INTRODUCTION

As inventory shortages wreak havoc on the global economy, the world is once again faced with the complexities and vulnerabilities inherent in supply chains. Yet, to human rights advocates, this is nothing new. Companies have long had to manage the risk of human rights violations being committed by their third-party suppliers. Considering companies’ largely ineffective attempts at self-regulation (Ruggie Reference Ruggie2013), governments have passed a variety of mechanisms to seek corporate accountability, ranging from intergovernmental instruments and supranational law to mandatory domestic legislation. Recent legal efforts to govern global supply chains have centered around a single practice—namely, “human rights due diligence”—which is aimed at identifying, preventing, mitigating, and accounting for potential adverse human rights impacts.

While initially an ambiguous and vague concept when it was introduced by the United Nations (UN) in 2011, human rights due diligence is now the cornerstone of the international legal framework to regulate corporate activity related to human rights (Landau Reference Landau2019). It has evolved into an international legal norm whose meaning is being interpreted on the ground by corporate actors themselves. Articulated in a variety of legal instruments, the norm of human rights due diligence is taking shape in the technical practices of expertsFootnote 1 and under the leadership of industry associations. Drawing on industry standards, experts conduct supply chain mapping and risk assessments by applying auditing tools, indicators, and other management techniques. Yet corporate-designed templates for carrying out human rights due diligence are not just industry best practice. They have become the dominant standard for implementing domestic law on mineral supply chains (specifically, section 1502 of the US Dodd-Frank Act of 2010) and have been explicitly recommended by the European Union (EU) to implement its conflict minerals regulation (EU Regulation 2017/821).Footnote 2 It is therefore critical to analyze the role of industry in interpreting the international legal norm of human rights due diligence.

In this article, we demonstrate that global supply chains are being “governed at a distance,” borrowing from the framework of social theorists Nikolas Rose and Peter Miller (Reference Rose and Miller1992). In other words, governments are outsourcing the power to regulate supply chains to certain industry associations, which are governing at a distance by means of audits, checklists, and other technocratic tools. We find that supply chain governance at a distance stands in contrast to the stated goals of human rights due diligence. Rather than establishing relationships of accountability, supply chain governance at a distance is creating an “ethic of detachment” whereby companies are able to separate themselves legally, morally, and socially from responsibility to their suppliers (Cross Reference Cross2011).

Our analysis draws on a case study of a multi-industry association called the Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI), which has assumed a leading role in implementing conflict minerals legislation and interpreting the norm of human rights due diligence in mineral supply chains. Established in 2008, the RMI was founded by companies to manage sourcing risks in Central Africa’s tin, tungsten, tantalum, and gold sectors (collectively referred to as “conflict minerals”). Among those risks was a concern that conflict minerals provided funding to armed groups in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). As of 2023, the RMI has grown to more than four hundred corporate members in such industries as electronics, automotive, aerospace, jewelry, and communications. The organization evolved to fill a vacuum left by the US government in 2010 when it passed conflict minerals legislation (section 1502 of the US Dodd-Frank Act), which lacked sufficient guidance on how to implement its extraterritorial provisions. The RMI has since assumed a leading role in implementing this law, as well as similar legislation passed by the EU, by developing a reporting template and auditing standards that target what are considered to be supply chain choke points—the smelters and refiners often located abroad (SEC 2012). The RMI’s tools give meaning to the international legal norm of human rights due diligence in the context of mineral supply chains.

Drawing on interviews with RMI staff, corporate representatives, and independent members of the RMI’s governance committees, as well as participant observation within the RMI,Footnote 3 we analyze the industry association’s role in implementing regulations on global mineral supply chains and interpreting the norm of human rights due diligence. We focus on the RMI’s Risk Readiness Assessment (RRA), which is an online self-assessment and due diligence tool for companies to identify and assess environmental, social, and governance risks across fifteen minerals and metals in raw material supply chains. We demonstrate that, while the RMI’s tools provide companies with helpful guidance, they mask the underlying corporate interests that control how human rights due diligence is being interpreted and implemented on the ground. The RRA is based on general and sometimes vague categories as well as rankings that lack substantial differentiation. In addition, there is no independent verification of information disclosed by companies or their evaluation of supply chain risks, thus resulting in a lack of accountability to external stakeholders. Based on our analysis, we argue that human rights due diligence is being transformed from an instrument of corporate accountability to a tool of corporate legitimacy.

The remainder of this article proceeds as follows. We first review existing scholarship on the role of corporations in shaping transnational governance. We then track the emergence of human rights due diligence from an ambiguous and broadly defined concept referenced in soft law instruments to a legal norm that has been incorporated into recent domestic legislation. After reviewing existing international standards and binding legislation on the responsible sourcing of mineral supply chains, we demonstrate that gaps remain as to how the norm of human rights due diligence is interpreted in practice. We then analyze the role of the RMI in filling this vacuum by providing critical guidance on how to identify and assess risks in global supply chains. We argue that the RMI’s technocratic tools are enabling corporations to exercise considerable influence over the interpretation of the legal norm of human rights due diligence. As a result, global supply chains are being governed at a distance and fostering an ethic of detachment that enables corporations to manage, control, and limit their attachments to their suppliers and thereby deflect accountability.

HOW CORPORATIONS SHAPE TRANSNATIONAL GOVERNANCE

While corporations have long played an important role in transnational governance, their influence has grown as multinational companies wield significant power over state and international politics (Ruggie Reference Ruggie2007). Scholars have long examined the role of non-state actors such as non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in transnational lawmaking (see, for example, Braithwaite and Drahos Reference Braithwaite and Drahos2000; Abbott and Snidal Reference Abbott and Snidal2009; Halliday and Block-Leib Reference Halliday and Block-Leib2017). The literature has also focused on corporate influence in the development of public and private international law (Danielsen Reference Danielsen2005; Shaffer Reference Shaffer2009; Alvarez Reference Alvarez2011; Stephan Reference Stephan2011; Arato Reference Arato2015; Durkee Reference Durkee2017). The case of the RMI contributes to this literature by uncovering the role of industry associations in implementing transnational law and interpreting international legal norms.

Corporate participation in transnational governance has taken many forms and focused on a variety of actors. Businesses shape transnational lawmaking through multiple mechanisms, including lobbying legislators for policy changes, exerting influence over administrative rule making, and using litigation to affect the interpretation of laws over time (Shaffer Reference Shaffer2009). Corporations are also engaged in the transnational diffusion of law through the exportation of industry codes of conduct and other private standards, which has influenced the development of domestic and international regulations (Braithwaite and Drahos Reference Braithwaite and Drahos2000). Scholarship has examined the role of business entities in the making of international rules governing such areas as trade, investment, antitrust, intellectual property, and telecommunications (Alvarez Reference Alvarez2011). It has analyzed the influential role of corporations in the international treaty-making process, including their design, drafting, negotiation, adoption, ratification, and implementation (Durkee Reference Durkee2016).

While existing scholarship is devoting increased attention to the important role of corporations in transnational governance, it rarely disaggregates businesses in order to analyze the differential role of various institutional forms of corporate organization. These organizational structures include corporations, partnerships, sole proprietorships, and limited liability companies. Multiple firms can also join together to form such corporate entities as industry associations. These organizations usually are non-profit and are designed to promote the common business interests of their members. Although industry associations serve as important political actors engaged in policy making, their role in interpreting international legal norms is under-researched in the international law and transnational governance literature.

Scholars are beginning to explore how industry associations serve as lawmakers as part of transnational legal processes (Shaffer and Durkee Reference Shaffer and Durkee2017). Recent work has highlighted a variety of roles being played by these actors, including lobbying to gain access to, and shape policy making by, governments and international organizations (Durkee Reference Durkee2017); helping to develop legal rules by providing input to decision makers that builds on sector-specific expertise (Karton Reference Karton2017); and transnational standard setting to reflect industry preferences (Abbott and Snidal Reference Abbott and Snidal2009; Büthe and Mattli Reference Büthe and Mattli2011; Berman Reference Berman2017). Scholarship has recently emphasized how industry associations are participating in the process of international legal interpretation. Drawing on their unique expertise and privileged access, industry associations engage in a form of “post hoc lawmaking” by shaping the meaning of international legal norms (Durkee Reference Durkee2021).

Building on recent work, this article contributes to existing literature in international law by examining how an influential multi-industry association is shaping the interpretation of international legal norms (specifically, the norm of human rights due diligence) and the implementation of transnational law (specifically, supply chain due diligence laws with respect to conflict minerals). We draw on a socio-legal approach that focuses on the technical practices of transnational supply chain governance (see, for example, Riles Reference Riles2005, Reference Riles2011; Johns Reference Johns2017; Sullivan Reference Sullivan2017). Our study of the RMI also contributes to the business and human rights literature by uncovering how emerging regulation on human rights due diligence is failing to achieve its purported goal of enhancing corporate accountability. The RMI has assumed a leading role in implementing supply chain legislation and designing tools to carry out human rights due diligence—tools that are enabling corporations to assess their own performance based on shallow indicators and the disclosure of information that is not independently verified. The RMI’s risk assessment tools demonstrate how supply chains are being governed at a distance, thereby disrupting relationships of accountability between companies and their suppliers.

THE EMERGENCE OF THE INTERNATIONAL NORM OF HUMAN RIGHTS DUE DILIGENCE

Human rights due diligence has evolved from an ambiguous and broadly defined concept referenced in soft law instruments to a legal norm that has been cited in recent domestic legislation and is currently taking shape in corporate practice. The norm of due diligence was originally transplanted into international human rights law from the fields of general international law and corporate governance. As a principle of international law, due diligence refers to the level of effort that a responsible state ought to perform to fulfill its international obligations (see Krieger, Peters, and Kreuzer Reference Krieger, Peters and Kreuzer2020). In corporate governance, due diligence is used as a standard of care in corporate risk assessments in the context of financial and commercial transactions (Lambooy Reference Lambooy2010). While human rights due diligence originally referred to states’ obligations to respond to human rights violations committed by non-state actors, it was later applied specifically to companies and began to appear in corporate codes of conduct starting in the mid-1990s (Martin-Ortega Reference Martin-Ortega2013, 53–55). Unlike conventional corporate due diligence procedures that focus on risks to business, human rights due diligence aims to identify, prevent, mitigate, and account for risks to people affected by a company’s activities.

The first legal document to cite human rights due diligence with reference to corporate conduct was the UN Norms on the Responsibilities of Transnational Corporations and other Business Enterprises with Regard to Human Rights (UN Norms). Even though the UN Norms failed to be approved by the then UN Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights, the commentary to Article I established due diligence as the standard for companies: “Transnational corporations and other business enterprises shall have the responsibility to use due diligence in ensuring that their activities do not contribute directly or indirectly to human rights abuses, and that they do not directly or indirectly benefit from abuses of which they were aware or ought to have been aware.”Footnote 4

Yet it was not until 2011 when human rights due diligence was incorporated into the main text of a UN legal document, the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (Guiding Principles).Footnote 5 Unanimously endorsed by the UN Human Rights Council, the Guiding Principles have become the dominant framework for articulating international legal responsibilities with respect to business and human rights. The Guiding Principles rest on three pillars: (1) the state duty to protect human rights; (2) the corporate responsibility to respect human rights; and (3) the need for access to remedies for victims of human rights abuses. While the Guiding Principles assign states the primary duty to protect against corporate human rights abuses, they also urge companies to undertake a regular process of “human rights due diligence” whereby human rights abuses are treated as core business risks.

The Guiding Principles define the general parameters of human rights due diligence, which is aimed at identifying, preventing, mitigating, and accounting for potential adverse human rights impacts.Footnote 6 Companies are expected to “seek to prevent or mitigate adverse human rights impacts that are directly linked to their operations, products or services by their business relationships, even if they have not contributed to those impacts.”Footnote 7 Business relationships are understood to include relationships with “entities in [a company’s] value chain.”Footnote 8 Thus, human rights due diligence requires a company to map its supply chain in order to identify potential human rights risks among its suppliers. The Guiding Principles outline a four-step framework for conducting due diligence: “assessing actual and potential human rights impacts, integrating and acting upon the findings, tracking responses, and communicating how impacts are addressed.”Footnote 9 The process of conducting due diligence should be ongoing throughout the life of an activity, include all internationally recognized human rights as a reference point, and extend to a company’s suppliers.Footnote 10 The Guiding Principles further call on states to encourage, or, where appropriate, require, reporting by companies of their due diligence measures to prevent adverse human rights impacts.Footnote 11 The approach to due diligence of the Guiding Principles was subsequently incorporated by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in its revised Guidelines on Multinational Enterprises.Footnote 12

Since 2011, the voluntary standard of human rights due diligence has transformed into a legislative mandate. Early legislation, including modern slavery laws in California in 2010, the United Kingdom in 2015, and Australia in 2018, exclusively focused on reporting by mandating corporate disclosure of efforts (if any) to conduct supply chain due diligence related to modern slavery risks.Footnote 13 There has also been a movement among EU countries to require companies to conduct human rights due diligence—see, for example, the French 2017 Duty of Vigilance Law, the Dutch 2019 Child Labor Due Diligence Act, the German 20x21 Supply Chain Due Diligence Act, Norway’s 2021 Transparency Act, and a Swiss 2022 ordinance on human rights due diligence.Footnote 14 Moreover, the European Commission (2022) recently adopted a proposal addressing human rights and environmental due diligence—namely, the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive. The proposed rules would require large EU companies, and some non-European companies doing significant business in Europe, to assess their actual and potential human rights and environmental impacts throughout their operations and down their supply chains and to take action to prevent, mitigate, and remedy identified human rights and environmental harms. While existing laws contain limited oversight and enforcement features, the incorporation of human rights due diligence into hard law represents a significant development in the evolution of this legal norm (Martin Reference Martin, Deva and Birchall2020; Chambers and Vastardis Reference Chambers and Yilmaz Vastardis2021).

But what does human rights due diligence look like in practice and how should it be interpreted in various contexts? Scholars, activists, and corporate managers have debated this question as they struggle to operationalize this critical, but vaguely defined, legal norm. Given that human rights due diligence features “ambiguous and imprecise language” and extensive scope for interpretation, it is prone to “cosmetic compliance” and is open to corporate discretion (Landau Reference Landau2019, 15–16). According to the Corporate Human Rights Benchmark, based on an analysis of disclosures from 229 global companies, human rights due diligence is a key challenge for companies. It “remains an area of poor performance across all sectors” and the lowest area of improvement in the four years since the launch of the annual benchmarking report. In fact, almost half of the companies assessed (46.2 percent) failed to score any points under the benchmark’s human rights due diligence indicators (Corporate Human Rights Benchmark and World Benchmarking Alliance 2020). While this inconsistent performance is due in part to a lack of willingness among companies to take human rights seriously, another important factor is the absence of guidance on what constitutes adequate human rights due diligence and which tools companies can use to achieve this standard. The area that has provided the most lessons for how to interpret the norm of human rights due diligence is the implementation of mineral supply chain regulations.

THE REGULATION OF GLOBAL MINERAL SUPPLY CHAINS

While the meaning of human rights due diligence continues to evolve with the expansion of regulation and growing corporate awareness, the context where this norm is becoming most clearly defined is in the responsible sourcing of global mineral supply chains. The conflict minerals regime is “one of the most advanced and complex fields of regulation on corporate respect for human rights” (Ooms Reference Ooms2022, 49). International standards and binding legislation in this area have solidified human rights due diligence as the global standard for regulating corporate activity with respect to human rights. However, a close analysis of these laws reveals that gaps remain as to how this norm is interpreted in practice, particularly regarding the human rights risk assessment process. As we will discuss in the next section, the RMI has attempted to fill this vacuum by providing critical guidance on how to identify and assess risks in global supply chains.

The most comprehensive legal document that defines human rights due diligence in the context of global mineral supply chains is the OECD’s 2011 Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas (OECD Guidance).Footnote 15 The OECD Guidance provides a framework for conducting due diligence as part of the responsible sourcing of minerals. It defines due diligence as “an on-going, proactive and reactive process through which companies can ensure that they respect human rights and do not contribute to conflict.”Footnote 16 According to the OECD’s standard, companies should follow five steps when conducting due diligence: (1) establish strong management systems; (2) identify and assess risk through supply chain mapping; (3) design and implement a strategy to respond to identified risks; (4) conduct an independent audit of supply chain due diligence; and (5) report annually on supply chain due diligence. The framework has been embraced by corporate actors as it provides more details than the UN Guiding Principles’ four-step approach. Yet, while the OECD Guidance articulates the steps involved in conducting human rights due diligence, companies have faced challenges in implementing these steps. According to the OECD (2013), companies exhibited “a lack of risk management strategies” and “inadequate audit and reporting processes” in the early years of implementation (Cullen Reference Cullen2016, 773).

While the OECD Guidance is not legally binding, it has been referenced in mandatory conflict minerals legislation passed in the United States (section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank Act) and EU (EU Regulation 2017/821). Section 1502 of the US Dodd-Frank Act was the first regulation to create binding rules on human rights-related supply chain due diligence. The law imposed a new reporting requirement on publicly traded companies that manufacture products using minerals that are potential sources of funding for militias (that is, conflict minerals). The stated rationale behind the law was that, by curbing the illegitimate exploitation of natural resources by state and non-state armed groups, it would indirectly hinder financing of the ongoing conflicts in the eastern DRC. Under section 1502, companies must provide a specialized disclosure form to the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) on whether the sourcing of conflict minerals originated in the DRC and bordering countries. If so, the companies must submit a conflict minerals report describing the due diligence measures taken to assess whether those conflict minerals directly or indirectly financed or benefited armed groups in the covered countries. The quality of the due diligence must meet nationally or internationally recognized standards, such as the OECD Guidance.

Throughout the development and initial application of section 1502, companies voiced concerns over the lack of clarity in the conflict minerals legislation as well as the absence of tools for implementing due diligence (US Government Accountability Office 2013, 13). The chain of custody requirement under section 1502 is exceedingly difficult to comply with because of the length and complexity of many global supply chains, where a purchaser may not have adequate leverage to force a supplier to disclose material content. The SEC did not provide any guidance as to what due diligence entails or how to carry out the risk assessment process. While the law recommends the use of the OECD Guidance, the standard was relatively new when the law was passed and, thus, untested. Its use of broad terms such as “reasonable efforts” were undefined and lacked quantitative tools for measurement (Hofmann, Schleper, and Blome Reference Hofmann, Schleper and Blome2018, 129), which resulted in “confusion” among companies struggling to comply with the recommended OECD Guidance (Schwartz Reference Schwartz2016, 165). Furthermore, companies were uncertain about the auditing process, including its scope (for example, whether the audit covers only a company’s conflict minerals report or the entire supply chain due diligence process), who would be qualified to conduct such an audit, and what information needs to be included in the certification process.Footnote 17

In 2017, the EU followed in the steps of the United States in passing its own legislation on the responsible sourcing of minerals from conflict-affected and high-risk areas.Footnote 18 EU Regulation 2017/821, which went into effect in 2021 and is estimated to apply to over 800,000 European companies, requires select EU importers of tin, tantalum, tungsten, and gold to disclose the steps they have taken to address risks in their supply chains (The Guardian 2015). In addition, the law requires mandatory, independent third-party audits for smelters and refiners. While the EU regulation has a broader geographic scope than section 1502 (as it applies to conflict minerals sourced in all conflict-affected or high-risk areas, not just in the DRC region), it was inspired by the US legislation and similarly draws on the due diligence framework set out in the OECD Guidance.

The implementation of transnational legal requirements on conflict minerals, such as those found in the US and EU laws, is complex given that supply chains can span multiple jurisdictions and thousands of suppliers that may be difficult to identify. Due diligence typically involves a company assessing actual or potential risks associated with its activities and relationships and then taking steps to mitigate those risks. While firms already conduct this process on various business activities, applying it to multi-tiered supply chains presents unique challenges. Since companies often rely on first-tier suppliers to identify and audit those in the second tier, which in turn identify and audit the next tier and so on, comprehensive monitoring by companies is difficult (US Government Accountability Office 2013).

The challenge for the US and EU conflict minerals legislation, and, in fact, for all existing and future transnational supply chain-related regulations, has been how to implement human rights due diligence on suppliers operating abroad, especially given the complex, multi-tiered, and fluid nature of supply chains. Laws on responsible minerals sourcing have suffered from a lack of clarity as to their requirements and an absence of supporting tools for implementation. In the face of little guidance from governments on human rights due diligence procedures, companies have struggled with how to identify and assess risks in their supply chains. As companies demanded tools to assist them in complying with the laws, the RMI has stepped in to fill this need. As a multi-industry association with the requisite expertise and resources, the RMI has been able to facilitate corporate collaboration, coordinate sourcing initiatives and standards, and, most importantly, offer guidance on how to implement existing conflict minerals regulations and interpret the norm of human rights due diligence in mineral supply chains.

THE ROLE OF INDUSTRY IN INTERPRETING HUMAN RIGHTS DUE DILIGENCE

The role of the RMI in the regulation of mineral supply chains represents the importance of industry in implementing existing legislation and interpreting the norm of human rights due diligence. The RMI has been instrumental in designing tools for the critical step of human rights risk assessment, which is the most challenging component for business within the broader due diligence process. According to a benchmarking report of human rights disclosures by Shift (2017), a leading non-profit center for business and human rights practice, “approximately 90% of the companies [did] not have a coherent narrative about how risk or impact assessments inform mitigation actions taken, how decisions are made or if senior management is ever involved.” Information disclosed was largely limited to companies’ commitments and policies in addressing human rights, but not the concrete steps for assessing and managing human rights risks (Chambers and Vastardis Reference Chambers and Yilmaz Vastardis2021, 347). The RMI’s risk assessment tools have provided companies with important guidance on how to carry out and report on human rights due diligence. Yet, as we explain below, these technocratic tools are based on shallow categories and undifferentiated rankings with no independent verification of corporate-disclosed information. In order to understand the role of the RMI in interpreting the norm of human rights due diligence, we first provide an overview of the organization and then analyze the risk assessment tools that constitute the backbone of corporate compliance with conflict minerals legislation.

The Responsible Minerals Initiative

As a multi-industry association, the RMI is made up of member companies from multiple industries including electronics, automotive, aerospace, jewelry, and communications. The RMI is an initiative of the Responsible Business Association (formerly known as the Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition), a non-profit organization and the largest multi-industry body focused on responsible minerals supply chains and corporate social responsibility. The RMI’s original mandate was to support responsible sourcing around the use of conflict minerals as a funding mechanism by militias and the national army in the DRC (Eichstaedt Reference Eichstaedt2011; Hanai Reference Hanai2021). Since 2016, increased public attention to the sourcing of other minerals, including cobalt, has led to a reorientation of the RMI to address broader environmental, social, and governance concerns outside the conflict minerals sphere.Footnote 19

As of March 2023, the RMI’s membership includes over four hundred companies, mostly representing the downstream and, to a lesser extent, midstream sectors. Since the RMI broadened the scope of its mandate to include all minerals, many upstream mining companies have joined the organization as well. Member contributions are based on companies’ annual revenue.Footnote 20 The RMI also hires auditors to perform assurance, with an average audit fee of fifty-eight hundred dollars.Footnote 21 The financial structure of the RMI’s membership enables the internal functioning of the organization and the management of its due diligence system for responsible sourcing.

In light of its expanding mission, the RMI has emerged as a dominant market player in responsible minerals sourcing. The organization’s success is largely based on the development of the Responsible Minerals Assurance Process (RMAP), which is one of the most prominent standards in the field of responsible minerals sourcing and an internationally recognized framework for the implementation of section 1502 and EU Regulation 2017/821. According to a company representative, compliance with the RMAP is “a decision factor for [determining whether to] use and prioritize smelters and refiners.”Footnote 22 The RMAP employs independent third-party assessments for smelters and refiners according to industry standards for responsible sourcing practices and management systems. Companies apply RMAP protocols to report on their level of due diligence (in accordance with the OECD Guidance) and to make a determination on whether their refiners and smelters are sourcing conflict minerals.

The targeted intervention of the RMAP centers on smelters and refiners, which are considered the “pinch point” of the supply chain after which identification of the minerals’ origin is nearly impossible. According to a RMI Governance Committee member, smelters are central to the RMI’s assurance process: “Since 2007, when [the RMI] first started talking about what the supply chain looked like, it became apparent that the smelters and refiners were a bottleneck. They were a choke point in the supply chain, and therefore, they provided an opportunity to intervene. They provided a point of intervention.”Footnote 23 Smelters under the scope of the RMAP are categorized by their level of engagement, with active smelters referring to those committed to undergoing an audit and conformant smelters referring to those that have successfully passed the audit. The RMI maintains a list of about 220 conformant smelters across five minerals, which illustrates its dominance in the sector and the appeal of its assurance protocol (RMI 2023). The RMI has also developed a Grievance Mechanism to raise concerns about its protocols, including smelting and refining operations that fall within the scope of the RMAP.Footnote 24

The RMI plays a key role in facilitating the implementation of US and EU conflict minerals legislation through the RMAP and related tools. The organization evolved to fill a vacuum left by the US government in 2010 when it passed conflict minerals legislation but failed to provide sufficient guidance on how to implement its due diligence requirements. The lack of guidance prompted the industry association to define its own sourcing requirements, reporting template, and auditing system in order to assist members in complying with the new law. The RMI’s assurance program, the RMAP, responded to an identified need among companies to tackle on-the-ground sourcing risks in the DRC through human rights due diligence. Corporate members and consultants have affirmed the RMI’s central role in implementing section 1502:

[The RMI] was a driver for the industry to really address the conflict minerals…. [It] play[s] a very important role in the facilitation, [not only] establishing the standard and expectations, but actually, administering the program…. I think part of [its] success lies in [its] resources such as the technical advisors, trainings, webinars, [and] in-person trainings, … to help empower and enable the smelters and refiners, to actually accomplish what we’re asking [it] to accomplish.Footnote 25

The RMI has provided really great resources and tools to organizations that are trying to … comply with U.S. regulations…. It’s been a really incredible resource for us. And when I joined [my company], we were in a position of really starting our program from scratch, from the beginning, and really relied heavily on the RMI tools and resources to build our program in a way that’s aligned with the industry and the expectations not only of our customers but also now many of our suppliers as well.Footnote 26

As of 2023 the RMI’s protocols covering conflict minerals constitute the most comprehensive in place for the four minerals covered under section 1502. As the only conflict minerals-focused and OECD-aligned due diligence audit system, the RMAP constitutes the de facto assurance mechanism for companies to meet their obligations under section 1502 as well as EU Regulation 2017/821.

In January 2021, when EU Regulation 2017/821 came into effect, companies faced the same challenge of how to implement its due diligence mandate. In response, the European Commission established the Due Diligence Ready! online portal, which recommends existing tools, including the RMI’s RMAP, to support companies in complying with the regulation’s requirements.Footnote 27 Among the RMI’s tools that are cited by the European Commission (2021) are the Conflict Minerals Reporting Template (a free, standardized self-reporting survey tool that supports corporate identification of mineral suppliers’ due diligence performance and practices); the Grievance Mechanism, which has been previously mentioned; the Global Risk Map (a tool for companies to identify and compare governance, human rights, and conflict risk indices across geographic regions globally); and the RRA, which is a self-assessment tool for minerals and metals producers and processors to assess and report on their social and environmental risk management practices and performance).

Inclusion of the RMI’s tools in the European Commission’s Due Diligence Ready! platform is a clear recognition of the industry association’s market dominance in this area. Since 2017 when the EU passed its conflict minerals regulation, the RMI began taking steps to position itself as the preferred provider of resources and tools for the law’s implementation. It first underwent “alignment assessment” by the OECD, which is the process by which the OECD evaluates the alignment of an industry, government, or multi-stakeholder initiative with its due diligence guidance. In 2019, the RMI applied to the European Commission for recognition of its RMAP and related tools to help companies meet their due diligence obligations under the regulation (Responsible Business Alliance 2020a, 1). Finally, in 2020, the industry association opened its first European office in Brussels as the European Commission was preparing to implement its new conflict minerals regulation beginning in January 2021.Footnote 28

In this article, we center our analysis on the RMI’s risk assessment tools for companies. According to an independent expert that works with the RMI, “[t]he RMI has become the de facto standard for [a] company’s risk assessment…. What the RMI does in many ways, in my view, is help provide that risk-assessment data collection for the companies disclosing under section 1502…. I think the RMI information is a critical part of any company’s actual due diligence process.”Footnote 29 As the first step of the due diligence process, risk assessment allows companies to identify weaknesses in their operations as well as to pinpoint suppliers unaligned with industry best practices. The RMI’s risk assessment toolkit is core to the due diligence process mandated by US and EU conflict minerals legislation and defines the scope and level of audit assessment required from a smelter or a refiner. In the next section, we focus on the RMI’s RRA, which constitutes a key tool for companies implementing human rights due diligence in mineral supply chains.

The RMI’s Risk Assessment Tools

The RMI’s RRA is an online self-assessment and due diligence tool for companies to identify and assess environmental, social, and governance risks across fifteen minerals and metals in raw materials supply chains. The RRA was initially developed by Apple Incorporated and then adapted by the RMI for integration into the RMAP through a cloud-based platform available to member companies. Jennifer Peyser, vice president of responsible sourcing at the RMI, identifies the RRA as “pivotal to enable risk monitoring in mineral supply chains.”Footnote 30 Users have also described it as a critical tool to facilitate company due diligence for their often-complex material supply chains: “The prime motivation … for using the RRA as a risk assessment and communication tool is to respond to the expectations to implement supply chain due diligence, the extent and scope of which is anticipated to expand. The RRA is seen as having the potential to help companies fulfill expectations for responsible sourcing with an extended reach up the supply chain, while softening the cost burden of compliance” (RMI 2019, 16). The RRA is now part of industry best practice and is utilized by 366 downstream companies and upstream smelters and refiners as of the end of 2021 (Apple 2021). It is designed to address the challenges faced by downstream companies to appropriately manage risks given the size and complexity of their global supply chains.

The RRA is comprised of thirty-two issue areas across a variety of social and environmental risks. Those areas that are most directly related to human rights include legal compliance, business relationships, child labor, forced labor, freedom of association and collective bargaining, discrimination, gender equality, working hours, occupational health and safety, community health and safety, artisanal and small-scale mining, human rights, security and human rights, Indigenous peoples’ rights, cultural heritage, and due diligence in mineral supply chains. Other related areas include business integrity, stakeholder engagement, community development, land acquisition and resettlement, and transparency and disclosure (Copper Mark and RMI 2020).

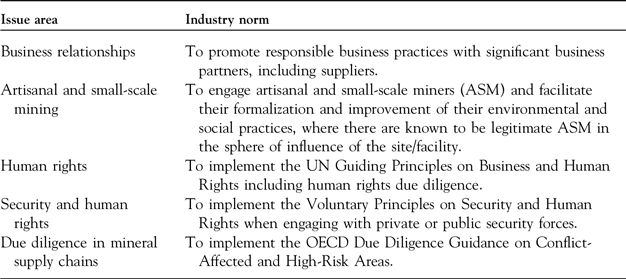

In order to understand how the RRA contributes to the interpretation of human rights due diligence, it is useful to analyze the criteria and methodology behind its indicators. Among the above issue areas directly related to human rights, there are five whose description specifically cites “due diligence”: business relationships, artisanal and small-scale mining, human rights, security and human rights, and due diligence in mineral supply chains. The RRA dashboard includes indicators under each issue area that correspond to a set of benchmarked “industry norms.” These industry norms, which are derived from a comparison of over fifty commonly used voluntary sustainability standards (RMI 2021b), constitute “good management practice” according to “the requirement that is most used by most of the standards analyzed” (RMI 2021a). Based on a review of the relevant documents for each issue area (for example, codes, provisions, protocols, guidance, and manuals), the RRA aims to distill the referenced standards into a simplified statement. These statements are in turn converted into a set of three (and, in some cases, five) options or check boxes that companies select, as described in more detail below.

For instance, Table 1 includes the industry norms for the five issue areas citing due diligence.

Table 1. RRA’s industry norms for the five issue areas citing due diligence

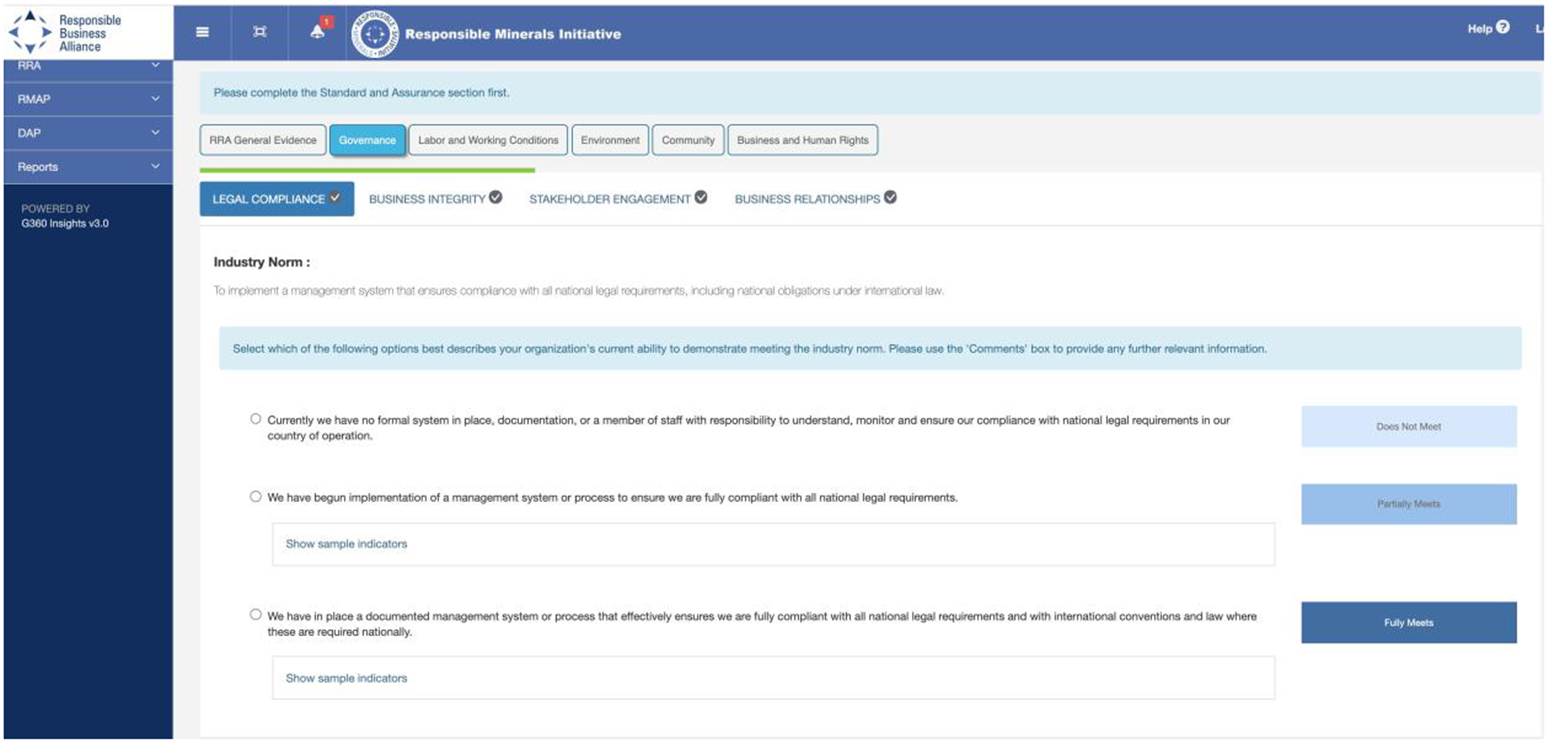

For each industry norm, the RRA asks companies to make the following ranking: “does not meet,” “partially meets,” or “fully meets” (Copper Mark and RMI 2020). Under some issue areas, the RRA includes two additional categories for ranking: “exceeds” and “not applicable.” Figure 1 provides a snapshot of the RRA’s dashboard (Copper Mark and RMI 2021, 5). While companies are invited to provide optional additional information in a “Comments” box, the dashboard only requires that companies check the appropriate box under each category.Footnote 31

Figure 1. Snapshot of the RRA’s dashboard.

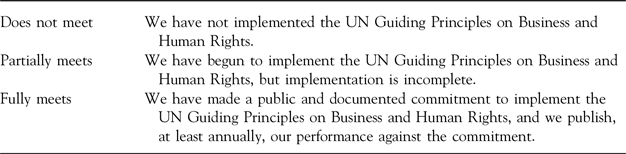

Yet, while the RRA’s industry norms represent succinct summaries of the existing standards covering each issue area, they provide only broad guidance as to the expected practice. It is striking how little differentiates between some of the categories under certain issue areas and how broadly the areas are defined. This is a concern that is affirmed by the companies themselves. According to interviews with RRA platform users, “[s]ome RRA questions are general and are perceived as being too vague to give accurate responses” (RMI 2019, 18). In addition, the evidence that companies are required to provide is quite weak and reliant exclusively on companies’ own documentation. Take, for instance, the human rights issue area. The RRA tool includes the three categories for ranking along with descriptive statements under each category, as indicated in Table 2 (RMI 2020).

Table 2. Rankings under the RRA’s human rights issue area

There is not a substantial difference between the criteria for “partially meets” and “fully meets,” and only a slight difference between “does not meet” and “partially meets.” Based on this methodology, a company can declare that it “fully meets” the human rights indicator by simply making “a public and documented commitment to implement the UN Guiding Principles” but not necessarily implementing them. Despite the low standard set by the “fully meets” criterion, most companies are nonetheless failing to meet this bar. According to a RMI analysis of self-assessed user performance of RRA-user companies, the lowest performance reported was for the human rights risk area: “In 2017, 62 percent of the RRA users said they ‘do not meet’ or ‘partially meet’ the expectations for this area” (RMI 2019, 14). In addition, the criteria of implementing, or beginning to implement, the UN Guiding Principles is a shallow and insignificant indicator on its own given that the principles themselves do not contain substantive standards that are specific to corporations.Footnote 32 Furthermore, the assessment for human rights, as well as for the other indicators, is exclusively based on companies’ own evaluation of the evidence that they themselves provide. What is particularly notable is that the documentation to support companies’ risk assessments does not have to be independently verified. It is simply uploaded by companies, which makes them the arbiter of what constitutes human rights due diligence and whether the process has been carried out sufficiently. While the guidance is generally useful in providing companies with helpful information to assess each risk, the absence of independent verification of company evidence or their risk evaluation means that there is a lack of accountability to external stakeholders, which is one of the objectives of human rights due diligence under the UN Guiding Principles. In fact, users themselves have expressed the view that adding independent verification to the RRA “would deepen its credibility” (RMI 2019, 16).

The RMI regularly reviews the RRA in order to keep the identification of risks, industry norms, and voluntary standards up to date and representative of the challenges facing mineral supply chains. Since the RRA is benchmarked according to fifty-six voluntary sustainability standards frequently used in the mining and mineral industry, it is a constantly evolving tool updated to reflect changes to these standards (RMI 2018). The issue areas are also expected to change over time as company priorities shift and different risks emerge (RMI 2021a).

In addition to the RRA and its indicators being originally developed by Apple, and then adopted by the RMI, the process of reviewing and revising the risk assessment tool is also largely in the hands of the industry association and its member companies with a limited amount of public consultation and stakeholder involvement. The RRA review process is overseen by RMI staff and run by a Technical Committee, which is composed of technical experts in standards development, auditing, and mineral supply chains. Although the Technical Committee includes companies as well as non-industry representatives, the RMI acknowledges that several main stakeholder groups—for example, representatives of workers, local communities, and Indigenous peoples—are not, or insufficiently, represented on the committee (Copper Mark and RMI 2022a, 2).

While primarily carried out by the Technical Committee, the RRA review process also receives support from several RMI working groups composed of member companies—including the RMI Steering Committee, the RMI Standards Advisory Group, and the RMI Mining Engagement Team. The RMI staff consults with these working groups on “the number and range of the RRA’s ‘issue areas,’ the technical content of the RRA’s industry ‘norms,’ the review of [Voluntary Sustainability Standard Systems] included in the Standards Comparison, the updating of the RRA and its methodology, and the scope and timing of public consultations” (RMI 2021b, 2). For instance, the Standards Advisory Group, a multi-stakeholder group of subject matter experts, provides technical guidance on the development of new indicators. Technical support is further provided by an external sustainability advisory firm called TDI Sustainability (formerly, The Dragonfly Initiative [TDI]), which is composed of business and risk management experts (Copper Mark and RMI 2021, 18). While external stakeholders can provide feedback through periodic public consultations and stakeholder workshops,Footnote 33 comments are then reviewed by the Standards Advisory Group, and recommendations are transferred by the RMI staff to the RMI Steering Committee for approval (RMI 2018). The RMI Steering Committee has the ultimate decision-making authority over any changes to the RRA.

Companies’ reliance on the RRA to conduct human rights due diligence is not well publicized, as demonstrated by the limited reporting of the RRA in corporate statements. While over 360 downstream companies and upstream smelters and refiners rely on the RRA, they rarely report on their use of the tool (Apple 2021). Only a small number of companies, including Ford, Apple, Intel, and Tesla, mentioned the tool in their recent special disclosure forms and conflict minerals reports submitted to the SEC under section 1502 of the Dodd-Frank Act. Hence, corporate reporting on the use of the RRA is minimal and mostly confined to financial disclosures. The few companies that have reported on the RRA only made a brief reference to the tool and did not disclose any details of their assessments, including their performance under the indicators for each issue area.

The example of the RRA’s online platform thus illustrates how companies are in fact regulating themselves through tools developed by the industry association. Companies largely control the design, management, and revision of the RRA, which is a critical tool to facilitate the implementation of recent conflict minerals legislation. The RRA relies on companies’ own evidence that is not independently verified as well as their own determination of supply chain risk based on general and sometimes vague categories and rankings that lack substantial differentiation. Thus, the technocratic nature of the RRA masks the corporate interests that are controlling how human rights due diligence is being interpreted and implemented on the ground.

SUPPLY CHAIN GOVERNANCE AT A DISTANCE

While the goal of human rights due diligence is to inform the public of a company’s human rights performance and thereby enhance corporate accountability toward external stakeholders, its application in practice is achieving the opposite aim (Mares Reference Mares2018). The case of the RMI illustrates how a multi-industry association and its corporate members are exercising considerable control over the interpretation and implementation of human rights due diligence. Even when the substantive human rights performance of companies may be poor, it is hidden behind technocratic tools and the discourse of risk management. Experts are conducting supply chain mapping and risk assessments by applying auditing tools and other management techniques developed by the RMI. Through these technical practices, experts are transforming the norm of human rights due diligence from an instrument of corporate accountability to a tool of corporate legitimacy.

Supply chain governance rests on the ability of a company to build relationships with its direct and far-removed suppliers. By creating this “attachment” with the actors in their value chains, companies can establish relations of accountability. This connection has been part of the core rhetoric of corporate social responsibility and a guiding principle through which human rights due diligence is implemented. Yet we argue that companies are perpetuating a narrative of attachment while, in fact, fostering an ethic of detachment that maintains a distance between their sourcing practices and their suppliers. This ethic of detachment rests on a technocratic assemblage of tools that structure the engagement of companies with their suppliers around strictly delineated limits and endpoints, thereby allowing corporate executives and managers “to separate themselves legally, morally, and socially from binding obligations and responsibilities to producers” (Cross Reference Cross2011, 35). These tools, or technologies of detachment, enable corporations to manage, control, and limit their attachments to suppliers and hence deflect accountability (35).

Thus, while the RMI’s technocratic tools have facilitated corporate compliance with conflict minerals legislation, they are enabling global supply chains to be “governed at a distance” (Rose and Miller Reference Rose and Miller1992). In other words, governments are outsourcing the power to regulate supply chains to industry associations and their corporate members who exercise control through technologies of governance (Davis, Kingsbury, and Merry Reference Davis, Kingsbury and Engle Merry2012). The RMI’s tools reinforce “techno-managerial patterns within top-down governance structures [that] leave limited space for ‘non-expert’ knowledge” (Diep et al. Reference Diep, Priti Parikh, Alencar and Rodolfo Scarati Martins2022). For instance, the RMI’s RRA is based on industry norms primarily defined by experts with limited opportunities for public engagement.

Corporate-controlled human rights due diligence builds on a technocratic model of governance that is facilitated by an industry association (Shore and Wright Reference Shore and Wright2015). In our case study, the RMI has developed a set of risk assessment and auditing tools that maintain a distance between global corporations and their suppliers. The RRA’s simplification of complex issues (through a threefold approach of “does not meet,” “partially meets,” and “fully meets” and supported by company-provided evidence) represents a technocratic response to supply chain regulations that places the due diligence determination in the hands of corporations. This suggests that, while recent disclosure laws may appear to be invoking state authority over supply chain governance, they are in fact masking the power being wielded by companies themselves in regulating their own supply chains. In other words, corporations are in effect regulating themselves under the guise of state regulation.

While the regulatory landscape around business and human rights has recently evolved toward mandatory disclosure regimes, industry associations such as the RMI are playing a significant role in the implementation of legislative requirements and the interpretation of international legal norms. Their technocratic auditing tools imitate the effects of governmental regulations while echoing private sector interests and needs. This is an example of instrumental anti-politics that “aim at placing technocratic experts on the throne of politics” and substituting the political interests of corporations over the public (Schedler Reference Schedler1997, 12). Tools such as the RMI’s RRA attempt to imbue a technocratic rationality into decision making and, by doing so, render domains (however complex, such as mineral supply chains) calculable and susceptible to evaluation and intervention. A guise of neutrality and objectivity exists behind these tools and masks underlying power relations. Their effectiveness depends on experts with specialized skills and esoteric knowledge—“[e]xperts hold out the hope that problems of regulation can remove themselves from the disputed terrain of politics and relocate onto the tranquil yet seductive territory of truth” (Miller and Rose Reference Miller and Rose2008, 69).

Moreover, there is a detachment between tools such as the RRA and the normative goals of supply chain regulations that aim to provide transparency and accountability in the sourcing of conflict minerals. While section 1502 is aimed at improving the livelihoods of Congolese individuals impacted by the sourcing of conflict minerals, legislative requirements are translated into far-removed indicators, completely divorced from on-the-ground realities. According to a NGO representative, “something [the RMI] could do a lot more of, is working to engage not just Congolese voices, but voices from stakeholders and mining communities, and other conflict affected and high-risk areas.”Footnote 34 While supply chain legislation relies on public scrutiny to promote more responsible sourcing and envisions the public as the intended audience for due diligence reports, technocratic tools for implementing these laws serve to keep suppliers at a distance and turn the public into a “passive audience” (Ooms Reference Ooms2022, 51, 57). Thus, supply chain governance at a distance fosters corporate legitimacy rather than corporate accountability.

CONCLUSION

This article has examined the role of industry in implementing and interpreting the international legal norm of human rights due diligence. Our study has focused on the RMI, which has assumed a leading role in implementing supply chain legislation and interpreting the norm of human rights due diligence in mineral supply chains. We have demonstrated that, while the RMI’s technocratic tools are facilitating corporate compliance with existing regulations, they are also masking the underlying corporate interests that control how human rights due diligence is being interpreted and implemented on the ground. These technical practices illustrate how global supply chains are being governed at a distance whereby companies divest themselves of responsibility to their suppliers.

The objective of human rights due diligence is to create transparent and responsible supply chains in order to enhance corporate accountability. As more jurisdictions require companies to conduct human rights due diligence (rather than just legislating that they report on corporate due diligence efforts, if any), transnational businesses are increasingly coming under pressure to adopt effective mechanisms to uncover abuses in their supply chains. Yet rather than establishing relationships of accountability between corporations and their suppliers as well as corporations and the public, supply chain governance at a distance fosters an ethic of detachment that stands in contrast to the goals of human rights due diligence. In the case of the RMI, corporate interests are controlling how supply chain legislation is being implemented through the design and management of technocratic tools.

There are important accountability implications associated with industry associations such as the RMI playing such a central role in the implementation of transnational laws and, in particular, in the interpretation of international legal norms. The RMI is serving as a regulatory authority in the absence of clear guidance from national legislators. Yet the legitimacy of the RMI in this governance role is questionable given its lack of public accountability, an absence of oversight mechanisms, and the fact that it is controlled by particular business interests. As an initiative of the Responsible Business Association, the RMI has a stated aim of “contributing positively to social economic development globally.” It does not conduct any lobbying activities but, rather, has a stated mission “to support responsible mineral sourcing broadly and convene … stakeholders to continually shape dialogue and practices.”Footnote 35 Since the RMI is a non-profit organization that focuses on activities that benefit society, it carries a greater responsibility to the public and should be held to higher standards of transparency. Yet the RMI is largely invisible to regulatory oversight, thus resulting in little opportunity for public deliberation over the construction and application of its tools and an absence of external verification of corporate assessments.

Our analysis of the RMI’s risk assessment tools reveals a box-ticking approach to human rights due diligence based on imprecise indicators and unreliable information. The ranking categories are vague, lack significant differentiation, and are based on companies’ own evidence and determination of supply chain risk. Without independent verification, stakeholders cannot trust the data behind the indicators or the reliability of due diligence reports. We argue that effective measures of human rights due diligence need to incorporate precise and meaningful indicators and require third-party verification of disclosed information and corporate risk assessment. Possible third parties include NGOs or auditing firms as long as they are not directly involved in the production or governance of the tools. Furthermore, assurance providers should follow standardized and transparent criteria and procedures that are publicly disclosed. States should regulate the third-party assurance providers through certification or accreditation or delegate oversight to an independent entity.

It is also critical that governments provide more specific guidance on the implementation of supply chain laws and the interpretation of norms such as human rights due diligence rather than outsourcing these regulatory functions to unaccountable private actors. While the RMI has made efforts to organize public consultations, corporate interests continue to exert considerable influence over decision making. States should more actively regulate how companies implement and report on their human rights due diligence processes. In particular, they should require third-party verification of due diligence reports according to a uniform standard and require companies to be more transparent as to how they performed on reporting metrics. Instead of exclusively relying on tools developed by the RMI, government agencies should expand participation by the public and NGOs in the design of indicators and other assessment tools. Finally, they should ensure that metrics measure how companies are applying (and not just adopting) human rights policies and how they are implementing due diligence processes. In doing so, they should respond to stakeholder concerns, especially those of groups that are insufficiently represented in the RMI’s governance structure and revision process (for example, workers, labor unions, local communities, and Indigenous peoples).

Our analysis suggests potential directions for future research. Considering the EU’s proposed Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive, a large number of companies operating in the EU may soon be required to identify and, where necessary, prevent, end, or mitigate adverse impacts of their activities on human rights and the environment. As human rights due diligence becomes a legislative mandate in more countries, companies will seek guidance from a variety of third parties including not just industry associations but also other corporate actors such as consulting firms, accounting firms, information technology firms, and platform businesses. Future scholarship should examine how these actors use technologies of governance to implement new global supply chain regulations, including how they influence the interpretation of human rights due diligence and its application in practice. Such empirical studies can shed further light on the technical practices by which corporations shape international law and the transnational lawmaking process.