1 Introduction

‘Be there for your friends, don’t let irrational fear take the upper hand and don’t let anyone walk all over you because of AIDS!! Together we can break the steep increase!’Footnote 1 This was the encouraging message in 1985 from a gay man, nurse and AIDS activist, directed at men who had sex with men to abstain from donating blood. The first cases of AIDS in Norway were reported in the early months of 1983, and the news was widely communicated in the press, in the national medical journal and in the weekly reports of infectious diseases by the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.Footnote 2 From the mid-1970s, activists and health professionals in the gay and lesbian communities had started to address the unmet health needs in their communities. When AIDS arrived, activists mobilised formal and informal networks between the gay and lesbian communities, activist organisations and authorities to hammer out a Norwegian AIDS policy. This article is the first to tell the story of early AIDS activism in Norway.

Historians have argued that scholarship on HIV/AIDS policy has tended to follow two strands of argument.Footnote 3 One strand has analysed policy as part of conservative, liberalist agendas spurred by mass media hysteria and ‘new moralism’ (Thatcher, Reagan).Footnote 4 The other strand argued that populist backlash had little effect on actual policy-making, which ended up being more shaped by medical ‘professionalism’ and activists.Footnote 5 This strand included an attendance to the ‘pre-history’ of AIDS, contextualising AIDS responses in postwar policy debates and tensions.Footnote 6 This article follows the latter approach along two lines.

First, it asks how AIDS unfolded in the changing Norwegian public healthcare system of the 1970s and 1980s. The creation of the welfare state and a public healthcare system in the second half of the twentieth century was a political project with wide support across party lines. This included the creation of a centralised health bureaucracy where political and medical professional power became consolidated in the health director, who gained a unique position, directly under the minister, providing the director with broad authority to carve out public health policy and put it into action. Central to this project was a comprehensive concept of health and social medicine as a tool to enforce the welfarist programme – the dominant ‘thought style’ in the postwar health bureaucracy.Footnote 7 In the 1970s and 1980s, the centralised structure had started to fall apart as the counties got increased control over public health policy, and in 1983, the directorate became a strictly professionalised administrative and advisory body. Hence, as the first cases of AIDS were reported in Norway, the health director, who had been the principal advocate for and implementer of public health policy rooted in social medicine, was dethroned from the powerful medico-political position and deprived of political power. How did AIDS play out in this new political landscape? In what ways did AIDS revive, mobilise, challenge and reshape the thought style of social medicine?

Second, the article seeks to position Norwegian AIDS activism within the gay and lesbian health activism preceding AIDS. Even though Norway was an egalitarian country, with strong popular support for the welfare state project, the ‘Social Democratic Order’Footnote 8 was nevertheless a paternalistic, heteronormative and fairly conformist state. The widespread stigmatisation and discrimination of queer people, especially in the healthcare system, led gay and lesbian healthcare workers and activists to establish health services for queer people in the 1970s.Footnote 9 These services and activists would play an important role in confronting AIDS when it arrived some years later, and they played a crucial role in hammering out the Norwegian AIDS policy. By having one foot in the medico-political world and one in the queer communities, they were able to mediate and translate different kinds of expertise and knowledge to the authorities, the public and the affected communities. Gay and lesbian health professionals’ ‘membership’ in the communities gave them credibility when addressing public health issues and preventive work. This unique position enabled them to create preventive health campaigns without being discredited as homophobic representatives of the official policy.

This article argues that it was exactly the ‘amphibious nature’ of their roles that would prove so crucial in the preventive work to come, as gay and lesbian healthcare professionals could freely ‘move’ between the different worlds – the medical, the governmental and that of the communities.Footnote 10 This amphibious role gave them integrity and competence and enabled them to occupy a liminal space, characterised by what anthropologist Victor Turner in another context has defined as ‘that which is neither this nor that, and yet is both’.Footnote 11 Nevertheless, juggling different roles sometimes posed difficult dilemmas: to negotiate insecurities when little was known about disease mechanisms; to seek cooperation with the state without being accused of co-optation, medicalisation and ‘dilution of gayness’; and to avoid AIDS activism overshadowing gay and lesbian liberation work. Moreover, gay AIDS activists were not immune to the reproduction of exclusionary or hierarchical mechanisms within queer communities, and the perspectives of lesbian, bisexual and transgender people were often neglected. These dilemmas were not unique to Norwegian AIDS activists, as, for instance, scholarship on UK AIDS and drug activism has demonstrated.Footnote 12 This article, however, seeks to analyse what was particular about the Norwegian example, how the amphibiousness and ambiguities were played out in a context of a fairly paternalistic welfare state and the landscape of a changing health bureaucracy imbued by the thought style of social medicine.

In her compelling study of venereal disease legislation in the three Scandinavian countries through the twentieth century, Ida Blom argued that the official Norwegian approach to the AIDS epidemic in many ways resembled Sweden’s ‘control-and-contain strategy’.Footnote 13 In 1994, Norway removed its old law on venereal diseases, implementing a new one on contagious diseases, including HIV/AIDS, which included an option to use coercive measures in extreme and rare cases. Denmark, on the other hand, discarded its legislation on venereal diseases in 1988 and followed a ‘cooperation-and-inclusion strategy’.Footnote 14 In this article, based on archival material and a range of oral history interviews with activists, medical professionals and civil servants, I seek to complicate this view by, on the one hand, unpacking how the Norwegian AIDS policy unfolded against the public health thinking of social medicine and, on the other hand, how gay and lesbian activists challenged hegemonic policy, gained political power and mediated between communities and authorities.

In the vast AIDS historiography,Footnote 15 the Norwegian situation has not received much, if any, attention from historians of medicine.Footnote 16 This article seeks to contribute to a growing body of scholarship tracing the genealogy of AIDS activism in gay and lesbian health activism in the pre-AIDS era in various contexts around the world. Certainly, US AIDS activism was largely spurred by conservative politics and political ignorance,Footnote 17 nonetheless, this prism has obscured a more nuanced picture of interactions between health professionals and gay and lesbian communities. In the 1970s, community-based health services were created in US cities that were not merely directed at venereal diseases but which contributed to the formation of a broad concept of gay and lesbian health, including the negative health effects of stigmatisation, racism, homophobia and discrimination.Footnote 18 Moreover, the concept of ‘safer sex’ originates from the pre-AIDS age in the late 1970s San Francisco, where a group of gay-friendly and sex-positive physicians started to address the increased problem of sexually transmitted infections and hepatitis B among gay men.Footnote 19 From early in the US epidemic, activists and medical professionals, including mental health professionals, co-operated in unique ways to prevent, counsel and educate communities.Footnote 20 In European countries, too, the queer communities played an early, fundamental role in the AIDS epidemic. In the UK, activist organisations like the Gay Medical Association and the Terrence Higgins Trust mobilised to provide health education, self-help and buddying services from the early 1980s.Footnote 21 In West Berlin in 1983, a group of gay men and nurse Sabine Lange founded Deutsche AIDS-Hilfe, the national Germany AIDS organisation, by mobilising already existing networks in the gay communities.Footnote 22 In the Netherlands, the fact that gay men were included in preventive work from the beginning ensured that their voices were heard and laid the groundwork for rapid responses to changes in the communities and subcultures.Footnote 23

This article starts by mapping out the development of Norway’s welfare system from the postwar era. In the rest of the article, I unpack Norwegian gay and lesbian health activism by first analysing the pre-AIDS era with the creation of the first public counselling service for homosexual men and women in Norway in second half of the 1970s. This would provide the groundwork for later AIDS activism.Footnote 24 Then, I demonstrate how official Norwegian AIDS policy built on gay and lesbian health activism and, in particular, on the important role played by gay and lesbian healthcare workers. This history is exemplified by thorny topics that dominated the political and public discourse: blood donations among gay men; prevention strategies and information work; and mass testing for antibodies.

2 The Welfare State, Social Medicine and the Directorate of Health

The welfare state that grew out of the postwar era was a cross-party project.Footnote 25 In accordance with the Nordic welfare model, Norway sought to regulate capitalism with strong governmental control.Footnote 26 The welfare state was made possible by the mobilisation of science including social sciences; the Nordic model was a positivist knowledge regime where empiricism, rationalism and quantification were transformed into and supported social-democratic policy.Footnote 27 Medicine was a central tool in this process. National healthcare was a fundamental pillar of the expanding welfare state, supported by physicians in leadership positions who advocated the medico-political project of social medicine. The notion that the political system and societal structures were important to individual health and well-being came from early social-democratic medico-political thinking.Footnote 28 The political became private and the private became political; the societal and individual body were inseparable – leitmotifs in the public health system created before and after the Second World War. But even if the Labour Party played a crucial role, the welfare state project enjoyed broad political support. The centre-right parties played a crucial role in securing a public healthcare system for everybody and broad social security rights for the population. For instance, in the six-year period from 1965 to 1971, when the country was governed by a centre-right coalition, a range of progressive reforms were implemented. Among these were the national public pension system (1966) and the Hospital Act (1969), which created a unified hospital system and made the counties responsible for building and managing the country’s hospitals.

Following the end of the war, the Medical Directorate [Medisinaldirektoratet] and the Medical Department [Medisinalavdelingen] in the Ministry of Social Affairs were merged into one, the Directorate of Health. This gave the director direct access to the minister and turned the directorate into a unique political-professional creature in the Norwegian political system. Through preventive and curative healthcare, the state gradually took responsibility for more and more of peoples’ lives in a system that strongly favoured certain trusted physicians’ knowledge and competence.Footnote 29 Karl Evang, the health director from 1938 to 1972, who had a degree in public health from Johns Hopkins University, arranged for the physicians he appointed to the directorate and for district medical officers [distriktslege] in the health councils across the country to have access to similar courses at the American university. With a strong central health administration dominated by physicians handpicked by Evang, district medical officers were given fairly free rein to use their medical knowledge and authority to pursue the goals of the welfare state by the means of social medicine.Footnote 30 When Fredrik Mellbye became chief medical officer [stadsfysikus] of Oslo Health Council in 1972, he brought with him experience from the Directorate of Health, where he had been the head of the Office of Hygiene. There, he had been convinced of the importance of medicine for society and that modern social medicine with roots in public hygiene was an integral part of a welfare state. Prevention was central to these ambitions, and during the 1970s and 1980s the Council significantly expanded its reach by opening new public health departments, including, most importantly for this article, in 1985, a department for measures against AIDS, as well as a department for primary healthcare and a department providing relief measures to parents with children with disabilities.Footnote 31

Because the public healthcare system was underpinned by the belief that problems and diseases should be addressed and solved by the means of societal solutions, sexual health, or sexology, was integrated into a broad definition of and approach to public health. In the article ‘Sexual hygiene in bourgeois and socialist illumination’, the young Evang, at that time a member of the communist organisation Mot Dag, attacked what he saw as a hypocritical bourgeois sexual morality rooted in Christian ethics full of denial and repressed needs, and argued that capitalism led to ‘over-eroticisation’ and the exploitation of peoples’ desires, and that it prevented the healthy development of sexuality. Socialism, with work–life balance and gender equality, were seen as an antidote to this development. A reorganisation of society, he argued, would do away with patriarchal ethics and capitalism’s exploitation of people’s sexuality, and would lead the population to live emancipated, happy and uninhibited lives.Footnote 32 Throughout his years as health director, Evang personally responded to hundreds, if not thousands, of letters from individuals who wrote about their sexual problems, including sexual guilt, erection failure and pain during intercourse.Footnote 33 In a book about sexuality for lay people, in 1951, he wrote that a change was needed in ‘the current moral views and in society’s attitude’ towards homosexuals to enable ‘happy and worthy lives’.Footnote 34

At Oslo Health Council in the late 1970s, social medicine and sexology were unified in new ways. Here, the country’s first medical position in sexology was established at Norway’s first department of medical sexology.Footnote 35 The department was an instrument for, on the one hand, incorporating the supervision of other health professionals into clinical work and, on the other, merging preventive and advisory work with public awareness work. Here, as we will see, an advisory service for gays and lesbians was established, and an expert group for people who wanted gender-affirming therapy was formalised. The department played an important role in raising public awareness and fostering sexual education in schools, and emphasised family planning, contraception and abortion services for young people. In Our Sexual Life, a book for lay people, Berthold Grünfeld, the department’s first director, wrote that ‘[i]n our society, young people will usually find little or no help in this development of their sexual lives’.Footnote 36 There was an inherent dilemma in modern capitalist societies: on the one hand, premarital sex was sanctioned, on the other, he argued, society, and especially the press, encouraged people to have sex and stimulated sexuality. Grünfeld thought this quandary called for nuanced and scientifically based medical public information. Medical technology and scientific progress were mobilised for the liberation of the population’s sexuality: ‘Increased openness, the access to factual information and not the least, modern and highly efficient prevention have helped eliminate much anxiety, insecurity, fear and uncertainty regarding one’s sexuality.’Footnote 37

However, when Torbjørn Mork – like his predecessor, a physician – became the new health director in 1972, the strongly governmentalised, partly centralised system had started to fall apart.Footnote 38 The Directorate of Health lost much of its power in 1983 as parties on both sides of the political spectrum had become increasing worried about its unique independent and powerful position. The year after, a new healthcare act terminated the role of the government-appointed district medical officer, and by the end of the 1980s the health councils had been dissolved. The tradition of government-employed district medical officers leading the health councils had roots dating back to the mid-nineteenth century. The councils and their medical officers had been a backbone of the public healthcare system and were crucial cogs in the wheel of social medicine.Footnote 39 The reasons for this shift were manifold, but the official justification was democratisation and decentralisation. The protest movements of the late 1960s and 70s challenged a patriarchal, physician-dominated healthcare system, and a number of professionals and politicians wanted a seat at the table.Footnote 40 Even if the administrative and professional axis joining district medical officers, county medical officers and the health director was disrupted, the new municipal medical officers [kommunelege] were still under municipal control. The result was not less but more public control of the health sector albeit on a decentralised level.Footnote 41

Virginia Berridge has argued that UK AIDS policy should be seen in light of the changed landscape of public health in the postwar period, which, with the help of epidemiology, had ‘redefined itself round a focus on the individual rather than the collective or the environmental basis of ill health’.Footnote 42 In the UK, public health thinking witnessed a ‘decline’ in the 1970s and 1980s with the reorganisation of the National Health Service and the termination of the public health role of medical officer of health.Footnote 43 It is tempting to draw parallels to Norway, yet it would be misleading to characterise the structural changes taking place in the Norwegian healthcare system in the 1970s and 1980s as the result of ‘neoliberal’ ideology. The economic growth in the healthcare sector from the mid-1960s to the early 1980s was enormous. There was broad political support for getting as good health value as possible for the money spent, and, increasingly, cost efficiency became a political goal in itself, alongside equality, equity and social security.Footnote 44 But public health thinking was still very much alive. For instance, in the first half of the 1980s even the centre-right government defended a restrictive policy towards private hospitals to secure the dominant role of public hospitals. Generally, the Labour Party and the Conservative Party agreed about the broad outlines of health policy.Footnote 45 In 1988, the government implemented the World Health Organization’s ‘Health for All by the Year 2000’ strategy in a white paper, with the goal of securing fair distribution of limited resources, especially in an ageing population with increased demands for healthcare. The guiding concept was prevention, the major idea of social medicine, although with an increased focus on the individual and ‘risk groups’.Footnote 46 Nonetheless, the explicit goal of the white paper was equity in health.Footnote 47

3 Health Professionals and Activism in the pre-AIDS Period

In Norway, the prohibition of sex between men was removed from criminal law in 1972, even if there was no tradition of widespread prosecution of homosexual men. A decade later, homosexuality was removed from the list of psychiatric diagnoses by the Ministry of Social Affairs. The decriminalisation and depathologisation of male and female homosexuality were big victories for the gay and lesbian organisations.Footnote 48 Nevertheless, negative attitudes towards gays and lesbians were widespread. At least among psychiatrists, homosexuality was often seen as pathological. For instance, in 1977, when the Norwegian Psychiatric Association, organised under the Norwegian Medical Association, recommended that its members avoid using the diagnosis ‘homosexuality’, the following press release underlined that it would refrain from discussing ‘whether homosexuality should be regarded as a positive or negative way of life, since there obviously are differing views on homosexuality among psychiatrists’.Footnote 49 The association ‘had not taken a stance on the question whether homosexuality is “as valuable” or “as normal” as heterosexuality’.Footnote 50 Moreover, even if the director of the sexological department at Oslo Health Council defended the rights of gays and lesbians and argued against discrimination and criminalisation, he still defined homosexuality as a ‘deviation’ or ‘anomaly’ in his 1979 book for lay people about sexuality and sexual health.Footnote 51 Kirsti Malterud, a lesbian, doctor and activist, recalled that misconceptions about homosexuality were prevalent in the medical community, including among psychiatrists practising ‘conversion therapy’ to treat what they saw as a mental illness. When she travelled to psychiatric hospitals to educate health professionals about sexuality and the specific health problems of sexual minorities, a recurring attitude among psychiatrists was that ‘you can say whatever you like, but we know how we look at these people’.Footnote 52 No wonder, then, that many homosexual people did not seek help, decided not to disclose their sexuality and even travelled across the country to Oslo to see a gay or lesbian doctor even for minor problems.Footnote 53

Hence, even if sexology and sexual liberation imbued the thought style of social medicine, in a paternalistic and heteronormative public healthcare system, homosexuality was still regarded as undesired and pathological. This was also the case in the public sphere. It was in this climate that, in 1975, a group of gay and lesbian health professionals, social workers, lawyers and theologians started an independent consultancy service for gays and lesbians in Oslo organised under the umbrella of gay and lesbian activist organisations.Footnote 54 The activists quickly realised that a considerable need existed for more organised services, and one of them argued in a proposal to Oslo Health Council that even if society had become more open and liberal, ‘prejudices created through generations’ persisted in society.Footnote 55 The professionals at the service saw patients who had met with prejudice or who had been rejected by doctors, and some patients had even been met with ‘suggestions of sublimation’ and attempts to be ‘cured’ either through psychoanalysis or hormonal therapy. Others were simply rejected by the doctors when they disclosed their sexuality.Footnote 56 Many gays and lesbians were forced to live their social life in enclosed ‘free spaces’ like clubs, bars and restaurants. This lifestyle involved high intake of alcohol and a ‘stressful night-life’, which could worsen an already difficult personal situation.Footnote 57 Gays and lesbians easily became a ‘victim of self-condemnation’, which could lead to problems that required help from a healthcare system in which ‘the same attitudes as in the rest of society’ flourished.Footnote 58

As a result, a special counselling service for gays and lesbians, Rådgivningstjenesten for homofile, run by gay and lesbian health professionals, was established in September of 1977 as part of Oslo Health Council – Oslo’s public health authority. The opening of a health service run by doctors, psychologists, nurses and trained social workers allowed queer people to discuss their medical concerns more openly without the risk of facing prejudice or rejection. After one year, the health professionals could draw the following conclusions about their patients: one in four were women; most people were between the age of twenty and thirty-five (even if people aged up to fifty sought help); they presented a mix of social, psychological and medical problems; and seventy-five per cent of them presented some kind of social or sexual problem or problems related to the acceptance of their sexuality.Footnote 59

Malterud, who worked at the counselling service from the beginning, recalled in an interview the important role the service played in educating other professionals and providing information in schools, prisons, hospitals and to the public.Footnote 60 Lacking both professional experience and certified education in gay and lesbian health, combined with a lack of research and academic literature on professional counselling for homosexual patients, the health professionals brought with them their own experiences as gays and lesbians.Footnote 61 No service of its kind existed in Norway or other Scandinavian countries at the time, and, to their awareness, no other public services directed at the gay and lesbian population existed in any European country, except in the Netherlands. Amsterdam’s Schorerstichting, a government-supported mental health service for gays and lesbians founded in 1967, would play a central role in the Dutch AIDS response and become an important model organisation to which workers from the counselling service in Oslo travelled to learn.Footnote 62

It soon became evident to people working in the counselling service that there was an unmet need for somatic healthcare services among gay men: hepatitis B infection, gastro-intestinal parasitic infections, and sexually transmitted diseases like gonorrhoea, chlamydia and condylomas had become a growing part of the epidemiological picture doctors saw in their patients.Footnote 63 Even before AIDS, healthcare workers at the counselling service started to address specific somatic health problems in the gay and lesbian communities.Footnote 64 This coincided with an increased focus on sexually transmitted diseases in the general population. Rates of gonorrhoea increased significantly in the population through the 1970s. Public health authorities ran big information campaigns including boards and TV commercials: ‘You can have gonorrhoea without knowing it’ and ‘Tonight 36 Norwegians will get gonorrhoea. Use a condom’ (Figure 1).Footnote 65

Figure 1: Facsimile from the newspaper Dagbladet 28 June 1979, of a high-profile public gonorrhoea campaign. The poster says: ‘You can have gonorrhoea without knowing. Seek a doctor if you are concerned.’ National Library of Norway, Oslo. Copyright: Dagbladet.

In the 1970s, US health authorities had started to pay specific attention to health problems among homosexual men, particularly sexually transmitted diseases, for example with the national cohort studies of hepatitis B infection and clinical vaccine trials.Footnote 66 In Oslo during the early 1980s, professionals from the counselling service travelled to queer bars to spread information and take blood samples, and the high hepatitis B infection rates among gay men confirmed findings from other large cities.Footnote 67 This realisation led a group of healthcare workers to create a specific service in Oslo directed at the somatic health needs of gay men.Footnote 68 A group of physicians wrote in a letter to the chief medical officer that many homosexual men were asymptomatic, but reluctant to get tested in the regular healthcare system for fear of being outed or of having to disclose their sexual orientation; sexually transmitted diseases would remain unrecognised if patients avoided informing their primary doctors about their sexuality and who they had sex with, the doctors argued.Footnote 69 The gay and lesbian organisations DNF-48 and FHO also urged the health authorities to quickly establish a special health service for gay men, at the same time they underlined that they would reach out to gay men about getting somatic check-ups regularly and organise information meetings.Footnote 70 These initiatives bore fruit. From September 1983, the Health Council offered somatic health check-ups, treatment for sexually transmitted diseases and vaccination against hepatitis B, and the opening of the clinic was reported in the press.Footnote 71 The clinic would serve the population in the eastern and southern parts of Norway, and the health director even approved the notion that, if needed, it could work as an outpatient clinic for the whole country.Footnote 72 Gradually, experienced nurses and specialists in venereology and family care were recruited from other departments in the health council, and close cooperation with specialists in university clinics in the city was established. Two years later, in 1985, the service was turned into a special department for AIDS prevention, the first of its kind in the Nordic countries.Footnote 73 Once again, the initiative came from the queer communities. Gay and lesbian health professionals would prove invaluable in the official responses to the AIDS epidemic, but it did not bring with it an increased attention to lesbian health. Quite the opposite, lesbian health was often neglected, even by the queer organisations. Gay and lesbian communities and queer organisations mobilised, but mostly unidirectionally, in solidarity with gay men.

4 Crossing Communities: Different Kinds of Expertise

Early AIDS activism among medical professionals in Norway grew out of the counselling service for gays and lesbians at Oslo Health Council. Georg Petersen, a general practitioner, public health officer in downtown Oslo and one of the founders of the counselling service, and later its director, played a key role in Norwegian AIDS prevention. Growing up in a working-class family, Petersen knew from a very young age that he was gay, and as a grown-up he appeared to people as ‘a very confident homosexual’.Footnote 74 Friends and people who knew him well described him as a knowledgeable, serious and respected doctor who was loved for his cheerfulness, hospitality and empathy.Footnote 75 He had a clear goal of incorporating family medicine, sexology and social medicine to establish a system where people’s health problems were not seen in isolation, but as part of their identities, communities and societies. He would play a crucial role in developing and promoting a broad concept of gay and lesbian health, including about the negative health effects of living in a heteronormative and homophobic society.

When the first cases of AIDS were diagnosed in Norway in 1983, this came as no surprise to healthcare workers. Before the first cases of AIDS were reported in the United States in 1981, Petersen had visited New York several times with his partner. ‘We were familiar with the subculture’, Petersen recalled.Footnote 76 In the partly autobiographical novel, The Death of Desire? Confessions of a Man of the Gay Generation, his partner, Nils Johan Ringdal, described their experimental lifestyle:

From the second half of the 1970s, Georg Petersen and I systematically travelled to large cities and holiday destinations in the United States and Europe hunting for men and happy days. We visited New York and Berlin, Amsterdam and San Francisco, Mykonos and Ibiza, Key West and Fire Island, and we felt life racing as strongly as Augustin must have felt it in his time.Footnote 77

In the summer of 1981, they moved to New York City, Ringdal as a visiting scholar at Columbia University, Petersen to do a masters in public health and to do research on hepatitis B. From their apartment in Greenwich Village, in the epicentre of New York gay life, they witnessed and took part in a lifestyle and culture filled with sex, drugs and electronic music. Their stay, however, quickly became intertwined with the devastating epidemic. As a physician, student in public health and gay man, Petersen was confronted with the horrors of AIDS professionally and personally. Having witnessed members of his community die and friends perish, he returned to Oslo emboldened by the idea that an efficient response was contingent on engaging and working with the gay communities.

With him, Petersen had Calle Almedal, with whom he had co-founded the counselling service some years earlier. Before becoming a nurse, Almedal had studied theology and lived in a monastery, and explored gay metropolitan nightlife, including experimentation with drugs. Almedal had experienced gay sex culture first-hand: When he visited Petersen in New York City, he sold tickets in one of the biggest bathhouses, where he learned ‘the importance of perfectly manicured nails when fist fucking’.Footnote 78 He also saw the consequences of what was then referred to as GRID (Gay Related Immune Deficiency), and he remembered in an interview that he became obsessed with what he could do as a healthcare worker to prevent a similar situation happening in Oslo. Given that ‘so many Norwegians come here [to New York] and visit the bathhouses, it will happen here too’, he remembered thinking.Footnote 79 In the autumn of 1982, Petersen had just returned from his sabbatical. ‘[W]e became monomaniacally preoccupied by it, at least I did’, Almedal recalled, saying he would call Petersen four–five times a day to discuss strategy in between the operations at the hospital where he worked.Footnote 80

In New York, Petersen had visited the Gay Men’s Health Crisis and several doctors who were engaged in preventive work and dedicated care for gay men and people with AIDS. Given their own experiences from gay communities, Almedal and Petersen became more and more convinced that gay men needed to change their lifestyle, but that this change had to come from within the communities, and that the message needed to be delivered by people who were themselves affected by the epidemic. In a letter to the gay and lesbian organisations, Almedal encouraged the organisations to leave former conflicts behind, as ‘these disagreements are uninteresting as long as AIDS is a disease that efficiently kills those affected’, and to establish a committee to handle the need for information about AIDS and sexually transmitted diseases among their members.Footnote 81 Together with other gay and lesbian activists, Petersen and Almedal founded the first activist gay and health organisation ‘because of the AIDS situation and the recognition that gay men in particular are at risk of sexually transmitted diseases and a will to do something with these conditions’.Footnote 82 The Norwegian Gay Health Committee [Helseutvalget for homofile] founded in 1983,Footnote 83 was modelled on the community-run Gay Men’s Health Crisis and became the gay and lesbian organisations’ coordinating body for AIDS information.Footnote 84 Its statutes stated that the committee would consist of eight members, men and women, of whom at least two had to come from outside of Oslo. One member had to be appointed from the health director’s working group on AIDS (see under), one from the counselling service at Oslo Health Council, three from DNF-48, two from FHO and one from the fetish organisation. It was later decided that all counties should be represented, and offices were founded across the country. Even if it was an explicit goal ‘to work for a general improvement of the health situation of gay men and lesbian women’, AIDS would come to dwarf the special health needs of lesbians.Footnote 85

There now existed two bodies from where AIDS activism emerged: the counselling service and the Gay Health Committee. But the gay and lesbian organisations mobilised too. In October 1983, DNF-48 put together a ‘health plan for AIDS’ to reach out to organised and unorganised gay men. To prevent stigma, all governmental recommendations had to rest on research-based knowledge and provide research to the gay and lesbian organisations and the public. DNF-48, meanwhile, would intensify the information work, but underlined that in every aspect of the prevention work, a close and formalised cooperation between activists, health services and the authorities should be sought.Footnote 86 Important to this story is also the fact that gay health activists and professionals (of whom all were men) managed to get positions in governmental organs hammering out official AIDS policy. Yet it is unclear if the authorities themselves saw the importance of including activists or gay men, at least in the beginning.

In April 1983, the health director received two reports from an AIDS conference in New York: from Stig Frøland, an infectious-disease specialist, and Georg Petersen, who had communicated with AIDS researchers, doctors working with AIDS patients and activists.Footnote 87 Both urged the director to establish an expert group to develop guidelines for diagnostics and therapy of AIDS and monitor and coordinate governmental preventive work. The director ended up transforming the former advisory board on vaccination into an advisory board on preventive infectious medicine [Rådgivende utvalg i forebyggende infeksjonsmedisin – RUFIM].Footnote 88 Under this board, a working group on AIDS was established, directed by a senior doctor at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health who appointed five other specialists in infectious diseases, immunology/transfusion medicine and microbiology – except Georg Petersen, who was appointed as a specialist in ‘information technique and family medicine’.Footnote 89 The health director now had a dedicated organ working on AIDS consisting of highly specialised medical professionals, of whom all were white men. Petersen was the only representative belonging to one of the perceived ‘risk groups’; if he was appointed because of his sexuality and intimate knowledge about and access to the gay communities, that was not stated officially. However, there was no doubt that the director was aware that Petersen was gay. In a letter to DNF-48 about the new working group on AIDS, Mork mentioned only one name appointed to the group: Georg Petersen.Footnote 90 This organ stayed in place until June 1985, when it was reorganised into the health director’s advisory group on AIDS [Helsedirektørens rådgivningsgruppe for AIDS-sykdommen]. Of the twelve healthcare workers appointed to this group, ten were physicians, one nurse and one psychologist. Again, all were white, but this time two women were included. This group, however, had a more dynamic structure, and as new problems and perspectives emerged, new people were appointed, even ‘representatives for HIV-positive people themselves’.Footnote 91 Petersen was included this time, together with Calle Almedal.Footnote 92 Finally, in 1987, when the minister of social affairs established a special group on AIDS [Sosialministerens referansegruppe i kampen mot HIV/AIDS-epidemien], they both sat at the table.

5 Information Work 1: Negotiating Insecurities

One of the earliest most urgent questions for AIDS activists was how to advise communities to prevent people from getting sick. In March 1983, at the time when Oslo Health Council distributed its first information leaflet about AIDS to gay men, the aetiological cause was unknown. The virus, which would be coined as HIV in 1986, was identified in a handful of studies between 1983 and 1984. When the first preventive suggestions were being made – even if the hypothesis of a new infectious agent gained more and more support in medical communities – several aetiological theories were circulating. The medical community was not univocal, and in gay communities the theories were manifold. As Richard A. McKay has shown, many gay men supported the hypothesis that AIDS was the result of several coinciding lifestyle factors, like drug use, partying, unhealthy lifestyles and recurrent sexually transmitted infections.Footnote 93 The first leaflet about AIDS created by Almedal and Petersen demonstrates how difficult it was to provide sound advice when so little was known. In direct language they advised gay men to take responsibility for their own sexual lives: ‘[T]he more sex partners you have, the greater the risk of contracting AIDS’; ‘You should reduce the number of partners, not have less sex’; ‘Avoid anal sex with a random partner. Kiss a lot, but not in the …’; ‘Do not use back-rooms’; and ‘Avoid poppers, and do not drink so much that you forget to give your name and address to the person you have sex with’.Footnote 94 Although the advice left no room for doubt about the severity of the situation, it underlined that there was no reason for panic, and evoked the community spirit and importance of unity: ‘These are simple suggestions we all can follow. … We all have to do what we can to contain it [AIDS].’Footnote 95

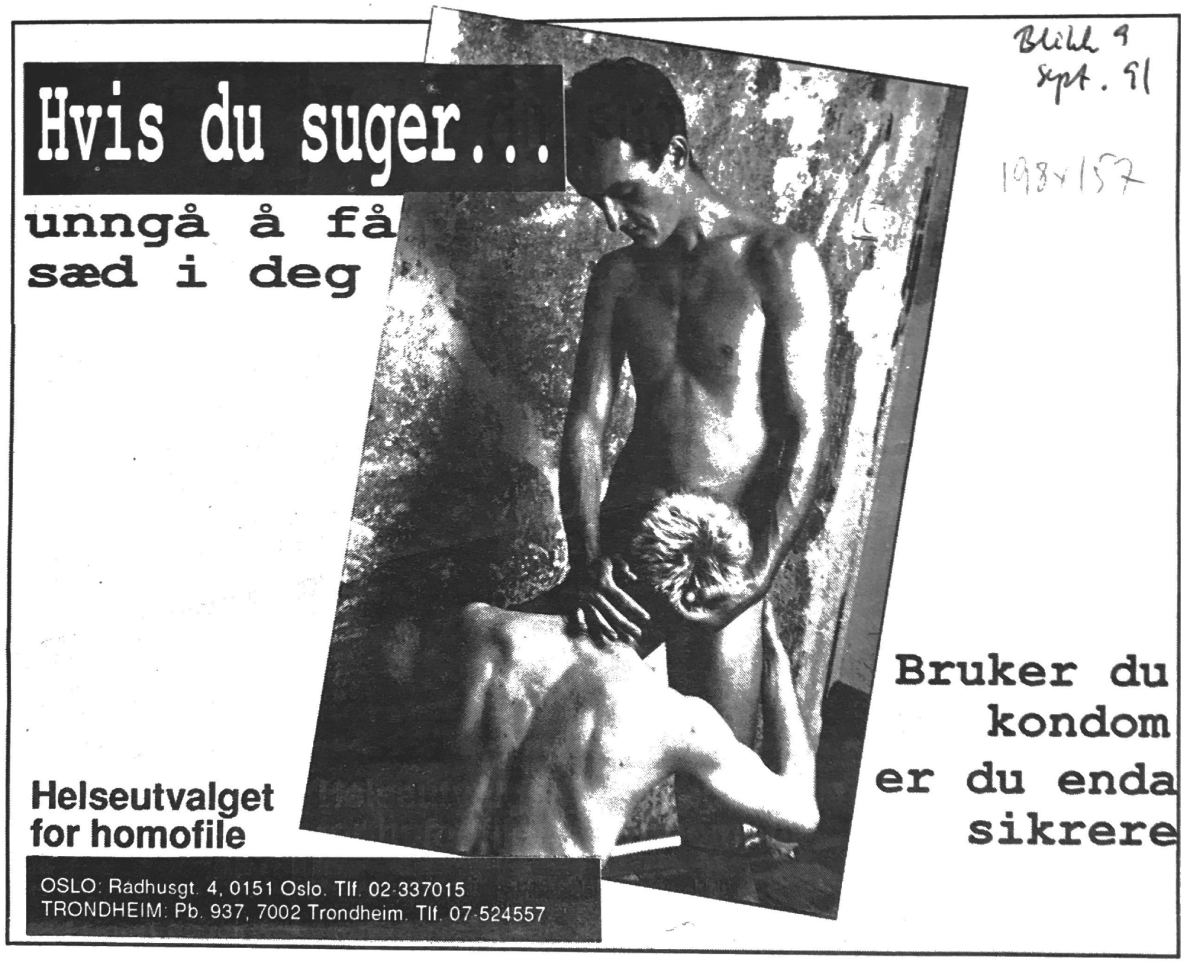

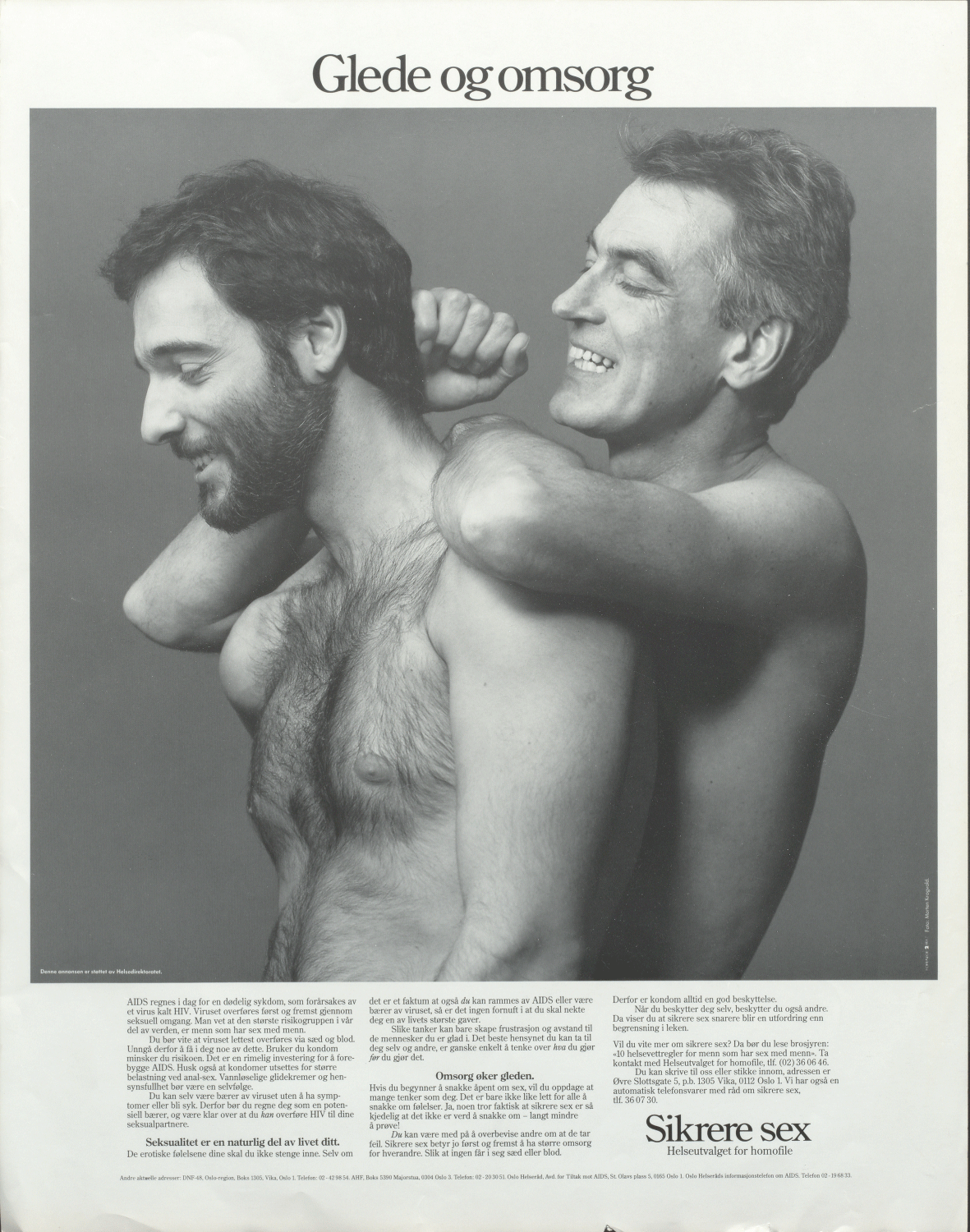

Importantly, however, the first information leaflet did not mention the use of condoms. As the debates in medical journals about condom safety showed, the role of condoms in preventing spread of the disease was contested, even several years into the epidemic.Footnote 96 Information material from the mid-1980s underscored the importance of changes in lifestyle, like reducing the number of sex partners, avoiding anonymous sex (‘always get the name and address of your partner’) and traditional Norwegian public health suggestions such as ‘have a proper diet, exercise and get fresh air’.Footnote 97 By 1985, however, condoms played an important role in the preventive suggestions.Footnote 98 The queer journal Løvetann included small advertisements with statements like ‘Gay and lesbian nurses encourage gay men: use condoms!’Footnote 99 In one information folder, it was stated that condoms are ‘highly recommended for all those who think anal sex is an important part of sex life’.Footnote 100 Activists in the Gay Health Committee deliberately tried to avoid one singular preventive strategy of condom-use. Kjell Erik Øie, a gay man, nurse and AIDS activist who would become the leader of DNF-48 and work for the Gay Health Committee, remembered that the Committee’s preventive work instead suggested one of three approaches: sticking to one partner, celibacy or using condoms.Footnote 101 Promoting condom-use was not unproblematic, especially for oral sex, even if the Gay Health Committee continued promoting the use of condoms for oral sex into the 1990s (Figure 2).Footnote 102 The former leader of the Gay Health Committee recalled in an interview how activists constantly tried to balance the need to provide sound advice to the community while respecting the human need for sex and joy.Footnote 103 For some couples, activists thought, it was possible to stay monogamous and not use condoms.Footnote 104

Figure 2: Safer sex ad from the Gay Health Committee, Blikk, 9 September 1991. The advertisement says: ‘If you give blowjobs … don’t get semen in you. If you use a condom, you’re even safer.’ Skeivt arkiv, Bergen. Copyright: Helseutvalget.

Much less was known about the natural course of infection. In an information booklet for healthcare workers published by the Directorate of Health in 1985, it was assumed that, of people who seroconverted, only four to nineteen per cent would develop AIDS. In twenty-five per cent of those infected, it was thought, the virus would lead to pre-AIDS/lymphadenopathy-syndrome, e.g. suppression of the immune system without clinical significance. However, a large majority, sixty-five per cent, would remain asymptomatic, healthy carriers of the virus.Footnote 105 In the first comprehensive information folder about AIDS for gay men, Petersen rebuked the idea that AIDS was a ‘lifestyle disease’, a gay man’s disease: ‘Coughing is not the cause of influenza’, he wrote, ‘we don’t fight an influenza epidemic by prohibiting coughing, but by encouraging people not to cough directly at one another.’Footnote 106 The folder is a stark reminder of the fact that even if the HTLV-III virus was identified in studies in 1983 and 1984, it still was not clear in 1985 whether the virus was a sufficient factor in pathogenesis, or if other co-factors had to be present.Footnote 107 The immunosuppressive role of other men’s semen, poppers or Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infections could still not be completely ruled out, and the folder repeated the importance of good hygiene ‘before and after sex’, that one should stick to one partner and avoid anal sex or ‘the transference of bodily fluids’.Footnote 108 Even kissing was not without risk, it was thought, even if the risk was much less than for anal sex.

In society and the gay and lesbian communities there was a big need for information, and it did not take long for fairly inexperienced healthcare workers to become experts. But this dual role of being activist and healthcare worker – the very amphibiousness of AIDS activism – posed real problems in a time when little was known about disease mechanisms. Almedal recalled in an interview: ‘One night we were allowed to use Metropol. I remember picking up Georg at the Health Council to have dinner before we were giving a talk and Georg was very nervous. … “How do we do this”, he said, and then said, “we do it like this: I handle the medical stuff and you talk about prevention”’. Almedal he continued laughing: ‘Right, we have no idea what we are talking about, in 1983 we didn’t know much, how are we supposed to talk about prevention then?’.Footnote 109

6 Blood Banks: How to Communicate a Message

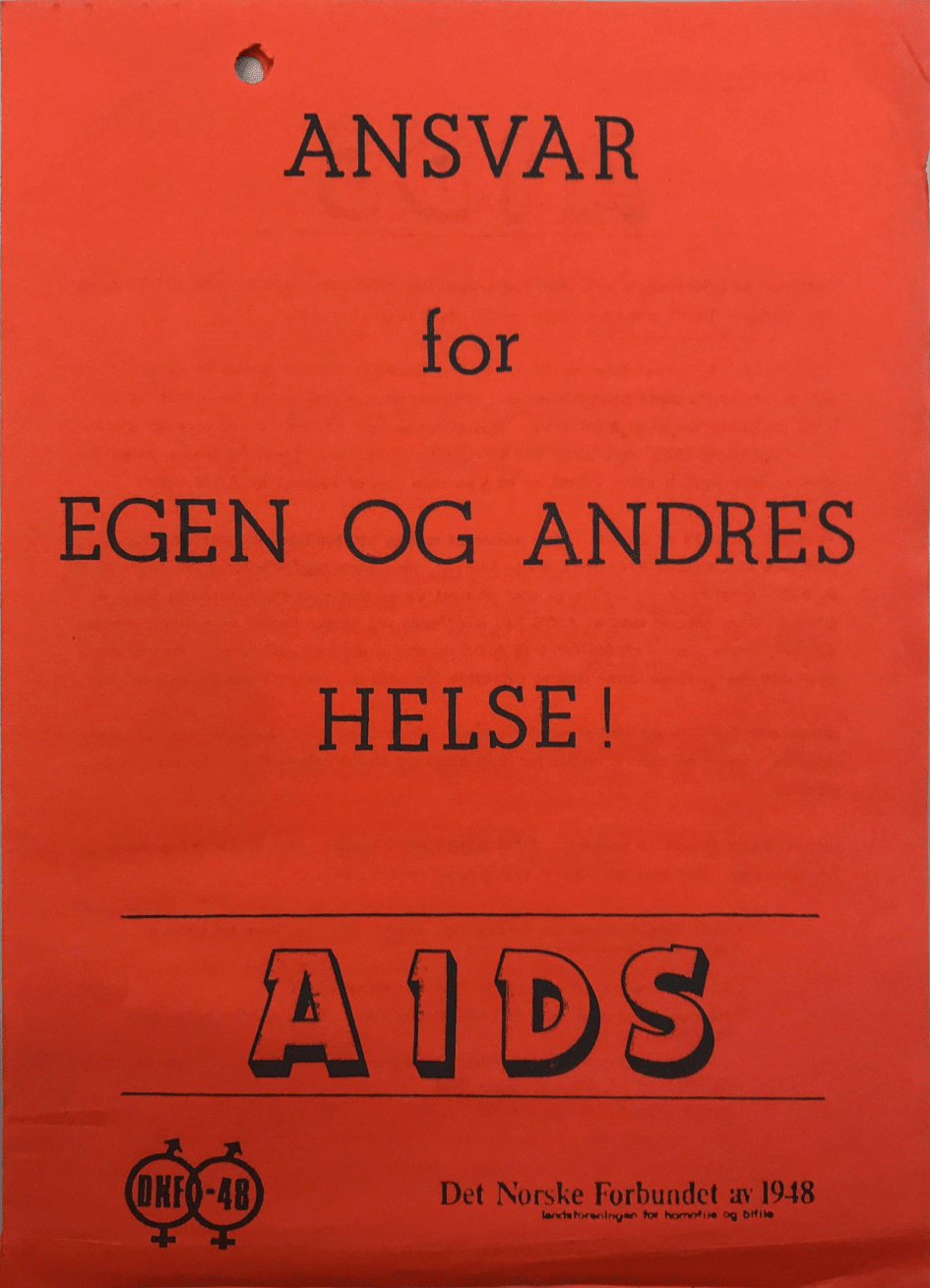

Early AIDS prevention work was mostly done by activists on a voluntary basis. In the early years of the epidemic, AIDS activists found little support in the authorities: ‘Nobody wanted to listen to us. The Directorate of Health showed little interest and they didn’t have any money’, the leader of the Gay Health Committee said in an interview.Footnote 110 One of the earliest public information meetings about AIDS organised by activists took place in the early months of 1983 at Metropol in Oslo, a restaurant and night-time venue for the queer community. Over 150 people attended what was described by some as the biggest meeting to ever take place there. Under the motto ‘Responsibility for your own and other people’s health!’, Almedal and Petersen informed the primarily gay male audience about AIDS. One crucial message was that they should refrain from donating blood; importantly, people were encouraged not only to take care of their own health but to think about the community, protecting each other (Figure 3).Footnote 111

Figure 3: The likely first Norwegian information folder about AIDS, dated 4 March 1983, written by Georg Petersen and Calle Almedal and produced by DNF-48. The title page says: ‘Responsibility for your own and other people’s health!’ Skeivt arkiv, Bergen. Copyright: Helseutvalget/Fri – foreningen for kjønns- og seksualitetsmangfold.

It was not the first time that gay men had heard this message. In the autumn of the year before, a gay activist group called Gruppe Lambda had informed the gay community about the importance of abstaining from donating blood until more was known about the new disease,Footnote 112 and FHO and DNF-48 encouraged gay men ‘who had had especially numerous sex partners last year’ to refrain from giving blood.Footnote 113 According to DNF-48, for many people, including gay men, donating blood was a way of having their blood checked for diseases like hepatitis B without having to disclose to the doctor who they slept with or their sexual orientation.

At that time, the evidence of transmission by blood was inconclusive. In the first month of 1983, less than a dozen cases of AIDS had been reported in people who had received blood products in the United States.Footnote 114 When Petersen reported back to the Norwegian officials three months later, from an international AIDS conference in New York City, he underlined what an expert had said, namely that ‘none of the cases [of AIDS] could be related to blood transfusion with 100 per cent certainty’.Footnote 115 A joint statement of the United States blood banks with other organisations underlined that the possibility of blood transmission should lead to additional precaution in the use of blood products and that attempts should be made to limit blood donation from ‘individuals or groups that may have an unacceptably high risk of AIDS’.Footnote 116 One way to do this was to screen the donors for symptoms of AIDS, like night sweats, unexplained fevers and lymphadenopathy. Another was to prohibit gay men from donating blood. The blood banks’ statement advised against this latter approach, however, because asking direct or indirect questions about a donor’s sexual preference would be inappropriate: ‘Such an invasion of privacy can be justified only if it demonstrates clear-cut benefit.’Footnote 117 Such an intervention might also prove inefficient, because there was ‘reason to believe that such questions’ were ‘ineffective in eliminating those donors who may carry AIDS’.Footnote 118 Blood banks, instead, were to cooperate with gay organisations to prevent donations by gay men.

During the spring of 1983, the health authorities took their first steps in creating a Norwegian prevention strategy. They believed that, instead of discriminating against vulnerable groups, such as gay men, when donating blood, the groups should be informed by community organisations about the disease and encouraged to abstain from donating blood until the aetiology and way of transmission was understood.Footnote 119 In January 1983, on the initiative of its doctors, the main blood bank in Oslo made donors fill out a questionnaire that explicitly stated that gay men with many sex partners should refrain from giving blood.Footnote 120 DNF-48 disapproved of this strategy, and ultimately the head of the blood bank was summoned to the health director’s office and the hospital was made to change the questionnaire and its routines. The official guideline on blood donation, which was sent to Norwegian hospitals a month later, in April 1983, reproduced the Centers for Disease Control’s so-called ‘risk groups’: sex partners of people with AIDS, sexually active gay and bisexual men with many sex partners, former and current users of injectable drugs, people with haemophilia and immigrants from Haiti.Footnote 121 These groups – constructed on the basis of sexuality, nationality or disease, as opposed to practice – were teleported to Norway:Footnote 122 ‘[B]oth in theory and practice the same groups at risk of transmission are to be expected.’Footnote 123 A circular underscored that donors should get information about AIDS and who was at risk. Donors belonging to a risk group should not donate blood and had to sign an information letter. In hindsight, the health director’s strong reaction towards the hospital that had implemented its own system while waiting for officials to act seems puzzling. The decision, however, mirrored the situation in the Netherlands, where blood banks initially wanted to exclude all gay men from donating blood, spurring the authorities to summon representatives from the blood banks, the haemophilia organisations and the gay and lesbian movement. They eventually ended up not excluding all gay men, but instead having gay and lesbian organisations tell members of the communities that gay men should abstain from donating blood.Footnote 124

The debates around decriminalisation of sex between men and the recent removal of homosexuality as a psychiatric diagnosis might have been fresh in the minds of officials. Even if there was a long tradition of integrating a liberal philosophy towards sexual health in the policy of the Directorate of Health, being openly gay or lesbian was still highly stigmatised in society, also in the public healthcare system. Even if the questionnaire did not specifically ask the donors to specify whether they were gay or not, it could indirectly identify them if they abstained from donating blood after checking ‘no’ in all the other boxes for risk factors. The authorities probably included gay activists and gay organisations in the preventive work to create an official response that was sensitive to possible discriminatory effects of suggestions and interventions. The message was repeated in 1985, in a statement from the Gay Health Committee signed by Almedal, that ‘men who have sex with men should not donate blood’.Footnote 125 Ultimately, the way the message was delivered and by whom was as important as the content of the message itself.

7 The Problems of Testing the Many

Professional opinions differed about how to best contain the epidemic. One of the most controversial topics was whether people should be tested against their will. Again, the battleground was the blood banks. Even if some testing options had been available for use in hospitals since late 1984, the antibody tests, which became commercially available in Norway during the spring of 1985, radically changed the epidemic in several ways. It now became possible to get completely new epidemiological overview of the epidemic, and the tests allowed members of risk groups to go from being per se targeted to actually having a definitive answer to whether they were infectious. They changed individual lives and their temporalities, present experiences and expectations for the future, in particular for a new group of people who were future ill but still not sick. The tests also provided new tools for the government to target preventive interventions.

In several countries, the tests spurred discussions about how far the government should go to test the population, if necessary, against their will.Footnote 126 From an early point in the epidemic, directors of the Norwegian blood banks advocated testing all blood donors. Already around the turn of the year 1984, a medical microbiologist returned from the United States with an immunofluorescence test that showed that several Norwegian patients with haemophilia had developed antibodies against the virus. This was the first time that infection through blood donations was demonstrated in Norway. Doctors immediately contacted the health director to recommend the urgent implementation of screening of all blood donors.Footnote 127 The director rejected the proposal, but directors of blood banks had secretly implemented routine screening of blood, and when the HTLV-III virus was detected in donor blood in the summer 1985, it caused outrage in Norwegian newspapers and led to much criticism of the reluctant official policy.Footnote 128 The head of one blood bank called the health director’s decision ‘unbelievable!’, sarcastically adding that it meant that ‘in the meantime blood donors with AIDS should be able to donate as much blood as they want’.Footnote 129 How could the director’s position be understood? Why was he reluctant to implement mass screening of blood?

There were, first of all, inherent problems with the tests and mass testing in general, including a risk of false positives. The directorate was wary because it was unclear whether the sensitivity and specificity was good enough and whether there was enough competence and equipment available to be able to conduct the tests. Second, and more importantly, the director asked whether there was a system in place to take care of those who tested positive: the healthcare system had to be able to ‘follow, advice and take care of seropositive patients, and be able to handle psychosocial problems’, the control programme for AIDS stated.Footnote 130

Serological testing should not be started until the necessary systems were in place to take care of those whose test returned positive. The officials worried that implementing testing practice too early could have counterproductive effects: ‘Experience has shown that testing without a system for follow-up can lead the clients to increase their destructive behaviour, intravenous drug use, prostitution [sic] or irresponsible sexual conduct. There also are examples of suicide and suicide attempts.’Footnote 131 Testing the blood in the banks before testing services were available elsewhere could lead people to donate blood to get tested, and, as already mentioned, this was a widespread among gay men. That would pose a big threat to the donation system. In August 1985, the health director informed all county medical officers that screening of donor blood would be implemented and that they had to make sure that proper follow-up for people who tested positive would be provided.Footnote 132

Two other issues underscore the divergent stances on prevention among doctors: the notion of coercive testing or testing behind people’s back, and the idea of mass testing the population. Many physicians saw it as an undue interference in their professional decision-making to be told when to take a test or not, and argued that it should be a medical decision.Footnote 133 The Directorate of Health, on the other hand, stated that all patients tested for HTVL-III had to be informed when they were tested, though this position was later moderated to some degree, so that testing as part of a medical examination did not require the patient’s consent.Footnote 134 Some doctors also advocated testing the whole population. ‘Is it considered good “modern” epidemiology to risk the health of the population by trusting the risk groups’, the head of a blood bank wrote in an open letter to the health director, demanding that the whole population be tested twice a year.Footnote 135 In an opinion-editorial in a national newspaper, Georg Petersen repeated his belief in the voluntary philosophy. False positive results would ‘create sleepless nights for many people and maybe also ruin a harmonious marriage’. He argued that those assumed to be most prone to infection, with whom the officials and the health services had established an efficient cooperation, would likely be scared away by the use of coercive measures.Footnote 136 Former studies on screening had shown that around ten to twenty per cent of the population did not show up for testing.Footnote 137

Living with AIDS was highly stigmatised on several levels of society. Very few people were publicly open about their illness, and officials perhaps had the discussions about testing that had been taking place in US gay organisations fresh in their minds. In the US, activists and gay organisations had advised gay men not to get tested. In 1984, the New York Native, a high-profile gay newspaper, recommended that gay men abstain from getting tested, since ‘the meaning of the test remains completely unknown’.Footnote 138 What was certain, the newspaper argued, was the ‘personal anxiety and socioeconomic oppression that [would] result from the existence of a record of a blood test result’.Footnote 139 The test results could potentially have detrimental effects: ‘Who will be able to keep this list out of the hands of insurance companies, employers, landlords, and the government itself?’Footnote 140 A Gay Men’s Health Crisis poster from 1985 stated ‘The test can be almost as devastating as the disease’ and went further in advising gay men to refrain from getting tested.Footnote 141 In Norway, too, some people who tested positive lost their jobs.Footnote 142 Insurance companies rejected applications for life insurance among HIV-positive people,Footnote 143 and gay organisations and activists recommended gay men get insurance before taking the test.Footnote 144 Many people argued that the test result would not change the lives of the people affected anyway: no cure was in sight and everybody had to live as if they were infected regardless. In the United States, AIDS organisations eventually landed on a consensus of anonymous testing.Footnote 145 Norwegian authorities feared there would be a polarisation between gay and bisexual men and their organisations on one hand and the public health authorities on the other, as there had been in the United States. In a book for lay people, Georg Petersen encouraged gay and bisexual men to get tested, but for that to happen they ‘must continue to trust the public healthcare system and politicians. But if the debate about coercive measures grows and more people lose their jobs and houses even here, we can expect the situation to become more polarised and politicised, and the fear of getting tested will increase’.Footnote 146 The polarisation he feared was not just hypothetical. ‘We continue to receive messages about doctors in hospitals, outpatient clinics, and other health institutions who perform coercive HIV antibody testing of their patients’, the Gay Health Committee wrote in a letter to gays and lesbians in October 1986, referring to testing being carried out behind the patients’ backs or doctors’ refusal to treat a patient unless he or she got tested.Footnote 147 The activists recognised that healthcare workers could have a legitimate reason to be afraid of infection, but the testing practice was more often rooted in ignorance, since all blood and secretions from all patients had to be handled as potentially contagious and, more importantly, a negative test result did not mean that the person was not infected. Furthermore, they argued that some healthcare workers had a ‘widespread distrust and suspicion towards the health authorities accusing them of being more concerned with protecting the risk groups than the risk of healthcare workers to get infected’.Footnote 148 ‘Norwegian doctors are about to destroy the test as an efficient tool in the fight against AIDS’, they continued, ‘which can undermine the confidence in the healthcare system among people in the risk groups.’Footnote 149 Norwegian gay and lesbian organisations also encouraged people to get tested, while arguing that anonymous testing should be available.Footnote 150 ‘Coercive testing must not discredit the positive effects of HIV testing’, they argued, underlining that the person’s ‘motivation for testing is the decisive factor!’Footnote 151

The health authorities argued the importance that if those who had increased risk of being infected were to get tested, they maintain trust in the healthcare system.Footnote 152 Although a negative test result represented a golden opportunity to discuss safer sex and provide personal information, the antibody test was not to be seen as an efficient preventive measure in itself. The Directorate of Health argued that coercive testing was a brutal and dramatic measure, violated people’s integrity and did not create the positive cooperative relationship needed between the patient and the physician. Furthermore, it maintained, it would mark a bad beginning for the ‘intimate cooperation needed in information-outreach work and the continued process of preventing transmission’.Footnote 153 Instead, the test needed to be branded as a ‘positive health measure for the individual based on voluntarism and cooperation’.Footnote 154 This chapter of Norwegian AIDS history in many ways resembles Australian policy, where communities were given big responsibilities for preventing transmission in lieu of coercive measures.Footnote 155 In Norway, testing practice remained voluntary. Activists in the Gay Health Committee continued reaching out to county medical officers across the country to ensure that people who tested positive would be secured a ‘psycho-social follow-up programme’ including counselling and information by medical personnel and support groups based in the gay and lesbian organisations.Footnote 156 Importantly, even if the medical professionals and authorities argued that testing was based on consent and a voluntary approach, this was not the experience of everybody. ‘When I got the HIV diagnosis by Georg [Petersen] early in 1985, my closest relatives and I were thrown into it’, the gay activist Dag Strand Nielsen wrote in an article in 1994 titled ‘When a doctor looks back’, a stinging critique of Petersen’s recollection of the history: ‘Without consent, discussion, or counselling a frozen blood sample was tested for HIV. … Was this not an example of coercive testing?’Footnote 157

This period in history also illustrates the crucial role played by the Directorate of Health in hammering out policy and in responding to the AIDS crisis. The health director was much more visible in the public debate than his chief, the minister of social affairs. The health director became the conductor of the official political and medical response to AIDS, invoking the long tradition of social medicine and a paternalistic physician-led health bureaucracy. His style of leadership, powerful position and decision to follow a policy based on inclusion and cooperation was harshly criticised, by the former minister of justice among others. In an interview, she encouraged the minister of social affairs to ‘call the Health Director Torbjørn Mork to account and demonstrate who is the head of the ministry’.Footnote 158 This chapter of history demonstrates that, in a time of crisis, the long traditions and structures of public health were mobilised to respond.

8 Information Work 2: The Many Faces and Banners of Activism

In 1985 a shift took place in the governmental organisation of the AIDS work as the health director put together a small AIDS team working under his command, led by a physician. One member of the team recalled how they worked as an enclosed group with direct access to the director ‘We had a lot of money. For instance, we had computers before everybody else in the directorate.’Footnote 159 The directorate funded the Gay Health Committee, and the establishment of the AIDS team also led to a much closer cooperation between authorities and activists. ‘[I]n 1985, DNF-48, the Health Council and the Directorate of Health travelled together on a 10-day research trip to New York’, the former leader of the Gay Health Committee recalled, and continued: ‘We learned a lot about AIDS and about each other. This started everything in Norway.’Footnote 160 As activists continued to work in the communities, they also worked alongside government partners, at the same time as authorities explicitly sought a close cooperation with the affected communities and their organisations. This cooperation was often mediated by involved healthcare professionals. Norwegian AIDS work involved a myriad of formal and informal working groups and networks, and continuous personal contact between officials, gay and lesbian health professionals and activists, and the communities themselves.Footnote 161 The way people working in the AIDS team remembered it, it was ‘completely uncontroversial’ for the authorities to cooperate with the gay and lesbian organisations, especially since they were represented by gay and lesbian physicians and nurses.Footnote 162 One person recalled how she would just pick up the phone and call the leader of the Gay Health Committee to make sure information and measures were suited for the affected communities they were developed for.Footnote 163 For the AIDS team, it was crucial to ‘follow the virus’ to make sure that the measures would work. To make sure that the interventions would be efficient, they needed detailed information about how people actually had sex, and they required credibility and trust in the affected communities to succeed with their strategy.

Even if some gay healthcare workers ended up having official positions in preventive AIDS work, the initial initiatives started as grass-roots activism in different parts of the country. In Oslo, AIDS spurred activism among gay and lesbian general practitioners who more broadly wanted to protect their communities.Footnote 164 In Trondheim, Norway’s third biggest city, gay health workers also played a pivotal role in early non-governmental preventive AIDS work. There, in 1985, a gay activist and general practitioner, working with a gay nurse, started offering HIV testing on a voluntary basis. A year later the service was expanded into a public clinic with a psychologist and social worker, providing testing services, contact-tracing, hepatitis B vaccination and ‘medical and psychological support’ to asymptomatic HIV-positive people.Footnote 165 In cooperation with the gay and lesbian organisations, they organised information meetings for the gay community and developed information material about safer sex.Footnote 166 The gay and lesbian organisation in Bergen, Homofil bevegelse i Bergen, was led by two gay men and medical students. The leader recalled that this amphibious position gave them credibility ‘both to use what we learned in medical school but also to influence the curriculum’.Footnote 167 ‘We engaged with the Department for infectious diseases in discussions and tried to cooperate with the departments for infectious diseases and dermatology and venereal diseases which did much of the HIV testing in Bergen.’Footnote 168

Another example reflecting the increasing cooperation between the communities and officials was a large-scale 1986 information campaign. An information brochure developed by the Gay Health Committee used explicit language to give suggestions about safer sex for men who had sex with men.Footnote 169 These included avoiding rimming and getting semen in one’s mouth and being cautious if using sex toys with urine on them. The illustrations were humouristic, mirroring activist efforts in San Francisco. A big effort was made to tailor the advice to the subcultures without doing harm. It was important to show that sex could be ‘fun and good’. The Gay Health Committee had a range of tools in its prevention kit: safer sex seminars for gay men in hotels with paid lodging (where participants were told to jerk off with a condom and talk about it after), safer sex workshops with overhead instructions of where to ejaculate safely and group meetings whose assigned homework was to jerk off in a condom to learn how condoms worked and felt.Footnote 170 They also established an anonymous information hotline and automatic answering machine with information about safer sex (the Norwegian Red Cross had Wenche Foss, one of Norway’s most famous stage actresses at the time, record a message about safer sex that explained, for instance, that AIDS was not contracted through sharing toilet seats).Footnote 171 A lesbian activist working in the Gay Health Committee recalled that, in the late 1980s, activists increasingly started working on outreach prevention work at grass-roots level in bars, clubs and saunas in the Stop AIDS project.Footnote 172 ‘It was a different way of working … We had the Virus group create a show for gays and organisations across the country, financed by the Committee. They were dressed up as stewardesses, and you know before take-off they demonstrate security measures etc. so they demonstrated how to practise safer sex.’Footnote 173

The strategy laid out by the activists would later be referred to as harm reduction and would be a philosophical foundation for the official Norwegian AIDS strategy: priority was given to the individual and his or her situation in relation to others, the communities and society. Instead of giving totalising advice or demands, a preventive programme was to be developed that would speak to people with different needs and desires, so that everybody could be empowered and learn something to protect their bodies and health. This was a new way of thinking about public health and of putting social medicine into action. Even though social medicine and sexual health had been a leitmotif of the health director, in many ways, the postwar healthcare system and public health thinking were paternalistic and directed from the top down. AIDS changed this, as the government was forced to work with communities, making the authorities rethink preventive health. This new approach shared some resemblances with more general changes in public health thinking in the UK, where the ‘health promotion paradigm’ in the 1980s and 1990s ‘began to challenge the dominant public health approach characterised by a patronising and patriarchal medical establishment’.Footnote 174 In the Norwegian AIDS policy, harm reduction and grass-roots activism represented a new approach to social medicine in action. It involved a lot of experimenting and learning along the way, but with the objective of empowering and involving target groups.

Prevention work had to be creative and playful while underlining the need to change sexual habits. To refrain from everything fun and pleasurable would only cause stress, which could then weaken the immune system. The biggest challenge to gay men in the 1980s was the fact that ‘we have to use our fantasy to develop sides of ourselves which we have neglected, and maybe refine the parts of our sex life which are not particularly risky’.Footnote 175 ‘[W]e have to learn to limit our actions’, a gay activist and nurse working at the counselling service told a queer magazine, while emphasising that AIDS should not ‘take away eroticism and joy of life from gay men’.Footnote 176 People would only change their behaviour if they had positive role models. The success of preventive work hinged on building self-esteem and ‘creating a positive image of our subculture’.Footnote 177 The strategy was coined as three Ks: kjærlighet (love), kunnskap (knowledge) and kondom (condom).Footnote 178

Nonetheless, it was not always easy for the gay health activists to balance a sex-positive and non-stigmatising message that respected the fundamental human need for sex and intimacy with their desire as health professionals to provide sound medical advice. A physician and activist remembered initially being sceptical: ‘How do you go into the forest and talk about prevention behind a tree when people are there for cock? That was a big challenge, but I was wrong. … I think there was something about showing respect, and they didn’t distinguish between us and them, but showed that they also were part of it.’Footnote 179 Early on, the harm reduction approach met much resistance among gay men. One information folder for men who had sex with men encouraged people to ‘save the long and wet deep kisses to the one you love the most!’, as French kissing was thought to contract diseases.Footnote 180 One activist remembered in an interview that ‘this was a useless message. … And we said that we cannot have it this way because it might be that the person you love the most actually was infected’.Footnote 181 In early 1983 a physician present at a public meeting, where Petersen and Almedal informed the gay community about AIDS, said that a nurse should not ‘come here and tell me how I should fuck’, a comment which also points to the long tradition of arrogant positioning of doctors above nurses in medical hierarchies, giving primacy to doctors’ knowledge and advice.Footnote 182 Almedal recalled that another gay activist who was present at the gathering described the meeting as being punched in the stomach over and over again.Footnote 183 According to Pedersen, there was ‘a lot of resistance on the first meetings we had at Metropol’.Footnote 184 Another activist described one of the meetings as ‘a hell’: ‘People were furious and scared to death.’Footnote 185

Some gay doctors and activists endorsed a more explicitly sex-positive message, which resonated well in the community: ‘[I]t would be unrealistic to believe that our former strong needs for excitement no longer exist’, a physician and activist wrote in 1987.Footnote 186 ‘We need to take these needs seriously and find ways of satisfying them in supportable ways.’Footnote 187 Other activists were critical of gay and lesbian liberation having become too negative and focused on problems, and saw this as a result of Oslo’s domination of activism: ‘Oslo has been known as the gay metropolis … Oslo’s politics have been the politics of the country’, the leader of the gay and lesbian activist organisation in Bergen wrote (Figure 4).Footnote 188 ‘Bergen is, at the moment, probably the main centre for the rethinking of queer politics and creativity’,Footnote 189 he continued about their efforts to break with negative thinking: ‘We see it as a bigger threat to die from the lack of love than AIDS. And we say that in full responsibility.’Footnote 190

Figure 4: Poster of a sexually suggestive version of the Norwegian flag illustrating an article in Løvetann about sex-positive AIDS activism in Bergen. Skeivt arkiv, Bergen. Copyright: Løvetann/Skeivt arkiv.

The discussions also point to the difficulties of combining the position as healthcare worker and activist: ‘People were angry that we told people how they should live their lives. We were told that the main problem was that people had too little sex, not too much, because people were not open and could not express their sexuality. We shouldn’t become the organisations that advocated monogamy.’Footnote 191

The close cooperation activists sought with the health authorities sometimes challenged their credibility in the communities: ‘People told us that we were in the pocket of the health authorities, that we were bought and paid for, that we were given fancy computers and desks and were invited to expensive seminars.’Footnote 192 As Virginia Berridge has demonstrated, some UK activists remained suspicious of working too closely with the state, as co-operation could imply co-option and incorporation with ‘the compromises around gay identity which were thereby imposed’.Footnote 193 In Norway, too, the wearing of many hats posed difficult dilemmas for gay health activists. One AIDS activist and physician recalled how activists gathered in the apartment of Georg Petersen and his partner when AIDS came. Among other things, they talked about how to create efficient measures ‘without killing the gay lifestyle but with respect for what gay men had been doing’.Footnote 194 Nevertheless, it was important to the activists to demonstrate ‘responsibility’: ‘Of course, it is not easy to establish more respect in society for cruising and Frogner Park and nightlife culture. There wasn’t that much seriousness to point to.’Footnote 195 Perhaps demonstrating ‘respectability’ became particularly important to activists in an egalitarian but heteronormative and fairly conformist society, the country of the Law of Jante? The story at least demonstrates how important and difficult it was for activists to balance between showing regard for their culture and communities on the one hand and demonstrating ‘responsibility’ to get support of the government and sympathy of society on the other. Furthermore, even if sexual health was an integrated part of the thought style of social medicine, it often tended to be heteronormative and not directed at the lives and health needs of queer people.