INTRODUCTION

As part of the judicialization of international relations (Reference Alter, Hafner-Burton and HelferAlter et al., 2019), states have increasingly created international courts to uphold state accountability for international human rights violations. Starting in the mid-twentieth century, states progressively established four international courts with human rights jurisdictions in Europe (European Court of Human Rights), the Americas (Inter-American Court of Human Rights), Africa (African Court on Human and Peoples' Rights), and West Africa (Community Court of Justice of the Economic Community of West African States or ECOWAS CourtFootnote 1). “International human rights courts” (IHRCs) adjudicate whether states have violated human rights and issue legally binding rulings, including remedies for victims. NGOs have been strong advocates driving this judicialization trend, considering IHRCs provide distinct opportunities for their advocacy. NGOs can use international litigation to achieve human rights change within states, such as when governments comply with international court rulings or pre-emptively change their practices in anticipation of international court intervention. NGOs' litigation can significantly contribute to the expansion of these courts' authority and impacts (Reference Alter, Helfer and MadsenAlteret al., 2016b, p. 24).

However, state backlash against international courts (Reference Alter, Gathii and HelferAlter et al., 2016a; Reference Brett and GisselBrett & Gissel, 2020; Reference Madsen, Cebulak and WiebuschMadsen et al., 2018; Reference VoetenVoeten, 2020), particularly IHRCs (Reference Gonzalez-Ocantos and SandholtzGonzalez-Ocantos & Sandholtz, 2022; Reference HillebrechtHillebrecht, 2021; Reference MadsenMadsen, 2020; Reference Sandholtz, Bei, Caldwell, Brysk and StohlSandholtz et al., 2018; Reference Stiansen and VoetenStiansen & Voeten, 2020), can threaten this potential NGO advocacy forum. Generally, backlash includes a range of extraordinary tactics, reaching the level of mainstream public discourse, that pursue the retrograde objective of returning to a prior condition (Reference Alter and ZürnAlter & Zürn, 2020, pp. 564–8). Specifically with international courts, state backlash targets a court's general authority or authority over a particular state (Reference VoetenVoeten, 2020, pp. 408–9), with tactics that go beyond “the rules of the game” (Reference MadsenMadsen, 2020, p. 730) and resist international courts as institutions (Reference Madsen, Cebulak and WiebuschMadsen et al., 2018, p. 199). State backlash could involve persistent noncooperation and noncompliance with international court decisions (Reference HillebrechtHillebrecht, 2021, p. 21; Reference Sandholtz, Bei, Caldwell, Brysk and StohlSandholtz et al., 2018, p. 160). States may also use more extreme measures, such as regressively reforming the court, withdrawing from its authority, or shutting it down (Reference Alter, Gathii and HelferAlter et al., 2016a; Reference Sandholtz, Bei, Caldwell, Brysk and StohlSandholtz et al., 2018, p. 159). NGOs must navigate the risk or reality of state backlash against IHRCs when determining their human rights advocacy strategies.

States with all regime types, even liberal democracies (e.g., Reference Stiansen and VoetenStiansen & Voeten, 2020), have pursued international-level backlash against IHRCs. But there is an important subset of states, notably those with authoritarian, hybrid, and democratically backsliding regimes, that “shrink” or “close” domestic civic space for NGOs and other civil society actors (Reference Bakke, Mitchell and SmidtBakke et al., 2020; Reference BuyseBuyse, 2018; Reference Dupuy, Fransen and PrakashDupuy et al., 2021; Reference Toepler, Zimmer, Frohlich and ObuchToepler et al., 2020). States can openly use legal and extralegal tactics, such as intimidation, arrests, regulatory restrictions, violence, and other state measures, to repress and reverse NGOs' and other civil society actors' human rights monitoring and advocacy efforts (Reference Bakke, Mitchell and SmidtBakke et al., 2020; Reference BuyseBuyse, 2018). States thus can also engage in domestic-level backlash against human rights accountability. Considered together, these trends reveal that state backlash against human rights accountability can occur at two levels, where states pursue regressive and extraordinary measures against human rights accountability within both the domestic and international spheres.

How does state backlash against human rights accountability, which may occur at the domestic and/or international levels, influence whether and how NGOs use international courts for their human rights advocacy? We develop a new two-level framework for explaining how specific forms of state backlash against human rights accountability can influence whether and how NGOs strategically litigate at IHRCs. We combine insights from the scholarship on legal mobilization for litigation and NGO advocacy to theorize the mechanisms through which state backlash tactics at the domestic and international levels impact NGOs' advocacy and international litigation strategies before IHRCs. Ultimately, the framework highlights how state backlash can both promote and deter NGOs' strategic litigation at IHRCs. This framework notably departs from existing two-level approaches that analyze both domestic and international factors to understand states' international-level backlash against international courts (e.g., Reference HillebrechtHillebrecht, 2021; Reference MadsenMadsen, 2020), where state backlash is the outcome of interest. Our framework focuses on the potential for backlash at two levels (domestic and international) and its consequences for NGOs, as key human rights defenders and IHRC constituencies.

To demonstrate the framework's explanatory value, we empirically analyze the impact of Tanzania's two-level backlash tactics on NGOs' mobilization at the African Court on Human and Peoples' Rights (African Court). Drawing on original quantitative and qualitative data, we provide an overview of cases of NGO participation in litigation against Tanzania at the African Court. From this, we select three cases of NGO-led litigation (concerning the death penalty, the rights of persons with albinism (PWA), and the rights of pregnant schoolgirls and mothers), and process-trace how Tanzania's two-level backlash tactics affected whether and how NGOs mobilized before the African Court. Our analysis aligns with our theoretical expectations that state backlash tactics at the two levels, and interactions between them, can both promote and deter NGO litigation at an IHRC.

This analysis makes several contributions. Conceptually, two-level backlash—distinct from general two-level political approaches—connects backlash phenomena at the domestic and international levels that existing approaches tend to analyze separately. It captures how states, especially authoritarian, hybrid, and democratically backsliding regimes, may resist diverse forms of human rights accountability at different levels of governance. Theoretically, our framework explains the consequences (rather than the causes) of state backlash, focusing on its implications for NGOs as important IHRC constituencies, and it advances research agendas on legal mobilization before international courts and how state behavior influences human rights actors, including NGOs and IHRCs.

Empirically, we provide an unprecedented quantitative and qualitative analysis of the African Court, which is typically excluded from analyses of IHRCs that overwhelmingly focus on the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) and Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR) (e.g., Reference HaddadHaddad, 2018; Reference Hillebrecht, Brysk and StohlHillebrecht, 2019, Reference Hillebrecht2021; Reference Sandholtz, Bei, Caldwell, Brysk and StohlSandholtz et al., 2018). Existing literature on the African Court's cases primarily analyzes its jurisprudence. Even among the exceptions to this trend in the scholarship, our focus on NGO mobilization and interdisciplinary approach is novel. Reference Daly and WiebuschDaly and Wiebusch (2018) and Reference AdjolohounAdjolohoun (2020) have described Tanzania's international-level backlash against the African Court, but have not considered how this co-existed with domestic-level backlash, nor the impacts of Tanzania's two-level backlash. Reference Gathii, Mwangi and GathiiGathii and Mwangi's (2020) pathbreaking analysis of African Court litigation focuses on select cases brought by individuals (opposition politicians and criminal defendants with fair trial claims), not NGOs as such. Reference De Silva, Squatrito, Young, Ulfstein and FøllesdalDe Silva (2018) shows how the African Court's outreach aimed to mobilize NGOs, but does not study whether and how NGOs have mobilized at the Court. While our analysis fills important research gaps on the African Court, it also yields insights for other IHRCs (and potentially other international courts with private actor access), given their similar characteristics and roles for NGOs.

This article proceeds in three stages. First, we develop our framework for explaining how two-level state backlash against human rights accountability influences whether and how NGOs pursue human rights change via IHRCs. We then present our empirical analysis of NGO mobilization against Tanzania at the African Court and our three case studies that process-trace how Tanzania's two-level backlash tactics influenced NGO mobilization. The final sections draw out the implications of our analysis for understandings of state backlash and NGOs' roles in IHRCs.

NGO MOBILIZATION AT INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS COURTS

Strategic litigation at IHRCs—litigation that pursues broader goals than those of the immediate parties (Reference DuffyDuffy, 2018, p. 3)—is a key means through which NGOs can pursue their advocacy for human rights change (Reference HondoraHondora, 2018, p. 115). Strategic litigation at an IHRC can be a means of advancing various human rights advocacy goals, including reforming the justice system of the state, achieving justice for affected individuals or groups, shaming the state before an international forum, establishing facts, or expanding an IHRC's jurisprudence more generally (Reference SundstromSundstrom, 2014, pp. 865–6). For strategic litigation, NGOs can act individually or collaborate with like-minded NGOs, cause lawyers, and other actors within transnational advocacy networks (Reference Keck and SikkinkKeck & Sikkink, 1998) or transnational litigation networks (Reference NovakNovak, 2020).

NGOs can leverage their access, expertise, and resources to directly and indirectly participate in strategic litigation at IHRCs. These courts' formal rules and procedures determine NGOs' potential for direct participation in litigation as applicants themselves and/or as legal representation for individual applicants. NGOs' ability to directly participate in litigation varies across IHRCs, whose access rules broadly follow two models. At the ECtHR, ECOWAS Court, and African Court (when states deposit declarations under Article 34(6) of the Court's Protocol), NGOs—as applicants themselves or as legal representation for individual applicants—can directly petition the IHRC and participate in litigation. In the IACtHR and African Court (when states do not make Article 34(6) declarations), NGOs cannot directly petition the Courts, but can petition a Commission that may forward the case to its respective Court, giving the NGO direct access to litigation. NGOs can also indirectly participate in litigation through advising and capacity-building (e.g., providing training and resources) for the actors directly participating in litigation (e.g., individuals, lawyers). NGOs often indirectly participate in litigation at IHRCs as amicus curiae (Reference CichowskiCichowski, 2016; Reference HondoraHondora, 2018, p. 125), submitting their legal perspectives on cases to align judicial decision-making with their human rights agendas. Given these potential forms of direct and indirect NGO participation in litigation at IHRCs, what explains whether and how NGOs use IHRCs in their human rights advocacy strategies?

One strand of interdisciplinary scholarship in law and the social sciences explains strategic litigation at domestic and international courts based on legal opportunity structures. Potential litigants evaluate the benefits of using political opportunity structures, such as elections and access to the policy-making process (Reference Alter and VargasAlter & Vargas, 2000, p. 477), versus legal opportunity structures (e.g., courts) for advancing their desired change. Courts' institutional features—including rules on access and legal standing, and jurisprudence (or “legal stock”)—determine actors' incentives to strategically litigate to advance their causes (Reference VanhalaVanhala, 2018, pp. 384–5).

Another strand of the scholarship goes beyond legal opportunity structures and focuses on diverse phenomena referred to as “legal mobilization” (see Reference Lehoucq and TaylorLehoucq & Taylor, 2020). Legal mobilization involves broader processes of legal rights-claiming and litigating to defend or develop those rights (Reference EppEpp, 1998, p. 18). Litigation is not the only form of legal mobilization; it exists alongside other means of mobilizing the law for change (Reference McCann, Caldeira, Kelemen and WhittingtonMcCann, 2008, p. 524; Reference VanhalaVanhala, 2012, p. 529), such as advocacy for the implementation of court rulings (Reference SundstromSundstrom, 2012). To explain actors' use of strategic litigation, the legal mobilization perspective stresses the insufficiency of merely analyzing courts' institutional features (i.e., the legal opportunity structure); one must also consider the complex determinants of actors' capacities and goals.

Whether and how actors litigate can be influenced by their legal consciousness (Reference Lehoucq and TaylorLehoucq & Taylor, 2020, pp. 180–1; Reference McCann, Caldeira, Kelemen and WhittingtonMcCann, 2008, p. 529), expertise and experience in litigation (e.g., as “repeat players”) (Reference CichowskiCichowski, 2016; Reference GalanterGalanter, 1974), resources (Reference CichowskiCichowski, 2016), operational safety (Reference MoustafaMoustafa, 2014), networks (Reference ConantConant, 2016), and roles and identities (Reference VanhalaVanhala, 2012). These factors contribute to actors' variable capacities to mobilize around legal opportunities. Actors' goals for litigation are also diverse, where they may seek benefits beyond what a legal opportunity structure is designed to provide. Their strategic litigation can (Reference SundstromSundstrom, 2012), but does not necessarily (Reference McCannMcCann, 1994), aim for a favorable judgment that is met with compliance. For example, actors may litigate to “credibly highlight the failings of the existing systems” (Reference VanhalaVanhala, 2012, p. 525), without the expectation of compliance. Actors, therefore, may pursue litigation despite “relatively hostile legal opportunity structure[s]” (Reference VanhalaVanhala, 2012, p. 524). The legal mobilization perspective, therefore, can elucidate broad determinants of NGOs' direct and indirect participation in strategic litigation at IHRCs, considering how NGOs' diverse capacities and goals interact with the legal opportunities IHRCs provide.

EXPLAINING NGO MOBILIZATION IN THE CONTEXT OF TWO-LEVEL STATE BACKLASH AGAINST HUMAN RIGHTS ACCOUNTABILITY

We argue that state backlash against human rights accountability at the domestic and/or international levels interacts with these diverse domestic- and international-level determinants of NGO mobilization for strategic litigation at IHRCs. Our integrated, two-level approach to state backlash and its potential impact on NGO litigation at IHRCs moves beyond existing studies that tend to focus on either international- or domestic-level backlash, and typically aim to explain state backlash rather than its impacts on potential litigants.

The scholarship on international-level backlash against IHRCs (Reference Gonzalez-Ocantos and SandholtzGonzalez-Ocantos & Sandholtz, 2022; Reference HillebrechtHillebrecht, 2021; Reference MadsenMadsen, 2020; Reference Sandholtz, Bei, Caldwell, Brysk and StohlSandholtz et al., 2018; Reference Stiansen and VoetenStiansen & Voeten, 2020) examines how state backlash tactics constrain international courts' authority and legal opportunity structures (e.g., jurisdiction, accessibility). It focuses on how this international-level state backlash influences courts, rather than its impact on actors that may use these courts. This is a significant omission, particularly considering state backlash measures can seek to narrow the accessibility of IHRCs' opportunities for such users (Reference Sandholtz, Bei, Caldwell, Brysk and StohlSandholtz et al., 2018, p. 160). The legal mobilization perspective also invites us to consider diverse determinants and forms of mobilization around such shifting opportunities at an IHRC.

Another strand of scholarship analyzes how states' domestic-level backlash against human rights accountability within authoritarian or hybrid regimes impacts potential litigants. Some scholars analyze how domestic repression can promote litigation domestically and internationally to counter it (Reference van der Vetvan der Vet, 2018), at least in its initial stages (Reference Hillebrecht, Brysk and StohlHillebrecht, 2019, pp. 166–8). State backlash against NGOs (e.g., foreign funding limitations, and organizational and operational barriers) may also undermine NGOs' capacity to litigate, reducing the number and quality of cases they pursue (Reference Hillebrecht, Brysk and StohlHillebrecht, 2019, pp. 168–70). This scholarship, however, does not link domestic- and international-level backlash, missing how NGOs can face “shrinking space” from these two levels.

We argue, drawing on these distinct strands of scholarship, for a more integrated, two-level framework for explaining the influence of state backlash against human rights accountability on NGO mobilization at IHRCs. This two-level approach recognizes that states can pursue their overarching objective of regressing to a previous condition and aim to counteract increased human rights accountability through backlash tactics at both the domestic and international levels. States' tactics draw on their domestic authority to impose legal and extra-legal restrictions, and their international authority to revoke their consent to international courts. This backlash may directly target NGOs pursuing human rights change. Equally, it may target other actors and institutions in NGOs' environments, indirectly affecting their strategies. States' two-level backlash tactics can influence not only NGOs' legal opportunity structures—what is institutionally possible—but also NGOs' capacities and goals to mobilize around such legal opportunity structures.

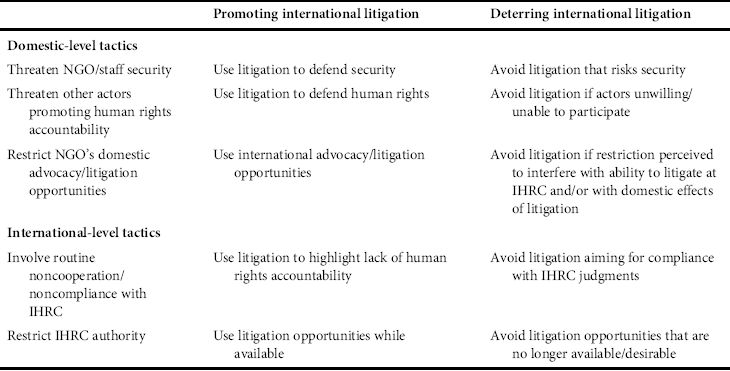

Our theoretical framework (Table 1) shows how various forms of state backlash against human rights accountability at the domestic and international levels can promote and deter NGOs' strategic litigation against that state at an IHRC. The two-level framework addresses the potential for state backlash against human rights accountability to involve tactics at the domestic level, international level, or both simultaneously. The framework applies to NGOs regardless of whether they operate individually or as part of coalitions (e.g., multiple NGOs jointly submitting a case to a court), and whether they operate domestically or internationally (within or beyond the target state, respectively). The framework also applies to all IHRCs, regardless of whether NGOs have direct access to the IHRC or access via a Commission that can forward petitions to the IHRC. For the latter, states' potential international-level backlash against the Commission and/or Court would be considered (Reference Gonzalez-Ocantos and SandholtzGonzalez-Ocantos & Sandholtz, 2022; Reference HillebrechtHillebrecht, 2021, pp. 117–24).

TABLE 1 Potential impacts of two-level state backlash tactics on NGO litigation at IHRCs

Abbreviations: IHRCs, international human rights courts; NGOs, nongovernmental organizations.

The framework delineates how various aspects of states' domestic- and international-level backlash tactics affect NGOs' opportunities, capacities, and goals, and therefore their engagement in litigation at an IHRC. Drawing on diverse scholarship on NGO advocacy, state backlash, and courts, we outline how state backlash tactics can both promote and deter NGO mobilization at an IHRC. How NGOs reconcile the promotional and deterring logics will affect whether they use litigation at an IHRC and how they pursue such litigation (e.g., direct versus indirect participation; individual versus networked litigation). As the legal mobilization perspective emphasizes, NGOs' perceptions of state backlash tactics and their implications will influence whether and how these mechanisms promote and deter litigation. NGOs' variable legal consciousness, expertise, networks, and so on can shape their perceptions and strategies.

States' use of domestic-level legal and extralegal measures to counteract actors and institutions promoting human rights accountability can impact NGOs' advocacy, with the potential to both promote and deter their litigation at an IHRC. States' domestic-level backlash tactics can involve state legislation, regulation, policies, rhetoric, and violence that threaten the security and reduce the capacity of NGOs and their staff (Reference Bakke, Mitchell and SmidtBakke et al., 2020; Reference BuyseBuyse, 2018; Reference Fransen, Dupuy, Hinfelaar and MazumderFransen et al., 2021). These state tactics can make it difficult for NGOs to be registered to operate within a state, gain foreign funding, and so on. As much as NGOs pursue value-driven advocacy goals (Reference Keck and SikkinkKeck & Sikkink, 1998), they also seek to maintain their organizational security, in terms of organizational resources (e.g., funding, staff) and survival (e.g., Reference BobBob, 2002; Reference Cooley and RonCooley & Ron, 2002). Such attacks on NGOs' security and capacity could both promote or deter their litigation at an IHRC. NGOs can continue to litigate under these repressive conditions (e.g., Reference van der Vetvan der Vet, 2018), and if the backlash tactics undermining their security can be framed as violations of human rights—most notably freedom of association, freedom of assembly, and freedom of expression (Reference BuyseBuyse, 2018, pp. 978–82)—they can use human rights advocacy and litigation at an IHRC to defend their security. In this case, NGOs' legal consciousness and expertise would be important. States' domestic-level backlash tactics, however, could also deter NGOs from pursuing human rights advocacy, including litigation at an IHRC, that they would perceive as increasing their vulnerability to state repression (Reference Fransen, Dupuy, Hinfelaar and MazumderFransen et al., 2021, p. 16). Some NGOs may be completely deterred from participating in litigation, but other NGOs may draw on their networks for partners that can take the lead in litigation, while those vulnerable NGOs participate indirectly to evade state detection and possible reprisals.

Similar dynamics can promote and deter NGO litigation when shrinking civic space affects other human rights defenders and civil society actors in ways that are relevant to NGOs' value-driven advocacy goals (e.g., Reference Keck and SikkinkKeck & Sikkink, 1998). This alignment with their missions can mobilize NGOs to advocate against these state backlash-related human rights violations, potentially through litigation at an IHRC (Reference van der Vetvan der Vet, 2018). But state backlash against human rights defenders and other civil society actors can also deter NGO litigation when state backlash renders actors that are essential for NGO litigation strategies unwilling or unable to challenge the state and participate in litigation (Reference Hillebrecht, Brysk and StohlHillebrecht, 2019, p. 167). Like NGOs, as discussed above, these actors may refrain from engaging in advocacy that could increase their vulnerability (Reference Fransen, Dupuy, Hinfelaar and MazumderFransen et al., 2021, p. 16).

Furthermore, states' domestic-level backlash tactics can restrict political and legal opportunities for pursuing state accountability for human rights violations, which can both promote and deter NGOs' litigation at IHRCs. States' extraordinary limitations on political opportunities (e.g., closed policymaking processes) and legal opportunities (e.g., political interference in courts) influence NGOs' advocacy strategies. The closure of domestic advocacy opportunities would generally promote NGOs' international advocacy (Reference Keck and SikkinkKeck & Sikkink, 1998), potentially via international litigation (e.g., Reference Alter and VargasAlter & Vargas, 2000). However, NGOs could be deterred from litigating at an IHRC if they (correctly or incorrectly) perceive the closure of domestic legal opportunities as preventing them from exhausting local remedies (see Reference Hampson, Martin and ViljoenHampson et al., 2018, p. 164), which is a requirement at all IHRCs except the ECOWAS Court. NGOs may also be deterred if they assess that a state's closure of domestic political and legal opportunities would undermine the desired domestic effects of international litigation (e.g., implementation of an IHRC judgment). NGOs' variable legal consciousness and expertise would influence their assessments and strategies.

At the international level, when state backlash against an IHRC occurs, it can shape NGOs' legal opportunities at the IHRC in ways that can both promote and deter their litigation. State backlash through routine noncooperation and noncompliance provides NGOs the opportunity to “credibly highlight” (Reference VanhalaVanhala, 2012, p. 525) the state's failure to accept accountability for human rights violations by litigating at the IHRC. However, when NGOs' advocacy strategies focus on state compliance with an IHRC judgment (see Reference SundstromSundstrom, 2012), this form of state backlash would deter litigation. State backlash tactics can also exploit the consent-based nature of international law and limit the IHRC's authority (and legal opportunities for NGOs) in whole or in part (e.g., withholding judicial appointments to halt court operations, restrictions on jurisdiction or accessibility, complete withdrawals from jurisdiction). Since there may be a delay between the state's use of the backlash tactic and its legal effect (e.g., withdrawals typically taking effect after a one-year delay), the impending closure of the IHRC's legal opportunities can mobilize NGOs—particularly those with legal consciousness and expertise in the IHRC—to litigate while they can. However, this restriction of an IHRC's authority could also deter NGOs from pursuing litigation if the backlash renders litigation opportunities unavailable or undesirable for their advocacy goals. Given the legal complexities of state backlash against IHRCs, NGOs' variable legal consciousness and expertise would strongly affect how they pursue litigation amid this backlash.

Overall, the framework demonstrates the distinct pathways through which state backlash against human rights accountability influences NGOs' opportunities, capacities, and goals, and therefore their mobilization at IHRCs. It focuses on how particular forms of backlash can promote or deter NGOs' litigation before IHRCs. NGOs must navigate these dynamics with their advocacy strategies, but they have variable capacities (e.g., legal consciousness, expertise, networks) to do so. The framework thus elucidates interactions between states, NGOs, and IHRCs, which influence the use and relevance of IHRCs.

DATA AND METHODS

To demonstrate the explanatory value of this theoretical framework, we draw on evidence from Tanzania's two-level backlash against human rights accountability and NGO mobilization against Tanzania at the African Court. Under the Magufuli regime (2015–2021), Tanzania's two-level backlash developed and escalated over time, providing an empirical opportunity to evaluate our framework's various mechanisms. In addition, at the African Court, NGOs could participate both directly and indirectly in litigation against Tanzania, enabling us to explore the influence of our theorized mechanisms on the full range of forms of NGO mobilization at an IHRC.

We first outline Tanzania's two-level backlash against human rights accountability, drawing on secondary literature (e.g., media and NGO reports, academic literature). We identify the state backlash tactics that, according to our framework, NGOs would need to navigate when deciding whether and how to use international litigation for their advocacy. Our empirical analysis of the impact of this two-level backlash on NGOs' mobilization at the African Court follows two steps. First, we develop an overview of NGOs' direct and indirect participation in litigation against Tanzania at the African Court over time. This identifies nine cases of NGO mobilization at the Court that are suitable for process-tracing the framework's mechanisms. For NGO's direct participation, we analyze our original data set of all 155 applications against Tanzania at the African Court (2006–2021), coded from court documentation. To our knowledge, this is the scholarship's first systematically coded data set on applications to the African Court. To capture NGOs' potential indirect participation, we draw on data from expert interviews.

Then, from the nine identified cases of NGO-led strategic litigation against Tanzania at the African Court, we select three cases situated at different points in Tanzania's backlash and thus potentially affected by different backlash tactics. These diverse cases (Reference GerringGerring, 2007, pp. 97–9) capture NGOs' exposure to various backlash tactics at the two levels of our framework. This approach notably focuses on NGOs that did mobilize at the African Court but, as our analysis shows, also captures potential partner NGOs whose mobilization was partially or fully deterred. We use process tracing to evaluate the framework's causal mechanisms (i.e., the pathways through which distinct forms of state backlash promote and deter NGO litigation), while also considering background factors that potentially mediate the relationships we theorize. We draw on data from 10 semi-structured interviews conducted during May–August 2021 with NGO representatives and collaborating lawyers (either legal counsel or co-applicants) that were, or considered being, directly or indirectly involved in each case of strategic litigation. We purposively sampled interviewees based on information on NGO websites and then snowball-sampled further interviewees. For supplementary data, we analyzed NGOs' documentation of their activities (e.g., annual reports, newsletters, press releases), available on their websites. These sources covered, as applicable, NGOs' mobilization surrounding their preparation of an application, engagement in African Court proceedings, and advocacy following African Court decisions, as well as their understanding of and strategic adjustment based on Tanzania's two-level backlash.

TANZANIA'S TWO-LEVEL BACKLASH AGAINST HUMAN RIGHTS ACCOUNTABILITY

Domestic level

The Tanzanian government, led by the Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) party since Tanzania's independence in 1961, had longstanding tensions with civil society actors (Reference HarrisonHarrison, 2018, p. 3). However, in 2015 when John Magufuli became leader of the CCM, the Tanzanian government took “a sharp authoritarian turn” (Reference PagetPaget, 2017, p. 156). Under Magufuli's rule, there was a swift and escalating domestic-level backlash against human rights accountability. The government restricted civic space and demonstrated “more overt hostility” to civil society actors such as human rights NGOs (Reference HarrisonHarrison, 2018, p. 3). The government's backlash tactics were widely reported and cause for concern among NGOs (e.g., CSO Directors, 2018, p. 1).

The government initially focused on repressing dissent and opposition. The government issued executive orders, legislation, and policies to restrict political opposition, human rights criticism, and protections for human rights such as freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and freedom of assembly (Reference PagetPaget, 2017, p. 156). It also intimidated civil society actors, including NGOs, through arrests, license revocations, and state harassment (Reference PagetPaget, 2017, p. 156). These backlash tactics threatened human rights and the security of human rights defenders, such as NGOs.

The Tanzanian government's domestic-level backlash eventually began focusing on directly restricting NGOs. In 2017, the government conducted a sweeping “mandatory verification of all NGOs,” which gave the government access to information that would facilitate targeting vulnerable NGOs (DefendDefenders, 2018, p. 28). The government also started enforcing existing laws, which had previously been used infrequently (Reference HarrisonHarrison, 2018, p. 15), to limit the scope of operations of NGOs to the “level” (district, regional, national, and international) at which they were registered (Reference HarrisonHarrison, 2018, p. 11). This included restricting domestic NGOs' foreign funding (DefendDefenders, 2018, pp. 20–1). Even when NGOs were not directly targeted, the burden and costs associated with the government regulations and requirements for government approvals of activities severely restricted NGOs' work (Reference HarrisonHarrison, 2018, p. 16).

Government officials' verbal attacks and threats to NGOs working with vulnerable groups and engaging in legal advocacy also became commonplace (ABA, 2018). In April 2018, for example, President Magufuli threatened to close all NGOs perceived as being anti-government or whose work was critical of the government (Reference MushiMushi, 2018), including threats against leading legal NGOs, such as the Tanganyika Law Society (ABA, 2018, pp. 12–9). There were also reports of increased violence against legal advocacy organizations, with some law offices experiencing bombings or break-ins, and lawyers being physically attacked or arbitrarily arrested for representing “unsavory clients” (ABA, 2018, pp. 21–2). These diverse tactics threatened NGOs' organizational security and survival. The Tanzanian government eventually significantly restricted NGOs' domestic litigation opportunities. In June 2020, Tanzania's National Assembly passed an amendment to the Basic Rights and Duties Enforcement Act, requiring anyone seeking legal redress for human rights violations under the Constitution's bill of rights to prove that they are personally affected (OHCHR, 2020).

Under Magufuli's rule (2015–2021), the Tanzanian government thus used all domestic-level backlash tactics theorized in our framework. It used repressive tactics against NGOs, human rights defenders, and other civil society actors, and it restricted domestic advocacy and litigation opportunities. After Magufuli's death in March 2021, the new administration led by former Vice-President Samia Suluhu Hassan signaled some easing of restrictions (e.g., removing bans on media outlets) and increased commitments to human rights (e.g., issuing over 5000 pardons to reduce prison overcrowding) (Human Rights Watch, 2021), but many restrictions on civic space remained.

International level

The Tanzanian government's international-level backlash against human rights accountability, which focused on the African Court, developed more slowly. When the African Court first became operational in 2006, Tanzania, as the Court's host state, cooperated with the Court on various operational matters and was one of the states that most openly supported the Court (Reference De Silva, Hohmann and JoyceDe Silva, 2019). By hosting the Court, Tanzania sought “to be known as the Justice and human rights capital of Africa” (The New Times, 2012). Tanzania also indicated its support for human rights accountability via the African Court by depositing its Article 34 (6) special declaration, allowing individuals and NGOs to submit applications against Tanzania at the Court in 2010.

However, state backlash emerged as the African Court increasingly issued orders for provisional measures, judgments on the merits, and reparations orders against Tanzania. The Court's first judgment against Tanzania in 2013, which was not threatening to the CCM party (Reference Brett and GisselBrett & Gissel, 2020, pp. 128–9), concerned the election-related Mtikila et al. v. Tanzania (2013) case. Tanzania only published the judgment and ignored the other more significant remedies the Court ordered (African Court, 2016, p. 5; African Court, 2017, pp. 8–9). By the mid-2010s, Tanzania was routinely not complying with decisions. In 2017–2018, Tanzania did not report on its implementation of the numerous African Court decisions against it (African Court, 2017, pp. 8–11; African Court, 2018, pp. 12–3; African Court, 2019, pp. 45–50); refused to implement decisions (Reference Daly and WiebuschDaly & Wiebusch, 2018, pp. 306–7; Reference PossiPossi, 2017); or simply indicated it could not or would not implement decisions (African Court, 2020, pp. 18–24). Alongside this routine and overt noncompliance, Tanzanian government officials began openly challenging the Court at the institutional level. They argued it should be more efficient in handling cases, have clearer judgments, and provide “technical assistance and other support” to facilitate state implementation of decisions (Reference QorroQorro, 2018).

Tanzania's backlash escalated with its November 2019 announcement that it was withdrawing its special declaration. Tanzania's notice of withdrawal claimed the declaration had been “implemented contrary to [its] reservations” requiring that individuals and NGOs could only access the African Court “once domestic legal remedies have been exhausted and in adherence with [Tanzania's] Constitution” (African Union, 2019). While what instigated Tanzania's withdrawal announcement is unclear (Reference De Silva and PlagisDe Silva & Plagis, 2020) and seemingly complex (Reference AdjolohounAdjolohoun, 2020, pp. 9–11), the announcement sent a clear signal: individuals and NGOs—the only source of existing applications against Tanzania—would lose their legal opportunities to directly submit applications against Tanzania at the African Court. Based on the Court's previous decision on Rwanda's declaration withdrawal, Tanzania's withdrawal would take effect one year later, which the African Court defined as 22 November 2020 (Andrew Ambrose Cheusi v. Tanzania 2020, paras. 36–9). After President Magufuli's passing, Tanzania's new President Samia Suluhu Hassan confirmed in May 2021 that the government would maintain its position on the withdrawal but may reconsider it in the future (Tanzania Daily News, 2021).

Thus, Tanzania's international-level backlash overlapped with its domestic-level backlash, with backlash at both levels escalating over the course of Magufuli's leadership (2015–2021). This two-level, increasing backlash reflected the Tanzanian government's general rejection of human rights accountability at either level of governance. Based on our theoretical framework, we would expect Tanzania's evolving, two-level backlash against human rights accountability to influence whether and how NGOs participated in strategic litigation against Tanzania at the African Court. We can expect these tactics would influence NGOs' opportunities, capacities, and goals, potentially deterring and promoting NGOs' international litigation according to our framework's mechanisms.

NGO LITIGATION AGAINST TANZANIA AT THE AFRICAN COURT

An overview of NGOs' direct and indirect mobilization at the African Court is a necessary foundation for identifying cases of NGO mobilization that would be subject to, and potentially influenced by, Tanzania's various backlash tactics. Given the absence of existing analyses of NGO litigation at the African Court, we collected and analyzed original data.

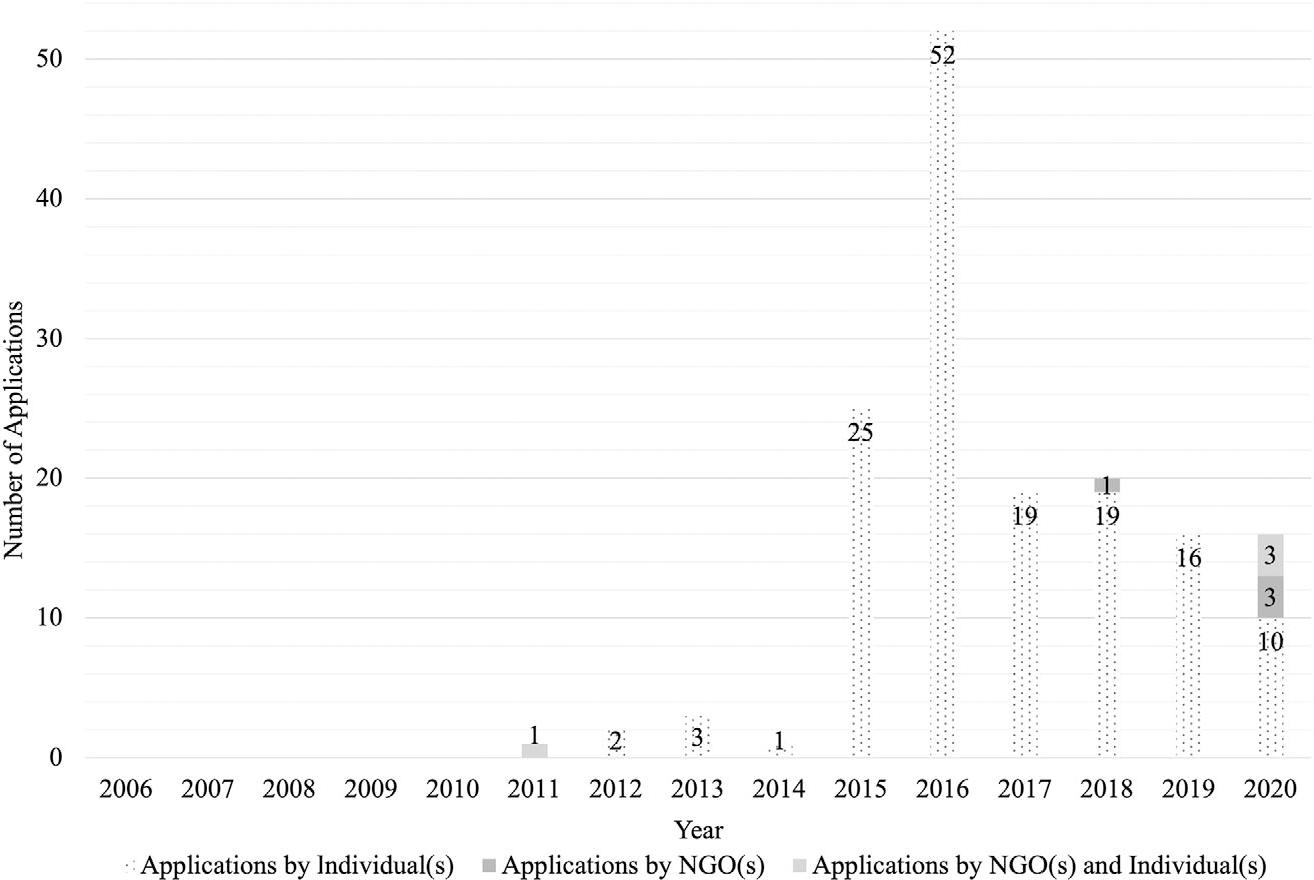

Direct participation

We developed an original data set (see Data S1) on NGOs' direct participation in applications (as applicantsFootnote 2 or legal representation), based on all applications with Tanzania as the respondent state documented on the African Court's website as of May 2021 (African Court, n.d.). The 155Footnote 3 applications were hand-coded for the date of the application, applicant type (e.g., individuals, NGOs), and applicant names. For a subset of 37 applications that were finalized and had greater documentation available, the legal representation of the applicant(s) and the human rights issue(s) raised by the application were also hand-coded.

Figure 1 shows the applications to the African Court against Tanzania over time, starting in 2006 when the Court became operational and Tanzania ratified its Protocol. All applications against Tanzania were filed by individuals and NGOs while Tanzania's special declaration was in effect (2010–2020). There were no inter-State, African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights, or African intergovernmental organization applications, as permitted under Article 5 of the Court's Protocol. Compared to individuals, NGOs' direct participation as applicants was limited overall, accounting for 8 of the 155 applications. Most of these were submitted after Tanzania's declaration withdrawal announcement in November 2019 and before it entered into effect (and NGOs lost direct access) in November 2020. Half the applications with NGOs as listed applicants were registered just days before the declaration withdrawal took effect. While registration dates do not account for the full scope of mobilization and preparation of the applications, NGO applications evidently clustered around this key phase of Tanzania's international-level backlash.

FIGURE 1 Applications against Tanzania at the African Court

Of the eight applications with direct NGO participation, all but one involved multiple, seemingly networked litigants (Table 2). There was an even split between applications exclusively submitted by NGOs and a mix of NGOs and individuals. Applications with NGO-only applicants mostly involved multiple NGOs as listed applicants. A total of six NGOs were listed applicants. The LHRC stood out as a repeat player, as it was an applicant on 7 of 8 NGO applications. These NGOs were diversely situated the domestic level (LHRC, Tanganyika Law Society, Tanzania Human Rights Defenders Coalition), African regional level (CHR, IHRDA), and international level (Equality Now). They were largely legal and human rights-focused NGOs, with only Equality Now (focused on women's rights) being an issue-specific NGO.

TABLE 2 NGOs' direct participation as listed applicants in litigation against Tanzania at the African Court

Note: Bullets are a symbol signifying the presence of either “NGO(s) only” OR “NGO(s) and individuals” for each row of applicants in the table.

Beyond directly participating as listed applicants, there were only limited signs of NGOs' direct participation as legal representation. Our analysis of the 37 applications that could be coded for legal representation revealed a mix of independent lawyers and lawyers affiliated with the Pan African Lawyers Union (PALU) and East Africa Law Society (EALS)—two regional bar associations that are NGOs. With the exception of one application related to freedom of movement, these NGO-affiliated lawyers were always legal representation on applications related to fair trial rights. This may have been coincidental, considering applications concerning fair trial rights represented 32 of the 37 applications we coded for issue(s) raised. Nevertheless, this clustering of NGO-associated legal representation on fair trial applications indicated the potential for a broader, and perhaps more indirect, form of NGO mobilization and involvement in litigation in this area.

Indirect participation

We relied on expert interviews to capture indirect NGO participation (e.g., capacity-building, advising) in litigation against Tanzania at the African Court, as there is no relevant documentation systematically available from the African Court or other sources. We interviewed a senior official from the NGO Coalition for an Effective African Court (ACC) and the founder and director of the ACtHPR Monitor website, Oliver Windridge. These are the two monitoring bodies that exclusively focus on the African Court and thus have extensive informal knowledge of mobilization around the Court. Since 2003, the ACC has served as an umbrella organization for a network of African NGOs and civil society actors that support the African Court (ACC, 2021). It often directly engages African NGOs and lawyers in its general trainings on litigation at the African Court (ACC, 2021). Since 2014, the ACtHPR Monitor website has provided analysis of the African Court for a global audience, leading various international actors to regularly consult Windridge for guidance on the Court and its opportunities for litigation (Reference WindridgeWindridge, 2021).

While the ACC official was only aware of direct, not indirect, NGO participation, particularly as Tanzania's declaration withdrawal was about to take effect (ACC, 2021), Reference WindridgeWindridge (2021) identified one NGO that was indirectly participating in litigation against Tanzania at the African Court. Reprieve UK, an international NGO advocating against the death penalty, had for many years been active in fair trial cases against Tanzania brought by prisoners on death row—a cluster of cases that accounts for a significant proportion of litigation against Tanzania at the African Court. Reference WindridgeWindridge (2021) reported that Reprieve had visited a prison from which many pro se applications—filed by applicants on their own behalf—emerged. Our analysis, therefore, revealed both direct and indirect NGO participation in litigation against Tanzania at the African Court, most of which coincided with Tanzania's two-level backlash against human rights accountability.

CASE STUDIES

Overall, we identified a total of nine cases of NGO-led strategic litigation against Tanzania at the African Court: eight cases of NGO mobilization to submit particular applications (Table 2) and one case of NGO mobilization for multiple applications focused on a single human rights advocacy issue. From these, we selected three diverse cases (Reference GerringGerring, 2007, pp. 97–9) that, judging from their application registration dates, capture NGOs' international litigation in the context of Tanzania's various backlash tactics. In our first case, Reprieve UK's mobilization against the death penalty in Tanzania appeared to occur in the mid-2010s, during the emergence of Tanzania's domestic- and international-level backlash. In our second case, CHR, IHRDA, and LHRC submitted their application regarding PWA in 2018, when Tanzania's backlash tactics had escalated at both levels. In our third case, Equality Now filed its application concerning pregnant schoolgirls and mothers at the height of Tanzania's backlash tactics, after Tanzania's legislative restriction on domestic human rights litigation and its announcement it was withdrawing its special declaration concerning the African Court. Analyzing these three cases thus enables us to process-trace how various state backlash tactics impact NGO litigation at an IHRC, as theorized in our framework.

Abolishing the death penalty

Despite the emerging international norm of abolishing the death penalty (Reference NovakNovak, 2020, pp. 65–113), Tanzania has retained the mandatory death penalty. Tanzanian courts have continued to apply the death penalty, but there has been a moratorium on executions since 1994 (FIDH and LHRC, 2005, p. 7). President Magufuli, in 2017, expressed reluctance to authorize executions and, in 2020, commuted hundreds of sentences (The Advocates, 2021, p. 15). While public opinion has apparently favored retaining the death penalty, it has been challenged numerous times before domestic courts, without effect (FIDH and LHRC, 2005, p. 7; Reference RickardRickard, 2019).

By the mid-2010s, the African Court was “flooded with fair trial cases” against Tanzania (Reference PossiPossi, 2017, p. 311), including many pro se applications from prisoners on death row. With limited legal consciousness, death row prisoners framed their applications as fair trial appeals, though a court-appointed lawyer, William Kivuyo, reframed one application as a right-to-life issue (Rajabu; Reference KivuyoKivuyo, 2021). An official from Reprieve UK picked up on this flood of applications at the Court while doing other work on the death penalty in Sub-Saharan Africa (Reference CampbellCampbell, 2021). Other NGOs were drawn into these dynamics when, for example, the Court requested Sandra Babcock (Faculty Director of the Cornell Center) intervene as amicus curiae and the LHRC provide a legal opinion on the death penalty in Armand Guehi v. Tanzania (2018). Given their shared commitment to advocating against the death penalty, Reprieve UK and the Cornell Center sought to take advantage of the opportunity these applications provided and to facilitate further litigation that would challenge Tanzania's death penalty through the African Court.

In 2017, these international NGOs built a coalition with local Tanzanian partners (NGOs and lawyers) under the Makwanyane Institute, a legal capacity-building forum (Cornell Law School, n.d.; Reference BabcockBabcock, 2021; Reference CampbellCampbell, 2021). Their partners included two African regional NGOs and bar associations based in Tanzania (PALU and EALS); a Tanzanian legal NGO (LHRC); and Tanzanian lawyers, such as Jebra Kambole and William Kivuyo, who had served as legal aid lawyers for pro se applicants at the Court (Reference BabcockBabcock, 2019, pp. 90–1; 2021; Reference CampbellCampbell, 2021; Reference KivuyoKivuyo, 2021). The coalition aimed to obtain a decision condemning Tanzania's mandatory death penalty, promote Tanzania's implementation of capital sentencing reforms in accordance with regional human rights standards, and facilitate new sentencing hearings for death row prisoners in Tanzanian courts (World Justice Project, 2020). The international NGOs planned to indirectly participate in litigation by providing litigation-focused training and capacity-building (e.g., research, help drafting documents) for Tanzanian lawyers, who would directly participate in litigation as legal counsel in death penalty-related cases against Tanzania at the Court (Reference BabcockBabcock, 2019, p. 91; Reference CampbellCampbell, 2021).

Tanzania's domestic-level backlash was a consideration that shaped how international NGOs indirectly, and local partners directly, participated in litigation. The international NGOs normally sought to foreground local partners in their advocacy work, and Tanzania's domestic-level backlash against interventions by international NGOs and foreign funding in the country was an additional justification (Reference BabcockBabcock, 2021; Reference CampbellCampbell, 2021). Both international NGOs and local partners were also conscious of Tanzania's shrinking space for NGOs and human rights defenders, but they assumed local partners that were already engaged in domestic-level advocacy for change in Tanzania would not face additional risk by also participating in international-level advocacy at the Court (Reference CampbellCampbell, 2021; Reference MassaweMassawe, 2021).

Tanzania's international-level backlash in the form of routine noncompliance with African Court decisions eventually became evident to the coalition members, but this did not alter their litigation strategies at the Court. International NGOs assumed Tanzania's backlash was primarily based on the Court's Mtikila decision, which related to the political opposition; their issue did not challenge the Tanzanian government and political system in the same way, and would therefore not attract such resistance (Reference BabcockBabcock, 2021). The coalition thus pursued litigation at the African Court hoping for Tanzania's compliance with decisions.

Beyond the international NGOs' role in coordinating and training local lawyers who could serve as effective legal representation for death row prisoners at the Court, they also facilitated nine existing and new applications by death row prisoners in Tanzania at the African Court (Reference CampbellCampbell, 2021). They interviewed prisoners on death row, provided legal research for cases, coordinated legal representation for applicants with the Court's Registry, and funded some prisoners' legal representation (Reference BabcockBabcock, 2021; Reference CampbellCampbell, 2021; Reference MremaMrema, 2021; World Justice Project, 2020).

Two actions in November 2019—one by the African Court and the other from Tanzania—affected the NGO-led coalition's advocacy opportunities and strategies. In November 2019, the African Court issued a landmark decision that fulfilled one of the NGO-led coalition's key advocacy goals at the Court. In Rajabu (2019), the Court found that Tanzania's mandatory death penalty violates the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights. Though they had not been involved in this case—just the court-appointed lawyer William Kivuyo, who later joined the NGO-led coalition (Reference KivuyoKivuyo, 2021)—the Rajabu decision provided the coalition a foundation for pursuing further goals of advocating for compliance and reform in Tanzania (Reference BabcockBabcock, 2021; Reference CampbellCampbell, 2021; Reference KivuyoKivuyo, 2021). Ongoing and new applications by death row prisoners in Tanzania, however, were still valuable for challenging the death penalty in those individual cases.

In addition, the almost simultaneous onset of Tanzania's escalated backlash against the Court—notably, its announcement of its declaration withdrawal shortly before the Court's Rajabu decision—challenged the NGO-led coalition's litigation strategies at the Court. They were reliant on death row prisoners' direct access to the Court, which the withdrawal revoked. This closing legal opportunity structure mobilized the NGO-led coalition to promote death row prisoners' applications against Tanzania before the withdrawal entered into effect a year later.

But the withdrawal announcement—specifically its apparent trickle-down effects in Tanzania that interacted with domestic-level backlash—also impeded the NGOs' ability and, for one NGO, willingness to facilitate applications to the Court. International NGOs and a Tanzanian NGO, for example, had collaborated on the creation of “infocomics” on the Rajabu decision and the deadline for individuals to file applications at the African Court (Reference CampbellCampbell, 2021; Reference MremaMrema, 2021; World Justice Project, 2020). After the withdrawal announcement, the Tanzanian NGO decided not to be named in this process, given the climate in Tanzania (Reference CampbellCampbell, 2021). The interaction of both domestic- and international-level backlash thus apparently deterred the local NGO's even indirect participation in litigation at the Court. The international NGOs also encountered greater difficulties accessing prisoners, which hindered their ability to facilitate prisoners' applications and distribute the infocomics before the withdrawal deadline (Reference MremaMrema, 2021). NGO officials perceived that, following the withdrawal announcement, prison officers resisted allowing them access to prisoners (Reference MremaMrema, 2021). The prison officers seemed to assume that such access to prisoners, even those with pending cases at the African Court that were unaffected by the withdrawal, was no longer necessary (Reference MremaMrema, 2021). Despite these restrictions, the NGOs facilitated applications by two death row prisoners before the withdrawal took effect (Reference CampbellCampbell, 2021).

Given the impending withdrawal and loss of the NGO-led coalition's legal opportunities for strategic litigation, several coalition members focused their advocacy on ensuring Tanzania's implementation of the Court's existing Rajabu decision on Tanzania's mandatory death penalty. Within Tanzania, Kivuyo (the advocate in Rajabu and subsequent member of the coalition) decided to establish an NGO to more directly advocate for legal reforms with the government (Reference KivuyoKivuyo, 2021). The Cornell Center and Reprieve also planned to convene Tanzanian officials for capacity-building on implementing the Rajabu decision, but this meeting was delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Reference BabcockBabcock, 2021; Reference CampbellCampbell, 2021). Despite this emphasis on nonlitigation forms of advocacy, the NGOs, drawing on their expertise and undeterred by Tanzania's routine noncompliance with Court decisions, also considered adapting their use of the African Court and requesting an advisory opinion (Article 4, African Court Protocol) on the wider applicability of the Rajabu decision to all prisoners in Tanzania (Reference BabcockBabcock, 2021; Reference MassaweMassawe, 2021). Coalition members were thus flexible yet persistent in their advocacy strategies. They were also generally optimistic that the change in the Tanzanian Presidency in 2021 could open new space for advocacy (Reference BabcockBabcock, 2021; Reference CampbellCampbell, 2021; Reference KivuyoKivuyo, 2021; Reference MassaweMassawe, 2021).

This case study of NGO mobilization demonstrates how the onset and escalation of two-level state backlash can prompt NGOs to adapt their advocacy strategies. NGOs initially did not perceive Tanzania's domestic- and international-level backlash tactics were relevant to their organizations or their specific advocacy goals and opportunities. However, when Tanzania's backlash against the African Court escalated to close key legal opportunities at the Court, and this international-level backlash reverberated at the domestic-level, the NGOs altered their strategies. Aligning with our framework's mechanisms through which backlash may promote and deter litigation, international NGOs mobilized to use the African Court before state backlash closed their legal opportunity structure, but the backlash created operational challenges and deterred an NGO from continuing to participate in the coalition's litigation activities while legal opportunities were still available. Tanzania's restriction of the NGO-led coalition's key legal opportunities at the African Court also led its members to shift their advocacy strategies, pursuing other legal opportunities at the Court and focusing on domestic-level advocacy for Tanzania's implementation of an existing Court ruling on the death penalty.

Rights of persons with albinism

PWA face a range of human rights issues including discrimination, special health and educational needs, harmful traditional practices, violence (e.g., killings, ritual attacks), witchcraft-related trade and trafficking of body parts, infanticide, and child abandonment (Reference Burke, Raymond Izarali, Masakure and IbhawohBurke, 2019). In recent decades, given a surge in violence against them, PWA in Tanzania received significant attention and advocacy from media, local and international NGOs, and international organizations (Reference Burke, Raymond Izarali, Masakure and IbhawohBurke, 2019). Under tremendous pressure to protect PWA and their human rights, the Tanzanian government introduced some protective measures (Reference Kajiru and MubangiziKajiru & Mubangizi, 2019, p. 248; UN Independent Expert, 2017, pp. 7–8), but human rights authorities remained concerned (e.g., UN Independent Expert, 2017).

It was a Tanzania PWA who mobilized the CHR—an African regional human rights NGO and academic center at the University of Pretoria—to use the African Court to advocate for the rights of PWA in Tanzania. The individual, a CHR graduate student at the time, brought the issue to the attention of the CHR's Litigation Unit (Reference NyarkoNyarko, 2021), which uses strategic human rights litigation as “an advocacy tool to support other forms of advocacy within the Centre or other partner institutions” (CHR, n.d.). The CHR started preparatory work in 2013 and, by 2016–2017, searched for partner organizations for jointly preparing an application to the Court (Reference NyarkoNyarko, 2021). The IHRDA—another African regional human rights NGO and frequent collaborator with the CHR—was an obvious choice. It had a record of litigating human rights cases across Africa and had more experience than the CHR in litigating at the African Court (Reference NyarkoNyarko, 2021). While the two African NGOs had legal standing to file an application on their own, their advocacy strategy involved having a Tanzanian partner with expertise on the issue that could “take ownership of the outcome” and pressure the Tanzanian government (Reference NyarkoNyarko, 2021).

Tanzania's domestic-level backlash, however, made finding a local partner challenging. A local Tanzanian NGO—a previous collaborator, with significant expertise on Tanzanian PWA—declined to directly participate in litigation as a listed applicant due to concerns about backlash from the Tanzanian government and/or its proxies (PWA-NGO, 2021). The head of the NGO found that the benefits of directly advocating for PWA via the African Court did not outweigh the considerable risks to NGO staff and the vulnerable population they served; therefore, the NGO would only participate indirectly in an advisory capacity (PWA-NGO, 2021). However, another Tanzanian NGO, the LHRC, agreed to directly participate as a listed applicant. By contrast, Tanzania's domestic-level backlash had increased rather than suppressed the LHRC's advocacy, though it exercised caution on occasion (Reference MassaweMassawe, 2021). The LHRC had documented and advocated on the issue of PWA (e.g., LHRC, 2015, pp. 44–7), and regularly engaged in strategic human rights litigation domestically and internationally, including the high-profile Mtikila case against Tanzania at the African Court. It was openly critical of the Tanzanian government's human rights record and domestic-level backlash against human rights accountability (e.g., LHRC, 2018, p. 68). Therefore, unlike the PWA-NGO, the LHRC did not perceive any significant additional risk to directly participating in strategic litigation on PWA at the African Court.

Tanzania's international-level backlash in the form of routine noncompliance, which was evident as the NGOs approached filing the application in 2018, did not deter them. They hoped the application would provide a strong indictment of the Tanzanian legal system's inability or unwillingness to take action on the brutal attacks against PWA (CHR et al., 2018, paras. 34–5). The coalition expected the Court's judgment would be more than symbolic and also result in Tanzania's compliance. Based on the government's steps to protect PWA (though inadequate), Tanzania apparently was not “opposed” to the rights of PWA (Reference FagbemiFagbemi, 2021; Reference NyarkoNyarko, 2021). As with the NGOs from our previous case, these NGOs also assumed Tanzania's backlash in the form of routine noncompliance was directed at other issues (i.e., the Mtikila case, and onslaught of fair trial and death penalty cases), not their own (Reference NyarkoNyarko, 2021). Ultimately, the applicants aimed to get results for victims, either through a decision or, drawing on their expertise on the African Court's rules (Rule 57, Rules of Court), the option of amicable settlement (Reference NyarkoNyarko, 2021).

In late 2019, the applicants were exposed to backlash at both the domestic and international levels. At the domestic-level, in November 2019, Tanzanian police arrested a LHRC human rights lawyer without specifying charges, which the LHRC and other civil society actors condemned as an attempt to silence dissent and indicative of Tanzania's backsliding on human rights (Reference GikandiGikandi, 2019). Consistent with its logic for joining the application, this backlash tactic did not deter the LHRC from continuing to pursue the PWA case at the African Court. Tanzania's escalating international-level backlash against the African Court and announcement it was withdrawing its special declaration “blindsided” the NGOs (Reference NyarkoNyarko, 2021), but did not deter them from pursuing their case. Tanzania's disengagement with the case, even when it proceeded to the merits stage (LHRC, 2019, p. 61), prompted the applicants to draw on their expertise in the Court's rules, adapt their litigation strategy, and request a default judgment under Rule 55 of the Rules of Court (Reference FagbemiFagbemi, 2021; Reference NyarkoNyarko, 2021). Within the period of our data collection, the African Court had not decided on this request, but these NGOs (like the death penalty NGOs) gained some optimism about the case's prospects with the change of Tanzanian leadership (Reference NyarkoNyarko, 2021).

This case echoed findings from the first case. NGOs, again, interpreted international-level backlash in the form of routine noncompliance as not relevant to their advocacy issue, so it did not deter their litigation at the African Court. Tanzanian NGOs again responded differently to the threat of domestic-level backlash: one was deterred from directly participating in litigation, while the other, based on its previous advocacy, saw no additional organizational security risk with directly participating. Finally, the NGOs, given their legal expertise on the African Court, similarly were able to pivot their litigation strategy after Tanzania's escalated backlash against the Court to continue to pursue their advocacy goals.

Rights of pregnant schoolgirls and mothers

In 2017, the Tanzanian government announced that it would enforce a law, which had existed since 2002, allowing pregnant schoolgirls to be expelled or excluded from school and denying them the right to study in public schools (BBC, 2017). By one estimate, over 8000 girls are expelled from school in Tanzania each year, while other pregnant girls stop attending school because they fear expulsion or stigma (Human Rights Watch, 2016). Under Article 11(6) of the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, however, Tanzania is obligated to ensure that children who become pregnant have an opportunity to complete their education. NGOs have advocated for the inclusion of pregnant schoolgirls and young mothers in regular education at public schools (Reference Kassanga and LekuleKassanga & Lekule, 2021), but they had limited domestic political opportunities for this advocacy (Reference MwambipileMwambipile, 2021) and were subject to targeted domestic-level state backlash. In 2017, President Magufuli accused these NGOs of being used by foreign agents (The East African, 2017), and Tanzania's Home Affairs Minister threatened to rescind the registration of organizations advocating on this issue (Reference OdhiamboOdhiambo, 2017).

In 2019, Equality Now—an international NGO with an African regional office in Nairobi, Kenya—decided to submit a case on the issue to the African Court as part of a “multi-pronged [advocacy] approach” (Equality Now, 2020). After years of unsuccessful advocacy on the issue and considering its domestic political opportunities exhausted, this was a measure of “last resort” to have the voices of the victims heard (Reference ChakweChakwe, 2020). Its mobilization around the African Court also followed its previously successful strategy of using litigation at another IHRC, the ECOWAS Court, to challenge a similar law in Sierra Leone (WAVES et al. v. Sierra Leone, 2020).

Equality Now adopted the same strategy as international NGOs from our previous cases and sought a Tanzanian NGO partner for the application, but Tanzania's domestic-level backlash once again was a consideration. One potential Tanzanian partner and repeat player at the African Court, the LHRC, was unavailable to participate in the application for unrelated reasons (Reference MassaweMassawe, 2021), but Tanzania's domestic-level backlash apparently influenced how another potential Tanzanian partner participated in the application. Equality Now had previously advocated on this issue with the Tanzania Women's Lawyers Association (TAWLA) and was interested in it being a co-applicant (Reference MurungaMurunga, 2021). TAWLA's CEO Tike Mwambipile weighed the costs and benefits of TAWLA being a party to the application. Reference MwambipileMwambipile (2021) similarly felt TAWLA had exhausted its domestic advocacy opportunities but also was aware of the political climate in Tanzania. Ultimately, after guidance from a local lawyer with expertise in the African Court, they decided that Mwambipile should be an individual applicant under the assumption that having an individual, not merely NGOs, as an applicant would be more effective for litigation (Reference MwambipileMwambipile, 2021). TAWLA could instead indirectly participate as amicus curiae (Reference MwambipileMwambipile, 2021).

Consistent with our other case studies, Tanzania's backlash against the African Court through persistent noncompliance did not deter the coalition's mobilization at the Court. They assumed Tanzania's noncompliance was not systematic and was directed at other issues, so Tanzania could comply with an African Court decision on the pregnant schoolgirls ban (Reference MurungaMurunga, 2021; Reference MwambipileMwambipile, 2021). Their litigation strategy aimed for compliance, but even without compliance, international litigation would draw attention to the issue, and render a Court decision that could further their advocacy for change in Tanzania and other African countries (Reference MurungaMurunga, 2021; Reference MwambipileMwambipile, 2021).

However, unlike the other case studies, the coalition was still preparing its application to the Court when Tanzania's international-level backlash escalated with its declaration withdrawal announcement. One Equality Now official speculated that the Tanzanian government may have become aware of their planned application and that may have catalyzed the withdrawal announcement (Reference MurungaMurunga, 2021), but this was not a deterrent, given their advocacy goals. Tanzania's international-level backlash increased the coalition's mobilization to submit the application on November 18, 2020 (Reference ChakweChakwe, 2020), just days before the withdrawal took effect and they would lose direct access to the Court. This mobilization reflected their relatively high level of expertise on the African Court and understanding of the legal implications of the withdrawal, contrary to the widespread confusion about the withdrawal among many within the international and Tanzanian human rights community (ACC, 2021).

The application contributed to the coalition's advocacy goals, despite Tanzania's escalated backlash against the Court. Tanzania was generally inactive in the case, except for an application for an extension to submit its filings (Reference MurungaMurunga, 2021). But the application mobilized numerous civil society actors, including TAWLA and the Commission for Human Rights and Good Governance of Tanzania (CHRAGG), to be amicus curiae (Reference MurungaMurunga, 2021; Reference MwambipileMwambipile, 2021). The applicants found such developments at the Court served their advocacy interests, as the Court sent updates to the parties to the case (including Tanzania) and thus maintained pressure on Tanzania (Reference MwambipileMwambipile, 2021). The coalition also found their ongoing application valuable for when Tanzania's leadership (and some state policies) changed in 2021; they, like NGOs from our other case studies, saw new opportunities for their case at the African Court and their domestic-level advocacy with the new Tanzanian leadership (Reference MurungaMurunga, 2021; Reference MwambipileMwambipile, 2021).

This case further demonstrates how international NGOs seek local partners for their international litigation, but domestic-level state backlash can have a chilling effect on whether and how local NGOs participate. It also provides further support for NGOs' perceptions of international backlash in the form of routine noncompliance mediating this backlash tactic's impact. Again, the coalition assumed this state backlash was isolated and their issue-specific international litigation could achieve state compliance. Tanzania signaling its limitation of the African Court's accessibility, as expected, promoted the coalition initiating international litigation while this legal opportunity was still available. They continued their litigation strategy, even when they speculated it could be prompting the escalated state backlash. The coalition leveraged the litigation process, despite the state's disengagement, to mobilize more actors on the issue and to support its other advocacy strategies.

DISCUSSION

Our three cases process-traced how Tanzania's two-level backlash tactics, intervening at different points in NGOs' mobilization and litigation processes, shaped whether and how NGOs participated in litigation at the African Court. Our diverse case selection (Reference GerringGerring, 2007, pp. 97–9) captured various mechanisms of the framework. Aligning with our theoretical expectations, state backlash at the domestic and international levels both promoted and deterred NGOs choosing international litigation as a human rights advocacy strategy. Deterrence arose in virtually all three cases when international NGOs sought domestic NGO partners for international litigation. Domestic-level backlash deterred some domestic NGOs' (direct) participation in litigation when they perceived litigation could increase their risk of state reprisals. But when domestic-level backlash limited domestic political and legal opportunities, it promoted both international and domestic NGOs shifting their advocacy from the domestic level to the African Court. International-level backlash only significantly influenced NGO mobilization when it was extreme and restricted NGOs' ability to litigate at the African Court. With the milder state tactic of routine noncompliance, NGOs still rationalized the possibility for state compliance with a Court decision, alongside their other litigation-related strategies that did not depend on compliance. State backlash through restricting the Court's authority promoted not only litigation before the legal opportunity structure closed, but also adaptation of NGOs' strategies for leveraging international litigation and combining it with other advocacy strategies.

Supporting the legal mobilization approach, our analysis showed how changing legal opportunity structures alone could not explain NGOs' mobilization and strategies at IHRCs. NGOs used legal opportunity structures beyond the functions they were designed to perform (e.g., publicizing an application to mobilize other actors around their issue). Furthermore, factors such as legal consciousness, legal expertise, and networks clearly affected how NGOs interpreted and responded to state backlash tactics, including when it restricted their legal opportunity structures. For example, echoing scholarship based on the ECtHR (Reference CichowskiCichowski, 2016), NGOs' variable legal expertise in the African Court's rules and procedures significantly affected how they adapted their strategies at the Court in the context of Tanzania's declaration withdrawal, with some exploiting remaining legal opportunities at the Court (i.e., advisory opinions or default judgments) better than others. Legal consciousness also apparently influenced how international-level backlash trickled down to the domestic level, with societal actors' misunderstandings posing operational challenges for NGOs. The prominence of such factors can vary (Reference VanhalaVanhala, 2018, p. 406) and should be contextualized for each state and IHRC. For example, we might expect NGOs tend to have greater legal consciousness and expertise in older IHRCs' rules and procedures, compared with newer IHRCs like the African Court. Finally, NGOs' networks influenced who mobilized. Notably, our cases flipped the conventional “boomerang” model of transnational advocacy (Reference Keck and SikkinkKeck & Sikkink, 1998): international NGOs sought out domestic partners to facilitate their advocacy for change in that state and potentially other states (see Reference Pallas and BloodgoodPallas & Bloodgood, 2022).

Our cases of NGO mobilization against Tanzania at the African Court, overall, demonstrate the remarkable persistence of NGOs' international human rights litigation strategies despite escalating state backlash at both the domestic and international levels. Relatedly, our analysis suggests the potential for NGOs' mobilization at an IHRC to contribute feedback effects and escalate state backlash against the IHRC. NGOs may not be aware of their potential contributions to state backlash. The death penalty NGOs were not concerned about their litigation contributing to backlash, while the NGOs advocating for PWA assumed those were key cases provoking the backlash. A NGO's perception that its litigation provoked backlash against the Court did not deter it from pursuing this litigation. Generally, NGOs' strategic behavior focused on advocating for their issue, rather than defending their legal opportunities and the IHRC from backlash. This is an important caveat for accounts that stress NGOs' contributions to institution-building in IHRCs (e.g., Reference HaddadHaddad, 2018), to IHRCs' resilience against state backlash (Reference Gonzalez-Ocantos and SandholtzGonzalez-Ocantos & Sandholtz, 2022, pp. 100–1), and to expanding legal opportunity structures more generally (e.g., Reference VanhalaVanhala, 2017, p. 125).

CONCLUSION