‘The sincerity of [the] apology will be determined by how far the Home Office demonstrates a commitment to learn from its mistakes by making fundamental changes to its culture and way of working, that are both systemic and sustainable’.

– Windrush Lessons Learned Review (HC 93, March 2020).Introduction

It is difficult to imagine a more important document than one which proves the entitlement to reside in a particular state: it is used as the manifestation of the ‘right to have rights’.Footnote 1 This was vividly illustrated recently by the infamous Windrush scandal, which saw – on the basis of problems proving the right to reside – lawful residents of the UK wrongly detained, denied legal rights, threatened with deportation, and, in at least 83 instances, deported from a country they were entitled to call home.Footnote 2 The Home Office, following an extensive review, promised to learn lessons.Footnote 3

By 31 March 2021, there were almost 4.5 million individuals reliant on digital-only proof of their entitlement to reside lawfully in the UK.Footnote 4 In practice, this means that those individuals can only access and share proof of their immigration status online, including when they want to rent a property or apply for a job. Based on government strategy, the number of people with digital-only proof of status will increase significantly in the coming years.Footnote 5 This represents a major turning point in the emergence of digital administration, both generally and in the context of immigration policy.Footnote 6 Politically, the policy has been controversial – being the subject of multiple pressure group campaigns and leading to a confrontation between the House of Lords and the House of Commons.Footnote 7

Our central argument in this paper is that digital-only status – at least in its current, blanket form – is unlawful because it is indirectly discriminatory.Footnote 8 Using the EU Settlement Scheme (EUSS) as a case study, we show in detail how digital-only status disadvantages various groups with protected characteristics – namely, disability, age and race – in a way that is not proportionate to its underlying objectives.Footnote 9 This argument has profound consequences both for the current operation of digital-only status in the EUSS, and for the Government's plans to roll it out across the broader immigration system. Ultimately, without adjustment, the policy risks separating people from their proof of residence, further extending discriminatory practices already within the immigration system,Footnote 10 and giving rise to a digital version of the Windrush scandal.

We make this argument in four parts. First, we introduce how digital-only status operates, which is necessary to understand why its effects are discriminatory and thus unlawful. Secondly, we show – using three composite profiles with different protected characteristics – how digital-only status, at least in its current form, can seriously disadvantage certain groups of people. Thirdly, we argue that all attempts to eliminate these disadvantages have been inadequate. Finally, we show that the policy justifications for digital-only status do not sufficiently justify its discriminatory effects and, moreover, less discriminatory measures that achieve the same objectives are available.

1. Digital-only status: the case of the EUSS

It is important to begin by setting out clearly how digital-only status works. We focus on a specific case study – digital-only status within the EUSS – for two reasons. First, the discriminatory effects of digital status are rooted in the details of its design and implementation. It is possible to imagine such a policy being operationalised in different ways, some of which may well be lawful. It is helpful, therefore, to anchor the legal analysis of digital status in a specific case. Secondly, at present, the EUSS is most prominent example of digital status in the UK. It is embedded in a new and ambitious immigration scheme which has given status to approximately 4.5 million EEA nationals. This digital-only status is the only proof of an individual's right to enter, stay, work, rent and access services in the UK and will stay with them for many years, potentially their lifetime, unless they decide to naturalise as a British citizen in the future. It is also likely to be the template for the Government's planned expansion of this mode of status in the coming years. Problems with digital status within the EUSS are likely to flow through to the broader immigration system in the near future. It is this scheme that we refer to and focus our analysis upon in the remainder of this paper.Footnote 11

The EUSS is the system established to allow EU citizens to apply to remain in the UK after Brexit.Footnote 12 The Withdrawal Agreement between the EU and the UK requires this new residence status to be accompanied with a document evidencing that status and makes clear that the proof ‘may be in a digital form’.Footnote 13 Through the EUSS, the UK opted to provide European Economic Area (EEA) and Swiss nationals who get settled or pre-settled status with both confirmation and proof of their status in digital-only form.Footnote 14 When status is granted, applicants are notified by an automatically generated email notification. This message itself is not proof of status but only a notification. Proof of status can only be accessed online. In principle, a person can access their status anywhere (if they have the technology and internet) and at any time by logging into the relevant government webpage.Footnote 15 Individuals can also share their status with others who may need to see it, including employers and landlords. For EEA nationals, the EUSS is strictly digital-only; nobody receives an alternative form of status. As the Home Office puts it, digital status means that ‘[e]vidence of… status will be given to EU citizens in digital form; no physical document will be issued to them. They will control who they wish to share this with’.Footnote 16 By 31 March 2021, 4,689,660 EEA nationals held settled or pre-settled status and were thus within the digital-only status policy. This represented approximately 6.9% of the UK population at the time.

While the EUSS is the most prominent and largest deployment of digital status to date, it is clear that government strategy is to rely on this mode of status much more widely in the future. Policy statements around the replacement of EU free movement rules have made this clear. The Government's White Paper on The UK's future skills-based immigration system stated that:

Online status checking services will continue to be developed to allow individuals to share their status with employers, landlords and other service providers who have legal responsibility for confirming an individual's status. This approach will remove the current reliance on individuals having to produce documentary evidence of their status, or service providers having to interpret a myriad of documents.Footnote 17

Baroness Williams, a Home Office Minister, recently confirmed this long-term intention to Parliament:

Moving to online services is part of our declared aim of moving to a system which is digital by default, whereby all migrants, not just EEA citizens, will have online access to their immigration status, rather than having physical proof.Footnote 18

This planned expansion of the use of digital status is part of a package of data infrastructure development in immigration administration. The design of the EUSS is the forerunner in this respect; digital-only status is just one part of a wider digital design.Footnote 19 Under the EUSS system, applications for settled or pre-settled status are made online and then processed through an automated decision-making system built on extensive data-sharing arrangements between the Home Office, the Department for Work and Pensions, and HM Revenue & Customs. This strategy also requires more extensive data linkage across departments and other actors, through which digital status is expected to facilitate ‘[r]eal time verification of status [that] will give other government departments and delivery partners, including employers and landlords, the tools to establish genuine, lawful, residence and rights’.Footnote 20 Digital status, for those who hold it, will be an essential pass through an increasingly digitalised landscape of public services.

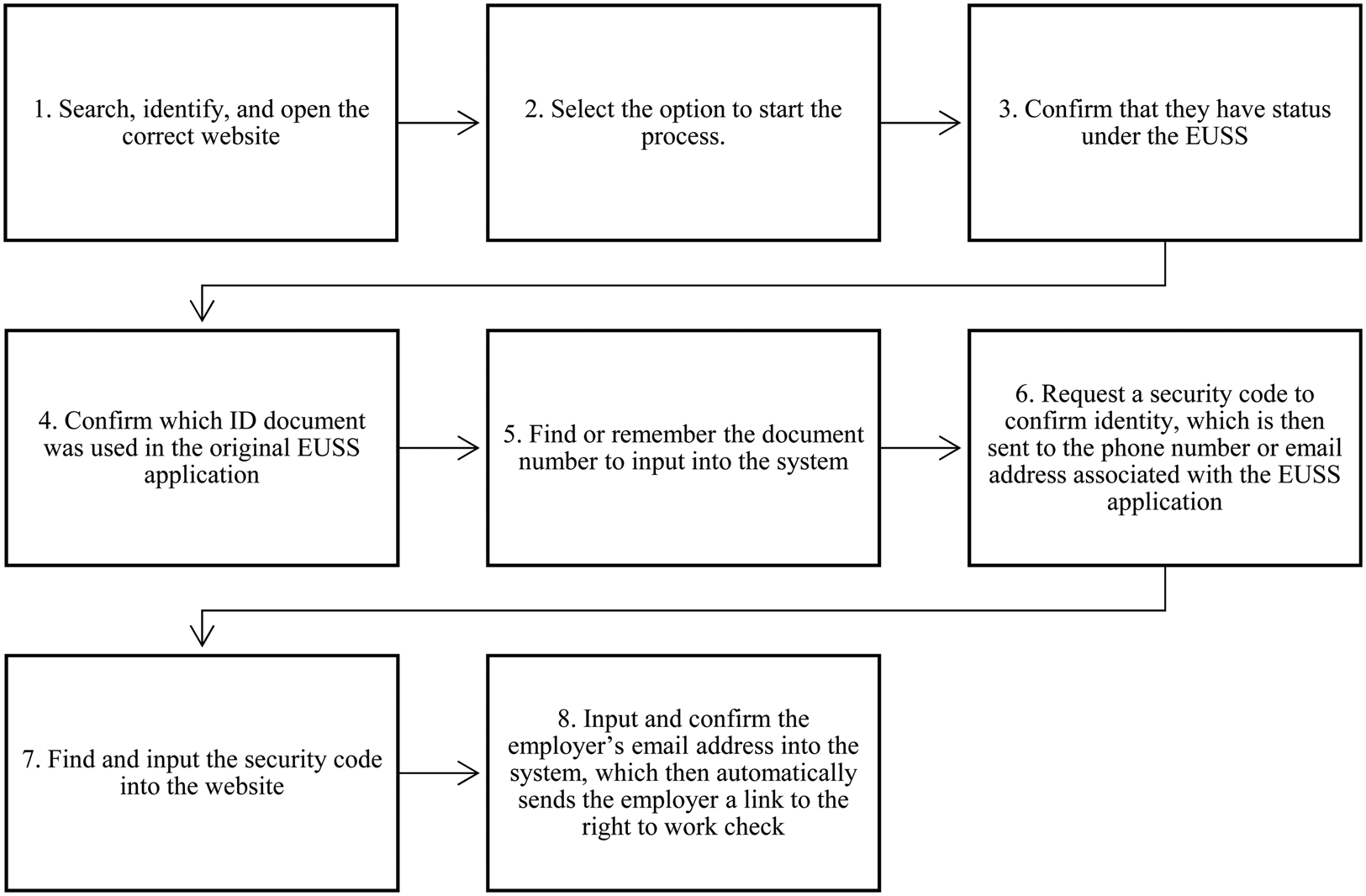

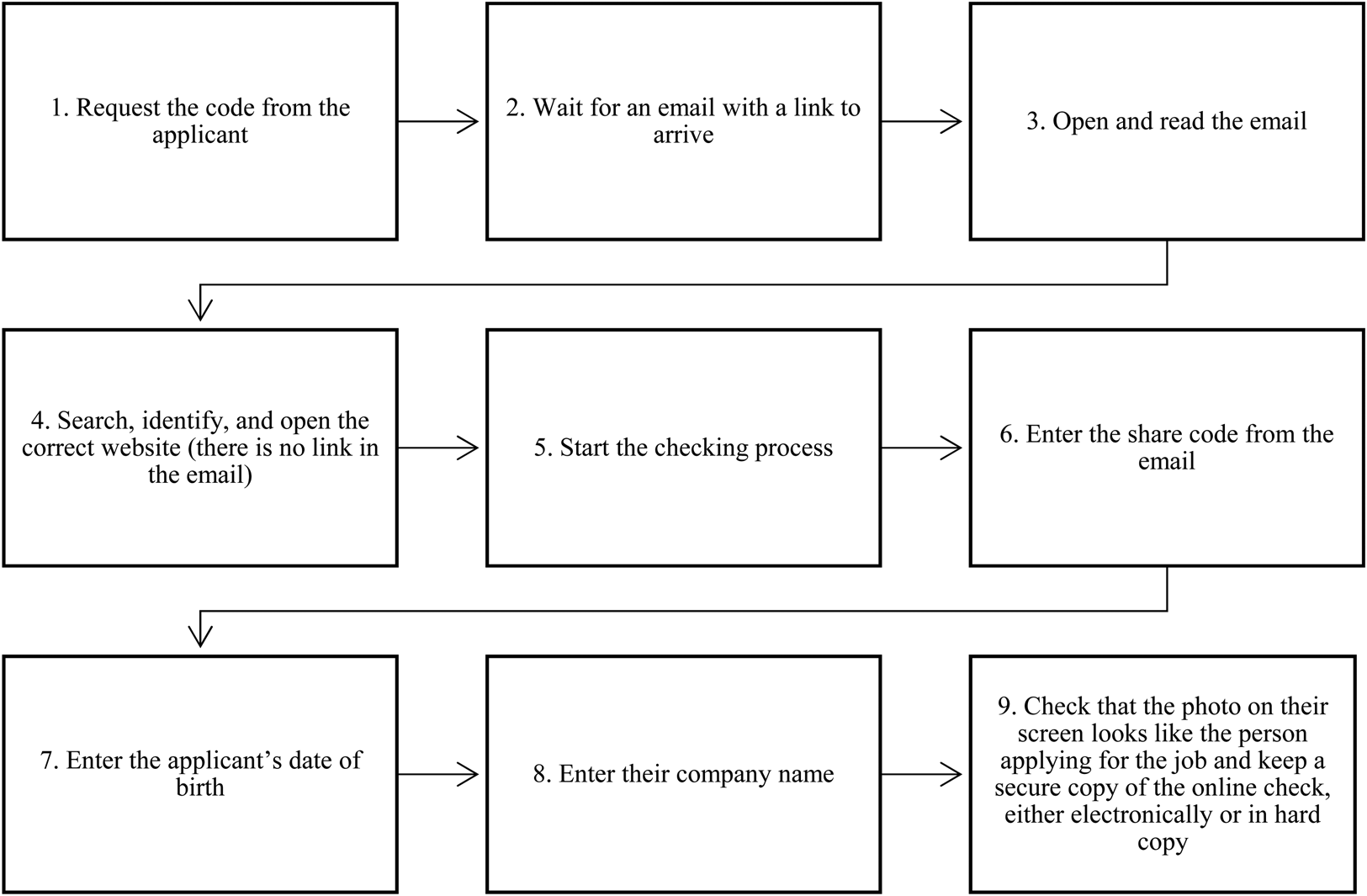

Digital-only status is routinely practically significant to individuals who rely on it because people need to prove their immigration status not only to enter or leave the UK, but also to rent a house, find a job, open a bank account, or access healthcare and social security. The ‘hostile environment’ policy, now referred to by the government as the ‘compliant environment,’ also requires a range of third parties – landlords, employers, bankers, healthcare workers, police and other public officials – to check the immigration status of people they engage with.Footnote 21 Such checks are already in operation and proving controversial,Footnote 22 and digital-only status further significantly changes how people access and prove their status and thus changes the dynamics of these interactions. In practical terms, when asked to prove their entitlement to reside in the UK, people reliant on digital status have to take a series of steps. By way of example, Figure 1 sets out the steps required of a holder of digital-only status when proving their status for the purpose of a new job. Figure 2 sets out the actions required of the employer in the same situation. It is important for us to illustrate what these steps are in granular detail because, as we show in the next part of this paper, the mechanics of the process contribute to the overall discriminatory effects of the policy.

Figure 1. Steps required of digital status holder to prove status for the purposes of employment

Figure 2. Steps required of an employer to established proof of status for a potential employee

2. Indirectly discriminatory effects

In the context of the EUSS, digital-only status has been adopted as a blanket policy. From the time of its original policy statement on the EUSS in June 2018, the Home Office has maintained this position.Footnote 23 To be clear, this is a policy choice: no law expressly requires the UK Government to provide digital-only status under the EUSS.Footnote 24 There have been numerous warnings about the various risks inherent in this choice and the need for a more flexible approach.Footnote 25 Yet, the policy has been maintained for all EEA and Swiss nationals granted status under the EUSS, irrespective of whether they have protected characteristics or might face difficulties in accessing or using digital status.

The Home Office claims that the digital-only status policy positively benefits vulnerable groups.Footnote 26 One such claim is that some vulnerable groups, such as the elderly, are rarely required to prove their status and maintaining paper documents thus presents ‘an additional level of bureaucracy’ for them.Footnote 27 Another example relied on is that visually impaired and dyslexic people may have difficulties reading a physical document.Footnote 28 It is clear that digitalisation has the potential to help some individuals, including vulnerable individuals, better engage with public services.Footnote 29 However, it is also clear that the policy has the potential to seriously disadvantage people and groups who are digitally excluded, and ultimately frustrate their rights and entitlements under law.

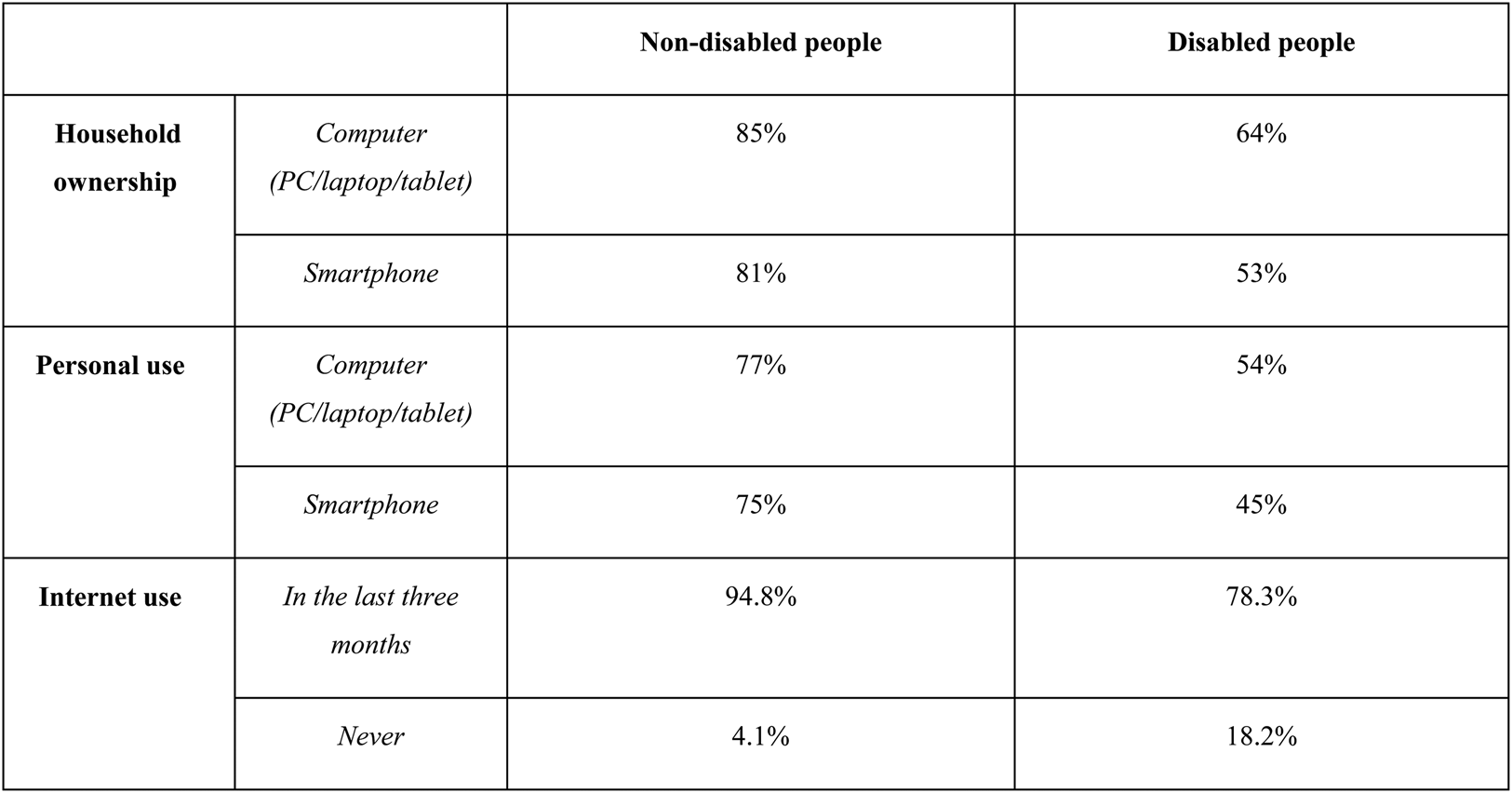

We focus on three groups of EU citizens: disabled people, older people, and Gypsy, Roma and Traveller people.Footnote 30 To show how digital-only status disproportionately affects these groups, we begin with the available statistical evidence. Statistics are often used in indirect discrimination claims to establish that a provision, criterion or practice has a disparate impact on a particular group.Footnote 31 In relation to disabled people, statistical evidence from the Office of National Statistics (ONS) and the Office for Communications (Ofcom) shows that they are less likely to have the hardware and digital literacy required to access and use digital status, as compared to the general public. Figure 3 summarises this statistical evidenceFootnote 32.

Figure 3. Statistical evidence for the digital exclusion of disabled people

The statistical evidence available pertaining to older people is to similar effect. According to ONS and Ofcom, older people are less likely to have a household internet connection,Footnote 33 to have access to or use a computer or tablet,Footnote 34 to use a smartphone,Footnote 35 or to use the internet,Footnote 36 as compared to the general public. In general, as people become older, these disparities become larger.Footnote 37

Regrettably, there is a lack of consistent data collection on Gypsy, Roma and Traveller people in general.Footnote 38 This means that evidence on their digital exclusion is limited. But the available evidence strongly suggests that these communities are seriously digitally excluded. Recent studies by grassroots organisations show that these groups are much less likely to have household internet connections, to have access to a computer, smartphone or tablet, to use the internet, or to feel confident performing tasks using digital technology, as compared to the general public.Footnote 39 These communities are also seriously marginalised in ways which are independently correlated with digital exclusion (eg lack of access to education, low incomes, and low literacy levels).Footnote 40

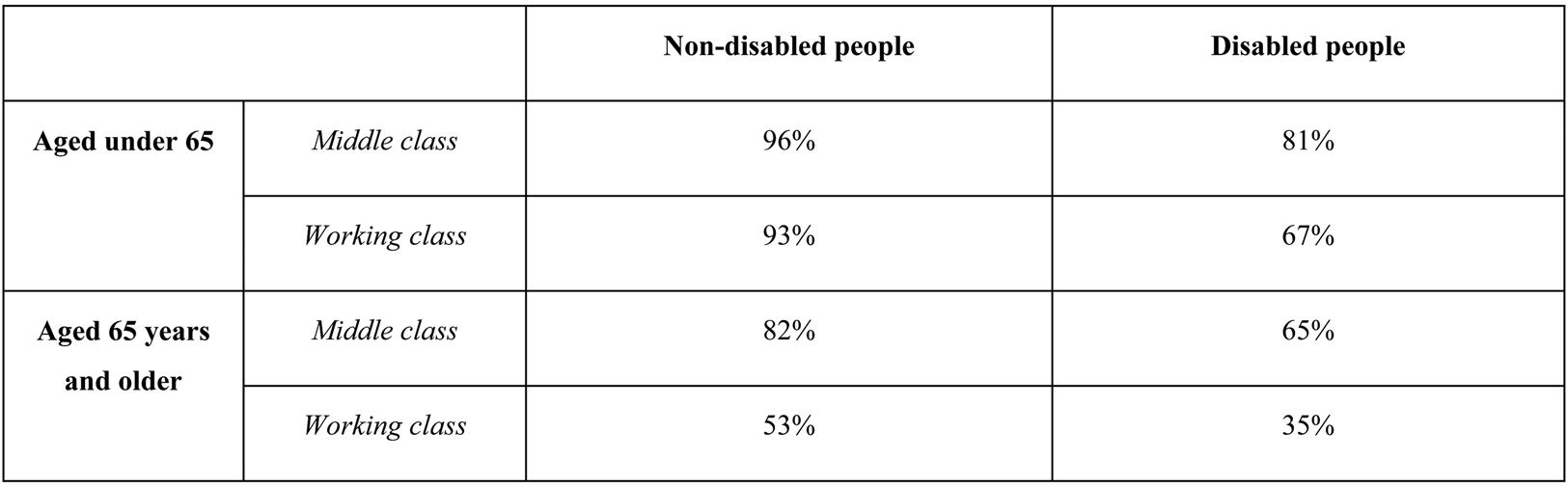

Digital exclusion, like other kinds of disadvantage, is intersectional.Footnote 41 The overlap and interaction between a person's different characteristics can influence how and to what extent they experience digital exclusion. For example, Figure 4 shows how age, disability and socio-economic status intersect in relation to internet use in the UK.Footnote 42 It is important to keep this variation in mind when considering how digital-only status affects different people within particular groups, and whether the Government's mitigations might address some vectors of digital exclusion but not others.

Figure 4. Internet use by age, disability and socioeconomic status

To summarise this statistical evidence, and to illustrate how people in these groups will face difficulties with digital status in practice, we have constructed three composite profiles.Footnote 43 The profiles are not intended to suggest that the people in these groups are homogenous. Rather, they are intended to encapsulate the statistical evidence on the comparative digital exclusion faced by these groups, and to highlight how digital-only status will disproportionately disadvantage these groups. We set out the three composite profiles below:

P is 28 years old. He has a visual impairment. He can read words printed on paper if the letters are not too small, but electronic screens appear blurred. As a consequence, P has never owned a computer. He has a landline phone and a basic mobile phone, but not a smartphone. He has never learned how to use the internet. With the assistance of his local Citizens Advice Bureau, P applied for and obtained settled status in July 2019.

B is 70 years old. She has never been particularly interested in modern technology. She feels like she manages perfectly well without it and she is a bit worried about the risk of being scammed. B has never bothered to get an internet connection at her flat. She does not own a computer, and she has a basic mobile phone for calling people in emergencies, but not a smartphone. She has barely used the internet in her life. B's niece helped her set up an email account some years ago, and a friend helped her to apply for and obtain settled status under the EUSS in February 2020, but she has not used the internet since then.

L is 39 years old. She is Roma. Her family does not have a household internet connection or own a computer. L has a smartphone, but she mainly uses it for phone calls and for basic social media every week or so. She does not otherwise use the internet and, in any case, the internet connection where she lives is often patchy. L generally does not like using technology to do things, as she finds she needs assistance to complete even simple tasks. With the assistance of a support group, L created an email address and obtained settled status in November 2019. She has not used her email address or accessed her status since then.

P, B and L face at least three obstacles to accessing and using their digital status.Footnote 44 The first obstacle is a lack of access to internet infrastructure. While P and B could obtain an internet connection if they wished to, L struggles to get a reliable internet connection at all, because of where she lives. The second obstacle is a lack of access to the hardware required to access the internet. P and B own neither a computer nor a smartphone, and L does not own a computer. Another obstacle is a lack of digital literacy: the skills required to use digital technologies and the internet.Footnote 45 P, B and L have low digital literacy. They have little to no experience of using the internet to perform the range of tasks required to maintain and use their digital status. As discussed above, those tasks include finding the correct website, navigating that website successfully, managing multiple media to identify and enter the correct information into the website (ie the ID document and the employer's email address), and completing a two-factor authentication process using a separate technology (ie a mobile phone or email address).

To demonstrate the impact of these obstacles in practice, it is useful to consider the following situations in which P, B and L might need to use their digital status:

P has applied for a job. The employer calls P to arrange a time for an interview, and asks him to ‘bring along documents for the right to work check’. P brings his passport and letter of confirmation of status to the interview, but the employer says that he needs a ‘code’ from him. P does not have a smartphone with which to access his status. The employer offers to let him use one of its computers, but this is no assistance. P cannot remember the ID document or email address associated with his EUSS application and he does not know how to find and navigate the website. P misses out on the job.

B needs to find a new flat. She inspects one which she likes and she makes an offer to the real estate agent. The agent says that, before he gives B the flat, he has to check whether she is allowed to be in the UK.Footnote 46 The agent asks her to go to a website and send him a link to check her status. B is confused. She remembers applying to the EUSS, but she doesn't understand what the landlord wants her to do. Several other people are interested in the flat, and the agent gives it to someone else before B can work out what to do.

L wants to apply to her local authority for council housing. The application form requires L to provide evidence of her immigration status, so that the authority can determine whether she is eligible. Although L has a smartphone, she does not know how to use it to show her status, and she also cannot remember the details for the email address she created when she applied to the EUSS. L includes her passport details in the application, but because she has not provided proof of her status, her application is rejected.

These examples illustrate how the Home Office's policy of providing digital-only proof of status puts P, B and L at a particular disadvantage when compared to EU citizens who do not share their protected characteristics: disability, age, and race, respectively.Footnote 47 The primary disadvantage is that P, B and L cannot prove their status. P, B and L also suffer secondary disadvantages because of their inability to prove their status: exposure to potential lost benefits (eg medical treatment or housing) or additional burdens (eg upfront charges or administrative removal) and the distress caused by that exposure. EU citizens without P, B, and L's protected characteristics are more likely to be able to prove their status, because they are, statistically speaking, more likely to have access to internet infrastructure and the necessary hardware, and to have the requisite digital literacy. Consequently, they are less likely to be exposed to the disadvantages suffered by P, B and L.

P, B and L are composite profiles. Some people who share their protected characteristics will have no trouble accessing and using their status. And some people without their protected characteristics will, for whatever reason, suffer the same disadvantages. But this does not undermine our claim that digital-only status is indirectly discriminatory. As Lady Hale noted in Essop v Home Office, ‘there is no requirement that the [policy] put every member of the group sharing the particular protected characteristic at a disadvantage’ compared to every person without that characteristic.Footnote 48 What is required is that the proportion of disabled people, older people or people from Gypsy, Roma and Traveller communities who cannot prove their status is larger than the proportion of people without those characteristics.Footnote 49 This is established by the statistical evidence. Once that evidence is accepted, it ‘inevitably follows’ that digital-only status gives rise to indirect discrimination.Footnote 50

Our analysis, articulated through the use of composite profiles, is consistent with the Government's own analysis of similar digital status systems. In March 2018, the Government Digital Service (GDS) assessed the Home Office's ‘Prove your right to work’ service – an online system for people to prove their right to work in the UK. GDS noted that the Home Office had ‘very strong evidence’ that any move from physical proof of status to ‘digital only services’ would ‘cause low digital users a lot of issues’.Footnote 51 It concluded that there was ‘a clearly identified user need for the physical card at present, and without strong evidence that this need can be mitigated for vulnerable, low-digital skill users, it should be retained’.Footnote 52 This conclusion applies with equal force to the use of digital-only status in the EUSS.

Our analysis is also supported by the important decision in LH Bishop Electrical Co Ltd v HM Revenue and Customs, a successful challenge to digital discrimination in another area of public administration.Footnote 53 In 2010, HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) made regulations requiring businesses to file their value added tax returns online, subject to limited exemptions.Footnote 54 In Bishop Electrical, the First-tier Tribunal (Tax Chamber) found that the regulations indirectly discriminated against people on the basis of age, disability and remote location, and thus violated Article 14 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR).Footnote 55 The Tribunal accepted statistical evidence that older people, disabled people and those living remotely – like the appellants before it – were less likely to own or know how to use a computer, or to have access to the internet.Footnote 56 It was therefore more difficult for these groups to comply with the obligation to file returns online.Footnote 57 And, as we discuss further below, the Tribunal rejected HMRC's ostensible justifications for this discrimination.Footnote 58 In response to the decision, HMRC amended the regulations to enable people to make a paper or telephone return if an electronic return was not ‘reasonably practicable’.Footnote 59

Where a public authority's apparently neutral policy disadvantages a protected group, as we argue is the case with digital-only status, there are two avenues through which it can still be considered lawful.Footnote 60 The public authority can take steps to eliminate the disadvantage suffered by the protected group, by adjusting the policy or providing additional assistance to members of the group. Or the public authority can show how, notwithstanding that disadvantage, the policy is justified, because it is a proportionate means of achieving a legitimate aim. The next two parts of this paper show that, in the case of digital-only status, these approaches have been unsuccessful to this point. The Home Office has neither eliminated nor adequately justified the indirectly discriminatory effects of the policy.

3. Has the discrimination been eliminated?

In the context of the EUSS, the Home Office has acknowledged that digital-only status may disadvantage people ‘who may find it harder to use digital services because they are not regular internet users’.Footnote 61 However, it argues that it has taken steps to limit the impact of this disadvantage.Footnote 62 Before we show why the steps taken are an unconvincing response to the discriminatory impacts, two important points must be made about this analysis. First, to refute a claim of indirect discrimination, a defendant's mitigations must ‘eliminate’ the disadvantage suffered by the protected group.Footnote 63 As Lewison LJ noted in R (Ward) v London Borough of Hillingdon:

[T]he key principle is that the goal is equality of outcome. If a [policy] results in a relative disadvantage as regards one protected group, any measure relied on as a “safety valve” must overcome that relative disadvantage. Put simply, if the scales are tilted in one direction, adding an equal weight to each side of the scales does not eliminate the tilt.Footnote 64

It is not sufficient that any measures merely go some way to alleviating that disadvantage.Footnote 65 Secondly, the public authority bears the burden of proof in this regard. It must adduce evidence establishing that its mitigations have actually eliminated the disadvantage to the protected group.Footnote 66 If that evidence is absent, equivocal or unconvincing, the defendant's mitigations will be assumed not to have addressed the disadvantage.

The Home Office claims to have taken four steps to eliminate the disadvantage caused by digital-only status in the context of the EUSS. First, it has allowed EU citizens to continue to use their passport or national ID card to prove their immigration status until 30 June 2021.Footnote 67 This is said to give EU citizens ‘time to get used to transitioning from using physical documents to accessing and sharing their immigration status information online’.Footnote 68 But this six-month ‘grace period’ after the end of the transition period does nothing to address the disadvantages discussed above.Footnote 69 It is not realistic to suggest that, within a matter of months, individuals in circumstances akin to P, B and L will be able to acquire the requisite hardware, skills, and confidence to access and use their digital status.

Secondly, the Home Office claims that it already provides successful EUSS applicants with physical notice of their leave to remain in the UK. During a House of Lords debate on digital-only status, Baroness Williams of Trafford, Minister of State for the Home Department, put this point in the following terms:

I would like to reassure noble Lords that we already provide people who are granted settled or pre-settled status with a formal written notification of their leave. It is sent in the form of a letter, by post, or a PDF, by email, and sets out their immigration status in the UK. They can retain the letter, or print it, or electronically store the PDF and keep it as confirmation of their status for their own records and use it if they wish when contacting the Home Office about their status.Footnote 70

Baroness Williams asserted that these confirmation letters ‘should reassure individuals about their status when dealing with the Home Office in the future’.Footnote 71 But a confirmation letter is not and cannot be accepted as proof of immigration status.Footnote 72 As Lord Paddick noted in the same debate:

The Government have said, time and again, that, as proof of the recipient's immigration status, these letters are not worth the paper they are printed on. It is disingenuous of the Minister to pray in aid these letters in answer to these amendments [providing for the issue of physical proof of status under the EUSS].Footnote 73

In short, the issuing of unofficial confirmation letters goes no meaningful distance to address the disadvantages caused by digital-only proof of residence.

Thirdly, the Home Office has designed the webpage for accessing and proving status in accordance with government accessibility requirements.Footnote 74 The Home Office's accessibility statement for the webpage notes that it wants ‘as many people as possible to be able to use this website’.Footnote 75 To achieve this, the web design has incorporated certain features, including that that users can: change colours, contrast levels, and fonts; zoom in up to 300% without the text spilling off the screen; navigate most of the service using just a keyboard; navigate most of the service using speech recognition software; and listen to most of the service using a screen reader. Inclusive design of digital public services is essential to their success. It plays a vital role in addressing the difficulties which those services present for people who are digitally excluded, and any efforts in this regard ought to be welcomed. But inclusive design ‘may nonetheless be insufficient to address some of the more complex issues of digital divide’.Footnote 76 The circumstances of P, B and L demonstrate this point. The inclusive design of the relevant webpage does not address the essential problem with digital-only status in their circumstances: lack of the resources and skills necessary to access the webpage in the first place.

Finally, the Home Office argues that it has created or funded services to support people in accessing and proving their status.Footnote 77 It has established the Settlement Resolution Centre to assist people who are applying to the EUSS or accessing their status.Footnote 78 It has also funded 72 community organisations across the UK to support vulnerable people in applying to the EUSS.Footnote 79 Finally, it has engaged ‘We Are Digital’, a private digital training provider, to provide an ‘Assisted Digital’ service for EUSS applicants.Footnote 80 There are, however, multiple problems with seeking reassurance in these measures.

The first problem is that it is unclear whether and for how long these services will actually be available for people struggling to access their status. At present, the Home Office has only funded the 72 community organisations to help people apply to the EUSS, and not to help people access and prove their status into the future.Footnote 81 Their current funding expires at the end of September 2021.Footnote 82 The same appears to be true of the Assisted Digital services provided.Footnote 83 This would leave the Settlement Resolution Centre as the only support for people disadvantaged by digital-only status after the end of the ‘grace period’ on 30 June 2021, if it remains open.

The second problem is that these support services may be inaccessible to the very people who are disadvantaged by digital-only status. For example, the Settlement Resolution Centre can be contacted via telephone or an online form.Footnote 84 The telephone number is listed on a government webpage, but it is unclear how people who are digitally excluded are to find this information.Footnote 85 The online form is, by definition, inaccessible to such people.Footnote 86 Another potential barrier is cost. Calls to the Settlement Resolution Centre cost up to 10p per minute from landlines and up to 40p per minute from mobile phones.Footnote 87 After inspecting the Government's arrangements for the applications to the EUSS, the Independent Chief Inspector for Borders and Immigration noted that these charges ‘could act as a deterrent to those most in need of help to apply’.Footnote 88 This concern applies with even greater force in relation to people accessing and proving their status. In the hostile environment, such people will repeatedly be required to prove their status, and thus will repeatedly have to incur the cost of contacting the Settlement Resolution Centre for assistance.

The third problem is that these support services may be unable to meaningfully assist people who are digitally excluded. Consider B, the 70-year-old woman in the process of finding a new flat. Even if B managed to find out about the Settlement Resolution Centre, locate its phone number, and speak to a member of staff (when they are available), she would still face significant hurdles in proving her status. The official would need to ask B to find and travel to a publicly accessible computer (eg in a public library), because B does not have a computer or smartphone. The official would then need to guide B through the process of proving her status, notwithstanding that B has barely used a computer or the internet in her life. This process would also have to be completed very quickly. In a competitive rental market, properties are often let the same day they are advertised, so any delay would risk B losing the flat.Footnote 89 And this process would have to be completed every time B had to prove her status in the hostile environment: opening a bank account, renting a property, accessing healthcare, and so on. It is not credible to claim that these support services eliminate the disadvantages caused by digital-only status.

The Home Office has said that it is exploring additional steps to address some of the deficiencies we have identified.Footnote 90 For example, the Home Office is ‘developing’ automated, system-to-system checks with other departments and the NHS, so that EU citizens will be able to access public services without personally having to prove their status.Footnote 91 These automated checks are yet to materialise and, even once they are in place, they would not assist people with proving their status to private parties, such as employers, landlords, and banks. In her review of the Windrush scandal, Wendy Williams concluded that the Home Office had been ‘overly optimistic’ about ‘the effectiveness of the proposed “mitigations”’ for its hostile environment policy.Footnote 92 Recent history appears to be repeating itself in this respect too. At the very least, the Home Office is yet to present a shred of convincing evidence that the steps it has taken go close to eliminating the disadvantages caused by digital-only status.

4. Unconvincing justifications

This part of the paper turns to address the question of whether digital-only status, as operated within the EUSS, can still be justified as a proportionate means of pursuing a legitimate aim. The central questions on the issue of proportionality are those set out by Lord Reed in Bank Mellat:

(1) whether the objective of the measure is sufficiently important to justify the limitation of a protected right, (2) whether the measure is rationally connected to the objective, (3) whether a less intrusive measure could have been used without unacceptably compromising the achievement of the objective, and (4) whether, balancing the severity of the measure's effects on the rights of the persons to whom it applies against the importance of the objective, to the extent that the measure will contribute to its achievement, the former outweighs the latter … In essence, the question at step four is whether the impact of the rights infringement is disproportionate to the likely benefit of the impugned measure.Footnote 93

We argue that digital-only status is not a proportionate means of achieving any of the Home Office's apparent objectives. First, we examine the range of objectives behind the policy, showing that they rest on problematic assumptions.Footnote 94 Secondly, we propose less intrusive measures that would not unacceptably compromise the achievement of the policy's objectives. Finally, we argue that the Home Office has failed to strike a fair balance between those policy objectives and the rights of people disadvantaged by digital-only status in the ways discussed above.

(a) The objectives of digital-only status

There are three primary objectives behind the digital-only status policy: increasing convenience for holders of status and third parties, reducing costs for the Government, and enhancing the security of immigration status.Footnote 95 Similar objectives have been advanced to justify the discriminatory or perverse effects of digital systems in other areas of government.Footnote 96 Before examining these objectives in detail, however, it is important to note that they all connect to a more general, underlying objective: enforcing immigration and border controls. The promise of digital-only status is that it will enable the UK to control its borders and manage immigration more conveniently, more cheaply and more securely. Expressed at that level of generality, this is a legitimate aim for the Government to pursue. However, it cannot be said to be proportionate to implement a policy in the pursuit of enforcing immigration law and policy that has the effect of disconnecting people from their proof of lawful residence. In this way, digital-only status undermines the very aim which is said to justify it. The courts have also recognised that there is no rational connection between the state's interest in immigration control and discriminatory treatment of various groups with protected characteristics.Footnote 97

The first objective of digital-only status is to increase convenience for holders of status and the third parties required to check status. Holders of status ‘will be able to view, understand and update their information from a single place’, and ‘will not have to resubmit information or prove things again in subsequent applications where there has been no change’.Footnote 98 In this way, digital-only status allows the Home Office to generate ‘customer intimacy’ by offering a more personalised service that is easier to access and use.Footnote 99 It is also intended to reduce errors in proving status by reducing ‘piecemeal interactions, services and paper products’ which should make it ‘easier for users to transact with… services in a streamlined, seamless way’.Footnote 100 From the perspective of third parties, they should ‘see only the information that is relevant and proportionate to their need’.Footnote 101 This should ‘remov[e] the need for employers, and others, to authenticate the myriad different physical documents and interpret complex legal terminology or confusing abbreviations’.Footnote 102 The outcome of the switch to digital status, on this reasoning, should be that it is more convenient for all involved to share and check status.Footnote 103

It is clearly legitimate for the Government to make proving immigration status more convenient. But it is essential to examine whether digital-only status will actually achieve this objective, and which people will enjoy these benefits in practice. Putting to one side the problems of digital exclusion discussed above, it is not obvious that digital immigration checks will generally be more convenient for status-holders and third parties. There is already evidence that third parties are unwilling to undertake the checks required under the hostile environment. In January 2020, the Court of Appeal found that the right to rent scheme caused indirect discrimination, although the discrimination was justified as a proportionate means of deterring irregular immigration.Footnote 104 The Court accepted evidence that landlords were less likely to rent to those without British passports, those with complicated immigration status, and people with ‘foreign accents or names’ as a result of the scheme, due to administrative convenience and a fear of the consequences of letting to an irregular immigrant. Quite simply, landlords felt they were ‘forced to discriminate against certain groups, rather than face the possibility of a fine’.Footnote 105 The research underpinning the case, conducted by the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants (JCWI), also found that the majority (65%) of landlords would not rent to someone who needed time to provide documentation, an ‘attitude which will affect anyone applying for a tenancy who lacks clear documents or does not have documents, such as a passport, to hand’.Footnote 106 When landlords were presented with a potential tenant who required the use of an ‘online checking tool’ (which requires landlords to request information about a tenant's immigration status from the Home Office and takes 48 hours to receive a response), 85% of them did not respond. Only 3.3% of the landlords contacted by this tenant responded and invited further interaction.Footnote 107

The online checking procedure for digital status, described above, can be time-consuming, particularly for those unfamiliar with it. The reluctance of landlords captured in the JCWI research may be exacerbated by a lack of physical proof of status or if they find it ‘too complicated or troublesome to engage with electronic systems’.Footnote 108 Similar concerns have been raised about employers and the prospect that they may choose to hire or retain someone with more familiar status documents. Ultimately, as the Home Affairs Committee observed:

[T]his system risks being confusing, increases the workload on employers and landlords, relies on their goodwill and engagement with this new and unfamiliar process, requires individuals and employers to have the necessary electronic hardware, and could result in individuals not employing or renting to someone due to the confusion and difficulties involved in proving status.Footnote 109

Far from being convenient for holders of status, digital-only status could lead to difficulty, and even discrimination, when seeking to access homes, jobs, and services. The Exiting the EU Committee observed the potential further risk of exploitation if someone ‘cannot persuade an employer or landlord of their status’.Footnote 110 As discussed above, it is also questionable whether a short transition window where paper documents can still be used – as adopted in the context of EUSS – eliminates these risks.Footnote 111 These doubts about the supposed benefits of digital status seem to be reflected in the attitudes of EU citizens in general. In January 2020, a survey of over 3,000 EU citizens found that 89% were unhappy with the lack of physical proof of status under the EUSS.Footnote 112

The convenience of digital-only status also rests heavily on the performance of the underlying technology. There have already been many reported technical errors, including where an individual trying to access the right-to-work scheme faced the error message stating ‘we can't show your record’.Footnote 113 Technical errors would leave people ‘in limbo, unable to assert their rights’.Footnote 114 Other digital errors could also erode trust in the system. For instance, there have already been a significant number of data breaches in the EUSS.Footnote 115

Finally, it is important to note, as we did above, that various holders of status will not enjoy the convenience of digital-only status. For people who are digitally excluded, digital-only status not only offers no convenience, but risks disconnecting them from proof of their lawful entitlement to reside in the UK. As we discuss further below, the benefits and burdens under the digital-only status policy are unfairly distributed. Even accepting the importance of the objective of improving convenience, it cannot justify a blanket policy which risks disconnecting lawful residents from proof of their status.

The second objective of digital-only status is to reduce costs for the Government.Footnote 116 For the Government, a digital-only system will be significantly cheaper than a paper-based system. Since 2008, the Home Office has issued one million residence cards.Footnote 117 A paper-based system for the EUSS would require over four million additional residence cards for applicants, plus additional cards for replacements and changes of status. The Government has estimated that issuing these cards would cost between £28 and £75 per person.Footnote 118 In debates in the House of Lords, Baroness Williams argued that a paper-based system for the EUSS ‘would incur a significant and unfunded cost’ and ‘divert investment away from developing the digital services and support for migrants using those services that we need for the future’.Footnote 119 Under the Withdrawal Agreement, the UK could charge EU citizens for at least some of this cost, but only up to the amount that it charges UK nationals for issuing similar documents.Footnote 120

There are several problems with the cost objective. First, as a matter of law, there is some doubt over whether cost savings can justify indirect discrimination. As Lord Hope and Lady Hale said in O'Brien v Ministry of Justice:

Of course there is not a bottomless fund of public money available. Of course we are currently living in very difficult times. But the fundamental principles of equal treatment cannot depend upon how much money happens to be available in the public coffers at any one particular time or upon how the State chooses to allocate the funds available between the various responsibilities it undertakes.Footnote 121

Some lower court and tribunal decisions draw a distinction between the goal of cost savings alone, which cannot justify discriminatory effects, and cost savings as one among several goals, which together can justify such effects.Footnote 122 Other decisions draw another distinction between governments, which cannot use cost savings as a justification at all, and employers, which can use cost savings as one among several justifications.Footnote 123 These distinctions are not without difficulty.Footnote 124 Whatever the precise position, the authorities suggest that the courts are slow to accept cost savings as justifying a discriminatory government policy.

Secondly, digital-only status does not reduce costs so much as shift them. It places the burden on status holders and third parties to be in a position to use digital status: to have access to the requisite internet infrastructure and hardware, and to have the requisite digital literacy. Many people will have to incur substantial costs to do so. A similar issue arose in Bishop Electrical. The purpose of making online tax filing mandatory was ‘to save HMRC costs in collecting taxes’: about £32 per person per year.Footnote 125 But the policy would compel people who did not own or know how to use a computer to spend up to £400 per year to be in a position to file their returns online.Footnote 126 The First-tier Tribunal found that these additional costs ‘would be out of all proportion to the cost benefit to HMRC’.Footnote 127 This disproportionate cost-shifting, in combination with several other factors, meant that HMRC's cost savings did not justify the discriminatory effects of mandatory online filing.Footnote 128

A similar argument could be made about digital-only status in the context of the EUSS. The Government says that a digital-only system will save it a one-off cost of £28 and £75 per person, together with some additional costs for replacements and changes of status.Footnote 129 But people who are digitally excluded may have to incur larger and ongoing costs to use digital status. In 2020, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and Loughborough University estimated that, to reach a minimum acceptable standard of living, an adult in the UK would need to spend about £380 per year on digital technologies and the internet.Footnote 130 In other words, from the perspective of a person who is digitally excluded, digital-only status may impose costs which are disproportionate to the expected savings for the Government. For these reasons, we suggest that the cost objective provides, at best, a weak justification for digital-only status.

The third objective of digital-only status is to improve the security of immigration status. Physical documents, so the reasoning goes, are at risk of being lost, stolen or damaged, and digital status, suspended in the cloud, is insulated from such earthly risks.Footnote 131 There is a basis for these security concerns. For example, there have been cases where paper documents have been controlled by others, including in cases of domestic violence, modern slavery, and human trafficking.Footnote 132 In such circumstances, it is possible to imagine digital status giving status-holders firmer possession of their proof of residence. Similarly, it is plausible that the enhanced security of the digital code system may reduce the possibility of forgery and fraud.Footnote 133 That being said, the evidence for these claims is limited.

On the other hand, there is emerging evidence that digital status generates new security risks. For instance, there have been reports of ‘advice sharks’ making applications on behalf of others, charging for this service (when the application is free), and then retaining access through email addresses and phone numbers to charge individuals further for access to their status.Footnote 134 The EU Justice Sub-Committee also raised concerns that digital-only proof could be used by people traffickers and illegal gangmasters to exert control over their victims.Footnote 135 Digital status may be more secure for some people, but it remains vulnerable to the same problems as physical status and potentially opens up new routes for exploitation. For example, if a perpetrator was in control of a person's initial application (and therefore the phone number and email address associated with it, to which the security code is sent), they would have control over who could access the person's status.

The security objective may also be undermined by less sinister but equally problematic practical issues. For instance, evidence suggests that some applicants lack an email address to receive their status. This has resulted in advisors ‘setting up email addresses for people and maintaining a record of log-in details in-house as a backup for individuals’.Footnote 136 Such a fix – which may seem an appropriate immediate solution – ultimately leaves a person disconnected from their status and places control with a third party, with all the risks that entails. Even people with access to email and other relevant technology can be disconnected from their status if their details are not kept up to date.

Digital status also creates new, systemic security risks. If a person's physical proof of status is lost or stolen, the consequences, while very serious, are at least limited to that person. If the Government's digital status systems are compromised, either carelessly or maliciously, this could jeopardise the status of thousands or even millions of EU citizens. Other countries have experienced significant data breaches in large identity databases. In India, for example, the personal information of more than a billion Indian people leaked from the Government's Aadhaar database in 2018.Footnote 137 Nor is the Home Office immune from such problems. In February 2021, for example, the Home Office admitted that offence records for 112,000 people had been inadvertently deleted from the Police National Computer, due to a ‘coding mistake’.Footnote 138 A similar mistake with digital status would be potentially disastrous.

Security is, again, a legitimate objective of a policy. But the early evidence shows that digital status, like physical documentation, can still be lost, stolen, or manipulated in a variety of ways. Moreover, as we discuss further below, the security objective does not justify the adoption of a policy which has discriminatory impacts and risks disconnecting people from their proof of lawful residence.

(b) Less intrusive alternatives

Our analysis is that the three main objectives of digital-only status – convenience, cost and security – rest on problematic assumptions. We now turn to whether less intrusive measures could be used without unacceptably compromising the achievement of those objectives. Ultimately, it is for the Government to devise a functioning and lawful scheme for proof of immigration status.Footnote 139 We do not attempt to devise any such scheme here. But in general terms, there is an obvious, less intrusive alternative to digital-only status: providing physical proof of status as a complement to digital status, at least for those people who would be particularly disadvantaged by digital-only status. For ease of reference, we call this ‘the mixed model’. The mixed model raises several further design questions: whether the scheme would provide physical proof automatically to all status-holders, or only on application; whether an application-based scheme would be open to all, or limited to those with a qualifying reason; whether any application fee would be charged to defray some or all of the cost of the scheme (and if it should be waived where appropriate). We lack the space here to consider each of these questions in detail. If such a scheme were sensitively implemented, however, it would reduce the discriminatory effects of the current blanket policy, without unacceptably compromising the Home Office's objectives.

Turning first to the discriminatory effects, the mixed model would address the problems identified in the second part of this paper. It would protect people in the groups we have identified – disabled people, older people, and people from Gypsy, Roma or Traveller communities – from the particular disadvantages they are exposed to under a digital-only system. It would be much easier for them to prove their status, without the need for any internet infrastructure, hardware or digital literacy. And they would be less vulnerable to the lost benefits, additional burdens and distress which might flow from being unable to prove their status.

Nor would the mixed model unacceptably undermine the Home Office's objectives. Consider first the convenience objective. From the perspective of status-holders, the mixed model would be more convenient than digital-only status. Those status-holders who prefer digital status would be free to use it, while digitally excluded status-holders would enjoy the convenience of being able to rely on their physical status. It is possible that the mixed model would be less convenient for some third parties.Footnote 140 But there are at least two reasons to doubt this claim. First, as discussed above, there are legitimate questions about whether digital status is in fact more convenient for third parties than physical status. Secondly, for third parties interacting with digitally excluded status-holders, the choice is not between physical proof and digital proof, but between physical proof and no proof at all.

Under the mixed model, the Government would incur the additional costs of producing physical proof of status for some or all EUSS applicants, depending on the design questions discussed above. But again, there is reason to doubt whether this would significantly increase the Government's overall costs. First, the Government could in principle charge a fee to recover some or all of this cost from applicants, subject to any additional concerns about accessibility or discrimination that this might raise. Secondly, by providing people with physical status, the Government would reduce the need for ongoing public expenditure on the support services discussed in the third part of this paper.

In relation to the security objective, on the available evidence it is difficult to say whether digital status or physical status is preferable. At the very least, the Home Office has provided no convincing evidence that digital-only status would provide better security overall than the mixed model. The key difference would be that, under the mixed model, digitally excluded groups would be able to rely on their physical status. But for such groups, the security benefits of digital status would be elusive. There is little point in a person's status being more secure from other people if they cannot use it themselves.

(c) Does digital-only status strike a fair balance?

The final limb of the Bank Mellat test requires a balancing of ‘the severity of the measure's effects on the rights of the persons to whom it applies against the importance of the objective, to the extent that the measure will contribute to its achievement’.Footnote 141 On our analysis, digital-only status clearly fails to strike a fair balance between the rights of individuals and the Home Office's objectives.Footnote 142 It exposes people who cannot use digital status to very serious risks, including detention, denial of legal rights, and even deportation. And when compared to the mixed model, it promises only marginal and speculative benefits. It offers the possibility of greater convenience, but only for some third parties. It may save the Government some money, but only by shifting costs onto status-holders themselves. And the security benefits remain unproven.

Conclusion

The government's digital-only status policy – at least as it is being rolled out within the EUSS – is unlawful. It indirectly discriminates against a range of groups with protected characteristics, namely disability, age and race. There have been no effective steps taken to eliminate that discrimination, there are no compelling objectives which can justify the discrimination, and there are patently alternative, less intrusive options available. Managing migration and borders is a legitimate aim for states and governments should be exploring the use of technology to improve public services. But there is no legal entitlement to do so in a way which is unjustifiably discriminatory.

Though our analysis has been based in equality law, it reveals important defects in the general policy of digital-only status. Even if our legal conclusions are not accepted, the underlying systemic risks we have identified ought to be a continuing source of concern. The appropriate course now is for the policy to be reviewed and adjusted promptly. Without such action, the roots of digital discrimination in immigration policy and administration will be allowed to spread. They may quickly grow into another Windrush.