Introduction

This paper is born out of an observation by two colleagues during Christmas and Lockdown that online trading platforms, which allow individuals to trade in company stocks and other financial assets, appear to have increased in number, their advertising proliferating via multiple channels such as the Internet, TV, and even on the sides of city buses. These adverts suggest that becoming a successful investor or trader is as easy as bidding on an online auction or playing a game. Yet, unlike other advertising for online games where money is at risk, there are no bright banners to ‘stop when the fun stops’.

The Cambridge Dictionary defines gambling as ‘the activity of risking money on the result of something […] hoping to make money’.Footnote 1 Arguably then, gambling and online trading by lay people are semantically very close, if not the same. Legally, traditional share trading and other areas of retail banking, as well as online gambling, are quite heavily regulated to protect customers. In this paper we will focus on how the existing regulatory framework applies to online trading, with an emphasis on the protection of certain vulnerable groups. The paper uses the broad definition of ‘vulnerable people’ cited in the 2016 guidance by the Solicitors Regulation Authority (SRA) as ‘someone who is at a higher risk of harm than others’.Footnote 2 This definition is chosen as it avoids the limitations and medicalisation of statutory provisions such as those in the Care Act 2014,Footnote 3 acknowledging the needs of various groups within the online trading context. Moreover, this paper acknowledges that some people who may traditionally fall within statutory definitions of vulnerability may not be automatically vulnerable in the online share trading space, whilst those who are not covered by statutory provisions may be considered vulnerable in these contexts.

We come to the paper's question from different perspectives: one of us with a research interest in online trading, who was surprised at the ease of opening a trading account and being able to risk large sums of money; the other is a researcher into disability equality law, who was concerned about the potential abuses of vulnerability that these platforms might facilitate. As far as we are aware, at the time of writing this is not something that has been considered previously in the literature. Here, we will outline the different regulatory approaches to personal online share trading and online gambling in order to argue that the potential social issues which exist and are responded to in relation to the regulation of online gambling (particularly for children and vulnerable adults), could also exist in relation to personal online share trading.

In light of the above, this paper has a double aim. First, given the relative infancy of these online trading services, the millions of consumers involved, and the pressures caused by the Covid-19 pandemic and lockdowns, we aim to kick-start academic discussion and research on the impact of online brokerage platforms, a much-understudied field. In addition to highlighting the issues, we suggest possible solutions which could be transposed or adapted from the gambling regulation framework. These, of course, can only be suggested as possibilities at this juncture, as further work will be needed to generate critical academic discussion and stakeholder engagement. Currently the statutory and regulatory frameworks around online share trading do not address vulnerable groups, but this is likely to become an emerging area in the future. Secondly, given the similarities between online trading and online gambling and the potential for exploitation of vulnerable people, the differing approaches to both legislative and industry oversight is quite startling. Therefore, the following sections will examine the difference in protection for children, vulnerable adults, and women in the online trading space, compared to online gambling, given that the same harms exist in these spaces in practice, including undue influence, lack of foresight to assess risk and financial losses.

In an ancillary manner we will also draw some inspiration from the case of Etridge (No 2), which was a threshold in recognising the existence of vulnerability on the basis of private relationships in the public financial sphere and required banks to recognise and guard against this as far as possible. Arguably, the private nature of online trading and access to online banking places vulnerable adults at similar risks to those identified in Etridge. However, these are not currently considered in online trading. In our opinion, the case of Etridge is analogous to the issues present in the online trading context, because both have the potential for female partners to benefit from the leverage or sacrifice of familial assets should the investment increase, but also to be left significantly disadvantaged should an investment fail.Footnote 4 This was acknowledged by the court and safeguards were put in place as a result in the context of face-to-face transactions. Online transactions present a greater possibility for undue influence or coercion, particularly for those in abusive relationships. This paper argues that the current failure to consider these issues in the context of online trading leads to a potential for new avenues for abuse.Footnote 5 Moreover, some of the measures taken to address vulnerability in the context of face-to-face banking could be replicated in the context of online trading in conjunction with gambling safeguards to offer a coherent approach.

It is also important to mention that the paper will not look at the liability of online financial services providers. The obligations of the providers of such services and the rights of their customers are set out in the Financial Services (Distance Marketing) Regulations 2004,Footnote 6 which implemented Directive 2002/65/EC of the European Parliament and the Council on the distance marketing of consumer financial services.Footnote 7 However, these legal instruments only provide a basic set of obligations for financial service providers that offer distance contracts, such as a list of information that has to be provided to the consumer before and after the conclusion of the contract, and the consumer's right to withdraw from the contract within 14 days. They do not provide any obligations specific to online brokerage platforms or any rights concerning vulnerable people. Furthermore, at the EU level, there is a larger ongoing debate on how to reassess the liability of online platforms in general,Footnote 8 the discussion of which would sidetrack the focus of this paper. The paper also acknowledges the literature concerning the issue of liability for hosting services such as social media for harms suffered online, but asserts that these contexts are fundamentally different to those discussed and is outside the remit of the current paper.Footnote 9

In order to achieve the objectives of the paper, in Section 1 we first provide an overview of online brokerage platforms and the services they offer, as for many readers these will be entirely new, and somewhat complicated concepts. This initial discussion is followed by an overview in Section 2 of the current UK regulatory framework for online trading services in financial instruments, with the aim of identifying certain weaknesses in the current frameworks when considering the aforementioned vulnerable groups. We decided to choose the UK's regulatory framework for two reasons. First, the UK is known for its high-quality financial services and its robust regulatory framework, engaging on a continuous basis in European and global discussions.Footnote 10 Secondly, we make a comparison between online trading and online gambling, drawing inspiration from the UK Gambling Act 2005.

Once we have identified the weaknesses in the current UK regulatory framework, we begin Section 3 by comparing online trading/investing with online gambling, and to a limited extent by also looking at Etridge (No 2). Such a comparison not only helps uncover potential loopholes in the current regulation of online trading, but also helps to provide solutions for the three vulnerable groups that we focus on. Based on these findings, in Section 4 we put forward several recommendations, before concluding.

1. Online brokerage platforms and the services they offer

Over the past couple of years, the number and size of online brokerage platforms have proliferated, mostly as a result of technological advancements that allow ‘retail’ traders and investors (the average members of the public) to open an account and start trading or investing. Various commercial ads on social media platforms, online newspapers, and even on the side of public transportation inform the public of the ‘great money making’ opportunities that lay ahead of them if they choose to use the platform. This positive message of financial gains is then followed by the fine print that more than two-thirds of people lose money when investing online.

A multitude of factors have contributed to the recent rise of online brokerage platforms. On the one hand, technological innovation has allowed brokerage firms to create user friendly interfaces, whilst the meteoric rise of various cryptocurrencies – coupled with quite aggressive advertising – has also induced millions of consumers to sign up to these platforms. On the other hand, the stock-market crash of March 2020 resulting from the Covid-19 pandemic, and the ensuing lockdowns have also contributed to tens of millions of people joining platforms such as eToro, Trading 212, or RobinHood.Footnote 11 Most of these online brokerage firms handle trades in various financial instruments and commodities worth billions of dollars.

The rise of online brokerage platforms has undoubtedly provided benefits to retail investors in the form of speedier, cheaper, and greater access to various financial markets and instruments,Footnote 12 increased supply of information, and the possibility to invest excess capital in times when interest rates on bank deposits are at historic lows. The recent GameStop (GME) scandal,Footnote 13 which ended up nearly bankrupting some of the most powerful hedge funds following the concerted action of thousands of Reddit users, has also sparked vivid discussions about the role of social media and online brokerage platforms in this financial battle between the proverbial David and Goliath.

Traditionally, customers would contact a broker who would then advise them on what assets to buy, when, and at what price, and of course when to sell those assets. With the exponential rise in computing technology, these former flesh-and-blood brokers have now turned into online platforms and mobile applications that allow customers to create an account and to begin trading or investing. A differentiation is made between day-trading, swing-trading and investing. In the case of the first two, the trader is interested in various short-term price movements of the financial asset, speculating on whether the price will rise or fall.Footnote 14 In the case of investing, the investor is much more interested in the fundamentals of a company or the long-term growth of an exchange traded fund (ETF) or a market index fund,Footnote 15 with the expectation of long-term holdings and dividends.Footnote 16

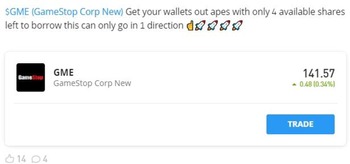

The brokerage platforms, often resembling popular social media platforms, offer a range of services. The extent to which some brokerage platforms resemble popular media platforms differs. EToro for example allows the trader/investor to customise the profile, to create an avatar, and to participate in online discussions – via comments and ‘Like’ buttons – with fellow traders or investors, in a fashion similar to the ‘Wall’ function of the social media platform Facebook. This is often accompanied by popular emojis that bring a somewhat lighter, almost game-like feeling to it, urging other users to buy a certain stock (see Figure 1, in which an eToro user is using a rocket emoji to urge other users to buy a specific stock). The layouts of other platforms, such as Trading 212, have a more professional feel to them. The platforms to a varying degree will also provide tutorial videos, the opinions of experts on certain financial instruments, and a range of technical analysis tools.Footnote 17

Figure 1. emojis used on online brokerage platforms, urging others to buy stocksFootnote 21

As mentioned, the platforms offer a wide range of financial products and instruments. Customers can trade or invest in stocks (company shares) listed on numerous stock exchanges worldwide, commodities (coffee, precious metals, grains, etc), foreign currencies (FOREX), cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, Ethereum, Ripple,Footnote 18 and ETFs. Some platforms also offer the chance to copy a popular investor's portfolio.Footnote 19 However, thus far, we have found no brokerage platforms operating in the EU or the UK that allow the trading of derivatives, such as futures and options.Footnote 20

The types of transactions that are available are also varied and, for some, the customer needs to open a separate account.Footnote 22 Customers can open a BUY position (when the customer bets on the price of the asset rising) or a SELL position (when the customer bets on the price of the stock falling, also called shorting). Depending on the platform, customers can also use ‘leveraged’ trading. When the trader/investor opens a position with a leverage of 1 (or 1x) the customer gains or loses the actual percentage change in the market price. In other words, if the price of the asset goes up 5%, the customer also gains 5%. However, when trading with a higher leverage, such as 3x, the customer's gain or loss is multiplied by the leverage chosen. Thus, the 5% gain or loss can turn into a 15% gain or loss.

Some underlying assets are owned outright by the customer (for example stocks opened with a BUY position and a 1x leverage), whilst other assets are traded as a Contract for Difference (CFDs). In the case of CFDs the customer does not own the underlying asset and the broker technically lends the ‘difference’ to the client. This is mostly the case with commodities, or when a BUY position is opened with higher leverage than 1 or when an asset is shorted (the customer bets on the price falling opening a SELL position). CFDs carry a lot more risk as the trader/investor might end up owing money to the broker. EToro currently uses an automatic stop loss of 50% for CFDs, meaning that the transaction is automatically closed if the CFD loses half of its value.Footnote 23 Furthermore, whilst many platforms claim to offer ‘free’ services, there are often hidden ‘fees’, such as slight differences between the market price and the broker's price or fees which are hard to find, such as those used for CFDs and for certain commodities.

Whilst these platforms have greatly improved access to trading and investing on the world's financial markets for the everyday person, they also carry real risks. The first risk is that not all platforms available online are regulated. One has to differentiate between regulated and unregulated online brokers. Regulated ones are authorised by a regulatory authority, such as the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA),Footnote 24 the Cyprus Securities and Exchange Commission (CySec),Footnote 25 or the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).Footnote 26 Because of these regulations, some platforms cannot offer their services in certain countries, or they cannot offer certain products or transactions. Unregulated platforms carry much greater risks, as they do not provide some of the guarantees offered by their regulated competitors. This paper focuses only on regulated platforms.

Secondly, whilst in the traditional interaction between the broker and the customer, the former could warn the latter about the potential risks surrounding an asset, on brokerage platforms it is the primary responsibility of the customer to diligently check each asset they invest in or trade. Different platforms will offer services such as the opinions of experts and various charts and graphs one can use to predict market movements. However, often this requires extensive technical knowledge and continuous market research, which the average person, especially a beginner, does not possess.

This leads to the third point, lack of knowledge. Most customers have never had experience in financial markets and are not even familiar with the basic terms, such as opening a BUY or a SELL position, or buying an asset with leverage or without, as a CFD or as an underlying asset. Thus, the potential to lose money is high. In fairness, most regulated platforms will offer the chance to first practise with virtual money, they will send volatility alerts and alert future customers that most people lose money when trading or investing. Nevertheless, new traders and investors are often confronted with a significant lack of knowledge and due diligence that is required when trading or investing in real assets with real money.

These are some of the immediate risks carried by these platforms. However, in this paper we will focus on the lack of protections for vulnerable groups, who – in our opinion – can easily be overlooked by the platforms and the regulators. Before turning to a more detailed analysis of the issues faced by vulnerable groups, let us briefly look at the UK regulatory framework and regulatory authorities; the FCA and the UK Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (FSMA 2000). We will also briefly mention the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) and the EU's MiFiD II framework, which have influenced the current UK regulatory framework.

2. The current regulatory framework in the UK: no references to vulnerable groups

In the previous section we discussed how one has to differentiate between regulated and unregulated brokers. In this section we will focus on the current UK regulatory framework in order to understand whether it covers online brokerage platforms and to check whether any provisions exist that are aimed to protect vulnerable groups.

As is well known, the UK has left the EU and the new UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement does not cover financial services.Footnote 27 Nevertheless, the existing UK legislative framework on financial markets, the FSMA 2000,Footnote 28 and various practices of the FCA have been greatly influenced by several secondary EU law instrumentsFootnote 29 and the practices of ESMAFootnote 30 prior to Brexit. Among the most important and recent EU instruments that have influenced the UK framework, one can mention Directive 2014/65/EU (MiFID II) on markets in financial instrumentsFootnote 31 and EU Regulation 600/2014 (MiFIR) on markets in financial instruments.Footnote 32

The UK has one of the most robust financial market regulatory frameworks and most of the online brokerage platforms operating in Europe are also authorised by the FCA. In the UK, the FCA is the conduct regulator for financial services firms and financial markets.Footnote 33 It was established on 1 April 2013, replacing the previous Financial Services Authority,Footnote 34 with a view to protecting consumers and financial markets, and promoting competition.Footnote 35 The strategic objective of the FCA is to make sure that the relevant financial markets function well. The FCA pursues three key objectives: consumer protection; integrity; and competition (FSMA 2000, s 1B). Besides the FCA, the Bank of England also acts as the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA), with the objective of promoting the safety and soundness of PRA-authorised persons (FSMA 2000, s 2B).

The FSMA 2000 is the primary legal instrument in the UK for the regulation of financial markets. The activities regulated by the FSMA 2000 mainly relate to an ‘investment of a specified kind’, investment including any asset, right or interest (FSMA 2000, s 22). Various legal and natural persons can make an application to the FCA to carry out one or more regulated activities (FSMA 2000, s 55). Among the most popular platforms in Europe, eToro and Trading 212 are also authorised by the FCA. However, very recently the FCA prohibited one of the biggest online platforms for the trading of crypto currencies, Binance, from undertaking any regulated activities in the UK.Footnote 36

If the FCA concludes that a person is performing a controlled activity without approval, it can impose a penalty of such amount ‘as it considers appropriate’ (FSMA 2000, s 63A), a power which it has used in the past.Footnote 37 The FSMA 2000 also includes detailed rules on the listing of securities (Pt VI), the control of business transfers (Pt VII), market abuse (Pt VIII), and short selling (Pt 8A).

Pursuant to Pt XV of the FSMA 2000, the Financial Services Compensation Scheme was set up. The Compensation Scheme is meant to pay compensation to a claimant, in case the firm used for financial transactions has gone out of business.Footnote 38 If the firm failed after 1 April 2019, the person is eligible to receive compensation up to £85,000 per firm.Footnote 39 In other words, if a client has a trading or investing account with two online brokers, in case of the default of both brokers, the client is covered up to £85,000 for each broker. The FSMA 2000 also includes provisions on an Ombudsman Scheme to settle certain disputes (Pt XVI), consumer protection (Pt 16A), recognised investment exchanges and clearing houses (Pt XVIII), and the suspension and removal of certain financial instruments (Pt 18A).

Pursuant to s 347 of the FSMA 2000, the FCA also needs to maintain a record of every authorised operator, which must contain a set of minimum information about the operator. For this purpose, the FCA set up the Financial Services Register,Footnote 40 where one can check whether the online financial services provider is authorised by the FCA. The FSMA 2000 also includes provisions on illegal money lending (Pt 20B), provisions on auditing (Pt XXII) and insolvency (Pt XXIV). The website of the FCA is also quite informative and is meant to provide useful information, including on how to avoid scams by unauthorised operators.Footnote 41

The FCA provides further protections for consumers. For example, s 7.13 of the Client Assets Sourcebook (CASS) requires operators to segregate a client's money from the firm's own money as a way of protecting the client's assets.Footnote 42 In 2015 this system was strengthened by the Financial Reporting Council, which developed new, mandatory assurance standards for the safekeeping of clients’ assets.Footnote 43

Furthermore, in 2019, ESMA made temporary restrictions on the trading of contracts for difference (CFDs). The FCA decided to follow ESMA's rules and make the restrictions permanent. Thus, brokers are required to limit the amount of leverage that retail clients can use (between 30:1 and 2:1), and if the client's CFD position falls to 50% of the margin needed to maintain the position open, the broker must automatically close the position.Footnote 44 As mentioned in Section 2, whenever the customer opens a leveraged CFD position, they technically borrow money from the broker to cover the difference. This means that if the value of the trade falls below a certain value, the customer could owe money to the broker. Following the new rule, the CFD position is automatically closed at a loss of 50%.

However, whilst the current regulatory framework seems quite extensive, there are some more critical observations that need to be made. First, according to Chiu and Brener, the current regulatory framework does not adequately protect retail customers in non-advisory, ‘execution-only’ contexts (when the financial service providers act only as intermediaries, such as online brokerage platforms), except for the financial service provider's communication duties.Footnote 45 Furthermore, they argue that the FCA's enforcement policy and practice contains several deficiencies, such as issues concerning transparency, consistency, and effectiveness.Footnote 46

Secondly, there is also a lack of rules on vulnerable groups in the current regulatory framework. In order to address this second point, after we had mapped out the UK regulatory framework, we proceeded to check whether the FSMA 2000, the CASS, and the Financial Compensation Scheme included any provisions on vulnerable groups. Our search did not find any provisions concerning such groups. We had also contacted the FCA to check whether we might have missed some other regulatory sources, but we were told that we had covered the relevant framework.

We then thought that the silence on vulnerable groups might have been a result of a possible faulty implementation or transposition of the previously mentioned EU measures, the MiFID II Directive, and the MiFIR Regulation. Therefore, we proceeded to check the EU measures in detail as well. Whilst we did not find any specific mentions of vulnerable groups, we did come across two EU provisions that could be useful for vulnerable people based in the EU. Pursuant to Article 24(5) MiFID II, ‘investment firms’ must provide information to their clients in a comprehensible form, so they can reasonably understand the nature and risks of their investments. Furthermore, Articles 12–13 of MiFIR provide for the obligation of the operators to ensure non-discriminatory access to pre- and post-trade data. One could interpret this provision to include people with certain disabilities. Having this information, we then proceeded to re-check the UK regulatory framework, but we did not find the UK equivalent of these EU provisions. We did discover that the FSMA 2000 in s 87A includes as a criterion for the approval of a listing prospectus by the FCA that the prospectus be ‘presented in a form which is comprehensible and easy to analyse’. However, this obligation refers to the listing of securities in UK regulated markets, such as the London Stock Exchange, and does not include a general obligation such as the one found in the EU regulatory framework.

In conclusion, the current regulatory framework in the UK – inspired also by the EU regulatory framework and the work of ESMA – offers quite extensive protections. The rules on transparency were strengthened, brokers need to be authorised to perform their activities, and in the case of the brokers’ insolvency the customers can receive compensation up to a certain level. Furthermore, the client's money is segregated from that of the firm, and the detrimental effects of CFDs and leveraged trading are mitigated for retail customers. Nevertheless, the UK regulatory framework overlooks vulnerable groups and does not include safeguards for children or people with disabilities.

3. Potential implications

(a) Gambling versus online trading: the question of vulnerability

In Section 2 we discussed how the current UK regulatory framework for trading and investing in financial assets overlooks certain vulnerable groups. In this section we draw a comparison between online trading and online gambling, highlighting how the current UK regulatory (the Gambling Act 2005) and policy framework for online gambling protects certain vulnerable groups. From this comparison, we draw inspiration for potential solutions in Section 4.

Section 3 of the UK Gambling Act 2005 defines ‘gambling’ as gaming, betting, or participating in a lottery. As mentioned in Section 1 above, when it comes to financial assets, one can differentiate between investing (long-term) – when the investor is interested in the long-term prospects of a company – and trading (short-term) – when the trader is interested in the short-term price movements of a financial asset. However, regardless of the time scale, in both situations the investor or trader is ‘betting’ money on certain price movements of the underlying asset with the expectation or hope of making money. Thus, both investing and trading would meet the dictionary definition of gambling, the difference being the time horizon. The best way of mitigating the detrimental effects of certain price movements is by diversifying one's portfolioFootnote 47 into multiple assets and sectors of the economy.Footnote 48 This ensures that a potential downturn affecting one economic sector or one financial asset will only affect a small part of the portfolio. Contrary to this, a bad strategy is to invest one's entire money in one asset or one economic sector. This is no different from gambling, and one often sees retail traders ‘bet’ all their money on one asset or one economic sector.

The following sections examine the difference in protection for children, vulnerable adults and women in the online trading space, compared to online gambling, and in an ancillary manner also drawing inspiration from Etridge (No 2).

(b) Children and young people

The involvement of children and young people in both online and ‘bricks and mortar’ gambling is heavily scrutinised and regulated in the UK. Indeed, the UK Gambling Act 2005, s 1(1) states that: ‘In this Act a reference to the licensing objectives is a reference to the objectives of […] protecting children and other vulnerable persons from being harmed or exploited by gambling’. Furthermore, s 46 of the Act states that a licensee commits an offence if they ‘invite, permit or cause a child or young person to gamble’ outside of certain conditions, including non-commercial betting, licensed family venues and fairs and playing in a lottery.Footnote 49 However, in April 2021, the UK Government raised the age limit for participating in the National Lottery to 18 years of age in order to standardise the approach to harm prevention.Footnote 50 Section 24 of the Gambling Act 2005 also requires the Gambling Commission to produce Codes of Practice to meet the needs of vulnerable people and address harms. In 2021, the Advertising Standards Agency (ASA) published a report on the need to ensure that guidelines are updated in order to limit children's exposure to gambling adverts in light of a shift from television to social media exposure.Footnote 51 There has also been a move to block the inclusion of gambling adverts from websites which do not have age barring or log-in criteria.Footnote 52 Moreover, a 2019 Regulatory Statement from the Committee of Advertising Practice (CAP) referenced a variety of research over recent years highlighting the impact of online gambling on children and young people. According to the Statement, 7% of respondents between 11–16 years of age had spent money that they were not otherwise planning to on gambling as a result of [emphasis added] social media advertising exposure.Footnote 53

In the context of online trading, though people under the age of 18 are unable to hold a trading account in their own name that is not to say that they could not gain access to these accounts. As the majority of applications for trading accounts rely on self-declaration and the upload of supporting documentsFootnote 54 there seems to be very little material scope by which service providers could prevent a child from accessing a trading account should they be able to persuade a family member to open an account on their behalf or by using the documents of an adult family member. Research into online gambling indicated that 7% of respondents to a 2017 Gambling Commission study had gambled online on their parents’ account.Footnote 55 Moreover, some providers of investment accounts, such as Hargreaves Lansdown, offer the ability for guardians to open a trading account on behalf of a child online, with the proceeds held in a Bare Trust until the child reaches the age of 18.Footnote 56 Whilst such accounts require a parent or guardian to open the account on the child's behalf, the fact that the application process is entirely online means that there is little that the service providers could do to ensure that the children are not making the trades themselves. Furthermore, the fact that accounts are offered for the benefit of children may lead guardians to believe that there is an element of a ‘halo effect’, for example that children's engagement with them is less likely to be harmful. Kolowski identified the existence of the halo effect in terms of banking behaviour in their research into consumer perception of their bank's performance compared to others.Footnote 57

Whilst no such statistics currently exist for the use of online trading platforms amongst children in the UK, many similar tactics are used in both the advertising and set-up of online brokerage sites as with gambling advertising on social media. For example, the trading platform eToro advertises itself as a ‘Social Trading Platform’Footnote 58 and utilises many of the same functions as social media sites, including animation, chat, emojis (see Figure 1) which are likely to be attractive, familiar and reassuring to younger users, which may keep them online.Footnote 59 Long-time investors, such as Michael Burry,Footnote 60 have recently criticised online trading apps, such as Robinhood, as a ‘dangerous casino’ that gamify trading and investing.Footnote 61

Additionally, young people's confidence in using social-style platforms may also make them less aware of or able to navigate or identify potential sources of riskFootnote 62 in terms of their choices and behaviours. In turn, this may make them more vulnerable to investing higher amounts than they can afford or intend to risk (for example by using higher leverage, as explained in Section 1), as social media perpetuates images of perfection to users.Footnote 63 This is also perpetuated by external social media such as Youtube, including videos with titles such as: ‘Meet the 10-year old investors that are learning how to beat the market’, ‘Yes, even kids can invest in the stock market’, ‘Whiz Kid Makes $300,000 Trading Penny Stocks’, and ‘13 Year Old Made $78,000 TRADING Stock Options’.Footnote 64 The catchy titles and the short duration of the videos create the illusion that day trading and investing are a quick way of making money and are risk free. Instagram has also been utilised by traders to peddle a lifestyle of luxury to young people through extravagant images and hashtags as part of Binary Option products trading,Footnote 65 which are highlighted by the FCA as highly volatile with 82% of monies being lost.Footnote 66 This is evidenced by the fact that prior to January 2018 these products were regulated by the Gambling Commission, rather than the FCA.

Social media offers a way for young people who have been enticed by the images of success to buy into these products and services, but who eventually lose money to gain it back by signing up to become influencers themselves and earning commission on the numbers of people that they too sign up by using the same tactics. The sale of binary trading options was banned in the UK in April 2019 in response to the high levels of fraud and exploitation of young people.Footnote 67

Evidence of the harm which might be caused to young people by engaging with online trading platforms can be seen in the case of a 20-year-old American student, Alex Kearns, who committed suicide after mistakenly believing that he owed $730,000 to the broker on the Robinhood trading platform, following an automated reply from customer services when he asked for clarification.Footnote 68 His parents brought a civil lawsuit accusing the platform of negligently targeting inexperienced customers and failing to ensure that they had sufficient funds to cover the cost of the trades made.Footnote 69

Under the proposed online safety legislation in the UK, there is possibility that similar cases could be brought against companies in the UK. In December 2020 the UK Government released the Online Harms White Paper, which outlined plans for new legislation of accountability and oversight for online and tech companies in keeping children and vulnerable people safe online.Footnote 70 The paper focused specifically on addressing criminal conduct, as well as the prevention of suicide and self-harm.Footnote 71 Reference was also made to the framework already in place to mitigate the potential harms of online gambling,Footnote 72 however, no reference was made to the online trading of financial assets. Nevertheless, the proposed Online Safety Bill will apply to online marketplaces, which may offer some protection, but the application of the proposed Bill to online trading is not yet clear.Footnote 73 Therefore, it is crucial that these issues are considered in order to meet the duty of care imposed by the proposed Online Safety Bill and also to prevent the courts being overwhelmed with cases.

(c) Vulnerable adults and those with disabilities

By virtue of s 24 of the Gambling Act 2005, the Gambling Commission also has a remit to produce codes of practice to ensure that vulnerable adults and those with disabilities are not disproportionately harmed by gambling.Footnote 74 In response, the industry has developed a number of initiatives such as Gamble Aware,Footnote 75 self-exclusion measuresFootnote 76 and preventing the use of credit cards to fund online gambling.Footnote 77 The Royal College of Psychiatrists in the UK highlights the link between existing mental health conditions and problem gambling.Footnote 78 National Health Service England data indicates that:

The number of gambling related hospital admissions has more than doubled in the last six years from 150 to 321. Cases of pathological gambling, where people turn to crime to fund their addiction has increased by a third in the last 12 months, bringing the total to 171. The steady rise in admissions has prompted the NHS to commit to opening 14 new problem gambling clinics by 2023/24.Footnote 79

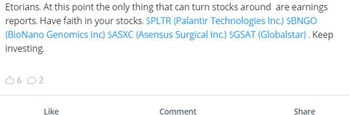

Online gambling and online trading behaviour can be linked by the concept of ‘Fear of Missing Out’ (FoMO). Online trading and increased access to ‘live’ investment information and tips (see Figure 2) via mobile phones, increases the impact and sense of FoMOFootnote 80 around trading decisions and lowers the perception of risk.Footnote 81

Figure 2. one user sharing his tips with other users

Li and Griffiths also identified that ‘individuals with high levels of FoMO were more likely to show impulsivity and spend a longer time gaming, and these factors were associated with Gambling Disorder’.Footnote 82 An American study into problem gambling online amongst teenagers highlighted excitement-seeking as a key component in the development of problem gambling behaviours.Footnote 83 The link between dopamine and excitement is well documented,Footnote 84 whilst a 2012 study of successful Wall Street traders indicated that the 60 subjects had:

[…] a genetic profile associated with balanced levels of dopamine, and also linked to moderate but not high risk-taking behaviour. Thus, successful traders do not appear to take extraordinary risks and also appear to take a longer-term perspective.Footnote 85

In addition to the potential comorbidities between mental health conditions and problem gambling, in guidance to practitioners the Law Society highlights that financial abuse of people with disabilities and vulnerable adults is increasing due to factors such as social isolation and advances in technology.Footnote 86 As discussed, some of the major trading platforms operating in the UK have seen tremendous increases in their customer numbers during the Covid-19 lockdowns, their customers now often numbering in the tens of millions.

Financial abuse and ‘mate crime’ are significant concerns for vulnerable adults and those with disabilities. The UK Care Act 2014 defines financial abuse as: ‘having money or other property stolen, being defrauded, being put under pressure in relation to money or other property, and having money or other property misused’.Footnote 87 Financial abuse can also encompass ‘mate crime’, which occurs when a person with a disability is brought into ‘fraudulent friendship’Footnote 88 by parties without disabilities in order that they might gain a benefit.

Additionally, the Covid-19 pandemic has led to a change in the way in which vulnerable adults are accessing financial services, moving to distance means of use. However, difficulties still remain. FCA data indicates that:

Adults with poor mental health or low mental capacity or cognitive difficulties: 42% of these people found dealing with customer services on the phone confusing or difficult; 30% of adults with physical disabilities found dealing with customer services on the phone confusing or difficult. Adults with a hearing or visual impairment: 40% of these people found dealing with customer services on the phone confusing or difficult; and 25% struggled to follow instructions which makes it hard for them to interact with financial services providers.Footnote 89

As with the points raised concerning children and access to trading accounts due to online applications, there appears to be little that could be done in practice to prevent people being coerced into providing funds or opening an account for online trading purposes. As with the previous section, this highlights the incongruity between the regulation of gambling-related and other transactions and online trading.

The issue of ensuring that people with disabilities are not exploited by online trading platforms must also be balanced with not automatically excluding them from taking part due to paternalistic attitudes around disability and the ability to enter into contracts. This is evident from Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) 2006. The UK ratified the CRPD in 2009.Footnote 90 Varney argues that focus should shift away from the medical perspectives on disability to focusing on the context of the transaction and other factors which could apply to anyone without a disability.Footnote 91 This focus on context is also particularly important in relation to potential ‘mate crime’ because if the trades were to be carried out by a person without a disability, but with misappropriated funds, obtained under the pretence of a friendship, such as one friend helping out another or via duress, the incapacity defence would be unlikely to succeed, as the person making the trades would have capacity. Yet the person who suffered the loss and risked the capital, without the potential to gain from this, may not.

Focusing on the needs of people with disabilities could also improve the transparency of these platforms generally, because the CRPD emphasises that people with disabilities need to be supported in exercising their legal capacity with access to clear information expressed in multiple formats and ordinary language.Footnote 92 This may be able to combat the use of small print and overly complicated terms and conditions, which could benefit all users, by increasing clarity and as a result awareness of risks. Easy read documents, characterised by simple language, supported by imagesFootnote 93 could be useful in achieving this.

The UK also created web accessibility standard ISO 30071-1, which is the most recently published standard and is meant to assist private companies with making their websites accessible to people with disabilities and understanding the business case for this.Footnote 94 Whilst there has not been any litigation between consumers and businesses with regard to the accessibility of their websites, inaccessible websites could lead to a claim in discrimination under the UK Equality Act 2010, s 20, if a potential claimant could argue that failure to make ‘reasonable’ adjustments to remove barriers to access left them at a substantial disadvantage compared to those without a disability. In 2012 the Royal National Institute of Blind People settled out of court with the now defunct travel company, BMI Baby, for their slow progress in ensuring accessibility on their website.Footnote 95 The failure of platforms to question potentially exploitative transactions or to ensure accessible information could lead to a successful discrimination claim.

(d) The potential for undue influence and coercion in domestic relationships

Finally, the lack of regulation of online trading also appears incompatible with the impact of Royal Bank of Scotland plc v Etridge (No 2). This case dealt with a number of appeals brought by women who had been coerced or persuaded to agree to leverage the family home as surety for loans to support the development of their husbands’ businesses. As a consequence of the ruling, under certain circumstances lenders are ‘put on notice’ of the possibility of undue influence and must ensure the surety has received independent legal advice. This legal advice must cover: the possibility of losing the asset, should the business fail to prosper, including the possibility of bankruptcy; the full value of the loan being taken out and its relation to the available assets; that the party understands that the lender may vary the terms of the loan; checking that the client agrees to the terms of the loan and for this to be communicated in writing to the bank; discussing the possibility of limiting the amount borrowed; ensuring the party not requesting the loan can access guidance in non-technical language without the borrower present; and that the non-requesting party understands that they do not need to agree to the loan.Footnote 96

The issues raised in Etridge about the need to safeguard vulnerable clients from undue influence could be similarly applied in the context of online trading, because both banks and online trading platforms receive transfers of money, which can be complicated by familial relationships – albeit for different reasons –placing clients at risk of coercion. The similarities between the contexts and the potential for issues and the judicial and industry response of instituting safeguards highlights that this issue is worthy of consideration in the context of online trading.

Currently, there is no facility on online trading platforms to ensure that the users are not leveraging family assets by using undue influence on partners, nor is there a way currently to ensure that any such partners receive independent advice. Moreover, in 2014 the UK Citizens Advice Bureau suggested that ‘tighter checks on lending, particularly online, in relation to credit taken out under duress’ could assist in combatting financial abuse.Footnote 97 This issue demonstrates Auchmuty's argument in response to the Etridge ruling and the need to consider that women face financial vulnerability both inside and outside of the private sphere, meaning that ‘the solutions to women's problems with undue influence and misrepresentation lie outside the realm of law’.Footnote 98 She is supportive of Richardson's idea of awareness-raising campaigns to empower women to know their rights and to say ‘No’ to their partners when necessary.

In 2019, Finance UK published a multi-agency and stakeholder-created awareness-raising document, outlining what constitutes financial abuse and explaining clearly what protections can be put in place and how to ask for help.Footnote 99 This could be replicated on online trading platforms, by placing awareness-raising messages as to the criminal nature of coercive control and financial abuse as outlined by s 76 of the UK Serious Crime Act 2015, as well as providing links to resources to those suffering financial abuse to get help on their websites.

4. Ways forward

There are a variety of avenues which could be utilised to address the issues raised. Therefore, we suggest a mixed approach, involving stakeholder engagement, legislative reform and raising public awareness. These solutions could also have positive effects for business by avoiding unnecessary litigation and payment of damages, or damage to reputation and scrutiny,Footnote 100 and maintaining consumer confidence and engagement through transparency.Footnote 101 In the following sections we will first highlight potential practical hurdles, followed by whether new obligations for brokers could be created and, if so, what types of obligations.

(a) Practical hurdles

The first question is whether legislative change is needed or whether other solutions can also be pursued, possibly combining both legislative and non-legislative measures. If one were to pursue the legislative path, then the most likely solution would be to amend the current FSMA 2000 to include new obligations (see Section 4(b)) for financial service providers and brokers.

There are two potential problems with this approach. First, some push-back from the industry is expected, but then again, the FSMA 2000 is not immune to amendments, as most recently shown by the changes needed due to the UK leaving the EU.Footnote 102 Secondly, and more importantly, this approach is reactive in nature. Due to the incredible speed at which online financial services are changing, the regulator will be one step behind. Nevertheless, there is still ample room for the regulator to step in. By way of example, very recently the FCA did not allow the online cryptocurrency trading platform Binance to carry out regulated activities in the UK.Footnote 103

The amendment of the Online Gambling Act – so as to include online trading – remains a theoretical possibility, as it would be extremely difficult to achieve this in practice. Given the negative associations between online gambling and trading, one would expect heavy pushback from the online trading industry. A more plausible solution would be to include in the proposed Online Safety Bill provisions on vulnerable people and online trading. However, as discussed in Section 3, not all solutions need to be legislative in nature. Public awareness campaigns or the interpretation of terms such as ‘reasonable’ or ‘non-discriminatory’ access to information by the judiciary could also result in the increased protection of vulnerable groups.

In the next section, let us look at the types of substantive obligations and safeguards that could be included. The majority of these are also being considered by the UK Government as part of the drafting process of a new Gambling Act, expected later in 2021. At the time of writing, data from the Call for Evidence for the new Act had yet to be published.

(b) A set of new obligations for online brokers?

Rather than considering the suggestions made here as new obligations, which may at first appear onerous, this question should be approached from the perspective that, much as the gambling industry has had to do in recent years, the brokerage industry needs to adapt to the new realities and possibilities of the online space, whilst at the same time accepting that these are coupled with responsibilities and duties. Such a shift is positive for industry and consumers alike as a responsive and dynamic regulatory framework keeps the market moving and confidence high.

(i) Children and young people

The industry could focus on lowering the appeal of online trading platforms for children and vulnerable young people by altering the interfaces of the sites to remove game-like aspects such as emojis and chat functions which are attractive to younger users. Existing advertising rules for gambling could also be used to prevent children from being enticed to access such content, by regulating the use of images and endorsement outside of age-restricted sites, where log-in details are required.

Furthermore, to prevent further issues such as the suicide of Alex Kearns, trading platforms could be prevented from allowing users to fund their trades through credit, much in the same way that online gambling platforms no longer permit customers to use credit cards on their sites. Trust accounts for children under the age of 18 could also be rebranded to remove any potential halo effect or residual belief that the accounts are suitable and safe for children.

In terms of legislation, Part 4 of the Gambling Act 2005, relating to children, could include a definition of gambling which mirrors that of ordinary language, which could thus include online trading (see Section 3 above). However, as we have highlighted, this is unlikely to be popular with brokers, so perhaps a better system might be to take a non-legal approach which focuses on corporate responsibility, harm prevention measures and awareness raising, similar to the approach taken in the gambling sector.

Regulatory bodies and legislation in relation to online trading could also clarify the position of vulnerable people, perhaps creating a system of fines for failure to safeguard. These fines could be used to fund compensation and corporate responsibility initiatives. With regard to the narrative on social media platforms, such as YouTube and Instagram, the application of the rules on online and social media marketing and selling could be widened. Currently, social media influencers who are advertising products must be transparent about whether they have paid for the products or have been sponsored to discuss them. If these rules were expanded to advertising for online trading platforms it could prevent children and young people being enticed to participate in these platforms as a way for young people to make money, as seen in the Wolves of Instagram article.Footnote 104 Such measures would go some way to prevent the proliferation of the image of online trading as a risk-free, easy way to make money. Platform guidelines could also be updated to prevent users uploading content relating to children investing online. Additionally, charities and banks could work with children and schools in order to educate children and young people about advertising strategies on social media and the realities of trading online. For example, Barclays Bank already offers a range of financial and technology education programmes within the community.Footnote 105

Ultimately, a combination of both legislative measures – such as the proposed UK Online Safety Bill – and soft measures, such as commitments to codes of practice, the creation of professional associations as well as cross sector and stakeholder forums could create a unified response. The Fair Banking Foundation could provide a model for such an approach, as it offers a cyclical approach to research and industry innovation and cooperation which could be applied to the online brokerage sector.Footnote 106

(ii) Vulnerable adults

The physical meetings suggested by the Etridge ruling as a means of preventing undue influence and financial abuse may not be feasible in relation to online trading, due to the varied geographical locations of both customers and companies. However, there are methods that have been introduced by certain banks during the Covid-19 pandemic that could be used by the online trading platforms. Examples include dedicated telephone lines and contacts with vulnerable customers as well as increased checks on unusual or third-party transactions, where permission has been granted during the pandemic.Footnote 107 This could facilitate a coordinated approach between banks and trading platforms. In practice, both parties could monitor the activity of customers, much in the same way that banks offer support and assistance messages when large sums of money are transferred between accounts. Footnote 108

When an unusual or large transfer is made to an online trading platform, the bank could call the customer to check on their welfare and well-being.Footnote 109 They could ask the customer a series of ‘yes’ or ‘no’ questions in order to ascertain whether the transaction has been made under duress. A similar tactic has been utilised by both police and health practitioners to enable people to disclose domestic abuse in safety.Footnote 110 The operator could ask, ‘Do you feel safe?’, ‘Has someone asked you for this money?’, ‘Do you want to spend this money?’, or ‘Do you need help?’. Depending on the answers to these questions the bank can then authorise the payment or contact the police or social services safeguarding team, making a vulnerable adult referral.

Under the Care Act 2014, s 42 each local authority must make enquiries – or cause others to do so – if it believes an adult is experiencing, or is at risk of, abuse or neglect. An enquiry should establish whether any action needs to be taken to prevent or stop the abuse or neglect and, if so, by whom. Financial abuse including theft, coercion and misuse of property is outlined as a ground for investigation. This could be supported by a cross-industry drive to fund or support the training of dedicated financial abuse safeguarding teams within the sector, which could work with local authority districts. Online trading platforms could also monitor account activity, as well as removing credit facilities from customers on the sites as well as preventing trades being funded by credit cards, in the same way that online gambling platforms have committed to. The trading platforms could form a representative organisation, like the UK Gaming and Gambling Commission, focused on education, awareness raising and support. This could also have telephone support lines, similar to Gamble Aware. Furthermore, online trading platforms could also operate ‘self-exclusion’ periods on their sites, to enable traders to cool off if they feel their activities are spiralling out of control.

The sector is beginning to recognise and respond to the needs of vulnerable clients and the impact of financial well-being generally. The FCA has issued guidance on assisting vulnerable customers, focusing on the barriers that they face when interacting with financial services providers. These include factors such as intimidating phone manner, lack of empathy and sympathy to the difficulties customers face, lack of knowledge from staff about the needs of those with disabilities or other vulnerabilities, being passed between departments or colleagues and a lack of relationship building. In response, FCA regulated service providers are encouraged to ensure that their staff receive training in communicating appropriately with vulnerable customers.Footnote 111 These existing materials and guidelines could be adapted and built upon to provide training for online trading platform staff. Moreover, companies could work in tandem with representative organisations such as Disability Rights UK, Mencap, Royal National Institute of Blind People, Royal National Institute of Deaf People (RNID), Age UK, Autism UK and Mind, Womensaid and Menkind, to create staff training and customer-facing resources to increase awareness of potential issues and abuse in the online space. They could work together to develop a public awareness-raising media campaign.

Online trading platforms could also focus on the accessibility of their websites for people with disabilities at the point of build and design. Information relating to sign-up and risks of engaging with the platforms should be clearly written and presented to ensure that all users can understand it and find sources of support where necessary. There could also be an option for those with additional needs to ask for a telephone or videocall to discuss their needs and to provide any support they might need when using the site. The operator could also discuss potential issues on financial abuse or other issues as appropriate.

Conclusion

This paper had a double objective. First, to start academic discussion and research on the impact of online brokerage platforms, a field which is very new and understudied. Secondly, to highlight several potential side-effects of the rise of online trading platforms, by focusing on vulnerable groups.

We hope that this paper will spark further discussion on a very recent but increasing phenomenon. The recent advances in information technology now allow millions of people to trade and invest in an array of financial assets, allowing them to have more control over their own financial well-being, arguably a positive development. Nevertheless, trading and investing with real money comes with serious risks, especially for vulnerable people. The current UK framework for the regulation of online trading in financial assets overlooks vulnerable groups, such as children, disabled adults, and vulnerable women. By drawing a parallel between online gambling and online trading, the negative effects of online trading can be minimised. The UK regulatory and policy framework surrounding online gambling could provide the UK with valuable solutions to tackle the existing lacunae in the protection of vulnerable groups in the online trading environment.