Introduction

Undocumented status has adverse effects on whether immigrants mobilize the law to claim legal rights and better treatment. The threat of deportation (Abrego Reference Abrego2011), state surveillance (Asad Reference Asad2020), an uncertain future, and a precarious labor market position (Gleeson Reference Gleeson2010) produce fear among undocumented immigrant workers, heightening their subjugation to the pervasive authority of the law. As a result, they are less likely to make claims to government institutions or directly to their supervisors/employers for legal rights or better treatment in the workplace. This article examines instead whether and how reluctance to mobilize the law in workplaces might change with the transition to lawful permanent resident (LPR) status.

LPR status is often assumed to be empowering and result in behavioral changes. This takes for granted that LPR status changes immigrants’ legal consciousness or how they understand and act in relation to the law (Chua and Engel Reference Chua and Engel2019). Barriers to seeing the law as a resource to make workplace claims developed while working undocumented (Gonzales and Gleeson Reference Gleeson2012) may endure with LPR status. Feelings of disillusionment (Mahler Reference Mahler1995) produced by the uncertain, resource-intensive, and lengthy process of legalization (Gomberg-Muñoz Reference Gomberg-Muñoz2017; López Reference López2022; Menjívar Reference Menjívar2006; Menjívar and Lakhani Reference Menjívar and Lakhani2016) may fuel reluctance to make workplace claims. Further, high opportunity costs disincentivizing claims to rights as workers may continue given broader employment precarity in the United States (Kalleberg Reference Kalleberg2011) and the economic scarring effects of undocumented status (Kreisberg Reference Kreisberg2019). Yet, limited research analyzes how formerly undocumented immigrants make sense of LPR status (Escudero Reference Escudero2020; Gomberg-Muñoz Reference Gomberg-Muñoz2017), with little attention paid to the workplace specifically.

Should LPR status change immigrants’ willingness to make claims to rights and better treatment, place, and gender may produce divergent understandings of the law and reported claims-making behavior. Localities with more welcoming immigrant policies (Pedroza Reference Pedroza2022) – and more favorable labor protections – may promote greater mobilization of claims through belonging (Jiménez et al. Reference Jiménez, Schildkraut, Huo and Dovidio2021), opportunity structures, and critical resources (Gleeson Reference Gleeson2012; Jones Reference Jones2019). Women may forego or not engage in as much workplace claims-making relative to men (Dittrich et al. Reference Dittrich, Knabe and Leipold2014; Kugler et al. Reference Kugler, Reif, Kaschner and Brodbeck2018; Luekemann and Abendroth Reference Luekemann and Abendroth2018) due to disparities in their initial labor market position (Browne and Misra Reference Browne and Misra2003; Flippen Reference Flippen2012; Hagan Reference Hagan1998; Hondagneu-Sotelo Reference Hondagneu-Sotelo1994) and lower socio-economic returns from LPR status (Kreisberg and Jackson Reference Kreisberg and Jackson2023). Due to a paucity of studies attentive to how place and gender factor into claims-making decisions for the formerly undocumented, we do not know if and how these dynamics play out.

In this study, I examine how LPR status is understood and experienced vis-à-vis the workplace, advancing our understanding of how and why LPR status might improve upon undocumented status, as well as its limitations. Specifically, I ask: How do immigrants re-interpret and reportedly act on their standing and ability to make workplace claims once legalized? Here, workplace claims encompass formal claims to legal rights, as well as requests for raises, promotion, better working conditions, benefits, and accommodations. Drawing on in-depth interviews with 98 formerly undocumented Latino immigrants in the Los Angeles and Atlanta metropolitan areas, the data show that LPR status increases immigrants’ self-reported willingness to engage in, and follow through with, workplace claims-making.

While I found no differences in claims-making based on location, I did find gendered differences. Theoretically, obtaining LPR status should provide formerly undocumented men and women the same structural affordances. Indeed, while undocumented, both men and women reported a similar legal consciousness and anticipated similar workplace claim-making behavior as permanent residents. However, post-legalization, men and women reported different views and behaviors around workplace claims-making due to legal status being imbued with gendered relational norms. As a result, the kinds of claims made, how they were framed, and whether claims were escalated to government institutions or up the chains of command differed for men and women.

I outline three relational mechanisms that explain the increased, yet gendered claims-making behavior reported. First, both men and women made sense of LPR status in relation to their previous undocumented status. This lived reference point led them to understand LPR status as a source of opportunity and stability, changing the perceived opportunity costs of, and their investment in, making claims at work. Second, interactions with representatives of the law (i.e., judges and attorneys) drew on gender norms in the legalization process, emphasizing different factors of deservingness and implied behavioral expectations with LPR status for men and women which immigrants then internalized. Third, interactions with those in immigrants’ social networks communicated LPR status as a source of responsibility and privilege, emphasizing changes in claims-making behavior more broadly, as well as gendered responsibilities to family and community. These mechanisms produced gendered citizenship – or differences in how men and women enacted the benefits of legal inclusion, in this case in the context of work.

These findings make three main contributions. First, they highlight the significance of relationality in legal consciousness (Abrego Reference Abrego2019; e Silva Reference e Silva2022; Liu Reference Liu2023; Young Reference Young2014) for how those formerly undocumented navigate contexts like the workplace. This extends previous research by Abrego (Reference Abrego2019) using relational legal consciousness to exam categories like legal citizenship in the context of the family. Second, where extant research emphasizes women largely foregoing claims in the workplace compared to men (Dittrich et al. Reference Dittrich, Knabe and Leipold2014; Kugler et al. Reference Kugler, Reif, Kaschner and Brodbeck2018; Luekemann and Abendroth Reference Luekemann and Abendroth2018; Sauer et al. Reference Sauer, Valet, Shams and Tomaskovic-Devey2021), my findings illustrate how sources of empowerment – in this case the transition to a permanent legal status – can bolster women’s sense of standing and their reported claims-making behavior. What remains gendered, however, is the content, framing, and escalation of these claims. Third, my findings help explain the gendered occupational and wage benefits of LPR status posited by extant quantitative research (Kreisberg Reference Kreisberg2019; Kreisberg and Jackson Reference Kreisberg and Jackson2023; Lofstrom et al. Reference Lofstrom, Hill and Hayes2013).

The deleterious effects of undocumented status

Practices of exploitation, the threat of deportation, and limited institutional knowledge raise the opportunity costs of making claims to rights as an immigrant worker (Abrego Reference Abrego2011; Gleeson Reference Gleeson2010; Gomberg‐Muñoz Reference Gomberg‐Muñoz2010). Though undocumented status does not preclude immigrants from labor protections, barriers to formal education and procedural knowledge inhibit whether immigrants make claims to their rights at work (Alexander and Prasad Reference Alexander and Prasad2014; Patler et al. Reference Patler, Gleeson and Schonlau2022). Further, immigrants are often channeled into the “secondary labor market” (Piore Reference Piore1979; Waldinger Reference Waldinger2001), marked by heightened competition, instability, and limited opportunities for advancement. As such, undocumented workers are often exposed to dangerous work environments (Hall and Greenman Reference Hall and Greenman2015), subject to greater rates of wage theft (Hall et al. Reference Hall, Greenman and Farkas2010), less likely to move up in their job (Hall et al. Reference Hall, Greenman and Youngmin2019) or be provided overtime pay, and more likely to work in segregated worksites (Cobb-Clark and Kossoudji Reference Cobb-Clark and Kossoudji2000; Flippen Reference Flippen2012). Fear (Abrego Reference Abrego2011) surrounds speaking up about these circumstances, even if immigrants are aware of their labor rights (Gleeson Reference Gleeson2010). Specifically, making claims raises the potential for surveillance (Asad Reference Asad2023; García Reference García2019), removal (Dreby Reference Dreby2015), or being seen as undeserving to stay in the United States (Chauvin and Garcés-Mascareñas Reference Chauvin and Garcés-Mascareñas2012; Gleeson Reference Gleeson2010). Therefore, many undocumented immigrants forego making workplace claims (Fussell Reference Fussell2011; Gleeson Reference Gleeson2010) and “continue to work in jobs even if the pay is low or accept exploitative or illegal work conditions” (Hall, Greenman, and Farkas Reference Hall, Greenman and Farkas2010, 508).

Existing studies assume the transition to LPR status to be empowering, allowing immigrants to surpass the negative effects of previous undocumented status. To this end, studies on liminal statuses such as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) or Temporary Protected Status point to permanent residency as a transformative mechanism to move past the constraints of limited legal inclusion (Abrego Reference Abrego2018; Menjívar Reference Menjívar2017; Patler et al. Reference Patler, Hamilton and Savinar2021). Yet, few studies address exactly how and why LPR status might change how immigrants understand and act in relation to law, or how they might go about improving their wellbeing and that of their families. This article begins to tease out the social processes that contribute to the socio-economic effects of LPR status by examining how it is relationally experienced and understood vis-à-vis work.

How immigrants make sense of, and act upon, legal status

A relational legal consciousness of legal status

Drawing from Chua and Engel (Reference Chua and Engel2019, 336), I define legal consciousness as how individuals “experience, understand, and act in relation to law.” Though this conceptual lens is not without its critiques (Silbey Reference Silbey2005), a tradition has proliferated around using it to examine how state authority is (re)produced and maintained in the everyday life, thoughts, and actions of people through various legal status categories (Gleeson Reference Gleeson2010; Menjívar and Lakhani Reference Menjívar and Lakhani2016; Galli Reference Galli2020; Vaquera et al. Reference Vaquera, Castañeda and Aranda2022; Solórzano Reference Solórzano2022; Asad Reference Asad2023; Tenorio, Reference TenorioForthcoming) – largely popularized by the work of Leisy Abrego (Reference Abrego2011; Reference Abrego2018; Reference Abrego2019). Thus, legal consciousness remains useful in analyzing the diverse relationships marginalized groups have with the law and their respective cultural production (Hull Reference Hull2016).

Legal consciousness is inherently relational as it is a product of social context (Young and Chimowitz Reference Young and Chimowitz2022, 241). Most scholars studying this relationality understand it in regard to people’s relationships to another person or group (Young and Chimowitz Reference Young and Chimowitz2022, 242). Specifically, the influence of people’s perception of how others understand the law is described as “second-order legal consciousness” (Young Reference Young2014, 500). Extant research illustrates this relationality through interactions between social ties with different legal statuses. For example, Abrego (Reference Abrego2019, 663) illustrates how Latino youth in mixed-status families “come to understand their [legal status] relationally through conversations with and close observations of loved ones.” Similarly, Escudero (Reference Escudero2020, 105) argues formerly undocumented youth activists “process the meaning of their new legal status … relative to their still undocumented peers.” Such second-order effects, however, are not contained to those an individual has a shared “affinity” or “life objectives” with like family or peers (Wang Reference Wang2019, 784). For instance, interactions with attorneys and case adjudicators can also shape how immigrants internalize expectations of the law and behave accordingly (Menjívar and Lakhani Reference Menjívar and Lakhani2016).

Apart from a people-centered relationality through the influence of others’ legal consciousness, relationality can also be observed through the influence of different positions one has had relative to the law and their use as a reference point. Though often treated as static, people’s legal status can change dynamically throughout their lives, establishing a relational connection between both current and previous legal statuses. Nascent research suggests those formerly undocumented make sense of their new legal status relative to previously being undocumented. For example, Abrego (Reference Abrego2018) argues that youth who obtain DACA develop a legal consciousness characterized by optimism, pride, and belonging relative to the disillusionment and lack of motivation felt while undocumented. Escudero (Reference Escudero2020) finds that formerly undocumented activist youth interpret LPR status as a source of privilege relative to previous experiences as undocumented. Across both studies, this shift in perspective was followed by behavioral changes – whether spatial mobility or the pursuit of education and new jobs (Abrego Reference Abrego2018), or deeper engagement in social movement organizing (Escudero Reference Escudero2020). Consequently, how immigrants interpret their current legal standing relative to a previous legal standing as a lived reference point can have important meaning-making and behavioral effects.

While the above studies on the 1.25 and 1.5 generation (those who migrated as children or adolescents compared to adults) have begun to address the effects of transitions in legal status (Abrego Reference Abrego2018; Escudero Reference Escudero2020), there is unique value in the focus on first generation immigrants I undertake. First, the latter make the bulk of the undocumented population in the United States. Second, differences in age at arrival translate into differences in socialization via institutions – such as school versus work – that affect how immigrants make sense of their legal status (Gonzales and Gleeson Reference Gleeson2012) and therefore the barriers and response strategies to claims-making (Abrego Reference Abrego2011). By focusing on first-generation immigrants, I center those whose transition to life with LPR status is the most difficult and constrained.

Legal consciousness, status, and mobilization

I bridge the two interconnected branches of relationality to demonstrate the processes that allow formerly undocumented immigrants to embrace LPR status and mobilize the law in the workplace. Following Morrill et al. (Reference Morrill, Tyson, Edelman and Arum2010, 654 emphasis added), I consider legal mobilization as encompassing how “individuals define problems as potential rights violations and decide to take action within and/or outside the legal system to seek redress.” Filing formal claims with federal, state, or local agencies is an important vehicle for workers to assert their rights and foster compliance with labor and employment standards. However, this requires procedural knowledge which disadvantages working-class and immigrant workers (Alexander and Prasad Reference Alexander and Prasad2014). Further, it is not the only mechanism through which workers may see meaningful changes in the workplace. Taking an expansive approach to workplace claims, I consider formal claims to government institutions, as well as self-advocacy directed at supervisors/employers in requesting raises, promotion, better working conditions, benefits, and accommodations.

Gendered differences in immigrants’ labor market position may condition their willingness to make workplace claims with LPR status. Undocumented immigrant women are often funneled into jobs with even more restricted opportunities for upward economic mobility than men, such as domestic work, the service sector, or informal jobs. These jobs provide lower wages, social isolation, and reduced visibility (Browne and Misra Reference Browne and Misra2003; Hagan Reference Hagan1998; Hondagneu-Sotelo Reference Hondagneu-Sotelo1994). These kinds of workplace barriers may endure even as women transition to LPR status, as quantitative studies argue women face unique occupational scarring effects from experience working undocumented compared to men (Kreisberg and Jackson Reference Kreisberg and Jackson2023). Such disadvantages may produce lower work aspirations and commitment (Cassier and Reskin Reference Cassier and Reskin2000; Mueller et al. Reference Mueller2001), decreasing immigrant women’s sense of entitlement and awareness of unlawful or unfair treatment by those they work for and alongside. Thus, formerly undocumented women may largely forego making workplace claims compared to men, in line with studies on claims to better compensation (Dittrich et al. Reference Dittrich, Knabe and Leipold2014; Kugler et al. Reference Kugler, Reif, Kaschner and Brodbeck2018), discussions of career prospects (Luekemann and Abendroth Reference Luekemann and Abendroth2018), and even work accommodations (Luhr Reference Luhr2020).

Should women see an increase in their willingness to make, and follow through with, claims-making, the kind of claims they report pursuing may differ compared to men. The social interactions and ties immigrants accumulate are gendered (Carrillo Reference Carrillo2023; Jones-Correa Reference Jones-Correa1998; Menjívar Reference Menjívar2002), creating differences in the kind of messages and resources immigrants encounter. Undocumented status also challenges immigrants’ ability to meet personally or socially expected gendered behaviors – often discussed as masculine breadwinner norms for men (Walter et al. Reference Walter, Bourgois and Margarita Loinaz2004) and feminine caregiving norms within and outside the family for women (Abrego Reference Abrego, Menjívar and Kastroom2013). Though immigrants adapt to these constraints while undocumented (Abrego Reference Abrego2009; Reference Abrego2014; Enriquez Reference Enriquez2020), transitions in legal status may introduce new social pressures to meet these gendered expectations. Gender norms may also be communicated by legal actors such as judges and attorneys. Indeed, the legalization process is inflected with gendered meanings and frameworks (Salcido and Menjívar Reference Salcido and Menjívar2012) affecting who is seen as deserving of intervention (Stumpf Reference Stumpf2020) or membership (Farrell-Bryan Reference Farrell-Bryan2022). As such, gender norms and expectations promoted by legal actors and social ties may establish different understandings and motivations for workplace claims with LPR status for men and women.

Place of residence may further condition legal mobilization with LPR status. Local policies can affect access to institutional resources, social capital, and feelings of belonging – especially for those undocumented (Abrego Reference Abrego2008; Jiménez et al. Reference Jiménez, Schildkraut, Huo and Dovidio2021; Jones Reference Jones2019). Therefore, research suggests that the extent to which a locality exhibits welcomeness or restrictionism toward immigrants may affect how they navigate everyday life (Asad Reference Asad2020; García Reference García2019) and the extent to which they mobilize the law to make rights-based claims (Gleeson Reference Gleeson2012; Pedroza Reference Pedroza2022). Yet, while many aspects of subnational climate can certainly have spillover effects, those with LPR status do not face the same enforcement vulnerability, institutional restrictions, and threat of removal, as their undocumented counterparts. As a result, while salient for the undocumented experience, local variation may not be as determinant of claims-making behavior for formerly undocumented, now lawful permanent resident immigrants – at least in the context of the workplace.

Data and methods

This article draws on in-depth, timeline (Adriansen Reference Adriansen2012) interview data collected between January 2022 and May 2023 with 98 formerly undocumented, lawful permanent resident first-generation Latino immigrants across the Los Angeles (52) and Atlanta (46) metropolitan areas. This qualitative approach is apt for building on quantitative findings of socio-economic outcomes post-legalization (e.g., Kreisberg Reference Kreisberg2019; Kreisberg and Jackson Reference Kreisberg and Jackson2023) and placed-based effects on immigrant claims-making (e.g., Pedroza Reference Pedroza2022), offering insights into the processes of legal consciousness and claims-making for formerly undocumented immigrants in the labor market. While this qualitative approach renders the mechanisms and processes uncovered potentially non-exhaustive, the fact that they emerged across respondents selected from two different metropolitan areas suggests that they may be more universal than particular.

Site selection

To examine the extent to which subnational climate may affect how formerly undocumented immigrants make sense of, and act upon, LPR status, I selected two ideal-typical metropolitan areas that captured a welcoming versus hostile climate. In this process, I focused on sites that shared broad similarities making them relatively comparable to one another. Using the Migration Policy Institute’s (n.d.) Unauthorized Immigrant Population Profiles, I looked for immigrant metropolitan destination pairings with comparable undocumented demographic and economic profiles, as well as relatively comparable levels of gender representation, education, English proficiency, percent uninsured, percent at different poverty levels, work sector concentrations, and Latino immigrant representation. I also narrowed to destinations that housed a U.S. global city to capture variability in the working-class economy. This is how I arrived at the Los Angeles and Atlanta metropolitan areas as the two sites for this study.

Each metropolitan area is also situated in a specific state labor and immigration policy context. Georgia has robust preemptive anti-immigrant laws (Blizzard and Johnston Reference Blizzard and Johnston2020). Through SB 529, the state formally denies undocumented immigrants’ access to public benefits and employment, as well as empowers local authorities to carry out immigration enforcement. SB 488 bars undocumented immigrants from obtaining a state driver’s license. HB 87 allows police officers to ask for immigration documents while investigating unrelated offenses. These policies contribute to Georgia receiving a score of −90 on the Immigrant Climate Index – the second lowest state score with Arizona being the lowest – while California received the highest score in the country at 290 (Pham and Hoang Van Reference Pham and Hoang Van2018). The Atlanta metropolitan area has also implemented anti-immigrant housing ordinances that further promote exclusion (Arroyo Reference Arroyo2021). With respect to labor standards, California’s labor laws are significantly more stringent, while Georgia – as a “Right to Work” state – has weaker protections and lower union membership. I assumed these differences might affect belonging (Tropp et al. Reference Tropp, Okamoto, Marrow and Jones-Correa2018; Jiménez et al. Reference Jiménez, Schildkraut, Huo and Dovidio2021), how everyday life is navigated (García Reference García2019), and the opportunities available while undocumented (Jones Reference Jones2019), potentially influencing how formerly undocumented immigrants make sense of, and act upon, LPR status.

Eligibility criteria

Respondents in the present study: (1) were at least 18 years of age when they arrived in the United States; (2) arrived on or after 1997; and (3) spent over a year undocumented. These restrictions control, to an extent, for factors that might impact the immigrant experience and claims-making behavior. It excludes 1.25 and 1.5 generation immigrants who may – as a function of their age and socialization – have different experiences transitioning into lawful permanent residency (Diaz‐Strong and Gonzales Reference Diaz‐Strong and Gonzales2023; Gleeson and Gonzales Reference Gleeson and Gonzales2012). Restricting to those who arrived during or after 1997, contains variability in access to, and experiences of, legalization as the 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRAIRA) created 3- and 10-year bars for many paths to legalization. Finally, those who spent less than a year undocumented might have different long-term effects and outcomes with lawful status; thus, excluding them reduces the concern of skewed findings.

Sampling approach

I used four sampling and recruitment methods. First, I obtained a convenience sample by advertising the study to my personal networks who were asked to refer those they knew to be eligible to be part of the study. Second, I used purposive sampling to identify potential study participants by embedding myself in community organizations such as churches, neighborhood shops, legal service organizations, and labor centers where I posted recruitment fliers, established contact with key informants, and built rapport with future study participants. Third, I launched a study advertisement via Facebook which was restricted – using zip codes – to the greater Los Angeles and Atlanta areas. The advertisement was designed to target users who according to Meta’s data had ever lived in Latin America, were born in a Latin American country, or had a multicultural affinity (via Spanish language). If the advertisement reached someone who was not eligible, the advertisement could be forwarded across Meta’s other social media platforms. Fourth, I encouraged participants to advertise the study to those who might be eligible in their networks, that they might contact me directly.

In-depth timeline interviews

In-depth interviews were semi-structured and involved constructing a timeline (Adriansen Reference Adriansen2012) with respondents marking significant socio-economic, personal, and legal milestones that were then fleshed out and revisited throughout the interview. This allowed them to reflect on changes pre- and post-legalization. For each job respondents reported, they were asked whether they made claims to their supervisor/employer or to a government institution. Probing questions around claims to earnings, accommodations, health and safety, promotion, harassment, discrimination, job benefits, and labor rights were used. Respondents were also asked to describe their experiences in each job, with additional probes for how they handled or managed various dynamics described. This provided respondents ample opportunity to report claims in the interview. If respondents reported making claims with LPR status, they were asked the counterfactual question of whether they believed they would still have moved forward with such claims should they have remained undocumented. Those who were not asked this question answered it organically. Interviews averaged 2.5 hours and covered themes such as migration to the United States, educational and parental background, work history, experience pursuing lawful status, and aspirations for the future. Over three-fourths of respondents were interviewed at least twice. Interviews were conducted in-person and remotely, over Zoom or on the phone, in both English and Spanish.Footnote 1 Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed, translated where necessary by me, and conducted in accordance with protocols approved by the IRB at my university. Respondents were compensated with a $40 gift card after their first interview. All respondents were given pseudonyms.

Sample characteristics

On average, respondents spent 9 years undocumented and 7 years as lawful permanent residents. Table 1 below breaks down the demographics of my sample by gender, showing the men and women in my study are relatively comparable. Some differences, such as more than double the number of men legalizing via employer sponsorship compared to women, corroborate extant research’s argument of gendered differences in access to, and opportunity for, immigrants to legalize (Salcido and Menjívar Reference Salcido and Menjívar2012). In addition, Table 1 shows most of my sample for both men and women had less than the equivalent of a high school diploma while undocumented. This in conjunction with questions asking about their life growing up in their origin country and the occupation of their parents, suggesting most of my respondents’ pre-migration socio-economic status was working-class.

Table 1. Descriptive data on the formerly undocumented men and women

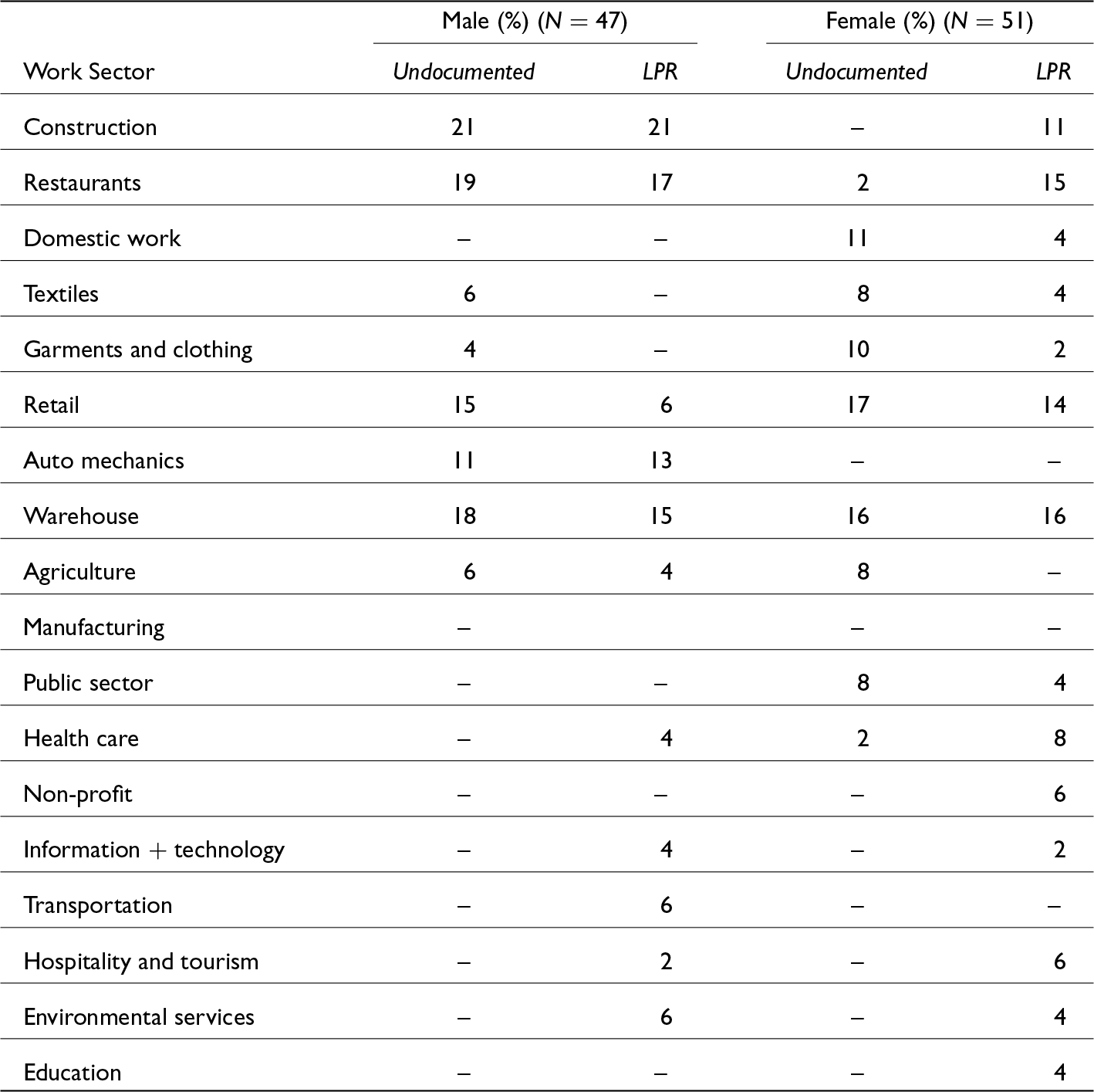

Table 2 below breaks down the work sector my sample occupied while undocumented and as lawful permanent residents by gender. As we might expect, certain work sectors were exclusively occupied by either men or women while respondents were undocumented, such as domestic work for women and construction and auto mechanics for men. However, the inclusion of other sectors and their comparable gender representation such as in agriculture, retail, warehouses, and restaurants provide comparative leverage. Table 2 also demonstrates how lawful permanent residency allowed several respondents access to new work sectors for both men and women. In addition, permanent resident women were able to move into work sectors that are less characteristic of the constrained labor opportunities of undocumented women such as construction, the public sector, health care, non-profit, and information and technology. However, some gendered differences in sector representation remain.

Table 2. Work sector by gender as undocumented and Lawful Permanent Residents (LPR)

Analytic approach

Data were collected and analyzed concurrently. Following a flexible coding approach (Deterding and Waters Reference Deterding and Waters2021), I indexed transcripts with broad codes focused on workplace claims, followed by a line-by-line review of what was indexed to identify emergent patterns. After analyzing interviews for 20 respondents, I started writing analytic memos to develop these patterns into themes that would inform further analyses. Next, I revisited transcripts and more finely coded subsections of interviews that spoke to how respondents understood their rights, range of potential action, justifications for actions taken, etc. I then examined how these codes interacted with attributes such as gender, subnational climate, work site, and experience with immigration enforcement and processing.

Relational legal consciousness vis-á-vis work with LPR status

Shifts from legal consciousness while undocumented

Nearly all of my respondents expressed a legal consciousness characterized by fear of speaking up about their rights and the normalization of their subpar treatment in the workplace while undocumented. Juan, a sanitation worker who spent long nights cleaning office buildings in downtown Los Angeles for 5 years while undocumented and into his time as a permanent resident, exemplifies this. With the threat of removal “always in the back of [his] mind,” he feared speaking-up at work while undocumented would be met with his supervisor terminating him or him being reported to immigration authorities. He also believed that filing a grievance with a government agency might trigger an immigration raid at his job given he was working under a “seguro chueco” or social security number that corresponded to someone else Juan impersonated to obtain employment (Juan, January 2022). Similar perspectives were seen among those who indicated awareness of their work rights (Gleeson Reference Gleeson2010), had higher levels of formal education (Patler et al. Reference Patler, Gleeson and Schonlau2022), and were of a middle-class background pre-migration – factors which might positively correlate with workplace claims-making. For instance, Maria Angelica, who worked in retail in Atlanta despite having an advanced technical degree from Mexico and coming from a middle-class family, shared it was better to “keep [her] head down” about the sexual harassment she experienced or not being paid for overtime while undocumented (Maria Angelica, August 2022). All but nine of my respondents reported choosing to forego making workplace claims while undocumented. Most of the nine exceptional cases were men across different work sectors who resided in the Los Angeles area, corroborating the disadvantages at the intersection of undocumented status, gendered labor market positions (Flippen Reference Flippen2012), and local differences in immigrant supports (Pedroza Reference Pedroza2022).

Across both sites, most of the formerly undocumented immigrants in my study (38 out of the 47 men; 42 out of the 51 women) self-reported an increased willingness to make, and follow through with, workplace claims. This overall increase in reported claims-making behavior was informed by how immigrants relationally understood the benefits and security of LPR status through the reference point of their lived experiences while undocumented. In the next section, I outline four interpretive effects of LPR status in relation to previous undocumented status which promoted perceptions of lower opportunity costs to, and increased investment in, immigrants advocating for themselves at work to supervisors or with government agencies.

The relative costs and investment in workplace claims-making with LPR status

LPR status provided respondents a greater sense of security via narrower grounds for deportation. For many, this meant no longer fearing being discovered as “illegal” on the job or the threat of immigration enforcement in the workplace. While other studies have found immigrants with LPR status can still feel vulnerable to state surveillance and enforcement (Asad Reference Asad2020; Chen Reference Chen2020; Gomberg-Muñoz Reference Gomberg-Muñoz2017), the respondents in my study who reported continued fears largely attributed them to settings outside the workplace. Erna, who during her 3 years with LPR status worked her way up from being a food preparer to a cook and ultimately to an assistant manager at a Korean restaurant in the Los Angeles area, explained how the reduced threat of deportation affected how she related to work:

I felt more comfortable in the (work) environment, I talked to different people, I became more curious about different positions and what people did … I felt like I didn’t need to be ready to hide at any time … I felt like I could push back when things were unfair or not right, like I had more voice. (Erna, March 2023)

Erna’s comments depict how the narrower grounds of deportation with LPR status changed how she contextualized the potential for employer retaliation to rights-based claims and her own sense of empowerment. They also signal changes in how the workplace was navigated, which can potentially expose respondents up to new knowledge and help them identify more with the situation of their coworkers that could promote future claims-making behavior.

LPR status afforded respondents the ability to better envision a life for themselves in the United States, creating a personal and economic incentive to advocate for themselves in the workplace. Some respondents who planned on return migration later in life, no longer viewed this as desirable, requiring them to redirect attention and resources toward building a better life in the United States. For example, Bonifacio, who worked in cold storage warehouses in the Atlanta area and held lawful status for six years, described:

I thought of returning to Mexico differently when my application [for adjustment of status] was approved … I started thinking about putting the money I saved for a home [in Mexico towards a home] here (in the United States) … I got to thinking about how to make more (money) since here is more expensive. (Bonifacio, June 2022)

The few ways to bring home a larger income for workers like Bonifacio were to engage in wage negotiations, take on a second job, or move into a new job, sector, or field. While not entirely off the table, the latter two options were generally less desirable for respondents like Bonifacio. Having obtained LPR status well into adulthood, making a career pivot would be “a huge adjustment,” while taking on a second job was less appealing as he was “not young anymore.” This led Bonifacio to “think twice” and feel “empowered to be more vocal about things,” which began with wage negotiations and evolved into being vocal when his check did not reflect his hours worked, when he was “sent home early because things [were] slow that day,” as well as how he could “move to a higher position” (Bonifacio, June 2022). For respondents already working toward a permanent future in the United States, LPR status fueled desires of homeownership, starting their own business, going back to school, or moving to a “nicer” neighborhood. Regardless of what desires the imagined future entailed, they bolstered immigrants’ investment in making claims that would improve their work life.

LPR status was perceived to expand immigrants’ ability to find a new or different job, altering how they weighed claims-making decisions. Being undocumented limited the kinds of jobs immigrants could pursue. Many were turned away from jobs due to their lack of employment authorization. Where respondents used illicitly obtained social security numbers to secure employment, the fear of discovery or concerns of needing to bypass verification systems again for a new job highly incentivized them to stay and constrained job-seeking. Even where employment authorization – which can be obtained without LPR status – may grant immigrants the ability to overcome these barriers, many employers were reportedly unwilling to hire immigrants with only employment authorization (Abrego and Lakhani Reference Abrego and Lakhani2015). None of these, however, were a concern with LPR status, minimizing the threat of employer retaliation via termination. To this effect, Ignacio, who transitioned from working as a painter to a lumberyard forklift driver with permanent residency in Atlanta, shared:

Before, maybe saying something would cost me my job. But at least with my papers, I felt like if it costs me my job, I won’t have as hard of a time finding another. I don’t have to worry about them checking my Social [Security Number] anymore. (Ignacio, August 2022)

Perceiving greater ease at finding new employment altered many immigrants’ sensitivity to mistreatment and lowered the perceived costs of pursuing workplace claims, even for those in more precarious jobs. Valeria, a garment worker in Los Angeles for 12 years noted: “if they let me go, I could now find a job much more easily. So, I said, no more! I wasn’t going to put up with mistreatment and stay quiet” (Valeria, February 2022).

Formerly undocumented immigrants also perceived LPR status to provide a safety net in the event their claims-making took a turn for the worse. While not absent restrictions, lawful permanent residents are eligible for social security benefits and different welfare programs. Though respondents did not see themselves utilizing such resources, knowing they were available supported new claims-making behavior. Pamela, a warehouse equipment operator in the Atlanta area who held permanent residency for 8 years, shared:

If worse comes to worst, now I was able to use some programs from the state. That changed how I saw things, because those sort of things are never really an option when you’re undocumented. (Pamela, August 2022)

Gendered shifts in workplace claims with LPR status

Despite largely expressing the same understanding of opportunity costs and investment in claims-making with LPR status, as well as anticipating making the same claims in the workplace – whether formal grievances to government agencies or self-advocacy directed toward supervisors around wages, promotion, working conditions, accommodations, and better treatment – I found gender differences in the types of claims made and how they were framed. Where extant research emphasizes women largely foregoing claims in the workplace compared to men (Dittrich et al. Reference Dittrich, Knabe and Leipold2014; Kugler et al. Reference Kugler, Reif, Kaschner and Brodbeck2018; Luekemann and Abendroth Reference Luekemann and Abendroth2018; Sauer et al. Reference Sauer, Valet, Shams and Tomaskovic-Devey2021), my findings point to how gender powerfully informs divergent behavior even amid critical sources of empowerment such as obtaining LPR status for those who spent many years undocumented.

The workplace claims of formerly undocumented men largely had direct effects on their earnings (30 out of 38). Jacobo’s workplace claims with LPR status exemplify this. Jacobo was a cook at a higher-end restaurant in Los Angeles across both his time undocumented and as a permanent resident. Upon obtaining LPR status, Jacobo asked for a raise sufficient to have his compensation match that of his co-workers, knowing he had long been paid significantly less in comparison. When Jacobo’s employer miscalculated his overtime hours he vocalized the issue, contrary to his refusal to speak out while undocumented because it “wasn’t worth” potential retaliation (Jacobo, January 2022). Another example can be seen in the case of Santos. While undocumented, Santos worked as a janitor for a hospital in the Atlanta area. Upon legalization, he did what he needed to “make more money” which involved “pushing to get exposed to new positions” and “making sure [he] was allowed to take advantage of the resources within the hospital for new opportunities.” This resulted in Santos becoming a laboratory assistant, and continually moving his way up the job ladder over the next 3 years, meeting his goal of notable pay increases over time. Where men considered multiple potential claims at the same time, those which carried direct effects on earnings were often prioritized and reported to be followed through with. The case of Andres, an armored truck security guard who held LPR status for 9 years, illustrates this. When reflecting on the workplace claims he made post-legalization, he commented the following referencing unfair treatment he considered making claims about: “I could continue to keep quiet about how they treat me, so long as I could successfully work with them to make sure the pay was better” (Andres, April 2022). Whether advocating for advancement into a new position, enforcement of labor rights, or adjustments in compensation, men’s patterned claims post-legalization directed toward earnings help explain previous quantitative research arguing men see greater wage returns from LPR status compared to women (Kreisberg and Jackson Reference Kreisberg and Jackson2023; Lofstrom et al. Reference Lofstrom, Hill and Hayes2013).

In addition, men’s reported workplace claims with LPR status were more likely to be framed as claims to legal rights (29 out of 38). In many cases, this meant formerly undocumented men acted on the knowledge of labor rights they had accumulated throughout their work history either through on-the-job training or in observing how others (with legal status) responded to unfavorable dynamics. “[Labor] rights are completely different when you have papers … they become real,” Marlon, a permanent resident for 8 years who worked as a laundry coordinator for a linen services company in Atlanta, offered. “It’s like you see and save those things in your mind and once I had my papers it was time I could do those things too,” he added, explaining his claims to reasonable accommodations due to his physical disability and wage increases commensurate with his experience (Marlon, November 2022). Eugenio, who had been a permanent resident for a little over 3 years and worked as a truck driver in the Los Angeles area, illustrates how a legal rights framing persisted regardless of whether the rights being claimed were enforceable entitlements. After obtaining LPR status, Eugenio decided to confront his boss about his unpredictable work schedule, something his other co-workers also faced. He shared:

I told [my boss], ‘I have the right to work the hours I’m supposed to, or at least be given notice about changes … the company can’t just make me lose out on hours like that … that’s illegal. (Eugenio, October 2022)

Though Eugenio’s employer was sympathetic with his claim, the erratic work schedule was not necessarily illegal. Nonetheless, Eugenio remained adamant that a legal right was violated. 2 years later, when Eugenio was in a different department, he pushed back on how he was not allowed to move into a higher position – which while disheartening is not necessarily an illegal practice either. Voicing his frustration, Eugenio offered,

You know I had seniority, so I had a right to move up. They are not allowed to just give it to someone else. That’s why I had to go and complain. I was in my right. (Eugenio, October 2022)

However, Eugenio’s contract in fact did not guarantee the consideration of seniority in employment decisions. Men’s framing of workplace claims in terms of legal rights highlight the degree of empowerment LPR status provided them, as well as its limitations given their labor rights literacy.

The more expansive approach to framing workplace claims as legal rights violations also translated into formerly undocumented men reportedly escalating their claims up chains of command or to government institutions more than the women in my study (12 out of 38 compared to 4 out of 42). Alejandro, who worked for a cannabis company and held lawful status for a little over a year, complained to his immediate supervisor about respiratory issues which he believed to be linked to the dust and chemicals he was breathing in. When taking matters into his own hands by wearing “a special mask,” he was “ridiculed” by his peers and supervisor. Believing he was “in his rights,” Alejandro escalated his concern to those above his supervisor, leading to alterations in the company’s protocols for grinding and processing cannabis (Alejandro, February 2022). Mauricio, who transitioned from landscaping while undocumented to being a package delivery worker in the Los Angeles area with lawful status, took things a step further, escalating his grievance to a state agency. Specifically, he advocated that his rights were being violated by his job not properly equipping him to work under conditions of extreme heat that contributed to “health complications,” “exhaustion,” and “frequent dizziness” (Mauricio, March 2022). The coupling of a higher likelihood to frame claims as legal rights and escalate them further suggests the claims of formerly undocumented men may have the potential for broad-reaching implications for their worksite and those they work alongside, while also potentially contributing to greater efficacy in their claims being met furthering gendered returns on LPR status.

The increased claims-making of formerly undocumented women was largely geared toward accommodations in the workplace, better treatment, and access to benefits (35 out of 42). The case of Melodia, an online merchandise fulfillment center worker in the Atlanta area, illustrates gendered differences regarding which claims took precedent. Prior to obtaining LPR status, Melodia was eying becoming a manager, practicing “by all accounts” an exceptional work ethic and determination by “always picking up extra shifts or covering for others” and outperforming her peers even if not adequately compensated (Melodia, October 2022). Yet rather than making claims that would bolster her earnings or position at work, Melodia’s claims with lawful status prioritized accessing benefits like health coverage and enforcing her legally mandated breaks. Though Melodia had been a permanent resident for 4 years when I interviewed her, she had not moved into a supervisory or managerial role in that time. Another example can be seen in the case of Leonora, who worked in a meatpacking plant across her time undocumented and with LPR status in the Atlanta area. She chose to forego planned claims for a raise and pay on par with her peers, only making claims for scheduling flexibility and to be transferred to a different team. Apart from a divergent pattern from formerly undocumented men who largely prioritized claims with direct effects on earnings, my findings indicate perhaps surprisingly that women still significantly reported leveraging LPR status to make workplace claims resulting in modest improvements to their work life.

Whereas men widely embraced a legal rights framing to their workplace claims, many women were skeptical of doing so. For some this was due to a general uncertainty around their legal rights. For example, Leonora offered the following:

I wanted to ask my boss for a raise … I had a suspicion that I was making a lot less than my co-workers, after I heard how much a few of them were making …. I didn’t want to say anything about it before (while undocumented) … but I didn’t feel as afraid about speaking up now (with LPR status) … but I also considered… Was it that I only believed that I made less than I should? Was it going to be something that they actually had to change? … I can say that this or that is my right, but if they were to say that it wasn’t— where would I go from there? (Leonora, January 2023)

Other women were aware of their legal rights but were concerned about the broad penalties a legal rights framing could raise, such as job loss or implications for future employment (Albiston Reference Albiston2005), compared to other claims or a different framing. Luisa’s case illustrates this. Luisa worked in environmental services in a private hospital that was unionized – a job she obtained within her first two years with permanent residency. She contemplated speaking up about her rights to protected leave under the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA):

I know with FMLA, when the doctor prescribes certain things you cannot do, your job is supposed to adhere to them … and if it is in your letter, they can’t punish you if you need to call off because of complications, it is supposed to protect you … but when I came back from my surgery and called out just one day because of how I was feeling I lost ten hours in work each of the next two weeks … Later when I called out a second time they told me, “You know what, Luisa, we can’t keep having this happen” … They expected I do all the same tasks as before, even though I was not supposed to as it put me in a lot of pain and could make my recovery worse … I was pissed, I wanted to say—say, you know, “Hey! Look at my FMLA!” but I didn’t want them to say I was being ‘difficult to work with’ or that I was one of those people always threatening to sue and trying to get out of work and build that reputation for myself. I also didn’t want to push them to just find any old reason to fire me. If I was going to say or advocate for something, it was better it not come from talking about my ‘FMLA rights’ (she said with air quotes). (Luisa, November 2022)

Challenges framing workplace claims as based in legal rights also meant women often did not escalate workplace claims further up a chain of command or by calling upon labor enforcement agencies, especially in comparison to men.

Many women adapted to the tenuousness of a legal rights frame by basing their claims in parenthood, civic duty to the community, and deservingness based on their work history while undocumented (31 out of 42). Claims based in motherhood emphasized supporting women’s efforts to be “good mothers.” Lizbeth, a home health aide in the Los Angeles area who had lawful status for a year, advocated for moving from a contracted worker to an employee, to access medical benefits that would go toward her children. Lizbeth was entitled to this reclassification. In Dynamex Operations West, Inc. v. Superior Court, California adopted a three-part test prescribing workers be classified as contract laborers when: work is done without the direction or control of the employer, the work itself is outside the employer’s usual line of business, and the worker has their own business or trade related to the labor being performed. Lizbeth did not meet any of these marks. Yet rather than assert her legal right, Lizbeth felt her claims would “go farther” if they were framed as her “just trying to be a good mother.” However, like several other women in my study, Lizbeth noted “not everything can be about being a good mother,” inherently limiting the claims ultimately pursued (Lizabeth, December 2022).

Claims framed as appeals to civic duty involved women’s capacity to perform acts like volunteering, community engagement, or even being a good neighbor. Illustrating this, Asunción, who oscillated between working at a 24-hour contact center and hotel throughout her time undocumented and as a permanent resident, reported requesting advancement to positions with greater scheduling flexibility. “I told my bosses, ‘Work is very important to me, but being a Christian is also very important. I need to give back to my community … I need that position to do that,’” she shared reflecting on her request to become a night auditor for the hotel and moving to a new department in the contact center (Asunción, July 2022).

Many of those who stayed in the same workplace post-legalization, framed their work claims in appeals to deservingness by referencing their demonstrated commitment to work while undocumented. This included references to having consistently worked longer shifts, frequently filling-in for co-workers, staying quiet about previous rights violations, and being overlooked for various opportunities while undocumented. For instance, Cristina, a certified nursing assistant working in a hospital operating room, recalled telling her supervisor the following when asking for a raise: “You know I’m not the kind of worker asking for these things all the time and I do my job, better than others, and have always gone out of my way to do so, so I think I deserve this one thing I’m asking for” (Cristina, May 2022). For several of the women who moved to a new line of work or workplace post-legalization, the inability to frame their claims as based in their work history while undocumented meant they continued to forego claims. While not exclusive to women, these alternative frames were a key part of women’s strategic adaptation to the gendered challenges of raising workplace claims (Marshall Reference Marshall2005), though they limited the kinds and extent of claims raised, if claims were raised at all.

The following sections outline two relational mechanisms that help explain gendered patterns in the kinds of claims made, the basis upon which they were made, and the extent to which they were escalated beyond the dyad of employee–supervisor. These mechanisms showcase how formerly undocumented immigrants made sense of LPR status and its relation to work through gendered interactions with others and others’ view of LPR status.

Legalization effects on gendered legal consciousness

Judges and attorneys raise normative ideas of gender in interactions with immigrants throughout the legalization process (Farrell-Bryan Reference Farrell-Bryan2022; Gomberg-Muñoz Reference Gomberg-Muñoz2017; Salcido and Menjívar Reference Salcido and Menjívar2012). By invoking life post-legalization across these interactions, legal actors caused some immigrants to internalize these gendered ideas and characteristics as implied obligations of the law (Munkres Reference Munkres2008) with LPR status, informing the gendered ways they later related to work.

Formerly undocumented men often described masculine notions of financial provision and economic success in the legalization process through encouragement to be entrepreneurial, pursue work-related aspirations, and better themselves economically with LPR status. This began with men’s deservingness being evaluated, in part, through their economic productivity. Indeed, many noted being positively affirmed for their dedication to work and financial provision. Take the case of Imanol, who obtained permanent residency 4 years prior to our interview after an immigration judge granted him cancellation of removal – a form of discretionary relief some immigrants in deportation proceedings are eligible for (see Farrell-Bryan Reference Farrell-Bryan2022). He recalled the judge repeatedly expressing how “hardworking” he was after hearing about his arduous shifts as a food and beverage cross-docking worker during the hearings. In our interview, Imanol also described the judge remarking several times that he was doing “the right thing as a man, as a father, contributing financially to [his] son’s life” despite the mother of his son and him never having been married and not being romantically involved for years. In closing the case, the judge connected these characteristics meriting legal membership to Imanol deserving to “have the opportunity to do more with his life in the United States” in continuing “to be a good citizen and a good father.” Imanol internalized these latter comments as something he had to “live up to.” To accomplish this, he first took on a “second job” to bolster his earnings. Feeling that was insufficient to demonstrate “growth” or prove he was “doing more with [his] life,” he began advocating for a promotion at work that came with “better pay, more responsibility, and respect.” Like other men in my study, Imanol also worked toward living up to LPR status by “talking about work more with people” he knew compared to when he was undocumented, so they could “give advice” and “tell [him] about different opportunities” when he was “lost” or felt “stuck” (Imanol, October 2022). Therefore, legal actors contribute a second-order understanding of LPR status through case evaluation and in referencing life post-legalization; men then internalize this, catalyzing reportedly new behaviors supporting future claims-making.

Diego’s case illustrates how a similar second-order understanding of LPR status can be internalized even among men who faced different economic circumstances, were not in heterosexual partnerships, did not have children, and did not go before an immigration judge or have an interactive case evaluation to obtain LPR status. He recalled the following interaction with his attorney:

When we found out I was approved (for a Violence Against Women Act (VAWA)Footnote 2 self-petition), she cried with me … she told me that it would change my life, she was excited to see how I would change my life … She said I should revisit my dream … I forgot I even told her I thought about having my own business before … It wasn’t something I was even considering, but that made me feel like it was the right thing to do (with legal status). (Diego, May 2022)

Diego began to save and build the necessary capital to embark on his own business. He started by “asking for more pay” in the flower shop he worked for, and later asking “to be more involved with managerial work … to get more experience.” This continued even as his husband, who earned “more than enough for the two of [them],” offered to be the sole breadwinner in the relationship. However, Diego felt he needed to “make the most of the new circumstances” he found himself in.

In contrast to notions of economic provision and success for men, the legalization process largely emphasized women’s caregiving roles. Take for example, Monica, who lived in the Los Angeles metropolitan area and applied for LPR status through the sponsorship of her U.S. citizen husband Rudy. Her extreme hardship waiver outlined her integral role in Rudy’s medical care given the amputation of his right leg due to complications with diabetes, as well as her care for Rudy’s two children from a previous marriage. While far from exaggeration, the back-and-forth of crafting this documented narrative limited the understanding Monica internalized of LPR status to her role in care work rather than the financial provision typically emphasized in waivers for men. This was despite her economic contributions being vital to the stability of the family.

I felt like, well, if that’s part of why I was given the opportunity to stay here, what does that mean I can do now that I have my papers? I felt like there was an obligation to not stray from what was there in the documents, which means I feel different about doing something that would take away a bit from that, like if it meant showing up for my husband less or not being there 110% for the kids. (Monica, February 2023)

As a result, Monica chose to forego claims to move up to a better position and even enforce some of her labor rights. She did, however, push back on her supervisor challenging her ability to manage her sick and vacation days, emphasizing it as crucial to “taking care of her family.” The case of Julietta illustrates similar dynamics seen among cases that involved an immigration judge. Julietta described her judge being “won over” with how she was “raising upstanding citizens” and her “contributions to the community” in being a good neighbor and caring for two elderly women in her apartment complex:

The judge said, ‘I am granting your application. You do a lot for those around you—that’s the kind of citizen we need. It’s the kind of citizen I can only expect you will continue to be, maybe even more now that this weight is being lifted off your shoulders.’ (Julietta, December 2022)

Through these comments, the judge not only highlighted how Julietta’s care work was a critical factor denoting her deservingness for legal incorporation, but also implied expectations for how Julietta will act upon her legal status going forward with this care work in mind.

Social debt as a catalyst for gendered claims-making

Interactions within formerly undocumented immigrants’ social networks were important in shaping how they understood LPR status and encouraging gendered reported changes in workplace claims. Most respondents shared that people in their network pointed to LPR status as a source of privilege and responsibility (Escudero Reference Escudero2020). This reflects how immigrants “understand everyone’s progress in the U.S. mostly through the lens of legal status” (Abrego Reference Abrego2019, 7), as well as how even U.S.-born individuals have their own assumptions and beliefs around legal status (Gomberg-Muñoz Reference Gomberg-Muñoz2017; Enriquez Reference Enriquez2020; López Reference López2022). Across ties with those who remained undocumented, family ties, or ties to individuals representing larger social institutions (i.e., church or community leaders), interactions produced feelings of social debt or the idea that formerly undocumented immigrants owed acting upon their status in particular ways to those around them.

The LPR status of those formerly undocumented was a vehicle for the vicarious aspirations of undocumented social ties. Many of my respondents, regardless of gender, recounted these aspirations encompassing the ability to: “speak up for themselves,” “pursue new opportunities,” and materialize social mobility. To this effect, Ronaldo, a landscaper and irrigation technician in Los Angeles who had been a permanent resident for 9 years, shared:

It doesn’t happen for everyone (adjusting legal status), so for people that never have that or that have given up on that, sometimes they feel like they can live that through you … My co-worker, when that was all happening (adjustment of status), pulled me aside and said, ‘Don’t let that opportunity go to waste. Do the things, ask for things, that people like me (undocumented) can’t.’ (Ronaldo, March 2023)

Similarly, Amelia, a construction worker in the Atlanta metropolitan area who obtained lawful status 2 years prior to our interview, had a longtime friend remind her of her privileged position and the responsibility it carried:

She told me, ‘Remember that there are people like my husband, who for years have tried and tried to fix their papers, and they get nowhere … Not for nothing, but if he were in your place, every day he would take advantage of it.’ (Amelia, July 2022)

Feeling “guilty” after the interaction, Amelia asked her boss how she could qualify for benefits, was “persistent” to make sure she “stayed eligible,” and asked for a raise. Through vicarious aspirations, social ties who remained undocumented relationally produced a sense of moral obligation that informed the broader workplace claims-making of formerly undocumented immigrants.

Family ties promoted the idea that LPR status bestowed those formerly undocumented with the responsibility of repaying unmet gendered expectations while they were undocumented or in the pursuit of legalization. For women, in many cases this was tied to expectations of motherhood, though also included what it meant to be a good “wife” or “partner.” For some women, extended family noted how their investment in work while undocumented transgressed gender norms (Abrego Reference Abrego2014) that could now be repaid with LPR status. Anna Maria, who had been a permanent resident for 5 years, shared how this sentiment came from family both in Venezuela and in the United States:

I still remember my mom (in Venzuela) telling me how when you feel like you can’t give your kids security, even if it’s kind of ironic, you distance yourself from them in trying to provide that safety through something like working more. But, now that I had this blessing (adjustment of status), I should consider turning the page and actually being there for them more … When I told my cousin who lives here—in Georgia—she told me, ‘Well, you kind of owe it to them, or no?” (Anna Maria, January 2023)

The theme of women’s LPR status as a commodity to be directed toward further investment in children through physical presence and daily care practices – common gendered cultural expectations of Latina mothers (Abrego Reference Abrego2014; Abrego and Menjívar Reference Abrego and Menjívar2011) – came up for many of the women in my study with children.

These pressures were exacerbated for women who were required to leave the United States before their status was adjusted because of IIRAIRA, regardless of how present they were or the level of care provided while undocumented. The pain of family separation incurred social debt to both their children and their romantic partners. Judith, a retail worker and hairdresser in the Los Angeles area who returned to Mexico for 3 years before obtaining LPR status, shared:

The hardest thing when I came back was the fights with my kids and my husband … I wanted to take the time to finish my school and do all the things I had dreamed of, that I wanted … but as I tried, my daughter would cry telling me that she just wanted me to be home, and look at this, she even threw in my face how I left so we could be a stronger family when I returned … With my husband, we needed time to rebuild … an intimacy we lost while I was gone. It was hard for everyone, but he always reminded me of it, what we lost and what we were trying to get back … that meant more time, time at home, time that I couldn’t put into the things I wanted to do for myself and so the work dreams I had were let go. (Judith, March 2022)

Some women saw debt to their community emphasized in place of debt to children, partners, or even those who remained undocumented. This kind of social debt generally involved organizations such as churches and non-profit groups. For example, Aida’s priest encouraged her to be more involved in the church and volunteering to “show gratitude for the blessing” of God allowing her to successfully close her case for legal status (Aida, September 2022). As such, over time, Aida also negotiated a work schedule that accommodated church events and services. While limited, this allowed her to be a more engaged churchgoer, a privilege her legal status afforded her as she often missed church for work while undocumented, feeling unable to say no to her boss or ask for accommodations. For many women like those above, the pressures of social debt around caregiving expectations incentivized claims-making related to workplace accommodations, benefits eligibility, and rights to things like legally mandated breaks where they could check in on loved ones – at the expense of other claims considered.

For several formerly undocumented men, LPR status came with the social debt of meeting masculine breadwinner norms. While the masculine role of financial provider is a broader, cultural hegemonic pressure (Connell Reference Connell2005; Cooper Reference Cooper2000; Townsend Reference Townsend2002) – even among immigrant families, where men are often significant financial providers (Blau et al. Reference Blau, Kahn and Papps2011; Frank and Hou Reference Frank and Hou2015) – prior to becoming lawful residents, many formerly undocumented men made less than their partners and were co-breadwinners. While this was rarely commented on while undocumented, immigrants’ social networks communicated different expectations when men obtained LPR status. Take, for example, Guillermo, who lived in the Los Angeles area and worked as a computer technician. In our second interview, Guillermo explained:

My father-in-law made it very clear, since I no longer had the “excuse” of my papers, she (his U.S. citizen wife) shouldn’t have to be the one bringing in more money … Obviously, I can’t turn around and tell her she won’t have to work anymore, but I wanted to make more than her, even if a little bit. (Guillermo, February 2023)

Guillermo’s comments reflect the reality that for many men, whether in the Los Angeles or Atlanta area, being the sole breadwinner was not a realistic aspiration; however, even still, LPR status evoked the expectations of a gendered change in the earner status within households. Where surpassing the take-home pay of their partners was not possible, men expressed wanting to earn “at least as much” as their partner.

These pressures were exacerbated for men who were required to leave the United States before their status was adjusted. To this effect, at a holiday gathering with Arturo, who resided in the Atlanta area and had spent 2 years as a permanent resident, his wife Samantha, offered:

After Arturo came back (from El Salvador), part of me was happy … a part of me also held resentment that, you know, for three years I held down the house largely by myself … I know it’s not fair to put that all on him, it was hard for both of us … But, I also told him, things had to look different … I was exhausted of holding everything up––now he had to do it, he had to be the one to bring home the money. (Samantha, September 2022)

For men like those above, the pressures of social debt around masculine norms of economic provision incentivized workplace claims-making in the form of wage negotiations and advocacy for promotion.

Discussion

The analysis identified several interlocking factors contributing to why the present study would find LPR status led to an overall increase in reported claims-making behavior, but gendered differences in the kind of claims reportedly made, how they were framed, and whether they were escalated. Making sense of LPR status through the reference point of having been undocumented, affected how many immigrants perceived the costs and their investment in making claims at work. This influenced shifts in how, and the extent to which, immigrants talked about work with others, sought advice, broadened their curiosity in the workplace, and their sensitivity to mistreatment. Understanding that the social networks immigrants build upon arrival, as well as the resources that flow through these networks, are gendered (Carrillo Reference Carrillo2023; Jones-Correa Reference Jones-Correa1998; Menjívar Reference Menjívar2002), some of these changes may also produce gendered differences. For instance, their broadened curiosity can expose them to gendered notions of one’s capabilities (Stockard Reference Stockard2006) and what they see as possible or acceptable in the context of paid work (Davies Reference Davies1990). To clarify, I am not arguing that this gendered socialization in the workplace would be entirely new. However, given men and women reported similar anticipated claims-making behavior with LPR status while undocumented, my findings suggest LPR status presents new opportunities for gendered socialization at work to rear itself. Moreover, interactions with legal actors, family dynamics, and extended social ties relationally encourage gendered differences in how immigrants should act upon their new legal status. These ties and interactions helped direct gendered differences in the claims ultimately made. Overall, my findings highlight how LPR status alone is insufficient to overcome certain aspects of gendered socialization and inequality vis-à-vis work and can even at times reinforce it. While some women did embrace a legal rights framing or escalated their claims up chains of command or to an agency, these women also, for instance, furthered their education post-legalization. This bolsters the idea that producing certain changes in workplace behavior for women may require lawful status to be coupled with other critical means of support, education, and self-development.

While I found gendered differences in the kinds of claims made post legalization, I found no such differences based on place of residence. Where extant research argues local differences in immigration enforcement and supports impact how undocumented immigrants navigate everyday life (Flores et al. Reference Flores, Escudero and Burciaga2019) and mobilize rights-based claims (Pedroza Reference Pedroza2022), this may not be the case for immigrants with LPR status. My respondents overwhelmingly acknowledged the federal-level benefits and protections LPR status offered, suggesting this may take greater precedence over local differences or discretion in immigration enforcement. This provides evidence of LPR status potentially creating more uniform experiences among immigrants within urban working-class economies.

There are several alternative or additional factors that could explain the findings outlined in the present study. For instance, the reported overall increase in claims-making behavior might be explained by immigrants significantly moving into different jobs or work sectors with greater opportunities to make claims post-legalization. Some formerly undocumented immigrants changed the jobs or work sectors they occupied post-legalization. However, many stayed in the same line of work or even at the same work site with the same employer. This is in line with studies finding undocumented status has considerable scarring effects on formerly undocumented immigrants’ occupational positions after they legalize (Kreisberg Reference Kreisberg2019). Regardless, I did not find significant differences in overall reported claims between those who changed jobs or work sectors and those who did not. The reported overall increase in claims-making behavior might also be explained by immigrants who legalized having a privileged pre-migration socio-economic status that influenced their post-legalization claims-making. While most of my respondents came from working-class backgrounds in their origin countries, my sample does capture diversity in pre-migration socio-economic status. Yet, I did not find patterns related to this in overall reported claims-making behavior or even in the types of claims immigrants reported having made. English-language proficiency may similarly be expected to explain differences in the reported overall increase in claims-making behavior. However, I did not find any related patterns in my sample based on English language proficiency. In my sample, more women than men improved their English-language proficiency post-legalization. Thus, it may be a contributing factor to some women’s change in reported claims-making behavior – though when asked the counterfactual question of whether they would make such claims if they had not improved their English language skills, they did not express a connection between the two. Further, these women were not exceptions to the gendered differences in the kind of claims that were observed for the vast majority of my respondents. Finally, gendered differences in reported claims could be a function of men having worked for more years than women due to gendered personal or social expectations. This would have allowed men to cultivate a greater sense of entitlement related to work and more exposure to information about how to make claims once legalized. On average, however, there were no significant differences in the length of time the women in my study worked compared to men; most began and continued working within the first year upon their arrival to the United States.

Conclusion

In this article, I examine formerly undocumented Latino immigrants’ reported willingness to make claims to their legal rights and better treatment at work, as well as their reported follow through with these claims to supervisors and enforcement institutions. Corroborating studies highlighting fear around speaking-up about violations of labor rights and exploitative treatment at work while undocumented (Abrego Reference Abrego2011; Gleeson Reference Gleeson2010), prior to legalization nearly all my respondents reported foregoing workplace claims. However, respondents overwhelmingly reported an increased willingness to make, and follow through with, such claims with LPR status. My findings suggest LPR status allows formerly undocumented immigrants to positively reinterpret their standing and ability to advocate for themselves at work.