The problem of regulatory instrument choice has typically been framed as a choice between technology-based or performance-based regulation (Reference BreyerBreyer 1982; Reference ViscusiViscusi 1983). Regulators can craft rules that either mandate specific technologies or behaviors (technology-based regulation) or require that certain outcomes will be achieved or avoided (performance-based regulation). Even market-based regulatory instruments, around which an important literature has emerged (Reference Ackerman and StewartAckerman & Stewart 1985; Reference Hahn and HesterHahn & Hester 1989; Reference Mäler and VincentStavins 2002), are still linked either to technologies or, more frequently, to the outcomes of firm behavior. Market-based instruments do provide distinctive incentives to firms, but nevertheless regulators enforcing market-based regulation still measure firms’ performance for the purpose of either assessing taxes or determining if firms possess an adequate number of tradeable permits.

The treatment of both conventional and market-based instruments in the academic literature has revealed important lessons about the effectiveness of different regulatory standards in advancing social goals. Yet missing from the traditional emphasis on technology-based and performance-based regulation has been much systematic attention to a third type of regulatory instrument that we call “management-based regulation.”Footnote 1 Management-based regulation does not specify the technologies to be used to achieve socially desirable behavior, nor does it require specific outputs in terms of social goals. Rather, a management-based approach requires firms to engage in their own planning and internal rule-making efforts that are supposed to aim toward the achievement of specific public goals (Reference Bardach and KaganBardach & Kagan 1982:224).

Although attention to management-based approaches has been sparse relative to the literature on other kinds of regulatory instruments, management-based strategies have been used in a variety of regulatory contexts around the world, including in Australian occupational safety and health regulation (Reference GunninghamGunningham 1996), U.S. mine safety regulation (Reference Ayres and BraithwaiteAyres & Braithwaite 1992), and British railway regulation (Reference HutterHutter 2001). The use of management-based regulation in these and other regulatory settings, including on issues such as food safety and environmental protection, appear to have arisen independently of each other, with comparatively little analysis of management-based regulation as a general regulatory strategy. While several scholars have noted a few applications of these strategies, as well as some of their advantages and disadvantages (Reference Ayres and BraithwaiteAyres & Braithwaite 1992; Reference Gunningham and JohnstoneGunningham & Johnstone 1999; Reference Coglianese, Nash, Coglianese and NashCoglianese & Nash 2001), little attention has been paid to the conditions under which management-based regulation is an effective, if not preferred, regulatory strategy.

In this article, we offer an analysis of the effectiveness of management-based regulation relative to other regulatory strategies.Footnote 2 We begin, in Part I, by distinguishing management-based regulation from alternative regulatory instruments and outlining its characteristic features by reference to three case studies: food safety, chemical accident regulation, and pollution prevention. Not only do these case studies contribute to the literature by showing new areas where management-based strategies have been deployed, but they also serve to ground the theoretical analysis that we develop in Parts II and III. In Part II, we present an analytical framework showing the conditions under which management-based regulation can be expected to be relatively more effective than technology-based and performance-based regulation. In Part III, we take this analysis a step further by using decision-tree analysis to reveal the specific choices regulators confront in designing a management-based strategy in those cases where one is appropriate. In Part IV, we return to our three case studies to show how our theoretical analysis fits with the available evidence on the implementation and effectiveness of management-based regulation in these cases.

I. What Is Management-Based Regulation?

Regulation may intervene at one of three stages of any organization's activities: the planning, acting, or output stages. Outputs include both private and social goods, that is, saleable products or services (private goods) as well as the positive and negative externalities (social goods and bads) that affect society. The social outputs of an organization's production include the traditional notion of public goods (e.g., a clean environment) as well other cases of “market failure” (e.g., worker safety). The challenge for regulation arises because private actors tend to underproduce social goods (or overproduce social bads), thus creating a need for the regulator to intervene (Reference Viscusi, Vernon and HarringtonViscusi, Vernon, & Harrington 2000).

The ultimate goal of all regulation is therefore to change the production of social outputs, but regulatory intervention targeted at any of the three stages will potentially affect outputs. We therefore distinguish between different types of regulatory instruments based on the organizational stage that they target (Figure 1). Technology-based approaches intervene in the acting stage, specifying technologies to be used or steps to be followed. Performance-based approaches intervene at the output stage, specifying social outputs that must (or must not) be attained.Footnote 3 By contrast, management-based approaches intervene at the planning stage, compelling regulated organizations to improve their internal management so as to increase the achievement of public goals.

Figure 1. Stages of Organizational Production and Types of Regulation

Under management-based regulatory strategies, firms are expected to produce plans that comply with general criteria designed to promote the targeted social goal. Regulatory criteria for management planning specify elements that each plan should have, such as the identification of hazards, risk mitigation actions, procedures for monitoring and correcting problems, employee training policies, and measures for evaluating and refining the firm's management with respect to the stated social objective. These plans sometimes are made subject to approval or ratification by government regulators, but as we discuss in Part III, they need not be under all types of management-based regulation. Similarly, under some management-based regulations (but not others), firms are required to produce documentation of subsequent compliance or are subjected to reviews by regulators or third-party auditors to certify compliance.

Although management-based regulation will typically require information collection (such as hazards analysis), we should be clear about how management-based rules differ from rules that require information disclosure. So-called informational regulation has garnered much attention in recent years (Reference Kleindorfer and OrtsKleindorfer & Orts 1998; Reference SunsteinSunstein 1999; Reference KarkkainenKarkkainen 2001; Reference GrahamGraham 2002). Regulations that require firms to collect and disclose information include product labeling laws and regulations that mandate the disclosure of various outputs of social concern, from accident rates to emissions of toxic chemicals. Deciding how to classify these kinds of regulations—whether as technology-, performance-, or management-based—will depend on their intended purpose. When their purpose is to provide information to the public to correct for information asymmetries or to promote more informed consent or deliberation, then information disclosure should be viewed as a regulatory goal, not a distinct regulatory strategy. The goal in such cases is to provide greater availability of information to the public, and the challenge for the regulator is to choose among the available regulatory instruments to mandate either the means of information disclosure (e.g., by specifying precise labeling requirements) or the ends (e.g., by requiring the attainment of the goal of information disclosure).

However, informational regulation can have more than one purpose. If the purpose of information disclosure is to change the behavior of the firm by making managers more aware of and concerned about their organization's social outputs, then we would consider information disclosure rules to be elementary forms of management-based regulation. The gathering of information is, after all, a necessary step in any management or planning process. That said, management-based regulation typically involves much more than a requirement to generate and disclose information. The type of management-based regulation we analyze here goes much further by requiring firms to develop plans and procedures based on the information they gather and the analysis they conduct.

Management-based approaches hold a number of potential advantages over traditional regulation. They place responsibility for decisionmaking with those who possess the most information about risks and potential control methods. Thus, the actions that firms take under a management-based approach may prove to be less costly and more effective than under government-imposed regulatory standards (Reference Ayres and BraithwaiteAyres & Braithwaite 1992). By allowing firms to make their own decisions, managers and employers are more likely to view their own organization's rules as reasonable, and as a result there may be greater compliance than with government-imposed rules (Reference Ayres and BraithwaiteAyres & Braithwaite 1992; Reference Kleindorfer, Sexton, Marcus, William and BurkhardtKleindorfer 1999; Reference Coglianese, Nash, Coglianese and NashCoglianese & Nash 2001).Footnote 4 In this way, as well as by enlisting the assistance of private, third-party certifiers, management-based regulatory strategies may help mitigate the problems associated with limited governmental enforcement resources. Finally, by giving firms flexibility to create their own regulatory approaches, management-based approaches enable firms to experiment and seek out better, more innovative solutions.

Management-based regulation has been implemented in a variety of areas, including recently in the areas of food safety, chemical accident avoidance, and pollution prevention. The characteristic features of management-based regulation can be better understood by reference to the regulations that govern these three areas. We return later to these three cases to show how they illustrate our theoretical analysis and to review the available empirical evidence on the effectiveness of management-based regulatory strategies in these areas.

Food Safety

Food safety is an important regulatory responsibility. In the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that about 5,000 deaths each year and 76 million illnesses are linked to unsafe food (Reference Mead, Slutsker, Dietz, McCaig, Bresee, Shapiro, Griffin and TauxeMead et al. 1999). The federal government's involvement in the regulation of food safety dates to the early part of the twentieth century, when Congress adopted statutes requiring the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to provide continuous inspection of meat processing plants (Federal Meat Inspection Act of 1907 §§ 601-95; Poultry Products Inspection Act, 2000, § 451) and delegating regulatory authority over most other food products (including fish) to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Federal Food and Drugs Act of 1906 §§ 301-97). By law, USDA inspectors are required to conduct continuous, on-site inspections of meat processing plants to verify sanitary plant conditions and to conduct visual and olfactory tests of carcasses (American Federation of Government Employees v. Veneman 2002), a process commonly referred to as “poke and sniff” inspections.

More recently, new food safety challenges have emerged as faster, more innovative production processes in the food industry have placed new demands on inspectors’ time (USDA 1995). In addition, heightened public expectations and the new processing methods have contributed to increasing concerns about microbial food contamination, which is difficult to detect by the traditional “poke and sniff” methods. In response to these challenges, regulatory authorities around the world have developed an alternative regulatory strategy, Hazards Analysis and Critical Control Points (HACCP). HACCP requires firms to evaluate, monitor, and control potential dangers in the food handling process. In 1996, the USDA issued new regulations requiring meat and poultry processing firms to undertake several management steps to reduce the incidence of food contamination (USDA 1996). In addition, the FDA has imposed similar HACCP requirements on other food producers (FDA 1995, 2001a), and HACCP has become a globally accepted regulatory strategy for addressing food safety (Reference LazerLazer 2001).

HACCP first requires firms to identify the potential hazards associated with all stages of food processing and to assess the risks of these hazards occurring. Food processors are expected to use a flow chart to aid them in analyzing the risks at every stage of production after the food enters the plant in question. HACCP next requires firms to identify the best methods for addressing food safety hazards. The firm must identify all “critical control points” (CCPs), or points in the production process at which hazards can likely be eliminated, minimized, or reduced to an acceptable level. For each CCP, the firm must establish a minimum value at which the point must be controlled in order to eliminate or minimize the hazard. Having developed a methodology for dealing with hazards, the firm is required to ensure that it complies with that methodology. The firm must list the procedures that will be used to verify that each CCP does not exceed its critical limit, and it must determine and indicate how frequently each procedure will be performed.

Each firm's HACCP plan should also indicate the actions the firm proposes to use to correct its operating procedures if a CCP is discovered to have exceeded its limit. As part of its corrective action, the firm must ensure that the cause of the deviation is identified and eliminated, that the CCP is “under control” after the corrective action is taken, that steps are taken to prevent recurrence, and that products adulterated by the deviation are not placed on the market. The firm is expected to develop a methodology for monitoring and evaluating the effectiveness of its HACCP plan. Furthermore, in order to permit effective self-evaluation and government oversight, HACCP imposes extensive record-keeping requirements on firms.

The Food Safety Inspection Service (FSIS) of the USDA verifies the firm's compliance with the agency's HACCP requirements. The FSIS has the right to review the HACCP plan and all records pertaining to it. In addition, it may also collect samples and make its own direct observations and measurements. Firms need not get the FSIS's pre-approval for their HACCP plans, although they can later be found to be in violation of the HACCP regulation if their plans fail to meet the government's requirements or if they ship contaminated or spoiled food.

Regulators have produced nonbinding guides that describe how to develop HACCP plans, but the regulations themselves provide firms with substantial latitude in managing their food safety risks—providing examples of possible hazards and responses, but not requiring any particular action. The rules direct firms to choose for themselves what limits to set on the CCP and what internal procedures and technologies they deploy.

Industrial Safety

As with food safety, government plays a role in promoting the safe handling of toxic, reactive, and flammable chemicals. Following a catastrophe in 1984 in Bhopal, India, where more than 2,000 people died as the result of an accident at a Union Carbide chemical facility, regulators in the United States began to pursue new strategies for reducing the risk of chemical accidents. In 1990, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) announced that it was considering a new federal regulation governing the management of chemical processes (OSHA 1990). OSHA's proposed approach would establish standards for “process safety management” (PSM) of highly hazardous substances. That same year, Congress adopted new amendments to the Clean Air Act that required the U.S. Department of Labor (through OSHA) to finalize a set of regulations designed to protect workers from chemical accidents. The Act specified that OSHA develop a list of toxic, flammable, reactive, and explosive chemicals and then that it develop a series of management practices that firms must implement if they use more than a specified level of such chemicals (Clean Air Act Amendments 1990 § 304).

The regulation OSHA adopted in 1992 imposed management standards on firms across the entire economy, from manufacturing firms to chemical and pharmaceutical firms, and from the petroleum industry to public wastewater treatment facilities (OSHA 1992). Much as with HACCP, the PSM regulation requires firms to implement a multistep management practice to assess risks for chemical accidents, develop procedures designed to reduce those risks, and take actions to ensure that procedures are carried out in practice.

The core of OSHA's PSM protocol is a process hazard analysis. Firms must undergo an extensive analysis of what could potentially go wrong in their facilities’ processes and what steps must be in place to prevent such accidents from occurring. OSHA defines “process” broadly to mean any use, storage, handling, or manufacture of such chemicals at a site. Each such process must be analyzed separately, and then firms must rank each according to factors such as how many workers could potentially be affected and the operating history of the process, including any previous incidents involving the process. Firms must next identify both actual and potential interventions to reduce hazards associated with each process, including control technologies, monitoring devices, early warning systems, training, or safety equipment.

Based on this analysis, firms must develop written operating procedures for both normal operating conditions and emergency situations. These procedures must be made available to employees who work with the chemical processes. In addition, OSHA requires that firms continuously review these procedures and update them as necessary to reflect process changes, new technologies, or new knowledge. Firms are required to certify their operating procedures on an annual basis and to provide for compliance audits every three years. By tracking process and incident data in a systematic way through process safety management, firms are well-positioned to make modifications that can improve worker safety.

OSHA's standard is designed primarily to protect workers from the hazards of chemical accidents. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has adopted a similar management-based regulation designed to protect the broader public from the accidental release of hazardous chemicals (U.S. EPA 1996; see also Reference Chinander, Kleindorfer and KunreutherChinander, Kleindorfer, & Kunreuther 1998). Like OSHA, EPA requires firms that use specified toxic or flammable chemicals to conduct a hazard analysis, establish a management plan to prevent accidental releases, and create a plan for responding to emergencies (Reference JordanJordan 1997). Indeed, there is a considerable overlap between OSHA's PSM requirements and EPA's risk management plans (RMPs). As a result, both agencies have coordinated their programs so that firms covered by both regulations are able to implement a single management system that satisfies both agencies’ requirements.

The EPA and state environmental agencies are authorized to make unannounced inspections of facilities to determine whether firms have developed risk management plans consistent with EPA's regulation and whether firms have followed their own plans. EPA has also recently experimented with the use of private, third-party auditors, including insurers’ loss prevention engineers, to ensure compliance with its management-based requirements (Reference Kunreuther, McNulty and KangKunreuther, McNulty, & Kang 2002).

Pollution Prevention

Conventional regulatory efforts have aimed to reduce overall levels of pollution produced by firms. In the United States, these efforts have taken the form of a series of major environmental statutes and thousands of additional pages of federal and state regulations. Much of the existing system of environmental regulation depends on technology-based and performance-based standards (Office of Technology Assessment 1995). Although these conventional regulations have significantly reduced the levels of certain pollutants (U.S. EPA 2000), other environmental concerns continue to persist. Moreover, by relying heavily on technology-based standards, existing regulation may discourage innovation and the diffusion of alternative means of improving environmental quality. In particular, firms that are required to invest in particular control technologies may come to rely on these technologies to reduce pollution, to the exclusion of implementing other manufacturing or process changes that would actually reduce the amount of polluting chemicals used in production.

The EPA and a number of state environmental agencies have adopted a variety of voluntary efforts to encourage firms to engage in pollution prevention, or specifically, to reduce their overall use of toxic chemicals (Reference StewartStewart 2001). A few states have gone still further to impose requirements on firms to manage their operations to achieve reductions in the use of toxic substances. The Massachusetts Toxic Use Reduction Act (TURA) represents one such effort at management-based regulation (Toxic Use Reduction Act 1994). TURA requires firms that use large quantities of toxic chemicals to analyze the use and flow of chemicals throughout the facilities, develop plans to reduce toxics use, and submit planning reports to state environmental agencies (Reference KarkkainenKarkkainen 2001). The state also requires that a state-authorized pollution prevention planner certify each plan. Although firms are required to go through the planning process and develop a system for reducing the use and emissions of toxic substances, TURA does not require firms to comply with their own plans. Moreover, firms’ plans are considered proprietary and are therefore not made available to the public, thus putting to the side possible community pressures that publicly available plans might generate. Nevertheless, the program aims to encourage firms to make gains in terms of pollution prevention by requiring them to go through a planning process.

II. The Role for Management-Based Regulation

Having defined and illustrated what we mean by management-based regulation, we turn next to the circumstances under which a management-based regulatory strategy will likely prove effective, especially relative to technology-based and performance-based options. Our theoretical analysis begins with the assumption that government should choose the regulatory option that minimizes the costs of achieving a set of regulatory objectives (such as environmental, safety, or distributive goals). The choice between adopting a technology-based, performance-based, or management-based regulation will therefore depend on the relative overall net social gain each alternative would provide, given a specified regulatory objective.

Technology-based regulation requires firms to adopt specific technologies or methods designed to promote social goals such as environmental quality, worker safety, or consumer protection. Although technology-based regulation has been effective in correcting certain market failures, it can prove to be either over- or underinclusive, meaning that it can sometimes require too much investment in areas where the costs of regulation exceed the benefits, or too little in areas where the benefits of regulation would outweigh the costs (Reference HahnHahn 1996). In addition, regulation that imposes requirements for specific technologies can eliminate incentives for firms to seek out new technologies that would achieve public goals at a lower cost (Reference Gunningham and JohnstoneGunningham & Johnstone 1999). Thus, even if a required technology seems effective at the time a regulation is adopted, it may prove significantly less cost-effective than the technologies that would have been selected if firms had flexibility and the opportunity to innovate.

In contrast, a performance standard specifies the level of performance required of a firm but does not specify how the firm is to achieve that level. For example, a regulation may limit the exposure of workers to particular hazardous chemicals but not specify how those exposure levels are to be achieved. Such an approach provides firms with the flexibility to find less costly ways to achieve these performance levels (Reference GunninghamGunningham 1996). However, when performance standards apply uniformly to all firms, they too can be over- and underinclusive since they require heterogeneous firms, each with different compliance costs, to control to the same level (Reference HahnHahn 1989). Market-based performance regulations are nonuniform, and thus firms with lower marginal compliance costs have incentives to achieve higher than average performance levels, making up for lower performance by firms facing higher costs. Market-based performance standards can thus reduce overall costs and provide still greater incentives for firms to innovate (Reference Hahn and HesterHahn & Hester 1989; Reference StavinsStavins 1989; Reference TietenbergTietenberg 1990; Reference Pildes and SunsteinPildes & Sunstein 1995).

Whether market-based or uniform, all performance standards require that government effectively monitor and assess the regulated outputs. When this requirement is met, performance-based regulations will generally prove more cost-effective than technology-based standards, for the former allow firms the option of selecting the lowest-cost control or prevention options or innovating to find such lower-cost options. Yet it is often difficult or prohibitively expensive to assess critical outputs (Reference Ayres and BraithwaiteAyres & Braithwaite 1992), and when this is the case the advantages of performance-based standards will be weaker.

Management-based regulation shares some of the advantages of performance-based regulation in that it allows firms the flexibility to choose their own control or prevention strategies. But it is distinguished from performance-based regulation in that management-based regulation mandates specific, and sometimes extensive, planning and management activities. Since management quality is often an important component to achieving regulatory goals (Reference Kagan, Gunningham and ThorntonKagan, Gunningham, & Thornton 2002), management-based regulation requires firms to engage in internal actions that the regulator hopes will lead to improved private management of issues with social ramifications. Clear planning, monitoring, and procedures within a firm can be an important factor in preventing or reducing the social harms that motivate regulation in the first place, especially with respect to problems that arise from breakdowns in complex systems or that require coordination among a large number of interactive human and technological processes.

Of course, firms already have incentives to manage their operations well, and sometimes management motivated by firms’ private interests will overlap somewhat with the larger social interest. For example, food processors have their own private interests in maintaining food safety, for a company that distributes food products known to make people ill will not stay in business very long. Similarly, in some cases improved environmental management may reduce the waste of materials and thereby lower a firm's costs at the same time that it improves the environmental quality in the surrounding community. However, any analysis of the choice of regulatory instruments begins with the assumption that the overlap between private incentives and social goals is incomplete. A decision to choose between technology-based, performance-based, or management-based regulation presumes that there is a need for government regulation in the first place.Footnote 5

In many cases there will be such a need, even if firms have some nonregulatory incentives to manage their operations in such a way as to increase social benefits. Private managers may not always exploit the full potential overlap between their private interests and social interests because the expected private gains from finding these “win-win” scenarios does not justify the costs of searching for them (Reference Palmer, Oates and PortneyPalmer, Oates, & Portney 1995).Footnote 6 The type of analysis that is required under a management-based regulatory approach may overcome this limitation by forcing firms to confront and assess risks that they might otherwise find insufficiently beneficial to study. Once firms find themselves compelled to invest in search costs because of a management-based regulation, they may well then find additional ways of operating their enterprise that yield both private and social gains. Of course, not all the options that firms identify will be ones where the private net benefits are positive, even if the social net benefits are. The regulator may therefore need to require firms to respond to problems and implement responses identified through the planning that firms are compelled to conduct.Footnote 7

We have presented the regulators’ choice as one among three basic types of instruments that roughly correspond to three stages of an organization's process: technology-based, performance-based, and management-based regulation. When should a regulator use one type of instrument over another? In a world where government faced no transaction costs in identifying and enforcing an effective response, any regulatory instrument would be optimal (Reference CoaseCoase 1960).Footnote 8 By transaction costs, we mean the costs involved in selecting and implementing an effective rule, such as the costs of research, analysis, monitoring, and enforcement. For example, in the absence of these transaction costs, the government could craft an infinitely detailed technology-based regulation, where each technological requirement was delicately balanced as to the benefits and burdens imposed on society and where regulatory change was appropriately elastic in the face of new technological developments. If government used a performance-based rule, it could precisely determine the social costs of particular outputs and impose the appropriate tax (or industry-wide quota for a trading system), and in the absence of transaction costs businesses would effortlessly adjust internal processes to internalize these costs. Finally, if management-based tools were used, government would easily evaluate the planning and subsequent implementation of controls on the production of social externalities by private actors.

Yet we live in a world with transaction costs (Reference KomesarKomesar 1994; Reference WilliamsonWilliamson 1981), and government must invest its limited resources in deciding to encourage some behaviors and deter others. The question therefore becomes one of selecting the regulatory instrument that, under given conditions, achieves the greatest net social gain or that minimizes both the regulated entities’ compliance costs and the government's costs of selecting and implementing a standard that achieves a given regulatory objective. For some problems, it will be clearly worthwhile for government to invest large resources to find an optimal technological solution or to devise an appropriate and effective measure of performance. Yet for other problems, the technological solutions or the performance measures might be too costly for government to devise, and they might be more effectively identified by the firms themselves. Indeed, in many situations, the costs will be lower for market actors relative to government to understand the linkages between their behavior and particular outputs.

We will assume, for sake of analysis, that it is generally easier for a market actor to determine how it can achieve the ideal output of social goods than for the government. This assumption, by itself, does not determine the choice of instrument, since market actors do not have the motivation to incur the costs needed to achieve social goods nor to reveal their superior knowledge of the relationship between their behavior and its effects (Reference Ayres and BraithwaiteAyres & Braithwaite 1992; Reference Parson, Zeckhauser, Coglianese, Heckelman and CoatesParson, Zeckhauser, & Coglianese 2003). The key question is whether government can take advantage of the lower relative costs that private actors face so that the net social benefits will be higher than under alternative regulatory approaches. This question turns on how costly it is for government relative to the firm to select appropriate targets for outputs, identify the linkages between actions and outputs, and determine a suitable set of technologies or behaviors to reduce the undesirable outputs (or increase desirable ones).

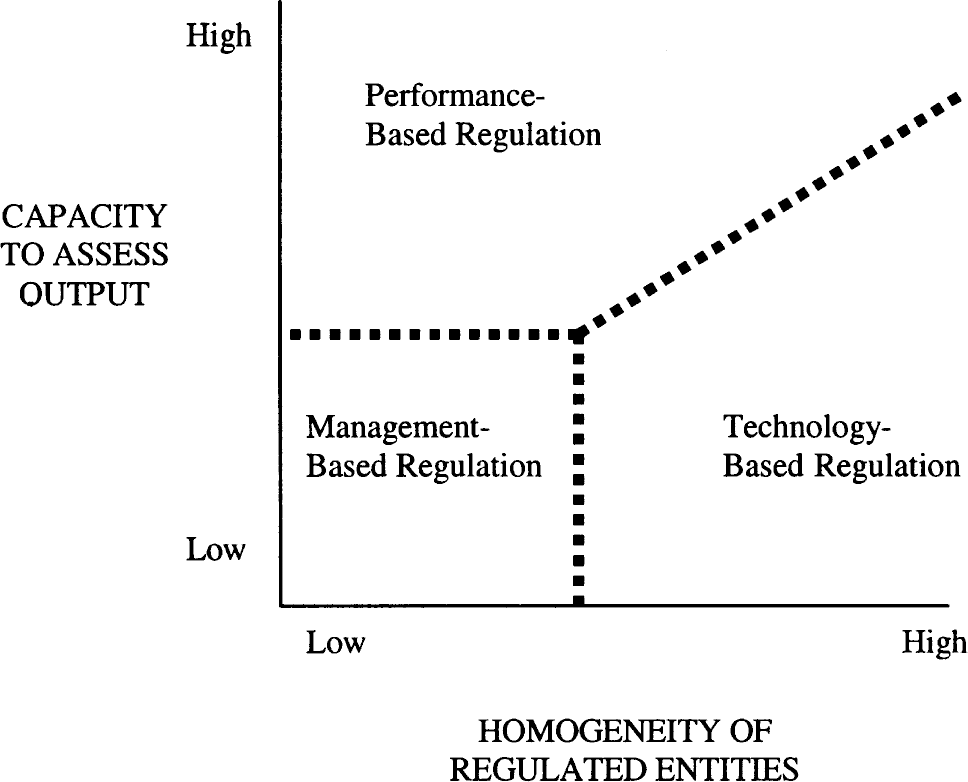

The relative costs to government can be modeled along two salient dimensions (Figure 2). The first dimension represents the government's costs of assessing the social outputs of a private party. By “assessing social output,” we mean that the government can measure outputs accurately. For example, in the environmental area, this would mean that the government can monitor emissions from the various facilities that are covered by an emissions regulation.Footnote 9 When the costs of measuring social outputs or well-correlated proxies for social outputs are low, performance-based regulation will be a viable instrument choice for government.

Figure 2. Necessary Conditions for Effective Use of Performance, Technology, and Management Standards

The second dimension represents the degree of homogeneity of the regulated entities, both across locations and over time. A regulated sector will be homogeneous if (1) at a given point in time, most private actors have similar operations, and (2) the technology used by these actors tends to be stable over time. In situations where the regulated entities are homogeneous in these ways, technology-based regulation will be a viable government strategy, as it will be less costly to identify cost-effective strategies for achieving the regulatory goal. However, the more heterogeneous a sector, either across firms or over time, the more acute will become the disadvantages of technology-based standards.

Perhaps the most challenging scenario for the government regulator arises when it is capable of neither measuring output nor developing an appropriate technology standard due to industry heterogeneity. The difficulty with assessing outputs makes performance-based regulation impractical, and the high degree of heterogeneity makes technology standards undesirable. However, this is a scenario where a strong theoretical justification exists for management-based regulation, all other things being equal.Footnote 10 Assuming the government has a general understanding of the social objectives (even though it cannot measure or monitor them well), it may be possible to establish criteria for planning and general parameters for effective management, and then to enforce management practices that are consistent with these planning requirements and with firms’ own plans. That is, as one moves from the lower right-hand quadrant to the lower left-hand quadrant of Figure 2, the larger becomes the informational advantage of firms and the greater the potential social benefit to granting firms flexibility in how they achieve the regulator's goals. These benefits, of course, are just potential, because the question remains whether the regulator can design management-based regulation in a way that ensures that firms adequately internalize social goals in their planning processes and then adequately implement those plans. If it cannot, then firms will likely not implement costly plans in ways that advance public goals.

III. Designing Management-Based Regulation

Using management-based regulation effectively requires more than the identification of the conditions under which it may be an appropriate choice. As is evident from the three cases we introduced in Part I, regulators face choices in how they design management-based regulations. Some management-based regulations require firms to engage in planning only, while others require them to engage in planning and to follow through by implementing the plans they are mandated to create. Regulators also face choices about how prescriptive to be in directing firms’ management practices, about whether to require firms to submit plans for government review and approval before implementation, and about how to monitor firms’ compliance. In this part, we extend our analysis of management-based regulation by examining some of the main choices about its design. The most significant of these choices is whether to mandate (1) planning only, (2) implementation of any planning a firm undertakes, or (3) both. We begin by developing a model for analyzing the regulator's choice of mandating planning, implementation, or both.Footnote 11

A. Mandating Planning, Implementation, or Both

As we noted in Part I, management-based regulation is distinctive in that it aims to direct action at the planning stage of the production process. Government seeks to direct such action by backing up a management-based regulation with sanctions. The question for the government decision maker becomes whether, given finite enforcement resources, it should mandate planning by itself, implementation of planning by itself, or both planning and implementation. To address this question, we develop a two-stage model of sanctioning using parameters that capture the regulator's capacity to alter a firm's incentives so as to incorporate public goals into its planning and subsequent implementation process.

We begin by assuming that from the firm's perspective, management-based regulation has two stages: planning and implementation (Figure 3). Government possesses some capacity to monitor whether a firm plans according to stated criteria, as well as some capacity to monitor whether the firm has implemented its plan. We further assume the following: the expected value of the penalty for not planning (and not implementing) is P 1 (>0); the expected penalty for planning and not implementing is P 2 (>0); the cost of planning, known at Stage I, is C p (>0); and M is a payoff to the firm from implementation of its plans. Note that M is a function of both the costs and benefits of implementing the planning at Stage II. Since M is not known by the firm until Stage II, we refer to the expected value of this payoff, E(M), which represents what, at Stage I, the firm expects its payoff will be at Stage II. In the absence of government intervention, E(M) is the product of the probability that M will be positive and the potential positive value of M. Footnote 12 In the presence of government intervention, E(M) is a function of the values of the alternative plans that the firm produces and the probability for each plan that the government would force the firm to implement that plan.Footnote 13 Taking all of these factors together, the firm makes a decision at Stage I based on P 1, P 2, C p, and E(M), and at Stage II based on P 2 and M.

Figure 3. Regulated Entity's Decision Framework Under Management-Based Regulation Stage I Stage II Payoffs

What implications can be derived from these assumptions for regulatory design? Using a model of optimal deterrence for purposes of analysis (Reference BeckerBecker 1968; Reference Polinsky and ShavellPolinsky & Shavell 1984), four scenarios are possible under the decision framework presented in Figure 3, ranging from no mandate needed to a mandate needed for both the firm's planning and its implementation of its plan.

1. Scenario A: No mandate necessary

First, a subset of cases exists where, even if fines were set to 0, firms would still “regulate” themselves. That is, where E(M)−Cp>0 and M>0, firms will voluntarily develop and implement plans to produce social outputs. This is the theory underlying voluntary environmental management programs, such as the European Commission's Eco-Management and Audit Scheme (EMAS) program (Reference OrtsOrts 1995). Under such programs, firms develop planning to evaluate where waste occurs in the manufacturing process on the premise that pollution can be indicative of inefficient processes. European regulators have established guidelines for effective environmental management but have not required firms to adopt management practices that meet these guidelines. Interestingly, numerous firms have voluntarily complied with these guidelines, highlighting the possible role for management-based approaches to industry self-regulation (Reference Gunningham and ReesGunningham & Rees 1997).Footnote 14

2. Scenario B: Mandate necessary at planning stage only

Second, where E(M)−Cp<0 and M>0, the state needs only to enforce at the planning stage (i.e., set P1>0 and P2 to 0). This is the case where the costs to the firm of planning exceed the expected net benefits (E[M]) from implementation, but the net benefits (M) will turn out to be greater than zero. Thus, if the regulator is successful in pushing the firm to study the problem, the firm will then “self-regulate,” implementing the plan because its interests coincide sufficiently with those of the public. The incentive structure can be in the form of either punishment for unsatisfactory planning or subsidies for satisfactory planning (e.g., through provision of training and expertise).

The TURA law introduced in Part I is an example of a law based on the theory of Scenario B. TURA not only aims to reduce the use of toxic chemicals in the state without imposing any new technology-based or performance-based standards, but it also only requires firms to develop plans aimed at identifying opportunities for toxics reduction—not actually to implement these plans. Indeed, the Massachusetts environmental protection agency is explicit in stating that TURA's “planning process is designed to help facilities identify opportunities for toxics use reduction that make economic sense for them” (Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection 2002:1). Notwithstanding the lack of an implementation mandate, many firms do carry out their plans. Indeed, one study has shown that about 80% of the surveyed facilities reported implementing at least some toxic use reduction projects that they identified through the planning process (Reference Becker and GieserBecker & Gieser 1997).

3. Scenario C: Mandate necessary at implementation stage

Where E(M)−Cp>0 and M<0, the state needs only to enforce implementation (i.e., set P1 to 0 and P2>0). This is the case where the firm expects gains from planning and implementation, but upon planning finds that implementation is more expensive than expected or that the private benefits are smaller than expected. In this scenario, the firm plans without government incentives to do so but then needs to be pushed to follow through. In some of the cases where firms have implemented environmental management systems in anticipation of savings from more efficient processes, for example, firms may find new ways to reduce pollution where the sum of the private benefits and public benefits outweigh private costs, but where private costs outweigh the private benefits. In this context, the challenge for the regulator is not to encourage the private sector to research ways to advance public goals, but to harness what the private sector has already invested in learning.

If there is a mandate and enforcement at the implementation stage, it is important to note that this changes the value of E(M). In the absence of government intervention, a firm will implement a plan only if M>0. The presence of government intervention means that a firm may be forced to implement a plan even if it is at a loss to the firm. It is therefore reasonable to assume that government involvement at the implementation stage shifts E(M) down.Footnote 15 This may have the perverse outcome that with government only mandating implementation of plans that firms voluntarily develop, firms will avoid doing the planning they would have otherwise done—if only to avoid being forced to implement costly plans. Furthermore, where a firm identifies through its planning process a set of actions that would be beneficial to the public but would be costly to itself, it will have the incentive to hide this information from the regulator. Thus, if an implementation-only mandate is to have any chance of changing firms’ behavior, government will need to ensure that firms’ planning processes are transparent. This will mean that to be effective, an implementation mandate will need to be accompanied, at a minimum, by some type of planning requirements—even if they are aimed only at making firms’ planning transparent.

4. Scenario D: Mandate necessary at planning and implementation stage

Where E(M)−Cp<0 and M<0, the regulator needs to enforce at both the planning and implementation stages. This is likely the most common scenario and combines the challenges of Scenarios B and C. In Scenario D, the firm lacks the appropriate incentive to engage in a sufficient degree of planning on its own and also lacks the incentive to implement the actions that result from a planning process. For example, in the area of food safety, even though firms have some incentive to maintain a safe production process, the difficulty of tracing food contamination to a specific processing plant means that firms will not have sufficient incentives to plan adequately nor to implement all the appropriate steps needed to provide optimal protection against food contamination. HACCP therefore includes both planning and implementation mandates. Indeed, the effect of HACCP has been to impose significant planning costs on firms as well as implementation costs, such as physical and human capital investments (Reference GallGall 2000).

5. Summary

When firms have incentives to adopt and implement systematic management practices even in the absence of government enforcement, management-based regulation may not need to be regulation at all but a voluntary option for firms, such as is currently the case with environmental management systems adopted under the criteria set forth in EMAS or the ISO 14001 series of voluntary standards (Scenario A). In all other settings (Scenarios B, C, and D), government needs to possess the capacity to monitor planning or implementation, or both, in order for management-based regulation to be effective. Table 1 summarizes the incentive structure characterizing each of the scenarios and the corresponding options for mandating planning, implementation, or both.

Table 1. Incentives and Mandates Under Management-Based Regulation

Management-based regulation, even when it is a better option than performance-based or technology-based regulation, will succeed only if government is capable of sufficiently increasing the magnitude of P1or P2, either by increasing the probability of detecting noncompliance or by increasing the adverse consequences for noncompliance. In Scenario B, the regulator will need to focus its efforts toward increasing the expected penalties at the planning stage rather than at the implementation stage. It may be satisfactory for the regulator simply to possess the capacity to evaluate the expense and effort that the firm took in examining certain processes. Thus, for example, if the firm hires individuals with particular training and demonstrates that it has studied the causes of certain types of hazards in its production process, then an improved set of outcomes is likely to follow.

By contrast, in Scenarios C and D such a regulatory approach would fail. In Scenario C, the firm will invest in the planning regardless of government intervention. A regulatory regime aimed just at the planning stage would fail to improve private behavior. The regulator must focus on the implementation stage. Of course, this does not mean that the planning stage may be disregarded, because government enforcement of implementation gives firms an incentive to obfuscate the conclusions that result from their plans. However, in contrast to Scenario B, the regulator can assume that the firm will invest enough in a rigorous planning process. The regulator therefore needs (1) the planning process to be transparent enough so that the regulator can independently evaluate the data,Footnote 16 (2) the technical capacity to evaluate the data and determine whether the plan the firm proposes is consistent with the data,Footnote 17 and (3) the capacity to evaluate implementation of the plan.Footnote 18

Scenario D, which is a combination of Scenarios B and C, is the most demanding scenario for the regulator, requiring an evaluation of firms’ planning and implementation. An inability to monitor and enforce either planning or implementation will likely compromise policy objectives. If the regulator is unable to evaluate the planning process, then the resulting plans that the firm implements will likely be plans that minimize the firms’ costs rather than maximize net societal benefits. If the regulator is only able to evaluate the planning process, firms cannot be expected to implement costly plans, even if such plans would deliver substantial social benefits.

In summary, designing an effective management-based regulation will depend in the first instance on the types of mandates the regulation imposes. A key consideration in deciding whether to mandate (and enforce) planning, implementation, or both will be the degree of overlap between firms’ private interests and society's needs. Where there is substantial overlap, all that government may need to do is to require firms to engage in a planning process, since firms can be expected to implement their own plans to serve their own interests even if not to advance public goals. In other (and perhaps most) cases, this overlap will not be sufficient to ensure that firms implement their own plans. In these cases, government will need to mandate planning and implementation and to develop appropriate methods for monitoring and enforcing both.

B. Meta-Management Design Choices

In addition to deciding what to mandate, regulators face other choices when designing management-based regulations. One of these relates to how prescriptive government should be in directing firms’ management practices. Another choice is whether to require firms to submit plans for government review and approval before implementation. A final choice concerns methods for monitoring implementation, with options ranging from record-keeping provisions to requirements for third-party auditing and certification. These choices arise in order to address what is effectively a principal-agent problem between the government and the regulated entity.Footnote 19

With management-based regulation, the government takes on the role of what might be considered a “meta-manager,” seeking to guide and motivate firms to order their own economic activity in a way that is more aligned with social interests. Yet because regulated firms can be expected to have interests at odds with the government's goals, and because they have an informational advantage, the regulator finds it necessary to develop ways to induce and control firms so that they manage themselves in ways more aligned with social goals. These ways include the degree of specificity in the regulator's prescribed management practices, the degree to which the regulator shares in the development and approval of firms’ management plans, and the type and stringency of the regulator's monitoring of firm compliance.

1. Specificity of required management practices

A critical issue in the design of a management-based regulation program is the specificity of the requirements for the planning process dictated by the regulator. Management-based regulations can range from simple requirements calling on firms to develop plans to highly detailed requirements specifying criteria for adequate planning, as well as requirements for firms to monitor their performance and correct departures from their plans. For example, the Massachusetts pollution prevention statute is quite general in its core provision. It requires that firms simply include in their plans “a comprehensive economic and technical evaluation of appropriate technologies, procedures and training programs for potentially achieving toxics use reduction” (TURA 1994 § 11(3)(a)). The state regulations implementing TURA do not get much more specific either, requiring regulated firms to “demonstrate a good faith and reasonable effort to identify and evaluate toxics use reduction options” (310 C.M.R. 50.42(11) 2003).

By contrast, the EPA's risk management regulation is both longer and more specific, providing detailed steps for scenario planning and hazards assessment. Rather than simply requiring firms to identify “appropriate” procedures, EPA is detailed about what kinds of actions should be contained in a firm's operating procedures. For each regulated chemical process, the firm must prepare “clear instructions or steps” that address

(1) Initial startup; (2) Normal operations; (3) Temporary operations; (4) Emergency shutdown and operations; (5) Normal shutdown; (6) Startup following a normal or emergency shutdown or a major change that requires a hazard review; (7) Consequences of deviations and steps required to correct or avoid deviations; and (8) Equipment inspections. (Chemical Accident Prevention Provisions 2002, 40 C.F.R. § 68.52)

The EPA regulations also mandate that firms train their employees in these operating procedures and that “[r]efresher training shall be provided at least every three years, and more often if necessary” (Chemical Accident Prevention Provisions 2002, 40 C.F.R. § 68.54).

A related issue is whether technology-based or performance-based standards should play a role in parts of what is otherwise an overall management-based regulatory strategy. While any discussion of regulatory instrument choice proceeds by analyzing a set of ideal types, in practice an overall regulatory strategy sometimes consists of a combination of different instruments deployed to address a common problem. A management-based regulatory regime may be complemented with a set of technological mandates or performance targets. For example, with respect to food safety, the USDA complements its HACCP regulation with a sampling and testing regimen that contains performance standards for levels of E. coli and Salmonella (USDA 1996).Footnote 20 The Department has also recently proposed a set of additional performance standards for pathogen levels in ready-to-eat meats (e.g., cold cuts) that would overlay the agency's general HACCP requirements (USDA 2001). These performance standards are considered inadequate by themselves to provide the main strategy for regulating food safety, since testing regimens rely on a limited number of samples and in any case meat must some-times be shipped into distribution earlier than lab results can be obtained. But management-based regulation may be used in conjunction with performance or technology standards in order to compensate for limitations in the effectiveness of the latter, more conventional forms of regulation.Footnote 21

Recognizing that management-based regulation can become highly specified, and even accompanied by technology-based or performance-based standards, demonstrates a tension in designing effective management-based regulation. On the one hand, the parameters that government selects may be so imprecise that it may prove to be too difficult for enforcers to monitor firms’ compliance in a nonarbitrary way. For example, it may not be clear to either the regulated entity or the inspector what an “appropriate” procedure is for reducing toxic chemicals. Such cases of imprecision may also make it more likely that at least some inspectors will become captured by the regulated entity and exploit ambiguities in the rules to the firms’ advantage. On the other hand, it may be tempting for government policymakers to respond to these concerns by making planning parameters very specific, and even to combine them with technology or performance standards. If government does so, then it risks losing the flexibility that is one of the potential advantages of management-based regulation. The challenge for the regulator is therefore to find an optimal level of specificity that points firms in the right direction and enables inspectors to assess whether a firm has a good management system in place, but that also is not too specific that private managers no longer have the flexibility to adapt their practices to the individual conditions of their organizations. Management-based standards that become highly prescriptive may well undermine the potential cost savings that otherwise make management-based regulation attractive. One strategy that regulators have used to address this challenge has been to rely on general parameters in crafting binding management-based rules, but then to issue more specific criteria in nonbinding guidelines (Reference RakoffRakoff 2000; Reference StraussStrauss 1992).Footnote 22

2. Plan Approvals

Another design issue is the extent and type of involvement by the government at the planning stage. In particular, how are plans negotiated between the regulator and regulated? One might imagine several alternatives: (1) the regulator reviews all management plans in advance and the regulated firm must receive preapproval of its plan before implementing it, (2) the regulated firm must submit a management plan to the regulator which the regulator keeps on file but does not preapprove, or (3) the regulator checks to see if the firm has completed the appropriate plan ex post, either during periodic inspections of the firm's facilities or following an accident or incident. For example, with respect to the application of HACCP to the processing of fish, regulators in the United States do not have a preapproval process, but in Canada they do (Canadian Fish Inspection Regulations 2003, 802 C.R.C. §§ 14(1) & 15(6)). We highlight four key factors that are likely to affect how actively the regulator should be involved during the planning process:

• Clarity of criteria for planning. If there is substantial ambiguity over what an acceptable planning process is, or if it is difficult to specify criteria ex ante for what makes a management plan acceptable, then the regulator may find it advantageous to be involved earlier in the process.

• Need for transparency at planning process. As noted above, firms can have an incentive to obfuscate data or to treat the planning process as a paper exercise to avoid the implementation of costly, but effective plans. Early and active involvement by the regulator may increase the chances that firms would engage in meaningful planning and accurate record-keeping.

• Mechanism to subsidize the planning process. Regulators will often develop an expertise in the generic management challenges that regulated parties face. In particular, in Scenario B above, it may be more efficient and effective for the regulator to take on the role of quasi-consultant, effectively giving away its expertise in return for improved management of public goals by the private sector. Such a role may be better served by early involvement in the planning process, such as through a preapproval requirement.

• Government resources. Preapproval of planning does not eliminate the need for subsequent inspections by regulatory agencies and can instead place additional resource burdens on the government. By contrast, reviewing plans only periodically at the time of a regular inspection minimizes the demand on government resources.Footnote 23 The number of facilities covered by the regulation will also undoubtedly matter. Where there are many sites relative to the regulator's resources, the costs associated with a preapproval process will make that option prohibitive. This appears to explain why the resource-starved FDA evaluates plans ex post, whereas the better-endowed Canadian counterpart is able to require preapproval.

In short, there are multiple ways to enforce a planning mandate, ranging from preapproval at the time of the planning or enforcement at some time (potentially a long time) after planning has taken place. The desirability of early involvement depends in part on the needs of the regulated firms for feedback and de facto planning subsidies, as well as the informational needs and capacity of the regulator.

3. Record-Keeping, Inspections, and Third-Party Auditing

Beyond requiring preapproval, there is the question of how to monitor and enforce planning and implementation mandates. To facilitate such monitoring, management-based regulation will typically be accompanied by record-keeping requirements. For example, the FDA requires juice-processing facilities to maintain onsite documentation of their entire HACCP plans, including hazards analysis, testing, and documentation of implementation of procedures, so that the FDA inspectors can “determine whether the HACCP system or systems are properly implemented and effective” (FDA 2001a:6163).

Regulatory agencies also need to decide how frequently to inspect facilities governed by management-based regulation. They can require a continuous or occasional presence at processing locations. For example, USDA inspectors are onsite continuously at meat processing plants, whereas the FDA visits fish processors only once a year. The key variables underlying the choice of how frequently to inspect include (1) the size of the processors (e.g., meat processors are much larger than fish processors, making it much more economical to have a presence there), and (2) the types of actions the regulator is attempting to observe. If the regulatory problem is such that the regulator needs to observe routine practices, such as how clean processing surfaces are kept, an almost continuous presence may be necessary because firms may only implement these practices when the regulator is present. However, if the regulator is trying to observe implementation of costly technologies, such as installation of refrigeration equipment, occasional visits may be more than adequate.

An additional choice is whether the regulator should delegate the inspection function to third-party auditors, allowing firms to choose and pay for their own private auditing services. The Massachusetts TURA program, for example, requires facilities to have their toxic use reduction plans “certified by a [state-authorized] toxics use reduction planner as meeting the department's criteria for acceptable plans” (TURA 1994, § 11(B)). The EPA has experimented with the use of third-party auditors to monitor firms’ implementation of its risk management regulations aimed at preventing chemical accidents (U.S. EPA 2001).

Third-party audits offer several potential advantages. First, they may create incentives for the inspections themselves to be as efficient as possible. Second, if there are economies of scale in understanding the relevant management systems, third-party certifiers specializing in different types of facilities or processes may better capture those scale effects. Finally, third-party auditing can help offset or augment the limited resources of government regulators. For example, as discussed in Part IV with respect to HACCP, the FDA and USDA have very constrained inspection capacities. Even if third-party auditing is voluntary, the availability of such auditing may help the regulatory agency more efficiently allocate its limited inspection resources, since firms’ choices about whether to get an audit may reveal something about the nature of the risk they pose. Firms not choosing to be audited on their own may be assumed to be firms with higher risks, and government inspections of these firms will likely yield greater marginal benefits to society (Reference Kunreuther, McNulty and KangKunreuther, McNulty, & Kang 2002).

The challenge of third-party certification is that it creates another layer of agency problems, a point that accounting debacles in the financial sector have accentuated in recent years. Relative to government inspectors, third-party certifiers probably face incentives to satisfy their clients through at least marginally more lax enforcement. The question for regulatory policy then becomes whether the regulator can work through two layers of agency, determining whether a firm has been compliant and, if not, whether the certifier should have caught the noncompliance.

C. Summary: Designing Management-Based Regulations

The main sets of choices in designing management-based regulation are of two types. The first type is reflected in the choice of whether to mandate planning, implementation, or both. The second type revolves around how the regulator seeks to overcome the principal-agent problems inherent in directing and overseeing firms’ management practices. These two types of choices are interrelated. The decision about what to mandate depends on the nature of the incentives firms already have to plan or implement actions directed at addressing issues of social concern. Yet the nature of these incentives also affects regulators’ choices about how to direct and oversee firms’ management.

To the extent that firms lack adequate incentives on their own to create plans and implement them, they may resist—even in subtle ways—complying with the letter and spirit of any management-based mandate imposed by government. When it comes to planning, some firms will undoubtedly devote as few resources as they can to analysis and will have the incentive to produce plans that minimize the firms’ implementation costs rather than maximize social benefits. The regulator therefore needs to be able to assess whether firms’ planning processes and resulting plans have been appropriately rigorous. When it comes to implementing these plans, firms may have the incentive to avoid costly and effective implementation, so regulators must be able to assess whether firms have made adequate capital investments and are regularly acting in a way that is consistent with their plans.

The options available to the regulator include the development of specific—and more difficult to evade—mandates embedded within the management-based regulation. In addition, the regulator may be better able to ensure the adequacy of planning by requiring government approval of firms’ plans. Finally, the regulator will be better able to ensure effective implementation by imposing suitably detailed record-keeping requirements and instituting inspections or third-party audits. Even so, what makes for “good management” will generally be somewhat open-ended or case-specific, and the greater discretion afforded to firms under a management-based approach to regulation will also inevitably add to the regulator's enforcement challenges.

IV. Assessing Management-Based Regulation

How has management-based regulation performed in practice? The three regulatory programs we introduced in Part I provide a basis for making some initial assessments about management-based regulation and our analysis of its use and design. Each of these regulatory programs—whether to reduce the use of toxic chemicals, avoid chemical accidents, or prevent food contamination—all require firms to conduct analysis and planning directed toward the public goals that stand behind the regulations. The food safety and chemical accident programs also require firms to carry out the plans they develop and to audit themselves to assure compliance with the required management plans.

Each of these three programs also responds to public problems that have the characteristics we outlined in Part II, namely problems for which regulators confront significant difficulties in measuring outputs and where firms are too heterogeneous to make technological standards feasible. In the food safety area, the traditional model of sensory detection of contaminated meat (“poke and sniff”) has proved ineffective at detecting microscopic contamination. The obvious alternative is to take samples from the final product of the handling process and test them at a laboratory, yet results from laboratory analysis take time to achieve, and perishable products sometimes must be shipped out before the results can be received (National Academy of Sciences 1998).Footnote 24 Of course, in the area of chemical accident prevention, no simple laboratory test of any kind has yet to be devised to test for the safe handling and storage of chemicals, and the output to be avoided already has a low probability of occurring.

A most significant challenge in all of these cases comes about from the large number of sources of hard-to-detect risk. Even with substantially greater inspection resources, government agencies would be hard pressed to identify and test for all of the invisible risks of food contamination that can arise in the large number of facilities that process food, or all the potential sources of risk of chemical accidents, or all the ways that pollution prevention could be achieved. OSHA's PSM standard governs more than 25,000 facilities nationwide, and EPA's RMP requirement affects more than 15,000 facilities. Firms themselves will typically know more about the unique risks of their products and processes and are therefore better positioned to judge where and when accident risks are likely to result from their processes.

The large number of firms covered by these regulations by itself suggests that the regulated population is also extremely heterogeneous. As the FDA noted in a recent rule implementing HACCP in the area of fruit juice safety—itself a quite narrow industrial sector—“[e]ven when producing comparable products, no two processors use the same source of incoming materials or the same processing technique, or manufacture in identical facilities” (FDA 2001a:6140). The USDA exercises jurisdiction over producers of products ranging from milk to meat-topped pizza to uncooked ground beef to processed egg products (Reference TaylorTaylor 1997). Even more extensive variation in the types of facilities and processes can be found across the firms covered by regulatory programs aimed at chemical accident prevention and toxic use reduction.

Each of the three regulatory arenas described in Part I encompasses a sweeping array of firms that employ many different combinations of technologies, processes, resources, constraints, and conditions. Inevitably, many firms will have, but the government will lack, an everyday knowledge of how a particular step in the process could go wrong and the likely effects of a change in technologies on the cost and speed of the production line. Firms know something about the vulnerabilities of their personnel and equipment, and they may understand their own processes at a level of detail that allows them to foresee risks that an agency inspector would easily miss. Furthermore, plant conditions are always subject to abrupt changes, and firms are better situated to identify those changes and adapt to them.

The critical question regarding management-based regulatory approaches is whether they can overcome the design challenges outlined in Part III. In many cases, firms will underinvest in safety measures absent government intervention. This typically means that regulators need to monitor firms’ planning in some way and enforce appropriate levels of implementation. In the food safety area, new regulations grant inspectors access to essentially all records related to the HACCP, including the firm's choice of CCPs, its plans of action to ensure that safety is maintained at each CCP, and the records indicating whether the CCP has exceeded the critical limit (Inadequate HACCP Systems 2003, 9 C.F.R. § 417.6; HACCP Training 2002, 21 C.F.R. § 123.10).Footnote 25 Furthermore, regulatory inspectors evaluate the processes that they actually observe during site visits. The same is true for OSHA's and EPA's regulations aimed at preventing chemical accidents and releases.

Do regulators have the capacity to evaluate planning and implementation? The first years of HACCP provide some troubling data. For example, under its main HACCP program, the FDA has been able to inspect fish processors only once a year, examining firms’ plans, their records, and the actual processes associated with a single product line (usually one of the high-risk product lines). Further, in about half of these cases, the product line selected to be inspected is not active at the time of inspection, and the inspection is limited to paperwork review (GAO 2001:17). This inspection process therefore does not reveal the effectiveness of the HACCP plans of noninspected product lines. It also does not directly reveal whether the firm carries out its plan in the various contingencies specified in the plan that do not occur while the inspector is watching. Instead, inspectors must rely on the firm's records of what occurred.

This leads to the question of whether firms will maintain an accurate record of their actions in those instances where damaging information may lead to the agency penalizing the firm.Footnote 26 One critic of HACCP warns that firms have little reason not to falsify records, particularly in the absence of whistleblower protections or other incentives for someone knowledgeable to verify what went on in the production line (Reference LassiterLassiter 1997:444–56). Even if firms are not outright untruthful, they may conclude that they would do themselves little good by including in their plan any hazards that government inspectors are unlikely to spot on their own, particularly if these cannot be remedied cheaply. Since management-based regulatory strategies are designed to incorporate a firm's specialized expertise in its product and processes into its safety practices, the very instances in which a firm's expertise would help it to identify hidden hazards may well be some of the same ones in which the firm has the opportunity and incentive to keep its hazards hidden.Footnote 27

Given the FDA's enforcement regime, what is the overall compliance with HACCP requirements among fish processors? FDA data suggest that three years into implementation of HACCP in this sector of the food industry, a majority of fish processors still have plans that are not in compliance with the agency's HACCP rule (GAO 2001:18).

By contrast, the USDA's HACCP meat and poultry program might seem likely to fare better, since the USDA does not face the same constraints on inspection personnel relative to the number of regulated sites that the FDA has faced. In fact, the USDA maintains a continuous presence at all the meat and poultry plants under its jurisdiction. Nevertheless, concerns have been raised about whether the USDA's organizational capacities to carry out its longstanding poke-and-sniff approach to meat inspection are well-suited to enforcing management-based regulation.

A recent GAO (2002) report critiquing the USDA's HACCP program in the meat and poultry areas highlighted two areas where the USDA has apparently fallen short: human capital and information systems. In particular, evaluation of HACCP planning requires individuals with substantial expertise about potential sources of microbial contamination. Despite the USDA's continuous presence at all the processing plants it oversees, the agency does not appear to have the capacity to ensure that plants are in compliance because the personnel present can only evaluate implementation of a HACCP plan and not the design of the plan itself. For example, officials in the two largest inspection offices (Alameda, CA and Albany, NY) indicated that at their current capacity it would take them up to five more years to review all the HACCP plans for the facilities falling under their jurisdiction (GAO 2002:14). In addition to the undesirability of the short-run situation where firms are using unevaluated plans, this lack of capacity creates two undesirable possibilities in the future: (1) firms will be locked into existing plans until a distant future when the regulator can review new plans, or (2) every time firms change their plans and processes, there will be a multiyear lag before the regulator reviews what the firms plan to do.

The GAO report also highlighted the failings of the USDA information systems. In particular, the report asserted that inspectors had not consistently identified and recorded repetitive violations, “in part, because [the USDA] has not established specific uniform criteria for identifying repetitive violations” (GAO 2002:17). Arguably, part of the reason why such record-keeping is difficult is that, in contrast to technology-based rules, all violations are context-specific. The lack of one-size-fits-all standards makes it difficult to use a one-size-fits-all information system.Footnote 28

Both of these examples highlight a key implication: Management-based regulation requires a very different profile of governmental capacities than other types of regulation. In making any decision about whether a management-based regime will be effective, it is necessary, in part, to determine how the regulator needs to adapt, and then to evaluate whether it has the capacity to do so.

The result of the USDA's enforcement regime has been, as with FDA, a lack of compliance with HACCP requirements. The USDA conducted in-depth reviews of 47 plants in 2000–01 (slightly less than 1% of the total plants it inspects). In 44 of those plants, there were significant violations of HACCP requirements. In 42 of those cases, it was because of an incomplete hazard analysis (GAO 2002:12).