INTRODUCTION

The Netherlands is often considered one of the prime examples of a modern welfare state. Dutch benefits are generous and income inequality is among the lowest in the EU (OECD, 2011; Reference SvallforsSvallfors, 2012). In recent years, however, the Dutch government has introduced a series of strict obligations and harsh sanctions for welfare recipients. Also, most welfare offices have adopted a punitive enforcement style. According to some critics, these changes have turned the Netherlands into a “repressive welfare state” (Reference VonkVonk, 2014; Reference TollenaarTollenaar, 2018). In this article, I pay particular attention to what these developments mean for the legal consciousness—the commonsense understandings of the law (Reference MerryMerry, 1990)—of Dutch welfare clients. For these people, more than for other groups in society, “[l]aw is immediate and powerful because being on welfare means having a significant part of one's life organized by a regime of legal rules invoked by officials to claim jurisdiction over choices and decisions which those not on welfare would regard as personal and private.” (Reference SaratSarat, 1990, p. 344) Sarat has observed that in welfare offices the legal rules themselves often remain in the shadows and clients have to rely heavily on the way that officials present and interpret the law. “The rules speak, but what [clients hear] is the embodied voice of law's bureaucratic guardians” (Reference SaratSarat, 1990, p. 345). Against this background, this article will study how Dutch welfare officials shape clients' legal consciousness.

I will explore this process through the analytical lens of relational and second-order legal consciousness (Reference AbregoAbrego, 2019; Reference Chua and EngelChua & Engel, 2019; De Sa e Reference De Sa e SilvaSilva, 2022; Reference WangWang, 2019; Reference YoungYoung, 2014; Reference Young and ChimowitzYoung & Chimowitz, 2022). Rather than analyzing legal consciousness individualistically, a growing number of studies conceptualize legal consciousness as “a fully collaborative phenomenon” (Reference Chua and EngelChua & Engel, 2019, p. 347). These studies show how people's thoughts and actions “inevitably reflect their interactions with other individuals, groups and institutions” (Reference Chua and EngelChua & Engel, 2019, p. 344). A good example of the relational approach is Reference YoungYoung's (2014) study of rural cockfighters in Hawaii. In response to the critique that previous research “centers more on identifying states of legal consciousness than on examining underlying processes” (Reference YoungYoung, 2014, p. 500), she has developed a more dynamic account of legal consciousness. Central to her approach is the idea that “[a] person's beliefs about, and attitude toward, a particular law or set of laws is influenced not only by his own experience, but by his understanding of others' experiences with, and beliefs about, the law” (Reference YoungYoung, 2014, p. 500; emphasis added). While previous studies were often limited to people's own (first-order) legal consciousness, Young also looks at a “second-order” layer of legal consciousness: “people's perceptions about how others understand the law” (Reference YoungYoung, 2014, p. 499). Reference HeadworthHeadworth (2020) has applied this approach in a recent study on welfare fraud enforcement. Based on interviews with welfare fraud workers across five different US states, he provides a compelling account of their vision of clients' legal consciousness. Moreover, his study shows how their views can shape both the law in the books and the law in action. In this article, I will complement and extend Headworth's analysis and I will focus on the other side of this relationship: how is Dutch welfare clients' legal consciousness shaped by their assessment of welfare officials' legal consciousness, and to what effect?

The shift from an individualistic to a relational approach to legal consciousness also raises new questions about the most appropriate research methodology. Reference Chua and EngelChua and Engel (2019, p. 348) suggest that “the “person-by-person” research methods used by legal consciousness scholars from the early 1960s to the present” might have to be replaced by new approaches that focus on the “observation and analysis of relationships and social interactions.” However, “what those methodologies might look like, and how they might be operationalized, is not yet apparent” (Reference Chua and EngelChua & Engel, 2019, p. 348) This article wants to contribute to this discussion by introducing an innovative research methodology. While “[m]ost legal consciousness research—including relational research—is qualitative, using in-depth interviews” (De Sa e Reference De Sa e SilvaSilva, 2022, p. 350), the present study uses quantitative research methods. This paper is based on an online survey among Dutch welfare clients and it is the first study that uses a correlation analysis to study the relational character of clients' legal consciousness. This approach will allow us to study a bigger sample than most qualitative studies. Moreover, using a correlation analysis will make it possible to study the relationship between clients' beliefs about the law and their perceptions of welfare officials' legal consciousness in more detail. These findings can be used to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of survey research and may thus contribute to the development of new research methodologies to study relational and second-order legal consciousness.

In the next section, I will briefly discuss Dutch welfare law and I will introduce the analytical framework of relational and second-order legal consciousness. I then discuss the data and methods that were used for this study. In this section I will describe the details of the survey among Dutch welfare clients, and I will explain how their own legal consciousness and their second-order legal consciousness are operationalized for this study. In the fourth section, I will use the survey findings to describe welfare clients' views about the law and their assessment of welfare officials' beliefs about the law. Moreover, I will use a correlation analysis to study the relationship between both variables. In the discussion, I will argue that Dutch welfare clients' (critical) legal consciousness is shaped by their views on the (harsh and cold) way that welfare officials understand and apply the law and I will show how this can result in a negative cycle of relational legal consciousness. Finally, I will conclude with a brief summary of the main findings and I will discuss some suggestions for future research.

WELFARE LAW AND LEGAL CONSCIOUSNESS

Over the past decades, US welfare policies have become more punitive (Reference WacquantWacquant, 2009) and “policing the poor and protecting taxpayer dollars from fraud and abuse have taken priority over providing security to economically vulnerable parents and children” (Reference GustafsonGustafson, 2011, p. 1). This equally applies to social security policy and legislation in, for example, Australia (Reference CarneyCarney, 2008), the United Kingdom (Reference AdlerAdler, 2018; Reference LarkinLarkin, 2007) and the Scandinavian countries (Van Reference Van AerschotAerschot, 2011). The “rise of the repressive welfare state” (Reference VonkVonk, 2014, p. 189) can also be observed in the Netherlands. For many decades, the Netherlands was characterized by a modern welfare state with generous benefits. In more recent years, however, there has been a “trend of introducing increasingly strict obligations and sanctions for social security claimants” (Reference VonkVonk, 2014, p. 201). The Netherlands has an extensive social security system, which includes child benefits, sick leave, disability benefits and old age pensions. Footnote 1 In this article we will focus on two of the most common types of social security: unemployment benefits (regulated by the Unemployment Insurance Act) and social welfare (bijstand) for those people who have no means or insufficient income to provide in their livelihood and who do not qualify for other social benefits (regulated by the Participation Act).

Recipients of unemployment benefits and social welfare have to comply with a number of strict obligations. Firstly, recipients have to provide all the information that might be relevant for the assessment of the right to the benefit. For example, if there is a change in earnings or in the household situation this should be immediately reported. If one withholds relevant information or gives false information in order to gain financial advantage, this can be sanctioned with heavy fines. Secondly, recipients also have to fully cooperate with the welfare office. Among other things, this means that recipients have to apply for a job as much as possible and they always have to accept a job offer. If one fails to cooperate, this can be sanctioned by withholding benefit rights. In 2012, these obligations and their sanctions were even more tightened when the Dutch government introduced the Welfare Fraud Act. The government introduced this Act with the aim of “drastically increasing fines and – in the case of reoffending – barring those involved from the entire social security system” (Reference VonkVonk, 2014, p. 191). The Act increased the maximum fine for welfare fraud from 2000 Euro to a fine corresponding to the maximum amount of money that the fraudulent recipient was receiving as benefit. In practice, this may amount to 50,000 Euro. Moreover, the finding that an offense has been committed will now automatically result in the decision to impose a fine (Reference TollenaarTollenaar, 2018).

The rise of the Dutch “punitive welfare state” (Reference LarkinLarkin, 2007) is also reflected in the way that welfare officials enforce the Welfare Fraud Act and other relevant welfare regulations. Other research has demonstrated that, in theory, welfare officials can choose between two different approaches in response to rule violations: a “persuasive” (accommodative, compliance-based) approach and a “punitive” (sanctioning or deterrent) approach (De Reference De Winter, Hertogh, Sullivan, Dickinson and HendersonWinter & Hertogh, 2020). The persuasive approach is goal-oriented and normative. Officials use persuasion, negotiation and education (Reference HutterHutter, 1989, pp. 153–154). By contrast, the punitive approach primarily focuses on detecting and responding to rule-violations. Officials give penalties for observed violations and make limited use of consultation and negotiation (Reference ReissReiss, 1984, pp. 23–24; Reference ScholzScholz, 1984, p. 123). In the past, Dutch welfare offices mostly used a persuasive approach as they embraced an enforcement philosophy that is shared by many other Dutch enforcement agencies and which is often summarized with the popular motto: “Soft when possible; tough when necessary” (see, e.g., VWA, 2009). However, in recent years this motto has been completely reversed. Nowadays, most welfare offices focus on fighting welfare fraud and prefer a punitive enforcement style (Reference Hertogh, Bantema, Weyers, Winter and de WinterHertogh et al., 2018; Reference VonkVonk, 2014). To study what these developments in social security legislation and policy mean for the commonsense understandings of the law of Dutch welfare clients, the article will use the analytical lens of relational and second-order legal consciousness.

Legal consciousness

For welfare clients, legal rules are more relevant than for most other people. “Law is, for people on welfare, repeatedly encountered in the most ordinary transactions and events of their lives” (Reference SaratSarat, 1990, p. 344) and legal rules and practices play a central role in determining “whether and how [they] will be able to meet some of their most pressing needs” (Reference SaratSarat, 1990, p. 344). For this reason, it is important to understand welfare clients' legal consciousness. Legal consciousness studies seek to understand “the way in which law is experienced and interpreted by specific individuals as they engage, avoid, or resist the law or legal meanings” (Reference Silbey, Smelser and BaltesSilbey, 2001, p. 8626). In recent years this approach has become increasingly popular, both in the United States and in Europe (see, e.g., Reference SilbeySilbey, 2005; Reference HertoghHertogh, 2018; Reference HallidayHalliday, 2019; Reference Chua and EngelChua & Engel, 2019). Scholars of legal consciousness use the analysis of, for example, the workplace (Reference Albiston, Fleury-Steiner and NielsenAlbiston, 2006; Reference HoffmanHoffman, 2003; Reference MarshallMarshall, 2003, Reference Marshall2005, Reference Marshall, Fleury-Steiner and Nielsen2006), economic markets (Reference LarsonLarson, 2004), juries (Reference Fleury-SteinerFleury-Steiner, 2003, Reference Fleury-Steiner2004), social movements (Reference FritsvoldFritsvold, 2009; Reference KirklandKirkland, 2008; Reference KostinerKostiner, 2003, Reference Kostiner, Fleury-Steiner and Nielsen2006), public spaces (Reference NielsenNielsen, 2000, Reference Nielsen2004), the border (Reference AbregoAbrego, 2011; Reference KubalKubal, 2015) and the Internet (Reference LagesonLageson, 2017) to study how law is acted upon and understood by ordinary citizens. Reference Chua and EngelChua and Engel (2019) have identified three schools of legal consciousness research: Identity, Hegemony, and Mobilization. The Identity school “treats individual subjectivity in relation to law as the explanandum – the phenomenon demanding critical investigation and analysis” and emphasizes “the fluidity and multiplicity of legal consciousness” (Reference Chua and EngelChua & Engel, 2019, p. 337). The Hegemony school “views law as a pervasive and powerful instrument of state control […] even when it is not applied directly or instrumentally” (Reference Chua and EngelChua & Engel, 2019, p. 339). And the Mobilization school studies “law's potential for transforming society, particularly by deploying rights that are intended to achieve justice” (Reference Chua and EngelChua & Engel, 2019, p. 340). Similarly, Reference HallidayHalliday (2019) has described four broad methodological approaches to legal consciousness research: a critical approach, an interpretative approach, a comparative cultural approach, and a law-in-action approach.

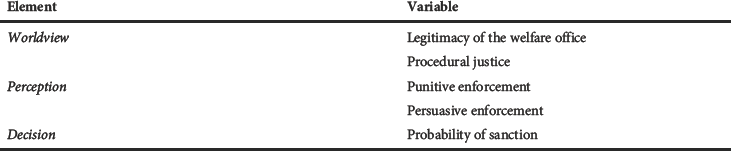

Building on previous studies, this article defines legal consciousness as “the ways in which people experience, understand, and act in relation to law” (Reference Chua and EngelChua & Engel, 2019, p. 336). The discussion of legal consciousness in this article falls under the Identity school (Reference Chua and EngelChua & Engel, 2019), using what Reference HallidayHalliday (2019) refers to as the interpretive approach. The central concern of this article is not “to document law's dominance” or to “explore the circumstances under which people deploy the law to protect their interests” (Reference Chua and EngelChua & Engel, 2019, p. 341). Instead, this study is motivated by “the simple desire to understand how ordinary's people behaviour responds to their subjective perceptions of law” (Reference HallidayHalliday, 2019, p. 865). My main interest is how Dutch welfare clients' legal consciousness is shaped by their assessment of welfare officials' beliefs about the law. To analyze welfare clients' legal consciousness in more detail, I will use Reference Chua and EngelChua and Engel's (2019, p. 336) helpful distinction of three (interconnected) “elements of subjectivity”: worldview, perception, and decision. Worldview refers to “individuals' understanding of their society, their place in it, their position relative to others, and, accordingly, the manner in which they should perform social interactions.” (Reference Chua and EngelChua & Engel, 2019, p. 336) It influences “how they perceive and respond to new experiences – and whether they should mobilize the law.” (Reference Chua and EngelChua & Engel, 2019, p. 337) Perception refers to individuals' interpretation of specific events. “For individuals who perceive an event as unexceptional, law may seem immaterial; for those who perceive the same event as violative of interests or rights, law may seem significant.” (Reference Chua and EngelChua & Engel, 2019, p. 337) Decision refers to individuals' responses to events. “Decision may at times involve deliberate choices to use the law but at other times to leave it dormant.” (Reference Chua and EngelChua & Engel, 2019, p. 337). In this article, these three elements together constitute welfare clients' legal consciousness.

As will be discussed below, several law and society scholars have applied the analytical lens of legal consciousness to study how welfare clients experience, understand, and act in relation to welfare law. In one of the first studies of its kind, Reference SaratSarat (1990) has conducted ethnographic observations of legal services in two US cities. He concludes that “legal consciousness is, like law itself, polyvocal, contingent and variable” (Reference SaratSarat, 1990, p. 375) On the one hand, the legal consciousness of the welfare poor is “a consciousness of power and domination, in which the keynote is enclosure and dependency” (Reference SaratSarat, 1990, p. 344). On the other hand, their legal consciousness is also “a consciousness of resistance, in which welfare recipients assert themselves and demand recognition of their personal identities and their human needs” (Reference SaratSarat, 1990, p. 344). This contingent and variable character of legal consciousness is also reflected in other research among welfare clients. According to some studies, clients question the legitimacy of welfare law. Reference Edin, Jencks and JencksEdin and Jencks (1993) write for example:

“We have […] created a welfare system whose rules have no moral legitimacy in recipients’ eyes. […] It is a feeling bred by a system whose rules are incompatible with everyday American morality, not by the peculiar characteristics of welfare recipients.” (Reference Edin, Jencks and JencksEdin & Jencks 1993, p. 212).

When writing about his findings about women receiving welfare, Reference GilliomGilliom (2001) reaches a similar conclusion:

“It seems clear that their legal consciousness is one of entrapment, fear, and some mystification, rather than the sort of empowering ascension to rights we might see elsewhere.” (Reference GilliomGilliom, 2001, p. 92).

Other studies argue, however, that although clients are critical about specific legal rules and practices, they still lent their overall legitimacy to the welfare system. Reference GustafsonGustafson (2011), for example, describes welfare clients' legal consciousness as “living within and without the rules”:

“Sometimes the interviewees lived within the rules, both specific and abstract, of welfare. At other times, however, they lived without the rules – sometimes because they did not know the rules, sometimes because their economic or family needs outweighed their compliance with the rules, sometimes because they were simply flouting the rules.” (Reference GustafsonGustafson, 2011, p. 93).

She concludes that “[f]or the most part […] the welfare recipients I interviewed expressed support for the existing rules.” (Reference GustafsonGustafson, 2011, p. 148).

Relational turn

One of the most interesting developments in the recent literature is, what Reference Chua and EngelChua and Engel (2019, p. 344) describe as, “the relational turn” in legal consciousness research. This refers to a trend that a growing number of studies emphasize the relational nature of legal consciousness. Reference AbregoAbrego (2019, p. 663) found, for example, that young adults who grow up in Latino mixed-status families “come to understand their juridical category relationally through their conversations with and close observations of loved ones.” Consequently, “family and loved ones' experiences were central to study participants' development of legal consciousness.” (Reference AbregoAbrego, 2019, p. 664) Similarly, based on her ethnographic study in Hawaii, Reference YoungYoung (2014, p. 516) concluded that “[p]eople orient to law and develop understandings of order and disorder in various setting based partly on the beliefs they think others hold.” She, therefore, not only looks at people's own (first-order) legal consciousness, but also at their second-order legal consciousness (their assessment of other people's beliefs about law).

The relational perspective is also important to understand welfare clients' legal consciousness. While in earlier studies this remained largely implicit (Reference GustafsonGustafson, 2011; Reference SaratSarat, 1990), Reference HeadworthHeadworth (2020) has used the concept of relational (and second-order) legal consciousness as the central focus of his study. Based on interviews with welfare fraud enforcement workers across five different US states, he describes their assessment of welfare clients' legal consciousness. These officials view clients with “suspicion and distrust” (Reference HeadworthHeadworth, 2020, p. 329). Fraud workers believe that most clients use their informal knowledge of the rules (“street policy”) to work the system and maximize their benefits. In their view, “clients deploy their policy understandings strategically, avoiding reporting income-earning significant others to bolster their program eligibility” (Reference HeadworthHeadworth, 2020, p. 330). (Reference HeadworthHeadworth's 2020) study gives us a better understanding of the role of legal consciousness in the complex relationship between welfare officials and welfare clients. However, because of its focus on the position of officials, our view of the ideas and perceptions of clients is rather limited. We still know fairly little about the way in which clients perceive and experience welfare law and welfare law enforcement. This article wants to fill this void and will therefore focus on the other side of the official/client relationship. How do Dutch welfare clients perceive welfare officials' legal consciousness, and to what effect?

Thus far, most scholars have used the terms “relational” and “second-order” legal consciousness interchangeably. However, in a recent article Reference Young and ChimowitzYoung and Chimowitz (2022) have suggested to disaggregate both terms. In their view, we can think about relational legal consciousness as “an umbrella term referring to any way Person's A legal consciousness is shaped by his relationships to another person or group” (Reference Young and ChimowitzYoung & Chimowitz, 2022, p. 242; emphasis added). By contrast, second-order legal consciousness can be understood as “a more specific term” that refers to “Person's A's beliefs or impressions about the beliefs, attitudes, impressions, and inclinations of Person B (or any group) with regard to law” (Reference Young and ChimowitzYoung & Chimowitz, 2022, p. 242; emphasis in original). In this interpretation of second order legal consciousness and relational legal consciousness, “[t]he former is a subset of the latter” (Reference Young and ChimowitzYoung & Chimowitz, 2022, p. 242). Similar to Reference Young and ChimowitzYoung and Chimowitz (2022), I will use the (umbrella) term relational legal consciousness to describe the general research approach of this study. Rather than analyzing welfare clients' legal consciousness individualistically, I will consider how their worldviews, perceptions and decisions are shaped by their relationships with welfare officials. Footnote 2 In addition, and more specifically, this study will focus on welfare clients' second-order legal consciousness. The empirical research will analyze welfare clients' beliefs, attitudes, impressions, and inclinations of welfare officials with regard to law. In other words, how do welfare clients assess welfare officials' worldviews, perceptions and decisions—and to what extent are their own worldviews, perceptions, and decisions shaped by those assessments? In short, this article will study “both second-order legal consciousness (specifically) and relational legal consciousness (more generally)” (Reference Young and ChimowitzYoung & Chimowitz, 2022, p. 242).

DATA AND METHODOLOGY

Legal consciousness studies have used both quantitative and qualitative research methods (see Reference Horák, Lacko and KlocekHorák et al., 2021). However, the interest in people's subjective understanding of law “usually leads researchers towards qualitative research methods, most often qualitative interviews” (Reference HallidayHalliday, 2019, p. 866). It has been argued that this qualitative approach enables us to move away from a narrow “attitudinal conception” (Reference Ewick and SilbeyEwick & Silbey, 1998, p. 36) of legal consciousness and a “predominant focus on measurable behavior” (Reference SilbeySilbey, 2005, p. 327) and it allows researchers to focus more on meanings and interpretations instead. However, in studying relational and second-order legal consciousness, a qualitative approach also has several limitations. In previous qualitative studies several important questions were still left unanswered. For example, “[w]hen does a person's perceptions of others' beliefs influence that person's relationship to the law?” and “[a]re certain aspects of legal consciousness more relationally influenced than others?” (Reference YoungYoung, 2014, p. 526) To address some of these limitations, this study uses a different approach. Following the example of previous quantitative studies (e.g., Reference Blackstone, Uggen and McLaughlinBlackstone et al., 2009; Reference HardingHarding, 2011; Reference Hertogh and KurkchiyanHertogh & Kurkchiyan, 2016; Reference Horák, Lacko and KlocekHorák et al., 2021; Reference MarshallMarshall, 2003; Reference MoustafaMoustafa, 2013; Reference Young and BillingsYoung & Billings, 2020), this study is based on an online survey among Dutch welfare clients. Moreover, unlike previous research, this article is the first that uses a correlation analysis to study the relational character of clients' legal consciousness.

Participants

A total of N = 1305 Dutch welfare clients completed the survey. Footnote 3 These survey participants consisted of two groups: unemployment benefit recipients (N = 709) and social welfare recipients (N = 596). Participants were recruited from a representative panel (TNS-Nipobase), which was created and managed by an online survey company from the Netherlands. The data were collected in March 2016. For this study, a representative sample of welfare clients was drawn based on age, gender, level of education and residency. In our sample, respondents were between 19 and 83 years old (M = 49,40; SD = 11,26), 61% were female and 32% had a low education (elementary school and vocational training). Since all respondents received similar welfare benefits, there was little variation in income.

Variables and measures

The survey was originally designed to study welfare clients' experiences with welfare fraud enforcement (Reference Hertogh, Bantema, Weyers, Winter and de WinterHertogh et al., 2018; Reference Hertogh and BantemaHertogh & Bantema, 2018). However, after analyzing the data it became clear that many of the survey items are also indicative of welfare clients' perceptions of law. Therefore, in this study several elements from the original survey were re-used to analyze welfare clients' legal consciousness. A complete list of items for every scale is displayed in Appendix A. The survey focuses on two groups of variables: (i) clients' own legal consciousness (how do welfare clients experience, understand, and act in relation to law?); and (ii) clients' second-order legal consciousness (how do welfare clients assess welfare officials' legal consciousness)? The survey mostly contained closed questions. Four questions (asking clients about their communication and experiences with the welfare office) were followed by an open field, where the respondents had the opportunity to motivate their answers in their own words. Footnote 4 These accounts were not (statistically) analyzed as such but are used to illustrate the survey results.

How do welfare clients experience, understand, and act in relation to law?

Reference Chua and EngelChua and Engel's (2019) three “elements of subjectivity” were used to operationalize welfare clients' legal consciousness (left side, Figure 1; see Appendix B). Worldview refers to individuals' understanding of their place in society, their position relative to others, and whether they should mobilize the law. To assess welfare clients' “worldview,” the survey used the scale of respondents' perceived obligation to obey the law. Perception refers to individuals' interpretation of specific events and their understanding of the significance of law in relation to these events. To assess welfare clients' “perception” of Dutch welfare law, the survey used two scales to measure their level of support for two important legal obligations in the Dutch social security system (which were briefly discussed in Section 2 of this article): their support for the obligation to report extra income and their support for the obligation to apply for a job. Decision refers to individuals' responses to events and their deliberate choice to use or ignore the law. To analyze welfare clients' “decision” in relation to welfare law, the survey measured four types of (self-reported) compliance: their overall compliance, their compliance with the obligation to report extra income, their compliance with the obligation to apply for a job, and their intended future compliance.

Figure 1. Relational legal consciousness.

How do welfare clients assess welfare officials' legal consciousness?

Chua and Engel's (2019) three “elements of subjectivity” were also used to operationalize welfare clients' second-order legal consciousness: their assessment of welfare officials' beliefs about the law (right side, Figure 1; see Appendix B). Reference Chua and EngelYoung (2014, p. 502) describes second-order legal consciousness as “a person's beliefs about the legal consciousness of any individual besides herself, or of any group whether or not she is part of it.” (emphasis added) Likewise, the items in this section do not describe welfare clients' assessment of individual welfare officials' beliefs about the law, but rather welfare officials' collective orientation to the law. However, for many people, welfare officials' beliefs about the law are probably quite vague and abstract. This makes it more difficult to translate into direct survey items then their own legal consciousness. In social science, when direct measures are unobservable or unavailable, researchers sometimes use an indirect (or “proxy”) measure. Reference YoungMoore and Casper (2006), for example, studied the abstract notion of “spirituality in the workplace” by focusing on perceived organizational support, affective organizational commitment and intrinsic job satisfaction. In a similar way, this study uses several “proxy measures” to analyze welfare clients' assessment of welfare officials' legal consciousness. Rather than asking welfare clients directly how they assess welfare officials' beliefs about the law, these items ask clients about their observations of welfare officials and their actions. Indirectly, these items also show how clients assess the ways in which welfare officials experience, understand, and act in relation to law. For example, asking clients how they perceive the enforcement style of their welfare office also tells us if they think that welfare officials see the law as a way to punish them or as a tool to help them. In the section below, it is explained in more detail which survey items (indirectly) reflect welfare clients' assessment of welfare officials' worldviews, perceptions and decisions.

To analyze welfare clients' assessment of welfare officials' “worldview,” the survey used one direct scale: “the perceived legitimacy of the welfare office” and one proxy scale: “the perceived procedural justice of the welfare office.” These items give us a good indication of welfare clients' perception of the first element of welfare officials' collective legal consciousness: how officials understand the relationship with welfare clients, how officials understand the manner in which they should perform social interactions with clients; and how they see the role of the law in these interactions. To analyze welfare clients' understanding of welfare officials' “perception,” the survey used two proxy scales to assess the enforcement style of welfare offices: the perceived level of punitive enforcement and the perceived level of persuasive enforcement. These items give us a good indication of welfare clients' assessment of the second element of welfare officials' collective legal consciousness: how officials interpret specific events that are related to their clients' (non) observance of welfare benefits rules; and what officials see as the most appropriate role of the law in these events. To analyze welfare clients' perceptions of welfare officials' “decision,” the survey used the proxy scale of the perceived probability of sanction. This item gives us a good indication of welfare clients' assessment of the third element of welfare officials' collective legal consciousness: how will officials respond when they break the rules and how will they use the law?

RESULTS

Based on the survey results, we can now analyze important elements of welfare clients' own legal consciousness and their assessment of welfare officials' legal consciousness. Descriptive statistics are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1 Descriptive statistics.

Welfare clients' legal consciousness

The first set of survey data looks at welfare clients' own legal consciousness. Focusing on their “worldview,” most welfare clients self-report that they are generally law-abiding. Nearly two-thirds (63.8%) of respondents feel that people should obey the law even if it goes against what they think is right. Almost half (48.5%) of them also think that disobeying the law is almost never justified. Two-thirds of respondents (66.7%) say that they always try to obey the law, even if they do not agree with it.

When we look at their “perception,” welfare clients seem to be more critical when it comes to specific provisions of Dutch welfare law. More than two-thirds of them (68.4%) claim they have no problem with the fact that the welfare office can request their income. However, just one in two (52.1%) agrees with the provision that they have to declare all their income and a similarly sized group says that, in their view, failure to report extra income should always be considered benefit fraud (46.9%). There is even less support for the other obligation. One in four (26.8%) agrees that if people do not do their best to find a job, they should be cut back on their benefits and even a smaller group (19.8%) thinks that over time you should accept all jobs. Moreover, almost one-third (29.6%) of respondents think it is ridiculous that they are being told how often they should apply for a job.

Finally, focusing on welfare clients' “decision,” most of respondents say: “I do my best to comply with the welfare benefits rules” (88.1%). Furthermore, a large group (70%) says that they pass on as much information as possible to the welfare office. However, they seem less willing to comply with some of the other benefit obligations. While most of them (80%) claim that they always report (extra) income to the welfare office, a smaller group (57%) says that when they occasionally get paid in cash, they will report this to the welfare office. Likewise, although almost two-thirds (61.9%) of respondents say that they do their best to find a job as soon as possible, one-third (29%) also say that they do not apply for a job more than necessary. From our group of respondents, 43.5% claim that they will do their best to cooperate with the welfare office and 45.2% say that, from now on, they will do what the welfare office asks of them.

Combining all three elements of welfare clients' legal consciousness, the survey data support Reference Moore and CasperSarat's (1990, p. 375) earlier finding that “legal consciousness is, like law itself, polyvocal, contingent and variable.” With regard to the law in general, and echoing Reference SaratGustafson's (2011, p. 48) earlier findings, most welfare clients seem to express support for the existing rules. On the other hand, there are also indications that, with regard to several specific provisions of Dutch welfare law, welfare clients are more critical about the law and less willing to comply with the legal rules. Similar to some of the findings from previous studies, Dutch welfare clients frequently “act strategically in relation to legal structures and authority in pursuit of desired outcomes” (Reference GustafsonHeadworth, 2020, p. 329) and sometimes question the legitimacy of welfare law (see Reference HeadworthEdin & Jencks, 1993; Reference Edin, Jencks and JencksGilliom, 2001).

Welfare clients' assessment of welfare officials' legal consciousness

The second set of survey data gives us a good indication of welfare clients' second-order legal consciousness: their assessment of welfare officials' beliefs about the law. Focusing on officials' “worldview,” most welfare clients think that welfare officials are not really interested in their personal circumstances when they apply the law. Although half of them (51.8%) think that the welfare office fulfills its commitments to benefit recipients, only a small group (17.8%) believes that the welfare office always acts in the interest of benefit recipients. Some people (19.3%) even feel that the welfare office abuses the vulnerable position of clients. Clients are also critical about the level of procedural justice. Half of our respondents (49.4%) say the welfare office honors its commitments. Yet, only one in three (31.4%) says that the welfare office treats clients fairly and a similar number (31.4%) says the welfare office treats people with respect. Also, one-third of respondents (33.7%) say that the welfare office explains their decisions and allows welfare clients to tell their side of the story (32.1%).

With regard to officials' “perception,” most welfare clients believe that welfare officials use a rather strict interpretation of the welfare benefits rules and prefer a punitive enforcement style. From our group of respondents, 53.9% say that the welfare office is like a policeman, who will punish them if they do not comply with the rules. Also, 61.9% say that the welfare office threatens them with punishment if they do not regularly apply for a job and the welfare office puts them under pressure to look for work (38.1%). Yet, some clients perceive a more persuasive enforcement style. They see the welfare office as their teacher (39%) or their coach (24.9%). In their view, the welfare office explains what is expected from them (60%), encourages them to find a job (39.2%) and gives useful tips (28.1%).

Finally, focusing on welfare officials' “decision,” welfare clients think that breaking the rules will not go unnoticed. Most respondents (70.8%) think that there is a good chance that their welfare office checks if they comply with the rules. Likewise, most clients think that their welfare office will find out if they do not report their income (74.1%) or if they do not look for a job (68.7%). Finally, many respondents (81.2%) think that when the welfare office finds out that you do not comply with the rules, you will most likely be fined.

Combining all three elements gives us a good idea of welfare clients' second-order legal consciousness. On the one hand, they see that welfare officials stress the importance of welfare obligations and legal procedures. On the other hand, they also see that officials use the law as an instrument to serve their own policy interests. In their view, welfare officials adhere to the letter of the legal rules (e.g., when they apply strict sanctions when clients fail to comply with the obligation to apply for a job), but they do not follow the spirit of the law (and assist clients to find a job in a way that takes into account their personal circumstances). For most clients, the central feature of welfare officials' legal consciousness is a high degree of—what Reference GilliomKagan (1978) in his seminal work on regulatory justice has described as—“legalism.” In their view, welfare officials' collective attitude toward the law can be best described as: “the mechanical application of rules without regard to their purpose, without regard for the fairness or substantive desirability of the results produced by applying the rules” (Reference KaganKagan, 1978, p. 92). Welfare clients strongly criticize—what they see as—the harsh and cold interpretation of welfare law and they “demand recognition of their personal identities and their human needs” (Reference KaganSarat, 1990, p. 334).

Correlations

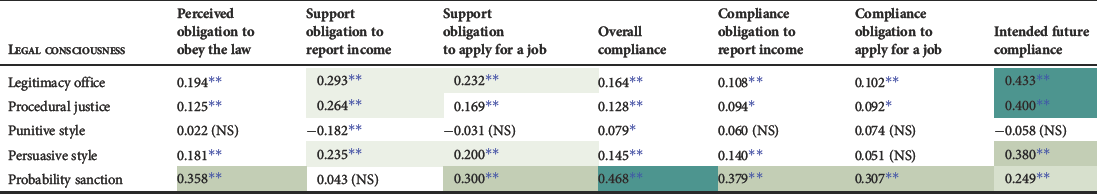

The principal focus of this study is the relationship between welfare clients' own legal consciousness and clients' assessment of welfare officials' collective legal consciousness. In statistics, a common way to study the relationship between two variables, is by analyzing their correlation. Footnote 5 However, correlation does not imply causation. Correlation between two variables indicates that changes in one variable are associated with variations in the other variable. Correlation does not mean that the changes in one variable actually cause the changes in the other variable. A correlation matrix is useful to summarize a large amount of data and to see patterns in the relationship between variables. In Table 2, welfare clients' own legal consciousness is displayed on the horizontal axis and clients' assessment of welfare officials' collective legal consciousness is displayed at the vertical axis. The correlation coefficients (Spearman's r s) reflect the direction (positive or negative) and the strength of the relationship between the two variables. Footnote 6 In general terms, 0 indicates no linear relationship, −1 indicates a perfectly negative linear correlation between two variables; and 1 indicates a perfectly positive linear correlation between two variables. In this study, we will focus on all relations between 0.2 and 0.4 (see highlighted cells in Table 2). According to the most commonly used interpretation of the r s values, correlation coefficients of 0.2 indicate a weak relationship, coefficients of 0.3 indicate a weak to moderate relationship, and coefficients of 0.4 indicate a moderate to strong relationship (Reference SaratAkoglu, 2018). This helps us to analyze which elements of welfare clients' legal consciousness are related to their assessment of welfare officials' beliefs about the law and which aspects matter more than others.

TABLE 2 Correlation matrix.

Abbreviation: NS, not statistically significant.

* p < −0.05;

** p < 0.01.

Reading from left to right, Table 2 shows that there is a relationship between welfare clients' own legal consciousness and their assessment of welfare officials' collective legal consciousness. This is reflected in the highlighted cells in Table 2. Footnote 7 However, not all elements of their legal consciousness are relationally influenced by the same factors. Clients' “worldview” (perceived obligation to obey the law), clients' “perception” (support for the obligation to report income, support for the obligation to apply for a job) and one element of clients' “decision” (intended future compliance) correlate with several aspects of officials' orientation to the law. By contrast, most elements of clients' “decision” (overall compliance, compliance with the obligation to report extra income, compliance with the obligation to apply for a job) only correlate with the probability of sanction, but with no other aspect of officials' collective legal consciousness.

Reading from top to bottom, Table 2 shows that certain aspects of how clients perceive welfare officials' legal consciousness are more important than others. Clients' understanding of officials' “worldview” (legitimacy of the welfare office, procedural justice) correlates with several elements of their own legal consciousness (except most types of compliance). This is also the case for one aspect of clients' understanding of officials' “perception” (persuasive enforcement), while another aspect (punitive enforcement) is not related to any aspect of clients' legal consciousness. Clients' assessment of welfare officials' “decision” (probability of sanction) correlates with most elements of their own legal consciousness (except their support for the obligation to report extra income).

Finally, Table 2 also gives us an indication of the strength of the relationship between welfare clients' own legal consciousness and their perceptions of welfare officials' legal consciousness. The highest correlation coefficient in Table 2 refers to the relationship between clients' overall compliance and the probability of sanction (r s = 0.468). There is a similar relationship between clients' intended future compliance and three aspects of their understanding of welfare officials' collective legal consciousness: the perceived legitimacy of the welfare office (r s = 0.433), the perceived level of procedural justice (r s = 0.400) and the perceived level of persuasive enforcement (r s = 0.380).

DISCUSSION

The survey findings not only show how Dutch welfare clients think about welfare law, but this study also contributes to our conceptual and theoretical understanding of legal consciousness.

Relational nature of legal consciousness

The survey findings demonstrate the relational nature of legal consciousness: welfare clients' (critical) legal consciousness is shaped by their views on the (harsh and cold) way that welfare officials understand and apply the law. This confirms the key-findings from earlier qualitative research (Reference AkogluAbrego, 2019; Reference AbregoHeadworth, 2020; Reference HeadworthWang, 2019; Reference WangYoung, 2014). As Reference YoungAbrego (2019, p. 644) writes, “individuals do not acquire legal consciousness in a vacuum; rather, they do so as members of social networks and in relation to how others in their social groups experience the law.” In addition, the survey allows us to study the relationship between clients' own legal consciousness and their assessment of welfare officials' legal consciousness in more detail. The correlation analysis shows that clients' assessment of welfare officials' collective legal consciousness is not only related to their own “worldview” and their “perception,” but also to their “decision” (Table 2). In other words, there is not only a relationship between clients' assessment of officials' beliefs about the law and the way in which clients experience and understand the law, but also with the way they act in relation to the law.

Furthermore, the correlation analysis suggests that certain elements of clients' legal consciousness are more relationally influenced than others (Table 2). Generally speaking, clients' legal consciousness mirrors their assessment of welfare officials' collective legal consciousness. Although there are some exceptions to this general rule, it appears that clients' “worldview” and “perception” mostly correlate with their understanding of welfare officials' “worldview” and “perception,” while clients' “decision” mostly correlates with their understanding of welfare officials' “decision.” In other words, the way in which clients experience and understand the law seems to be mostly related to how they think that welfare officials experience and understand the law, while the way in which clients act in relation to law is mostly related to how they think welfare officials will act in relation to law.

The correlation matrix in Table 2 also suggests that clients' self-reported compliance behavior is less relationally influenced than other elements of their legal consciousness. This holds true for their overall compliance, their compliance with the obligation to report extra income, and their compliance with the obligation to apply for a job (Table 2). None of these elements correlates with their perceptions of welfare officials' legal consciousness (except the probability of sanction). Table 2 also shows a remarkable contrast between clients' overall compliance and their intended future compliance. Focusing on all relations between 0.2 and 0.4, clients' overall compliance is related to almost no aspect of their understanding of welfare officials' beliefs about the law (except the probability of sanction); while clients' intended future compliance is related to nearly all aspects of welfare officials' legal consciousness (except the perceived level of punitive enforcement).

One possible explanation for this finding is that clients' compliance behavior is mostly determined by other, more urgent, factors. This echoes Reference AbregoGustafson's (2011, p. 93) finding that welfare clients sometimes lived without the rules “because their economic or family needs outweighed their compliance with the rules.” This does not mean that their assessment of welfare officials' legal consciousness is completely irrelevant; but rather that these other considerations are more relevant. This may also explain why welfare clients' level of overall compliance is mostly related to the perceived probability of sanction. For most clients, the fear of a heavy fine or a reduction in their benefits may be a more important driver for their behavior then other elements of welfare officials' legal consciousness. This could also help to explain the remarkable contrast between Dutch welfare clients' overall compliance and their intended future compliance. When asked about the future, clients may focus less on the immediate needs and pressures of their everyday lives. In this scenario, in which the role of (welfare) law becomes more abstract, the correlation matrix suggests that clients' perceptions of welfare officials' legal consciousness are directly related to their future compliance and the probability of sanctions becomes (somewhat) less important.

Negative cycle of relational legal consciousness

In Reference GustafsonHeadworth's (2020, p. 347) study of welfare fraud officials and welfare clients in the US, their legal consciousness is constantly shaped in an “iterative process of social exchange through which different actors' attempts to “read one another's minds” help produce lived legal realities” (Reference HeadworthHeadworth, 2020, p. 324). This cycle of relational legal consciousness can also be observed in our study.

Most Dutch welfare clients feel that people should obey the law even if it goes against what they think is right. They also expect that this position towards the law will be reflected in their interactions with welfare officials. However, rather than the positive attitude they were expecting, clients reported that welfare officials often treat them with a great deal of suspicion. In their view, welfare officials see all clients as potential fraudsters and therefore mostly emphasize which sanctions will follow if clients break the rules. This echoes Gustafson's earlier study who found that “welfare rules assume the criminality of the poor” (Reference HeadworthGustafson, 2011, p. 1) and Reference GustafsonHeadworth's (2020, p. 329) finding that welfare fraud enforcement workers view clients with “suspicion and distrust.” Some welfare officials would probably argue that, by treating each client as a potential criminal, the chances of discovering fraud are much higher. Moreover, if they find no proof of any wrongdoing, their client is free to go without any further consequences. Or, as they may put it: “No harm, no foul.” However, in practice this approach is not without problems. Welfare clients are often surprised, offended and frustrated that—despite their good will—they are still treated as potential fraudsters. As two of them explain (in the open fields of the survey):

“I expected that [the welfare office] would be much more helpful and that they would act less like a grumpy policeman.”

“They made me feel like a parasite, while I would love to work again.”

It seems likely that this perceived mismatch between their own compliance behavior and the response by welfare officials is also reflected in their evaluation of the welfare office. For example, as we saw earlier, only a small group (17.8%) of welfare clients say that the welfare office acts in the interest of benefits recipients and some people (19.3%) even feel that the welfare office abuses the vulnerable position of welfare clients. Also, most clients experience very little procedural justice. Only one third (31.4%) of respondents feel that welfare clients are treated fairly by their welfare office and a similar small percentage (32.1%) feel that their welfare office allows welfare clients to tell their side of the story. Finally, more than one-third of respondents (36%) indicate that their level of trust in government has fallen after contact with the welfare office. There are some indications that these negative experiences of welfare clients may also be associated with less compliance. For example, Table 2 shows that there is no significant positive correlation between a punitive enforcement style and clients' intended future compliance (r s = −0.058), while there is a (moderate/strong) positive correlation between clients' intended future compliance and the perceived legitimacy of the welfare office (r s = 0.433), the perceived level of procedural justice (r s = 0.400) and the perceived level of persuasive enforcement (r s = 0.380). Conversely, any negative changes in these three variables may be associated with negative changes in clients' future compliance behavior.

When confronted with less compliance, welfare officials will probably respond with further sanctions. For welfare clients, this could be a reason to question the legitimacy of welfare law even more, and so on. This “on-going back-and-forth between each side's assessment of the other” (Reference HeadworthHeadworth, 2020, p. 347) may result in a negative cycle of relational legal consciousness. This refers to an iterative process of social exchange in which the negative treatment of welfare clients as latent criminals has a negative effect on clients' legal consciousness and their future compliance behavior. When this happens, the punitive enforcement style of Dutch welfare officials (which lawmakers often promote as the most effective remedy for rule violations) could ultimately result in less rather than more compliance. Additional research (using a regression analysis) is needed to test this hypothesis.

Limitations of this study

There are several limitations to the approach of this study. All measures rely on self-reports, which may be susceptible to social desirability bias (Van de Reference HeadworthMortel, 2008). It should be noted, however, that the levels of compliance with welfare obligations in this study are in line with objective measures during this period (Reference Van de MortelSZW, 2010; Van Gils et al., 2007). Moreover, a similar level of support for the law in general is also reflected in other qualitative research (Reference Van Gils, Frank and Van der HeijdenGustafson, 2011, pp. 148–151).

This study has used several “proxy measures” to analyze welfare clients' assessment of welfare officials' legal consciousness. These survey items give us a good first indication of clients' understanding of officials' collective beliefs about the law. However, in order to get a more detailed and more precise view, future studies should also try to develop items that ask clients more directly about their perceptions of the ways in which officials experience, understand, and act in relation to law. This future research may benefit from some of the findings of the present study. The survey also raises some questions about the level of analysis and the “notion of relational” (Reference GustafsonYoung, 2014, p. 526). When completing the survey, some clients may be thinking about the law in general (macro), while other questions are more related to their local welfare office (meso) or even to an individual welfare official (micro). Further research (using quantitative and qualitative methods) could further deepen our understanding of these different and interrelated layers of people's legal consciousness.

Finally, because this exploratory study is first and foremost interested in the relationship between two variables and its primary interest is not the effect of one (or more) variable(s) on another (dependent) variable, I chose to focus on a correlation analysis and not to run a regression analysis (Reference Youngle Cessie et al., 2021). A correlation matrix is useful to summarize a large amount of data and to see patterns in the relationship between variables. These findings can help us to identify possible inputs for a future regression analysis. However, some limitations to the correlation matrix should be noted as well. Most (relevant) correlation coefficients in this study were between 0.2 and 0.4, indicating a weak to moderate/strong relationship between welfare clients' own legal consciousness and clients' assessment of welfare officials' legal consciousness. There were no coefficients 0.5 or higher, which would indicate a strong or very strong relationship between both variables (Reference le Cessie, Groenwold and DekkersAkoglu, 2018). This suggests that, although clients' assessment of welfare officials' collective beliefs about the law is relevant for the development of their own legal consciousness, other variables (that were not included in this study) may be even more important. Other studies point to the relevance of, for example, general legal knowledge and legal literacy (see, e.g., Reference AkogluCrawford & Bull, 2006; Reference Crawford and BullPreston-Shoot & McKimm, 2013; Reference Preston-Shoot and McKimmHorák et al., 2021). Also, in a correlation matrix there may not only be a relationship between the variables on the horizontal and the vertical axis, but some of the variables on each axis may be interrelated as well. Further research (using a regression analysis) is needed to study this in more detail.

CONCLUSION

Writing more than three decades ago, Reference Horák, Lacko and KlocekSarat (1990, p. 378) observed that “the welfare poor create a consciousness of law” not only on the basis of their daily deprivation, but also based on “their experience of unequal often demeaning treatment, and their search for tools with which to cope with an often unresponsive welfare bureaucracy.” The present study confirms the relational nature of legal consciousness from Sarat's early research and from other more recent qualitative studies. Although Dutch welfare clients are supportive of the law in general, they also criticize the legitimacy of welfare law. In their view, the central feature of welfare officials' legal consciousness is the mechanical application of rules without regard for the fairness of the results. The correlation matrix shows that both dimensions are closely interlinked: welfare clients' (critical) legal consciousness is shaped by their views on the (harsh and cold) way that welfare officials apply the law. Reference SaratChua and Engel (2019, p. 349) have suggested that increased attention to relational legal consciousness has the potential to lead to the formulation of “new questions, new research designs, and theories about when and how law becomes active.” The current study makes three contributions to the literature.

Firstly, this study adds to our empirical knowledge of relational and second-order legal consciousness. While earlier research on welfare law and legal consciousness often looked at the role of the welfare official (Reference Chua and EngelHeadworth, 2020), this study focuses on the other side of this relationship: the position of the welfare client. When combined, these studies provide us with a more complete account of the interplay between officials and clients and the way in which this affects their legal consciousness.

Secondly, this study adds to our theoretical understanding of the mechanisms that contribute to the production of relational and second-order legal consciousness. The survey findings suggest that that certain aspects of welfare clients' legal consciousness are more relationally influenced than others and that certain aspects of the way that they perceive others' legal consciousness are more influential than others. Moreover, this study suggests that clients' self-reported compliance behavior is less relationally influenced than other elements of their legal consciousness. One direction for future research may be how legal consciousness shapes legal compliance. This issue is not only addressed in legal consciousness studies, but it is also the central focus in an extensive body of literature on legitimacy (see, e.g., Reference HeadworthTyler, 1990; Reference TylerJackson et al., 2012; Reference Jackson, Bradford, Hough, Myhill, Quinton and TylerWalters & Bolger, 2019). Although legal consciousness can be understood “as one of the core elements of the legitimacy of any legal system” (Reference Walters and BolgerHorák et al., 2021, p. 9; Reference Horák, Lacko and KlocekJenness & Calavita, 2018; Reference Jenness and CalavitaYoung, 2014), both types of studies usually do not speak to each other. It would be useful, therefore, to look for ways to bridge both literatures. Future studies could also test our hypothesis that—due to a negative cycle of relational legal consciousness—treating welfare clients as latent criminals will ultimately result in less rather than more compliance.

Finally, the present study is based on a survey among welfare clients. In earlier studies, semi-structured interviews and observations were instrumental to gain better insight in relational legal consciousness and to formulate hypotheses for future research. The survey made it possible to test some of these hypotheses. Also, a correlation analysis allowed us to analyze the relationship between welfare clients' own legal consciousness and their second-order consciousness in more detail. However, correlation does not imply causation. Additional research is needed to establish which aspects of clients' assessment of welfare officials' beliefs (and which possible other variables) may cause changes in their own legal consciousness (and vice versa). Moreover, studying the strengths and weaknesses of qualitative and quantitative methods advances the debate on what future methodologies might look like and how key concepts might be operationalized.

Taken together, the empirical, theoretical and methodological findings from this study contribute to our understanding of the interactive production of welfare clients' legal consciousness in a punitive welfare state.

Survey questions and items.

Perceived obligation to obey the law: Footnote 8

(M = 3.53; SD = 0.53; Cronbach's α = 0.80)

(Completely disagree–completely agree; scaled 1–4)

• People should obey the law even if it goes against what they think is right.

• Disobeying the law is almost never justified.

• I always try to obey the law, even if I do not agree with it.

Support for the obligation to report extra income:

(M = 2.75; SD = 0.85; Cronbach's α = 0.66)

(Completely disagree–completely agree; scaled 1–5)

• In my view, not reporting income from chores is benefit fraud.

• I do not think that you have to declare all income to the welfare office (R). Footnote 9

• I have no problem with the fact that the welfare office can request my income.

Support for the obligation to apply for a job:

(M = 3.54; SD = 0.75; Cronbach's α = 0.61)

(Completely disagree–completely agree; scaled 1–5)

• I find it ridiculous that it is determined for me how much I should apply for a job (R).

• I think it is right that over time you should accept all jobs.

• People who do not do their best to find a job should be cut back on their benefits.

Overall compliance:

(M = 4.11; SD = 0.62; Cronbach's α = 0.78)

(Completely disagree–completely agree; scaled 1–5)

• I pass on as much information as possible to the welfare office.

• I do my best to comply with the welfare benefits rules.

• I honor the agreements with my welfare office as much as possible.

Compliance with the obligation to report extra income:

(M = 3.68; SD = 0.76; Cronbach's α = 0.61)

(Completely disagree–completely agree; scaled 1–5)

• If I do paid chores for friends, I report this to the welfare office.

• If I occasionally get paid in cash for work, I do not report this to welfare office.

• I always report all income to the welfare office.

Compliance with the obligation to apply for a job:

(M = 3.27; SD = 0.76; Cronbach's α = 0.53)

(Completely disagree–completely agree; scaled 1–5)

• I do my best to find a job as soon as possible.

• I do not apply for a job more than necessary (R).

• I accept all the work that is offered to me.

Intended future compliance: Footnote 10

(M = 3.54; SD = 0.67; Cronbach's α = 0.72)

(Completely disagree–completely agree; scaled 1–5)

• From now on, I will do what the welfare office asks of me.

• I do not care about the welfare office anymore (R).

• From now on, I will do my best to cooperate with the welfare office.

Legitimacy of the welfare office:

(M = 3.07; SD = 0.74; Cronbach's α = 0.77)

(Completely disagree–completely agree; scaled 1–5)

• How much do you trust the welfare office?

• The welfare office abuses vulnerable people (R).

• The welfare office acts in the interest of benefit recipients.

• The welfare office fulfills its commitments to benefit recipients.

Procedural justice: Footnote 11

(M = 3.10; SD = 0.77; Cronbach's α = 0.85)

(Completely disagree–completely agree; scaled 1–5)

• The welfare office treats welfare recipients fairly.

• The welfare office treats people with respect.

• The welfare office honors its commitments.

• The welfare office explains why certain decisions are taken.

• The welfare office gives people little chance to tell their side of the story (R).

Punitive enforcement: Footnote 12

(M = 3.51; SD = 0.91; Cronbach's α = 0.91)

(Completely disagree–completely agree; scaled 1–5)

• The welfare office is like a policeman; they punish me if I do not comply with the rules.

• The welfare office puts me under pressure to look for a job.

• The welfare office threatens with punishment if I do not apply for a job.

Persuasive enforcement: Footnote 13

(M = 3.01; SD = 0.86; Cronbach's α = 0.83)

(Completely disagree–completely agree; scaled 1–5)

• The welfare office is like a coach; they help me to comply with the rules and to find a job.

• The welfare office is like a teacher; they explain the welfare benefits rules.

• The welfare office explains well what is expected of me.

• The welfare office encourages me to look for a job.

• The welfare office gives good tips to get a job quickly.

Probability of sanction:

(M = 3.89; SD = 0.62; Cronbach's α = 0.77)

(Completely disagree–completely agree; scaled 1–5)

• I think there is a good chance that the welfare office checks whether I comply with the rules.

• I think that the welfare office will find out if I do not look for a job.

• I think that the welfare office will find out if I do not declare my income.

• If the welfare office finds out that someone does not comply with the rules, the chance of a fine is high.

Operationalization of welfare clients' legal consciousness and welfare clients' assessment of welfare officials' legal consciousness. Footnote 14

Welfare clients' legal consciousness:

Welfare clients' assessment of welfare officials' legal consciousness: