Why do some federal circuit court precedents transmit across circuits when others do not? Does judicial opinion language influence which cases are more likely to transmit? Previous research on the transmission of precedents has focused primarily on attributes of the circuits or judges who wrote the decisions (Reference LandesLandes et al. 1998; Reference KleinKlein 2002), without considering whether opinion language also influences citations. Can judges on the U.S. Courts of Appeals use the language of their opinions to persuade judges in other circuits that a precedent is important and worth citing?

Understanding why precedents transmit is important because it reveals whether judges have the potential to influence the behavior of peer judges on coequal courts. Because judges on the U.S. Courts of Appeals generally do not have authority to decide cases that originate in other circuits, opinion writers can extend their influence by encouraging judges in other circuits to cite them. A favorable citation does not guarantee that a judge will have a meaningful impact on another circuit's policies, but it does provide the opinion writer with an opportunity for influence by incorporating a precedent into the law of a circuit and giving the opinion writer authority over cases and controversies that would be otherwise out of reach.

Citations can also expand the impact of judges by broadcasting their decisions to other judges, litigants, and legal commentators who are sympathetic to their policy choices and are willing to act on them. Litigants in other circuits might develop new strategies based on the theories advanced in precedents, or legal commentators might comment favorably on precedents in law review articles. In this way citations function as a form of advertising for the original opinion writers, allowing judicial policies to circulate until they find the most receptive audiences.

Of special interest is the possibility that judges can encourage citations using just the language of their opinions. Research on the impact of courts has often claimed that judges are constrained policy makers with limited resources to influence the behavior of individuals who do not already support their decisions. As Rosenberg put it, “court decisions are neither necessary nor sufficient for producing necessary social reform” (1991:35). A constrained view of courts would maintain that opinion language is unlikely to influence other actors because it does not create sufficient incentives for these actors to listen to what judges have to say (but see Reference FeeleyFeeley 1992; Reference McCannMcCann 1992; Reference Schultz, Gottleib and SchultzSchultz & Gottleib 1998; Reference Canon and JohnsonCanon & Johnson 1999).

Other scholars have been more optimistic about the impact of courts and have viewed opinion language as a potential source of strength for judges. For example, Reference MurphyMurphy believed a judge's ability “to reason with taut logic” and “to use persuasive rhetoric” would “increase the professional esteem in which judges hold him and in turn would make them more ready to accept his arguments” (1964:98). Supporters of the strategic model of judicial behavior have elaborated on Murphy's work, showing how federal judges try to advance their goals using opinion language such as the legal grounding (Reference Smith and TillerSmith & Tiller 2002; Reference KingKing 2007), the supporting evidence (Reference CorleyCorley et al. 2005; Reference HumeHume 2006), and other instruments (Reference Spiller and SpitzerSpiller & Spitzer 1992).

However, it is unclear whether these forms of opinion language actually influence the behavior of actors who are responsible for interpreting and implementing court decisions. One might expect judges to have particular difficulty using opinion language to influence the behavior of judges on coequal courts. Because judges on the U.S. Courts of Appeals do not have supervisory authority over judges in other circuits, they cannot rely on the contempt citations, reprimands, and other forms of coercion they use to influence subordinates such as district court judges and federal administrators. Opinion writers also cannot count on persuading other judges that their decisions are correct on the merits because the judges they are addressing are experts in the field with well-formed attitudes about the legal questions at issue.

If opinion language does influence the transmission of precedents, it is most likely by persuading judges in other circuits that precedents are important and worth citing. Norms of stare decisis encourage judges to cite precedents to enhance the legitimacy of their decisions. Reference Epstein and KnightEpstein and Knight observed that if judges “want to establish a legal rule of behavior that will govern the future activity of the members of the society in which their court exists, they will be constrained to choose from among the set of rules that the members of society will recognize and accept” (1998:164). Norms of stare decisis may not apply with the same force to intercircuit citations as they do to citations from within the circuit, but judges who cite important precedents from other circuits can reinforce the legitimacy of their judgments by showing that their arguments are widely supported. Opinion writers who emphasize the importance of their decisions may therefore be able to encourage judges in other circuits to cite them.

To assess the impact of judicial opinion language on citation patterns, this study examines the transmission of precedents among judges on the U.S. Courts of Appeals, based on a sample of administrative cases from the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA), the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). The analysis controls for ideology, self-citations, and signals of case importance that opinion writers do not control, such as the nature of the legal question and the presence of a dissent. However, the primary hypothesis is that precedents are more likely to transmit to other circuits when opinion writers communicate the importance of their decisions using opinion language such as the legal grounding, the amount of supporting evidence, and the decision to file a per curiam opinion.

Previous Research on the Transmission of Precedents

Previous research on the transmission of precedents has not explicitly considered the influence of opinion language, but it does suggest that judges do not merely cite precedents based on whether they agree with the results. Judges look for important precedents, as communicated by the reputation of the opinion writer (Reference Canon and BaumCanon & Baum 1981; Reference CaldeiraCaldeira 1985; Reference LandesLandes et al. 1998; Reference KleinKlein 2002). Studies of the diffusion of innovations among state supreme courts have found that citations vary based on attributes of the judges who developed the new rules, including their professionalism, party affiliations, and education levels (Reference Canon and BaumCanon & Baum 1981; Reference CaldeiraCaldeira 1985).

Research on the U.S. Courts of Appeals has reinforced these findings, affirming that attributes of judges can explain which precedents transmit to other circuits (Reference KleinKlein 2002; Reference LandesLandes et al. 1998). Reference KleinKlein (2002) found that the prestige of judges, their expertise, and the support of multiple circuits affect which new legal rules other circuits are likely to adopt. Although he acknowledged that policy preferences also affect diffusion patterns, Klein concluded that the influence of prestige and expertise suggests that ideology by itself is insufficient to explain diffusion patterns. Judges “would have no reason to assume that experienced or highly regarded judges were more likely to share their ideological leanings or would otherwise have a greater tendency to choose policies compatible with their own preferences” (Reference KleinKlein 2002:138).

One might assume that judges only pay attention to the prestige and professionalism of opinion writers when citing precedents that announce new legal rules. Unlike routine precedents, decisions announcing new rules are often “major departures” from established doctrine and have uncertain policy implications (Reference Canon and BaumCanon & Baum 1981:976), which means that judges are likely to have special incentives to evaluate them in light of the credentials of their authors. However, Reference LandesLandes and colleagues (1998) investigated the citation of routine precedents by judges on the U.S. Courts of Appeals and found that characteristics of the circuits and judges who authored them also help determine how these cases transmit. Self-citation, circuit specialization, and graduation from a prestigious law school all help determine whether other judges cite an opinion writer's decisions.

The theme that emerges from the literature on the diffusion of precedents is that case features other than ideology influence the transmission of legal citations and that these features affect the diffusion of both policy innovations and routine precedents. Judges respond to the credentials of opinion writers, including their prestige and expertise. They make judgments about the quality of different circuits, and these considerations help judges determine which precedents to cite. It seems reasonable, then, to expect judges also to evaluate judicial opinion language. Just as the prestige and expertise of opinion writers can help judges evaluate cases, opinion language provides information that can help judges decide which cases to cite.

The Importance of Opinion Language

What information does opinion language communicate? One possibility is that it persuades readers on the merits, that the outcome a court has chosen is the correct one and should therefore be followed. But this effect seems unlikely, especially in light of a substantial literature showing that policy preferences determine how judges on the U.S. Courts of Appeals decide cases (Reference GoldmanGoldman 1966, Reference Goldman1975; Reference Songer, Gates and JohnsonSonger 1991; Reference Songer and HaireSonger & Haire 1992; Reference HettingerHettinger et al. 2004). Since judges are likely to have already developed attitudes about the legal issues that arise in precedents, it seems unlikely that opinion writers have this sort of persuasive effect.

A second, more likely possibility is that opinion language signals that cases are important and worth citing. Judges on the U.S. Courts of Appeals generally are not required to cite precedents from other circuits, but it is in their interests to cite precedents that enhance the legitimacy of their decisions. When judges fail to cite important precedents from other circuits, they risk criticism from members of the legal community for failing to consult the work of potentially relevant authorities. Judges might reason that other actors will be less likely to accept the authority of their judgments unless they show that they have researched the legal questions by citing important precedents on the subject from other circuits.

At a more general level, judges on the U.S. Courts of Appeals should be more likely to cite important precedents if they care about how their precedents will be received. As Canon and Johnson observed in their study of judicial impact, judges care about how other actors respond to them: “Like the rest of us, judges want to maintain respect and avoid undue criticism, especially among peers” (1999:52). In recent work Baum has expanded on these themes, explaining, “Judges seek the approval of other people, and their interest in approval affects their choices on the bench” (Reference BaumBaum 2006:158). If judges care about obtaining the approval of their audiences, then they may try to associate their judgments with important precedents from other circuits.

One feature of majority opinions that can signal its importance is the choice of legal grounding, such as whether the principal basis of the court's decision is procedural or substantive. An opinion writer who bases a decision on the substantive interpretation of a statute or the federal Constitution will probably be cited before a judge who emphasizes procedural matters because cases with substantive groundings are more likely to appear important to other judges. Because the issues raised in procedural cases are routine and the available precedents are numerous, it is less likely that procedural cases will stand out.

In administrative cases, the distinction between procedural and substantive groundings is codified in the Administrative Procedure Act (1946). Section 706(2)(A) of the APA states that federal judges may “hold unlawful and set aside agency action, findings, and conclusions” that are “arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion or otherwise not in accordance with law,” and Section 706(2)(E) targets policies that are “unsupported by substantial evidence.” These provisions are commonly invoked when judges are not satisfied with the justifications agencies have provided for their policy choices. While not unimportant, procedural cases generally do not break new legal ground that would make judges in other circuits notice them. Precedents are more likely to attract attention when opinion writers raise substantive objections to agency policies, ruling against administrators for misinterpreting federal statutes or the Constitution.

It is true that litigants typically determine the legal questions before a court, and the arguments they raise can influence the legal grounding an opinion writer selects, but this analysis assumes that opinion writers have ultimate control over the choice of grounding. Previous research on the U.S. Courts of Appeals affirms that majority opinion writers manipulate the legal grounding for strategic purposes. Reference Smith and TillerSmith and Tiller (2002) demonstrated that judges strategically select the legal grounding in administrative cases to avoid review by the U.S. Supreme Court. Opinion writers choose reasoning process review when they favor the results chosen by theirpanels in order to deflect the attention of the justices but use statutory groundings when they dislike the results in order to encourage a certiorari petition and the possibility of reversal. If judges on the U.S. Courts of Appeals manipulate the legal grounding to avoid review by the Supreme Court, they may also use it to affect whether judges in other circuits notice and cite them. Litigants in administrative cases routinely raise a number of procedural and substantive challenges to agency policies, and it is up to opinion writers to determine what to emphasize.

Another feature of judicial opinion language that can influence citation patterns is the amount of supporting evidence used by majority opinion writers to justify case outcomes. A precedent that is backed with references to cases, statutes, and other materials is likely to appear more important than a precedent that is less well defended. Large quantities of supporting evidence signal to other judges that the outcome endorsed by a court is well grounded in legal authorities. It also suggests that the opinion writer has put a good deal of time and care into the decision and will probably reach the same conclusion in future cases. Either consideration is likely to make judges in other circuits feel that well-defended precedents are important and should be consulted when the same fact patterns arise in their own circuits.

Some might object that judges do not always read opinions carefully enough for supporting evidence to have this sort of impact on their behavior. But even judges who do not pay close attention to particular citations are likely to make general assessments about whether decisions are well supported. When precedents contain large quantities of supporting evidence, they leave the impression that their conclusions are better defended on the whole, making them seem more important than precedents that are less well defended. When judges are deciding which precedents to cite, the well supported decisions are likely to stand out from the rest because the opinion writers have taken the time to back their judgments with evidence.

For judges who do read opinions closely or who care about particular types of evidence, it is possible for an author's choice of citations to have more specific influences on their behavior. Research on political persuasion and priming indicates that recipients who trust certain sources are more likely to be persuaded by messages that are associated with these sources, even when the recipients are highly knowledgeable about politics (Reference Eagley and ChaikenEagley & Chaiken 1993; Reference Huddy and GunnthorsdottirHuddy & Gunnthorsdottir 2000; Reference Miller and KrosnickMiller & Krosnick 2000, Reference Miller and Krosnick2004; Reference Nelson and GarstNelson & Garst 2005). Judges who think positively about certain sources may transfer these attitudes about the sources to the opinions that cite them, making them appear more important and worth citing.

A third feature of judicial opinion language that can affect citation patterns is whether the majority opinion is signed. It is true that per curiam, or unsigned, opinions are sometimes used in important cases to express the institutional view of a court or to summarize the points of consensus among a fractured court, as in Buckley v. Valeo (1976) and New York Times v. United States (1971). But on the U.S. Courts of Appeals per curiam opinions are used most commonly in unimportant cases, such as summary judgments and unpublished decisions (Reference BashmanBashman 2007; Reference JacobsonJacobson 2005; Reference NygaardNygaard 1994). Judge Richard L. Nygaard of the Third Circuit expressed this sentiment when explaining how his colleagues view per curiam opinions:

The most famous opinion-writer in the history of American courts, “Per Curiam,” has gotten a bad rap. Per Curiam has been accused of writing the opinions for the court, when out of cowardice others do not wish to. Per Curiam has been accused of writing less-than-thorough explanations in simple affirmances. Per Curiam has been accused of being the handmaiden of law clerks. Indeed, Henry Manley recalls one New York judge's observation that “a per curiam opinion is one where we agree to pool our weaknesses.” (1994:50)

Judge Nygaard's comments raise the possibility that per curiam opinions transmit differently from other precedents. Refusing to sign an opinion may signal to judges in other circuits that a decision is unimportant and not worth consulting. Opinion writers who want to deflect attention from their judgments may be able to do so by presenting them as per curiam opinions, associating them with summary judgments, unpublished opinions, and other decisions that are generally regarded as less important.Footnote 1 It is therefore expected that per curiam opinions will result in fewer citations by judges in other circuits than signed opinions.

Research Design

To assess whether judicial opinion language influences the transmission of precedents, this study examines the citation of administrative cases by judges on the U.S. Courts of Appeals between 1982 and 2000.Footnote 2 Results are based on a sample of 357 cases reversing, vacating, or remanding the actions of three agencies, the BIA, the FCC, and FERC.

To draw the sample of cases for analysis, a list of all cases decided by the U.S. Courts of Appeals between 1982 and 2000 that reversed, vacated, or remanded final actions of the BIA, FCC, and FERC was compiled using Lexis. A random sample of cases was then taken from this list, with decisions screened for appropriateness before inclusion in the final database. It was desirable to use cases from several federal agencies so that the results of the study would not be confined to a single policy area, but it was also necessary to keep the number of agencies small in order to control for the number of legal issues involved.

Administrative cases are good candidates for citation analysis because they present legal questions that are likely to be of interest to judges in other circuits. Precedents cannot transmit when the same legal questions never arise again, but the standards judges use to review administrative cases are relatively uniform and clearly delineated in the APA. Judges are frequently investigating whether agencies have followed appropriate procedures, whether their actions have been adequately supported by the administrative record, and whether administrators have interpreted their controlling statutes correctly, among other considerations. The facts may vary from case to case, but the consistency of the standards means that administrative cases often relate to disputes arising in other circuits.

Administrative cases were also chosen because previous studies of judicial opinion language have also used cases involving administrative law (Reference Spiller and SpitzerSpiller & Spitzer 1992; Reference Tiller and SpillerTiller & Spiller 1997, Reference Tiller and Spiller1999; Reference Smith and TillerSmith & Tiller 2002). These studies demonstrated that judges manipulate opinion language in administrative cases to influence the behavior of other actors (Reference Tiller and SpillerTiller & Spiller 1999; Reference Smith and TillerSmith & Tiller 2002), which means that one can be more confident that the impact of opinion language is attributable to the opinion writers themselves. For example, Reference Smith and TillerSmith and Tiller (2002) used a sample of environmental cases to show that judges on the U.S. Courts of Appeals select legal groundings strategically to avoid review by the Supreme Court.

A potential drawback of using administrative cases is that they often track in particular circuits, which can make it more difficult for precedents to transmit than in other areas of law. While each of the agencies chosen for this study litigates in every circuit, certain circuits do tend to be more heavily represented in the sample than others. A majority of cases involving the BIA, for example, originated in the Ninth Circuit, while most of the cases featuring the FCC and FERC came from the D.C. Circuit. Because the distribution of the sample is uneven, one cannot automatically apply the conclusions of the study to other areas of law.Footnote 3

However, the use of administrative cases should not cast doubt on the validity of the central findings. If anything, one might expect the effects of the explanatory variables to be stronger in other areas of law. Because there are fewer opportunities for citations to transmit in administrative cases, it is probably more difficult for the explanatory variables to affect the citation of precedents in administrative cases than in other areas of law in which the distribution of cases is more uniform. By making it harder for the explanatory variables to attain statistical significance, administrative cases provide a more rigorous test of the research hypotheses.

It should also be remembered that while the distribution of cases is uneven, none of the agencies used in the study litigates exclusively in a single circuit, and precedents involving these agencies regularly spread to other jurisdictions. Although a majority of cases involving the FCC and FERC are decided by the D.C. Circuit, judges from the D.C. Circuit often consult the work of other circuits before issuing decisions, and their decisions are routinely cited by judges outside the District. In the same way immigration cases are regularly distributed among the circuits, even though a majority of BIA cases come from the Ninth Circuit.Footnote 4

To illustrate, Table 1 shows the frequency with which administrative cases in the sample have been cited by judges in other circuits. The results affirm that intercircuit citations occur but that the overall rate of citation is low. Nearly half of the cases in the sample (47.1 percent) were cited by other circuits, with 21.0 percent of cases cited once and another 13.1 percent cited twice. A small proportion of cases (1.6 percent) were cited 10 times or more, but no case was cited more than 13 times. While half of the cases in the sample (52.9 percent) were never cited by other circuits, there is enough variation in the dependent variable to permit a meaningful analysis.

Table 1. Summary of Dependent Variable Measuring the Total Number of Positive Citations to Federal Administrative Cases by Judges in Other Circuits (1982–2000)

Median=0.00, Mean=1.18, Std. Dev.=2.06, Min=0.00, Max=13.00.

The study focuses only on cases that reverse, vacate, and remand the actions of federal agencies because one can be more confident that the choice of legal grounding in these circumstances reflects the preferences of judges and not the litigants. When judges issue affirmances, they necessarily reject all the substantive and procedural objections raised by claimants, which makes it more difficult to know whether courts have chosen the legal groundings for their opinions. On the other hand, judges who overturn administrative policies select from among the objections raised by litigants and ground their opinions on the rationales they prefer to emphasize. One can more accurately say that one is studying the effects of an opinion writer's choice of grounding if one focuses just on cases overturning agency policies.

The analysis does not include unpublished opinions because they have no precedential value and cannot be expected to transmit to other circuits. For similar reasons, cases were also excluded if they were overturned or preempted by a decision of the Supreme Court, a panel rehearing, or a rehearing en banc. When cases are superseded by subsequent litigation, they are no longer available to cite, making them inappropriate for study. Each case in the sample represents the final legal judgment for the litigants and facts involved.

The dependent variable is a count of the number of cases in other circuits that cited each precedent approvingly after six years, using Shepard's Citations to collect the data. For example, if a case was decided in 1982, a count was made of the number of cases citing that precedent between 1982 and 1987. Like other studies of circuit behavior (Reference LandesLandes et al. 1998; Reference Klein and MorrisroeKlein & Morrisroe 1999), this study counted only intercircuit citations. Intercircuit citations were preferred to intracircuit citations because self-citations by a circuit are more likely to be influenced by norms of stare decisis (Reference LandesLandes et al. 1998); judges generally have no obligation to cite cases from other circuits. Positive citations were also preferred to negative ones because they are better indicators that judges have accepted precedents as important.Footnote 5

Measurement

Testing the effects of judicial opinion language on the transmission of federal circuit court precedents required developing measures of the principal legal grounding, the amount of supporting evidence used to justify the result, and the decision to file a per curiam opinion. To measure the grounding, a dummy variable was included in the analysis for whether the basis of the court's decision was procedural. Since the cases in the sample all involve administrative law, these classifications were made by determining which provision of Section 706(2) of the APA formed the basis of the court's analysis. The APA authorizes federal courts to overturn administrative actions when agencies commit certain procedural or substantive errors, as specified in the Act.Footnote 6 Cases were coded 1 when the principal legal grounding of the decision was a procedural section of the APA and 0 when the grounding was substantive. It was expected that the procedural basis variable would be negatively correlated with the dependent variable because judges should be less likely to cite procedural cases.

Measuring the amount of supporting evidence involved counting the number of block quotations in the majority opinion. Reference WalshWalsh (1997) suggested that block quotations are appropriate proxies for measuring how well defended opinions are because opinion writers use them with greater care than “weak” or “string” citations. For example, Walsh demonstrated that state supreme court judges are more likely to include block quotes when they are concerned about the legitimacy of case outcomes, such as when they are developing new legal rules: “Recognizing a new doctrine engenders particular concern with acceptability, and the judges in these cases clearly felt obliged to cite more often and widely” (1997:351).

To measure the block quotations variable, a count was made of the number of block quotations in the majority opinion. Quotations were included if they were at least three lines in length and referred to one of the following types of sources: (1) statutes, or laws of Congress and the states; (2) cases, or controlling decisions by state or federal courts; (3) agency rules, or the agency's own rules and procedures; (4) the record, or the evidentiary record compiled by the agency to justify its policies; (5) legislative history, or legislative commentary on statutes; and a (6) miscellaneous category for references to other materials such as law reviews. Results were combined into a single count of the number of block quotations in each opinion.

The scores were then divided by the total number of pages in the majority opinion. Because the quantity of block quotations is likely to be correlated with how long the opinion is, it was necessary to take the number of pages into account to ensure that block quotations were not just serving as a proxy for opinion length. The block quotations variable was therefore really a measure of the quotation density, based on the average number of block quotations per page of the majority opinion. It was expected that as the density of quotations in the majority opinion increased, the number of citations by judges from other circuits would also increase.

It must be emphasized that the purpose of including the block quotations variable was not to test whether judges were responsive to individual block quotations per se, but to determine whether well-supported opinions were more likely to be cited by judges in other circuits. Opinions with a large number of block quotations are probably also defended in other ways that are not as easily quantifiable. The number of block quotations in a majority opinion might be an imperfect measure of how well supported an opinion is, but it is objective, easy to reproduce, and a more valid measure than a simple count of the number of string citations.

Finally, a dummy variable was added to the analysis measuring whether a case was designated per curiam. The measurement for this variable was straightforward because unsigned majority opinions are clearly labeled as such in the heading. Cases were coded 1 when a case featured an unsigned per curiam opinion and 0 when it did not. It was hypothesized that the per curiam variable would be negatively associated with the dependent variable because per curiam opinions are less likely to be viewed as less important by other judges than signed opinions.

In addition to the key explanatory variables, the analysis controlled for the effects of several other potential influences on the transmission of federal circuit court precedents. The most important of these control variables measured the effects of ideology. Given the breadth of literature indicating that ideology influences the behavior of judges on the U.S. Courts of Appeals (Reference GoldmanGoldman 1966, Reference Goldman1975; Reference HettingerHettinger et al. 2004), it is reasonable to expect policy preferences to affect which precedents catch on. Decisions should be less likely to transmit when they are ideological outliers or are out of step with the attitudes of other judges. A variable was therefore developed measuring the ideological distance between the majority opinion writer's policy preferences and the average circuit ideology in the six years after a case was decided. Judicial ideology scores were based on the measures developed by Reference GilesGiles and colleagues (2001) from the Reference PoolePoole (1998) Common Space scores.Footnote 7 The ideological distance variable was calculated by taking the absolute value of the difference between the opinion writer ideology and circuit ideology scores.Footnote 8 Because judges are unlikely to cite cases that were written by ideologically distant judges, it was expected that the ideological distance variable would be negatively associated with the dependent variable.

The remaining variables measured signals of case importance that majority opinion writers do not control. These measures were necessary to show that the effects of judicial opinion language are not themselves a reflection of the underlying importance of the issues or facts in a precedent.Footnote 9 If the choices judges make in their majority opinions are substantively meaningful, opinion language should have an independent influence on whether judges in other circuits cite them, a relationship that holds up after taking other potential measures of case importance into account.

For example, one potential signal of case importance is whether a precedent has been previously cited by other judges within the same circuit. Reference LandesLandes et al. (1998) found that when circuit judges cite themselves, their opinions are more likely to be cited by judges in other regions, leading the authors to conclude that “advertising” and “self-promotion” affects the amount of attention a precedent receives (1998:323). One should therefore expect intracircuit citations to increase the number of citations by judges in other circuits. To measure the influence of self-citations, a variable was added to the analysis counting the number of within-circuit citations to a precedent that occurred in the six years after it was decided.

Another measure of case importance is whether a decision was published in U.S. Law Week, which reports major cases, regulations, and legislation, and is available on Lexis back to 1982. The publication of a decision in U.S. Law Week indicates that experts in the legal community considered a precedent to be important when it was handed down, so it is reasonable to think that judges in other circuits would also consider the decision to be as important.Footnote 10 For this reason, a dummy variable was included measuring whether a decision was published in U.S. Law Week, with the expectation that it would be positively associated with citations.

It is also possible that the importance of a case is signaled by the behavior of other judges on the panel. When a case is decided unanimously or by an entire circuit en banc, judges in other circuits are likely to think that the precedent is important and merits citation. On the other hand, when the panel awards an agency a partial victory, ruling in its favor on some but not all of the legal questions, the action mutes the case's importance as precedent by obscuring the message it communicates. To test these effects, dummy variables were developed measuring whether a case was unanimous, decided en banc, or handed the agency a partial victory.

Finally, the analysis controlled for the nature of the legal issue. If cases overturn agency rules, they are more likely to appear important to other judges than cases overturning adjudications, regardless of the signals that majority opinion writers wish to send. Adjudications apply to only a handful of litigants, but rule changes typically involve broad classes of citizens, and the wider policy implications automatically help these types of decisions stand out. Similarly, if a case raises a constitutional issue, it is likely to attract the attention of other judges regardless of whether the opinion writer makes the issue the center of the analysis. To control for these effects, two more dummy variables were added measuring whether the case involved a rule change and whether litigants raised a constitutional issue.

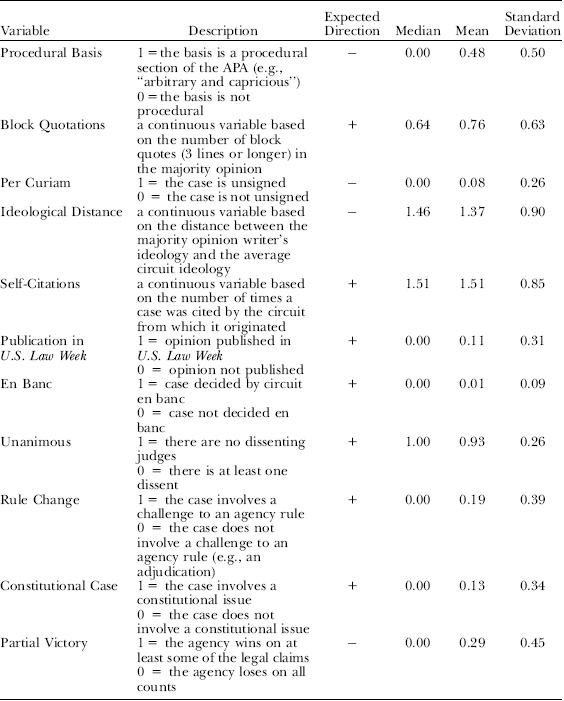

The coding criteria for the explanatory variables are summarized in Table 2. Dummy variables were included for each of the three agencies used in the study, with the BIA as the baseline. The model also controls for the year of the circuit's decision and adjusts for within-circuit correlation because citations may vary with time or with the circuit. Controls for individual circuits are especially important in light of evidence from previous research on the transmission of precedents that citation patterns reflect attributes of the circuits that authored the precedents (Reference Canon and BaumCanon & Baum 1981; Reference CaldeiraCaldeira 1985; Reference LandesLandes et al. 1998; Reference KleinKlein 2002).Footnote 11

Table 2. Summary of Independent Variables Used to Model Positive Citations to Federal Administrative Cases by Judges in Other Circuits (1982–2000)

N=357.

Results

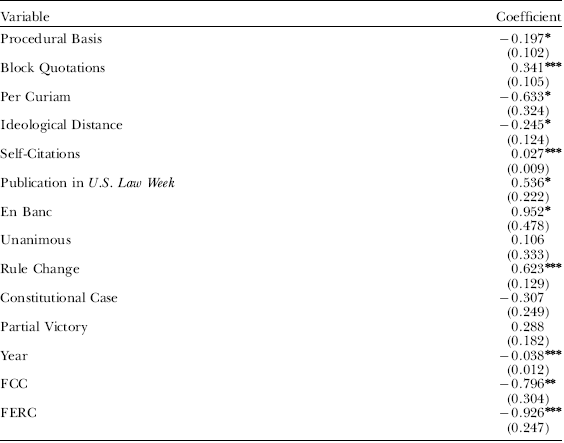

Table 3 presents the results of a negative binomial regression model predicting the number of positive citations to federal administrative cases by judges in other circuits. Coefficients are presented with robust standard errors reported in parentheses. The model is a good fit overall, with a Wald chi-square of 15,278.41 that is statistically significant at the p<0.001 level.

Table 3. Negative Binomial Regression Model Predicting Positive Citations to Federal Administrative Cases by Judges in Other Circuits (1982–2000)

N=357;

*** Wald chi2 (11)=15,278.41;

* p<0.05;

** p<0.01;

*** p<0.001.

As hypothesized, all three features of judicial opinions have an impact on the citation of precedents by judges in other circuits. The density of block quotations in a majority opinion is positively associated with the number of citations, while the use of a procedural grounding and the decision to leave an opinion unsigned are negatively associated with citations. Together these findings permit one to reject the null hypothesis that opinion language has no impact on citation patterns. Judges do make citation decisions based on the information that is communicated in majority opinions and are less likely to cite cases that appear unimportant.

A number of the control variables in Table 3 also perform as expected. Ideology has a statistically significant impact on citation patterns, affirming that judges are less likely to cite cases that depart from their policy preferences; and several of the measures of case importance also attain significance. Precedents are more likely to be cited when they have been cited by the circuits that authored them, when they have been published in U.S. Law Week, when they are issued by a panel convening en banc, and when they require an agency to change its rules. These results affirm that judges respond to indicators of case importance aside from those communicated by a majority opinion writer. The results also show that the effects of judicial opinions hold up when other independent measures of case importance are taken into account.

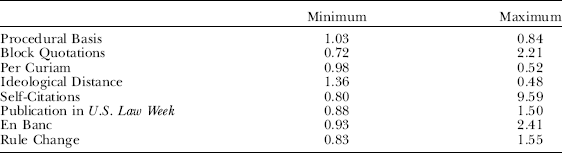

Because negative binomial regression coefficients do not lend themselves to straightforward substantive interpretation, Table 4 lists the number of intercircuit citations that are expected to occur when certain independent variables assume given values and other variables are set at their means. Table 4 reports that when a majority opinion writer chooses a procedural grounding, the expected number of citations decreases from about 1.03 citations to 0.84 citations; issuing a per curiam opinion decreases the number of citations from 0.98 to 0.52; and a high density of block quotations increases the number of citations from 0.72 to 2.21.

Table 4. Predicted Count of Positive Citations to Federal Administrative Cases by Judges in Other Circuits (1982–2000), at Given Values of Certain Independent Variables

N=357.

These effects are substantively quite small, but they still have the potential to be meaningful to opinion writers. As Table 1 reports, judges do not usually cite routine administrative cases from other circuits more than once or twice. The mean number of intercircuit citations in the sample is 1.18, while the median number of citations is 0. With the rate of citation so low, it is possible that an increase of one or two additional citations would make a difference to opinion writers, ensuring that a precedent is at least noticed by other circuits.

Table 5 reports the combined effects of the three main explanatory variables and affirms that features of judicial opinions net judges an increase of about two citations. When judges write unsigned opinions, use procedural groundings, and include no supporting evidence, the expected number of citations from other circuits is 0.36. But when judges sign their opinions, use substantive groundings, and the supporting evidence is at its maximum, the number of citations increases to 2.55. Once again the effects are small, but they at least affirm that opinion language affects the transmission of circuit court precedents. It should be remembered that the analysis tests only three features of judicial opinions, and all three have an influence on a precedent's tendency to be cited. It is possible that other features of judicial opinions also have an impact on citation patterns that would further increase the number of citations.

Table 5. Predicted Count of Positive Citations to Federal Administrative Cases by Judges in Other Circuits (1982–2000), Combined Effects of Certain Variables

N=357.

Of the remaining variables that were tested, Table 4 indicates that the variable with the strongest influence on citation patterns is self-citation by the circuit that authored the precedent. When the number of intracircuit citations increases from its minimum to its maximum values, the number of expected citations by other circuits rises from 0.80 to 9.59. Consistent with Reference LandesLandes and colleagues (1998), advertising and self promotion by the circuit that authored a decision has a strong impact on whether precedents catch on. The other control variables have smaller effects. Publication in U.S. Law Week is associated with an increase in the number of citations, from 0.88 to 1.55; decisions that are issued by a circuit en banc receive 2.41 citations, compared to 0.93 citations for decisions issued by traditional three-judge panels; and when a precedent involves a rule change, the number of citations increases from 0.83 to 1.55.

Finally, Table 4 shows that precedents written by judges who are ideologically distant from circuit preferences tend to be cited about half as frequently as precedents that are more ideologically compatible. When the ideological distance between an opinion writer and other circuits is at its maximum, the expected number of citations is 0.48, compared to 1.36 citations when the ideological distance is at its minimum. Precedents that stray ideologically from the preferences of other circuits are less likely to be adopted, independent of how important the precedents appear from the signals that are communicated in majority opinions.

Discussion

The results of the quantitative analysis indicate that judicial opinion language affects the transmission of federal circuit court precedents. Judges in other circuits pay attention to the content of opinions and cite important precedents, as communicated to them by the legal grounding, the supporting evidence, and the identification of an opinion as per curiam. The implication is that judges who would like to influence policy and are willing to take affirmative steps to encourage citations can use opinion language to enhance their impact.

The findings are significant for at least two reasons. First, they indicate that judges have the ability to influence the behavior of policy makers whom they have no formal authority to supervise, such as judges on coequal courts. Judges on the U.S. Courts of Appeals have no means of compelling judges in other circuits to cite them, but opinion language still manages to persuade judges that precedents are important and worth citing. Contrary to the predictions of the constrained court model (Reference RosenbergRosenberg 1991), judges can affect the behavior of other actors without resorting to sanctions and threats.

Second, the results affirm that opinion language is a resource that judges can use to attain their policy goals. Research on strategic behavior has found that judges try to influence the behavior of other actors using instruments such as the legal grounding (Reference Spiller and SpitzerSpiller & Spitzer 1992; Reference Tiller and SpillerTiller & Spiller 1997, Reference Tiller and Spiller1999; Reference Smith and TillerSmith & Tiller 2002; Reference KingKing 2007) and the supporting evidence (Reference CorleyCorley et al. 2005; Reference HumeHume 2006), but this literature has not demonstrated that these language strategies work. The findings here contribute to the strategic literature by providing empirical evidence that legal instruments can be effective, which suggests that it is rational for judges to use opinion language to expand their influence.

A limitation of the study is that, like previous studies on the impact of judicial opinion language (Reference Spiller and SpitzerSpiller & Spitzer 1992; Reference Tiller and SpillerTiller & Spiller 1997, Reference Tiller and Spiller1999; Reference Smith and TillerSmith & Tiller 2002), the sample only uses cases involving administrative law. Because administrative cases have low salience and do not transmit to other circuits as frequently as decisions in other fields, the capacity of judicial opinion language to influence the transmission of administrative precedents may be diminished. These tendencies of administrative cases must be taken into account before applying the results to other areas of law in which precedents transmit more freely.

Fortunately, the choice of administrative cases should not cast doubt on the validity of the central findings. Because administrative cases tend to track in particular circuits, it should be more difficult for the explanatory variables to attain statistical significance in administrative cases than in other areas of law in which the distribution of cases is more uniform. The fact that opinion language manages to affect the transmission of routine administrative cases anyway indicates that the results of the study could be even stronger in other areas.

Another limitation of the study is that the findings do not allow one to evaluate the substantive impact of citations on the policies and practices of other circuits. Because judges on the U.S. Courts of Appeals do not have authority over cases that arise in other circuits, opinion writers cannot develop and extend precedents on their own initiative, relying instead on other litigants and judges to continue the work. The impact of precedents may be limited if these actors are unresponsive or if the individuals who are responsible for implementing court decisions are unwilling or unable to act. One must therefore be careful not to overstate the amount of policy impact that an opinion writer can expect from a single citation.

A citation plants a seed but requires other actors in the circuit to nurture it. If the judges or litigants in the circuit ignore the citation or decide to limit its application, it is unlikely to enhance the impact of the original opinion writer. Other times, however, precedents do take root, and opinion writers who have obtained favorable citations are in a position to spread their influence. In this way opinion writers extend their authority beyond the original parties who filed suit to other parties in other suits in other jurisdictions.

Conclusion

The study set out to determine whether features of judicial opinion language influence the transmission of routine administrative precedents. It found that precedents are more likely to transmit when opinion writers signal the importance of their decisions with such features as the choice of legal grounding, the quantity of supporting evidence, and the decision to file a per curiam opinion. These results indicate that opinion writers have resources to facilitate the transmission of their decisions. Taking advantage of the tools most readily available to them, judges can use opinion language to influence the behavior of judges on coequal courts.

Future research can determine whether judges communicate other signals in their opinions and whether these signals have similar effects on other policy makers. If opinion language affects the behavior of judges in other circuits, then one might expect it also to affect actors whom judges actually have authority to supervise, such as district court judges and federal administrators. It is also worth examining whether judges can use opinion language to influence the behavior of their superiors on the Supreme Court. Such research may find that judges do more to encourage implementation than is often acknowledged.