INTRODUCTION

Overrepresentation of ethnic and racial groups in prisons—especially when the groups in question are disproportionately poor and historically marginalized—is a concerning issue; it suggests the possibility of widespread bias in law enforcement and/or a pattern of socioeconomic exclusion that contributes to increased risks of criminal involvement and contact with police. Whether disproportion is the consequence of bias, inequality, or something else, it represents both a threat to the legitimacy of criminal justice institutions and the more troubling prospect that a country’s criminal justice outcomes are less than fair. Thus, ethnic and racial overrepresentation in prisons has long been a subject of scholarly concern (Piquero Reference Piquero2008).

Study of the United States—and its uniquely punitive features—has tended to dominate the discussion of prison disproportionalities, yet prior research shows comparable extents of disproportion occurring in several countries and under varied punitive conditions (Tonry Reference Tonry1997). Indeed, it is now practically a criminological truism that “everywhere, the most marginalized groups of society are overrepresented in prisons” (Karstedt Reference Karstedt2021, 5). However, cross-national research observing and measuring this overrepresentation remains scarce. Not only is this a noticeable gap in the literature, but the fact that prison disproportion occurs in various and varied places suggests an opportunity for cross-national analysis to uncover patterns that single-country analysis may be prone to overlook.

Ethnoracial prison disproportion has proven difficult to study in a cross-national context primarily due to the variety of ways in which societies and governments define ethnic and racial difference and differences in the extent to which national statistics include data on prisoners’ ethnic and racial identities. A lack of data remains a significant barrier to the multinational study of prison demographics. Nonetheless, the heterogeneity of ethnoracial categorizations across countries—which has limited prior cross-national research to countries that share arguably comparable census categories—can be overcome. This article employs a method that extends the analysis of prison demographics across countries with differing census categories and that systematically addresses several understudied inquiries: what is the extent of ethnic, racial, and indigenous disproportion beyond what limited prior research has uncovered? How do these national prison populations compare to each other in terms of demographic proportionality? Finally, what can be done to explain any cross-national patterns of disproportion observed? For example, can national conditions—as defined by socioeconomic and criminal justice factors—clarify why prison populations in some countries are more disproportionate than in others?

These inquiries are addressed using a novel data set covering eighteen democracies across six continents,Footnote 1 compiled from publicly available and Internet-searchable prison and national census data targeting the year 2016.Footnote 2 DemocraciesFootnote 3 were chosen as the regime type for this study due to the democratic aspirations of nondiscrimination, equality under law, impartial law enforcement, and the tendency of democratic societies to collect statistical data related to the rights of minority groups. That is, democracies are places where further understandings of prison disproportion are more likely regarded as useful. Though many democracies do not make racial and ethnic demographic data on prisoners publicly available, the data set covers a wide range of democracies in terms of social, economic, and criminal justice characteristics, which allows for potentially more insightful comparisons.

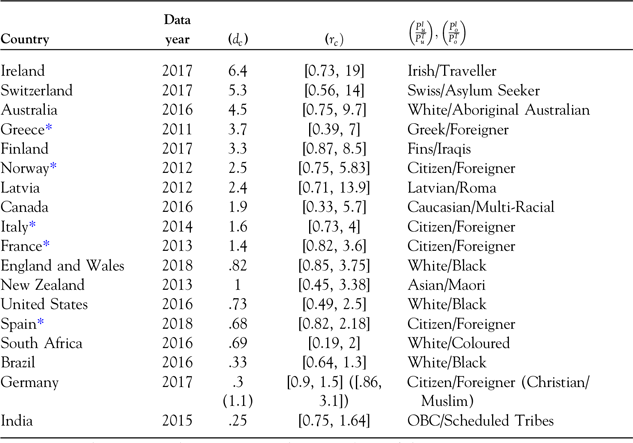

This data is analyzed using a modification of the Ortona Index, which has been used previously to analyze disproportion in proportional representation systems (Fragnelli, Monella, and Ortona Reference Fragnelli, Monella and Ortona2005). This tool is used to measure the difference in ethnoracial representation between each country’s total and incarcerated populations,Footnote 4 using the ethnic and racial categories employed by each country’s respective census, therein determining the overall extent of prison disproportion for each case. This approach avoids the hazard of producing false equivalencies between groups in differing countries and allows the analysis to include any country that makes data available. The extent of disproportion found is represented by a “disproportionality index” by which countries are ranked and compared. I also provide a “range of representation” between the least and most incarcerated census categories in each case, which provides a cross-reference for the disproportionality indices in addition to providing further context.

The findings demonstrate that conspicuous levels of ethnoracial disproportion are typical, and may even be ubiquitous, in contemporary democracies. The extent of disproportion found in each case is also significant: even in countries with the most comparatively proportional prison populations, the most overrepresented census categories are shown to bear at least twice the risk of incarceration compared to their counterpart groups. In some cases, the risk of incarceration for the most overrepresented census categories was found to be more than thirty times that of their counterparts.

A preliminary analysis of socioeconomic and criminal justice factors shows that countries with more desirable ratings on the Human Development Index, World Happiness Report, and Democracy Index tended to have more ethnoracially disproportionate prison populations. However, these correlations were very weak. Further, more economically equal countries with smaller prison populations, lower incarceration rates, and fewer homicides are shown to have only marginally more proportionate prison populations compared to countries with less desirable conditions. For example, nations of northwestern Europe are found to have some of the most ethnoracially disproportionate prisons populations among the cases. Though hardly exhaustive, this analysis demonstrates that prison disproportion is not easily predicted by routinely compared national benchmarks.

Overall, the evidence suggests that despite considerable variation in the cultural and national conditions of the cases, ethnoracial prison disproportion is an unfortunate shared feature of many contemporary democracies. This is not to suggest that it only occurs in democracies; authoritarian societies likely fare no better and perhaps worse, although this needs to be confirmed by future studies. Nonetheless, it is significant that societies sharing a common set of liberal values—including the principle that ascriptive identity be neither an advantage nor disadvantage—are found to exhibit a potential indicator of widespread illiberalism, that is, a condition in which ascriptive identity correlates with risk of incarceration. The discussion considers the role of social inequality in producing such a pattern and also proposes that democracies may tend to implement criminal justice in such a way that pushes the punitive energy of the state toward the margins of society.

The article is organized as follows: first, I review the literature on previous cross-national studies of ethnic and racial disproportion in prisons. Next, I detail my method and discuss how it overcomes previous limitations impeding broad cross-national comparisons across large numbers of countries with distinct ethnic and racial populations. My findings demonstrate that ethnic and racial disproportion in prisons is a global issue that afflicts not only high-incarcerating countries with conspicuous histories of ethnoracial oppression but also countries with comparatively progressive penal regimes. I then discuss a selection of the cases in further detail to examine how well the method captures actual conditions. Last, although space does not permit a fully developed cross-national theory explaining this study’s findings, the discussion considers a causal hypothesis that complements existing understandings of why prison disproportion occurs.

LITRATURE REVIEW

Previous cross-national comparisons of ethnoracial disproportion in prisons have been insightful yet limited, primarily due to methodological challenges. Cross-national comparison is typically premised on standardizing across cases; however, two challenges arise from efforts to standardize across cases when examining prison demographics. First, the heterogeneity of ethnic and racial categories across countries is impossible to standardize; countries not only use differing categories but also differing numbers of categories (Tonry Reference Tonry1997). Second, given that census categories between countries are usually incongruent, researchers may be tempted to create their own categories or use unofficial ones—this risks inadvertent production of false equivalencies between groups in various countries. Although groups that experience comparable risks of incarceration within their respective countries may socioeconomically overlap in some respects, this does not necessarily justify their conflation into a single grouping.

To provide a concrete example of the first challenge—that of standardizing census categories across countries—consider that the United States recognizes four ethnic and racial categories in its current prison census and Australia recognizes only two. Both countries are known for significantly disproportionate prison populations, yet the mismatch in terms of census categories makes them seemingly tricky to compare. If one were to compare the United States and Australia in terms of their respective ethnic and racial incarceration rates, one would also have to select which groups on the US side to exclude and which groups to match, thereby not only risking false equivalencies but also arbitrarily excluding some groups from the analysis altogether. Hence, the heterogeneity of census categories poses a challenge to cross-national research on prison demographics.

To provide a concrete example of the second challenge—that of matching disparate groups for comparison—consider that persons of African heritage in both the United States and United Kingdom experience a much higher likelihood of incarceration compared to any other group within their respective countries—in fact, persons of African heritage in England and Wales have at times experienced a greater likelihood of incarceration than Black Americans (Glynn Reference Glynn2013, 5). Given the shared heritage and similar carceral experiences, it would seem to some that the two groups are standardized by default and thus comparable. However, these two groups have been shown to statistically differ when it comes to important social factors such as marriage and residential segregation, both of which are found to impact risk of incarceration (Crutchfield and Weeks Reference Crutchfield and Weeks2015). For example, Black Britons are far more likely to marry someone of non-African origin than are Black Americans and are much less likely to experience residential segregation (Loury et al. Reference Loury, Modood and Teles2005, 178). In other words, Black Britons experience more “integration” compared to Black Americans, yet incarceration rates for the two groups are comparable. This is counterintuitive to theories that posit integration as lowering contact with criminal justice systems (Wilson Reference Wilson2012; Massey and Denton Reference Massey, Denton and Grusky2019). The larger point, however, is that arbitrarily matching different groups in different countries based on a perceived similarity risks producing false equivalencies and reinforcing essentialization. Furthermore, as my method will demonstrate, drawing equivalencies between groups in different countries is unnecessary.

Despite the methodological challenges inherent to comparing prison demographics, scholars have had some success implementing cross-national analyses of ethnic and racial incarceration rates; the work of Michael Tonry is notable in this regard. To test the assumption that the United States is indeed exceptional in terms of its ethnoracially disproportionate criminal justice system, Tonry (Reference Tonry1994) examines ethnic and racial incarceration rates in five English-speaking countries. Instead of trying to match groups cross-nationally, Tonry organizes respective countries’ ethnic and racial groups into white/other binaries. For example, Tonry compares the incarceration rates of “Whites and Natives” for Canada and “White and Blacks” for England and determines the ratio between the rate for the most incarcerated group and the rate for the least incarcerated group for each country. These ratios are then compared against each other. This achieves a cross-national comparison of ethnic and racial incarceration rates that somewhat overcomes the heterogeneity of racial identity categories in national censuses. In each of the five cases, Tonry finds that “disadvantaged visible minority groups are seven to 16 times likelier” to be incarcerated compared to their white counterparts (97).

Tonry concludes that racial disproportion in US prisons is not exceptional, but rather fits a pattern that stretches across the English-speaking world. Tonry interprets these findings as suggesting that the causes of racial disproportion in US prisons have less to do with criminal-justice-specific discrimination and more to do with racialized economic marginality. Comparing Australia, Canada, England and Wales, and the United States “exposes the failure of social policies aimed at assuring full participation by members of minority groups in the rewards and satisfactions of life in industrialized democratic countries” (1994, 97). Subsequent work by Tonry (Reference Tonry1997) observes that “members of some disadvantaged minority groups in every Western country are disproportionately likely to be arrested, convicted, and imprisoned for violent, property, and drug crimes” (1).

Although it uncovers important findings, Tonry’s method has limitations. The method limits the number of countries that can be included in the analysis by relying on perceived cultural similarity to construct the data set. That is, the method is essentially limited to settler societies and, in these cases, their shared English colonial origins. Furthermore, although pairing the least and most incarcerated group in each case provides a picture of disproportion in each country, we are left wondering about the many groups in between the extremes and whether their carceral experience fits the national pattern. Moreover, Tonry’s method excludes groups that are minorities in both the total population and prison population but nonetheless may be significantly overrepresented in prisons, such as indigenous communities in the United States. Such an approach reinforces the invisibility of groups typically overlooked in discussion of punishment and racial justice (Ramos Reference Ramos2016).

A more recent study by Crutchfield and Pettinicchio (Reference Crutchfield and Pettinicchio2009) builds on the work of Tonry and includes more countries—fifteen in total—to consider the association between public attitudes regarding inequality and incarceration rates of overrepresented groups. The purpose is less to measure specific extents of prison disproportion and more to explain the causes of disproportion. Encountering the same challenges of standardization that drove Tonry to innovate, the authors essentially employ an other/non-other binary with which to compare countries. The authors contend that “if we use race to measure, in part, the percentage of others in U.S. prisons, while using the percentage of aliens as a measure in the Netherlands, the results may be expected to be fairly comparable” (138). In other words, “other” is used as an umbrella category capturing social exclusion based on both racialization and national origin, therein making the United States—in which the “other” is defined by race—and European countries—in which the “other” is defined by immigration status—comparable.

The results of the analysis show that higher incarceration rates of “others” can be associated with an increased cultural “taste” for inequality, that is, an attitude that “government is not responsible for ameliorating the causes and products of social and economic inequality” (135). The United States and the Netherlands show the highest levels of taste for inequality and also display the two highest percentages of “others” in prison, whereas lower taste for inequality is associated with more proportional prison populations. Importantly, this pattern holds despite the markedly differing economic and criminal justice characteristics of the fifteen cases, which suggests the importance of public tastes for inequality in contributing to prison disproportion (140). While this study potentially advances the causal thesis and does somewhat overcome the challenge of heterogenous categories of ethnoracial difference, reliance on an other/non-other binary potentially creates unfounded equivalencies between disparate groups experiencing disparate conditions and cannot illuminate specific overrepresentation of specific groups in each country. The authors may provide a clearer understanding of what contributes to prison disproportionalities—which was their primary goal—yet the global picture of prison disproportionalities remains less clarified.

Although cross-national studies of prison disproportion have tended to include a small number of countries due to the previously mentioned methodological challenges, Ruddell and Urbina (Reference Ruddell and Urbina2004) use a sample of 140 countries to test the relationship between ethnic and racial diversity and incarceration rates (912). The authors hypothesize that increasing ethnoracial diversity will correspond with increasing prison populations when controlling for other factors such as economic stress, rates of violent crime, modernization, and political stability; this is the concept of “minority threat.” Using Ethnolinguistic Fractionalization (ELF)—which captures overall national diversity by estimating the likelihood that any two random persons within a country will differ in terms of ethnoracial identity—the authors conclude that population heterogeneity increases incarceration rates, therein presumably resulting in greater extents of prison disproportion (924). However, the authors concede that their methods are unable to observe “who,” specifically, becomes overrepresented in prisons (925). This is because ELF, as a measure of raw diversity, cannot help in specifying which groups are more punished than others. While the study provides evidence that minority threat is a factor in punitiveness, the extent and specifics of global prison disproportion remain, again, unclear.

The overrepresentation of ethnic and racial minority groups in prisons has been acknowledged as globally extensive by the United Nations (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2021). However, systematic comparisons have remained elusive, primarily because of the heterogeneity of identity categories in national censuses. Tonry (Reference Tonry1997) advocates for the “development of a comprehensive research agenda” that “move[s] beyond single-country analyses” to clarify this global pattern (36). With this in mind, I use a method for comparing ethnic and racial proportions between incarcerated and total populations that overcomes the heterogeneity of census categories while avoiding the risk of arbitrary cross-national groupings.

CURRENT STUDY

Summary of the Method

To overcome the challenge of standardizing identity categories across countries, I use a modified version of the Ortona Index, which was originally developed to analyze proportional electoral systems “based on the difference between seats assigned by a given electoral system and seats assigned by a perfect proportional system” (Fragnelli, Monella, and Ortona Reference Fragnelli, Monella and Ortona2005, 1655). In other words, the Ortona Index has been used to compare an actual instance of electoral representation—such as that which emerges in a given year of a parliament—against what would be expected based on popular support for various political parties. Ideally, electoral representation and popular support of parties would correspond exactly in a democracy, yet for various reasons, this may not always be the case. Using the example of the Russian Parliament of 1995, the authors show through the Ortona Index that party representation during that year was more disproportionate compared to other years, which invites further analysis to explain why (1659). A similar methodological approach may be used to analyze prison disproportionalities because contemporary criminal justice systems—like electoral systems—are premised on fairness and desert. That is, it is a basic democratic principle that persons, whether sitting in parliament or behind bars, arrived where they are through a fair process that determined their deservedness. Given that disproportion is a possible indicator of unfairness or dysfunction in both electoral systems and punishment, a method to measure disproportion in one may be applicable to the other.

Hence, I have modified the Ortona Index to analyze prison demographics. Specifically, I have adapted the Ortona Index to analyze percentages rather than raw counts, as it was originally constructed to do. This is because incarcerated and total population data that accounts for categorical differences is typically offered in the form of percentages rather than full counts given the sheer numbers at hand. I use this method to compare individual countries against an ideal scenario in which an incarcerated population and total population have the same ethnic, racial, and indigenous proportions. By “ideal,” I mean that ethnoracial congruence between an incarcerated and total population would strongly suggest that ethnoracial identity is not associated with risk of incarceration, which in turn would suggest a low or nonexistent occurrence of bias in a justice system and/or a maximally inclusive society. Cases are compared against each other in terms of their proximity to this ideal. The most suitable data for such comparison disaggregates a given national incarcerated and total population according to that country’s own ascriptive census categories.

TARGET YEAR, DATA, AND CASE SELECTION

Target Year

This study uses a novel data set to analyze eighteen democracies across six continents for the year 2016. 2016 was chosen as both a recent and “normal” year, unimpacted by the global COVID-19 pandemic and intersecting with many countries’ decennial census cycles. If 2016 data was unavailable for a country that provides demographic prison data otherwise, then data was collected for the closest year, ranging from 2010 to 2020. Prison populations are subject to fluctuations year to year; however, evidence suggests that prison demographics generally shift over the course of a decade or more, even after implementation of new policy and practices (Kang-Brown et al. Reference Kang-Brown, Hinds, Heiss and Lu2018, 6). Thus, a single year of data provides a reasonable snapshot of prison demographics.

Data

Data was gathered primarily from publicly available and Internet-searchable national justice statistics that disaggregate incarcerated populations according to ethnic and racial categories—or, in some cases, suitable proxies such as caste—along with national census data that also disaggregates total populations using the same categories. If such data was not available from national statistics it was sourced from nongovernmental organizations, research organizations, and previous research. Data availability was the primary determinant of case selection.

Case Selection

As previous cross-national studies have encountered, case selection can drive results and the case-selection process must be as transparent as possible to compensate for this tendency (Gertz and Myers Reference Gertz and Myers1992). The case-selection process began by first identifying countries categorized as “full” or “flawed” democracies according to the Democracy Index for 2019, which produced a list of seventy-five potential cases with stated commitments to honoring basic civil rights and implementing a fair and transparent criminal justice process (Economist Intelligence Unit 2020).

Next, this list of seventy-five countries was cross-referenced against the World Prison BriefFootnote 5 to identify countries that make ethnic and racial data on prisoners publicly available. It was quickly determined that most countries do not make this sort of data available or easily accessible and rather merely report the number of “foreigners” in their prisons. Twelve countriesFootnote 6 were initially identified as providing the most suitable kind of data for this study, that is, breakdowns of their incarcerated population according to racial and ethnic census categories in approximately 2016.

However, this initial set of twelve democracies—compiled solely based on available data—excluded some penologically notable countries in Europe and was dominated by settler societies of British origin. Thus, to enhance the variation in the data set, Norway and Germany—both argued by some to be model implementers of criminal justice—were added using their official justice statistics distinguishing the percentage of “foreigners” in their prisons. Given the historical ethnic homogeneity of their respective populations, an official category of “foreigner” likely includes racial and ethnic minorities (Crutchfield and Pettinicchio Reference Crutchfield and Pettinicchio2009). Further, though both Norway and Germany are known to have disproportionate prison populations (Albrecht Reference Albrecht1997; Ugelvik Reference Ugelvik, Pickering and Ham2017), it has remained unclear how they compare to other countries, particularly a country such as the United States, which has become notorious for minority overrepresentation in incarceration. That is, it has remained unclear whether penal progressivism corresponds with more proportional prison populations; including Norway and Germany allows for a consideration of this interesting question.

So too did lack of specific ethnic and racial prison statistics initially exclude several populous, historically influential, and penologically interesting European democracies—namely Italy, France, and Spain. These countries were also added using their distinction of “foreigners” in prisons such that the European penal progressives were not singled out among their more arguably punitive neighbors. Finally, in noticing that all the European cases ranked very highly on the Democracy Index, Greece was added as an example of a European “flawed” democracy to enhance the data set variation with regard to democratic development. These additions expanded the total cases to eighteen, covering an appreciably wide range of national conditions among democracies. Also, these latter inclusions allow for some consideration of whether prison disproportion is primarily an issue confined to countries that collect specific ethnic and racial data on their prisoners. As the findings demonstrate, this is not the case.

Other Data Exceptions

India was included using officially furnished census categories of caste, which corresponds with ethnic and racial distinctions used in Western democracies in terms of associating with statistical likelihood of socioeconomic inequality and discrimination (Pandey Reference Pandey2013). Also, I was able to uncover German data on prisoner religious self-identification, which allows a second analysis of German prisons beyond the “foreigner/citizen” dichotomy. Both countries are discussed in further detail in the single-country analyses following the findings.

Data Issues and Underestimation

Available public data on ethnoracial proportions of incarcerated populations is of varying quality, thus the findings should be regarded as estimates. For example, totals for some cases do not add up to 100 percent due to assumed collection errors. In general, census practices in many countries lead to an underestimation of prison disproportion through practices such as the counting of ambiguous categories like “other,” which likely include variously represented groups in prisons. The problem of underestimating disproportion is perhaps most acute in countries that analyze their prison and total populations using a distinction of “foreign/citizen”; the “citizen” category may include overrepresented minority groups, therein obfuscating the true extent of prison disproportion.

EXPLANATION OF METHOD

As previously mentioned, the current study utilizes a modification of the Ortona Index to facilitate cross-national comparison of prison disproportion. I construct two interrelated metrics for each case. The first is a disproportionality index (d c ), which represents the mean level of disproportion in incarceration across all census categories used in a given country’s census. The second metric is the range of representation (r c ), which shows the disparity in incarceration between a country’s most underrepresented and most overrepresented category—this serves as an important cross-reference to the disproportionality indices, compensating for the fact that a greater number of census categories observed by a given country can skew a disproportionality index toward indicating a more proportional prison population. The formula for the disproportionality index is:

$${d_c} = {{\sum\nolimits_{i \in N} {\left| {1 - \left( {{{P_i^I} \over {P_i^T}}} \right)} \right|} } \over {{n_c}}}$$

$${d_c} = {{\sum\nolimits_{i \in N} {\left| {1 - \left( {{{P_i^I} \over {P_i^T}}} \right)} \right|} } \over {{n_c}}}$$

The calculation has two steps and is used to analyze each country separately. First, I measure the ratio of representation between the incarcerated population and total population for each category within the census; this is the “representation ratio”

![]() $\;\left( {{{P_i^I} \over {P_i^T}}} \right)$

. A representation ratio of “1” would indicate perfect proportionality, that is, a 1-to-1 ratio between the incarcerated and total population for a particular census group. A representation ratio below 1 indicates underrepresentation and a representation ratio over 1 indicates overrepresentation.

$\;\left( {{{P_i^I} \over {P_i^T}}} \right)$

. A representation ratio of “1” would indicate perfect proportionality, that is, a 1-to-1 ratio between the incarcerated and total population for a particular census group. A representation ratio below 1 indicates underrepresentation and a representation ratio over 1 indicates overrepresentation.

The case of the United States may be used to demonstrate the construction of representation ratios. The United States used four census categories in 2016. The total US population

![]() $\left( {P_i^T} \right)$

was counted as 61 percent “White (non-Hispanic),” 13.4 percent “Black,” 18.5 percent “Hispanic,” and 8 percent “Other.” During the same year, the incarcerated population

$\left( {P_i^T} \right)$

was counted as 61 percent “White (non-Hispanic),” 13.4 percent “Black,” 18.5 percent “Hispanic,” and 8 percent “Other.” During the same year, the incarcerated population

![]() $\left( {P_i^I} \right)$

was counted as 30.2 percent “White (non-Hispanic),” 33.4 percent “Black,” 23.2 percent “Hispanic,” and 13.3 percent “Other.” Dividing

$\left( {P_i^I} \right)$

was counted as 30.2 percent “White (non-Hispanic),” 33.4 percent “Black,” 23.2 percent “Hispanic,” and 13.3 percent “Other.” Dividing

![]() $\left( {P_i^I} \right){\rm{\;}}$

by

$\left( {P_i^I} \right){\rm{\;}}$

by

![]() $\left( {P_i^T} \right)$

indicates the extent to which a group is represented in the incarcerated population. In the case of the United States, whites were underrepresented at 49 percent and every other group was overrepresented, with the category “Black” being represented at 250 percent of their proportion of the total population (see Table 1).

$\left( {P_i^T} \right)$

indicates the extent to which a group is represented in the incarcerated population. In the case of the United States, whites were underrepresented at 49 percent and every other group was overrepresented, with the category “Black” being represented at 250 percent of their proportion of the total population (see Table 1).

Table 1. Census Category Representation and Disproportion Ratios for United States, 2016

Note: Source for total population statistics: U.S. Census Bureau; American Community Survey, 2016 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates, Table DP05; using data.census.gov; (8 April 2021).

Source for total population statistics: Source for incarcerated population by race and ethnicity statistics: E. Ann. Carson. “Prisoners in 2018.” Ethnicity 2008 (2018): 2-000. https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/p16.pdf.

To then calculate the disproportionality index (

![]() ${d_c}$

) for the United States, the absolute difference is measured between the disproportion ratio for each group and perfect proportion, that is, 1. Then the results for each category are summed and divided by the total number of census categories analyzed, which allows countries with differing numbers of census categories to be compared. This produces a disproportionality index for the United States of .73, which is, surprisingly, about average for the sample. Disproportionality indices cannot be negative and have no upper limit; any number above 0 indicates disproportion, with larger numbers representing a greater difference between the incarcerated and total populations (see Table 2).

${d_c}$

) for the United States, the absolute difference is measured between the disproportion ratio for each group and perfect proportion, that is, 1. Then the results for each category are summed and divided by the total number of census categories analyzed, which allows countries with differing numbers of census categories to be compared. This produces a disproportionality index for the United States of .73, which is, surprisingly, about average for the sample. Disproportionality indices cannot be negative and have no upper limit; any number above 0 indicates disproportion, with larger numbers representing a greater difference between the incarcerated and total populations (see Table 2).

Table 2. Disproportion Ratios and Disproportionality Index for United States, 2016

Findings of no difference (i.e., “0”) were not expected given known contributors to prison disproportion, particularly socioeconomic inequality, which afflicts all contemporary democracies. The United States, which is well known for a disproportionate prison population, can be thought of as a basis for comparison to evaluate the variation in disproportionality indices.

(

${d_c}$

) Right-Side Bias and Under/Over Representation

${d_c}$

) Right-Side Bias and Under/Over Representation

The measure of disproportionality indices takes advantage of the “right-side bias,” which stems from analyzing percentages via a modified Ortona Index. Both underrepresentation and overrepresentation in prisons are forms of disproportion and because this method is based on absolute difference, both contribute positively toward a country’s disproportionality index. However, this method does not treat both manifestations of disproportion as normative equivalents. Ethnic and racial overrepresentation in prisons is associated with collateral negative impacts on marginalized communities and various ethnic and racial disparities more broadly, whereas underrepresentation is typically viewed as a group advantage (Gottschalk Reference Gottschalk2011). Because a census category cannot be underrepresented below 0 percent, underrepresentation will contribute a maximum value toward disproportionality indices of 1, whereas there is no upper limit to how much overrepresentation will drive indices upward. Hence, the method has a justifiable right-side bias.

Range of Representation

In addition to the disproportionality indices, I provide a range of representation (

![]() ${r_c})$

between the most underrepresented

${r_c})$

between the most underrepresented

![]() $\left( {{{P_u^I} \over {P_u^T}}} \right)$

and most overrepresented

$\left( {{{P_u^I} \over {P_u^T}}} \right)$

and most overrepresented

![]() $\left( {{{P_o^I} \over {P_o^T}}} \right)$

categories for each case. The use of mean to calculate the disproportionality index can potentially “soften” results for countries with more census categories, resulting in lower disproportionality indices. Means are typically paired with ranges for this reason. Cross-referencing a given disproportionality index with the range shows the disparity between the least and most incarcerated groups in terms of the extent to which ethnic and racial categorization associates with risk of incarceration. For example, a given country’s range may show that the least incarcerated category is only incarcerated at 0.25 times its representation in the total population whereas the most incarcerated group is incarcerated at eight times its representation in the total population. This clarifies whether disproportionality indices are driven primarily by underrepresentation or overrepresentation, and to what extent. To find the range of representation, I rank order the representation ratios from lowest to highest, identify the most underrepresented and most overrepresented categories, and present the data as such:

$\left( {{{P_o^I} \over {P_o^T}}} \right)$

categories for each case. The use of mean to calculate the disproportionality index can potentially “soften” results for countries with more census categories, resulting in lower disproportionality indices. Means are typically paired with ranges for this reason. Cross-referencing a given disproportionality index with the range shows the disparity between the least and most incarcerated groups in terms of the extent to which ethnic and racial categorization associates with risk of incarceration. For example, a given country’s range may show that the least incarcerated category is only incarcerated at 0.25 times its representation in the total population whereas the most incarcerated group is incarcerated at eight times its representation in the total population. This clarifies whether disproportionality indices are driven primarily by underrepresentation or overrepresentation, and to what extent. To find the range of representation, I rank order the representation ratios from lowest to highest, identify the most underrepresented and most overrepresented categories, and present the data as such:

The range of representation can also clarify unexpected results. For instance, while Australia’s disproportionality index is 4.5, the US index is lower at 0.73, which means Australia’s incarcerated population is more disproportionate than that of the United States. This may be surprising based on the notoriety of American racial disparities in punishment. However, the range of representation for Australia is [.75, 9.7] and for the United States it is [.49, 2.5]. As can be seen, the range of representation is indeed greater in Australia than the United States, thus it makes sense that Australia’s prison population is more disproportionate overall compared to that of the United States.

FINDINGS

Taken as a whole, the findings demonstrate that ethnoracial disproportion in prisons is extensive among democracies, even in countries that are safer and more socioeconomically egalitarian than the United States. The extent of prison disproportion among all cases is significant; even in the most proportional countries, overrepresented ethnic and racial groups are imprisoned at least twice as much as the least incarcerated group.

The findings are presented as a lineup of cases according to their disproportionality index and range of representation. The two lowest- and highest-scoring countries, as well as countries that exhibit unexpected results, receive single-country analyses—this exemplifies how the method is intended to be used as a guide for further research rather than as a conclusive framework (see Table 3).

Table 3. Disproportionality Indices and Range of Representation

* Citizenship or national origin status used as proxy for race/ethnicity.

SOCIOECONOMIC AND CRIMINAL JUSTICE CHARACTERISTICS

The eighteen cases vary considerably in terms of their socioeconomic and criminal justice characteristics, providing an opportunity to examine the correlation, at least preliminarily, between these factors and ethnoracial disproportion in prisons. Findings may help clarify why prison disproportion varies among countries. One hypothesis is that prison disproportion would be higher under relatively inegalitarian social conditions, such as greater extents of economic inequality and less developed democratic institutions. This could be expected because marginalized groups may experience a greater extent of socioeconomic exclusion under such conditions, which contributes to increased risk of criminal involvement.

HDI, WHR, and Democracy Index

Two significant correlations were identified between the findings and benchmarks of economic and democratic development. Specifically, countries with more desirable ratings on the Human Development Index and Democracy Index tended to have more ethnoracially disproportionate prison populations, though the relationship is only moderate. This is perhaps counterintuitive considering that more desirable ratings on these indices are associated with greater protections of minority groups and a fairer justice process.

As previously mentioned, ethnoracial disproportion in prisons is theorized to emerge from several intersecting factors, many of which involve some form of social or economic exclusion that is conceivably reinforced by reliance on incarceration (Sampson and Lauritsen Reference Sampson and Lauritsen1997). Given that theories of innate group criminality are refuted (Pate Reference Pate2014), the extent of demographic disproportion in a country’s prisons may thus be seen as a bellwether of inclusiveness within its polity. Thus, it is surprising to see that countries that rate higher on national indices associated with social inclusivity and openness of government have more disproportionate prison populations. Although “higher degrees of political repression or autocracy are hypothesized to be significantly associated with the use of punishment,” these hypotheses have primarily applied to analyses of overall national incarceration rates and not ethnoracial disproportion in prison specifically (Ruddell and Urbina Reference Ruddell and Urbina2004, 917–18).

One potential explanation for this finding is that countries with more desirable political characteristics receive a greater influx of immigrants, who are then at increased risk of criminal involvement due to socioeconomic exclusion and/or increased risk of discrimination by police (Wacquant Reference Wacquant1999). This possibility seems applicable to many European countries but does not extend elsewhere, as least contemporarily. For example, noncitizens tend to be underrepresented or proportionally represented in US prisons (Bronson and Carson Reference Bronson and Carson2019). Overall, the correlation between prison disproportion and democratic development, though hardly conclusive, challenges assumptions that illiberal outcomes in incarceration are confined to more conspicuously illiberal places (see Table 4).

GINI

If group differentials in criminal involvement are contributing to disproportion in prisons, then more equal economic conditions may lessen pressure on marginalized groups to engage in illicit behavior. However, countries that rated lower on the GINI index (more economically equal) are shown not to have significantly more proportional indices compared to their less economically equal counterparts. Countries such as Australia, Norway, and Finland have some of the most desirable GINI coefficients in the world and also some of the most disproportionate prison populations, nonetheless. The full benefits of residing in these comparatively egalitarian countries are known to be unevenly distributed across ethnic, racial, and indigenous divides (Fritzell, Bäckman, and Ritakallio Reference Fritzell, Bäckman, Ritakallio, Kvist, Fritzell, Hvinden and Kangas2012). However, it remains surprising that overall economic equality matters so little with respect to prison demographics (see Table 4).

Criminal Justice Factors

In terms of criminal-justice-specific benchmarks, the correlations were more intuitive, though still insignificant. Democracies with smaller prison populations, lower incarceration rates, and fewer homicides tended to have more proportional prison populations. However, even among such countries, the disproportion of the imprisoned population was conspicuous and perhaps exceeding expectations. The findings presented little evidence that ethnic and racial disproportion in prisons is simply a consequence of higher crime rates or even a larger prison population.

The generally weak correlations between the findings and national-level socioeconomic and criminal justice characteristics suggests that prison disproportion—both in terms of its existence and variation—is not easily clarified through standard measures of national conditions. Prison disproportion afflicts democracies of varying development and with distinct sociocultural and historical traits. The following selection of single-case analyses takes a closer look at the findings by exploring the highest and lowest disproportionality indices and cases of particular interest. This exercise further reinforces that comparable extents of prison disproportion occur under a wide variety of conditions and in unexpected places (see Table 4).

Table 4. Correlation of Disproportionality Indices

Note: This table shows correlation of disproportionality indices with homicide rate (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2019), incarceration rate (Fair and Walmsley, Reference Fair and Roy2016), incarcerated population (Fair and Walmsley, Reference Fair and Roy2016), GINI (OECD, Reference Income Inequality2016), Human Development Index (Human Development Report, 2016), World Happiness Rating (Helliwell, Layard, and Sachs, Reference Helliwell, Richard and Jeffery2016) and the Democracy Index (Economist Intelligence Unit 2020).

*p<0.1

SINGLE-COUNTRY ANALYSES

Lowest Disproportionality Indices

India and Germany were found to have the most proportional prison populations. Although they both compare favorably against the other cases, they nonetheless demonstrate that even the most proportional justice systems yet identified are characterized by significant ethnoracial disparity. Further investigation reveals supporting evidence.

India

India was analyzed according to official categories of caste, which overlaps with notions of ethnic and racial difference elsewhere. This is not to say that race and caste are equivalent, but rather that both are recognized as social statuses within hierarchical societies that associate with access to opportunity and discrimination and thus can be theoretically related to risk of incarceration (Beteille Reference Beteille2020).

In India, the diverse caste of “Scheduled Tribes,” also known contentiously as “Adivasis”—or “original settlers” in Hindi—is the most overrepresented census category in Indian prisons. The Scheduled Tribes category faces twice the risk of incarceration compared to the least imprisoned caste and was overrepresented in prisons at 161 percent of its share of the total population during 2015. To place this disproportion in perspective, India’s Scheduled Tribes face risks of incarceration similar to some estimates of Black American risk in the early twentieth-century United States during the height of Jim Crow (Perkinson Reference Perkinson2010).

India’s Scheduled Tribes are known to experience both overt and implicit discrimination alongside a significant inequality of opportunity, all of which are theorized to contribute to overrepresentation in prisons (Harriss-White and Prakash Reference Harriss-White and Prakash2010). Caste discrimination continues to be an ongoing issue in India despite significant efforts to curtail exclusion (Jaffrelot Reference Jaffrelot2010). Given this, the comparative proportionality of India’s prison population was a somewhat surprising finding. One possible explanation is that postcolonial reliance on incarceration in India has remained limited due to budgetary constraints (Nagda Reference Nagda2016). Other, less costly processes of social control may currently substitute for incarceration in India in a way similar to how racial segregation is theorized to have done so during the Jim Crow era of the United States (Alexander Reference Alexander2012). Thus, India’s comparatively proportional prison population may be a consequence of limited “legal capacity”—that is, capacity to adjudicate and punish—rather than a successful balancing of caste justice and crime control.

Another potential factor in India’s comparatively favorable disproportionality index is that the Indian census tracks four categories—at the high end within the sample—and that underrepresentation among three of the four groups is lowering the overall mean of disproportion. However, India’s range of representation is comparatively narrow at [0.75, 1.64], which supports the finding of a more proportional prison population. In contrast, the United States also tracked four census categories during 2016 and has both a considerably higher disproportionality index of .73 and a wider range of representation at [0.49, 2.5]. Thus, there is some confidence that India’s prison population is the most proportional of the sample, but the extent of disproportion is still troubling with regard to the possibility of systemic discrimination and/or socioeconomic exclusion.

Germany

Germany was included in the sample based on its tracking of “foreigners” in its prisons and because the country—which can boast a progressive penal regime, low recidivism rate, low incarceration rate, and humane prison conditions—is considered a leader in criminal justice implementation (Frase and Weigend Reference Frase and Weigend1995). Despite Germany’s admirable criminal justice characteristics, “foreigners”—a catchall category encompassing a diversity of ethnic and racial groups—are shown to be overrepresented in German prisons at 150 percent of their share of the total population. This is a greater extent of overrepresentation than can be shown for the “Hispanic”Footnote 7 category in the United States, which was overrepresented in 2016 at approximately 125 percent. Thus, although Germany’s disproportionality index is comparatively favorable, it is still reasonably interpreted as problematic from a point of view emphasizing ethnic inclusivity. A further analysis using religious self-identification may reveal even more disproportion than the official statistics based on citizenship status.

Foner (Reference Foner2015) argues that “the strong religious divide between Muslims and the secular/Christian majority in much of Western Europe operates … in some ways like the stark social cleavages involving people and groups of visible African ancestry in the United States” (897). The Turkish and Arab communities of Germany report a high religious affiliation, thus religious self-identification serves as a proxy of ethnic difference (Foroutan Reference Foroutan2013). In a second analysis using this proxy, self-identified Muslims, which made up about 6 percent of Germany’s total population, were estimated by some sources to be 19 percent of the prison population, or 311 percent of their representation within the total population (Pew Research Center 2017; Klaiber Reference Klaiber2018). However, official German prison statistics do not track prisoners according to religious self-identification and this remains an estimate, which, due to Islamophobia, may be overstated (Cherribi Reference Cherribi, Esposito and Kalin2011). If this estimate is accurate, recalculating Germany’s disproportionality index based on these disparities places it well above the United States, at 1.1. Based on research that religious minorities within the Citizen category in Germany are subject to disproportionate “police-initiated contact,” it is reasonable to suspect that German prisons are more disproportionate than official statistics make clear (Bierbrauer Reference Bierbrauer1994; De Maillard et al. Reference De Maillard, Hunold, Roché and Oberwittler2018).

Highest Disproportionality Indices

The most disproportionate prison populations found were those of Ireland and Switzerland. As neither are often mentioned in the context of prison disproportion, their arrival of at the top of the list was unexpected. Both demonstrate that even a small prison population can be extremely disproportionate.

Ireland

The extreme disproportion of Ireland’s prisons is driven primarily by the overrepresentation of Irish Travellers, who are one in every ten prisoners despite being just 0.6 percent of the total population (Stanton Reference Stanton2017). Irish Travellers have long been considered culturally distinct from “settled” Irish and succeeded in having their ethnic identity recognized by the Irish government in 2017 after many decades of advocacy. This recognition is vital considering that Travellers experience significantly more poverty and discrimination compared to the settled population (O’Connell Reference O’Connell1997). In this regard, Irish Travellers face similar challenges to the Romani peoples of continental Europe, which include “increased surveillance by police due to their status as deviant or ‘other’” (Donnelly-Drummond Reference Donnelly-Drummond2015, 22).

The case of Ireland demonstrates that even relatively small prison populations, in this case one consisting of just 7,484 persons, are capable of extreme disproportion. However, the index for Ireland is still likely an underestimate. Foreign nationals are overrepresented in Irish prisons at 195 percent of their proportion of the total population, which suggests that immigrant communities, which include Irish citizens, experience disproportionate contact with police. For example, the killing of George Nkencho in 2021 marked the first death of an African-Irish community member in connection to Irish police and sparked weeks of protest against the disparate treatment of the African-Irish community by authorities (Murphy Reference Murphy2021). Thus, Ireland’s distinction between “Citizen” and “Foreigner” in prison statistics likely obscures overrepresented groups within the Citizen category.

Switzerland

Switzerland’s disproportionality index is the second highest in the study. However, Switzerland’s index may be partly the result of how the Swiss government counts its prison population. Rather than split the prison population into a binary of “Swiss” and “foreign,” as its European neighbors tend to do, the Swiss break down the “foreign population” into three separate categories: “foreign residents,” “asylum seekers,” and a catchall category of “status unknown,” which comprises “foreigners with no fixed residence in Switzerland, cross-border workers with a G permit, [and] undocumented migrants and tourists” (Islas Reference Islas2019). Foreign residents, like Swiss nationals, are underrepresented in Swiss prisons, though not nearly to the same degree. Swiss nationals only make up 32 percent of the prison population while being 73 percent of the total population, whereas foreign nationals make up 22 percent of the prison population and 26 percent of the total population. The remaining half of all prisoners in Switzerland are drawn from the categories of “asylum seekers” and “status unknown,” which together were only 4.5 percent of the total population in 2017. Granted, the Swiss maintain a relatively small prison population of just under seven thousand persons in a country of over eight million. Nonetheless, the disproportion is extreme. The category of “asylum seeker” is 12 percent of the prison population while only accounting for 0.8 percent of the total population. Persons categorized as “status unknown” made up 34 percent of the prison population but only 3.75 percent of the total population. The Swiss case demonstrates that there is important diversity within the category of “foreign” that should be considered, further reinforcing that the binary of citizen/foreigner employed by most European countries likely minimizes the observable degree of ethnoracial disproportion in European prisons.

OTHER CASES OF INTEREST

The United States

The United States is well known for racial disparities in criminal justice. However, contrary to expectations, the US prison population does not rank even among the top ten most ethnoracially disproportionate. Expectations that the United States would have an exceptionally disproportionate prison population may be reasonably drawn from America’s well-documented history of systemic racism (Feagin Reference Feagin2013). Yet comparatively speaking, the American prison and total populations are shown to be more ethnoracially similar than those found in Western Europe.

However, disparities in American criminal justice are not overstated. First of all, it can be seen from the range of representation in the United States ([0.49, 2.5]) that the disparity between the most underrepresented category, “White not-Hispanic,” and the most overrepresented category, “Black,” is significant; five Black Americans are incarcerated for every one white American. A vast literature on racial disparities in American criminal justice provides overwhelming evidence that such disparities are persistent, pervasive, and strongly associated with devastating consequences for socially marginalized and economically isolated communities (Murakawa Reference Murakawa2014; Hinton Reference Hinton2017; Crump Reference Crump2019). Thus, the index for the United States is best interpreted as suggesting the enormity of ethnoracial prison disproportion as a global problem.

Moreover, it should be noted that the index for the United States is likely an underestimation of prison disproportion due to the way in which statistics of race and ethnicity are collected by the American Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS). Because many individual American states do not collect prison data on the census categories of “Asian,” “American Indian and Native Alaskan” (AIAN), and “Hawaiian Native and Pacific Islander” (HNPI), the BJS aggregates these groups into an “Other” category. This obfuscates the disproportion in American prisons. For example, 22,744 Native women and men were incarcerated during 2016 (Daniel Reference Daniel2020). That amounts to 11 percent of the total “Other” category in BJS statistics when the AIAN category only made up 1.3 percent of the US total population. The Prison Policy Initiative concludes that “until criminal justice agencies overcome the limitations on data collection—and until the offices that publish the data are willing to list Native Americans as a distinct demographic group, rather than a member of an ‘Other’ category—informational gaps will continue to make it difficult to understand how overcriminalization has impacted Native populations” (Daniel Reference Daniel2020).

Norway

Norway has been suggested as a model of criminal justice that other countries should follow, making the relatively small nation somewhat of a penological giant (Pratt and Eriksson Reference Pratt and Eriksson2014; Labutta Reference Labutta2016). Indeed, the Norwegian system is arguably worthy of emulation in several respects, including humane prison conditions, rational and evidence-based sentencing practices, and a low incarceration rate. Recidivism rates are also low, which indicates successful interventions. Thus, Norway’s comparatively high disproportionality index of 2.5 and comparatively broad range of representation [0.75, 5.83] may come as a surprise.

However, several scholars challenge the notion of “Nordic Exceptionalism,” which is often used to explain the seemingly benign character of criminal-legal systems in northern Europe. For example, Barker (Reference Barker2013) describes the Nordic penal regimes as “Janus-faced,” in part on account of the high proportion of foreign nationals in Nordic prisons. On the one hand, these regimes are progressive in their approach to punishment, and their approaches are “often put forward on normative grounds as best practices for penal moderation” (20). On the other hand, Nordic countries have “come to rely on the criminal law and penal sanctioning to sort, classify, contain, or expel unwanted or undeserving ‘others’” (21).

Foreign nationals in Norway are ethnically and racially diverse; thus, this citizenship status serves as a proxy for ethnic and racial difference (Skardhamar, Aaltonen, and Lehti Reference Skardhamar, Aaltonen and Lehti2014). The disproportionality index for Norway (2.5) is driven by a 580 percent overrepresentation of the “Foreign” category in its prisons, which, during 2012, made up 29 percent of the incarcerated population and only 5 percent of the total population. This finding supports Barker’s argument that the Norwegian system is indeed “Janus-faced.” Moreover, in distinguishing its prisoners as either “Norwegian citizen” or “Foreigner,” Norway obfuscates the true extent of disproportion in its prisons. There are likely ethnic and racial groups within the “Norwegian” category that are overrepresented in prisons, and this cannot be clarified until Norway chooses to count its prisoners beyond a citizen/foreigner dichotomy. One such group may be the Saami, the indigenous peoples of the Sápmi region, who have experienced discrimination and repression for centuries in Norway and other Scandinavian countries (Toivanen Reference Toivanen, Götz and Hackmann2017). Furthermore, Norway’s regional neighbor Finland, which is similarly progressive in its criminal justice approach, uses several categories of national origin in its prison census and is shown to have a more disproportionate prison population than Norway. Similar results might emerge for Norway if prison data were more complex.

Norway’s disproportionality index is 2.5, well above that of the United States. That said, its incarcerated population is comparatively tiny, and its prison conditions are arguably the best in the world (Johnsen, Granheim, and Helgesen Reference Johnsen, Granheim and Helgesen2011). Yet neither the Norwegian criminal justice system nor Norwegian society presides over anything approximating an ethnoracially equal opportunity to avoid incarceration. Whether this is due to ethnic differentials in offending, criminal-justice-specific bias, or some combination thereof, Norwegian criminal justice—despite its admirable qualities—cannot be discounted as an element within a larger process of ethnic exclusion currently pervading Norwegian society.

Brazil

Previous research on prison disproportion has focused on North America and Europe, but the issue extends to Latin America as well, including the most populous and economically powerful Latin American democracy, Brazil. Whereas every other country in this study is characterized by the overrepresentation of ethnic and racial minorities, the analysis of Brazil shows a racial majority as overrepresented. Brazilian Ministry of Justice statistics show that Black Brazilians make up 51 percent of the total population and 67 percent of the prison population, an overrepresentation of 131 percent (Ministério da Justiça 2015, 50). This challenges any assumption that minority-group status is a necessary condition for overrepresentation in prison. The disconnect between minority-group status and overrepresentation is further supported by looking at the United States: the most underrepresented census category in US prisons is “Asian,” which accounts for less than 6 percent of the total population and less than 1 percent of the prison population.

That said, the situation in Brazil still conforms to a pattern in which socioeconomic marginality correlates with overrepresentation in prisons. Although Black Brazilians are the numerical majority, they continue to experience socioeconomic and political marginalization relative to white Brazilians, who are the most underrepresented group in Brazilian prisons. This suggests the importance of social and economic marginalization in determining which groups experience the most contact with the criminal justice system, even when a group is counted by a census as making up a numerical majority.

South Africa

African countries have received little scholarly attention regarding prison disproportionalities. To my knowledge, the current study is the first to include South Africa in comparison with North American and European prison demographics. This inclusion was possible because South Africa—like several other of its Commonwealth counterparts—collects racial data on its prisoners. South African prisons are, overall, similarly disproportionate to those of the United States, with (

![]() ${d_c}$

)s of 69 and 73, respectively. The South African range of representation is comparatively wide at [0.19, 2], which indicates a significant disparity between the least and most incarcerated groups.

${d_c}$

)s of 69 and 73, respectively. The South African range of representation is comparatively wide at [0.19, 2], which indicates a significant disparity between the least and most incarcerated groups.

Given South Africa’s history of colonization and apartheid—and persistent post-apartheid wealth disparities between white and Black South Africans—it might be expected that—like Brazil—the Black majority of South Africa would be the most overrepresented in South African prisons (Orthofer Reference Orthofer2016). This is not so; Black South Africans are almost perfectly represented in South African prisons, and the census category of “coloured” is the most overrepresented, making up only about 8 percent of the total population but 18 percent of the incarcerated population.

The legal category of “coloured” reflects the British colonial and apartheid regimes’ difficulty in categorizing the diverse communities of the Western Cape, where a majority of persons would be thought of as “multi-racial” from an American point of view (Adhikari Reference Adhikari2005). In being legally defined under apartheid as neither “a white person nor a native,” the “coloured” category was positioned as a marginalized minority between the white ruling minority and the oppressed Black majority (Seekings Reference Seekings2008). “The commonly heard lament is that coloured people were not ‘white enough’ under apartheid and are not ‘black enough’ in the new democracy” (Leggett Reference Leggett2004, 21). Thus, “coloured” persons in South Africa have historically been targets of discrimination and exclusion, both before and after apartheid and from both unambiguously “white” and “black” South Africans (Van der Ross Reference Van der Ross2015).

This makes the case of post-apartheid South Africa quite interesting. Formal white supremacy was abolished in 1994 and the police force diversified, resulting in 81 percent of South African police identifying as Black whereas the apartheid-era police were almost exclusively white (Newham, Masuku, and Dlamini Reference Newham, Masuku and Dlamini2006, 11). Nonetheless, ethnoracial disproportion in prisons persisted post this unprecedented national transformation on behalf of racial justice. Data indicates that the “coloured” category is disproportionally at risk of criminal involvement and victimization compared to other South African categories, which may explain their overrepresentation (Thomson Reference Thomson2004). However, given the social history of the “coloured” category, systemic and criminal-justice-specific bias cannot be ruled out as a contributing factor to its disproportionate incarceration, and this potentially diminishes South Africa’s achievement of a racially inclusive democracy.

DISCUSSION

The single-case analyses show prison disproportion occurring under a wide range of conditions, which supports the overall finding that prison disproportion is both extensive and significant among democracies. It may not be surprising that democracies with prominent histories of racial oppression, settler colonialism, and/or stark wealth inequality—such as the United States, Australia, and Brazil—would exhibit disproportionate prison populations, perhaps as a continuation or legacy of historical ethnoracial hierarchy (Davis and Gibson-Light Reference Davis and Gibson-Light2020). However, it may be surprising that prison disproportion extends so significantly beyond the “usual suspects,” even to countries that otherwise could be regarded as criminal justice role models, such as Norway and Germany. So too may it be surprising that prison disproportion is an issue in countries—such as South Africa—where settler-colonizer groups no longer wield direct power over the colonized through the criminal justice apparatus. Space does not permit a fully developed effort to explain why prison disproportion would be so extensive and significant across such a wide range of cases. Indeed, a similar issue arising in various places may have multiple and disparate causes. However, bringing so many cases into view together allows for a consideration of what factors these countries share in common that could be influencing their respective prison demographics such that each has a significantly overrepresented group in its prisons.

Economic Marginalization and Social Exclusion

Among such shared characteristics are, of course, a pattern of inequality: contemporary democracies have generally struggled to overcome their colonial, nationalistic, and/or ethnocraticFootnote 8 roots, resulting in persistent ethnoracial socioeconomic stratification (Jalali and Lipset Reference Jalali, Lipset and Hughey1992; Mann Reference Mann1999). It is proposed that a cycle of social inequality, crime, and punishment produces disproportionate prison populations (Tonry Reference Tonry1997; Western and Pettit Reference Western and Pettit2010). That is, overrepresented groups in prison are observed as similarly overrepresented in committing crimes, which is explained in part by the social stratification that such groups endure. Disproportionate incarceration of statistically disadvantaged groups then reinforces social stratification, and the cycle continues (Sampson and Lauritsen Reference Sampson and Lauritsen1997). Given that none of the cases in the current study could boast a fully inclusive multi-ethnoracial society, conditions for group differentials in offending—as Tonry (Reference Tonry1997) similarly observes—are a common feature among the cases that could account for why it is so difficult to identify a roughly proportional prison population in the sample. Indeed, every overrepresented group identified in the study is also economically marginalized compared to its least incarcerated counterparts, which supports the differential offending thesis.

However, the variation in disproportion across the cases is curious: comparatively extreme disproportion is found in countries where conditions would seem to predict the opposite, such as countries that prior research has identified as having a low “taste” for inequality and its social consequences. While cultural attitudes toward inequality seem connected to overall incarceration rates, as Crutchfield and Pettinicchio (Reference Crutchfield and Pettinicchio2009) and Western and Pettit (Reference Western and Pettit2010) argue, the findings demonstrate that incarceration rates are not a reliable predictor of prison disproportion. Furthermore, prior research has identified numerous groups that are relatively impoverished and yet are not overrepresented in prisons (Tonry Reference Tonry1997, 13–14). An earlier literature proposes that some, but not all, disadvantaged groups are caught up in “cultures of poverty,” bringing them into disproportionate contact with justice systems (Lewis Reference Lewis1966). Were the analysis to end here, we may be left wondering why every country in the sample has an apparent “problem group” filling their prisons despite their cultural and historical variation. Instead, I propose that there is more to consider.

Along with being economically marginalized, the most overrepresented groups in each case are also among the most likely targets of discrimination in their countries. Though perhaps having little else in common, these groups’ respective social histories and present are replete with indicators of negative stereotyping and distrust—when such groups are overrepresented in prisons it is reasonable to consider the role of bias in producing that condition. The question is: how would living under conditions of pervasive discrimination translate into overrepresentation is prison? Further, this must be a somewhat complex process because just as one may identify exceptions to the relationship between economic marginalization and punishment, one can also identify groups that have been subject to historical discrimination and exclusion but that have a limited presence in prison populations. Prominent examples include the various ethnicities within the “Asian” category used similarly by the United States, Brazil, South Africa, New Zealand, and Canada—these either are, or are among, the least incarcerated groups in the sample and yet have demonstrated histories of racial oppression, nonetheless. So, there is a connection between overrepresentation in prison and both economic marginalization and social exclusion, yet not without exception. One way to unravel this complexity may be to shift the focus away from comparing groups and their particular situations and look more closely at justice institutions, especially the police.

Police: Institutionalized Selection Bias?

Democratic societies generally expect that police can and will enforce the law without bias per the principle of equality under law (Sklansky Reference Sklansky2005). Thus, police practices such as ethnic and racial profiling have tended to be widely condemned as incompatible with democratic values (Glaser Reference Glaser2015). Though some degree of bias among police is expected, the proposition that widespread police bias is a significant contributing factor to prison disproportionalities has remained less convincing against more obvious evidence of group differentials in offending and the socioeconomic roots of such disparities (Tonry Reference Tonry1994; Blumstein Reference Blumstein, Bangs and Davis2015). Further, a cross-nationally applicable theory—at least one that identifies specific institutional mechanismsFootnote 9 —has not yet emerged to explain why ethnoracial bias would be pervasive among police within democracies in general despite variation in policing styles,Footnote 10 enforcement priorities, and a wide range of national conditions.

However, what has perhaps been overlooked is that democratic societies tend to tolerate institutional conditions that may engender widespread and routine ethnic and racial profiling. Specifically, an unofficial norm of low police per capita in democracies pressures police to hastily construct suspicion based on nonbehavioral proxies for criminality—such as appearance and incongruity—while navigating “target-rich” urban environments that likely harbor far more crime than small police forces could reasonably hope to interdict. The following proposes analyzing the current study’s findings while recognizing that the heavily outnumbered police who patrol democratic societies are ill-situated to enforce the law equally upon everyone, despite the democratic principle that everyone is equal under law. With this, I offer preliminary reasoning for why differential selection may be a more significant factor in prison disproportion than previous research has concluded.

The average police strength for the sample is 276 officers per 100,000 persons.Footnote 11 This generally low police-to-populace ratio is most obviously because police are expensive (Beaton Reference Beaton1974), yet there is more to this pattern than mere budgetary constraints, or even local politics or crime rates (Stucky Reference Stucky2005). “In democratic societies police power is regarded with enormous suspicion” and thus there is an unspoken upper limit to police strength guided by societal expectations (Bayley Reference Bayley1996, 65). Democratic societies seem to want enough police in society to suggest a basic certainty of state protection but not so many police as to suggest the possibility of active state repression, at least not for the majority (Sung Reference Sung2006). Although police strength may vary in democracies due to political and socioeconomic factors, it seems to remain constrained by public expectations of what a free society should look like.

Such low police-to-total-population ratios may place officers in challenging circumstances: they are surrounded by a diversity of potential crimes and yet not situated to encounter more than a fraction of the crime that may be occurring around them (Reiner Reference Reiner2010). Hence, democratic police necessarily rely on public cooperation to enhance their crime control and community stewardship efforts (Murphy, Hinds, and Fleming Reference Murphy, Hinds and Fleming2008). Yet even enthusiastic public support can only partially compensate for the obvious difficulty of there being, on average, just one officer for every 350 persons: this is simply an overwhelming number of persons to potentially surveil or respond to, especially in fast-moving and complex social environments. And this appreciably paralyzing situation is made even more difficult by expectations that police will interdict criminal behavior that is easily concealed, such as violations involving illicit substances, small arms, and warrants—the existence of such crimes makes anyone, even someone exhibiting little to no indication of criminal wrongdoing, a potential suspect (Wisotsky Reference Wisotsky1992).