Introduction

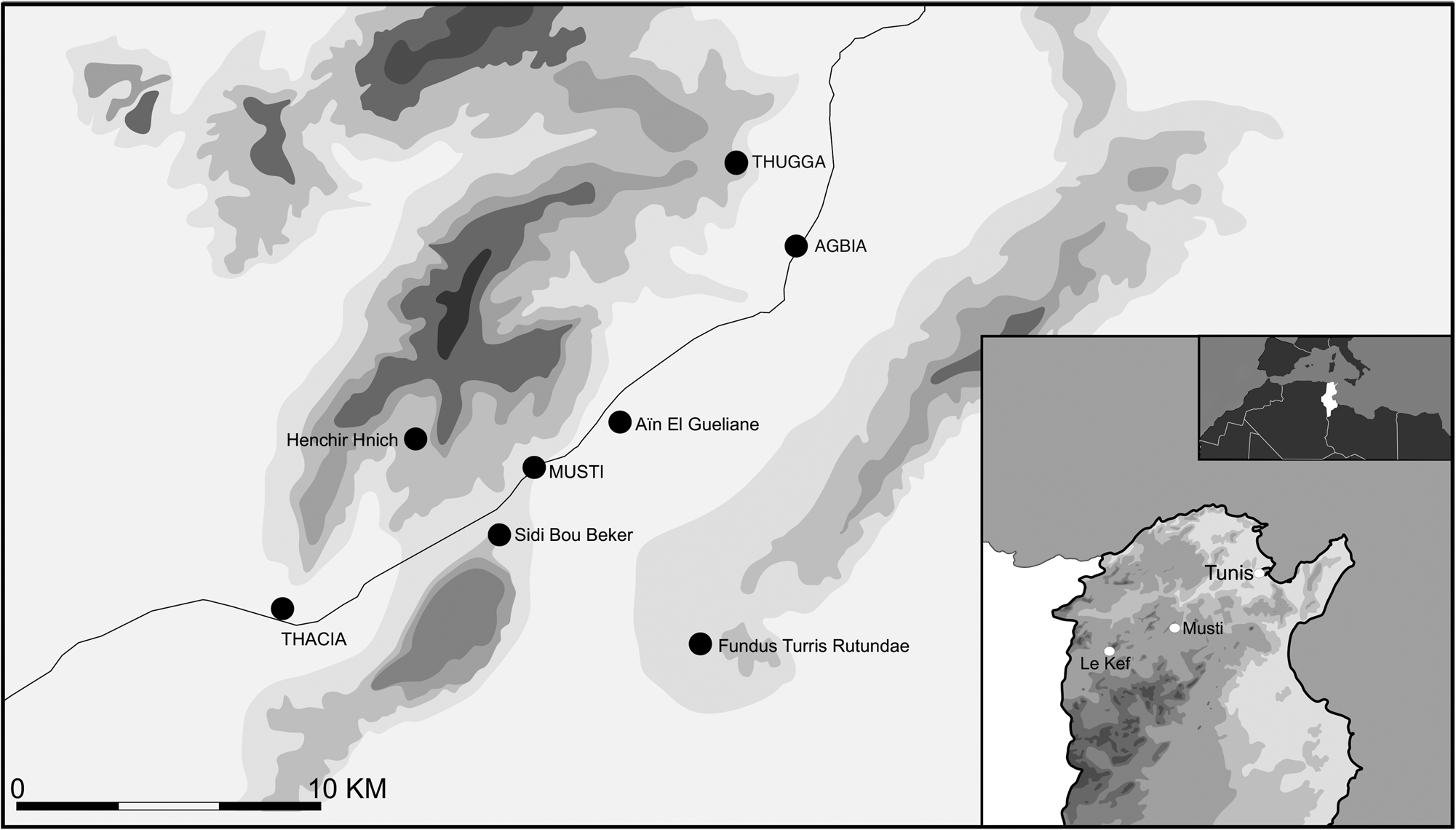

Musti/Mustis (municipium Iulium Aurelium Mustitanum)Footnote 1 was located in a highly urbanised area, 12 km from Thugga, 10 km from Uchi Maius and ca. 123 km from Carthage, along the main route leading from Carthage to Theveste.Footnote 2 The area of the entire town of Musti was estimated to cover ca. 34 ha.Footnote 3 During the early Roman Empire, Musti was surrounded by numerous private, community or imperial domains,Footnote 4 such as the imperial property in Henchir Hnich (3.5 km west of Musti), where the first copy of the lex Hadriana de agris rudibus was recently discovered,Footnote 5 or the Fundus Turris Rutundae (7 km southeast of Musti), where the coloni fun[di Tur]ris Rutundae d(omini) n(ostri) Aug(usti) were active in 235 AD.Footnote 6

Musti and the surrounding microregion included the southwestern part of the modern ‘plaine du Krib’ comprising agricultural areas and fallow lands covering approximately 100 km2 (Figure 1).Footnote 7 Nearby landforms marked clear boundaries of the farmlands surrounding Musti: Jebel Khdeit from the west, Jebel Ech-Chehid from the east and the lonely mountain range of Jebel Bou Khil, closing off the valley from the south. Only the northern limit of the town's influence was demarcated by an artificial administrative boundary of Thugga, in the vicinity of Agbia and Aunobari. The microregion of Musti lies in the fertile alluvial valley of the Oued Khalled, a tributary of the River Bagradas (Oued Majardah/Medjerda) – an important communication route and a vital agricultural area in the Tunisian Tell.Footnote 8 The heavy soils of the valley were perfect for growing crops, which were watered by annual rainfall of 500–700 mm.

Figure 1. Map of the modern ‘plaine du Krib’ with the most important ancient toponyms (drawing by M. Antos).

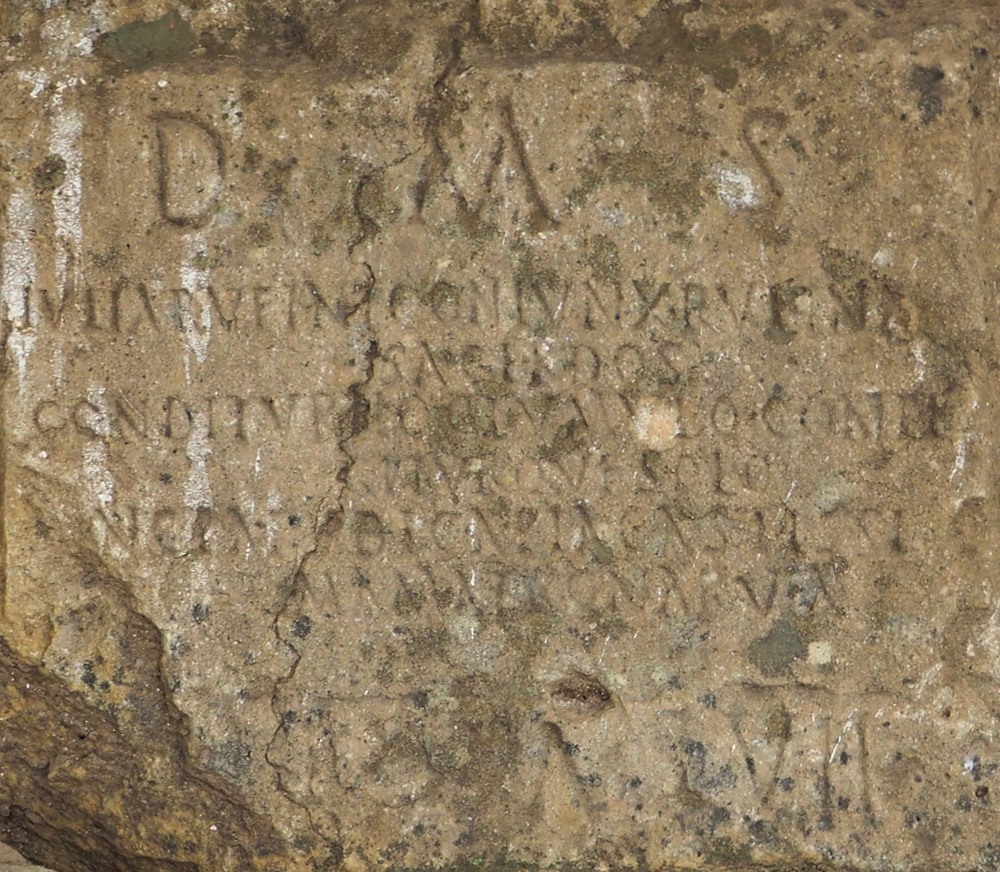

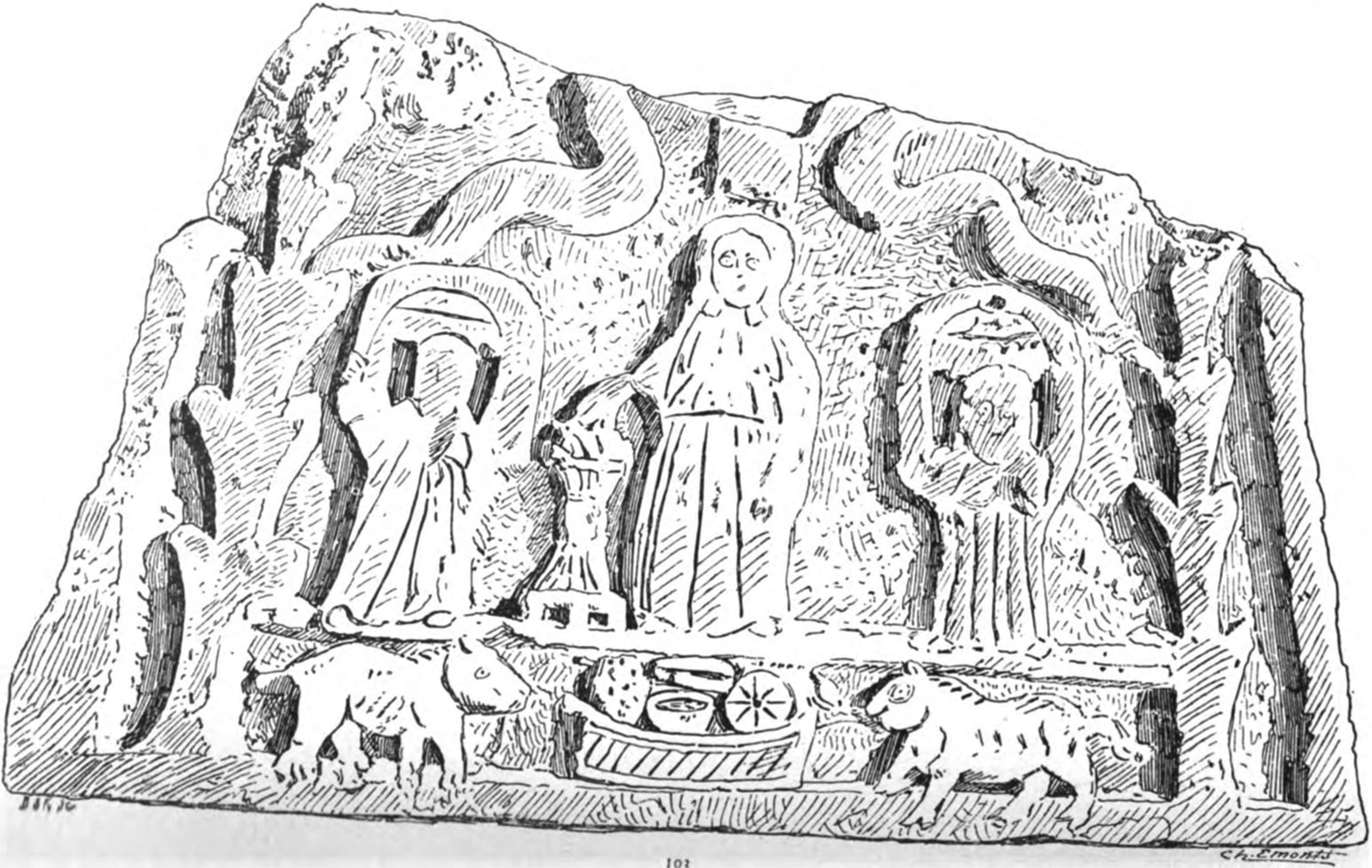

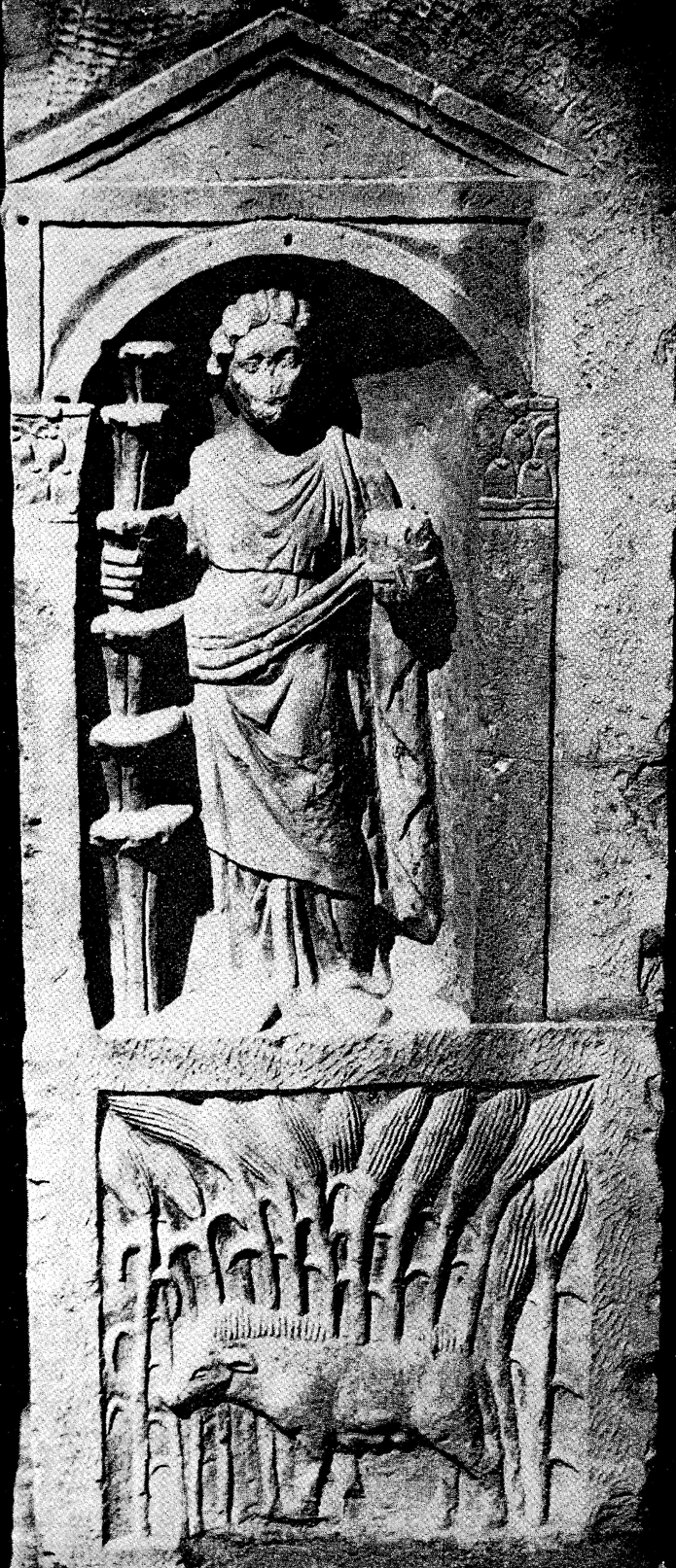

In the years 2018–2023, the Musti site and adjacent areas were investigated by the Tunisian–Polish Archaeological Mission. Three funerary monuments from Musti (no. 1) (Figure 2), Sidi Bou Beker (ca. 2 km southwest of Musti, on the southern slope of Jebel Bou Khil) (no. 2) (Figures 3–4) and Aïn El GuelianeFootnote 9 (ca. 1.5 km east of Musti) (no. 3) (Figure 5) were documented during the research, and these attracted our special attention. The monuments contain an inscription and feature unique iconography, including a female figure beside the altars, as well as images of cereals, other crops and pigs. Two of the objects are unpublished, and there was little interest in the Sidi Bou Beker monument, published in the late 1920s.Footnote 10 The exact provenance of these objects is unknown, but they certainly came from the immediate area of Musti and were documented on the nearest farms or at the site in Musti. From the same microregion, Thacia–Bordj Messaoudi (ca. 8 km west from Musti) (no. 4) (Figure 8), comes another similar anepigraphic monument, known only from a provisional drawing. Three grand stelae of the Musti microregion contain an epitaph. The fourth anepigraphic stele from Thacia shows the same relief decoration, so it can be assumed that it also has a funerary character. These four monuments are dated to the 2nd–3rd c. AD.

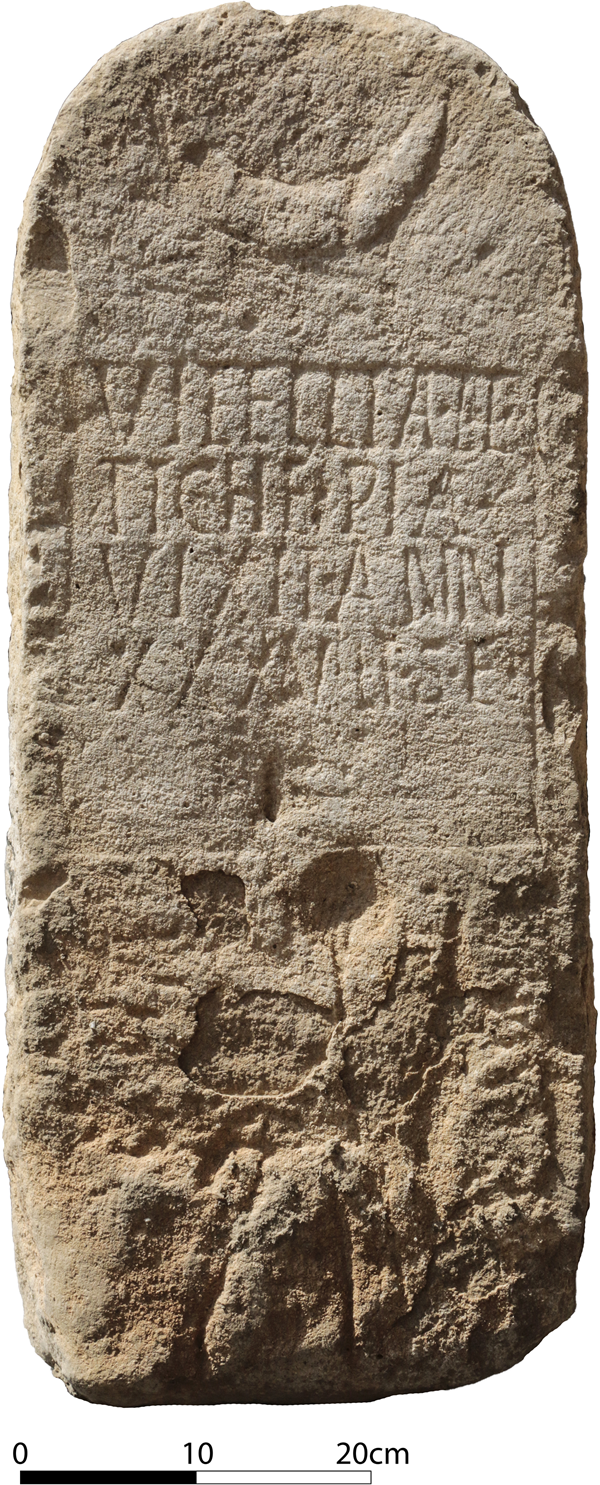

Figure 2. The stele from Musti (photo by K. Kowalewski).

Figure 3. The stele from Sidi Bou Beker (photo by T. Waliszewski).

Figure 4. The epitaph of Iulia Rufina from the Sidi Bou Beker stele (photo by T. Waliszewski).

Figure 5. The stele from Aïn el Gueliane (photo by K. Kłodziński).

Almost all objects are fragmentary, but their iconography, text, dating and stylistic parallels could be considered together. The fact that we are dealing with not one, but four similar objects means that focusing solely on epigraphic and iconographic analyses would be insufficient and would narrow the research. Therefore, finding a new methodological formula that would allow for placing the studied monuments in a broader perspective, and thus provide a multifaceted understanding of not only the local community and mortuary landscape, but also religious life and agricultural production in this microregion, turned out to be necessary. For this purpose, we used the latest eco-factual data obtained from the Musti site.

In classical archaeology, combining and analysing different types of data is nothing new. It is worth recalling M. MacKinnon's theoretical considerations, which show the great potential of interrelationships of textual, iconographical and zooarchaeological evidence in determining ‘breeds’ of animals in antiquity.Footnote 11 Each of these categories of sources is specific, and their study requires a specific methodological approach. According to M. MacKinnon: ‘Overall, ancient texts, iconographic works, and archaeological materials (bones or otherwise) often reflect different activity domains, locations, and timescales in the past, which in many cases inflicts serious challenges on interweaving their accounts into a single comprehensive narrative.’Footnote 12 However, a joint analysis of these different data seems promising: ‘Exploration of animal “breeds” in Greek and Roman antiquity represents one field for which the integration of ancient textual, iconographic, and zooarchaeological datasets shows tremendous promise.’Footnote 13 The deceased, their families and stonecutters functioned in a specific natural reality. Their activity was conditioned not only by cultural and religious elements, but also by the local economy and agricultural production and consumption.

Approaching revealed items by combining historical, epigraphic and iconographic analyses with the results of archaeobotanical and archaeozoological research will improve our understanding of the history of the Musti microregion and this part of Proconsular Africa during the early Roman Empire. Until now, such a multidisciplinary approach combining different fields has been rare;Footnote 14 historical, epigraphic and environmental studies relating to North Africa have, despite often covering similar topics, usually been done separately.Footnote 15 In this context, the characteristics of crops and livestock in the Musti area and the analysis of their importance to the inhabitants are particularly important. Seed, fruits and bones are direct evidence of the use of particular plants and animals at a particular place and time. They also bring us knowledge about these biotic elements of the past environment. But each source mentioned, because of its character, provides incomplete data. Only comparing the information contained in historical sources with the list of plant and animal taxa found in materials from archaeological sites and the artifacts described allows broader findings and a more complete assessment of the life of ancient communities.

Materials and methods

The epigraphic and anepigraphic funerary monuments with reliefs from the Musti microregion analysed in the article were presented according to a set scheme. Specifically, we provide the characteristics of the item itself (its dimensions, editions and dating, and the text of the epitaph with translation) and a historical commentary that focuses mainly on onomastics and controversial issues. Three monuments (nos 1–3) were documented between 2019 and 2023 based on direct study of the items: no. 1 – at the Musti site; no. 2 and no. 3 – on two modern farms, Sidi Bou Beker–Bordj Ouiba and Aïn El Gueliane. Meanwhile, the anepigraphic stele from Thacia–Bordj Messaoudi (no. 4) is kept in the Bardo National Museum.Footnote 16

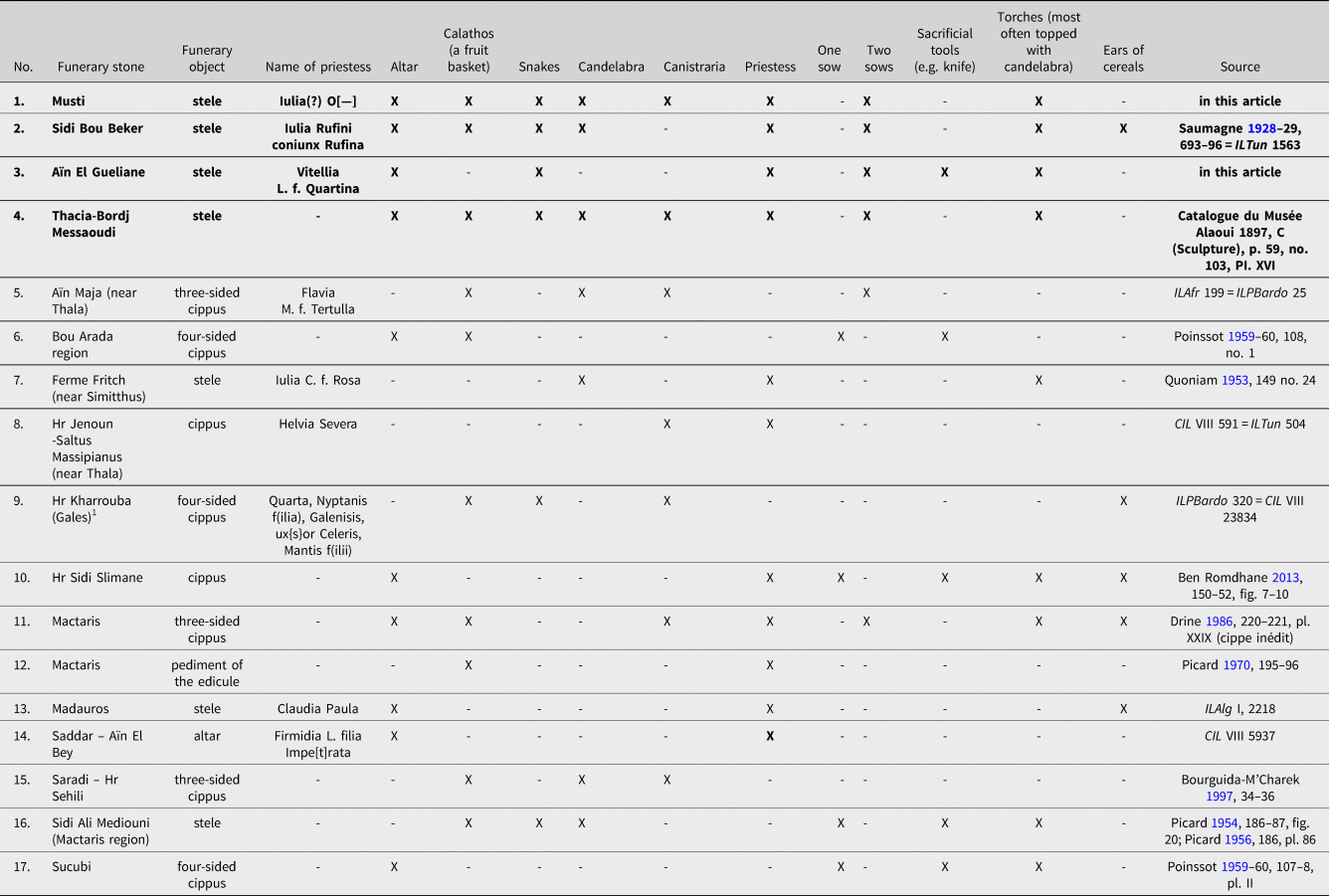

Considerations on the religious iconography of the four stelae from the Musti microregion and their comparison with other funerary stones with relief decorations from Roman Africa are based on the list of religious symbols in Table 1. Religious symbols in the funerary stones of priestesses of Ceres/the Cereres in Roman Africa. The table presents 17 tombstones with at least two symbols that are part of the canonical iconography of priestesses in this cult.Footnote 17 However, the table does not include tombstones with single decorations, such as a stele with a garland from MadaurosFootnote 18. It also excludes the funerary stele with a torch on the left from ChusiraFootnote 19 and two cippi from Ammaedara (Haïdra): the first with two columns and torches at both sides and the second whose epigraphic field was flanked by two torches.Footnote 20

Table 1. Religious symbols in the funerary stones of priestesses of Ceres/the Cereres in Roman Africa (table by K. Kłodziński).

The archaeozoological and archaeobotanical materials used in this article were obtained during the course of excavations in 2019–2022 on the site of the former Musti. Archaeobotanical samples in the form of bulk sediments were collected from each archaeological layer (context) revealed during exploration. Flotation samples (ca. 5 kg) were taken for the recovery of archaeobotanical remains from each archaeological layer (context) identified during excavation. The flotation residues (sieves 2.0, 0.5, 0.2 mm) were examined for diasporas and charcoals. Larger animal bones were collected manually during the exploration of individual contexts, and smaller fragments were collected by flotation. The chronology of individual layers was established based on the results of archaeological research (stratigraphy, ceramic finds) and C14 dating. For the purposes of this article, only those materials whose chronology was set at the 1st–3rd c. AD were selected. The archaeobotanical results presented in the article concern 14 contexts represented by 17 samples. They were associated with three trenches, where the trench T4 was located within the ancillary building near the B6 temple and the trench T7 was part of the area of the B5 temple. The trench T1 was opened in the north part of street 5, between buildings B8 and B9. The archaeozoological remains were recorded from the same contexts. Animal remains were identified in terms of taxon and anatomical elements. Standard methods were used for their analysis.Footnote 21 The data was given as NISP (Number of Identifiable Specimens).

Description of the monuments

1. Monument from Musti (Figure 2)

a) Limestone funerary monument stored at the archeological site in Musti, located at the southern wall of the so-called Temple of Ceres; discovered during excavations in 1960, Fonds Poinssot (Archives 106/94/1/10), INHA Library.

b) Dimensions of object: h. 130 cm; w. 120 cm; d. 23 cm.

c) Height of letters: l. 1: 4.5 cm; l. 2: 3 cm.

d) Dating: 2nd c. AD (the DIS MAN SACR formula).Footnote 22

e) Edition: unpublished.

f) Text:

DIS MAN SACR

ỊVḶỊA O [—]

Dis Man(ibus) sacr(um). | Ịuḷịa O[—].

g) Translation: To the Spirits of the Dead. Iulia O[—].

h) Commentary: Due to the epitaph being damaged, the reconstruction of the priestess’ gentilicium is hypothesised. Iulius/Iulia is the most popular gentilicium in all of Roman Africa.Footnote 23 Iulii are well attested not only in Musti but also in the Musti microregion, e.g., L. Iul(ius) L(uci) f(ilius) Cor(nelia) Pontius from Henchir El Oust.Footnote 24 Iulius is the most common gentilicium in the neighbouring town of Thugga (10% of the entire epigraphic evidence),Footnote 25 not to mention the nearby region.Footnote 26

2. Monument from Sidi Bou Beker (Figures 3–4)

a) Limestone funerary monument stored on a farm.

b) Dimensions of object: h. 160 cm; w. 180 cm; d. 35 cm.

c) Height of letters: funerary inscription – l. 1: 5 cm; l. 2: 2 cm; l. 3: 2 cm; l. 4: 2 cm; l. 5: 2 cm; l. 6: 2 cm; l. 7: 2 cm; l. 8: 5 cm.

d) Dating: 2nd–3rd c. AD (onomastics and the DMS formula).

e) Edition: Saumagne Reference Saumagne1928–29, 693–96; AE 1932, 16; ILTun 1563; Pikhaus Reference Pikhaus1994, 95, A132.

f) Text:

D(is) M(anibus) s(acrum). | Iulia Rufini coniunx Rufina | sacerdos, | conditur hoc tumulo conte|giturque solo, | [sa]ncta pudica pia castissi|ma matronarum | v(ixit) a(nnis) LVII.D ˑ M ˑ S

IVLIA ˑ RVFINI ˑ CONIVNX ˑ RVFINA

SACERDOS

CONDITVR HOC TVMVLO CONTE

GITVRQVE SOLO

NCTA PVDICA PIA CASTISSI

MA MATRONARVM

V ˑ A ˑ LVII

g) Translation: To the Spirits of the Dead. Iulia Rufina, wife of Rufinus, the priestess, is buried in this tumulus, and covered by the earth. She was a saint, a modest, pious and most chaste of matrons, having lived 57 years.

h) Commentary: In the editio prima the epithet pia (l. 6) was omitted.Footnote 27 The epitaph of Iulia Rufini coniunx Rufina was written in the form of an elegiac distich.Footnote 28 Iulia Rufina bears the same cognomen as her husband, which is unusual. Iulia Rufina belonged to the same family as Iulia O[—] from Musti (no. 1). Rufina is a popular female cognomen in the Principate, especially in the 2nd c. AD.Footnote 29 Four hundred and three women bearing the cognomen Rufina are known.Footnote 30 Octavia Rufina is confirmed from Thugga,Footnote 31 whereas Antonia Rufina P. f. and Iuventia Rufina are confirmed from nearby Sicca Veneria.Footnote 32 Furthermore, a senatorial woman, c(larissima) f(emina), Aemilia Tertulla Marciana Cornelia Rufina Africaniana, comes from the nearby locality of Aquae Aptuccensium (Hammam Biada).Footnote 33

3. Monument from Aïn El Gueliane (Figure 5)

a) Limestone funerary monument stored on a farm.

b) Dimensions of object: h. 56 cm; w. 83 cm; d. 14 cm.

c) Height of letters: altar – l. 1: 3.5 cm; l. 2: 3.5 cm; l. 3: 3.5 cm; l. 4: 3.5 cm; epitaph – l. 1: 2.5 cm; l. 2: 2.5 cm; l. 3: 2.5 cm. Upwards-pointing ivy leaves (hederae) are engraved in lines 1–3 of the epitaph.

d) Dating: 2nd–3rd c. AD (onomastics and the DMS formula).

e) Edition: unpublished.

f) Text:

(Vitellia Quartina?) Ma|nas | duas | i(ta) c(onsecravit). || D(is) M(anibus) s(acrum). | Vitellia L(ucii) f(ilia) Quartina | pia vixit anniṣ LXXX.MA

NAS

DVAS

IC

D ˑ M ˑ S

VITELLIA ˑ L ˑ F ˑ QVARTINA

PIA ˑ VIXIT ˑ ANNIṢ LXXX

g) Translation:Vitellia Quartina (?) consecrated in that way two (statues?) of the goddess Mana. To the Spirits of the Dead. Vitellia Quartina, pious, daughter of Lucius, lived 80 years.

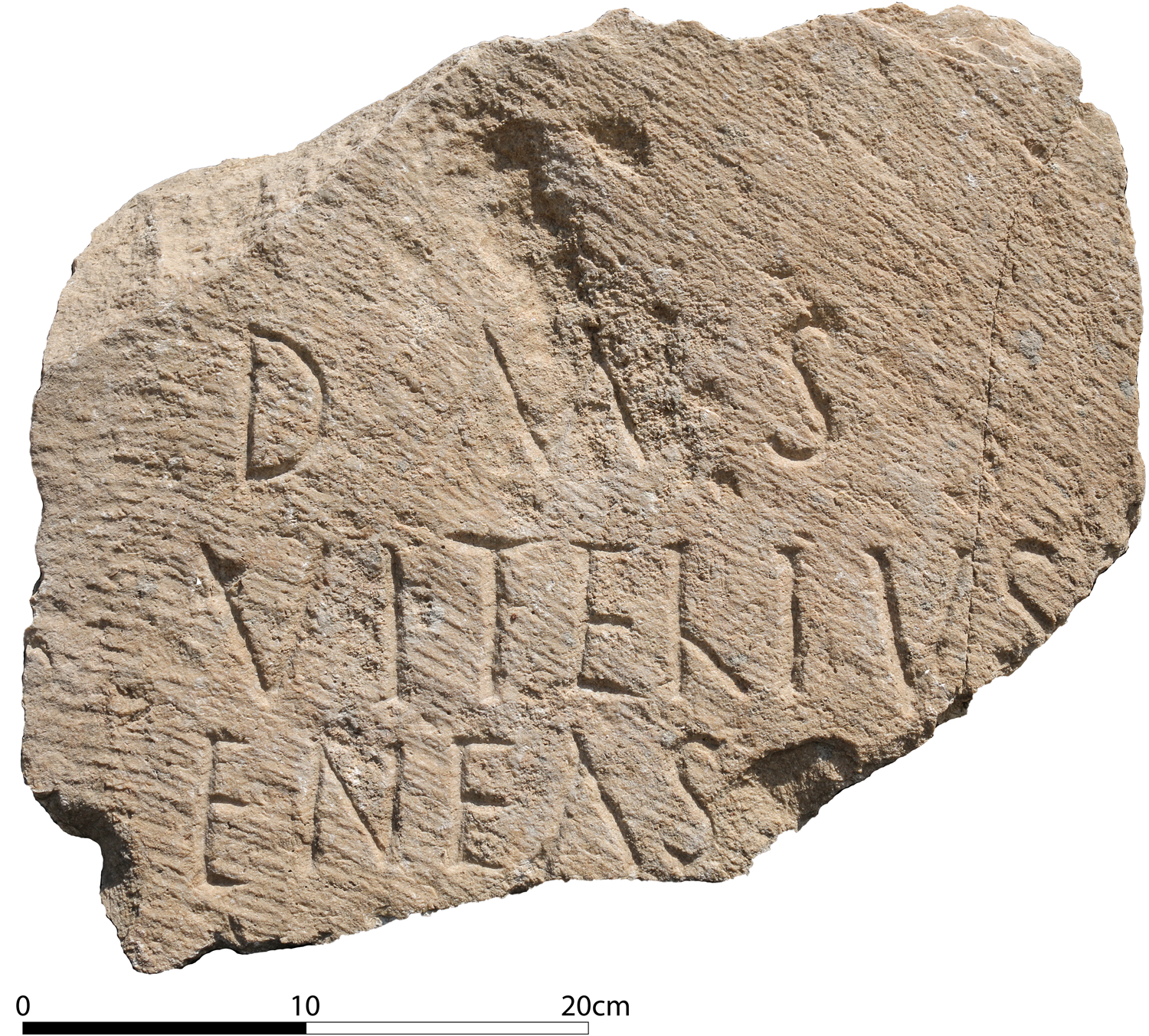

h) Commentary:The proposed interpretation of the abbreviated text carved on the altar and unattested in other Latin inscriptions is hypothetical. The accusative plural MANAS DVAS, unconfirmed by epigraphic evidence, could not relate to the spirit-gods (Manes), because the accusative plural of Manis (Manis, m.) is MANES, not MANAS. This form might be a ‘misspelled’ version of Manes, such as Dis Manes (instead of Dis Manibus) in the funerary inscription from Zmala (Numidia).Footnote 34 However, having a doubled mention of the spirit-gods, along with the invocation DMS, in the same object raises doubts. Moreover, the epitaph did not contain misspelled terms, so the term MANAS was not likely to be a stonecutter's lapsus. The personal Libyan name Mana, with the unusual localised ending Bizizi Manan, is epigraphically attested in Africa Proconsularis.Footnote 35 Explaining its potential relation to the accusative numeral DVAS and understanding the reasons for its placement on the altar are also challenging. Alternatively, the appearance of the formula on the altar, rather than in the epigraphic field of the epitaph, suggests that it may be an abbreviated votive formula, similar to Punic nasililim (‘sacrifice for god’) or ex vitulo in the votive stelae of the sanctuary of Saturn at Thignica,Footnote 36 or to an abbreviation VSLM, v(otum) s(olvit) l(ibens) a(nimo) or v(otum) s(olverunt) l(ibentes) a(nimo), altar-inscribed text on Saturn-stelae at Cuicul.Footnote 37 However, the mysterious Latin formula from the Aïn El Gueliane stele is part of a funerary monument, not a votive. There is one more option worth considering. We can assume that the subject is the deceased, Vitellia Quartina. Her epitaph must correspond to the inscription from the altar. The object, the accusative plural MANAS DVAS, depends on some verbal notion that was probably written in the abbreviated form IC (l. 4), perhaps i(ta) c(onsecravit) or i(ta) c(onsacravit). Footnote 38 The exceptional phrase may refer to the infernal Roman goddess Mana (Manae, f.), Genita Mana (or Mana Genita)Footnote 39. She received, as the goddess of childbirth, the sacrifice of a bitch (puppy). Additionally, she was connected with death and associated with the Manes and the Lares. A Genita Mana was also responsible for stillbirths. Thus, the reference to Genita Mana in the funerary inscription is not surprising, because it ‘reminds us of a fundamental application of canine liminality: the transition from life to death and the wider process of coming into being’.Footnote 40 The reference to the goddess Genita Mana was used as a metonymy for her two statues, MANAS DVAS. The metonymy, where the statue of a god or goddess is replaced by his or her name (in the accusative case), was common in Roman literature.Footnote 41 For example, the author of Historia Augusta quotes Aurelian's letter to the prefect of the city, in which the emperor emphasised: almam Cererem consecravi (I have consecrated [a statue] of fostering Ceres).Footnote 42 It seems that the action carved on the altar is the consecration of two statues, perhaps a testamentary disposition of Vitellia Quartina, but this remains a matter of speculation. Although the epitaph does not contain the title sacerdos, the iconography presented is analogous to three other objects from the Musti microregion, which allows us to assume that Vitellia Quartina was a priestess.Footnote 43 Her outfit (its upper part is damaged), consisting of a long tunic and cloak, closely resembles the priestly costume worn by Iulia Rufina, as seen on the Sidi Bou Beker stele. Moreover, Quartina died at the age of 80, which is in accordance with the image of a lifelong priesthood of Ceres/the Cereres in Roman Africa. T. Nuorluoto counted 24 women with the Latin cognomen Quartina.Footnote 44 From the mid-1st century AD female cognomina with the suffixes -īna became increasingly common.Footnote 45 The following are known from Roman Africa: Caecilia (?) f. Quartina,Footnote 46 Ulpia Quartina,Footnote 47 C[ae]sia Quartina,Footnote 48 Alfidia L. filia Quartina,Footnote 49 Quartina Luci(i) filia.Footnote 50The Latin gentilicium Vitellius is not so common in Africa Proconsularis.Footnote 51 Vitellii lived in ThuggaFootnote 52 (including the equestrian A. Vitellius Felix Honoratus, who was active in the mid-3rd century).Footnote 53 From Aïn el Ksar (2 km from Thugga) comes an inscription dedicated to Alexander Severus, his mother and his wife, whose dedicator was A. Vitellius Privatus.Footnote 54 Vitellii are also attested in Musti. In August–September 2019, a team of epigraphers inventoried over 140 Latin inscriptions. Among them were two unpublished stelae made of regional limestone that were stored in a cistern (lapidarium) within the Byzantine citadel, making their exact provenance unknown. However, they do come from the site of Musti. The first one (Inventory no. 2) is fragmentary, with damage on the right and lower parts (Figure 6). The letters are not regular, carved in rustic capitals (L in the form of lambda). The invocation DMS and onomastics (lack of praenomen) allow us to date the inscription to the end of the 2nd and the beginning of the 3rd c. AD. The present dimensions of the object are: full height, 31 cm; width, 39 cm; depth, 20 cm. The height of the letters is 4.5–5 cm.

D(is) M(anibus) s(acrum). | Vitel(l)ius | Eneas [—].

‘To the Spirits of the Dead. Vitel(l)ius Eneas [—].’

The second epitaph (Inventory no. 86) was carved on a stele with a rounded top, made of regional limestone (Figure 7). The letters are regular, carved in rustic capitals. Triangular interpuncts are carved into all four lines. The crescent of the moon and the lack of invocation DMS allow us to date the inscription to the first half of the 1st century AD. The present dimensions of the object are: full height, 84 cm; width, 32 cm; depth, 22 cm. The height of the letters is 4–4.5 cm.

The crescent of the moon

Vitellia L(ucii) l(iberta) | Tiche pia | vixit ann(is) | XXXV.

H(ic) s(ita) e(st).

‘Vitellia Tiche, pious, freedwoman of Lucius, lived 35 years. She lies here.’

The Greek cognomen Tyche (Tiche)Footnote 55 is popular in Roman Africa, particularly among slaves and freedwomen from Carthage.Footnote 56 The Greek cognomen Aeneas (Eneas), by contrast, is unattested in Roman Africa and is very rare, also indicating slaves and freedmen.Footnote 57 Three new members of the gens Vitellia – Vitellia Quartina, freeborn woman and priestess of Ceres; Vitel(l)ius Eneas; and Vitellia Tiche, freedwoman of Lucius, who lived a few generations earlier – belonged to the same family and originated from Musti.

4. Monument from Thacia–Bordj Messaoudi (Figure 8)

a) Limestone, anepigraphic and funerary (?) monument stored in the Bardo National Museum.

b) Dimensions of object: h. 100 cm; w. 173 cm.

c) Dating: 2nd–3rd c. AD (relief decoration).

d) Edition: Catalogue du Musée Alaoui, ed. Feu du Coudray La Blanchère, P. Gauckler, Paris 1897, C (Sculpture), p. 59, no. 103, PI. XVI.

Figure 6. The stele from Musti. (photo by R. Selmi).

Figure 7. The stele from Musti. (photo by F. Ogidel).

Figure 8. The stele from Thacia – Bordj Messaoudi.

Grand funerary stelae – exceptional type of the monument?

The most commented-upon monument has been that from Sidi Bou Beker,Footnote 58 which G. Picard even compared with the anepigraphic funerary aedicula from Mactar.Footnote 59 Only Cl. Poinssot, recalling an unpublished, inscribed monument from Musti, emphasised its similarity to two others from nearby locations: Sidi Bou Beker and Thacia–Bordj Messaoudi (ca. 8 km from Musti).Footnote 60 Meanwhile, L. Ladjimi-Sebaï compared the costumes of priestesses in the stele from Sidi Bou Beker with that from Thacia.Footnote 61 The most general description of the Sidi Bou Beker tombstone was given by its publisher, Ch. Saumagne: ‘La pierre affecte une forme rectangulaire à sa base […]; elle s'achève, dans sa partie supérieure, en forme de fronton triangulaire,’ although scholars differ in their categorisations of the item.Footnote 62 Cl. Poinssot categorised it as a stele,Footnote 63 but G. Picard wrote of a relief from the El Krib region or a triangular pediment of a funerary aedicula.Footnote 64 E.A. Hemelrijk classified it as a funerary cippus.Footnote 65

Although the studied group of four monuments from the Musti microregion resemble pediments of aediculae in their form, they are smaller. Pediments of aediculae are best exemplified by a monument from the Bou Arada region featuring a priestess (most likely Juno Caelestis) or a (funerary?) aedicula from Mactar.Footnote 66 The group of objects studied from the Musti microregion is a specific group. They are not cippi, altars or pediments of aediculae, but grand stelae with a massive rectangular base and triangular fronton.Footnote 67 A similar, though smaller, ‘stele anepigrafe con sommità triangolare’ (no. inv. I 319) with symbols of the Caelestis cult comes from the neighbouring town Uchi Maius.Footnote 68 The triangular fronton is an architectural reference to the Punic or Neo-Punic tradition.Footnote 69 The physical characteristics of four grand stelae in the Musti microregion stand out. They differ from the more numerous typical stelae with rounded, horizontal and triangular tops, and lack decor; they also differ from various types of cippi and other tombstones with specific physical characteristics found in neighbouring (micro)regions, including Thugga.Footnote 70 The fragmentarily preserved unpublished stele from Aïn El Gueliane, although distinguished by its form (without triangular fronton), presents the same type of relief decoration.

Defining the characteristic type of group of funerary monuments is possible in some (micro)regions of Africa Proconsularis. N. Ferchiou described a group of funerary stelae typical of the Bou Arada (Apisa Maius or Minus) region, for instance.Footnote 71 These are very high objects (up to 2 m) with specific architectural decoration resembling a complete temple facade (with columns, entablature and pediment), inside which there is a statue (or statues). Outside the Bou Arada region, e.g. in Thugga, these high temple-style stelae are very rare.Footnote 72 In the area between Althiburos and Thugga, a common category of tombstones is small aedicula (naiskos), which may have been placed in sanctuaries.Footnote 73 G. Picard described a group of specific, combined funerary arulae and cippi, named as ‘cippes-autels’, from the Mactar region.Footnote 74 In the Simitthus microregion, a category of tombstones, high ‘Menhirstele’ with a round or triangular top, typical of this area (‘eine regionale monumentale Grabmarkierungsform’), is very distinct.Footnote 75

The examined funerary stelae of the Musti microregion are distinguished not only by their architectural type, featuring a wide rectangular base (over 1.20 m) and a triangular fronton, but also by a specific and repeatable relief composition unique to this area. Consequently, we can infer the existence of a distinct stonecarving practice in this microregion, although the precise details remain unknown. It is possible that these monuments were created in local sculptors’ and stonecutters’ workshop(s), even though there are variations in paleography and the precision of iconography. However, the material (grey and white limestone) from which these monuments were made comes from local quarries and is noticeable in other epigraphic (especially funerary) monuments from Musti. While the state of preservation varies, the most intricately crafted reliefs, showcasing naturalistic images of pigs and female figures, are observed in the stelae from Sidi Bou Beker and Aïn El Gueliane. On the other hand, the iconography on the stelae from Musti and Thacia is more provisional and abstract, despite these monuments being more damaged. H. Saladin characterised the latter monument as follows: ‘Ce monument est excessivement fruste et d'un travail très barbare. Les figures, une fois dessinées et légèrement modelées par un trait gravé sur la pierre, ont été réservées le fond général qu'on a abaissé d'un centimètre et demi, à peu près. Je ne serais pas éloigné de voir dans cette oeuvre barbare, non pas un travail romain, mais un travail punique de l’époque romaine […].’Footnote 76

Priestesses of Ceres/the Cereres?

Single symbols presented in stelae from the Musti microregion are widely used in Roman African iconography. Canistrariae, fruit baskets, and torches, as well as grain and snakes, appear on funerary and votive stelae, including those dedicated to Saturn.Footnote 77 Moreover, the representation of the snake was very popular in various African cults.Footnote 78 Various deities with attributes, such as Eros, Bacchus, Hercules, Juno, Ceres/the Cereres, also appear in African funerary iconography in personified form or through symbols.Footnote 79 A woman offering incense or pouring a libation on a flaming altar is also popular in iconography of Saturn.Footnote 80 For example, in the votive stele from central Tunisia (exact provenance is unknown) dedicated to Saturn a woman stands beside an altar, her right hand over the flames, in the act of offering incense or pouring a libation.Footnote 81 However, the female figures depicted are not priestesses but rather the commissioners of the votive stelae. In the Saturn cult, male priests were featured instead of female priests.Footnote 82

The relief decoration of grand funerary stelae from the Musti microregion stands out. It does not contain personifications of deities or individual symbols, but rather a rich and coherent, almost identical iconographic composition, in the centre of which is the female figure and two sows. The identification of the grand stelae as tombstones of Ceres/the Cereres priestesses and their cult personnel seems justified for three main reasons. First, the title sacerdos of Iulia Rufina, along with her epithets sancta, pudica, pia, castissima matronarum in the inscription from Sidi Bou Beker,Footnote 83 corresponds to the exclusive epithet casta Ceres Footnote 84 or, in the plural, African castae/castissimae Cereres.Footnote 85 Secondly, the title sacerdos castissima of Helvia Severa, whose iconography on the funerary cippus features similar motifs, such as a woman sacrificing and a basket-bearing woman (canistraria).Footnote 86 Thirdly, Tertullian's account of the chastity (castitas) of the African priestesses of Ceres aligns with this identification.Footnote 87 Secondly, it can be assumed that in all four stelae the female figure standing beside the altar is a deceased person. What distinguishes them is a similar priestly outfit, a characteristic robe tied at the waist with a belt and a hood falling over the shoulders and fastened under the chin. L. Ladjimi-Sebaï noted that these specific elements characterised exclusively the costumes of the priestesses of the Cereres.Footnote 88 Thirdly, what is decisive, the four analysed stelae depict two sows, exclusively tied to Ceres in iconography.Footnote 89 The connection between women serving in the cult of Ceres and the sacrifice of sows is well attested by the funerary inscription of the Pompeii freedwoman Clodia Nigella, which was described as porcaria publica.Footnote 90 She was probably involved in breeding or selecting sowsFootnote 91 that were then sacrificed by her patron priestess of Ceres (sacerdos publica Cereris).Footnote 92

The cult of Ceres, the goddess of agriculture, has been a subject of research since the early 20th century.Footnote 93 The cult was particularly popular in Roman Africa during the Principate period,Footnote 94 undoubtedly due in some part to the exceptional fertility of African grain provincesFootnote 95 and of individual regions (e.g., the region of Bou Arada).Footnote 96 In this part of the Roman Empire, this cult was very distinct, as evidenced by the plural form of the name Cereres (Ceres–Demeter and Proserpina–Cora), with a few exceptions confirmed only in the African provinces, and by the existence of local epithets Ceres punica, Ceres maurusia Augusta, Ceres africana,Footnote 97 but also by the existence of male priests associated with the cult.Footnote 98 A particularly popular subject of research is the large group of priestesses of Ceres/the Cereres, who are referred to in the epigraphic records by various titles: sacerdos, sacerdos castissima, sacerdos/sacerda magna, sacerdos Cererum, sacerdos magna Cererum, sacerdos Cererum publica.Footnote 99 V. M. Gaspar counted 97 women associated with various cults in Roman Africa, of which as many as 54 (55.7%) served Ceres/the Cereres.Footnote 100 The numerous inscriptions include quite a large group of anepigraphic and epigraphic cippi and funerary altars with relief decoration presenting priestesses and the rich symbolism of the cult of Ceres/the Cereres. Cl. Poinssot has prepared a list of 28 monuments (not only funerary) with iconography connected to the cult of the Cereres.Footnote 101 By gathering and analysing various religious symbols presented on 17 tombstones (mainly cippi) with relief decorations of Ceres/the Cereres priestesses from Roman Africa, we will be able to capture the specificity of the unique grand stelae from the Musti microregion.

The objects studied are not the only sources confirming the importance of the Ceres cult in the Musti microregion. We know that the Cerealicii college also operated in Musti,Footnote 102 which is extremely rare in Roman Africa.Footnote 103 On the occasion of the dedication of the Arch of Commodus in Musti, C(aius) Orfius L(ucii) f(ilius) Cor(nelia) Luciscus funded scenic games (ludi scaenici) and organised a banquet for the curia and college of Cerealicii (epulum curiis et Caerealicis). Moreover, in Musti, under Trajan, there was a temple of the Cereres (templum Cererum), and, under Severus Alexander, a statue of Ceres Augusta was dedicated.Footnote 104 In Musti, there were also male priests associated with the cult of the Cereres who, though rarely confirmed in the epigraphic records,Footnote 105 bore the title sacerdos Cerealium or patronus Cerealium.Footnote 106

Religious symbols in the funerary stones of priestesses of Ceres/the Cereres in Roman Africa

Symbols of the cult of Ceres are attested not only in the funerary iconography of priestesses of Cereres, but also on African tombstones depicting personifications of the Cereres and their attributes, such as the cippi of Theveste and Abthugni. In the case of these two monuments the deceased were quite young (Aelia Leporina 39, Domitia L(ucii) fil(ia) Concessa 43, S[—]a L(ucii) fil(ia) Fortunata 18 years), so they do not fit the age profile of elderly priestesses, and none of them was described as sacerdos. Iconographic references to the Cereres (in the case of the Aelia Leporina tombstone, also to Juno) probably symbolised loyalty and attachment of the deceased to these goddesses and placing themselves under their protection.Footnote 107 The four-sided funerary monument from Theveste, the front of which contains the funerary inscription of Aelia Leporina, presents the specificity of the iconography of the Cereres cult in Roman Africa.Footnote 108 Each of the remaining three sides of the stele resembles a temple façade with a triangular pediment and a niche between two pilasters with Corinthian capitals. Each of the three niches contains a personification of the goddess with attributes, which together create a ‘triple representation divine’.Footnote 109 According to M. Leglay, the back of the stele presents the image of Juno, whereas the sides present two goddesses: Ceres–Demeter and Proserpina–Cora.Footnote 110 In the lower part, under the niches with the goddesses Cereres, who are touching a torch with their right hand and holding a small box (cista mystica or capsa) or an incense box (acerra) in their left hand, there are two iconographic compositions. On the left side of the stele (Cora, Figure 9), a pregnant sow is walking rightwards, and in the background there are ears of wheat or barley,Footnote 111 flanked on each side by a basket containing fruit and flowers. In the lower right of the stele (Demeter, Figure 10), a sow, most likely also pregnant, is walking leftwards, and behind her there is a field with plump ears of what is probably wheat.

Figure 9. Left side of the Theveste stele (source: Leglay Reference Leglay1956, 40).

Figure 10. Right side of the Theveste stele (source: Leglay Reference Leglay1956, 38).

However, the richest symbolism of the cult of Ceres can be observed in the iconography of the priestesses’ tombstones. Of the various symbols of the cult of Ceres, the torch, the basket of fruit, snakes, sacrificial tools, canistrariae and ears of cereals, it is the sow that occupies the foreground.Footnote 112 A constant and major compositional element of relief decoration of the stelae studied is a pair of sows placed either side of the altar, flanked to the left and right by torches. The only similar representation of these symbols, a direct reference to the Cereres, is found in the decoration of a monument from Turratensium in the Theveste region (Figure 11).Footnote 113 There, flanked by torches to the left and right, two sows are placed on either side of a basket (calathos) that is laden with fruit and covered with a snake. Moreover, this decoration accompanies a sacred inscription dated to 212–217 AD and dedicated to the Cereres and Pluto, and pro salute Caracalla and the whole divine house by the Turratenses, and not the funerary inscription of the priestess of the Cereres.Footnote 114 Two sows are also depicted on the tombstone of the priestess (sacerdos) Flavia M. fil(ia) Tertulla from Aïn Maja (near Thala).Footnote 115 However, it is important to note that this tombstone is a three-sided cippus. The two lateral sides of the cippus depict one sow each, along with a canistraria carrying a basket on her head. A similar iconography, featuring one canistraria and one sow on the two lateral sides, can be observed on an anepigraphic, also three-sided, unpublished cippus from Mactar.Footnote 116 Another inscription from Roman Africa also indicates a direct connection between sows and the cult of the Cereres: a sow wearing a laurel wreath and embellished with a ritual dorsal decoration, as ex voto offering to the Cereres, is presented in bas-relief with a fragmentary votive inscription from Utica (Figure 12).Footnote 117

Figure 11. The sacred inscription from Turratensium, CIL VIII 16693 = ILAlg I, 3517 (source: https://db.edcs.eu/epigr/bilder.php?s_language=en&bild=$CIL_08_16693.jpg, DOA – 13.11.2023).

Figure 12. The fragmentary votive inscription from Utica, ILPBardo 435 = CIL VIII 25378 (photo by K. Kłodziński, the Bardo National Museum).

The sacrifice of a sow to the goddess Ceres (or Demeter in the Greek cult) was a ritual practice often described by ancient authors and presented in art.Footnote 118 This animal served three main functions: as a sacrifice offered cyclically by cult officials; as a cleansing offering that was an element of funeral rituals; and as an ex voto. At the end of January, during the feriae sementivae, farmers made offerings to Ceres and Tellus – the two frugum matres – of the spelt and the entrails of a pregnant sow (farre suo gravidae visceribusque suis).Footnote 119 While describing the games of Ceres (Cereris ludi), for April 12, Ovid wrote that, in spring, a lazy sow (ignavam sacrificate suem) was sacrificed to the goddess Ceres.Footnote 120 Furthermore, on January 9, the poet noted: ‘The first to joy in blood of greedy sow was Ceres, who avenged her crops by the just slaughter of the guilty beast; for she learned that in early spring the grain, milky with sweet juices, had been rooted up by the snout of bristly swine.’Footnote 121 Cato wrote of a young sow (porca praecidanea, porca femina) that was to be sacrificed to the goddess Ceres not in spring but in summer; this was to precede the harvesting of spelt, wheat, barley, beans and rape seeds.Footnote 122 Cicero, Varro, Aulus Gellius and Festus also wrote about an obligatory funeral ritual, a cleansing sacrifice of a porca praecidanea or porca praesentanea, a female pig sacrificed to the goddesses Ceres and Tellus.Footnote 123 The set of four stelae is unique not only for the African provinces, but also for the entire Roman Empire. Only three funerary reliefs are known from Italy, and these represent priestesses of the goddess Ceres sacrificing a sow on an altar, or contain a representation of a sow alone.Footnote 124

Most of the religious iconographic features that can be identified on the fragmentarily preserved funerary stelae from the Musti microregion are also attested in other funerary stones of Ceres/the Cereres priestesses from Roman Africa and constitute part of the cult's symbolism. Of the 17 tombstones of the priestesses of the Cereres in Roman Africa (Tab. 1), the sow is depicted in ten cases. Only in the cippus from Henchir Sidi Slimane (no. 10) is one sow with a piglet presented. This unique iconographic composition, presenting a piglet falling out of a sow, may be a reference to the sacrifice of the entrails of a pregnant sow, which Ovid wrote about.Footnote 125 Apart from two three-sided cippi from Aïn Maja (no. 5) and Mactar (no. 11), in which two sows with canistrariae (female basket-bearers) are carved on the two front-facing sides, only four stelae from the Musti microregion feature a frontal representation of two sows, one on either side of the altar, the basket, or the epitaph, slightly below the presented priestess. The sows are depicted in sacrificial imagery, and on each of the stelae (perhaps also from Aïn El Gueliane) a priestess pouring a libation on a flaming altar is carved. An altar (varying in shape) at which the priestess stands is another constant feature of the relief decoration of the stelae from the Musti microregion (nos 1–4), although this symbol is visible in as many as six other tombstones of priestesses of Ceres (nos 6, 10, 11, 13–14, 17). In most cases, the priestess stands at the altar, most often in a sacrificial gesture, but in the stele from Ferme Fritch (near Simitthus) (no. 7) the female figure has her arms crossed, and the priestess depicted in the stele from Sidi Ali Mediouni (Mactar region) (no. 16) holds her hands up: in the right there is a caduceus and in the left there is an ear of corn.

The canistrariae were an important complement to the sacrificial scene in the grand stelae from the Musti region. However, they were common in the cults of several deities, not only Ceres/the Cereres.Footnote 126 Long torches of Ceres–Demeter (associated with her search for Proserpina–Cora), often topped with candelabra, are confirmed in several items (nos 1–4, 7, 10–11, 16–17). However, only on the studied stelae are they a constant feature of the decoration, and the torches on each side lead to the basket (calathos), which is placed at the very top of the triangular fronton. (However, these symbols cannot be confirmed on the stele from Aïn El Gueliane, due to the object being damaged, no. 3, Fig. 5) A snake or two snakes – an attribute of Ceres (Demeter)Footnote 127 but also a symbol of fertility – wrapped around a basket or torches are attested in six cases, including all four from the Musti microregion (nos 1–4, 9, 16). In the case of stelae, the snakes accompanied the torches and were directed toward the basket located at the top of the triangular fronton. Sacrificial tools (instrumenta sacra) associated with the cult of Ceres, such as a set of knives or a triangular knife (secespita, culter),Footnote 128 a dish (patera), a scoop, or tweezers, are carved in several cases (nos 6, 12, 14), but they are not confirmed in stelae from the Musti microregion. In the stele from Aïn El Gueliane (no. 3, Fig. 5), a canistraria holds in her left hand a downward-pointing object with a branched end that resembles an aspergillum.Footnote 129 Interestingly, an important attribute of Ceres/the Cereres – ears of cereals – appear quite rarely in the decorations of the tombstones of priestesses of the goddess(es). They are confirmed in only five cases (nos 2, 9, 10–11, 13), but they are represented most fully as a bunch of ears of cereals in the Sidi Bou Beker stele (no. 2, figs 3–4). The ears shown are most likely to be of wheat. Furthermore, the sows featured in this stele are shown holding some plants, possibly leaves like laurel leaves, in their mouths,Footnote 130 a unique element in Roman visual culture.Footnote 131 These are certainly not the boar tusks that Ch. Saumagne wrote about.Footnote 132 Furthermore, in the Thacia–Bordj Messaoudi stele, in the lower part of the decoration, between sows, there is a large basket full of fruit, vegetables and bread, which is entirely unique for such monuments.

Such a large concentration of agrarian motifs and similar relief decoration in the funerary stelae from the Musti microregion – and especially the unique image of two sows between the altar and the priestess – cannot be a coincidence. The stelae in question, whose iconography draws fully from Greek and Roman culture, are rooted in the local context, and the stonemasters, expert sculptors, were operating in a specific and regional context with its own distinctive features.Footnote 133 However, we know nothing about the individuals involved in the creation of any of the above-mentioned stelae, including their designer(s), commissioner(s), or, finally, local stonecutter(s)–sculptor(s). Undoubtedly, the rich relief decoration of these four objects reflects the fertility and agrarian character of the Musti microregion in the times of the early Roman Empire, which is confirmed by the latest environmental research.

Environmental analysis

The rich and detailed epigraphic and iconographic sources provide a solid foundation for the suggestion that the stelae, which are the subject of the study, are significantly related to the cult of Ceres/the Cereres. They also fit perfectly into the highly agricultural character of the microregion mentioned in the historical sources. It is therefore interesting to note the environmental background obtained from the analysis of fossil plant and animal remains collected during excavations in Musti. However, it is important to note some aspects related to these studies. Despite the rich data on the Roman history of the site, there are not many archaeological, and thus environmental, results. This is because cultural layers representing the Roman period were partially removed from the town in the late-antique/medieval period and then again during excavations in the 1960s. Archaeobotanical or archaeozoological discussion is also limited because in the vicinity of Musti there are no archaeological sites where plant or animal remains have been analysed. It would be better to look at the nature of the local environment. The only sites in Tunisia that provided interesting data of this kind are located relatively far from Musti, and their chronology is not always related to the Roman period.Footnote 134 Despite such limitations, the archaeobotanical and archaeozoological results obtained so far are a very important addition to the overall picture of Musti's functioning.Footnote 135

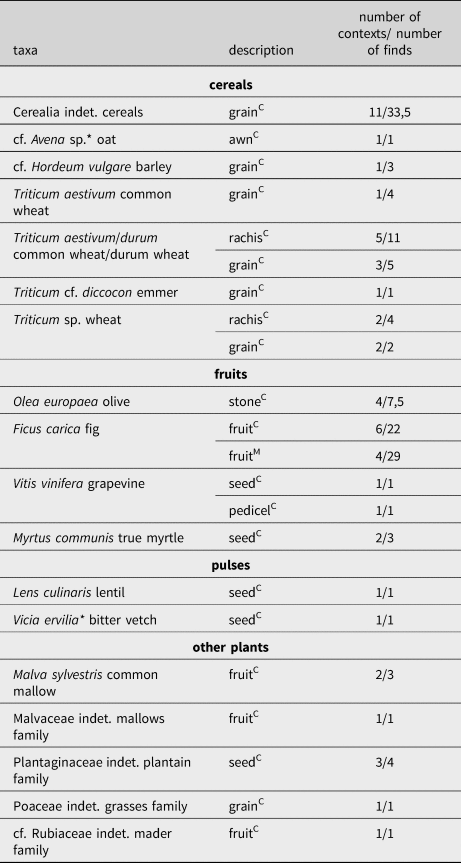

The environmental data included in the analysis are derived from archaeological strata excavated in the central part of Musti, near the Roman road traversing the city and the forum transitorium, including on buildings adjacent to the so-called Temple of Apollo and the area of the so-called Temple of Ceres. Each of 14 discovered contexts represents the typical useful layers that lie within the city's boundary. Among these, in only one case were no plant remains found. In the remaining contexts, mainly charred or mineralised seeds and fruits were recorded. A small number of finds is normal for archaeological sites in the region of North Africa. This is primarily an effect of natural conditions, largely climatic, which impede the preservation of uncharred plant remains. The list of taxa from Musti includes 18 determinations representing mainly useful plants (Table 2). The group ‘other plants’ contains plants belonging to the ruderal and segetal communities developing near the city.

Table 2. Listing of the taxa recorded in the contexts dated to the Roman period. * – cultivated plant or weed, C – charred, M – mineralised.

The material is dominated by remains of cereals, mainly wheats (Triticum aestivum/durum, T. cf. dicoccon). It is worth noting that wheat was preserved not only in the form of charred grains but also rachis. This may indicate that cereal came to Musti in the form of cleaned product (grains), but also ears, which were then processed on site. It can be assumed that the cereals used in the town came from the surrounding fields. Ears of cereals, most likely wheat, were also preserved on an unpublished architectural element from Aïn El Gueliane, perhaps presenting a hunting scene, documented during the survey in 2019 (Figure 13). This may be further proof of the presence of cereals in the microregion of Musti and the significant symbolism of this group of plants for the inhabitants. Apart from the wheat, single remains of barley (cf. Hordeum vulgare) and oats (cf. Avena sp.) were found in the archaeobotanical samples. In the latter, the wild form of oats cannot be ruled out because the determination was based on awn remains.

Figure 13. The fragmentary (upper part?) of an architectural element from Aïn el Gueliane (photo by K. Kłodziński).

The group of fruits contains remains of both cultivated plants and those collected from the wild. In terms of the number of finds, the remains of fig (Ficus carica) dominated, preserved both in charred and mineralised form. Next to them, single remains of grapevine (Vitis vinifera) preserved in the form of seeds and stalk were found. Fruits of both plants could be eaten fresh or after processing. What is surprising is the fact that the material from Musti contains few traces of olive (Olea europaea). It is possible that its remains represent fruit that were transported to the city for direct consumption and had nothing to do with the obtaining of oil. It is worth adding that the architectural fragment from Aïn El Gueliane also contains an image of a small tree (Figure 13). Unfortunately, its state of preservation and the lack of diagnostic features do not allow us to determine precisely whether we are dealing with a fig tree, an olive tree or a palm tree.

Apart from the typical cultivated species, remains of myrtle (Myrtus communis) were also noted. This is an evergreen perennial shrub or a small tree that is widespread throughout the Mediterranean region and the Middle East.Footnote 136 Myrtle usually grows wild, but it cannot be ruled out that the remains from Musti represent cultivated ones. This is because of its aromatic properties, edible fruits, fragrant white flowers, evergreen and culinary leaves and uses in traditional medicine.Footnote 137

In the past, legumes were second only to cereals in importance for consumption.Footnote 138 Pulses, generally cultivated and easily collected, do not need any tool and ripen earlier than cereals, and most of them can be eaten before they ripen, when they are still green. However, their finds in the form of accumulation on archaeological sites are usually rare. This reflects the poorer preservation potential and underrepresentation of legumes in archaeological contexts.Footnote 139 We also face such a situation in Musti. In the material dated to the Roman period, only a single find of lentil (Lens culinaris) and one of bitter vetch (Vicia ervilia) were noted. The former is one of the first domesticated grain crops. Lentil seed is an excellent source of energy, dietary protein, fibre and micronutrients.Footnote 140 Seeds of bitter vetch have toxic properties, so may not have been intended for human consumption but used as fodder or famine food.Footnote 141

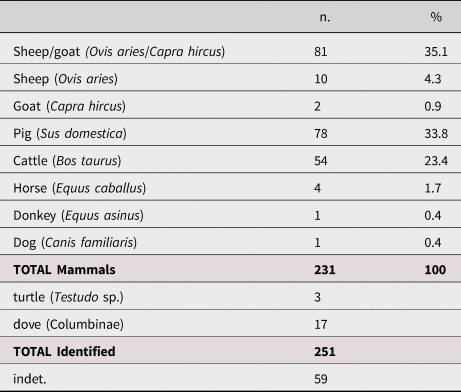

Animal remains were discovered in nine out of 14 contexts discussed in a total number of 310 fragments (Table 3). However, most contexts contained a small number of remains. Their state of preservation was relatively good. Despite the desiccation that caused the crumbling of the bones, only 19% of the bone fragments were not identified. They were typical kitchen waste with numerous bones bearing the marks of chopping, cutting and dismembering. The animal remains chiefly came from domestic animals, and no game remains were found. Additionally, in one of the contexts, the remains of a dove that probably died naturally there were found. Other remains that did not belong to livestock were from a turtle. They too were located in a single context, so they could probably have come from the plastron and carapace of a single individual turtle, cf. Testudo sp.

Table 3. Animal remains from the contexts dated to the Roman period.

Livestock from Musti was represented by four main species: sheep, goat, pig and cattle. Sheep and goats are the most characteristic animals kept in Northern Africa because of their high tolerance for poorer-quality forage and smaller amounts of water (goats, in particular, are well adapted to weaker environmental conditions). Their husbandry is relatively easy and requires few breeding procedures. Instead, these animals provide primary (meat) and secondary (milk, wool) products. The proportion of sheep to goat remains was 5:1. Similar predominance of sheep remains was also recorded at the other sites in Tunisia in the Roman period.Footnote 142 The ovicaprine remains came from young and adult animals, indicating their husbandry in the area. The presence of lamb and goat kid remains among the kitchen waste of the inhabitants of Musti suggests a demand for delicate meat and well-developed breeding with a surplus of young individuals.

On the other hand, the pig was an animal rarely kept in significant numbers in Tunisia, especially in the pre-Roman (Phoenician) contexts. Their greater importance is linked to the influence of the Roman Empire.Footnote 143 According to some authors, pork was an important part of the Roman diet.Footnote 144 However, in Northern Africa, where the temperatures reach 40 degrees, pigs are not easy to raise, as they are susceptible to heat stress because they have few functional sweat glands. It is interesting to note that pigs also need more drinking water than other livestock. Research shows their presence in Tunisia during earlier times. In neighbouring areas, pigs were bred even in the Neolithic period in considerable numbers.Footnote 145 However, the Phoenician settlement caused pigs to be considered unclean and their breeding in this region to lose importance.Footnote 146

Pig remains recorded in Musti were abundant even compared with other bone materials from the Roman sites. Only at sites such as Carthage and Althiburos was their frequency similar to that in Musti, reaching over 30%.Footnote 147 Their share was much lower in the nearby Zama region than in Musti: less than 9%.Footnote 148 The preserved remains did not allow an analysis of animal morphology due to their fragmentation. However, by comparing them to the reference collection, it seems that they belonged to small or medium-sized individuals, but it is uncertain whether they originated from a large pig or a wild boar. The current range of the wild boar, the wild ancestor of the pig, includes, among others, the northern Mediterranean coast of Africa. Wild-boar hunting was known from Roman times in Tunisia, and it is depicted in mosaics from Carthage and Radez, among other sites.Footnote 149 Unfortunately, epigraphic or iconographic data are not helpful in determining exactly which animals could have been bred or kept in the Musti area. Authors commenting on iconography on tombstones mention a pig, sow, or wild boar.Footnote 150 G. Picard had doubts about the identification of the animal from the Sidi Ali Mediouni stele (no. 16).Footnote 151 A similar doubt applies to the remaining tombstones discussed above. The stelae from the microregion of Musti are also inconsistent in their depiction of these animals. The stelae from Musti (no. 1) (Figure 2) and Aïn el Gueliane (no. 3) (Figure 5) show animals with smooth fur and without the characteristic bristle, while the stelae from Sidi Bou Beker (no. 2) (Figure 3) and Thacia – Bordj Messaoudi (no. 4) (Figure 8) most probably show animals with the bristle. The bristle is characteristic of a wild boar and may also occur in the primitive form of a pig. According to M. MacKinnon, in the case of pigs mentioned by Roman authors, there are two types: larger, ‘smooth-skinned, great-bodied, large hips, white-bellied, long in shape, ample and round; pastured in warmer, sunnier regions’; and smaller, ‘smaller-sized; hard, dense, black bristles; similar to wild boar’.Footnote 152 It seems, therefore, that the remains from the Roman contexts at Musti could have represented both these forms, taking into consideration the archaeozoological and iconographic data. However, there is also a probability that a large ulna discovered could have belonged to a wild boar.

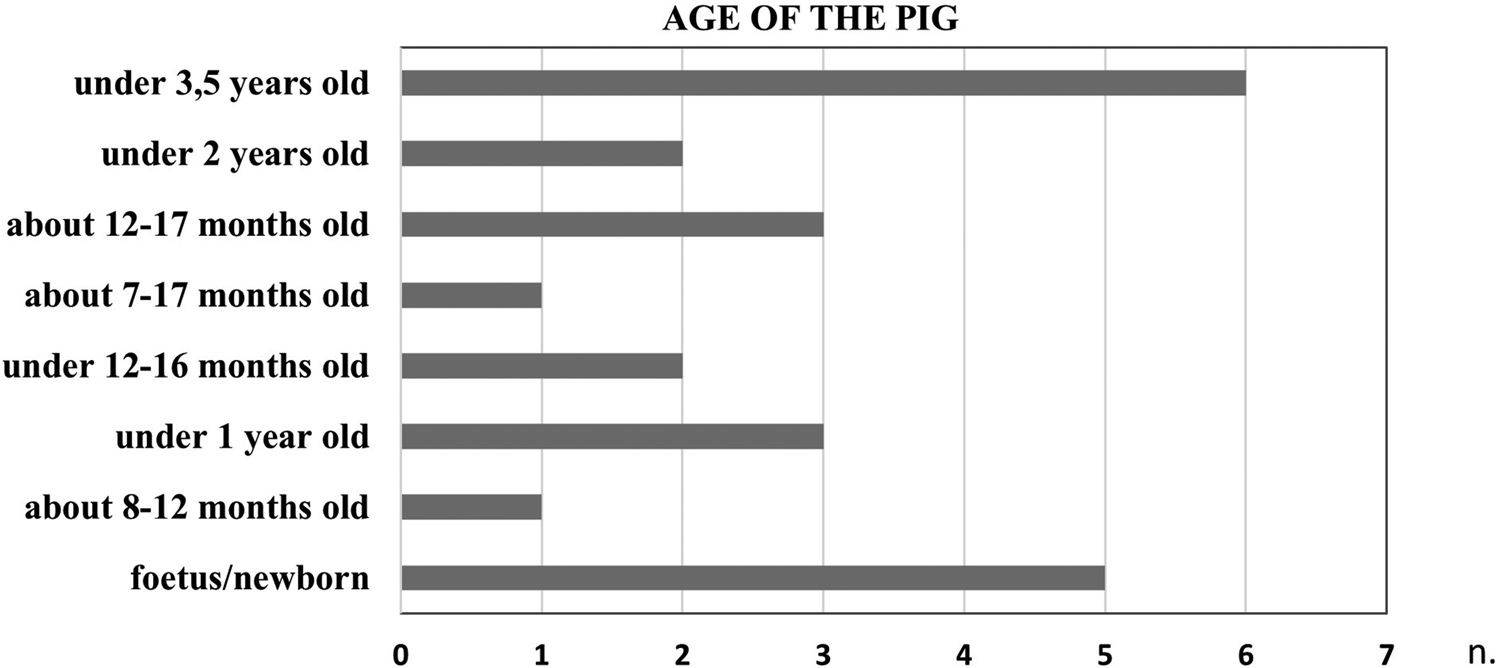

Almost a third of the bones were from young animals (Figure 14). The interpretation is similar to the case of the remains of the young ovicaprines. However, the pig is kept for only one purpose (meat) and is a very fertile animal. It can birth ten or even more piglets in an annual litter. Therefore, youngsters not needed for further breeding (especially males) can easily be destined for consumption. The meat of piglets is known for its delicacy. It is important to note the appearance of five foetal/neonatal pig bones in three contexts dated to the Roman period, one of which was confidently from a foetus. Although the high perinatal mortality may be the result of poor rearing conditions for these animals, the presence of these bones is interesting in the context of the rituals described by Ovid (Fast. I, 671–72), in which pregnant sows were sacrificed to Ceres. In addition, depictions of pregnant sows are known from the tombstones from Aïn Maja (no. 5), Hr Sidi Slimane (no. 10) and perhaps Sidi Ali Mediouni (no. 16).

Figure 14. Share of young pigs in different stages of bone and tooth development process (by U. Iwaszczuk).

Cattle husbandry requires a large amount of water. The animals also need an extended breeding period before they reach their target weight, and they usually have only one calf per litter. It also takes time before they can perform as draught animals (usually about four-year-old animals are morphologically mature and can be used for work). That is why the lower percentage of their bones is not surprising. The lesser importance of cattle is also characteristic of other Tunisian sites from the Roman period.Footnote 153 As in the case of ovicaprines, the remains of cattle came from young and adult animals. However, the calves were older than the lambs and goat kids. The bone of the most immature calf belonged to an individual between 15 and 18 months old, while the other remains came from subadult and adult animals.

The remains of transport animals (horses, donkeys) and dogs were very few, which is also typical of the other Roman sites in Tunisia.Footnote 154 The bones came from adult animals, showing that they belonged to animals used for traction or riding rather than for their meat. There were no post-consumption marks on these bones, which may be an additional confirmation of this thesis.

The archaeobotanical and archaeozoological data obtained constitute an important background for the stelae discussed. Finds of cereal remains emphasise the fundamental role of this group of plants in the local agricultural economy. This is a phenomenon that persists both before the Roman period as well as in the final stage of Musti. The archaeozoological material, containing almost exclusively livestock remains, indicates a significant interest in farming. Environmental results, although related to the typical urban character of the site, indicate a significant attachment of the inhabitants of Musti to agricultural activities. The results of the environmental analyses seem to be consistent with the iconographic and epigraphic studies in many aspects.

Summary and conclusion

This article represents a comparative systematic study of historical, epigraphical, iconographic and eco-factual data from the Musti microregion and North Africa. This approach to the interpretation of past results is rare. To date, no such research has been conducted for nearby Dougga (Thugga), which has been systematically studied since the beginning of the twentieth century.Footnote 155 This may be due not only to the lack of archaeobotanical or archaeozoological finds, but also to the problem of identifying the presented plants or animals. Environmental research indicates a developed agricultural economy at Musti. It can be assumed that agriculture was mainly based on growing cereals and breeding animals, including pigs. Cereals, chiefly wheat, were used to make bread as a main part of the Roman diet. Livestock were the only sources of meat, and our research indicates that the diet was not supplemented with meat from game animals or fish.

The iconographic analysis of the studied stelae from the Musti microregion appears to correspond with the environmental research. Individual symbols, particularly depictions of fruits, vegetables and cereals, may be linked to the botanical remains discovered at the Musti site. Based on the faunal data that show the exceptional abundance of pigs, it can be concluded that the unique representation of two sows in iconography does not have to be an artistic vision or a reference to cult symbolism but rather an emphasis on the high availability of these animals in the local market and/or the fertility of the cereal microregion of Musti. It is not only about the exceptional representation of two sows on one face of a monument, but also the fact that in one of the stelae the sows hold some plants, possibly leaves like laurel leaves, in their mouths, a unique detail in African iconography: therefore, a microregional iconography (cereals, fruit, vegetables, loaves of bread, pigs) grounded in lived experience, lifestyle and agricultural production.

The functioning of the local community, in this case the priestesses of the Cereres, their families and stonecutters, was conditioned by the local economy, the availability of food products and the proximity of numerous private and imperial domains, and it also reflected the ritual practices of these priestesses. Their details are not well known, but the sacrifice of a sow certainly was an important part of that ritual. Although local stonecutters and sculptors adhered to cultural and religious conventions in presenting relief decorations, they had some creative freedom in their representations. The local environment, coupled with the desire to emphasise architectural and artistic uniqueness, probably played a significant role in inspiring their choices for the distinctive tombstone type and specific relief decoration. It cannot be ruled out that artistic inspiration may have also originated from the priestesses themselves or their family members. Unfortunately, the commissioners of these funerary objects remain unknown. We also know little about the priestesses themselves. Two of them, Ịuḷịa(?) O[—] and Iulia Rufina, belonged to the same family of Iulii. Vitellia L. f. Quartina was freeborn. Their Latin cognomina, Rufina and Quartina, are not exceptional, although the priestesses of the Cereres from Roman Africa also had Punic (Aemilia Amotmicar – CIL VIII 12335 = ILTun 649, Biricbal Iurat – AE 1935, 34) and Libyan names (Caecilia Zaba – CIL VIII 10575). While the set of four similar monuments from the Musti microregion is not as extensive a sample as the dozen or so high funerary stelae from the Bou Arada region, it provides valuable insight into the distinct stone-carving practice in the Musti microregion. In this context, the grand stelae with a rectangular base and triangular pediment stand out from other many tombstones (mainly cippi and high altars) of priestesses in Roman Africa.

The cult of Ceres was widespread on both sides of the fossa regia, especially in the Campi Magni cereal area.Footnote 156 Based on the geographic distribution of the epigraphic records of the priestesses of the Cereres, it can be concluded that their activities were concentrated on the western side of the fossa regia, in the former area of the Numidian kingdom (Africa Nova), where the protection of exceptionally fertile lands was most needed.Footnote 157 However, the popularity of Ceres distinguishes Musti and its microregion, particularly as regards the activities of the priestesses of the Cereres. The four grand funerary stelae of the priestesses, as well as the funerary cippus of sacerdos Cererum publica recently discovered by members of the Tunisian–Polish Archaeological Mission,Footnote 158 come from Musti and the immediate vicinity. The priestesses of the Cereres are not attested in the neighbouring cities of Uchi Maius and Thugga.Footnote 159 Although two women are confirmed in the latter city, Mundicia Fortunata sacerdos (CIL VIII 26447 = MAD 1579) and Vetula Saturnini sacerdos (CIL VIII 26477a = MAD 1607), it is not certain that they were priestesses of Ceres/the Cereres. They have single titles and their tombstones do not contain any additional relief decoration. Accumulation of richly decorated cippi of priestesses of Ceres/the Cereres similar to those of the Musti microregion can only be observed in other areas with developed agriculture, such as the Mactar region (ca. 50 km from Musti) and in the Bou Arada region (ca. 40 km from Musti).

Acknowledgements

The article was supported by the University of Gdańsk under the project UGrants-start, no. 533-U000-GS94-23. The archaeological work was conducted under the project ‘(Reading) African Palimpsest: The dynamics of urban and rural communities of Numidian and Roman Mustis (AFRIPAL)’, a grant from the National Science Centre (NCN), no. 2020/37/B/HS3/00348. The directors of the project are Jamel Hajji (National Heritage Institute) and Tomasz Waliszewski (University of Warsaw). The authors of the paper thank the Director of the Bardo National Museum, Mrs Fatma Naït Yghil, for permitting them to publish the photo of ILPBardo 435. The authors also thank Ridha Selmi, Magdalena Antos, Jakub Franczuk, Franciszek Ogidel and Konstanty Kowalewski for their technical support.

Abbreviations

- AE

– L'Année epigraphique. Revue des publications épigraphiques relatives à l'antiquité romaine, Paris 1888–.

- CIL

– Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum, consilio et auctoritate Academiae Litterarum Regiae Borussicae editum, Berlin 1863–.

- DFH

– Dougga, fragments d'histoire: choix d'inscriptions latines éditées, traduites et commentées, Ier–IVe siècles, eds M. Khanoussi, L. Maurin, Bordeaux 2000.

- EDCS

– Epigraphische Datenbank Clauss-Slaby.

- IlAfr

– Inscriptions latines d'Afrique (Tripolitaine, Tunisie, Maroc), eds R. Cagnat, A. Merlin and L. Chatelain, Paris 1923.

- ILAlg I

– Inscriptions latines de l'Algérie, vol. I. Inscriptions de la Proconsulaire, ed. S. Gsell, Paris 1922.

- ILAlg II,3

– Inscriptions latines de l'Algérie, vol. II,3. Inscriptions de la Confédération cirtéenne, de Cuicul et de la tribu des Suburbures, eds H.–G. Pflaum, X. Dupuis, Paris 2003.

- ILPBardo

– Catalogue des inscriptions latines païennes du Musée du Bardo (= Collection de l’École française de Rome 92), ed. Z.B. Ben Abdallah, Rome 1986.

- ILTun

– Inscriptions latines de la Tunisie, ed. A. Merlin, Paris 1944.

- IRT

– The Inscriptions of Roman Tripolitania, eds. J. M. Reynolds, J. B. Ward Perkins, Rome 1952.

- MAD

– Mourir à Dougga. Recueil des inscriptions funéraires, eds M. Khanoussi, L. Maurin, Bordeaux–Tunis 2002.

- PFOS

– M.-T. Raepsaet-Charlier, Prosopographie des femmes de l'ordre sénatorial (Ier–IIe s.), Lovanii 1987.

- RSAC

– Recueil des notices et mémoires de la Société Archéologique du Département de Constantine, Paris 1863.

- Uchi II

– Uchi Maius 2. Le iscrizioni, ed. A. Ibba, Sassari 2006.