INTRODUCTION

Intra-professional status is the socially constructed and accepted ranking of individuals in a profession by the professionals within that profession (Abbott Reference Abbott1981; Washington and Zajac Reference Washington and Zajac2005). Prominent scholars have empirically and theoretically examined intra-professional status in the legal profession (Smigel Reference Smigel1969; Abbott Reference Abbott1981, Reference Abbott1983; Heinz and Laumann Reference Heinz and Laumann1982; Sandefur Reference Sandefur2001). The main thrust of the literature is that there is a prestige ordering of lawyers that can be explained either by the kinds of clients lawyers represent (Heinz and Laumann Reference Heinz and Laumann1982), or the purity of lawyers’ work (Smigel Reference Smigel1969; Abbott Reference Abbott1981, Reference Abbott1983). In either case, lawyers are ascribed different levels of status.

Similar to the ranking of individuals in a profession, intra-organizational status is the ranking of individuals in an organization (Waldron Reference Waldron1998). Scholars have examined intra-organizational status in the context of law firm partnership levels and how engaging in pro bono work might raise the status of a law firm lawyer (Kay and Gorman Reference Kay and Elizabeth2008; Dinovitzer and Garth Reference Dinovitzer, Bryant, Granfield and Mather2009). Scholars have also examined how gender inequality shapes women’s experiences in large law firms (Dinovitzer and Garth Reference Dinovitzer, Bryant, Granfield and Mather2009; Rhode Reference Rhode2011; Walsh Reference Walsh2012; Sterling and Reichman Reference Sterling and Reichman2013; Deo Reference Deo2019).

Starting in the early 2000s when American Lawyer Media pro bono rankings became the standard for the appropriate level of pro bono work law firms ought to undertake, large law firms began to hire lawyers to manage their pro bono programs to increase their rankings and public image (Cummings Reference Cummings2004). The limited research on pro bono professionals developed often without much differentiation between the experiences of lawyers who manage pro bono programs, and others who are not lawyers and occupy similar roles (see Cummings Reference Cummings2004; Boutcher Reference Boutcher2010). I am aware of only one study that differentiates between lawyers and other professionals in these roles (Cummings and Rhode Reference Cummings and Rhode2010).Footnote 1 However, even that study does not theorize about the status of lawyers who manage pro bono programs vis-à-vis other lawyers in law firms.

Yet there are important considerations for lawyers who manage pro bono programs in large law firms. One consideration is how their organizational status impacts their work as managers of pro bono programs and their identities as lawyers. Both intra-professional and intra-organizational statuses are useful for conceptualizing these experiences. The perceived status of pro bono partners and counsels can influence the legitimacy of pro bono work within a law firm and potentially impact the quantity and quality of law firm pro bono work. Moreover, since research has demonstrated gender inequality in other law firm contexts—associate retention, promotion to partner—understanding how the experiences of pro bono partners and counsels might differ based on gender is an important addition to the literature.

This article therefore attempts to reconcile the literature on intra-professional status, intra-organizational status, and gender inequality in the legal profession—with particular emphasis on the large law firm—by examining the process by which pro bono partners and counsels (a subgroup of the legal profession) navigate and negotiate their status as lawyers in law firms (organizational context) and how gender disparities might shape their experiences. Using original demographic data from all 137 pro bono partners and counsels interspersed across the top one hundred law firms in the United States based on American Lawyer Media rankings and interviews from thirty-nine pro bono partners and counsels who manage pro bono programs in thirty-five of those law firms, I show how pro bono partners and counsels navigate their status as law firm lawyers and managers and how gender inequality influences their experiences.

To situate status in the organizational context, I first survey the literature on law firm pro bono work, intra-professional status from the perspective of the client type and professionalpurity theories, and intra-organizational status. I then review the literature on gender inequality in the legal profession, including in law firms. In the methods section, I explain the demographic and interview data in the study. In the findings section, I first provide a background on pro bono partners and counsels. I then show how pro bono partners and counsels navigate their ambiguous roles as lawyers, administrators, and managers by striving to be perceived as real lawyers, reframing their roles as business generators, conforming to the culture of billing time, and establishing a common identity through the Association of Pro Bono Counsel (APBCO). They also negotiate their titles and office spaces, which are markers of status in large law firms. Women are more likely than men to occupy what would be considered lower status office spaces.

I find that, despite the fact that men and women pro bono partners and counsels are similar in terms of their interests in public interest law, tiers of law schools attended, prior legal practice settings, and prior substantive areas of law practiced, gender nevertheless influences their experiences in three particular ways. First, men are more likely to be pro bono partners, although the difference is not statistically significant. Second, men and women differ in their current substantive areas of law, and the difference is statistically significant. Men are more likely to focus their practice on impact litigation, criminal representation, or multiple areas of practice, while women are more likely to focus on family law, immigration law, human rights, or not practice law at all. A possible theory for this distinction is that men strategically self-select into high-status practice areas once they assume their positions because firms ascribe differing levels of prestige to different areas of law, such as impact litigation versus family law or death penalty versus human trafficking. Third, lawyers that do not practice law at all are overwhelmingly female and are often designated as staff rather than lawyers in their law firms, even though they may carry the counsel title externally. Lawyers who are staff rather than lawyers internally are more likely to lack professional autonomy in the approval of pro bono matters—an important role of the pro bono partner or counsel—than those who are considered lawyers both internally and outside their law firms.

These findings deepen our understanding of law firm status hierarchies and potential impediments to pro bono participation. The findings also have implications for the legitimacy of pro bono work in law firms.

LAW FIRM PRO BONO

The legal profession has historically been committed to furthering the public interest alongside profitability (Nelson Reference Nelson1988). This is also true for the large law firm through its engagement in pro bono work and financial support for public interest legal organizations (Nelson Reference Nelson1988; Cummings Reference Cummings2004; Cummings and Rhode Reference Cummings and Rhode2010; Adediran Reference Adediran2020b). As pro bono work became institutionalized in large law firms, firms began to hire coordinators, legal secretaries, and specialists—who were often not lawyers—to manage their pro bono programs (Cummings Reference Cummings2004). Institutionalization means that pro bono work became “interwoven into the basic fabric of the [firm], where it is governed by explicit rules, identifiable practices, and implicit norms promoting public service” (Cummings and Rhode Reference Cummings and Rhode2010, 2364).

As a response to the institutionalization of pro bono work in law firms, scholarship on law firm pro bono developed around two broad issues. The first is scholarship on law firms’ motivations for expending resources on pro bono work (Strossen Reference Strossen1993; Rhee Reference Rhee1996; Justus Reference Justus2003; Rhode Reference Rhode2005a, 2005b, 2009; Daniels and Martin Reference Daniels, Joanne and Rebecca2009). Research indicates that large firms sought to increase their public image for the benefit of recruiting and retaining lawyers (Galanter and Palay Reference Galanter, Thomas and Robert1995; Lardent Reference Lardent and Robert1995; Pistor Reference Pistor2020). Organizations such as the National Association for Law Placement (NALP) and media outlets, such as American Lawyer and the National Law Journal, began ranking law firms based on their pro bono performance, resulting in firms internally taking pro bono work more seriously to improve their public image (Lardent Reference Lardent and Robert1995; Cummings Reference Cummings2004). Firms began tracking their pro bono activities, creating pro bono budgets and marketing pro bono work as part of their recruiting and retention efforts (Cummings Reference Cummings2004; Carnahan, Kryscynski, and Olson Reference Carnahan, David and Daniel2016). Law schools and law students, in turn, began requesting pro bono information from firms, and firms responded by including information on pro bono in their marketing publications available to law students (Lardent Reference Lardent and Robert1995). Training and career development opportunities for new lawyers in firms was another reason for this development (Cummings and Rhode Reference Cummings and Rhode2010).

Corporate clients also have a major influence on law firm policies (Adediran Reference Adediran2018). Many corporate chief executive officers perceive pro bono work as a form of corporate social responsibility (Lardent Reference Lardent and Robert1995; Justus Reference Justus2003). Some corporate clients specifically began asking law firms about their pro bono efforts and responded favorably to strong emphasis on pro bono work. Starting as early as 1993, corporate legal departments began partnering with firms to tackle specific legal issues or projects, including by creating legal clinics. These partnerships encouraged law firms to further invest in pro bono programs (Lardent Reference Lardent and Robert1995). Starting in the early 2000s, large law firms began to hire lawyers to improve their pro bono programs, rankings, and image of public service (Cummings Reference Cummings2004).

The second strand of pro bono scholarship is on how institutional impediments, including policies and internal culture, impact the value and implementation of pro bono work in law firms (Scheingold and Bloom Reference Scheingold and Anne1998; Rhode Reference Rhode2005a; Daniels and Martin Reference Daniels, Joanne and Rebecca2009; Adediran Reference Adediran2020a). However, there has been limited research on the professionals that manage pro bono work in law firms as the key subject of inquiry. The limited research on pro bono managers in law firms developed often without much differentiation between the experiences of lawyers who manage pro bono programs and others who occupy similar roles (see Cummings Reference Cummings2004; Boutcher Reference Boutcher2010; Cummings and Rhode Reference Cummings and Rhode2010). This article begins to address this gap in the literature by focusing on the status of the professionals who manage pro bono programs at the most elite law firms.

INTRA-PROFESSIONAL STATUS: CLIENT TYPE AND PROFESSIONAL PURITY

Intra-professional status is the status of “a subgroup within a profession in the eyes of other members of the same profession” (Abbott Reference Abbott1983, 858). It is a quality of professional honor assigned groups within a profession by the professionals themselves (Abbott Reference Abbott1981). In the legal profession, two theories have developed to explain the distribution of professional status (Sandefur Reference Sandefur2001). The first theory is the client-type theory, which states that the kinds of clients that lawyers represent determine their status (Heinz and Laumann Reference Heinz and Laumann1982). The second theory is the concept of professional purity, which is the idea that role ambiguity can lower one’s status within the profession (Abbott Reference Abbott1981).

The client-type theory posits that a professional’s status is influenced by the status of the entities with whom the professional affiliates. John Heinz and Edward Laumann (Reference Heinz and Laumann1982) are the main proponents of the client-type theory in the legal profession (see also Laumann and Heinz Reference Laumann and Heinz1977). From their study of lawyers in Chicago, they concluded that prestige in the legal profession is determined by the kinds of clients that lawyers represent (Heinz and Laumann Reference Heinz and Laumann1982). They found that lawyers who represent corporate clients in matters like securities and patents often specialize in narrow ranges of legal fields even if their law firms represent clients with a myriad of legal issues (Heinz and Laumann Reference Heinz and Laumann1982; Abbott Reference Abbott1988). They are also more likely to have decision-making power on the allocation of scarce resources and in the determination of social outcomes. Lawyers who represent corporate clients are ascribed higher status in the profession than lawyers who represent individuals in legal matters such as evictions, immigration, or divorces (Heinz and Laumann Reference Heinz and Laumann1982). Lawyers who represent corporate clients are also more likely to work in high-status workplaces, such as in elite law firms (Nelson Reference Nelson1985; Abbott Reference Abbott1988).

Lawyers who represent individuals often do so as solo practitioners or in small general practices serving clients on personal and small business matters. Lawyers who represent individuals are more likely to be generalists and engage in a range of legal issues, including family, immigration, real estate, and eviction law (Heinz and Laumann Reference Heinz and Laumann1982). Laumann and Heinz (Reference Laumann and Heinz1977) also considered the role of altruistic work—specifically, pro bono work—on intra-professional status in the legal profession. They examined how work in an area of law—like securities, patents, or family law—influenced the degree to which lawyers tended to work pro bono, or for altruistic motives, rather than primarily by a desire for profit. They found that the higher a specialty stood in its reputation for being motivated by altruistic, rather than profitable, considerations, the lower it was likely to be on the prestige order in the legal profession (Laumann and Heinz Reference Laumann and Heinz1977; Abbott Reference Abbott1988).

Andrew Abbott (Reference Abbott1981, Reference Abbott1983, Reference Abbott1988) has produced some of the seminal scholarship on professional purity. Professional purity is the ability to exclude nonprofessional or irrelevant professional issues from practice. Within a given profession, the highest-status professionals are those who deal with issues that are more professionally defined, clear, and unambiguous (Abbott Reference Abbott1981). The theory is that a profession is organized around the knowledge system it applies and that status within the profession would simply reflect the degree of involvement with this organizing knowledge. The more a professional’s work employs that knowledge alone—the more it excludes extraneous factors—the more the professional enjoys a high status (Abbott Reference Abbott1988).

In the legal profession, undefined roles, including combining administrative roles with the practice of law has been found to establish professional impurity (Smigel Reference Smigel1964b). Erwin Smigel (Reference Smigel1964b, 238) provides a useful illustration with his example of the role of the law firm managing partner in the 1960s. He found that, as the role of the managing partner became more administrative in nature, the position became less prestigious and was less likely to attract important personalities. Smigel found that the role lost status as the amount of time needed for administrative duties had to be taken from the practice of corporate law. Many managing partners wanted to return to full-time practice that did not include administrative tasks.

In sum, intra-professional status in the legal profession is influenced by lawyers’ affiliations with their clients—the more specialized and corporate, the more status a lawyer enjoys. Intra-professional status is also influenced by altruism. Practice settings that are more likely to be motivated by altruism rather than profit tend to have a lower status. Finally, professional purity—legal practice that excludes extraneous roles—is akin to high status in the legal profession.

INTRA-ORGANIZATIONAL STATUS

Intra-organizational status is the ordering of individuals within an organization (Waldron Reference Waldron1998). Status rankings in organizations shape how members interact with each other (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Berger, Cohen and Zelditch1966). Status rankings also shape the resources an individual can marshal within an organization (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Peterson, Phillips, Podolny and Ridgeway2012). An individual can achieve organizational status by signaling high performance (Waldron Reference Waldron1998). In organizations like large law firms, achieving partnership—especially equity partnership—is often an indicator of high performance and status (Kay and Gorman Reference Kay and Elizabeth2008). This means that fee-charging partners who have a high status in the legal profession also often have a high status within their law firms (Galanter and Palay Reference Galanter, Thomas, Robert, Trubek and Rayman1992). The law firm setting—wealthy and corporate clients, large market shares, high incomes—also bestows a high status on large law firm partners in other areas of the legal profession (Abel Reference Abel1989; Galanter and Palay Reference Galanter, Thomas, Robert, Trubek and Rayman1992).

Indeed, while altruism and pro bono work tend to be indicators of lower status in the legal profession, the large law firm setting can be exceptional. Corporate lawyers in the largest firms are more likely to engage in pro bono work than lawyers in other settings and also enjoy the highest status in the profession. Engaging in pro bono work in large law firms does not lower status for some corporate lawyers and can even elevate it (Dinovitzer and Garth Reference Dinovitzer, Bryant, Granfield and Mather2009). However, not all pro bono work is created equal; some forms of pro bono work provide more prestige than others (Garth Reference Garth2004; Dinovitzer and Garth Reference Dinovitzer, Bryant, Granfield and Mather2009). In addition, high prestige pro bono work is not equally available to all lawyers, and, thus, pro bono cannot equally bring prestige to all lawyers (Dinovitzer and Garth Reference Dinovitzer, Bryant, Granfield and Mather2009). Equity partners, who already enjoy high status, will likely have access to the most prestigious pro bono work.

GENDER INEQUALITY AND STRATIFICATION IN THE LEGAL PROFESSION

Despite the mass entry of women into the legal profession, gender inequality persists; lawyers are stratified into different status groups based on gender (Payne-Pikus, Hagan, and Nelson Reference Payne-Pikus, John and Nelson2010; Muzio and Tomlinson 2012; Pearce, Wald, and Ballakrishnen Reference Pearce, Eli and Ballakrishnen2014). This stratification is visible across the legal profession. Research has shown that female lawyers in the United States earn less than their male counterparts, controlling for factors such as the number of years in practice, rank, and billable hours (Dinovitzer, Reichman, and Sterling Reference Dinovitzer, Bryant, Granfield and Mather2009; Sterling and Reichman Reference Sterling and Reichman2013; Triedman Reference Triedman2015). Women are also more likely to leave the practice of law than men (Sterling and Reichman Reference Sterling and Reichman2013; Triedman Reference Triedman2015). Attrition rates are almost twice as high among female associates as among comparable male associates in law firms (Rhode Reference Rhode2011).

In 2020, women represented 47 percent of associates and only 25 percent of all partners in law firms. Black and Latinx women each still accounted for less than 1 percent of all partners, at 0.80 percent and 0.90 percent respectively (NALP 2021). Equity partners have high status, earn the highest compensation in firms, enjoy some job security, have extensive autonomy in their work, and participate in governance and decision-making (Kay and Gorman Reference Kay and Elizabeth2008; Epstein and Kolker Reference Epstein and Abigail2013). Non-equity partnership is a lower tier with fewer of the benefits that equity partners enjoy (Richmond Reference Richmond2010). Research has shown that women are less likely to become equity partners in law firms, even controlling for factors such as law school grades, part-time schedules, and aspirations to make partner (Kay and Gorman Reference Kay and Elizabeth2008; Dinovitzer, Reichman, and Sterling Reference Dinovitzer, Bryant, Granfield and Mather2009; Rhode Reference Rhode2011; Walsh Reference Walsh2012; Dinovitzer and Garth Reference Dinovitzer and Bryant2020). In 2020, women comprised only about 21 percent of all equity partners in law firms. For women of color, that number was less than 4 percent (NALP 2021).

The problem is not limited to the large law firm. In legal academia, women continue to be underrepresented (Chamallas Reference Chamallas2005; Barnes and Mertz Reference Barnes and Elizabeth2012; Pearce, Wald, and Ballakrishnen Reference Pearce, Wald and Ballakrishnen2015; Deo Reference Deo2015, Reference Deo2019). Women are also more likely to occupy low-status non-tenured positions as librarians, clinicians, and legal research and writing instructors (Czapanskiy and Singer Reference Czapanskiy and Singer1988; Angel Reference Angel2000; Kornhauser Reference Kornhauser2004). Even for women in tenure and tenure-track positions, gender inequality persists in a variety of forms (Winslow and Davis Reference Winslow and Davis2016). Women are significantly more likely to be interested in, enter, and remain in the public interest law sector, endorse the value of doing pro bono work, and engage in more hours of pro bono work than men (Granfield Reference Granfield2007; Dinovitzer and Garth Reference Dinovitzer, Bryant, Granfield and Mather2009; Albiston, Cummings, and Abel Reference Albiston, Cummings and Abel2021). If engaging in pro bono work is an indicator of lower status, then engaging in more pro bono work than their male counterparts may exacerbate gender inequality. Therefore, while women have made significant strides in the legal profession, they are less likely to occupy high-status positions. At the same time, women are more likely to join and remain in the public interest law sector or engage in more pro bono work than men.

DATA AND METHODS

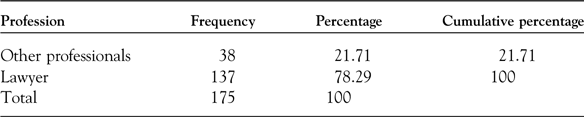

This study uses two types of data. The first are original demographic data of all 137 pro bono partners and counsels in Am Law 100 firms. I took several steps to generate this novel data. I first compiled a list of all pro bono managers, coordinators, specialists, partners, counsels, directors, and fellows in every Am Law 100 firm using Vault’s Guide to Law Firm Pro Bono Programs and American Lawyer rankings. 175 individuals met these criteria as shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1. Distribution of lawyer/Other professional

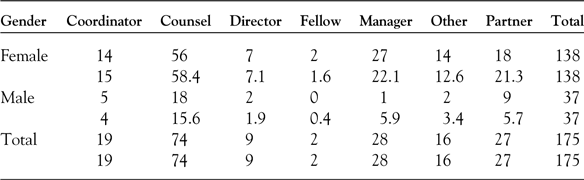

Next, I searched each individual’s law firm website to code key demographic information including gender, race or ethnicity, title, and education (whether they earned a JD or not and whether they attended a US News top 14 law school). I omitted individuals who did not complete a JD degree from the sample to arrive at the 137 lawyers in the study. These 137 lawyers have varied titles: partner, counsel, special counsel, director, manager, and fellow. There are only five special counsels, so I collapsed the group into the counsel group. Fellows are new lawyers that law firms hire to exclusively represent pro bono clients. In this sense, they are similar to junior associates except that they do not represent fee-charging clients. The role is often temporary and does not involve pro bono management. As such, I have included fellows in Table 2 only for completeness, but they are not part of the status analysis. Only fourteen of the 137 lawyers have manager titles, and only one lawyer has a coordinator title. Not every Am Law 100 firm has a full-time lawyer in a pro bono management role. As such, the 137 lawyers manage national and international pro bono practices across several offices in seventy-two Am Law 100 firms. Thirty-four of the seventy-two firms have between two and seven full-time pro bono partners and counsels. The remaining thirty-eight have only one lawyer in the role.

TABLE 2. Titles

Notes:

In each cell, the upper value is observed frequency and the lower number is the expected frequency. Pearson chi 2(6) = 9.6054; p = 0.142.

I limited the data for pro bono partners and counsels to only Am Law 100 firms because firms outside of the Am Law 100 are generally less likely to hire full-time pro bono partners and counsels. I relied on law firm websites, blogs, newsletters, social media platforms, including LinkedIn and Facebook, to code individual demographic information.

The second source of data included thirty-nine interviews of pro bono partners and counsels across thirty-two large firms that I conducted in 2017 and 2020. My interview sample represents 44 percent of the larger population of law firms that have hired lawyers to manage their pro bono programs and reached saturation. In qualitative social science research, saturation is a marker of rigor and occurs when a researcher no longer derives new information or themes from participants (Guest, Bunce, and Johnson Reference Guest, Arwen and Laura2006; Onwuegbuzie and Leech Reference Onwuegbuzie and Leech2007).

Thirteen of the thirty-nine lawyers in the interview sample are partners. Since there are only twenty-seven partners in the entire universe of pro bono partners and counsels in Am Law 100 firms, the thirteen partners represent 48 percent of all pro bono partners in large firms. Oversampling partners allows me to make conclusions about the pro bono partner population, which is otherwise small. Three interview participants are directors, and twenty-three are counsels. Thirty-two of the thirty-nine interviews were conducted in person, while seven were conducted via zoom. The participants were located in the Northeast (20), Midwest (10), South (5), and West (4). Not surprisingly, the highest numbers of participants were in the Northeast, since most Am Law 100 firms have their largest offices in the Northeast in cities like New York and Washington, DC, where pro bono partners and counsels tend to be physically located.

The interviews lasted between sixty and 120 minutes. Interviews were semi-structured (Berg Reference Berg2001). The in-depth nature of the interviews allowed me to build rapport and trust with participants (Greene Reference Greene2016). To recruit participants, I used both convenience and snowball sampling (Weiss Reference Weiss1995). I first sent an email to every pro bono partner, director, counsel, or manager across the United States. About fourteen individuals initially agreed to participate in the study. Next, I attended the March 2017 Equal Justice Conference (EJC) to personally recruit participants. The EJC—co-sponsored by the American Bar Association’s Standing Committee on Pro Bono and Public Service and the National Legal Aid and Defender Association—is an annual gathering of groups concerned with access to justice, including law firm pro bono partners and counsels, members of public interest legal organizations, corporate counsel, judges and funders. From the conference, I recruited another twelve pro bono partners and counsels. The remaining thirteen participants joined the study through referrals from other participants.

During the interviews, I asked participants open-ended questions, including about their day-to-day activities, their career paths to becoming pro bono partners and counsels, how they conduct their work, whether and how they report their work, questions around the level of discretion and autonomy they enjoy, and their experiences with APBCO. For the thirty-two in-person interviews, I also observed workspaces and asked questions about their office spaces in relation to their law firm positions. Questions about their workspaces allowed me to make conclusions about the relationship between space and status in law firms.

I used the grounded theory method of data analysis, which means that my findings were discovered, developed, and provisionally verified through systematic data collection and analysis (Strauss Reference Strauss and Corbin1990). The patterns, themes, and categories of analysis came from the data rather than being imposed on the data prior to collection and analysis (Patton Reference Patton1990). Using text management software (ATLAS.ti), I manually coded all interviews for common and reoccurring themes using a code list created and continually developed during and after data collection. In accordance with the requirements of the Institutional Review Board and the confidentiality agreement signed by the participants and myself, I have made every effort to protect participants and their organizations’ identities. Each participant was assigned a unique identification number included on transcripts and data files.

BACKGROUND

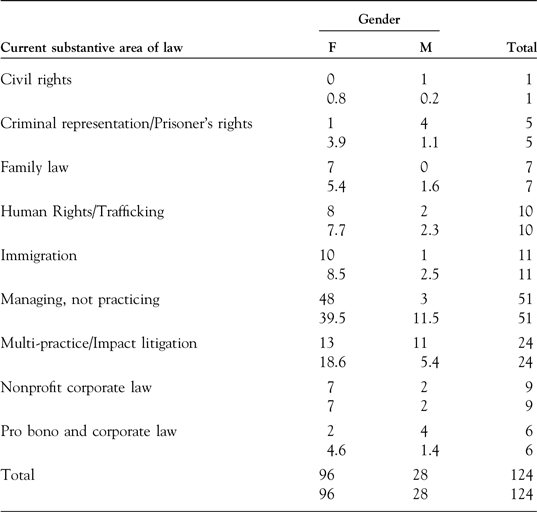

To contextualize my analysis, I begin with demographic information and other discussion of the lawyers that occupy the role of pro bono partners and counsels in large law firms. In this article, a pro bono partner or counsel is a lawyer in charge of the full-time management of the global pro bono program of a top 100 law firm in the United States ranked by American Lawyer. Pro bono partners and counsels are authorized to practice law by their state bars, and most of them practice law. As shown on Table 3, which I generated with publicly available data and interviews, those who currently practice law focus on a variety of substantive areas, such as immigration law (including asylum and refugee law), family law (including domestic violence), criminal representation and prisoner’s rights, human rights law (including trafficking), civil rights, and nonprofit corporate law. A small handful of the lawyers are true generalists with expertise and practice in two or more areas of law or exclusively engaged in impact litigation in a variety of areas. Only six currently practice part-time in a fee-charging corporate practice (4 percent).

TABLE 3. Current substantive area of law by gender

Notes:

In each cell, the upper value is the observed frequency and the lower number is the expected frequency. Pearson chi 2(8) = 38.31; p = 0.000.

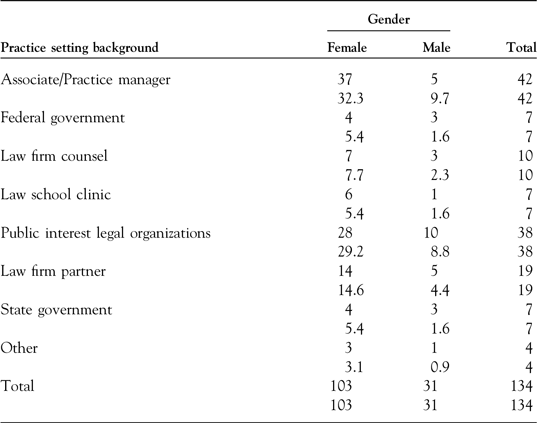

As shown on Table 4, prior to their full-time roles managing pro bono programs, these lawyers practiced in law firms as fee-charging partners and associates, in public interest legal organizations as staff attorneys or directors, in state and federal government, and as directors of law school clinics. Most—58 percent—were either law firm associates or practice managers or lawyers in public interest legal organizations. These lawyers practiced commercial litigation, criminal law, impact litigation, low-income legal services, and counseled and represented state and federal governments. Some had a variety of practice experiences combining two or more of these fields. Table 5 provides a distribution of practice backgrounds by gender. I generated the table through interview and publicly available data.

TABLE 4. Practice setting prior to position by gender

Notes:

In each cell, the upper value is the observed frequency and the lower number is the expected frequency. Pearson chi 2(6) = 6.9465; p = 0.434.

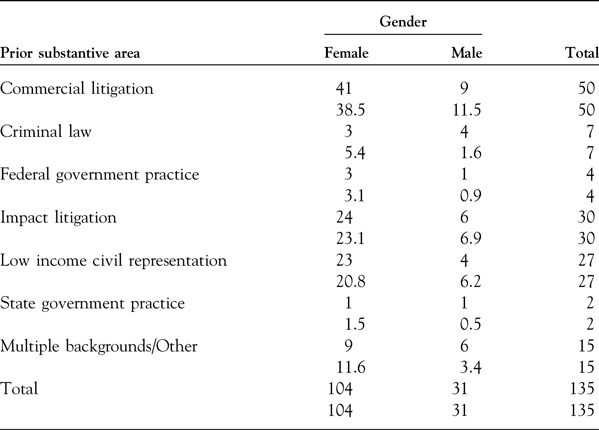

TABLE 5. Prior substantive area of law by gender

Notes:

In each cell, the upper value is the observed frequency and the lower number is the expected frequency. Pearson chi 2(6) = 9.7783; p = 0.134.

Pro bono partners and counsels who currently practice law generally devote between 5 percent and 60 percent of their time providing individual representation to low-income clients or engaging in litigation, law reform, or nonprofit corporate representation. The rest of their work is focused on the full-time management and administration of their law firm’s global pro bono programs. Regardless of gender, the typical pro bono partner or counsel has a strong public interest background either in the private, government or nonprofit sectors. Like the larger population, all thirty-nine pro bono partners and counsels in the interview study either began their careers in large law firms as associates and carefully chose law firms that they perceived to be pro bono friendly or began in public interest legal organizations as fellows or staff attorneys. Indeed, the typical pro bono partner or counsel generally has little to no interest in long term corporate practice. As such, both intra-professional status—particularly, the client-type theory—and intra-organizational status can explain the lower status of pro bono partners and counsels based on these backgrounds. Specifically, as lawyers that formerly represented low-income and other vulnerable and underserved clients in nonprofits, and as former law firm associates who are considered lower status than law firm partners, pro bono partners and counsels enter their positions already susceptible to both lower intra-professional and intra-organizational status.

A male pro bono partner described himself as someone who has “always been interested in public interest legal work. I worked in the legal aid clinic when I was in law school. [] I went to [firm] specifically because they were renowned for their pro bono work. I left [firm] because … I can’t spend that many hours on things I care that little about.” Another male pro bono counsel described his experience as a former “associate at a large firm. … I woke up realizing that one day I was going to kick it, and on my tombstone, it was going to say: defended The Man in discrimination lawsuits. That just wasn’t me. … I wanted to make the switch to public interest to manage a nonprofit.”

A female pro bono partner described a similar trajectory: “I considered going directly into legal services work, but believed that I would get some good training at a law firm and also to help pay off the debt, which was significant. So, I decided to come to a firm, but only considered firms that had strong pro bono programs, and I got involved in pro bono right from the beginning.” Another female pro bono counsel described her strong interest in public interest law prior to graduating from law school: “I actually didn’t apply to any firms when I was graduating. I didn’t go on [on campus interviewing]. I didn’t go through any of that process. Then I got a one-year [public interest] fellowship.”

Therefore, pro bono partners and counsels—regardless of gender—have strong interests and backgrounds in public interest law and choose to become pro bono partners and counsels largely because of this interest.

The law firm pro bono partner and counsel position emerged in the late 1980s and early 1990s when a small number of lawyers began to make direct proposals to law firms to establish these positions (Cummings and Rhode Reference Cummings and Rhode2010). Proposals to create these positions varied widely since each potential pro bono partner or counsel pitched the role to specific firms depending on the firms’ interests and needs. In the early stages, most positions were part-time because there was some reluctance to hire lawyers into these roles. A pro bono partner explained how he created his position in the 1990s first as a part-time role:

I went around to twenty law firms in town, and I said, I’ll make you a deal. I’ll give you two-thirds of the number of billable hours that you expect from one of your litigation associates, you pay me two-thirds the usual salary, and let me set aside one-third of my time for pro bono work … which I thought made perfect economic sense.

A pro bono director had left a law firm and “wrote up a proposal to come back and create this job” in the early 2000s. Prior to the firm hiring a lawyer, there was “a [] pro bono coordinator who had been here for about ten years.”

Firms also directly contacted individuals they thought would fit the newly created position. For instance, a pro bono counsel explained how he got called to make a proposal for his position in the 1990s: “[A] partner here, head of the pro bono committee, called me out of the blue and said, we want to combine pro bono and training, and I think you would be a perfect person.” As the role diffused across firms and became permanent, lawyers no longer needed to convince law firms to hire them. Similar to diversity, sustainability, and corporate social responsibility managers, pro bono partners and counsels can now be thought of as an emerging occupation within the legal profession (Kelly and Dobbin Reference Kelly and Frank1998; Lounsbury Reference Lounsbury1998b; Dobbin, Kalev, and Kelly Reference Dobbin, Kalev and Kelly2007; Risi and Wickert Reference Risi and Christopher2017).

Today, pro bono partners and counsels in law firms are engaged in the following roles: connecting their firms to pro bono opportunities in public interest legal organizations, approving pro bono matters that firms ultimately adopt, supervising associates, reviewing work product, providing consultation and advice to partners and associates—especially when the pro bono partner or counsel has expertise in a substantive area of law—and representing low-income clients or engaging in legal advocacy pro bono. When they engage in pro bono work, pro bono partners and counsels provide direct legal services and/or impact litigation. Many develop expertise in broad areas of law. For example, a pro bono partner spoke about his expertise in immigration law: “I’m a supervising partner on a number of immigration matters, because I used to be an immigration lawyer. So, in some respects, I know more than a lot of people here about the subject.” Table 3 indicates the broad areas of practice on which these lawyers focus. Finally, while some pro bono partners and counsels have superiors in similar roles, many do not. Not having a pro bono superior means that a pro bono partner or counsel occupies the highest ranked position for that role in a particular law firm.

NEGOTIATING INTRA-PROFESSIONAL AND INTRA-ORGANIZATIONAL STATUS

In the sections that follow, I show how pro bono partners and counsels negotiate role ambiguity by striving to be perceived as “real lawyers,” reframing their roles as business generators, conforming to the culture of billing time, and establishing a common identity through APBCO. I also show how they negotiate their titles and office spaces as lawyers. These negotiations mainly occur in the large firm setting, except for the common organizational identity process, which is a joint external effort among pro bono partners, counsels, and other pro bono professionals who are not lawyers. It is important to note that, while pro bono partners and counsels may struggle with their status as lawyers in the law firm context, the high status of their elite firms likely provides them with high status outside of the law firm context. For example, even though a pro bono counsel may have low status among lawyers in her law firm, she may be considered high status by other members of the legal profession by virtue of her relatively high income or the elite status of her law firm (see Abbott Reference Abbott1981).

Navigating Role Ambiguity

Ambiguity is central to the role of pro bono partners and counsels in large law firms. Generally, pro bono partners and counsels combine law practice with myriad administrative roles. They typically devote between 5 percent and 60 percent of their time to legal practice at any given time. Although only about 20 percent of them are partners, pro bono partners and counsels serve the dual role of lawyers, managers, and administrators. Traditionally, large law firms are structured as partnerships and managed by partners. A partnership is a legal and economic structure exemplifying principles of mutual obligation and an equal right to share profits and debts (Nelson Reference Nelson1988). Partners manage legal teams of lawyers that are comprised mostly of associates who do not share in profits and losses (Samuelson Reference Samuelson1990). Pro bono partners and counsels also manage legal teams of associates but struggle with being perceived as “real lawyers.”

Being Perceived as a “Real Lawyer”

To maintain their identities as lawyers, pro bono partners and counsels strive to be perceived as “real lawyers” in their law firms. While the client-type theory of intra-professional status might suggest that providing legal services to pro bono clients is congruent with a low status, pro bono partners and counsels provide legal representation to individual clients or impact litigation to maintain their identities as lawyers and boost their status. The data does not suggest that there are particular types of matters that pro bono partners and counsels pursue to achieve the goal of being perceived as “real lawyers”; simply representing clients or causes is enough. Table 3 shows a range of legal areas that pro bono partners and counsels currently pursue and develop expertise in. The choice of pro bono areas is largely based on individual interests. This is consistent with prior research that shows that while law firms may be motivated to choose high-profile pro bono matters (Adediran Reference Adediran2020a, Reference Adediran2020b), and, as shown below, male pro bono partners and counsels may also be motivated to choose high-profile matters, individual lawyers in law firms ultimately choose their pro bono matters. Part of the role of pro bono partners and counsels is to strive to provide lawyers with the kinds of pro bono matters they choose to engage. Like other lawyers in their firms, pro bono partners and counsels also choose their matters based on interest.

A pro bono partner talked about the importance of continuing to practice law as a “real lawyer”:

From the day I started this, I said I want to be able to continue to practice law. … I think it also has to do with how I’m viewed within the firm. It has always been very important to me that the lawyers that I work with recognize me as a real lawyer, and I think part of being a real lawyer is doing real legal work. And so, when I do a successful amicus brief in a court of appeals, or whatever, I think that enhances my standing with the colleagues that I’m asking to do pro bono work.

Another pro bono partner explained the importance of continuing to engage in legal work: “It’s important for me to at least do some kind of actual legal work because I have to constantly be reminded of how important these issues are and what impact legal representation has. I don’t consider myself just an administrator.” Another pro bono partner similarly described how practicing law is part of his identity as a person and is therefore a non-negotiable part of his role:

I take a lot of pride in being able to do legal work and having expertise in certain areas, and I cannot imagine not practicing. … I love running our pro bono [] program, I love the recruiting part of it, I love even giving presentations to the new associates and the summer associates, but I think for my own sense of myself as a lawyer, [and] it’s [also] important for the attorneys in the firm to know that I practice as well [rather than] … just me sitting in an office and giving presentations and doing just administrative stuff as opposed to really knowing what they’re going through.

Therefore, pro bono partners and counsels strive to be perceived as “real lawyers” by continuing to practice law, which is important to their identities as lawyers and persons.

Reframing Role as Business Generators

In the large law firm setting, business generation is part of the role of high-status fee-charging equity partners (Nelson Reference Nelson1988; Galanter and Palay Reference Galanter, Thomas and Robert1995). In negotiating their status, pro bono partners and counsels have chosen to adapt to the profit-making logics of law firms by reframing their roles as business-generating partners between corporate clients and their firms by taking advantage of the increasing interest of corporate clients in collaborating with law firms to provide pro bono work (Rhode, Ricca, and Winn Reference Rhode, Lucy and Micheal2020). A pro bono counsel explained:

More corporate departments are considering having a designated person to manage their pro bono program and having a more developed pro bono program. And they’re actually reaching out to firms to say, you have a pro bono program, how did you get it set up, how is yours structured. Because they are considering having [] their own pro bono person. And we have more corporate counsel asking to join APBCO because they’re managing the pro bono program at their corporate in-house department.

Fifteen pro bono partners and counsels described their roles as business-generating partners with corporate clients. For example, a pro bono counsel described her role in crafting an in-house counsel’s pro bono program:

You probably heard of that trend [of] billable clients … want [sic] to do pro bono work and they don’t have anybody with our role [] and so that is a huge part of their time. The meeting I have at 11:45 is a training that we’re hosting with lawyers from one of our billable clients. They want to come in. They’re going to get trained. We are hosting a clinic in a couple of weeks so the [pro bono] clients will come here.

Pro bono partners and counsels use this interest to raise their profiles in their law firms. A pro bono counsel remarked: “[A]nother component of what I do is work with our corporate clients. So, a lot of our corporate clients, corporations, have legal departments, and they want to do pro bono, so increasingly, I’m spending time working with them.” A pro bono partner considers her role to be similar to her fee-charging colleagues in relation to corporate clients:

The biggest difference is I don’t have corporate clients that I’m doing billable work for. That’s kind of obvious. I do though, however, have many relationships with corporate clients because we partner with them on pro bono matters. So, it’s less different than you might think because I am still client-facing in that sense. You know, similarities between billable partners and me are just, you know, managing matters, managing a practice, supervising people.

A pro bono counsel explained it in terms of generating profit for the firm:

In some ways you’re totally undervalued, because they think of me as a cost center probably, even though I’m not a cost center. Because I do a lot of work with our corporate clients, for instance. And, I think I add a lot of value in terms of you see now more [requests for proposals] and things like that asking about pro bono. So, if we’re making a pitch to a paying client, they’ll ask about our pro bono program. So, I think there’s a lot of value added by our pro bono program to our billable matters. But, it’s not always as transparent as a big bill that gets billed by a payable client.

Another pro bono partner described how large corporations recruit fee-charging partners for billable work through their pro bono relationships:

[With] pro bono you can do multiple things at once. You can do personal development, and professional development, and quality of life, and all of that other stuff, not to mention helping people. Because the Google team asked you to do it.

While carving out a business-generating role legitimizes the pro bono partner or counsel’s role as a real lawyer and, in the case of partners, potentially increases their status to match other partners in their firms, it also has the potential to minimize the impact of pro bono work on low-income clients by prioritized corporate interests (Adediran Reference Adediran2020a). Corporate clients do not often have the capacity to manage large pro bono programs in house and sometimes favor discrete or limited-scope legal representations (Rhode, Ricca, and Winn Reference Rhode, Lucy and Micheal2020). As a result, many law firms establish legal clinics to partner with corporate clients. These clinics are usually run either on weekends or for a few hours in the evenings.

A pro bono counsel explained that “a lot of times, what they really want is a one-day clinic. With [large corporate client], we have been doing one day quarterly immigration clinics for ten years now.” Even when firms and corporate legal departments co-counsel, corporate clients tend to handle discrete legal matters, as explained by a pro-bono counsel:

I think we do interact more with business development, potentially than we used to in terms of more companies asking to do corporate pro bono partnerships and more partners thinking that’s a good idea. We do a lot of pairing with in-house lawyers to handle cases, because usually the in-house lawyer will be responsible for some discrete aspect of that … but … it’s a very clinic heavy legal services market.

A pro bono counsel described the impact of such clinics as marginal for the poor and not worth expending pro bono resources for the benefit of business development relationships. He explained that any lawyer who tells you that these clinics help clients is just not being truthful: “You might touch one or two people but it’s marginal at best.”

Therefore, pro bono partners and counsels reframe their roles as business generators with corporate clients to boost their law firm status. However, this role can have downsides that impact the provision of legal services to low-income clients.

Conforming to the Culture of Billing

Pro bono partners and counsels also negotiate their status in law firms by strategically conforming to the culture of billing time to distinguish themselves from the administrative sectors of their firms. Billing time allows them to adhere to the logic of profit making to boost their status and autonomy. The culture of billing time is firmly rooted in the large law firm (Adediran Reference Adediran2020a). The act of billing time is what distinguishes the legal and administrative segments of large law firms. Individuals considered administrative or staff do not often bill their time and enjoy fewer privileges than those considered legal members of large law firms (Smigel Reference Smigel1964a). Partners, counsels, and associates are part of the legal department. Directors and staff are often administrative.

While pro bono partners are typically on the legal side of the firm, pro bono counsels—who make up the majority of lawyers who manage pro bono programs in Am Law 100 law firms—can be classified as either legal or administrative members of their firms depending on how their firms have structured the role. This division is not obvious externally since many pro bono counsels are considered staff members internally, even though their external titles may indicate “counsel.” What typically differentiates pro bono counsels who are on the legal versus administrative segments of their firms is whether they can practice law. As discussed in the next section, some firms strongly discourage or prohibit their pro bono counsels from engaging in law practice, which can negatively impact their status as lawyers in their firms.

Most pro bono partners and counsels explained that their firms do not track or monitor their hours, nor do they expect them to track their hours. Still, most pro bono partners and counsels track time spent on legal matters as opposed to administrative responsibilities.Footnote 2 Pro bono partners and counsels strategically record their time to “keep a record,” to “show that they’re working hard,” or to show that their firms are “getting [their] money’s worth.” A pro bono partner explained that she has a self-imposed “billable hour target in the same way that anyone else has a billable hour target[;] my spreadsheet looks a little bit different in that the bulk of my hours are pro bono hours, but I still have a 12-month number.” Another pro bono partner explained: “I mostly bill time just because every practice group leader at the firm bills time. I’m a practicing attorney. I’m not on the administrative side. I think some attorneys—some pro bono counsel who are not practicing—may not have those same billing requirements, but I’m on the billing side of the equation.” A pro bono counsel further explained that she records her time “to be able to promote myself and say, look this is what I’ve done. These are the number of hours I’ve spent. It’s a good thing to know … someone could look and say, wait what were you doing for seven hours on one thing and it’s pro bono management?”

Another pro bono counsel started keeping track of her time because of a need to show the amount of effort put into managing her firm’s pro bono program. She started “sending [hours] to the pro bono committee chair and committee members … because she thought, ‘nobody here knows what I do.’ And that’s kind of a dangerous position to be in.”

Another pro bono counsel keeps track of her time because it “helps the firm value what I do more when they can see how much I actually do. They gave me the option of not recording my time, but I feel like it really is important for them to see that I do a lot of things. … I wouldn’t want people to think that I’m slacking.” A pro bono partner had a similar comment with how firm management values her time since she does not generate revenue for the firm. While she believes that keeping track of her time is a waste of time, she does it because it allows her to show how a pro bono partner can add value:

I don’t bring in money into the firm, and so I think that there are a lot of high-level decision-makers within the firm that don’t understand how one can have value outside of money. And so, I decided that I would track my time the way that a billing lawyer tracks their time, so that I can show that I’m not goofing off, that my time is being spent working on firm initiatives, doing things that are appropriate for the firm. I personally think tracking my time is a little bit of a waste of time, but I don’t mind doing it. And I think that it gives a measurement that firm management understands.

Pro bono hours are useful for American Lawyer pro bono rankings, and firms are interested in raising or maintaining high rankings. A pro bono partner explained that “one of the reasons that we keep my time is that we report our total pro bono hours every year to various entities like the American Lawyer [] that publishes these rankings of firms from their pro bono scores annually. And so, I don’t want to lose any of the pro bono hours we have racked up. And since many of them are mine, it’s particularly important that I keep my records.” Lawyers who are internal staff pro bono counsels do not often track their legal or administrative time.Footnote 3 Among those pro bono counsels, not fitting into the billable hour culture can generate some regret. The following statement from a pro bono counsel is illustrative:

I do not have to keep track of my time, which is nice and also not nice. Like in a way, I like not keeping track of my time because timekeeping is so irritating and it’s time consuming. On the other hand, I wish the firm got credit for the work that I do. I sometimes do [] clinics when we have people who sign up for them and they can’t go, and I don’t want the organizations to be upset. Sometimes I will fill in to make sure that we don’t let our organizations down where they have clients there, but I try not to do that. And sometimes, our lawyers take on responsibilities and can’t meet them and I don’t want that to pass along to the legal service organizations with which we’re working.

In sum, pro bono partners and counsels strategically strive to conform to the culture of billing time to raise their status in their firms.

Establishing a Common Group Identity

Professionals often establish a common identity to increase feelings of group membership and navigate role ambiguity (Lounsbury Reference Lounsbury1998a; Lamont and Molnár Reference Lamont and Virág2002; Pilear Reference Pilear2018). Professionals can also establish a common identity to enhance collaboration (Kay Reference Kay2009; Comeau-Vallée and Langley Reference Comeau-Vallée and Ann2020). Within a profession, such as law, there can be segments or emerging specialties that distinguish themselves because of their client types, methodology, colleagueship, interests, and associations (Bucher and Strauss Reference Bucher and Anselm1961). Establishing a common identity can involve some or all of the following: developing formal organizational characteristics—such as procedures to elect officials and committees to investigate topics—and establishing a system—such as a listserv to facilitate ongoing dialog between members (Lounsbury Reference Lounsbury1998a).

Pro bono partners and counsels in law firms are at once lawyers, managers, administrators, recruiters, and supervisors. By the nature of their roles, they are often either the only lawyers who occupy their roles in their law firms or one of a handful of lawyers. These lawyers have established an external network of lawyers and other professionals who share similar identity to navigate their ambiguous roles in law firms. Pro bono partners and counsels have developed formal organizational characteristics through APBCO, which was established in 2006 (Nethery Reference Nethery2018). APBCO allows its members to develop a shared sense of purpose and common identity. As described by one of its founders, APBCO was first conceived by five pro bono counsels because of a “need to create something where we … help [] one another, where we are sort of band together as a community rather than having somebody on the outside who doesn’t know what we do, do that for us.” APBCO has since expanded. A Board of Directors was officially constituted in July 2009 (Dixon Reference Dixon2017). The organization now includes “over 200 attorneys and practice group managers who run pro bono practices in over 100 of the world’s largest law firms” (APBCO, n.d.).Footnote 4

APBCO members are connected via a listserv, where members can ask questions and receive feedback about how to navigate their roles in their law firms. A pro bono partner called the listserv “probably the most important feature of APBCO. … Essentially it is a space for all the people who do what we do to be in touch with each other.” APBCO members meet three times annually. Meetings serve as an avenue to socialize new members and collectively address legal and policy issues in local and national communities. Membership in the organization affords the “ability to think through issues [and] mobilize forces.” For example, “APBCO was the leader in getting [about] 150 firm leaders to send letters to Congress to not eliminate the Legal Service Corporation [LSC]” when talks were underway to defund the LSC during the Trump administration (Rauscher, n.d.). APBCO also recently launched the Anti-Racism Alliance to combat systemic racism. The alliance has now grown to 240 law firms with representatives in every US state (Bolado Reference Bolado2020).

In sum, pro bono partners and counsels navigate their ambiguous roles as lawyers, administrators, and managers in large law firms by striving to be perceived as “real lawyers” by representing pro bono clients, reframing their roles as business generators with corporate clients, conforming to the culture of billing time, and establishing a common identity through APBCO. APBCO serves as an avenue for pro bono partners and counsels to establish a collective identity and make sense of their ambiguous roles as lawyers and managers.

Negotiating Titles

In large law firms, titles are markers of prestige and intra-organizational status. Partners are revered and respected as senior members of their firms as they control workflow. Associates defer to the seniority and experience of partners they work for (Nelson Reference Nelson1988). Law firm counsels are neither partners nor associates (American Bar Association Standing Committee on Ethics and Professional Responsibility 1990). Research has shown that lawyers with counsel titles in law firms are significantly less satisfied with their careers than law firm partners (Markovic and Plickert Reference Markovic and Gabriele2018). A pro bono partner explained how being a partner has increased her status in her law firm:

[Becoming a partner] I think it helps me do my job. To associates, it [] telegraphs that this person is a partner and so, the firm attaches value to pro bono. And for the partners, I’m one of their colleagues. I wasn’t really afraid when I talked to them before but now, I think the way they view me is like, “you’re one of us.”

Another pro bono partner explained how the partner title provides access to prestige and important information:

If you’re a partner you have a certain level of respect within a firm. You have a certain level of access to information. When I was at [large law firm], there would be meetings and even though I was pretty senior, I wouldn’t be in meetings that partners would have about different things. You want to be at the table. So now I’m at every meeting I need to be at and have access to all the information I want. I often get a lot of people saying externally, whether they’re associates of the firm or recruits that it really means something that a partner at the firm runs the pro bono practice.

The partner title is so important that a former fee-generating partner who became a pro bono partner “was glad that [the firm] didn’t strip [her] of [her] partner title. I don’t know how much of a fight I would have put up about it if it had become an issue.” Another former fee-charging partner who returned to the firm to become a director described the importance of coming to a position that was somewhat equivalent to a partner and higher than a counsel:

The director title is not common at first. I made the title up and I didn’t realize that actually here there are other directors. … I knew I was going to come back as a partner, I didn’t want to come back as a counsel … counsel is kind of below partner, whereas director is to the side. I didn’t want to be below. I wanted to be to the side.

As explained by the above pro bono director, counsels do not have the same status as partners. A pro bono counsel described where counsels fit relative to associates in the law firm hierarchy:

I am a lawyer and I represent lawyers and to the associates a counsel is right below a partner. They are as close to a partner as you can get without being a partner. And the associates are under that [;] the associates [] have to treat me a certain way. Like I can direct them. I can make decisions. When I say we can’t do something, they don’t question it. That’s the counsel title.

For many pro bono counsels, the negotiation has not been for their law firms to promote them to partner.Footnote 5 Instead, some pro bono counsels have had to negotiate for their titles to be changed from “managers” or “coordinators” to counsel. When law firms first began to hire lawyers to manage pro bono programs, some retained the same titles given to coordinators who were not lawyers. Pro bono counsels who started as managers or coordinators have had to negotiate to be designated as counsels to increase their status. Twelve of the twenty-three pro bono counsels in the interview study expressly negotiated their titles either before accepting positions in their firms or during their tenure. For these pro bono counsels, the counsel title was crucial for being perceived as lawyers by other lawyers. A pro bono counsel who started her position as a pro bono coordinator recalled the difficulty of having a title that did not reflect her identity as a lawyer:

It just [didn’t] communicate that I’m an attorney. There are pro bono people who are not attorneys, and so it was very confusing. Before, [lawyers] may not have called me with a question because they didn’t realize I was an attorney, and now they will call me with a question because they see that I’m an attorney. … And then, externally, it helps because if you have a [coordinator] title they wouldn’t invite you to speak on a panel that was for attorneys.

Another pro bono counsel who also formerly had a coordinator title explained: “I did not want the word ‘coordinator’ in the title because I’m doing a lot more than coordinating. I’m making a lot of decisions and I’m setting policies with the advice and consent of the pro bono committee.”

In sum, titles in law firms are a marker of prestige. Pro bono partners and counsels negotiate their titles to reflect their status either as partners—or lawyers.

Negotiating Office Spaces

Office space is another important factor that determines intra-organizational status in law firms. Large law firms have traditionally designated office spaces and sizes hierarchically (Mockridge Reference Mockridge1966; Coe Reference Coe2017; McIntyre Reference McIntyre2019). The size, location, and other key features of an individual’s office—such as windows and views—often relates to the person’s status within a firm and, ultimately, to how the person is perceived by other lawyers in the firm. Partners tend to have very large corner offices with big windows and what are relatively the best views (Smigel Reference Smigel1964b). Some firms have counsel offices, which are smaller than partner offices but are generally larger than associate offices. Associate offices are usually smaller than partner and counsel offices but often have windows. Paralegals in law firms tend to sit in interior windowless offices.

Several pro bono partners and counsels spoke about the connection between the value of their positions and the size of their offices and whether their offices have windows. They also described how office space signals the value and worth of pro bono partners and counsels both within law firms and externally. Indeed, pro bono partners and counsels believe that their offices signal their firms’ commitment to pro bono work as a form of public service. Yet the offices that pro bono counsels occupy do not always reflect their lawyer credentials. A pro bono counsel explained that “people are going to look and be like ‘pro bono is obviously really important because this person has this [office] and then the status of pro bono and those things are linked. So, I think part of it is trying to measure your value, your worth and an internal office is a statement by the firm.” The same pro bono counsel was inadvertently assigned a partner-size office, giving other lawyers the impression that she was a partner, which boosted her status internally:

I don’t think [the firm] would have given [the partner-size office] to me if they realized that it was a partner type of office. But it’s so helpful because when I have people come to my office, I get some respect. People assume I’m a partner all over the place within the firm, outside the firm. You know what, I don’t correct them.

Whether an office has a window can also be a signal of status. A pro bono counsel detailed the importance of obtaining an office with a window like other lawyers in her law firm. In her case, a summer associate was so outraged that she was “doing so much good work for the firm” and had an office that was intended for a paralegal. The summer associate felt compelled to address the issue, telling the pro bono counsel that “what they’re doing is wrong. And they’re doing it because you help poor people and you don’t bring in money for the firm. You need to have an office that’s appropriate for you because you’re a lawyer.” The pro bono counsel said that she was ashamed and sought ways to advocate for a lawyer’s office space by tapping into APBCO’s data about the kinds of offices other pro bono counsels have in other firms. She gave her law firm’s management the data. She continued: “[O]ne of the happiest moments of my career was when I eventually got a window.” Another pro bono counsel was advised to request an office with a window prior to accepting the position: “I think that was probably a conversation before I accepted the job. She said you should ask for a window. And when they got back to me, they said, “real estate’s very, very tight. But we got you an office with the window.”

To be sure, not every lawyer in this role is relegated to windowless and internal offices. However, the data suggests that female pro bono counsels are more likely to occupy windowless offices than their male counterparts. Regardless of gender, all thirteen pro bono partners sit in large, partner-size offices with windows. Two male pro bono counsels however successfully negotiated for large partner offices for the sole purpose of being perceived as partners in their law firms as detailed below:

So, when [firm chair] and I negotiated, he said, there’s two preconditions. I said; what are they? He said, one you’ll never be a partner. And I said, ‘oh, why should I [care] about that. I said, ‘I just want to look like a partner, I want to be in a position where the young lawyers don’t think I’m window dressing. I want the youngsters to think that I’m important to the firm. So, we negotiated [and] I got a big partner office.

I asked the above pro bono counsel why it was important to be observed internally as a partner, and his response was that he did not want to be perceived as symbolic: “I didn’t want people to think, ‘oh, he was an add-on, he’s not an integral part of the firm, look at the office size, look at the assistance he’s given. Instead, given the values at that point, it was; oh, he’s got a partner-size office.” He went on to explain that when he first arrived at the firm, many lawyers introduced him as a partner, and, initially, he corrected them but quickly stopped doing so and allowed people to perceive him as a partner.

Similarly, another male pro bono counsel successfully negotiated for a partner office by urging management that he “had to be in a position to persuade associates that the firm takes pro bono seriously, so I really should have a fancier office because people pay attention to this stuff.”

Nevertheless, even for pro bono partners, office space can model status rankings to differentiate them from fee-charging partners. A pro bono partner described how her law firm with similar sized offices still finds a way to differentiate between important individuals and those that are not high status: “[T]he difference is what your view is. So, the super, super senior, super important people have eastside office views and corner offices. I sit on the [number] floor.”

Therefore, office spaces are a marker of status and prestige in law firms. Pro bono partners and counsels negotiate their office spaces to raise their status. From my observation, only female pro bono counsels occupy windowless offices, which can be a marker of lower status in law firms.

GENDER DIFFERENCES AND INEQUALITY AMONG PRO BONO PARTNERS AND COUNSELS

In addition to negotiating office spaces, there are three important findings with respect to gender differences and inequality among pro bono partners and counsels. The first finding is that, despite the fact that women comprise about 77 percent of all pro bono partners and counsels, there is a slightly higher—although not statistically significant—occurrence of men who are pro bono partners in comparison to women. As shown in the results of the chi square analysis in Table 2, we would expect to observe 5.7 male partners but observe nine, and we would expect to observe 21.3 female partners but observe only eighteen.

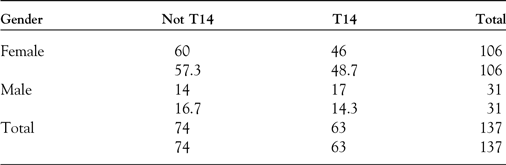

The second finding is that there is a statistically significant difference between the substantive areas of law that men and women practice in their current positions even though men and women are similar in other ways. Men and women have similar backgrounds and experiences in terms of tiers of law schools attended, prior legal practice settings, and prior substantive areas of law practiced. Indeed, I found no statistically significant relationship between gender and any factor except current area of practice. Specifically, Table 6 shows that, while we would expect 48.7 women to have attended T-14 law schools, we observe forty-six. We would expect 14.3 men to have attended T-14 law schools, and we observe seventeen, which is slightly higher, but the differences are not statistically significant.

TABLE 6. Law school tier by gender

Notes:

In each cell, the upper value is the observed frequency and the lower number is the expected frequency. Pearson chi 2(6) = 1.2643; p = 0.261.

Similarly, in terms of prior legal practice settings as indicated in Table 4, we would expect 32.3 women to have been elevated to these positions from associates in law firms, but we observe thirty-seven. For men, we would expect 9.7 but observe five. However, the differences are not statistically significant. The results are the same for the substantive area of law practiced prior to obtaining their current positions in Table 5.

However, there appears to be a gender divergence once the lawyers assume their current positions as indicated in the chi square analysis in Table 3. Men are more likely to focus their pro bono practices on criminal representation, engage in multiple areas of practice, or impact litigation. Women, on the other hand, are more likely to focus on family law, immigration, and human rights law.

Law firms ascribe differing levels of prestige to different areas of law. For instance, law firms value impact litigation for its often high-profile and prestigious experience (Garth Reference Garth2004; Adediran Reference Adediran2020b). Some law firm lawyers may therefore prioritize impact litigation. Similarly, criminal representation, which includes death penalty cases, can yield similar high-profile results. A multi-practice portfolio may also be considered prestigious in some firms. It is probable that the men in these positions are purposeful about the substantive areas of law they assume to raise their profiles in law firms that are traditionally hierarchical, which further increases their relative status and autonomy in other spheres of the firm. Relatedly, women are also statistically significantly less likely to practice law and exclusively manage pro bono matters. As discussed below, not practicing law negatively impacts the autonomy to approve pro bono matters. Not practicing law also probably makes it more challenging to be perceived as a real lawyer in comparison to the lawyers who practice.

The third finding is that there is a gender difference in relative professional autonomy experienced by men and women. Professional autonomy is an important ideal for lawyers and extends well beyond the interests of clients (Nelson Reference Nelson1985). The approval of pro bono matters is an important role of the pro bono partner or counsel in a law firm. All legal matters must be approved to ensure that there is no conflict between new clients and law firms’ existing clients. The approval process is such that public interest legal organizations send pro bono matters to pro bono partners and counsels who then disseminate matters to associates and partners in their firms. The approval process must occur before matters are assigned to individual pro bono lawyers or while they are being assigned, but no pro bono matter can proceed without approval. Pro bono partners and counsels have varying degrees of autonomy and decision-making power, ranging from the ability to make unsupervised decisions with little input from others, to the need to receive approval from multiple levels of the firm.

I find two levels of autonomy for pro bono partners and counsels. The first level is ascribed to partners and pro bono counsels who are designated as counsel both internally within their law firms and externally on law firm websites and other platforms. The second level of autonomy is for pro bono counsels who are considered counsel externally but not internally within their firms. Internally, these pro bono counsels are staff or administrative members of their firms. Law firm policy often prohibits, or makes it difficult for, external counsels and internal staff to practice law; they are often only managers of pro bono programs. Pro bono counsels who are lawyers both internally and externally enjoy greater autonomy in decision making, over and above pro bono counsels who are designated as counsels only externally.

Of the 124 lawyers with data on their current substantive areas of law, fifty-one do not practice law. Of those, forty-eight are women (94 percent), and only three are men. The difference is statistically significant. The three men also appear to have practiced law in the past but are currently in retired or senior status in their positions. This is not true for the women. These mostly female lawyers—who do not or cannot practice law—comprise about 37 percent of all pro bono partners and counsels in large law firms.

Pro Bono Partners and Pro Bono Counsels: Internal and External

Pro bono partners and lawyers designated as counsel both within their law firms and externally on their firms’ external platforms are typically able to approve pro bono matters with limited oversight from firm management. These pro bono partners and counsels tend to approve matters either before or after management level approval. When they approve before management, the final approval is often a rubber stamp of their decisions. A male pro bono partner who has discretion to approve matters that are often rubber stamped by management described his process:

I have a fair amount of discretion. I approve and then it goes to somebody who is working in the management level for a final approval. It’s extremely rare that something bounces from that level … the level after me is not a rigorous level, and so if something is going to get caught or questioned, it’s going to happen here. … I take that as a vote of confidence in my judgment, so I take that very seriously.