Depuis vingt ans, j'habite dans une ville nouvelle, à quarante kilomètres de Paris, Cergy-Pontoise. Auparavant, j'avais toujours vécu en province, dans des villes où étaient inscrites les marques du passé et de l'histoire. Arriver dans un lieu sorti du néant en quelques années, privé de toute mémoire, aux constructions éparpillées sur un territoire immense, aux limites incertaines, a constitué une expérience bouleversante. (Annie Ernaux, Journal du dehors, 1993)

The notion of memory has been the subject of numerous discussions in the humanities, particularly in the history and archaeology of antiquity. The aim of this paper is to use this notion, with its different facets, to approach the way a newly founded city built its memory over time through the shape of its street network, the accumulation of monuments and practices, looking at the example of ancient Timgad.Footnote 1 I will focus on one aspect of the built environment: the streets and spaces that surround them, the way in which certain places maintain the memory of the city and of its topographical development, and how everyday urban practices may have maintained this memory.

The choice of Timgad as a case study is explained by the large number of remains uncovered and the possibility of immersing oneself in an urban landscape at human height. Even though no stratigraphy allows us to provide a precise chronology of the city's development, the abundance of epigraphic material associated with numerous public buildings enables us to reconstruct an image of the city at a given period. In order to work on the notion of memory, it was necessary to select a period in which this foundation ex nihilo already had a past that could be perceived as such: the new city is by definition ‘deprived of all memory’, to use the words of Annie Ernaux.Footnote 2 In Antonine Timgad, it is difficult to work on the collective memory insofar as the foundation of the city, less than a century before, and its first developments can still be preserved in oral history and family memories (Assmann Reference Assmann1995, 127). Late Antiquity, which has obviously been the subject of numerous studies on these matters, presents even different problems (Kristensen Reference Kristensen, Sami and Speed2010). The state of Timgad analysed here corresponds to that of the mid-third century AD (Figures 1 and 2), shortly after the reign of the Severan dynasty, during which the city, like many others in North Africa, expanded and was equipped with numerous buildings.

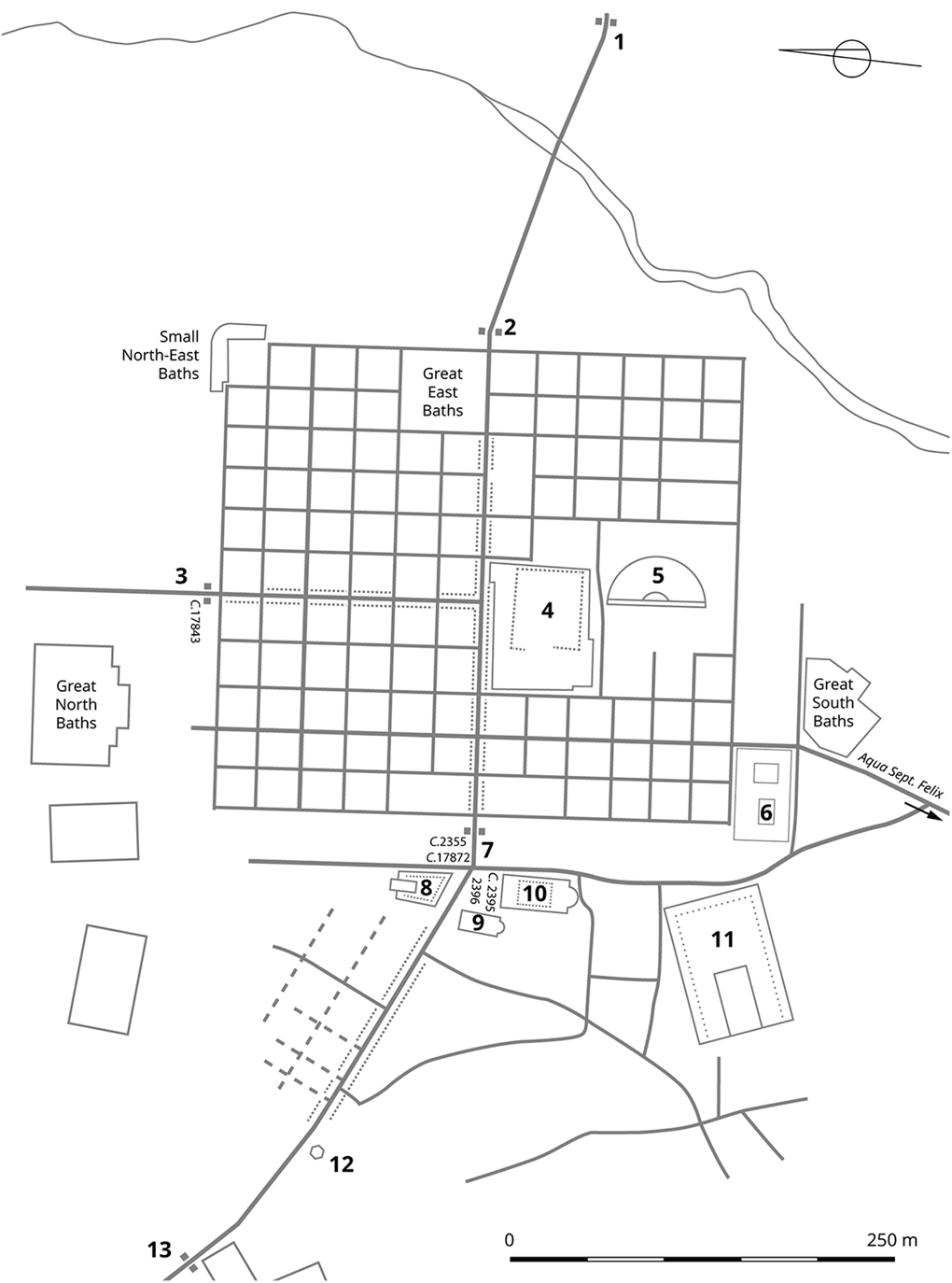

Figure 1. Timgad, plan of the city, ca. mid-third century AD with main monuments (image N. Lamare). 1: Outer eastern gate (Gate of Lambaesis); 2: Eastern gate; 3: Northern gate (Gate of Cirta); 4: Forum; 5: Theatre; 6: House of Sertius; 7: Western gate (‘Arch of Trajan’); 8: Temple of the Genius Coloniae; 9: Basilica vestiaria; 10: Market of Sertius; 11: Capitolium; 12: Fountain of Liberalis; 13: Outer western gate (Gate of Lambaesis).

Figure 2. Timgad, vertical aerial view – MV134, May 27, 1953 (© Service Historique de la Défense, Vincennes – Fonds CEIAA).

After a presentation of how the notion of memory has been used in the study of antiquity, I will deal with three specific aspects of memory in the urban space. Firstly, I will analyse the way in which urban development was materialized in the construction of different arches, and how these served as topographical and memorial landmarks in the city. I will then study the orthogonal plan so characteristic of Timgad to highlight its survival over the decades and the symbolic meaning that linked it to the date of the city's foundation. Finally, I will address another aspect of memory, the individual memory, constructed by the individuals themselves based on the built environment, which enabled them to find their way around the urban space and to understand it, while at the same time creating an image of their city.

Memory and the ancient city

Several notions have been developed concerning memory. The work of Maurice Halbwachs (Reference Halbwachs1994, Reference Halbwachs1997) defined collective memory around two aspects: firstly, individual memory is influenced by social frameworks, and secondly, it is the memory of a group in a given culture, which means that there are as many memories as there are groups. A related notion, also proposed by Halbwachs and developed subsequently, is that of social memory, which is the expression of a collective experience, identifying a group, giving meaning to the past, and defining the aspirations of the future (Fentress and Wickham Reference Fentress and Wickham1992; Rous Reference Rous2019). The most important alternative to these notions is Jan Assmann's cultural memory (Assmann Reference Assmann1992; Galinsky Reference Galinsky2014, Reference Galinsky2016; Galinsky and Lapatin Reference Galinsky and Lapatin2015). It is distinguished from communicative or everyday memory, already developed by Halbwachs, which is constituted by everyday interactions between people belonging to a group that conceives its unity and specificity through a common image of its past. In contrast to this memory, which is characterized by its proximity to everyday life, cultural memory is defined by its distance from it: it has a fixed point, its horizon not changing with the passing of time. Assmann (Reference Assmann1995) identifies these fixed points with decisive events of the past, the memory of which is preserved in cultural formation (texts, rites, monuments) and institutional communication (recitation, practices, observance), which he calls ‘figures of memory’.

Whichever concept of memory one uses, many of the characteristics of each of these concepts overlap and are superimposed; one would even suggest that distinguishing them is neither relevant nor helpful for the study of antiquity (Gallia Reference Gallia2012, 3–4; Gowing Reference Gowing2005, 8–9). Similarly, these memories at the same time develop through and give rise to several mediums, material or immaterial. The oral transmission of communicative memory is an essential aspect of Halbwachs’ definition; historiography and the preservation of documents by institutions, i.e. archived memory, complete it. The lieux de mémoire, defined by Pierre Nora (Reference Nora1984), incorporate much broader metaphorical notions but also spatial and material elements. Doubts have been expressed about the validity and relevance of applying this latter concept to Roman antiquity (Siwicki Reference Siwicki2019, 12–13).

The idea of materiality is essential, including and especially for my purpose. Halbwachs’ argument was that memory is located in objects and places. His argument aside, we now consider the material framework of memory, i.e. the way in which monuments and landscapes determine social remembrance (Alcock Reference Alcock2002, 28–32). In the Roman world, spaces, places, and monuments of all types (buildings, statues, and texts in situ) played a key role in the preservation and transmission of memory (Hölkeskamp Reference Hölkeskamp, Rosenstein and Morstein-Marx2006; Benoist et al. Reference Benoist, Daguet-Gagey and Hoët-Van Cauwenberghe2016). Furthermore, the construction of memory takes place in everyday life, incorporating practices such as walking in the city or other forms of immediate bodily encounters with the material world (Kristensen Reference Kristensen, Sami and Speed2010, 268–70, based on Connerton Reference Connerton1989 and Casey Reference Casey1987). The links with personal memory are essential here: the memorization of places and sometimes of their names, the verbalization of people's names given to places, which contributes to giving them a posterity, are all elements that join the notion of communicative, but also collective, memory.

The forum, statue display, and a view from the streets

The forum, the centre of the city and the privileged place for the elites’ self-representation, has been the most explored place for studying the construction of memory by the community. The structures of Timgad's forum (4, Figures 1 and 2) were described in detail by the first excavators (Boeswillwald et al. Reference Boeswillwald, Cagnat and Ballu1905, 1–92) and a comparative analysis of the ensemble was carried out by Pierre Gros (Reference Gros1990, 62–74), who pointed out the conformity of this building within the series of provincial, and particularly North African, fora. Francesco Trifilò (Reference Trifilò2011) subsequently suggested a new chronological and architectural sequence for the original phase of the plaza and its later developments. The detailed study of the statue bases displayed on the plaza has further highlighted the diversity of statuary types and the long period of occupation of this space, which remained essential for the self-representation of elites and emperors until the fourth century AD (Zimmer Reference Zimmer1989, 38–51), corresponding in this respect to the ‘Bildprogramm’ usually found in most of the provincial fora of the western Mediterranean (Witschel Reference Witschel and Stemmer1995, 334). However, it does not seem that this iconographic programme was the result of an upstream design associated with imperial propaganda: the locations depended above all on the available space and on the decisions made by the local authorities (Trifilò Reference Trifilò, Fenwick, Wiggins and Wythe2008, 115). The history and cultural heritage of the city were recorded in writing and images, contributing to the construction of the city's collective memory (Witschel Reference Witschel and Stemmer1995, 333). The analysis of this space is already well conducted and is part of a long tradition of studies of Roman architecture and iconography.

In order to contribute to the exploration of the experience of architecture from the point of view of memory construction, I would like to focus instead on Timgad's streets and the various perceptions attached to them – points of view of inhabitants and travellers who used them and saw the buildings along them, significant elements of a history in the network they form, and everyday reference points in the practice of the city. My approach is based on the study of Michael Hebbert (Reference Hebbert2005, 592–593), who considers that a shared space, in particular the street, may be a locus of collective memory in a double sense: on the one hand, it expresses group identity from above (top-down) through architectural order, monuments and symbols, memorial sites, civic spaces and street names; on the other, it may express the accumulation of memories from below (bottom-up) through the physical traces and associations left by the interwoven patterns of everyday life. These two perspectives can be adopted to contribute to the discussion on the experience of North African architecture.

Approaching Timgad: memory of development stages

In ancient cities, the presence of monuments was often the achievement of euergetes. These constructions required the agreement of the public authorities who decided or agreed with the sponsor on the location of these buildings. These decisions, made by notables and political leaders, were imposed on the inhabitants who encountered these buildings in their daily lives. In addition, some buildings played a special role as ‘mechanisms of transit and transition’ (MacDonald Reference MacDonald1986, 75): arches and gates were more prominent topographical markers than others, as they often defined a boundary that may have changed over time.

Under the arches: passing through space and time

Anyone approaching Timgad would arrive from one of the four roads that formed an extension of the north-south and east-west roads that ran through the early city, commonly known as the cardo and decumanus maximus (Figures 1 and 2).Footnote 3 At the very limits of the first-phase colony, but also a few hundred metres from the outskirts of the city, arches and gates spanned the streets, bearing messages delivered by inscriptions (Cassibry Reference Cassibry2018). Coming from the east or west, the traveller passed under single-bay arches, the so-called Gate of Mascula (1) and Gate of Lambaesis (13). The first arch, built around AD 158–59, was situated about 200 m from the edge of the original city and had on its façade a dedication to Antoninus Pius by the patron of the colony, which stated that the construction was financed through pecunia publica (CIL VIII, 2376; AE 1940, 19; AE 1985, 877b). The second arch was located 350 m from the western gate and was dedicated in AD 167–69, as indicated by the inscription to Antoninus Pius and his heirs Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus (CIL VIII, 2364; 2367). These gates marked the extension of the city, and their construction can only be explained by the fact that the urban settlement reached at least this location, if it did not overstep it.

The significance of the first gates crossed to enter Timgad is reinforced by the presence of others: after crossing one of these passages, the passer-by could see another gate a few hundred metres away along the same route (Figure 3). The inscriptions on these gates, located at the limits of the original city, recalled the foundation of the colony. The honorific arch located to the west (7), commonly called the ‘Arch of Trajan’ (Figure 4), must have had an inscription that was never identified with certainty. A text in the form of a tabula ansata (Figure 5) was discovered in the vicinity and may have belonged to this arch (Boeswillwald et al. Reference Boeswillwald, Cagnat and Ballu1905, 143–44): it mentioned the foundation of the colony under Trajan by the legate of the legio III Augusta, L. Munatius, dated to the year 100 (CIL VIII 2355, 17842; ILS 6841). However, other fragments of an inscription found nearby, complemented by other elements recovered from various places in the city (CIL VIII 2368, 17872; AE 1954, 153; AE 2007, 51), compose a text in honour of Septimius Severus and his family datable to the year 203 (Figure 6). This text could have found its place on the gate (Doisy Reference Doisy1953, 125–30), but these reconstructions remain hypothetical (Cassibry Reference Cassibry2018, 262). The northern gate (3), known as the Gate of Cirta, presented an inscription (Figure 7) of similar form and content to that of the western gate, which can be dated to the foundation of the colony (CIL VIII, 17843; AE 1891, 132).

Figure 3. The western street with the western gate seen from afar, near the Fountain of Liberalis (photo A. Wilson, Manar al-Athar).

Figure 4. The western gate viewed from the west. Note in the left foreground the steps of the Temple of the Genius Coloniae (photo Terrae Transmarinae, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

Figure 5. Hypothetical reconstruction of Trajanic inscription CIL VIII, 2355 possibly belonging to the western gate (image N. Lamare, after drawing by Ch. Emonts in Boeswillwald et al. Reference Boeswillwald, Cagnat and Ballu1905, 143, Figure 62).

Figure 6. Severan inscription CIL VIII, 17872 possibly belonging to the western gate (Doisy Reference Doisy1953, figure 2. Scale is approximative).

Figure 7. Hypothetical reconstruction of Trajanic inscription CIL VIII, 17843 belonging to the northern gate (image N. Lamare, after Boeswillwald et al. Reference Boeswillwald, Cagnat and Ballu1905, 127, figure 57).

The positioning of the gates, some at the borders of the original city, others at the new limits of the urban extension, combined with the chronological indication provided by the mention of the ruling emperors, allows us to define them as topographical markers of the past: they marked the stage of development of the city and indicated its period. The monumental writings – instruments of memory – also contributed to the glory of the elites (Corbier Reference Corbier2006, 13–14). The arches, ideal receptacles of engraved texts, were generally inscribed on both sides: this is not the case at Timgad, where the western gate was inscribed on its outer side only, oriented at 4.5° to be aligned with the western road – a viewpoint that was favoured (Cassibry Reference Cassibry2018, 262–63). They therefore contributed to the image of the city, particularly for those who travelled there, more than for those who lived there. If the different notions of memory overlap on several criteria, the mention of the emperors and the legion rather appeals to cultural memory in its relation to history, while the mention of the city appeals to collective memory through the identification of values shared by a group, in this case the Thamugadenses. The city highlighted the collective contribution of a construction by mentioning the financing through public funds; the financing of a patron, an alumnus, or any magistrate of the city showed the attachment of a person to the group, which gave him its recognition by also paying him tribute (Corbier Reference Corbier2006, 17; see infra). Under the Severans, between AD 209 and 211, two inscribed bases were added in front of the pedestals of the western gate (Figures 8a and 8b): they recalled the dedication of statues by L. Licinius Optatianus, but also other gifts he had offered to the city for the access to the perpetual flaminate (CIL VIII, 17829; 17835). In doing so, Optatianus communicated to those entering the colony his role in maintaining relations with the imperial family and the gods. It updated, a century later, or confirmed, after the recent dedication, the links between the city and the imperial family (Cassibry Reference Cassibry2018, 264).Footnote 4 It also associated the memory of the city with the memory of the empire.

Figure 8. Inscribed bases set up in front of the western gate. A: northern pillar; B: southern pillar (photos A. Wilson, Manar al-Athar).

The arch as a memory and spatial referent: accumulating and erasing texts

The public space was indeed suited to the display of honorific monuments and statues, or certain forms of writing such as official documents. The choice of location was either symbolic or functional: it was usually a celeberrimus locus, a particularly frequented place in the city, usually the forum or its surroundings, but also another public square. More broadly, any architectural element could accommodate writing, be the support of a text, without having any direct link with it, unlike statues or monument dedications. The monument itself will then serve as a spatial reference for the location of certain types of documents in the urban space (Corbier Reference Corbier2006, 35–37). The addition of two bases and statues in front of the western gate in the Severan period has been mentioned. Let us move away from the period under consideration for a moment to point out that some milestones (Figure 9), dating from the end of the third to the end of the fourth century AD, have been discovered in the vicinity of the gate and must have been placed near it (Boeswillwald et al. Reference Boeswillwald, Cagnat and Ballu1905, 146–50).Footnote 5 The gate became such a ‘familiar landmark’ that over time it was the obvious receptacle of various inscriptions, and these added texts must have reinforced its role as a marker of the urban landscape (Cassibry Reference Cassibry2018, 264–65). The absence of any number at the end of the text inscribed on the pillars suggests that distances were calculated from the gate: almost three centuries after the foundation of the city, and when its expansion reached at least the gates built under the Antonines, not only did the gate remain the point of reference for Timgad, but it was preferred to the forum (4), which nevertheless represented the symbolic and almost topographical centre of the city (Figures 1 and 2). The monument then became a spatial referent for the display of certain documents (Corbier Reference Corbier2006, 37), which made it a receptacle of the city's memory. Other examples can be mentioned. According to a similar pattern, the septizonium of Lambaesis remained until AD 293 – several decades after its construction in AD 226 – the privileged place for the display of inscriptions related to water in the city: it probably only lost this function in the early fourth century AD, when the aqueduct ceased to supply the city, annihilating at the same time the utilitarian and symbolic aspects of the building (Janon Reference Janon1973, 242).

Figure 9. Milestones under the western gate (photo Terrae Transmarinae, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

This accumulation of texts raises questions about the intended audience for these inscriptions. This has been discussed many times for the Roman world but let us consider the situation at Timgad. The larger clusters of inscriptions have been found in highly urbanized or militarized areas such as Numidia (Woolf Reference Woolf1996, 37). The particularly high concentration of inscriptions at Lambaesis and Timgad is easily explained. Literacy was a prerequisite for advancement in military service and veterans were probably the main inhabitants of the colony in the early days. The use of epigraphy implied an understanding of the Latin language and an endorsement of the epigraphic practice by the inscribers. These were the upper categories of society, which is confirmed, conversely, by the absence of inscriptions on almost all the stelae dedicated to Saturn found at Timgad, a cult generally associated with the less Romanized groups of the population (Fentress Reference Fentress1981, 400). The level of literacy of the population was limited to a phonetic deciphering of the texts, facilitated by the use of capital letters on the inscriptions, but which did not necessarily imply an understanding of cursive writing. The understanding of inscribed texts was also based on the repetition of formulas, sometimes abbreviated, which once memorized were more easily understood on other similar texts (Corbier Reference Corbier2006, 83–89).

Texts were accumulated but not necessarily preserved. A number of stones may have been removed or replaced entirely when they were independent of the architecture without us being able to identify them. Even when the inscriptions remained in place, a practice well known in the Roman world – the damnatio memoriae – consisted in erasing the names of persons, often emperors, who had been subject to memorial sanctions by the Senate. The names of the persons in question could be erased from the monuments or lists on which they appeared; in the case of stone inscriptions this was done by hammering. The paradox of these sanctions by erasure of the stone is that the removal itself remained visible. The proposed reasons are the practicality and economy of the cost of marble, but also the deliberate desire to preserve the memory of the traitor (Östenberg Reference Östenberg, Petrovic, Petrovic and Thomas2019, 330–31). Furthermore, the inscriptions were not only the materialized result of a historical process, but also active participants in their contemporary public space. Erasures also had meaning (Östenberg Reference Östenberg, Petrovic, Petrovic and Thomas2019, 332–33). The erasure, more than a layer removed, in stone and in memory, can be seen as a layer added to the memory of the city and to the collective memory that indirectly preserved the trace of a name. Sabine Lefebvre (Reference Lefebvre, Benoist and Daguet-Gagey2007, 209–12) explains the conservation of the two hammered bases (Figures 8a and 8b) and the Severan inscription (Figure 7) associated with the western gate, by a desire to show the hazards of power and the punishments incurred by those who transgressed the established order. The hammering of the name did not prevent it from being identified thanks to several clues but had a pedagogical value: it served as a ‘book of the history of Rome in the city’.

The gate, the arch, celeberrimi loci par excellence, defined chronological and topographical milestones of the city. They became the site for the accumulation of texts and decor, as a metaphor for gathered recollection. These constructions invoked a controlled memory, making the city a ‘memory theatre’ (Alcock Reference Alcock2002, 54, note 29). But the city of transformed monuments, sometimes destroyed, erased and yet still materialized, also allows us to study it ‘as a palimpsest’ (Fowden et al. Reference Fowden, Çağaptay, Zychowicz-Coghill and Blanke2022).

Entering Timgad: the orthogonal street grid and the memory of the foundation

Public monuments were not the only material elements that could engage the memory of inhabitants or passers-by. To pursue the literary metaphor of the palimpsest, in the same way that a text must be read between the lines, the city can be read between the buildings. In this sense, the street and its corollary, the urban grid, in its regularity or irregularity, is a structure in negative which itself carries meaning. This is what Hebbert (Reference Hebbert2005, 587) mentions about the work of Aldo Rossi (Reference Rossi1984, 99), who sought urban memory not in the monuments but in the void left between them. He argued that the street plan of the city was a ‘primary element, the equal of a monument like a temple or a fortress’. His central argument, that research on the plan of a city can reveal its structure (the soul of the city), is based on the work of Halbwachs. Developing these considerations, he argued that ‘the city itself is the collective memory of its peoples, and like memory it is associated with objects and places. The city is the locus of collective memory’ (Rossi Reference Rossi1984, 130).

Memory enclosed: preserving the grid

The question of the city's plan immediately arouses particular interest among specialists. Timgad is in this respect a textbook case as well as an exception (Le Bohec Reference Le Bohec, Piso and Varga2014). Let us take the path followed by a passer-by as he approached and entered the town. From the west, the area best known archaeologically, the structuring axis was the great thoroughfare that passed under the Gate of Lambaesis and joined the western gate. This sector must have been densely built, as shown by the remains that can be seen on satellite images (Figure 2), which are more precise than the plans published so far. To the north, an orthogonal network of a few streets developed but in a limited way: it perhaps continued under the northern episcopal complex, built at least a century later, which obliterated it, but stopped in any case towards the east at the edge of the Temple of the Genius Coloniae (8). To the south, in contrast, there is a rather irregular curved street system that led to the baths and the Capitolium (11), probably set among shops and workshops. The plots of land delimited by these streets were of unequal size and included both public monuments and private constructions, houses, or commercial units. The other sectors in the immediate vicinity of the original grid are poorly known, but a few words can be said about the southern area. There were some main paved streets, which did not cross at right angles and were even curved in some places, in the same way as in the west. Traffic also flowed through some sort of alleyways, such as those between the shops to the south of the Capitolium.

The wall that protected the city since its foundation was destroyed at the latest in the Severan period, as several constructions indicate (Lassus Reference Lassus and Chevallier1966). The city could have opened up to its suburbs, an area which was already occupied at the end of the second century and was still being developed. It would have been possible to extend, or at least to make the east-west secondary streets open out towards the western suburb, in particular in front of the Capitolium that was completed at the same time (AE 1980, 956; AE 2013, 2143), or to the rear of the Market of Sertius (10) to join the streets that extended to the west of it. This was not the case. Instead, once the wall was destroyed, the plots were rebuilt and occupied by shops to the west and by two domus to the south-west (Lassus Reference Lassus and Chevallier1966, 1223). To the north, a row of shops was also built, while the Small North-East Baths were settled at the corner of the ancient plan, on the site of the walls (Figure 2).

The image of the ancient city thus remained that of a city that was certainly not fortified but ‘closed in on itself’ (Lassus Reference Lassus and Chevallier1966, 1223), whose access remained limited to the gates that had originally been built. In the western part of the early city, a series of shops can be traced, all preceded by a portico that extended on either side of the western gate. The latter remained the necessary passage for anyone wishing to access the centre of the city, especially the forum, both pedestrians and vehicles. The same applies to the south-west, the only well-preserved part, where the north-south road that led to the Great South Baths had been left free, now framed by two rich domus. To the north of the city, this same road constituted one of the complementary entrances to the northern gate, as originally. The eastern area is too poorly preserved to distinguish possible accesses, but it can be noted in any case that the eastern gate (2) remained an open access.

When one of these gates was crossed, one entered the early centre of the city. The archway proper suggested ‘the presence beyond of a place different from that before it, of an experience in contrast to that of the present’ (MacDonald Reference MacDonald1986, 75). A very different landscape was opened up to the passer-by, consisting of small insulae which, at intervals of about 20 m, were separated from straight streets which formed a regular visual landscape (Figure 10). The distinction between the orthogonal plan of the original city and the network of streets in the surrounding areas should be felt and should even create a different atmosphere. The existence of urban centres in western Europe, often of medieval origin, offers tourists and passers-by a very different landscape from the later extensions, in a reverse situation as far as the built-up area is concerned, a centre of small intertwined streets opposed to developments with more regular streets. One cannot fail to notice this when visiting Dubrovnik, Avignon or Carcassonne.

Figure 10. The north-south street seen from the northern gate (photo Terrae Transmarinae, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0).

Was there a desire to maintain this separation between the initial settlement and the suburbs, as if there had been two categories of inhabitants (Lassus Reference Lassus and Chevallier1966, 1124)? This brings to mind our very contemporary notion of ‘historical centre’. Was Sertius’ choice to locate his domus (6) so close to the ancient centre (Figure 1) for reasons of land availability not also a matter of prestige? Beyond these social reasons for the gathering of elites (Dufton Reference Dufton2019), but also practical considerations such as proximity to the centre, available space or financial interest, one may wonder whether the oldness of the city, identified by its plan and its boundary, did not play a role: the domus is moreover inserted in the boundary of the plan by preserving its orthogonality while pushing back its external edge, as if to settle in the old centre but in reality, on a new site (Figure 2). While it is not clear whether the early city had a ‘historical’ character, it can be noted that the density of the built environment of an ancient centre was perceived in antiquity, as shown by Apuleius’ remark about an unspecified place in his novel: ‘the crowded houses of the natives left no room for the new guest’ (Metamorphoses, 1.10.6).

The maintenance of the grid plan alone is no proof of the particular interest that could be taken in it as an essential structure in the history of the city: the streets paved with heavy slabs and the presence of buildings essential to the life of the city made a major transformation of this road network impossible, and probably unnecessary. The reappropriation of the site by the inhabitants over time is attested by the phenomenon of encroachments on the street, sometimes by the assembling of two blocks to create a larger domus (Figure 1). But the preservation of this boundary between inside and outside, between the old and the new, indicates that this space was recognized as unique and that it was preserved by the community. The ‘persistence of the plan’ is the fundamental principle on which the city rests (Rossi Reference Rossi1984, 51): it is constitutive of the urban fact and its capacity to survive amid a set of transformations and is an indicator of the resilience of an urban form (Salat et al. Reference Salat, Labbé and Nowacki2011, 112).

Memory reloaded: Trajan, sunlight, and the city's orientation

Beyond the orthogonal aspect, the very orientation of the original plan of the settlement may have played a role in the memory of its foundation. Walther Barthel (Reference Barthel1911, 110–11) argued that the slight deviation of the plan from the cardinal points could not be explained by terrestrial considerations alone. The direction of the decumanus was in fact to align with the sunrise on September 18, the dies natalis of the emperor Trajan and indeed of the Colonia Marciana Ulpia Traiana Thamugadi. The calculations he made can be confirmed with greater precision by simulation software. It appears that, with an uncertainty of half a degree, the decumanus was in fact oriented towards sunrise on the date of the emperor's birthday.Footnote 6 Thus, the sunrays hit perfectly the part of the street nearest to the eastern gate, as on the day of the foundation, as well as to some extent the rest of the street, despite the slight shift of its axis (Sparavigna Reference Sparavigna2019). Considering the small orientation divergence with which the sun rose, it is possible that this alignment was almost respected in the days following, but above all preceding, the anniversary date. The appropriate moment of observation was perceptible and therefore predictable.

Although there are no written sources concerning Timgad directly, Barthel recalled the existence of city anniversaries, especially in North Africa. In an ancient city of unknown name, located at Henchir el-Dekir in present-day Tunisia, near Simitthus on the plain of the ancient river Bagrada, an inscription mentions the construction of a Curia Iovis, which can be dated to AD 185 by the mention of the consuls. The date is close to the December kalendae, incomplete in the inscription, corresponding to the natale civitatis (CIL VIII, 14683; ILS 6824; ILTun 1262; AE 1890, 156; AE 1955, 126; AE 2014, 1466). Another city, near Carthage, was founded on July 15 according to the Fasti Vindobonenses. Other examples are found in Italy, in Placentia, Beneventum and Brundisium (Barthel Reference Barthel1911, 111); let us add the day of the foundation of Rome, preserved for centuries, as the best example of all. The memory of the birthday of a city could thus be preserved and, sometimes, recalled by inscriptions. On another administrative scale, we know that the date of the creation of provinces could be used as a calendar reference, especially in North Africa.

Was the event celebrated at Timgad? It is impossible to say. The lighting of the road, in any case, was visible to all. Moreover, even if the date was not the subject of an official ceremony, it could not be avoided since nature itself was doing its work and repeated it annually. The alignment of the sunrays only occurred on the decumanus and not on the other streets joining the city from the east and west, which had a very different orientation (Figures 1 and 2). The original grid was the theatre in which the foundation of the city was re-enacted every year, thus constituting a dynamic rather than a static element of memory. The event also recalled the role of the emperor Trajan as the founder of the colony. The memory of the foundation was not only inscribed in the space of the plan but also in the time of it, which recalled its age in a cyclical way, reactivating the inhabitants’ feeling of belonging to both the civic community and to the empire through the tutelary personality of the emperor.

Crossing Timgad: structural elements and individual memory

The first two aspects I have discussed would rather involve a top-down process in the sense that the urban landscape and its negative, the city plan, are monuments and structures that are partly due to an authority, not necessarily central but at least local, in the first place the elite of the cities. However, the reconfiguration of places by the inhabitants themselves, i.e. their agency in urban planning, according to a bottom-up process, should not be underestimated: the assembly of domus within blocks or the encroachment of houses or shops on the public space of the street are good examples.Footnote 7 Hebbert also points out that inhabitants always try to reinstate elements of their familiar environment in the neighbourhood. This was demonstrated by Halbwachs (Reference Halbwachs1928, 263, quoted by Hebbert Reference Hebbert2005, 584–85) in relation to the Parisian urban fabric that was reshaped around the main thoroughfares after Haussmann's works.

Let us focus, however, on the appropriation of urban space by its inhabitants, not from the material point of view of its redevelopment, but from the memorial aspect to which it appealed on a daily basis. The work of Kevin Lynch (Reference Lynch1960) has been widely used by historians, including those of antiquity, on the way in which people get their bearings in the city. His approach is based on the existence of key elements in the structuring of the city – paths, edges, districts, nodes, and landmarks – which lead to the formation of individual images of a city, each of which corresponds to a part of the collective image. I will not look for examples at Timgad for each of these categories. Three of them, however, deserve special attention.

Landmarks: naming buildings, between individuality and community

Landmarks are a structuring element of interest (Lynch Reference Lynch1960, 78–83). They are prominent elements of the cityscape and vary greatly in scale: either the element is visible from many places, or it contrasts with the surrounding structures by a variation in alignment or height. The great public monuments of the ancient city, the theatre, the Capitolium, the great baths and the gates correspond to this first criterion, while the market of Sertius (Figure 11) or the eastern market meet the second criterion by the shift of their façade from the street.

Figure 11. The Market of Sertius viewed from the street (photo A. Wilson, Manar al-Athar).

These public buildings, often visually imposing, were therefore supposed to be landmarks for traffic and wayfinding in the city. The question of house or shop addresses has already been examined, mainly on the basis of written sources (Ling Reference Ling1990; Bérenger Reference Bérenger, Royo, Hubert and Bérenger2008). The latter do not indicate that an address was used as it is practiced nowadays in western Europe, but that vici, which were often associated with the name of a temple or an important public building (Castrén Reference Castrén2000; Bérenger Reference Bérenger, Royo, Hubert and Bérenger2008, 166–67), or monuments, which bore the name of the honoured god or of the benefactor, did not aim at accuracy but offered a general indication of the sector (district, neighbourhood) in which one dwelt.

Various monuments in the city were in fact associated with a name. On arriving from the western road, one would come across the fountain of P. Iulius Liberalis (12), built in the mid-third century AD, whose inscription could be read without too much difficulty given the proximity of the building to the road (Lamare Reference Lamare, Chiarenza, Haug and Müller2020, 32–35). A little further on, the basilica vestiaria (9) had no inscription on its façade, but next to it, the market was identified with Sertius and his wife thanks to an inscribed stela (ILS 5579). This was offered by the couple with the name SERTII appearing on the first line (Figure 12), to which were added two inscribed bases (CIL VIII, 2395–96) donated by their freedmen and placed on each side of the entrance (Figure 13), which began with the names SERTIO and SERTIAE, in larger letters, and were to support their respective statues. Opposite, on the other side of the road, the temple (8) had an inscription on its façade (AE 1968, 647) that clearly indicated its dedication to the Genius Coloniae (Figure 14) and provided the names of the euergetes.Footnote 8 These names must have been used as landmarks in this part of the city: the pronunciation of these names also revived the memory (memoria) of the dedicators, as was expected of those passing by tombs (Woolf Reference Woolf1996, 25–29; Corbier Reference Corbier2006, 87).

Figure 12. Inscribed stela ILS 5579 placed on the façade of the Market of Sertius (photo A.-F. Baroni).

Figure 13. Inscribed base of the statue of Sertius CIL VIII, 2395 placed near the entrance of the market (photo A.-F. Baroni).

Figure 14. Inscribed stone of the dedication of the Temple of the Genius Coloniae, AE 1968, 647 (photo A. Wilson, Manar al-Athar).

Other buildings probably, here as elsewhere, did not need a name because they were unique or easily identifiable: the forum or the theatre, because of their imposing dimensions or their particular shape, could be identified without attaching a name to them. The later example of the Church of Constantine at Antioch on the Orontes, simply called ‘the church’ in texts probably because it was the main church of the Christian community (Saliou Reference Saliou2014), shows that a building that is unambiguous in its identification did not need an epithet. More generally, as has been shown in relation to Hellenistic cities, the absence of a place name associated with a particular citizen must be considered as a sign of the predominant character of the community over the individuals (Larguinat-Turbatte Reference Larguinat-Turbatte, Mathé, Lopez-Rabatel and Moretti2020, 166–67). Reference should be made here to the modalities of funding of public buildings. If euergetism is well known for many of them, the most imposing edifices were financed through public funds. The study conducted at Timgad has indeed revealed a reluctant attitude on the part of the elites regarding euergetic practice (Briand-Ponsart Reference Briand-Ponsart and Khanoussi2003, 196–97), while the share of the community's investment in the financing of public monuments was more important, unlike in other cities such as Thugga (Duncan-Jones Reference Duncan-Jones, Grew and Hobley1985, 31–32). In some particular cases, very wealthy notables could contribute to buildings of exceptional importance: this is the case of the Sertii who also financed the Capitolium (11) under the reign of the Severans (AE 1980, 956; AE 2013, 2143). The city theatre (5), however, was financed by the public treasury (CIL VIII, 17867), unlike other theatres in the province such as those at Madauros and Calama (Briand-Ponsart Reference Briand-Ponsart and Khanoussi2003, 191–92). The case of the public baths is in this respect quite revealing (Thébert Reference Thébert2003, 437–39). Their financing was mainly done through public funding, and the inscriptions of the early Roman period attest to this – one of them coming from the Great East Baths, dated to AD 167–68 (Tourrenc Reference Tourrenc1968, 215), the other from the Great South Baths, dated to AD 198–99 and mentioning an extension of the building (AE 1894, 44). The latter baths were also restored during the Late Antiquity (CIL VIII, 2342). Yvon Thébert underlines the specificity of these operations, not financed by public funds but by a very practical investment of the two components of the city, the popular categories offering their labour force, the ruling elite their money: the inscription celebrates this operation by dedicating it to the concordia populi et ordinis. We observe here the essentially civic character of the baths, which contributed to reviving the memory of the community within the urban space of Timgad. In any case, stones communicated a message that existed on two levels: the text itself represented a level of meaning but it also had an embedded social meaning. Monuments and texts were perceived differently by individuals, depending on their gender, ethnic origin or social category, who constructed their own experience of the urban space (Revell Reference Revell2009, 154, 179–80).

Edges and paths: streets’ structure and hierarchy

Beyond the landmarks that provided reference points for journeys, the roads themselves, and the limits they might draw within the city, played a role in identifying the urban space and defining the image of the city. To continue this analysis based on Lynch's key elements, edges are defined as limits between two spaces, which can hardly be crossed, like an enclosure (Lynch Reference Lynch1960, 62–66). At Timgad, the ancient walls, destroyed in the Severan period but which continued to form a barrier between the early city and its extension, certainly constituted an element of reference for the inhabitants and passers-by. Without prejudice to the visual symbol of the boundary between past and present mentioned above, this boundary was also a landmark in an urban landscape that no longer had a wall at that time. It was obviously associated with a path, as a street developed along the colonnade in front of the row of newly settled shops.

Paths are precisely the channels along which the observer moves, like streets or walkways, but also canals (Lynch Reference Lynch1960, 49–62). At Timgad, perhaps even more than elsewhere because of the orthogonality of the original street network, which leads to the repetition of identical streets, a system of identification would have existed. A step that was frequently taken by the pioneers of archaeology seems revealing: at Timgad, as in so many other ancient sites, is there not a street of the theatre or a street of the Capitolium? These names, which we owe to Albert Ballu and his colleagues, result from the need to identify the streets of the city which, precisely, did not have a name.

The image of the whole city could be affected if the ‘major paths lacked identity or were easily confused one for the other’ (Lynch Reference Lynch1960, 52). A visual distinction of the streets is conspicuous and has long been noted at Timgad: the main roads, traditionally named cardo and decumanus maximus, did not have a wider carriageway but were paved with blue limestone slabs harder than those of the other roads, which helped the excavators to identify them immediately (Boeswillwald et al. Reference Boeswillwald, Cagnat and Ballu1905, 345). This hierarchy of streets, which was subtly apparent from the material used, must have been reinforced by the very activity of these streets: there were probably more people passing by, especially along the west-east axis that linked Lambaesis to Mascula, and this particular activity made it prominent among the observers (Lynch Reference Lynch1960, 50).

These more important streets had a particular name: at Timgad, the term platea referred to prominent roads that were lined with colonnades (Trifilò Reference Trifilò, Keegan, Laurence and Sears2013, 173–76). These streets were traced from the foundation of the colony and epigraphy attests that the term was used when they were paved (stratam) during the second century (Figures 1 and 2). This term therefore enabled to distinguish them, but these plateae were numerous, at least three according to the groups of inscriptions that have been identified.Footnote 9 However, an inscription datable to AD 213 indicates that during various ornamental arrangements in the sanctuary of the Aqua Septimiana Felix, a new road was paved, the one that joined the entrance of the sanctuary from the Great South Baths (Figure 1) (platea a thermis usque ad introitum).Footnote 10 It seems that this road was used before, since the temples already existed. The name of this road must therefore have been in use, taking, as is generally the case, the origin and destination as indicators (Lynch Reference Lynch1960, 54).

Moving from one place to another in the city was often done by means of landmarks that punctuated a pre-established route (Ling Reference Ling1990, 210–11; Bérenger Reference Bérenger, Royo, Hubert and Bérenger2008, 172–73), along which one could additionally ask for clarification from the surroundings. One quotation taken from Apuleius’ Metamorphoses (1.21.4) is relevant, not because it refers to a site in North Africa but because its author is African. The narrator, in search of a certain Milo in the imaginary city of Hypata, in Thessaly, questions a woman he meets on his way, who gives him this indication: ‘Do you see those windows at the end there, looking out on the city, and the door on the other side with a back view of the alley nearby? There is where your friend Milo lives’. There is no address or information that would allow a newcomer to find Milo's home, but the procedure is enlightening: one asks the locals and indicates a crossroads (node) from any landmark within sight.

The route through a pre-determined path marked out by buildings is similar to the mnemonic system used by orators to remember a speech: rhetoric (Rhetorica ad Herennium, 3.28–40; Cicero, De oratore, 2.350–60; Quintilian, Institutio oratoria, 11.2) taught to imprint in the memory a series of loci which could then be ‘visited’ throughout the speech (Yates Reference Yates1966, 3). The reason speakers used this principle was that each place or monument and its spatialization in relation to each other facilitated association with an idea or even a name. In general, it can be said that in private as well as in a public space, places and the images they contained were always likely to generate a commentary or a narrative, which was attached to them in a more or less tight manner. In this sense, every place can be considered a place of memory (Baroin Reference Baroin2010, 215–20). There was therefore a nomenclature of streets to which a name could be added and which was associated with landmarks of the urban landscape. In the case of Timgad, the designation platea a thermis usque ad introitum may have been formulated by the locals themselves and, having been inscribed in the memory of the inhabitants, may have been formalized at the time of the permanent layout of the road by the authorities.

Conclusion

The notion of memory is multiple and so are its manifestations in the urban space. The city plan, as an urban skeleton, is one of the basic structures in which this memory was embodied, even beyond the specific case of Timgad. Understanding how the original street network and alignments were preserved or obliterated, intentionally or not, is one of the key aspects of the memory of, and within, the urban space. However, working on the plan is not enough. This general framework was indeed populated by monuments and inscriptions accumulated over decades and centuries – a phenomenon very specific to the Roman world, especially around the second century and particularly at Timgad: the civic community built in this way its own memory. Focusing our analysis on the lived experience highlights the strategies of the notables of the cities in constructing the collective memory and in shaping the city.

The nomenclature and naming of the buildings also give a glimpse of the way in which the inhabitants perceived and lived their city. If street names were infrequent, buildings and their epithets were able to replace them and played their role in locating people within the city. The identification of places, the personal recollection of their epithet and their daily use helped to anchor them in the collective memory. The names were those of the emperors, placed on the arches and gates of the city, and for many of them those of the local notables: on different scales, some participated in the formation of a collective memory that linked the inhabitants to the empire, others to the social or cultural memory of the group of local townspeople. The words spoken, but also the journeys made and the places frequented on a daily basis contributed to constituting but also to maintaining this memory, or these memories as diverse as the inhabitants: ‘gestures are the true archives of the city’ as Michel de Certeau suggests, in the sense that the practices of the inhabitants, in a multitude of possible combinations, remake the urban landscape every day (de Certeau et al. Reference De Certeau, Giard and Mayol1994, 201–2).

To counter Annie Ernaux's ‘overwhelming experience’ in Cergy-Pontoise, a city without a past, the architect Antoine Grumbach expressed the wish to build ‘the ruins of a city that had existed before the new one’ (de Certeau et al. Reference De Certeau, Giard and Mayol1994, 204). These remarks commit us to continue and extend the reflection on the agency of both monuments and inhabitants in the experience of ancient cities, associating the entanglement of monuments and the entanglement of memories. The monumental accumulation of ancient cities calls for such an approach, but the phenomenon of new cities in particular raises questions about the absence of past and memory.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Niccolò Mugnai for inviting me to contribute to this thematic issue. I am grateful to him and to Victoria Leitch, editor of Libyan Studies, as well as to the anonymous reviewers for their comments on my text. This article was partly written at Kiel University with funding from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) under Germany's Excellence Strategy – EXC 2150 ROOTS – 390870439.