Interest groups pursue their goals in a wide array of venues, including the courts. Indeed, solely within the realm of the U.S. Supreme Court, groups have numerous methods for participation, from setting up test cases to sponsoring cases that others bring to testifying at judicial confirmation hearings; some groups even hold vigils outside the marble pillars awaiting the Court's final decisions on cases touching on group interests. However, the most common method of interest group involvement in the Supreme Court is the amicus curiae brief (Reference Caldeira and WrightCaldeira & Wright 1988; Reference Epstein, Gates and JohnsonEpstein 1991). In fact, amicus briefs are filed in almost every case the Court accepts for review (Epstein & Knight 1999:221; Reference Kearney and MerrillKearney & Merrill 2000). Far from their literal translation, however, amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) briefs are not neutral sources of information. Instead, these briefs are advocates for the parties (Reference KrislovKrislov 1963). Amicus curiae briefs are most commonly submitted to the Court urging the justices to rule in favor of one litigant over another (Reference Kearney and MerrillKearney & Merrill 2000:841–2; Reference Spriggs and WahlbeckSpriggs & Wahlbeck 1997:371).

Past research on the impact of amicus briefs in the Supreme Court has indicated that the presence of amicus briefs increases the likelihood of a grant of certiorari (Reference Caldeira and WrightCaldeira & Wright 1988; Reference PerryPerry 1991) and influences litigant success on the merits (Reference Kearney and MerrillKearney & Merrill 2000; Reference McGuireMcGuire 1990, Reference McGuire1995; Reference PuroPuro 1971; compare with Reference Songer and SheehanSonger & Sheehan 1993).Footnote 1 However, virtually none of this research has explicitly examined why amicus briefs influence litigation success. “One of the shortcomings of previous … studies of amicus briefs is that they often fail to articulate a clear hypothesis about how information contained in amicus filings influences the decision making of the Supreme Court” (Reference Kearney and MerrillKearney & Merrill 2000:774).

In this study, I examine two theories regarding why amicus briefs might increase litigation success. The first, the affected groups hypothesis, holds that amicus briefs are efficacious because they signal to the Court that a wide variety of outsiders to the suit will be affected by the Court's decision.Footnote 2 Thus, regardless of the social scientific, legal, or political information that the briefs contain, this hypothesis asserts that it is simply the number of organizations present on a brief that should influence the Court's decision. The second, the information hypothesis, asserts that amicus briefs are effective, not because they signal how many affected groups will be impacted by the decision, but because they provide litigants with additional social scientific, legal, or political information supporting their arguments.

This article proceeds as follows. First, I offer a brief discussion of the rules and norms regarding amicus participation. Next, I discuss two sources of information that allow the justices to take full advantage of their policy preferences and create effective law. Following this, I discuss how the affected groups and information hypotheses differ and the observable behavior each would suggest. Here, I present testable hypotheses that will be useful for examining whether one or both of these theories help explain the influence of amicus participation. Next, I discuss the data and methodology utilized in this project, followed by the results from the multivariate analysis. The article ends with a discussion of interest group goals and motivations for both filing individual briefs and joining briefs prepared by other organizations, as well as implications of this analysis for the study of judicial decisionmaking.

A Brief Overview of the Rules and Norms Governing Amicus Curiae Participation

Though Supreme Court Rule 37 contains explicit guidelines regarding amicus curiae participation on the merits, in practice, the Court allows for essentially unlimited participation. Private amici, such as interest groups, must obtain permission from both of the parties to litigation to participate, which is often granted. If one or both of the parties refuse to grant such consent, the potential amici may petition the Court for leave to file, and the Court almost always grants such petitions (Reference Bradley and GardnerBradley & Gardner 1985; Reference O'Connor and EpsteinO'Connor & Epstein 1983).Footnote 3 Unlike private amici, representatives of federal and state governments are not required to obtain permission from the parties to file amicus briefs. On rare occasions, the Court may request the participation of an amicus, usually the Solicitor General or an administrative agency of the federal government; such invitations are almost always accepted (Reference SalokarSalokar 1992:143). In general, once permission to file an amicus brief is granted, the brief is filed and the amicus's involvement in the case ends.Footnote 4 Thus, unlike intervenors, who are bound by the resulting judgment, amici are not affected beyond the broader ramifications of the case (Reference CoveyCovey 1953:31). However, on rare occasions, amici may be given oral argument time by the Court, generally only with the consent of the parties. Similar to invitations to file, oral argument time typically involves the Solicitor General or an administrative agency of the federal government (Reference Stern, Gressman, Shapiro and GellerStern et al. 2002:684).

Sources of Outside Information in the Supreme Court

It is well established that, no matter how sophisticated the justices on the Supreme Court may be, they operate in an environment of incomplete information (Reference Epstein and KnightEpstein & Knight 1998; Reference Maltzman, Spriggs and WahlbeckMaltzman, Spriggs, Reference Murphy& Wahlbeck 2000:105; Murphy 1964). Often, this means the justices must seek out information in order to direct them to policies that will maximize their policy preferences and create what they believe to be efficacious law. Reference Epstein and KnightEpstein and Knight (1998, Reference Epstein, Knight, Clayton and Gillman1999) identify two such sources of information. The first source of this information is public opinion, communicated to the Court via the media. “Simply put, we have no reason to suspect that justices, just like other Americans, do not obtain information about current events from television, the radio, and newspapers. Indeed, all the available evidence suggests that justices do, as the saying goes, ‘follow the election returns’” (Reference Epstein, Knight, Clayton and GillmanEpstein & Knight 1999:220). Evidence of this claim comes from both anecdotal and more rigorous sources. A clear example of the former is Chief Justice Rehnquist's criticism, in dissent, of the majority's decision in Atkins v. Virginia (2002) for its reliance on public opinion polls to justify the decision. As to the latter, numerous studies exist showing that the Supreme Court reacts to changes in public opinion, although a debate over how the Court's responsiveness to public opinion manifests itself still continues (Reference CasperCasper 1976; Reference DahlDahl 1957; Reference Flemming and Dan WoodFlemming & Wood 1997; Reference FunstonFunston 1975; Reference MarshallMarshall 1989; Reference Mishler and SheehanMishler & Sheehan 1993, Reference Mishler and Sheehan1994; Reference Norpoth and SegalNorpoth & Segal 1994; Reference Stimson, MacKuen and EricksonStimson, MacKuen, & Erickson 1995).

A second source of information for the justices is the amicus curiae brief, submitted by outsiders to the case who believe the outcome will affect them. Unlike public opinion, amicus briefs allow the justices “to make potentially precise calculations [regarding the impact of a decision] because these briefs are geared toward the specific issues at hand” (Reference Epstein and KnightEpstein & Knight 1998:146). In so doing, amicus briefs provide the Court with information regarding the number of potentially affected parties, these parties' optimal dispositions, and social scientific, political, and legal arguments that often buttress those arguments submitted by the parties to litigation (Reference EnnisEnnis 1984; Reference PuroPuro 1971; Reference Rustad and KoenigRustad & Koenig 1993; Reference Spriggs and WahlbeckSpriggs & Wahlbeck 1997; Reference WasbyWasby 1995). Thus, contrary to public opinion, which may manifest itself as an influence on the Court years after it shifts, amicus briefs provide the justices with information regarding a particular case at hand. Accordingly, we would expect the influence of amicus participation to reveal itself on a case-by-case basis.Footnote 5

The Affected Groups and Information Hypotheses

While it is evident that the number of amicus briefs submitted to the Court has increased dramatically since the 1960s (Reference Epstein, Segal, Spaeth and WalkerEpstein et al. 1994; Reference KoshnerKoshner 1998; Reference O'Connor and EpsteinO'Connor & Epstein 1982), it is equally important to note that the number of participants on these briefs has also proliferated. That is, the Court has seen an increase in the raw number of briefs filed and also an increase in the number of cosigners on these briefs. In fact, as Figure 1 illustrates, by the mid-1970s the number of participants on briefs increased twice as fast as the number of briefs filed.Footnote 6 By 1980 this increase was even more significant, and by 1985, the number of participants on briefs was almost four times greater than the number of briefs filed.Footnote 7 Indeed, Figure 1 demonstrates that the Court has seen not only an interest group litigation explosion, indicated in the number of briefs filed, but also an interest group participation explosion, seen in the number of groups joining briefs.

Figure 1. Total Number of Amicus Curiae Briefs and Participants by Term, 1953–1985 Terms

The fact that the Court is seeing more and more amicus briefs joined by numerous groups lends itself to a consideration of what type of information this sort of coalitional politics supplies to the Court. While an individual brief, filed by a single amicus, is capable of supplying legal, political, and social scientific information to the Court (Reference EnnisEnnis 1984; Reference Epstein and KnightEpstein & Knight 1998:146; Reference PuroPuro 1971; Reference Rustad and KoenigRustad & Koenig 1993; Reference WasbyWasby 1995), a large number of organizations cosigning a single brief do not add to that information. Instead, having a large number of participants on a brief signals to the Court that a great number of groups, and by implication their members, will be impacted by the decision and these groups' preferences. In this sense, “Alliances provide means of showing broader support for a cause of interest” (Reference HojnackiHojnacki 1997:67).

Consider, for example, the amicus effort in Webster v. Reproductive Health Services (1989). In Webster, 78 amicus briefs were filed with the Court (31 for the respondents and 47 for the petitioners), representing a diverse collection of more than 400 different organizations (Reference KolbertKolbert 1989). Of these organizations, 335 filed on behalf of the respondents, while only 85 filed on behalf of the petitioners (Reference Behuniak-LongBehuniak-Long 1991). “Clearly, the [respondent's amici] acted as if the number of sponsors was more important than the number of briefs filed, while the [petitioner's amici] favored the strategy of filing the most briefs” (Reference Behuniak-LongBehuniak-Long 1991:262).Footnote 8 Thus, it appears that the respondent amici acted on the belief that the justices could be swayed by the sheer numbers associated with the abortion rights position; i.e., the belief that justices on the Supreme Court are susceptible to the democratic principle of majority rule. As such, although the amicus effort in Webster was unprecedented, and therefore may not be the most generalizable example, it nonetheless illustrates the notion that interest group amici may genuinely believe that the Court responds to the principles of democratic rule. At a minimum, it suggests the need to determine “which is a more effective strategy, to file as many individual briefs as possible or to gather a larger total number of cosponsoring organizations?” (Reference Behuniak-LongBehuniak-Long 1991:262).

From the perspective of the justices, a large number of cosigners supporting a particular litigant may serve as a crude barometer of public opinion on an issue (Reference Kearney and MerrillKearney & Merrill 2000). While traditional notions of how the Court renders decisions assert that the justices are immune from majoritarian pressures (e.g., Reference BickelBickel 1986), scholars since Reference DahlDahl (1957) have noted that this view may offer only an incomplete picture of the Court. In essence, two explanations exist for why the justices may be influenced by public opinion.

First, because the justices genuinely care about having their decisions overridden, altered, or not enforced by their elected counterparts, they may have an incentive not to stray too far from public opinion (e.g., Reference Epstein and KnightEpstein & Knight 1998; Reference Stimson, MacKuen and EricksonStimson, MacKuen, & Erickson 1995). To be sure, the justices only share policymaking authority with the other branches of government. Should they stray too far from public opinion on an issue, it is likely that the legislature may attempt to alter or override their decision or the executive may indifferently enforce the decision. Such a concern could induce the justices to carefully consider public opinion surrounding a case.

Second, it has been noted that the justices may be influenced by public opinion to ensure the institutional legitimacy of the Court (e.g., Reference Flemming and Dan WoodFlemming & Wood 1997; Reference Mishler and SheehanMishler & Sheehan 1993). With neither the purse nor the sword, the justices must rely on the goodwill of the citizenry to follow its decisions (and the executive to enforce them). Should the justices ignore the views of the public, it is likely that the Court will lose some of its institutional legitimacy and support. In addition, by deciding a case in line with the litigant supported by the largest number of interest groups, the justices may not only be influenced by interest group opinion on an issue, but may in turn use this in an attempt to shape public opinion themselves. In this sense, just as Chief Justice Marshall used newspaper space to respond to his critics (Reference BeveridgeBeveridge 1947), the justices may use interest group opinion on an issue to reassure the public that the Court is responsive to its demands.

The number of interest groups appearing on amicus briefs provides a reasonable, albeit crude, gauge of public opinion on a case for at least two reasons. First, because such briefs are targeted at the issues surrounding a particular case, they enable the justices to make precise calculations regarding public opinion on the issue. Thus, unlike opinion polls that are necessarily staggered in nature and may not touch on issues of contemporary relevance to the Court, amicus briefs are aimed at specific cases and issues before the Court. Second, because these briefs are filed and signed by interest groups, the number of groups cosigning such briefs may serve as a reliable indicator to the justices as to the number of potentially affected individuals. Surely the justices are aware of the major role interest groups play in electoral politics by mobilizing voters, making campaign donations, and informing elected officials in regard to their causes. If they fear a congressional override or executive noncompliance, they may well consider the number of groups supporting a particular litigant in a given case.

Because the affected groups theory of the influence of amicus briefs ignores the vast amount of information that briefs contain, other than the number of affected groups and their preferred dispositions, it is advantageous to establish at least indirect evidence that the justices consider the number of potentially affected groups as useful knowledge. However, this task is complicated by the fact that the Court traditionally refers, in its opinions, to joined amicus briefs simply by the first organization's name followed by “et al.”Footnote 9 Nonetheless, some evidence does exist. For example, in Webster, Justice Blackmun referred to the brief of “167 Distinguished Scientists and Physicians, including 11 Nobel Laureates” (109 S. Ct. 3040, at 3076), while Justice Stevens made reference to the brief for the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod as being filed “on behalf of 49 ‘church denominations’” (109 S. Ct. 3040, at 3082); later, he referred to the “67 religious organizations [that] submitted their views as amici curiae on either side of the case” (109 S. Ct. 3040, at 3085).Footnote 10

Similarly, in School Board of Nassau County v. Arline (1987), Justice Brennan, rather than using the traditional “et al.,” referred to state amici California, Maryland, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, and Wisconsin, all of whom joined a single brief, individually. Justice Powell made a similar distinction in Regents of California v. Bakke (1978), referring to the joint brief of Columbia University, Harvard University, Stanford University, and the University of Pennsylvania, listing each amicus individually. While this is far from definitive evidence for the affected groups theory, at a minimum it suggests that the justices are conscious of, and pay attention to, the number of participants on the briefs. Simply put, the above examples illustrate that the justices may genuinely care about the number of participants on a brief when reaching their decisions and writing their opinions.

Kearney and Merrill provide an excellent synopsis of the affected groups theory:

Insofar as the Justices are assumed to try to resolve cases in accordance with the weight of public opinion, they should look to amicus briefs as a barometer of opinion on both sides of the issue. Moreover, the information that amicus briefs convey about organized opinion is such that it can largely be assimilated simply by looking at the cover of the brief. The Justices can scan the covers of the briefs to see which organizations care strongly about the issue on either side. The fact that the organization saw fit to file the brief is the important datum, not the legal arguments or the background information set forth between the covers of the brief (2000:785, emphasis added).

Thus, the affected groups hypothesis holds that it is not the social scientific, legal, or political arguments briefs contain that influence the Court, but instead the mere presence of a large number of interests on one side of the dispute relative to the other. Given this argument, if the justices legitimately consider affected groups in their decisionmaking, we would expect litigants with more amicus participants on their side, relative to their opponents, to have an increased probability of victory. Therefore:

Affected Groups Hypothesis: An advantage of amicus participants, relative to one's opponent, will increase the likelihood of litigation success.

An alternative explanation for the influence of amicus briefs, information theory, holds that amicus briefs are effective not because they act as a barometer of public sentiment, but instead because they supply the justices with information that serves to supplement the arguments in the briefs of the parties.Footnote 11Reference Spriggs and WahlbeckSpriggs and Wahlbeck (1997) find that more than 65% of amicus briefs filed in the 1992 term included information not found in the briefs of the direct parties. “Frequently, this additional information presents the dispute from another legal perspective, discusses policy consequences, or comments on the norms governing the interpretation of precedent and statutes” (Reference Spriggs and WahlbeckSpriggs & Wahlbeck 1997:372). Rustad and Koenig note, “The most common method of introducing social science evidence to the [Supreme] Court is through ‘non-record evidence’ in amicus curiae briefs” (1993:94). In addition, Reference Epstein and KnightEpstein and Knight (1999) find that amicus briefs often inform the Court of the preferences of other actors, such as Congress and the executive. In this sense, amicus briefs offer the justices legal, social scientific, and political information; information found only within the covers of those briefs.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that the justices consider this information relevant. For example, in Mapp v. Ohio (1961) the Court applied the exclusionary rule to the states. However, none of the briefs of the direct litigants to the suit raised the suppression issue. Instead, it took the amicus brief of the American Civil Liberties Union to provide this information (Reference DayDay 2001; Reference McGuire and PalmerMcGuire & Palmer 1995). Thus, had it not been for an amicus brief in Mapp, the issue of the exclusionary rule may never have been broached by the Court. Indeed, Mapp is not alone. For example, similar arguments have been made for the import of amicus briefs in shaping the justices' opinions in Webster (Reference Behuniak-LongBehuniak-Long 1991; Reference KolbertKolbert 1989), Davis v. Monroe County Board of Education (1999) Reference Sungaila(Sungaila 1999), and Teague v. Lane (1989) Reference Munford(Munford 1999), to name but a few examples.

More directly relevant to this analysis is the possibility that the more amicus briefs filed on behalf of a party, relative to its opponent, the greater the number of legal arguments presented, or alternatively framed, on behalf of that party. Given this, a justice not willing to discover an issue for him/herself may seek out the issue in amicus briefs (similar to Mapp). Analogously, a justice not particularly pleased by the arguments of the direct party to litigation, but leaning toward supporting a disposition favoring that party, may do so because of arguments found in an amicus brief in support of that party. In other words, a large number of amicus briefs filed on behalf of a given party present the Court with numerous alternative and reframed arguments; all of this may result in an increased likelihood of victory for the party with the relative advantage of briefs.Footnote 12 Therefore:

Information Hypothesis: An advantage of amicus briefs, relative to one's opponent, will increase the likelihood of litigation success.

Research Design and Methodology

Segal and Spaeth provide an important caution regarding examining the influence of interest groups on the Court: “Before influence can be inferred, we must show that an actor in the Court's environment had an independent impact after controlling for other factors” (1993:237). Thus, in order to determine if a relative advantage of both amicus briefs and amicus participants increases litigation success, we must simultaneously control for alternative explanations.Footnote 13

The data on litigation success come from Spaeth's (1999) United States Supreme Court Judicial Database, 1953–1997 Terms. I consider all orally argued cases formally decided on the merits from this dataset, excluding those cases decided by a tie vote and falling under the Court's original jurisdiction, during the Warren and Burger courts (1953–1985). I use the docket number as the unit of analysis because the Court does not necessarily dispose of all cases decided with a single opinion in the same manner (Reference Segal and SpaethSegal & Spaeth 1993:194). I merge these data with data from the United States Supreme Court Judicial Database, Phase II, which provides the amount of organizational amicus participation during this time frame.Footnote 14 While it would be optimal to consider amicus participation beyond this time frame, unfortunately, the United States Supreme Court Judicial Database, Phase II, only includes amicus participation from 1953 to 1985.

In order to determine what effect, if any, a relative advantage of amicus briefs and amicus participants has on litigation success, I estimate a model of petitioner success. Because the dependent variable, petitioner win, is dichotomous (where 1=petitioner win),Footnote 15 I employ a logit model.Footnote 16 To determine the influence of a relative advantage of amicus briefs and amicus participants on litigation success, I utilize four variables. Petitioner Amicus Briefs and Respondent Amicus Briefs are simply the number of briefs filed for the petitioner and respondent, respectively. Similarly, Petitioner Amicus Participants and Respondent Amicus Participants Footnote 17 represent the number of interest groups appearing on each amicus brief supporting either the petitioner or respondent.Footnote 18

To control for the well-documented success of the Office of Solicitor General as amicus curiae (Reference Caldeira and WrightCaldeira & Wright 1988; Reference Deen, Ignagni and MeernikDeen, Ignagni, & Meernik 2003; Reference SegalSegal 1988), two variables are included, SG Amicus Supporting Petitioner and SG Amicus Supporting Respondent, scored one if the Office of Solicitor General filed an amicus brief on behalf of the petitioner or respondent, respectively, and zero otherwise. An amicus brief filed by the Solicitor General on behalf of the petitioner is expected to increase the petitioner's likelihood of success, while an amicus brief filed on behalf of the respondent by the Solicitor General is expected to decrease the petitioner's likelihood of success.

To control for the changing ideological composition of the Supreme Court during the thirty-two years of this study, I utilize an Ideological Congruence measure based on the individual justice's ideology scores developed by Reference Segal and CoverSegal and Cover (1989),Footnote 19 and the liberal or conservative nature of the lower court's disposition in a given case. This measure is coded one if the lower court's disposition was identified in Spaeth's database (1999) as being liberal and the mean ideology score of the Court is negative (indicating a conservative Court).Footnote 20 Similarly, if the lower court's disposition was conservative and the mean ideology of the Court is positive, this score is also coded one. Thus, if the lower court's disposition is identified as conservative and the mean ideology of the Court is negative, this score is coded zero. Finally, if the lower court's disposition is liberal and the Court's mean ideology score is positive, this variable is coded zero. This variable is intended to capture the fact that the petitioner has argued a liberal (conservative) position before a liberal (conservative) Court. Thus, the expected sign of this variable is positive, indicating that arguing a position congruent with the mean ideology of the Court increases the petitioner's likelihood of success.

Scholars have long noted the import of party resources in measuring litigation success (Reference GalanterGalanter 1974; Reference Sheehan, Mishler and SongerSheehan, Mishler, & Songer 1992; Reference Songer, Kuersten and KahenySonger, Kuersten, & Kaheny 2000; Reference Wheeler, Cartwright, Kagan and FriedmanWheeler et al. 1987). To control for litigant resources, I utilize the status continuum of litigants adopted generally from Reference Sheehan, Mishler and SongerSheehan, Mishler, and Songer (1992); see also Reference McGuireMcGuire (1995, Reference McGuire1998) and Reference Wheeler, Cartwright, Kagan and FriedmanWheeler et al. (1987). That is, I rank litigants, according to increasing resources, as follows: poor individuals=1, minorities=2, individuals=3, unions/interest groups=4, small businesses=5, businesses=6, corporations=7, local governments=8, state governments=9, and the federal government=10.Footnote 21 From this continuum, I calculate the variable Resources on the basis of the two parties in a suit by simply subtracting petitioner resources from respondent resources. Thus, when the case involves the federal government as petitioner and a state government as respondent, the resource differential is 1. Similarly, when a union is the petitioner facing a federal government respondent, the resource differential is −6, indicating that unions rank lower on the status continuum than the federal government. When two groups of the same issue type are facing each other as petitioner and respondent this score equals 0, indicating that neither litigant is advantaged by superior resources. While this scoring may be suboptimal because it relies on the use of such broad categories, it nonetheless serves as a parsimonious manner to account for the impact of resources in Supreme Court litigation and has been used successfully in earlier studies (e.g., Reference McGuireMcGuire 1995, Reference McGuire1998; Reference Sheehan, Mishler and SongerSheehan, Mishler, & Songer 1992). The expectation is that the sign of this variable will be positive, indicating that petitioners with more resources than their opponent are more likely to prevail on the merits.

Finally, because petitioner success is what is being explained, two additional control variables are included to account for the Supreme Court's well-established practice of reversing lower court decisions, thus ruling in favor of the petitioner. Scholars have long recognized the Court's tendency to grant certiorari in cases it seeks to reverse (Reference PerryPerry 1991; Reference SchubertSchubert 1959; Reference Segal and SpaethSegal & Spaeth 1993). To control for this, a Certiorari variable is utilized, scored one if the case was placed on the Court's docket via a grant of certiorari and zero if it reached the Court under its mandatory jurisdiction.Footnote 22 It is expected that this variable will be positive, indicating that the Court is more likely to reverse (thereby ruling for the petitioner) cases that come to it on a grant of certiorari than on obligatory appeal. In addition, Reference Segal and SpaethSegal and Spaeth (1993:200–2) find that the Court's reversal rates for cases granted certiorari are reduced when the Court's reason for granting the writ is the existence of lower court conflict. To control for this fact, I also include the variable Lower Court Conflict, in the model.Footnote 23 This variable is scored one if the case was accepted on certiorari and lower court conflict is identified in Spaeth's database (1999) as the reason for granting the writ, and zero otherwise. It is expected that this variable's sign will be negative, indicating that, when lower court conflict exists, the Court is less likely to reverse the lower court (thereby ruling for the respondent) than when no such conflict is present.

Results

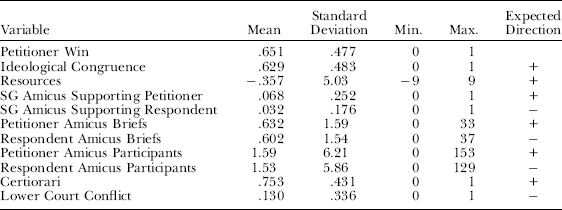

Table 1 reports the summary statistics for both the dependent and independent variables, as well as the expected direction for each of the independent variables. Worthy of note is that, on average, petitioners and respondents are supported by the same number of amicus briefs and participants. This is fascinating because, if interest groups choose to participate more frequently in cases they believe they are likely to win, we would expect the vast majority of amicus participation to side with the petitioner, who enjoys a well-recognized advantage over the respondent (Reference Segal and SpaethSegal & Spaeth 1993:194–201). However, these summary statistics suggest that this is not the case.Footnote 24 Thus, Table 1 seems to indicate that interest groups do not select “winners” to join, but instead participate nearly equally for both petitioners and respondents.

Table 1. Summary Statistics

To further test for the possibility that amici are a priori more likely to file briefs with the winning side (in order to be perceived as winners themselves), I ran the logit model reported in Table 2 without the amicus curiae variables and saved the model's predictions. I then determined the average number of briefs filed on behalf of predicted winners and losers. The results indicate that the mean number of amicus briefs filed in support of the predicted winners is 0.619, and the mean number of amicus briefs filed in support of predicted losers is 0.615. A t-test confirmed the difference between these means as insignificant. To further investigate whether groups select likely winners to support, I ran the same t-test reported above but included only cases in which at least one amicus brief was filed (N=1,981). These results indicate that the average number of briefs filed in support of predicted winners is 1.51 and 1.50 for predicted losers. Again, a t-test confirmed the difference between these means as insignificant. These tests provide evidence that amici do not self-select winners, or that they are not very good at it if they do, for two reasons. First, although excluding the amicus variables, this model is reasonably well specified, certainly in terms of previous research (e.g., Reference Sheehan, Mishler and SongerSheehan, Mishler, & Songer 1992). Second, although this model is somewhat complicated, as with any maximum likelihood model, organized interests seeking to select likely winners to support may surely be aware of information regarding the lower court's disposition of the case, the Court's reason for granting certiorari, litigant resources, and the Court's ideological makeup. As such, it appears that interest groups do not file briefs solely on behalf of the litigants they believe will win, but instead on behalf of litigants whose positions they genuinely support, regardless of their probability of litigation success.Footnote 25

Table 2. Logistic Regression Model for Petitioner Success, 1953–1985 Terms

Numbers in parenthesis indicate robust standard error of estimate, clustered on case citation. *p≤.10;**p≤.01 (one-tailed).

Marginal Impact is calculated as the change in predicted probability given discrete change from 0 to 1 for dichotomous variables and change to one standard deviation above the mean for continuous variables, holding all other variables at their mean or modal value.

Table 2 reports the results of the logistic regression model.Footnote 26 The model correctly predicts almost 70% of outcomes, for a percent reduction in errorFootnote 27 of almost 6%.Footnote 28 More notably, the model illuminates an important finding regarding the affected groups vis-à-vis the information hypothesis. Specifically, the model shows strong support that it is amicus brief support that increases the probability of litigation success, and not amicus participant support. Consequently, it appears the Court values the information found within amicus briefs and not the information found on the covers of these briefs. In addition, the model reveals that amicus brief support benefits respondents more than petitioners, though the difference is rather marginal.

Not surprisingly, the results in Table 2 also lend strong support for the Solicitor General's role as the quintessential repeat player in Supreme Court adjudication. Similar to interest group amicus briefs, the results indicate that an amicus brief filed by the Solicitor General plays a greater role for respondents than for petitioners. This finding is supportive of Kearney and Merrill's assertion that high-quality amicus briefs may be more beneficial to respondents than petitioners because “respondents are more likely than petitioners to be represented by inexperienced lawyers in the Supreme Court and hence are more likely to benefit from supporting amici, who can supply the Court with additional legal arguments and facts overlooked by the respondent's lawyers” (2000:750).

The model also provides strong support for the role of both ideology and resources in litigation success. When a petitioner of a certain ideology argues that position before a Court of the same ideology, the likelihood of success increases ten percentage points. As to resources, when a petitioner faces a respondent one step below the status continuum reported above, an approximately 1.2% increase in the likelihood of victory exists. For example, when the federal government as the petitioner faces an individual respondent, the government can expect to enjoy an increased probability of victory of almost 5%, as compared to a situation in which the federal government squares off against a corporation as respondent.

Finally, both of the control variables, Certiorari and Lower Court Conflict, are signed in the expected direction and statistically significant. Certiorari indicates that the Court is more likely to reverse cases accepted on a writ of certiorari than cases arriving at the Court under their mandatory jurisdiction. However, when lower court conflict exists and the case was accepted on a writ of certiorari, the variable Lower Court Conflict indicates that Court is far less likely to reverse the decision of the lower court from which the writ of certiorari originated.

To recall, both the affected groups and information hypotheses posit that a relative advantage of amicus support will benefit litigants. To more clearly see the substantive effects uncovered by the logit estimation, Table 3 reports the probabilities of petitioner success varying only the Petitioner Amicus Briefs and Respondent Amicus Briefs variables, while holding all other variables at their mean or modal values.Footnote 29 This table reveals two important findings.

Table 3. Select Predicted Probabilities of Petitioner Success with Amicus Brief Advantages

Predicted probabilities are calculated varying only the Petitioner Amicus Brief and Respondent Amicus Brief variables, holding all other variables at their mean or modal values.

First, Table 3 reveals that the influence of amicus briefs on litigation success is rather marginal. In particular, when a single amicus brief is filed on behalf of the petitioner and no briefs are filed on behalf of the respondent, the petitioner's probability of success increases less than two percentage points. When the situation is reversed (no briefs are filed in support of the petitioner and one brief is filed on behalf of the respondent), the petitioner's probability of success decreases by more than two percentage points. Thus, although amicus briefs benefit respondents more than petitioners, the difference is somewhat trivial.

Second, Table 3 provides support for the argument that it is a relative advantage of amicus briefs that benefits litigants. However, there is a differential effect. For example, when three briefs are filed on behalf of the petitioner and no briefs are filed on behalf of the respondent, the petitioner's probability of success increases more than five percentage points (77.1%). When the petitioner enjoys the same relative advantage of three briefs, but in a different combination, these results differ. For instance, when twelve briefs are filed on behalf of the petitioner and nine briefs are filed on behalf of the respondent, the petitioner's probability of victory drops to 74.8%. To be sure, this is not to say that a litigant is ever disadvantaged as a result of having a great deal of briefs filed on its behalf relative to its opponent. Instead, these results suggest that, as the number of amicus briefs increases, these briefs are likely to reiterate the arguments of the supported litigant and/or of the fellow amici, and the Court seemingly takes notice of such reiteration.

Discussion

With results indicating that cosigning amicus briefs does not play a statistically significant role in increasing litigation success, a consideration of why groups choose to pursue this method of participation is clearly warranted. While it is well recognized that the primary goal of interest group participation as amicus curiae is to influence the Court's policy output (Reference Epstein and RowlandEpstein & Rowland 1991; Reference HansfordHansford 2004; Reference KoshnerKoshner 1998; Reference KrislovKrislov 1963; Reference Spriggs and WahlbeckSpriggs & Wahlbeck 1997), secondary goals and motivations also exist. Near the top of this list is a consideration of group resources. Despite the frequency with which it is done, filing amicus curiae briefs is not an inexpensive means of participation (Reference Caldeira and WrightCaldeira & Wright 1988:112). Not all groups are likely to have, or be willing to expend, the resources to file a separate brief. By joining briefs prepared by other amici or by sharing the costs of a single brief among a few organizations, groups can participate in Supreme Court adjudication without taking on heavier financial burdens themselves.

In addition, “Alliances also offer groups a low-cost way of showing members … that they are active on issues” (Reference HojnackiHojnacki 1997:66). It is evident that group maintenance is one of the primary concerns of interest groups (Reference MoeMoe 1980; Reference OlsonOlson 1965; Reference WasbyWasby 1995). One of the chief concerns for membership-based organizations is their ability to attract new members while preserving their current base of support. While it is well known that such groups utilize selective incentives to generate and maintain their membership base (Reference OlsonOlson 1965), many groups also rely on purposive benefits to achieve this goal (Reference King and WalkerKing & Walker 1992; Reference MoeMoe 1980). “To provide purposive incentives, a group needs to make its members feel that the group is actively pursing its stated policy goals and successfully influencing policy outcomes” (Reference HansfordHansford 2004:222). A low-cost method of achieving this goal, relative to filing an individual amicus brief, is to cosign briefs prepared by other organizations. Through this, groups can illustrate to their members that they are active participants in the judicial arena and, should they perceive some measure of success, they can claim some of the credit as well.

Finally, and perhaps most important, groups may join amicus briefs to build relations with like-minded organizations. As Wasby observes, highly salient civil rights cases exist “in which ‘all join’ because it ‘is important for the civil rights bar to show it feels strongly about the importance of an issue’” (1995:233). Similarly, like-minded groups may also perceive unique benefits from these types of coalitions. Epstein documents that the National District Attorneys Association (NDAA) and Americans for Effective Law Enforcement (AELE) participate as amicus curiae almost exclusively jointly and that “[T]his relationship has been mutually beneficial; NDAA's briefs have become more meaningful because of AELE attorneys' expertise and use of social science evidence, while NDAA support linked AELE with a repeat-player in its first appearances before the Court” (1985:114).Footnote 30

Given that coalitional amicus briefs allow organizations to participate and claim credit while expending a minimal amount of resources, as well as further their relationships with like-minded organizations, it should be no surprise that coalitional amicus activity is a staple of interest group participation in the Court. And while not all groups opt for this method of participation,Footnote 31 it is likely that we will continue to see coalitional amicus activity proliferate in the Court.

In addition to the above discussion of the negative finding regarding amicus participation and litigant success, a discussion of the implications of the positive finding regarding amicus briefs and party success is warranted. First, these results suggest that, while amicus briefs do increase litigation success, even when controlling for other more established influences, this influence is only marginal. However, it is clear that the influence of the Solicitor General's amicus briefs is far from trivial. Such a finding has at least two implications. First, it suggests that the Court may be deferential to the interests of the executive branch (see also Reference Puro and UlmerPuro 1981; Reference SciglianoScigliano 1971; Reference YatesYates 2002). Second, and perhaps more important, it suggests that the prestige of amicus participants may be vital to success in the Court. For instance, Reference McGuireMcGuire (1998) provides compelling evidence that, once litigation experience is controlled for, the success of the Solicitor General is in no way distinct from the success of other, equally experienced attorneys. Applying this to the present analysis, we might expect that highly experienced amici, such as the American Civil Liberties Union and the Pacific Legal Foundation, might be equally well off. Clearly, future research in this area may well benefit from such a consideration.Footnote 32

Finally, the present analysis has bearing on perhaps the most important area of Supreme Court scholarship: judicial decisionmaking.Footnote 33 The results in this article speak to the fact that the attitudinal model (e.g., Reference Segal and SpaethSegal & Spaeth 1993) may not present a complete picture of litigant success in the Court. While ideological factors do play an important role in party success before the Court, these results indicate that so too do legal factors. Specifically, the findings presented suggest that the addition of outside counsel, in the form of amicus briefs, may aid a party in better realizing its litigation objectives. Further, the results here suggest that the justices do not respond to the influence of interest group opinion, at least on a case-by-case basis. As such, I believe that judicial scholars may be better served by approaching Supreme Court decisionmaking as a complex phenomenon, perhaps best explained through the integration of numerous approaches, rather than by outright adopting a particular perspective on the choices justices make.

Conclusion

This article has made two modest contributions to our understanding of interest group activity and litigation success in the Supreme Court. First, it is one of the few studies to have rigorously analyzed amicus participation and effectiveness on a large-scale basis. The numerous other studies examining this phenomenon are generally either focused on a few groups (Reference EpsteinEpstein 1985; Reference Ivers and O'ConnorIvers and O'Connor 1987; Reference O'ConnorO'Connor 1980; Reference PuroPuro 1971) or specific issue areas (Reference McGuireMcGuire 1990; Reference VoseVose 1967; Reference WasbyWasby 1995), or do not control for established influences on litigation success (Reference Kearney and MerrillKearney & Merrill 2000; compare with Reference McGuireMcGuire 1995; Reference Songer and SheehanSonger & Sheehan 1993).Footnote 34 Second, by examining and testing two alternative, though not mutually exclusive, accounts of why amicus briefs might be an efficacious tool for interest groups in the Court, this research has contributed to our theoretical understanding of why amicus briefs increase litigation success.

That said, I do caution the reader regarding the utility of the affected groups hypothesis as operationalized here. Specifically, while I am confident in the results that a relative advantage of amicus participants does not increase the likelihood of litigation success, I am hesitant to call the affected groups hypothesis lifeless. Here I have assumed that an advantage of amicus briefs, relative to one's opponent, represents the fact that the litigant possesses more opportunities to present the Court with alternative or reframed arguments than does the litigant's opponent. While I doubt this assumption is completely unjustified, I nonetheless recognize the fact it is not operationalized. Thus, I believe it is imperative to acknowledge that fact that it still may be affected groups that increase litigation success.

In particular, it is possible that the Court reacts to affected groups in the form of briefs and not participants. If the Court believes that the number of participants on a brief is a less credible information source than the number of briefs filed, it may simply be responding to the number of briefs filed as indicative of affected groups. In other words, if the Court considers the amount of resources interest groups spend as indicative of truly potentially affected groups, and if the costs of filing an amicus brief are within a relatively homogeneous range, then we would expect the Court to consider the number of briefs filed as a proxy for the amount of resources expended and not the number of participants on a brief (Reference Kearney and MerrillKearney & Merrill 2000:787). Thus, the Court may be reacting to affected groups in terms of resources expended (estimated through the relative number of briefs filed on behalf of each litigant) and not the relative number of participants joining briefs. Clearly though, this would ignore the vast amounts of legal, social scientific, and political information that briefs contain—information the justices themselves have acknowledged can be useful (Reference BreyerBreyer 1998; Reference DouglasDouglas 1962). Nonetheless, I believe the current research has contributed to our understanding of amicus participation and litigant success, and I leave a deeper exploration into this alternative account of the affected groups hypothesis for further research.

An additional limitation of this analysis is the fact that it only examines amicus activity during the Warren and Burger courts. It is possible that the recent and dramatic increases in amicus filings in the Supreme Court have resulted in a “routinization” of how amicus briefs are considered by the Court. In other words, the fact that amicus participation is now present in almost every case heard by the Court may have changed how these briefs are taken into account. Undoubtedly, this is an area ripe for examination and is likely to be a subject of both theoretical and empirical interest to scholars of both interest groups and the judiciary. Thus, a resurgence of quality scholarship on amicus participation may be of benefit to scholars of both the judiciary and interest groups and will likely lead us toward a better understanding of the motivations and impact of friends of the court.