the case for most surgeons at the time, consisted of practical apprenticeship – learning on the job – in hospitals or private practice, on sea voyages and/or in theatres of war. That was the kind of training received by Manuel Vaz Fagundes, the chief surgeon of the Estado da Índia between 1716 and 1725. Correia credits Fagundes – who had learnt surgery in the trenches – with training ‘several generations of surgeons’ at the Royal Hospital in Goa for the fleet and army. No documentary evidence has been found to confirm this claim; on the contrary, there are numerous complaints about the scarcity of surgeons at the hospital,Footnote 67 a shortage that is indirectly corroborated by the mention of individuals with ‘half surgery’ licences well into the eighteenth century (such licences were usually issued to bloodletters, who had disappeared in Portugal in the early seventeenth centuryFootnote 68) and the presence of ‘surgeon-assistants’ (cirurgiões-ajudantes), who were almost always underlings with no health care knowledge. Some surgery may also have been performed illegally, even in the hospital; trainees who knew enough to pass the examination might choose not to be examined because of the associated cost and inconvenience. In fact, that may also have happened during the only period when surgery was taught more systematically at the Royal Hospital in Goa (1789–1823), according to the model used at the São José Hospital School of Surgery in Lisbon.Footnote 69 The training was given by Francisco Manuel Barroso da Silva, who was appointed chief surgeon of the Estado da Índia in 1785 after the post had been held by Goans for 20 years.Footnote 70

The situation in Brazil was different precisely because licences were issued through central government agencies in Lisbon and were subject to tighter control (initially by the chief physician’s and chief surgeon’s commissioners and later by the Protomedicato and its agents). Besides, surgeons in Brazil appear to have enjoyed higher status than anywhere else in the empire. To a great extent, this was due to the military chief surgeons, who were responsible for offering a special kind of training organised with the medical authorities,Footnote 71 which from the mid-eighteenth century onwards led to the replacement of immigrant surgeons from Portugal with individuals born in Brazil. Under the Protomedicato and with supervision from the governors and captain general of the captaincies, this experiment was carried over to the military hospitals in São Paulo,Footnote 72 Rio Grande de São Pedro,Footnote 73 Mato GrossoFootnote 74 and Vila Rica. By 1604 in Vila Rica, to teach surgery (‘operating medicine’) was one of the duties of the chief surgeon of the Minas Gerais Cavalry Regiment.Footnote 75

The information that several of those surgeon-teachers also taught the ‘obstetric art’Footnote 76 suggests that a more extensive surgical training programme was being developed along traditional lines.Footnote 77 Similarly, on 11 September 1791, a ‘class in practical medicine, with anatomical instructions’ was started in Luanda Hospital in Angola, organised by the chief physician José Pinto de Azeredo. Although it was called ‘School of Medicine’, it merely provided trainee surgeons with a little medical knowledge.Footnote 78 It was a complete failure, as Pinto de Azeredo admitted, adding that he considered ‘the sons of the land quite able’ but lazy, with no interest at all in what was taught.Footnote 79 It should be noted that it was only after the Portuguese crown had managed to reduce the power and autonomy of the Macau Senate in the mid-eighteenth century that Lisbon began to send out a trickle of health care professionals to that part of the Empire. According to the central archives, only fourteen appointments were made in the period 1750–1831, most of them surgeons.

Turning a medical problem into a political one

Despite all the vicissitudes that the teaching of medicine in Goa endured, Correia mentions that almost 190 physicians must have graduated there during the eighteenth century (Figure 2) and 86 of them after 1752.Footnote 80 Mapping the available documentation shows that although Goa continued to dominate as the place where most physicians lived and worked, less coastal sites such as Carmona, Navelim, St Paul and Chorão Island began to appear up to 1750; Daman and Diu in the following two decades; and Cabo da Rama, Chorão, Loutolim, Aldona, Chinchinim and Serula in the 1790s (Figure 3).Footnote 81 A few licences to practise were issued to pandits in the 1720s and 1730s,Footnote 82 but the vast majority of the new doctors (and all of those who graduated after 1752) were Portuguese born in India. How can these numbers be reconciled with the fact that only one (and rarely two) medical disciplines were taught in the Goa hospital in the early part of the eighteenth century, since the chief physicians had to combine this work with treating hundreds of patients every year?

Figure 2 (Colour online) Licensed physicians and surgeons in Mozambique and Portuguese India (1500–1752). Data from the Medical Professions Database, 1430–1826.

Figure 3 (Colour online) Physicians and surgeons licensed to practise by the chief physician and chief surgeon of the Estado da Índia (1753–1821). Data from the Medical Professions Database, 1430–1826.

The answer is that the crown turned a medical problem into one of governance. In other words, it appears to have acknowledged the difficulty in transposing to India the academically based form of training inspired by the University of Coimbra course in medicine and therefore made the decision – most likely at the Goan senate’s urging – to encourage application of the clauses in the 1618 Postura that allowed doctors to be ‘manufactured’ (in the university’s terminology) in line with European medical standards based on recognition of their empirical knowledge.Footnote 83 This was not unlike the situation in Portugal (under the chief physician’s statute of 1515–21, as mentioned above), but there were features specific to the Estado da Índia. First, there was a tendency not to differentiate degrees of candidates’ knowledge: most licences to practise were issued for life, with no restrictions on the kinds of medical procedures permitted,Footnote 84 even where the holders were not found to have any particular aptitudes other than ‘manifest healing qualities’.Footnote 85 To give an idea of the difference, of the 883 licences issued by the chief physician of the kingdom and by the Protomedicato for Portugal and the empire (excluding the Estado da Índia) between 1701 and 1801, only 154 were full ‘medical licences’; all the rest only gave temporary permission to perform certain medical procedures.Footnote 86 The second specific feature was that these doctors were allowed to combine the posts of physician and apothecary, which was against the law in Portugal and also blurred the line separating the civilian and military spheres, thus creating a unique category of practitioner. Lastly, given the scarcity of European physicians in the Estado da Índia and the almost complete lack of any medical teaching, the chief physicians must have validated far more Indian medical knowledge than European. That appears to have been the case even when the impact surgeons may have had in spreading knowledge is taken into account; the training received by surgeons working in Portugal was universally considered deficient – some were even illiterate. There are no objective reasons to think that only the most knowledgeable surgeons would have emigrated.

In practical terms, the medical authorities legitimised what historiography today terms cultural hybridity.Footnote 87 This was not the conclusion drawn in the early twentieth century by the doctor Alberto Correia, whose reading of the reports drawn up in 1802 by the chief physician of the Estado da Índia, Miranda e Almeida, was that since the 1770s Goa had been experiencing a ‘forced, disoriented westernisation’, which had produced health care professionals who were neither doctors nor pandits.Footnote 88 It is difficult to see where this overriding influence of western medicine would have come from, given that there were hardly any European practitioners, at least in state institutions. Instead, I propose that when the crown decided to affix the royal seal to certify the medical knowledge of a group of locally born practitioners of Portuguese descent, it was not only trying to placate the fears of those who kept on demanding doctors trained in Portugal, but it was also attempting to establish social hierarchies by setting doctors apart from other professionals and, in the process, making its own presence felt more strongly in the colony.

This policy required obedient chief physicians who would merely carry out orders without questioning them.Footnote 89 Any chief physician who did not do so on grounds of the ‘superiority’ of his Coimbra degree was severely punished. Such was the fate of Bernardo de Almeida Torres, who was appointed chief physician of the Estado da Índia on 28 March 1748 and sent back to Portugal by the viceroy on 14 October 1750Footnote 90 after he had decided to examine all doctors who had been awarded licences without attending the medical classes. Another example was Luís da Costa Portugal, who disembarked as chief physician in Goa on 1 October 1774 and held the post until 1782. He not only demanded that candidates for the course of study in medicine, which he was required to found, should first have passed examinations in Rhetoric and Philosophy, which in practice meant that they would have no medical training during his contract (as indeed happened), but he also presented himself as the ‘only minister of health in these States of India’.Footnote 91 He also refused to treat locally trained doctors as his peers, even those he licensed. In the end, he was arrested and imprisoned on the governor’s orders.

These trends in the field of health care cannot, however, be taken in isolation. What was at stake was the crown’s policy of elevating the Estado da Índia, which included giving people born there the ‘same honours, prerogatives and privileges as those born in the kingdom, those native to the land to be given preference in access to jobs’,Footnote 92 as stated in the royal decree of 2 April 1761. Despite resistance from the Portuguese who were serving the crown in India, the decree was eventually implemented in all areas of government, especially after the ‘affirmation of the Goan elite’ in 1792 and the ‘naturalisation’ of posts and duties.

In this context, more medical licences were awarded and physicians serving in the army – in the Ponda and Bardez Regiments, among others – were promoted to the rank of lieutenant.Footnote 93 A similar philosophy led to the appointment, albeit provisional, of the first Goan chief surgeon and chief physician – António Xavier de Noronha (1766)Footnote 94 and António dos Remédios (1770),Footnote 95 respectively. Remédios had been trained in the Royal Hospital, where he had worked for 39 years; for the last 15 years, he had replaced the chief physicians during their repeated absences. When asked to stay in the hospital after the chief physician and chief surgeon had returned to Portugal, Remédios demanded to be appointed to the post (1770–74). In 1782, another Goan, the Brahmin Inácio Caetano Afonso, who had recently been licensed by the chief physician Luís Portugal (who had succeeded Remédios and had never taught medicine, as previously mentioned), took over the post of chief physician and held it until his death in 1798.Footnote 96 The Estado da Índia would only have a Coimbra-trained chief physician again in 1801 and even then just for little more than a decade.Footnote 97

As in other fields, these health care appointments were not to the liking of the governors general, who always emphasised their temporary nature and insisted on referring to locally trained doctors as ‘amateurs of medicine pretending to be professional doctors’, blaming them for the ‘great mortality’ recorded in the Royal Hospital in Goa.Footnote 98 Chief physician Miranda e Almeida, a Coimbra graduate, held similar opinions, but not even the 59 doctors he trained (in 3-year courses of study, including theoretical and practical teaching) were spared the criticism of the governors general, who continued to claim that Goan doctors lacked ‘absolutely all the prior knowledge that opens doors and leads students into this science and, one may even say, without books and knowledge of the discoveries in this science that every day are being made so advantageously to humanity.’Footnote 99

Doubts about the quality of the medical training given in Goa were also entertained by the governing authorities in Mozambique, a colony that separated from the Estado da Índia in 1752. Of all the larger areas governed by Portugal, Mozambique, together with Angola, had the greatest difficulty in getting health care professionals from Portugal. Low-status Indian healers had worked in Mozambique since the early days, hoping to gain social capitalFootnote 100 that they would use to improve their position in society on their return home. The distaste that governors and military commanders felt for them was equally long-standing, as they preferred exiled surgeons from metropolitan PortugalFootnote 101 (as were found in Tete, Cabo Delgado, Quelimane and Inhambane in the 1750sFootnote 102) to doctors licensed by the Goan senate.Footnote 103 When, in 1815, the crown offered a Goa-trained doctor to the governor general of Mozambique captaincy to serve as chief physician, the governor refused and the position was filled in 1816 by a doctor who had trained abroad: António José de Lima Leitão, a Paris graduate, who had been surgeon-assistant to General Junot during the French invasion of Portugal. His appointment as chief physician of MozambiqueFootnote 104 enabled him to erase the stigma associated with his past as a foreign-trained military surgeon and physician and marked the beginning of his professional and social ascent, which he had been denied in 1814 when he returned to Lisbon.Footnote 105 In 1819, he was appointed acting chief physician and intendant general of agriculture of India, and in 1822, he became a deputy in the General and Extraordinary Cortes [Assembly] of the Portuguese Nation, after founding a new course of study in medicine and surgery in Goa.

Conclusion

The essentially administrative and standardised nature of the information contained in the main documentary resource used for this research (a database of physicians, surgeons and apothecaries) is not particularly fruitful for the study of knowledge production and dissemination or even the role of health care professionals as go-betweens (to cite Kapil Raj’s important workFootnote 106) brokering contact between the European and African, South American or Asian medical cultures.

What the documents do tell us with some certainty is that, in contrast to metropolitan Portugal, the empire was not a priority for the Portuguese crown in terms of medical care and welfare and that these policy areas were not used as political or legal tools of government in the colonies in the early modern period. Overall, without ignoring contingent and localised policies especially in wartime, central government measures were limited in extent and were adopted case by case in response to pressures reaching the kingdom – from local populations through their municipal councils, in the case of Brazil; from military commanders in Africa; or from the authorities that represented the crown or the church in the Estado da Índia. The circumstances in other European empires were probably not very different, but the Portuguese crown seems to have faced greater challenges, partly for demographic and economic reasons but also because of doctors’ reluctance to leave Portugal, especially when the employer was the government.

Even so, the crown did take notice of the specific conditions in each of the occupied places and dealt with them as best served its own interests and those of the local elites. In this regard, the field of medicine was organised in two different ways in the empire. In Africa and Brazil, it ended up subordinate to the authorities in Lisbon (the chief physician and chief surgeon of the kingdom), who controlled it in the same fashion as they did in metropolitan Portugal. In the Estado da Índia, on the other hand, the field had its own dynamics, and four sequential phases of administration can be identified. At first, under King João III, Portugal took an authoritarian approach with a view to restricting the field to Portuguese health care practitioners or local Christian converts. This was followed by a period of coexistence between European and Indian medicine, under the royal decree of November 1563 and the Goan senate’s bye-law of 1618, the Postura dos físicos, cirurgiões, sangradores e boticários, when the posts of chief physician and chief surgeon of the Estado da Índia were created. In the third phase, after 1681, there was an attempt to implement European medical training. Finally, this gave way in the eighteenth century to administrative licensing; although sanctioned by Portuguese law (the chief physician’s statute of 1515), this practice legitimised the blending of local and European medical knowledge, in which the local apparently dominated. The new policy must have been welcomed (and possibly even suggested?) by the Goan senate, which would no longer tolerate arrogant chief physicians who questioned the scientific credibility of doctors licensed in this way. The relatively marginal role played by the medical authorities in the Estado da Índia (despite their independence from their counterparts in Portugal), together with the lack of a physical administrative structure in Goa with permanent posts and an established hierarchy (as there was in many other central government agencies), helps to account for the numerous difficulties the crown had to face in managing the medical field in Portuguese India.

The question arises here of whether health care practices brought from Portugal had a disruptive effect on local practices in its colonies in the early modern period, as France and England sought to achieve in theirs. There is no real evidence for this. Even if there were no other arguments, the numbers – or, rather, the lack of them – speak for themselves: the University of Coimbra turned out few graduates and the doctors it did train had priority access to central and local government posts, while doctors trained abroad were readily absorbed by the growing social demand for health care. In objective terms, the difficulties of the voyage, the risks to life, the poor salaries and the limited career prospects did not justify leaving Portugal, unless there were other, weightier reasons for doing so – such as getting out of prison, escaping from marital problems or hoping to acquire some social capital, as was the case for professionals from the lower echelons of the population, such as doctors who had depended on scholarships to study at the university. Of course, there were also surgeons with their practical knowledge, but it should not be forgotten that many of them were trained on the battlefield or on sea voyages, especially on the route to India.

Without wishing to endorse Donald F. Lach’s unidirectional explanation of the importance of Asian culture in European culture,Footnote 107 I believe the influence of the colonies on the health care practices of the Portuguese may have been much greater than the influence Portugal exerted there until the beginning of the nineteenth century. It is, nonetheless, a difficult matter to assess. The works of some of the doctors and surgeons who were stationed in the empire are relatively well known but, unlike the situation in Britain, for example, there has been no systematic survey of the medical literature produced in this context or, more particularly, of its impact on everyday medical practice. Even so, it is noteworthy that the knowledge acquired in the empire did not make its way into the teaching curriculum at Coimbra University’s Faculty of Medicine – at least, not by the beginning of the nineteenth century. Even the new official pharmacopoeia (the Farmacopeia Geral para o Reino e Domínios de Portugal), compiled by one of its professors, Francisco Tavares, and published in 1794, not only was produced without the university’s knowledge but did not include many of the drugs from the empire, even though the trade in these drugs had burgeoned during colonial exploration. Besides, the fact that the university seems to have played virtually no part in the affairs discussed here should itself be a subject for research.

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to Margarida Sobral Neto for her critical reading of the manuscript and her suggestions for improvements, and to the reviewers for their invaluable comments. I must also thank Luís Gonçalves for preparing the maps and Christopher J. Tribe for translating the original Portuguese version into English. This work is funded by national funds through the Foundation for Science and Technology, under the project UIDB/00057/2020