Studies of judicial decisionmaking over the last several decades have significantly increased our understanding of the behavior of the U.S. Supreme Court and the justices who compose it. In an attempt to increase our understanding of courts and of judging more broadly, there recently has been an emphasis on the expansion of comparative judicial research (Reference EpsteinEpstein 1999:1). Such an emphasis will allow scholars to develop truly generalizable theories of judicial decisionmaking that apply to courts beyond the borders of the United States. With this comparative focus in mind, we explore the primary assertions of previous research on appellate court behavior: Judges are affected by their policy preferences, and decisions are made that benefit those preferences. To test our assertions, we analyze the behavior of individuals in two appellate courts: the Supreme Court of Canada in the post-Charter years and the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of the apartheid-era Republic of South Africa. More specifically, we focus on the behavior of the chief justices in panel assignments, exploring the role of tenure, issue, and ideology.

Interest in panel assignments in the United States has been primarily confined to studies of the federal courts of appeal (the only federal courts to hear cases in panels) during the desegregation era. Several studies of possible influences on these assignments discovered that while assignments were thought to be random in most courts, in the Fifth Circuit at least, the chief justice appeared to be influenced by his policy preferences when assigning justices (Reference Atkins and ZavoinaAtkins & Zavoina 1974; Reference Barrow and WalkerBarrow & Walker 1988; Reference HowardHoward 1981). Further, scholars have suggested that while policy preferences may not have an impact in all courts, the panel assignment process could still be classified as nonrandom since considerations of seniority and expertise may influence chief justices (Reference HowardHoward 1981).

Although work on panel assignments has been largely abandoned in recent years,Footnote 1 research on the opinion assignments of U.S. Supreme Court chief justices can provide insight into possible influences on panel assignments as well. The opinion assignment literature has found differences among the chief justices. Thus, while Chief Justice Rehnquist has been found to consider workload factors most prominently (Reference Maltzman and WahlbeckMaltzman & Wahlbeck 1996), earlier chief justices were found to consider their own policy preferences when making opinion assignments—those with similar preferences to the chief justice were more likely to be assigned an opinion (Reference Segal and SpaethSegal & Spaeth 1993; Reference SlotnickSlotnick 1979a; Reference UlmerUlmer 1970). Other factors such as judicial expertise, efficiency, experience, and the importance of the case have also been suggested as possible influences by some of this literature (Reference BrennerBrenner 1984; Reference Maltzman and WahlbeckMaltzman & Wahlbeck 1996; Reference Brenner and HagleBrenner and Hagle 1996; Reference SlotnickSlotnick 1979a). These factors inform our own study of panel assignments—the additional power held by chief justices in our countries of interest. Despite the decreased attention paid to the panel assignment decision in the United States in recent years, we believe this behavior has the potential to significantly affect the outcome of cases. Thus, the factors influencing the chief justice in his assignments need to be explored.

Judging in Comparative Perspective

If we assume that judges are universally drawn from similarly situated populations of elite political actors, we can also assume that some behaviors will be consistently demonstrated across social systems. To test the generalizability of this assertion, analyses must evaluate behaviors across a wide variety of social systems. To explore the assertion that judges will exhibit similar behaviors even in differing polities, we deliberately chose two very diverse countries: Canada and South Africa. Thus, we compare one country with a long, stable democratic tradition beginning a new era of articulated protection of rights and liberties with an authoritarian regime that lacked any pretense of equality among its population. Politically, socially, and economically, these two countries differ dramatically. We argue that if judges exhibit similar behaviors in these two disparate systems, scholars can have greater confidence in the underlying assertions of judicial behavior theory. Moreover, for comparative theory and methodology to develop in public law research, scholars must inevitably include a wide variety of legal systems where differences exist but where the similarities between the courts in each country invite comparison.

We argue that judges, like other political actors, have policy preferences they seek to have adopted by the court in its decisions. Further, we argue that chief justices, in particular, have unique opportunities to shape outcomes. To that end, we chose to study two countries in which the chief justices have greater power than that exercised by the chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. In both Canada and South Africa, the court hears disputes in panels, the membership of which is determined by the chief justice. Chief justices may use panel assignment to appoint like-minded judges in an attempt to influence the ultimate decision of the court. We hypothesize that chief justices in both Canada and South Africa will demonstrate such behavior and assign members to panels in a nonrandom manner.

In both countries included in our study, the high courts sit atop a professionalized judiciary and comprise well-trained legal minds. Judges have secure tenure at both courts, and other political institutions give deference to the courts and their decisions. Moreover, both legal systems have been similarly influenced by their British colonial heritages. Despite the enormous differences in the social structures in Canada and South Africa, if our theories of judging are generalizable, we expect similar factors to influence judicial behavior.

The Canadian and South African Courts

Court History and the Exercise of Power

The Supreme Court of Canada and the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court of South Africa (at least for the time period of study)Footnote 2 both stand at the apex of their judicial systems—they are courts of last resort. Both courts are part of an integrated judicial system and hear appeals for both provincial and federal law. The South African court exists in a mixed legal system based on both the Roman-Dutch civil law heritage, which arrived with the white settlers of the Dutch East India Company in 1652, and the English common law system introduced by the British colonials. Similarly, the Canadian Supreme Court is familiar with both common and civil law as a result of the country's history of English and French settlement. While it is an overstatement to suggest that Canada has a dual legal system (given the dominance of common law), one Canadian province, Quebec, has retained a civil law system. This division within the country has led to the requirement that three of the nine Supreme Court judges on the bench at any given time must come from Quebec.

The South African Appellate Division and the Canadian Supreme Court have experienced varying levels of power. When the Afrikaner National Party ascended to power in South Africa in 1948, bringing with it a devotion to segregation of the races, the courts were originally considered by the opposition to be a harbor of hope (Reference AbelAbel 1995). While the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court did not have the ability to exercise traditional powers of judicial review, it did have the capacity to declare acts of Parliament and government officials ultra vires. Footnote 3 The opposition saw the courts as a possible avenue to stem the National Party's efforts to obliterate the few rights remaining to people of color, and in a number of cases in the early 1950s the Appellate Division did rule against the government. These rulings brought the court into direct conflict with the National Party regime. After several exchanges, the government responded by increasing the size of the court from six to 11 and proceeded to pack the court with Afrikaners. Further, in 1956, a newly expanded Senate enabled the Parliament to add a clause to the constitution that specifically denied South African courts the power of judicial review.Footnote 4 When this new clause was challenged, the newly expanded Appellate Division sided with Parliament ten to one.Footnote 5 From that point, the Appellate Division remained deferential to the government in most of the major disputes before it (Reference HaynieHaynie 2003).

The Canadian Supreme Court, by contrast, became increasingly powerful in the latter half of the twentieth century. In 1949, the court formally became Canada's court of last resort when appeals to the British Judicial Committee of the Privy Council were finally eliminated. In the decades following, the court gained both power and prestige. Although Canada subscribed to the British tradition of parliamentary supremacy, the Canadian court was able to exercise a limited form of judicial review. Canada's federal structure meant the court was often asked to rule on the powers of the provincial and federal governments—keeping each within its own sphere of influence by declaring actions ultra vires if necessary. The passage of the Constitution Act in 1982 increased this power for the courts through its entrenchment of constitutional supremacy and its introduction of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Canada's own bill of rights. The Canadian Supreme Court now has final responsibility for interpreting the constitution, including the ability to strike down laws and actions it deems inconsistent with the constitution. The court enjoys the full power of judicial review and, with it, increased policymaking power. According to Chief Justice Lamer, “[t]here is no doubt that [with the adoption of the charter] the judiciary was drawn into the political arena to a degree unknown prior to 1982” (Reference Morton and KnopffMorton & Knopff 2000:13).

The Courts' Cases

The cases analyzed here are drawn from the published decisionsFootnote 6 of the South African Appellate Division from 1950 to 1990Footnote 7 and of the Canadian Supreme Court from 1986 to 1997.Footnote 8 The Canadian Supreme Court and the South African Appellate Division hear appeals of civil and criminal cases with procedural and substantive challenges, based on both common law and statutory grounds (Reference DugardDugard 1978:10–13, 280–7; Reference McCormickMcCormick 1994). A large portion of each court's docket is composed of criminal cases. The South African court also sees a heavy concentration of economic cases but only a small but increasing number of civil liberties cases. The agenda of the Canadian Supreme Court has undergone a shift. While about 50% of the court's issue agenda was composed of tax cases and ordinary economic disputes in the 1970s, this was reduced to less than 10% by 1990 (Reference EppEpp 1996:772–3). Instead, civil liberties and civil rights cases increased from barely 10% in the 1970s to comprise about 60% of the court's docket in the 1990s (Reference EppEpp 1996:772–3).

The path these cases take to each court differs. In South Africa, appeal is a matter of right, significantly limiting the discretionary control of the court over its docket. Judges on the lower courts are responsible for granting leaves to appeal, but leave should not be granted unless there is a reasonable likelihood that the appellant will prevail. Thus, although the Appellate Division must accept cases that the lower court has granted leave to appeal, these cases should be those involving some controversy. Parties denied leave can appeal that denial to the Appellate Division, which can vote to grant the leave despite the lower court's refusal.Footnote 9

In Canada, the Supreme Court has wide discretionary power on which cases it chooses to hear. Applications for leave to appeal are heard by a panel of three judges and decisions are made by a majority vote. Still, “appeals of right” do exist in Canada for some criminal casesFootnote 10 and continue to make up about one-fifth of the Canadian court's agenda (Reference McCormickMcCormick 1994:82).

Court Structure and Judges

The Appellate Division of South Africa consists of a chief justice and a number of judges of appeal. In 1950, the first year of this study, the court consisted of six judges of appeal. By the end of the study (in 1990), there were 18 judges of appeal. However, we note that statutory provisions allow the chief justice occasionally to appoint acting judges of appeal for short periods (from a few months to a few years) to serve during illnesses, absences, or interim periods between appointments. By contrast, the Canadian Supreme Court has consisted of nine members, including the chief justice, since 1949.

Judges on the South African Appellate Division and the Canadian Supreme Court are chosen by the Prime Minister after consultation with the Minister of Justice. In South Africa, the chief justice has significant input on appointments. The Canadian Prime Minister's choice is constrained by the requirement that three members of the Court must come from the province of Quebec to ensure that the court will have members who are familiar with Quebec's civil code. Besides the three seats for judges from Quebec, three seats on the Canadian Court are typically designated for judges from Ontario, the most populous province, while the remaining three seats are shared by judges from the western and Maritime provinces. Only one female judge sat on the Canadian Court until 1987. She was joined by two others by 1989. This number decreased to two in 1991 and remained there until 2000, when it again increased to three. The South African Appellate Division did not have any female judges during the time period of interest, and no judges of color served on either court during the years included in the study.

Judges serve on the South African Appellate Division until retirement at age 70 and on the Canadian Supreme Court until age 75. Both the Canadian and South African constitutions allow Parliament to remove a judge on grounds of incompetence or misbehavior, but no judge has ever been removed in this manner in either nation (Reference DugardDugard 1978:10; Reference PittsPitts 1986:64; Reference McCormickMcCormick 1994:119).

For years in both Canada and South Africa, the most senior judge traditionally was elevated to the position of chief justice when the seat was vacated. A judge's first language was also considered in making the appointment. However, these conventions have been violated in both countries. In South Africa, the seniority norm was violated initially by the National Party's 1957 appointment of Afrikaner H. A. Fagan, ignoring the most senior Appellate Division judge, O. D. Schreiner, who had opposed the National Party's machinations to remove mixed-race voters in the Cape. Subsequently, seniority became one of a number of considerations rather than the sole criterion. In Canada, Prime Minister Trudeau first violated the seniority tradition by appointing a junior member, Bora Laskin, chief justice in 1973.Footnote 11 Trudeau violated the language tradition in 1984, when he appointed Brian Dickson as chief justice instead of the most senior French judge on the court. However, the elevations of Antonio Lamer in 1990 and then Beverley McLachlin in 2000 suggest that more recent prime ministers have elected to observe the conventions in Canada.

The Use of Panels

Unlike their American counterparts, judges on these courts of last resort do not have to sit en banc to hear cases. Instead, judges may decide cases in panels. Indeed, the South African Appellate Division has done so on all but three occasions during the time period of interest. On the Appellate Division, the quorum is five for civil cases and three for criminal cases, although criminal cases considered particularly complex may be assigned to a five-judge panel. The Canadian Supreme Court sits as a panel of five or seven, or as a full Court of nine to hear cases. The most common panel size appears to be seven,Footnote 12 despite an apparent preference by recent chief justices to have more cases heard by the full court (Reference Greene, Mancuso, Price and WagenbergGreene 1994; Reference McCormickMcCormick 2000).

In both countries, the chief justice of the court assigns judges to panels. Very little is known about the panel process itself. For Canada, it appears that the panel assignment is made several weeks before the case is heard—usually after the court has received all submissions in the case. In South Africa, all panel assignments are made before the beginning of the session. Only urgent cases, three to four per year, are added after the close of the roll. However, in both countries, the assignment decision is not announced publicly until the day the case is heard.Footnote 13

There is speculation in South Africa that various chief justices have manipulated their panel assignments to maximize the likelihood of decisions that are closest to their preferred policy positions or their own conceptions of good policy. Reference ForsythForsyth (1985) argues that Chief Justice Centlivres (1950–1957) intentionally segregated those on the court before its expansion in 1955 (the “first team”) and the six Afrikaner judges appointed during its expansion (the “second team”). He also argues that Chief Justice Steyn (1959–1971) guided the increasing influence of Afrikaners on the Court through his panel assignments.Footnote 14 More recently, it was alleged that Chief Justice Rabie (1982–1989) handpicked more conservative panels for the state of emergency cases heard by the court in the late 1980s to ensure government victory (Reference EllmannEllmann 1992).

In Canada, the few studies addressing possible influences on panel assignments rely mainly on anecdotal evidence. Reference McCormickMcCormick (1994) describes one chief justice from the 1950s purposely leaving a particular judge—one who disagreed with his view of the law—off panels where this view was at issue. However, McCormick suggests that this action was “exceptional” and unlikely to occur today (1994:205). Reference Greene, Mancuso, Price and WagenbergGreene (1994) agrees, based on interviews with different judges, that while chief justices in the 1950s were known to stack panels with judges sharing their opinions, such practices no longer occur.

Comparative Inquiry and Theory Building

One of the basic questions facing students of judicial behavior remains: Why do judges make the choices that they do? In American courts, this question has traditionally been explored through individual voting behavior via the attitudinal model (Reference Rohde and SpaethRohde & Spaeth 1976; Reference Segal and SpaethSegal & Spaeth 1993; Reference Spaeth and SegalSpaeth & Segal 1999). Judges are presumed to be rational decision makers with specific policy preferences. Though the law and the facts are not irrelevant in the decisionmaking calculus, interpretation of the law and the facts is presumed to be affected by personal preferences. Given that we argue that judges are similar across systems, how can we explore the hypothesis that judges act to further their own policy preferences?

We argue that the assignment of judges to panels provides an opportunity to explore this hypothesis across our two systems. Specifically, we argue that it is important to determine whether South African and Canadian chief justices eschew the advantage of the potential power of panel assignment to further their own preferences or utilize this power to manipulate panel composition and potential outcomes. What does, in fact, influence their panel assignments? Do different factors have a different influence in each country? As mentioned above, we believe answers to these questions are important because the composition of panels may significantly impact—even determine—the outcome of cases. More important, this analysis can provide support for the underlying theoretical assertion of judicial behavior research that judges are affected by nonlegal factors in their choices.

Hypotheses

Both the chief justice of the South African Appellate Division and the chief justice of the Canadian Supreme Court are considered “first among equals.” Indeed, their ability to assign members of the court to panels provides additional power not possessed by the U.S. Supreme Court chief justice. What affects the panel assignment choice? This section outlines some possible influences on a chief justice's decision.

Because we argue that judges prefer to see their own perceptions of good policy adopted, the hypotheses expect chief justices in each country to use their leadership resources to influence panel composition rather than to assign randomly. Thus, assignments are expected to be at least partially dictated by the policy preferences of the chief justice. Research on the U.S. Supreme Court has demonstrated empirically that judges' behavior is motivated, in large part, by their individual attitudes or judicial philosophies (Reference Rohde and SpaethRohde & Spaeth 1976; Reference Segal and SpaethSegal & Spaeth 1993; Reference Spaeth and SegalSpaeth & Segal 1999). And research on the U.S. chief justice's opinion assignments suggests that ideology plays a role in this behavior: those whose preferences are more closely aligned with the chief justice will be assigned to author opinions (Reference Segal and SpaethSegal & Spaeth 1993; Reference UlmerUlmer 1970). Opinion and panel assignments may provide similar opportunities for policy-minded chief justices, and thus both behaviors may be affected by similar variables. That is, chief justices may be more likely to assign to panels individuals whose preferences are more closely aligned with their own. As detailed above, several researchers have investigated the possibility of this type of behavior on the U.S. Courts of Appeals during the desegregation era. These studies find some evidence of the chief judges of the Fifth Circuit gerrymandering panels (Reference Atkins and ZavoinaAtkins & Zavoina 1974; Reference HowardHoward 1981; Reference Barrow and WalkerBarrow & Walker 1988). Thus, judges with policy preferences that the chief justice assumes to be closer to that of his own should be more likely to be assigned to panels.

Operationalizing policy preferences requires that the variables be reliable and valid across both systems. We believe that despite the systemic differences between Canada and South Africa, it is nonetheless feasible to create a valid and reliable measure of policy preferences. First, policy preferences indicate a tendency to support particular outcomes in particular issue areas. For U.S. courts, this has been measured as support for or against the underdog. However, including support for all those classified as underdogs in the United States would not be appropriate here because certain issue areas are not comparable across countries. For example, cases supporting government regulation of businesses are generally coded as supportive of the government as the underdog versus businesses as the upperdog. But coding support for the South African government's regulation of a segregated commercial enterprise is obviously not comparable to government regulation in Canada. Instead, we argue that support for those accused of crimes can be used as a comparable measure. Measuring judicial support for the accused in Canada and South Africa should similarly distinguish attitudes among judges because the salience and direction of outcome in this issue area translates across countries. For both countries, these cases involve the social control activities of the state (Reference ShapiroShapiro 1980). Individuals accused of violating society's rules are universally less sympathetic to the general population. Evaluating a judge's sympathy for these individuals may generally measure a judge's support for procedural or substantive due process, the issues at bar in criminal disputes in both countries.Footnote 15 Second, while measures of judicial policy preferences based on support for the criminally accused are not completely interchangeable with measures based on other types of issues, greater support for procedural or substantive due process translates to more egalitarian or liberal attitudes in both countries.Footnote 16 Each judge's policy preference is operationalized as the percentage of votes he or she casts in favor of the accused in criminal cases. The absolute value of the difference between each judge's ratio of pro-accused decisions and that of the chief justice is then calculated.Footnote 17 We hypothesize that the closer the judge's score is to that of the chief justice, the more likely he or she will be assigned to a panel.

While we assert that chief justices consider policy preferences in all cases, they may be particularly attentive in cases involving more politically salient issues (Reference RohdeRohde 1972; Reference SlotnickSlotnick 1979a; Reference Maltzman, Spriggs and WahlbeckMaltzman, Spriggs, & Wahlbeck 2000). Workload pressures may require the chief justice to distribute panel assignments fairly evenly. The opinion assignment literature has found that the chief justice attempts to equalize the judges' workload when assigning opinions (Reference Maltzman and WahlbeckMaltzman & Wahlbeck 1996; Reference Maltzman, Spriggs and WahlbeckMaltzman, Spriggs, & Wahlbeck 2000). Some of this same pressure may motivate a chief justice's panel assignments.Footnote 18 If chief justices do, in fact, assign judges to panels nonrandomly, we would expect them to reserve like-minded judges for the more salient issues. Thus, we also include an interaction between the proximity of the policy preferences of each judge to the chief justice and the presence of a salient issue. We expect those closer to the chief justice's policy preferences to be more likely to be selected for cases involving issues salient to the public, the government, and the judges themselves.

In Canada, this was operationalized as the presence of a Charter of Rights and Freedoms issue, since these types of civil rights or liberties issues (a subset of the total civil rights and liberties issues heard by the court) were expected to be most salient.Footnote 19 The charter involves fundamental issues such as equality rights, language rights, and the rights of criminal defendants. Litigation under the charter has impacted electoral, legislative, and administrative politics (Reference Morton and KnopffMorton & Knopff 2000). Thus, these cases tend to receive the most attention from the media, the public, and the court itself—they are the “high profile and headline-grabbing” cases (Reference McCormickMcCormick 2000:109; Reference Morton and KnopffMorton & Knopff 2000).

In South Africa, operationalizing salient issues appears more difficult because there were no constitutionally delineated rights and liberties in that country during the period examined. Nonetheless, as in many countries with parliamentary supremacy and no formal bill of rights, there are certain due process protections via the common law and statutory delineation. The South African courts recognized certain protections for individual liberties, derived from the Roman–Dutch legal traditions and the English law. Therefore, individuals brought challenges when speech, religion, press, association, and even equality were limited. And rights of the accused were also recognized.Footnote 20 Attentive publics were particularly cognizant of the rights and liberties cases (Reference AbelAbel 1995; Reference Corder and JamesCorder 1987, Reference Corder and Corder1989; Reference DavisDavis 1987; Reference DugardDugard 1978; Reference Dugard, Haysom and MarcusDugard, Haysom, & Marcus 1992; Reference WacksWacks 1984). Thus, in both countries, our measure of salience includes the types of civil rights and liberties cases that tend to attract the attention of the public, the elite, and the regime.

While attitude compatibility is expected to be one of the main influences on a chief justice's assignment decision, other factors are expected to constrain his choice. Some research on the opinion assignments of chief justices of the U.S. Supreme Court has found that more experienced judges are more likely to receive opinion assignments than their junior colleagues (Reference Johnson and SmithJohnson & Smith 1992; Reference Rubin and MeloneRubin & Melone 1988; Reference Scheb and AilshieScheb & Ailshie 1985; but see Reference Bowen and SchebBowen & Scheb 1993; Reference SlotnickSlotnick 1979b). Chief justices are expected to give junior judges time to acclimatize to their new, perhaps overwhelming, role. Indeed, Chief Justice Hughes is quoted as saying, “[t]he community has no more a valuable asset than an experienced judge. It takes a new judge a long time to become a complete master of the material of his Court” (Reference Bowen and SchebBowen & Scheb 1993:399). And Chief Justice Stone is said to have thought that “a new judge beginning the work of the Court should be put at his ease in taking on the work until he is thoroughly familiar with it” (Reference Bowen and SchebBowen and Scheb 1993:399).

These same sentiments may motivate panel assignments, with chief justices preferring to assign more senior and experienced judges to panels. However, the differences between opinion and panel assignments might also lead to a different expectation. Opinion assignments are a more significant delegation of power. The individual assigned to craft the opinion has the opportunity to shape the specific language of the policy the court has adopted. Opinions can be shaped to restrict the applicability of the outcome or to broaden its significance in the resolution of future conflicts. Merely participating in a panel, however, should not require the same experience as writing the opinion, and any one individual should not have as significant an impact on the outcome of the case. As a result, chief justices may feel less inclined to disproportionately assign senior judges to panels. Indeed, workload pressures may require chief justices to distribute a significant number of panel assignments to junior judges. They may not have the luxury of granting these judges a “transition period” during their early years on the bench.

Therefore, although seniority may affect panel assignments, we do not have firm expectations for the performance of this variable. While following some of the opinion assignment literature would lead one to hypothesize that senior judges may be assigned to panels more frequently, it is also possible that the chief justice will assign junior judges more frequently to panels. Although we lack a strong hypothesis, we expect that more junior judges may be more likely to be impaneled than senior judges for cases as a whole.

However, while workload pressures may result in junior judges being assigned to as many or more cases than senior ones, these cases may be the less complex or less salient ones. Chief justices may want to reserve their more experienced colleagues for the most salient cases—cases that are likely to be important to a wider audience and that may benefit from the higher skill levels of senior judges.Footnote 21 Thus, we anticipate that more senior judges will be more likely to be assigned to a panel hearing a salient civil rights or civil liberties case. To test this hypothesis, we include in our model an interaction between seniority and these kinds of civil rights and liberties cases. We measure seniority as the number of years a judge has served on the court at the time of his or her selection to a panel. The civil rights or civil liberties cases included in the interaction are the same as those detailed above for the interaction with the policy preferences variable.

Much of the opinion assignment literature has focused on the effect of freshman judges in particular. This literature emphasizes a “transition time” that freshman judges need to acclimatize to their new position (Reference Brenner and HagleBrenner & Hagle 1996; Reference Maltzman, Spriggs and WahlbeckMaltzman, Spriggs, & Wahlbeck 2000). Because these judges may be assigned to panels differently from other junior judges, we also include a variable measuring whether the judge in question was a freshman on the Court (within their first year of appointment).Footnote 22 While junior judges as a whole may not experience the benefits of a “transition period,” chief justices may treat new appointees differently. In addition, their recent ascent to the court may make them unavailable to hear cases arriving from lower courts on which they recently served. Thus, we expect freshman judges to be assigned less frequently to panels.

The Models

We use multivariate models to determine the factors influencing the composition of panels in Canada and South Africa. Since the dependent variable is dichotomous, we estimate conditional logit models. Conditional logit must be used rather than logit to take into account the nature of our data. The choices of judges to sit on a panel are interdependent—the selection of one judge affects the probability that subsequent judges have of being selected. Conditional logit can estimate the likelihood of a judge being placed on a panel while accounting for the likelihood of the other available judges being placed on that panel (Reference Maltzman, Spriggs and WahlbeckMaltzman, Spriggs & Wahlbeck 2000; Reference LongLong 1997).Footnote 23

We coded all published cases from 1986 to 1997 for Canada and from 1950 to 1990 for South Africa.Footnote 24 For every panel, we created a variable for each judge sitting on the court when the case was heard. Thus, for the dependent variable, each judge received a (1) if he or she participated in a case, that is, if he or she was selected for the panel. A judge received a (0) if he or she was on the bench but did not participate, that is, if he or she could have been picked but was not. This allows for the maximum likelihood esti-mations assessing the chief justices' choice.Footnote 25 By constructing the database in this manner, we could consider characteristics of both the case and the judges when determining influences on the chief justice. Further, the estimates reflect the influences on the assignment of any particular judge with reference to all of the others.

We first ran the model for each country individually. We then ran the full model (Canada and South Africa) with interaction terms between each of our independent variables and our country control. The results should indicate any differences in the influence of independent variables across countries.Footnote 26

Results

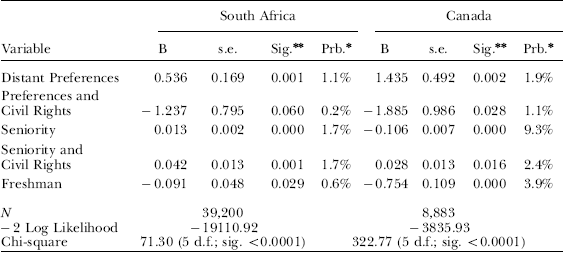

Table 1 presents the results for the model run separately for South Africa (N=39,200) and Canada (N=8883).Footnote 27 The results suggest that even in systems as disparate as Canada and South Africa, similar behaviors are evident in the panel assignments of the chief justices. The coefficients for the conditional logit analyses indicate that many of the variables are significant and in the predicted direction. The overall models are significant at the 0.001 level. We calculated the probability changes listed for a standard deviation increase in the variable of interest holding all other variables at their mean.

Table 1. Conditional Logit Analysis of the Hypothesized Determinants of Panel Assignments in the South African and Canadian Supreme Courts

* Change in probability. For each set of computations, the variable of interest was increased by one significant deviation while holding all other variables at their mean.

** Level of statistical significance. Based on one-tailed tests for variables in the expected direction.

The variable measuring ideological distance between the chief justices and every sitting judge on their court does appear to have the same effect in each country, but it is in an unexpected direction. For our full range of cases, each country's individual results suggest that the chief justice is actually significantly more likely to select individuals who are further from the chief justice ideologically (p<0.005). Why would the chief justice more often assign judges with whom he disagrees to panels? In Canada, at least, this disparity may be influenced by the chief justice's inclination to assign himself to fewer panels, preferring to participate in en banc hearings (an option possible in Canada but not South Africa). Thus a judge with identical ideology is left off a panel frequently. For both countries, it is also possible that workload pressures require the chief justice to use colleagues with distant preferences for cases as a whole.

However, this assignment disparity does not eliminate ideological considerations by the chief justice. While ideologically distant judges may be assigned to more cases, those closer to the chief justice may be assigned disproportionately to the more salient cases. The results in Table 1 suggest that this may indeed occur. For cases involving salient civil rights and liberties issues, the Canadian and South African chief justices are more likely to assign judges with similar preferences (Canada, p<0.05; South Africa, p=0.06). These results suggest that chief justices may be saving judges with close policy preferences for particular cases. Thus, chief justices may prefer to assign judges with close policy preferences but may be unable to routinely do so across all cases.

The seniority variable does not appear to have the same effect in both countries. In South Africa, senior judges generally are more likely to be placed on panels (p<0.001), while in Canada, junior judges are more likely to be selected (p<0.001). We did not have a strong expectation for this variable's effect, and these results do not help settle the question of influence. It may be that workload pressures are stronger in Canada due to the larger panel sizes (five and seven judges in Canada versus three and five in South Africa) and, therefore, junior judges are pressed into service more often. However, interestingly, in Canada, as in South Africa, junior judges are not more likely to be assigned to the more salient cases (Canada, p<0.05; South Africa, p<0.001). Unable to focus on experience in every case, the chief justice may save his more experienced judges for the most important cases before the court.

The related variable measuring whether a judge was a freshman on the court is significant in both countries and in the expected direction: freshman judges are less likely to be placed on panels (Canada, p<0.001; South Africa, p<0.05). Thus, even in Canada, it appears that chief justices do manage to shield at least first-year judges from some of the heavy workload.

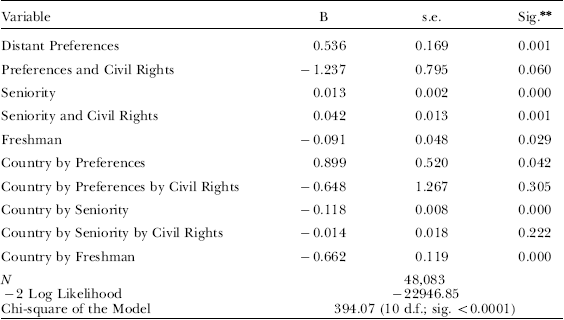

We also demonstrate these effects in a single model analyzing both countries by using interaction variables that control for the differences across systems. Our argument asserts that comparative analyses are possible across diverse social systems. Therefore, analyses must be able to assess methodologically the different effects of variables within each system as well as the effects generally across all systems. Thus we prefer to also present these results in Table 2. We coded the interaction variables included in our model with Canada as (1) and South Africa as (0). The coefficients of these variables will be significant when the statistics for core variables are significantly different across the countries and will not be significant when there are no differences.

Table 2. Conditional Logit Analysis of the Hypothesized Determinants of Panel Assignments in the South African and Canadian Supreme Courts with Interactions for Country

** Level of statistical significance. Based on one-tailed tests for variables in the expected direction.

Due to the way we coded the interaction terms, the first five variables in Table 2 replicate the results for the separate South Africa model. However, the interaction terms are of interest. The country-control interaction for distant preferences suggests that there are significant differences between the countries, but they are both positively related. The interaction assesses the magnitude. That is, chief justices in Canada are significantly more likely to assign judges with distant policy preferences to panels than are those in South Africa, but both do so. Perhaps the smaller court size and larger panel sizes in Canada leave these chief justices with less opportunity to assign like-minded judges on a regular basis. However, the interaction of the effect of distant preferences and the presence of a salient civil rights or liberties issue is not significant. Chief justices in both countries are more likely to assign judges with close policy preferences to cases involving more interesting issues. This finding suggests that judicial behavior may be similar across borders when opportunity allows. Chief justices in very different legal systems appear to use the power of panel assignment presumably to influence outcomes in particular cases.

As expected from the individual country results, the country-control interaction for seniority also indicates that there are significant differences between the two countries. Canadian chief justices are significantly more likely to appoint junior judges than are those in South Africa. As previously discussed, the larger panel sizes in Canada may result in workload pressures that force the Canadian chief justice to utilize his junior judges more often. However, the seniority and civil rights issues interaction is not significant. This finding indicates that in both countries, while junior judges generally are more likely to be assigned to cases, they are not more likely to be assigned to salient cases. Finally, the country-control interaction for the freshman variable indicates that while both countries assign freshman judges less frequently to panels, Canadian chief justices do so significantly less than their South African counterparts. Given the results for the seniority variable, it appears that a judge's first year on the bench in Canada is regarded very differently than are subsequent years.

Our results suggest that individual chief justices are similarly motivated when considering the use of their power to assign like-minded judges to panels. Despite the dramatic political, social, and economic differences between the two systems, similarities in behavior are evident. However, the results also suggest that chief justices may behave differently across the two systems. While Canadian chief justices are more likely to assign junior colleagues to cases as a whole, South African chief justices prefer to assign their senior colleagues to cases. In addition, the country interaction results suggest that Canadian chief justices may face different constraints than their South African colleagues. They are even more likely to appoint those further from them ideologically to panels in cases as a whole. The differences that do exist between the courts in each country may be having an impact. The larger panel size in Canada may limit the Canadian chief justices' opportunity to leave certain members off a panel, thus limiting their chance to disproportionately appoint like-minded judges. Instead, the Canadian chief justices may actually have to reserve those with whom they agree for the most salient cases. Conversely, the South African chief justices have a larger pool of judges from which to draw and smaller panels on which to place them. This logistically provides greater opportunity to manipulate panel composition in South Africa. Nonetheless, the results suggest that neither Canadian nor South African chief justices randomly assign judges.

Discussion and Conclusions

We believe that comparative research should encompass multiple-country studies evaluating individual behavior. Such studies will allow scholars to build general theories for certain hypothesized relationships in judicial research. We assert that countries, even those as diverse as Canada and South Africa, can be compared. Judging is a political behavior that exhibits similar actions affected by similar influences. These results suggest that panel assignment is one such behavior.

Of course, individual country studies remain essential. It is possible that system-specific factors influence the results. For example, a model developed strictly for Canada might include a variable for whether the judge is female. Chief justices may appoint female judges to panels more often in order to ensure diversity on the bench. Such a variable is inappropriate for South Africa, where no female judge served during the period examined. In addition, the civil law tradition in Quebec has led to the requirement that three Supreme Court judges be from that province at any given time. The rationale behind that requirement suggests that the chief justice will necessarily be sensitive to the need to have the three Quebec judges hear civil law cases coming out of that province. For South Africa, cases involving apartheid were presumed to be particularly important politically. Chief justices may have been careful to appoint like-minded judges for these panels, and even more likely to appoint themselves. In addition, the changes in the South African Court over the years suggest that different chief justices may have been more purposive in panel assignments.Footnote 28 While individual country studies could and should develop more complex and fully specified models that account for country-specific variables, we do not attempt these models here. We are merely testing whether the major theoretically relevant hypotheses can be transported across borders.

Examining chief justices' decisions across countries provides one avenue for examining behavior among judicial actors. Using comparable measures of dependent and independent variables, we find that chief justices in both Canada and South Africa do not assign their colleagues randomly. In both countries, policy preferences have an impact on those decisions. Chief justices appoint those further from their preferences for cases as a whole, with Canadian chief justices more likely than South African chief justices to assign those further from them to panels. However, when panels concern salient issues, both Canadian and South African chief justices appoint judges closer to them more often. In addition, seniority has an impact in both countries, albeit in a different direction for each.

Future research must attempt to delineate the relationships we assessed even more precisely. Because we measured preferences as the absolute value of the distance from the chief justice, extremely conservative judges and extremely liberal judges will have the same score. The Canadian chief justices have larger panel sizes and may appoint both extremely conservative and extremely liberal judges to the panels alongside members who are more closely aligned with the chief justice. The ideologues will then be marginalized, and the panel median will remain closer to the chief justice. Such ideologues may be less common in South Africa, giving the chief justice a simpler decisionmaking calculus in panel choices.

Future research should also expand our simplistic model to include other potential influences such as issue specialization or other indicators of case importance. Finally, future research should evaluate the effect of chief justices' panel assignments on outcomes. It may be that the chief justices are attempting to wield greater influence over court decisions but futilely so. Conversely, chief justices' behavior may be significant in terms of policy outcomes of high courts.

Beginning with a simple plan to test the feasibility of cross-country studies exploring judicial behavior, we selected a common behavior, panel assignment, across very diverse countries. Our analysis suggests that some aspects of existing judicial theory can be used to explain behaviors beyond the borders of the United States. The addition of other countries is obviously necessary to increase our confidence in that assertion, but this research demonstrates the feasibility of analyses across widely differing social systems, an important finding for the future of comparative research.