INTRODUCTION

Why do activists employ international human rights law in domestic policy disputes and to what effect? Can international human rights law play an important role in cases where its direct application and justiciability by domestic courts is questionable? Even advocates of international law point to the lack of enforcement mechanisms in much of human rights, particularly in the area of socioeconomic rights. Indeed, socioeconomic rights have lagged behind their civil and political counterparts in terms of recognition and enforcement. Even where these rights are justiciable—meaning that they can be contested in court—they tend to be so in only limited ways, and there are few enforcement mechanisms outside the state. As a result, scholars contest the extent to which much of human rights law actually matters in domestic policy disputes (Langford Reference Langford2008). Additionally, some scholars worry about the ways in which rights talk more generally can limit the scope of movement demands and legitimate state power at the expense of movements (Marx Reference Marx and Robert1978; Brown Reference Brown, Sarat and Thomas1998; Tushnet Reference Tushnet1984).

The German movement against tuition fees offers an interesting case study to explore these questions. After a 2005 German Federal Constitutional Court case authorized federal states (Bundesländer) to collect tuition at institutions of higher education, several western German states implemented tuition fees. They saw it as an opportunity to address endemic underfunding of higher education and to trigger competition between universities for students and their tuition dollars. Unlike the introduction of tuition in Great Britain seven years earlier, which was met with little organized opposition, German states faced massive opposition. In 2007, the Free Association of Student Bodies (freier zusammenschluss von studentinnenschaften [FZS]) and Germany’s largest education union, the Education and Science Workers’ Union (Gewerkschaft Erziehung und Wissenschaft [GEW]), went so far as to lodge a complaint with the United Nations (UN) Commissioner for Human Rights in Geneva. The re-introduction of tuition fees in Germany, they argued, violated Germany’s commitments to the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).Footnote 1

The lodging of a human rights complaint with the UN signaled a shift in the debate over tuition fees in Germany. In the previous decade, political elites had largely framed higher education in terms of its macroeconomic, rather than social and political, benefits. But, by 2010, as the movement against tuition fees reached its apex with a nationwide education strike that included primary, secondary, and university students, along with labor unions and various political organizations, their tune had decidedly changed. The conservative Christian Democratic Union’s (CDU) 2009 general election manifesto described education as “the key to a self-determined, solidary, and responsible life” and an educated populace “the source of cultural development, of social cohesion, as well as the economic success of our country.”Footnote 2 The same year, the Social Democratic Party (SPD) went even further, describing education to be a “human right” because it leads to “actual equality of opportunity.” The shift in language at the highest levels of Germany’s two largest political parties was a direct response to the political pressure that student activists, organizations, and labor unions generated. By 2014, after over a decade of organizing and mobilizing, not a single state charged universal tuition fees.Footnote 3

The case of tuition fees and the student-led social movement is noteworthy for several reasons. First, it defied trends toward privatization elsewhere, indicating an under-examined role for civic actors in the face of broad welfare state retrenchment. Higher education is increasingly expected of the workforce in advanced capitalist societies. At the same time, many states have moved to privatize or expand the privatization of previously publicly funded institutions, including higher education. Second, there is much scholarly debate about the efficacy of using international human rights law in domestic policy disputes. The ICESCR invoked by German activists, for example, had only an oversight committee that could issue non-binding recommendations to state parties until 2013, when an optional protocol providing some individual complaint mechanisms went into force for its twenty-four state members (Germany has neither signed nor ratified the optional protocol).Footnote 4 Contrary to some scholars’ concerns about the ways in which rights talk can harm movement goals, human rights claims were critical to the success of the German movement against tuition fees. Activists invoked human rights to resist political elites’ framing of education as a private good and students as consumers and to broaden the issue to include social inclusion and justice throughout the German education system. The mobilization of human rights law also was an effective means by which activists generated media attention and pressured politicians.

THEORY

Higher Education, Rights Frames, and Legal Mobilization

In recent years, many advanced capitalist states have adopted policies of retrenchment from what Gosta Esping-Andersen (Reference Esping-Andersen1990, 2) refers to as the “Keynesian welfare state” or “welfare capitalism.” According to this understanding, the welfare state consists not only of the individual social and redistributive policies present in varying forms across states but also the more general political economy of advanced capitalist states and human outcomes in terms of employment, wages, (in)equality, and security in an increasingly globalized financial system. Retrenchment has come primarily in the form of privatization and deregulation (and not necessarily in reductions in public expenditures)—states have increasingly relied on market mechanisms to provide the same benefits, with highly unequal results.

Modern education functions much like other components of the social welfare state. Education is fundamentally distributory in that access to education impacts future earnings, social mobility, marketplace flexibility, and a society’s economic competitiveness (Oreopoulos and Petronijevic Reference Oreopoulos and Uros2013; Picketty Reference Piketty2014; Herschbein, Kearney, and Summers Reference Hershbein, Kearney and Summers2015). For many, education is also liberatory, a way to break free from the boundaries of social constraints, economic dependence, and discrimination (Anderson Reference Anderson1988; hooks 1994; Freire Reference Freire2000). Indeed, the tensions between the economic, social, and political roles of education have characterized policy debates over state responsibilities in its provision. The same social welfare dynamics that characterized primary and secondary education in the first half of the twentieth century now also apply to postsecondary or tertiary education (higher education, vocational training, continuing education, and adult education). Postsecondary education is approaching universality as political elites and businesses see it as essential to competition in a changing, increasingly globalized market (Taylor Reference Taylor and Eggins2003).

At the same time, states have reduced resources to support and finance public institutions, including schools. This has come in the form of movements for private vouchers and charter schools at the primary and secondary levels; as efforts to make schools up to and including postsecondary operate according to competitive market principles, competing with each other over students and scarce resources; and as a move toward private financing of higher education (Levin Reference Levin2001; Johnstone & Schroff-Mehta Reference Johnstone, Schroff-Mehta and Eggins2003; Angus Reference Angus2015; Pattillo Reference Pattillo2015). Shifts in financing are symptomatic of broader structural changes in higher education, what some scholars have variously referred to as academic capitalism (Slaughter and Rhoades Reference Slaughter and Gary2009; Hoffman Reference Hoffman2012), corporatization of the university (Johnson, Kavanagh, and Mattson Reference Johnson, Patrick and Kevin2004; Chan and Fisher Reference Chan and Fisher2008), and the neoliberal university (Canaan and Shumar Reference Canaan and Shumar2008; Rustin Reference Rustin2016).

Although scholars disagree on how best to understand the changes in higher education, as well as on preferable alternatives, they identify a number of similar trends that are impacting universities across advanced capitalist societies. More researchers are competing over increasingly scarce resources to conduct research, resulting in research increasingly directed toward providing commodifiable products that can supplement their research funding and university operations. Teaching positions are increasingly filled by contingent faculty members, often working under short-term adjunct contracts that, in many cases, pay below minimum wage. Administrative staff positions have ballooned, directing scarce resources away from the core academic functions of the institutions.

Mobilizing Law against Retrenchment

As with other social institutions, changes to education are likely to generate a lot of skepticism and opposition among members of society. As a result, scholars of welfare retrenchment have argued that it is important to distinguish processes of retrenchment from processes of expansion. As Paul Pierson (Reference Pierson1996, 143–44; emphasis in original) argues, “expansion involved the enactment of popular policies in a relatively undeveloped interest-group environment,” while “retrenchment generally requires elected officials to pursue unpopular policies that must withstand the scrutiny of both voters and well-entrenched networks of interest groups.” That is, policies create politics, what scholars refer to as policy feedback effects (Thelen Reference Thelen1999): the very existence of an institution like higher education fundamentally changes the political landscape that created it. Scholarship on policy feedback effects emphasizes several different types of feedback generated by policies, including the expansion of state capacity and bureaucracies, the emergence of entrenched interest groups that serve the constituencies constituted by a policy; lock-in effects that foreclose previously open policy options and favor path dependency; the relationship between the private and public provision of goods; and the effects of policies on political participation (see Béland Reference Béland2010). In all but the last and rarer approach, policy feedback effects are mostly understood from the top down and are concerned either with the ways in which elites determine how best to pursue retrenchment by hiding unpopular policies (usually through gradual reform) or the role of top-down mobilization by interest groups. Pierson (Reference Pierson1996, 147) suggests that “the emergence of powerful groups surrounding social programs may make the welfare state less dependent on the political parties, social movements, and labor organizations that expanded social programs in the first place.”

This study departs from much of the literature on retrenchment by adopting an explicitly bottom-up approach. In particular, I borrow and build on the work of socio-legal scholars, taking up the call of Sandra Levitsky, Rachel Kahn Best, and Jessica Garrick (2018, 710–11), who argue that “applying a constitutive perspective to understanding how laws structure political claims and conflicts would enrich our understanding of the state’s role in creating and maintaining economic inequality.” After all, as Frank Munger (Reference Munger and Sarat2008 345) intones, “welfare in all its forms has served the dominant economic interests, especially their interest in stabilizing the steady supply of labor.” That is, inequality is part and parcel of such policies and, in turn, impacts the opportunity structures available to people in resisting or demanding change to those policies. The constitutive approach provides scholars with the opportunity to understand the many aspects of feedback effects by “assessing the impact of legal ideologies and court decisions at one point in time in shaping the capacities, interests, and beliefs of political actors and the mass public at future points in time” (Levitsky, Best, and Garrick Reference Levitsky, Rachel Kahn and Jessica2018, 725–26).

Put another way, while institutional forms and developments condition the nature of distributional struggles, they do not independently determine the outcomes. Instead, people on the ground interact with and within these institutions. This structural context, what scholars often refer to as “political opportunity structures,” plays a constitutive role in the formation of how individuals understand their preferences, creates a gradient of appropriate strategic action, and provides the environment and institutional opportunities within which political conflicts are structured and take place (McCann Reference McCann1994; Cichowski Reference Cichowski2007; March and Olsen Reference March, Olsen, Moran, Rein and Robert2011; Vanhala Reference Vanhala2018). One framework within which to understand these conflicts is known as legal mobilization theory, which examines key factors of social and legal struggle “when a desire or want is translated into a demand as an assertion of one’s own rights” (Zemans Reference Zemans1983, 700). Whether and when individuals and groups mobilize law is a question of how they perceive and understand a given problem and whether they understand that problem as a matter of public interest that ought to be determined in law. Legal mobilization can include formal strategies like litigation but broadly encompasses the invocation of law on behalf of political demands. For example, a student has mobilized law whether they have filed a formal court complaint against tuition fees or simply argued to their friends that tuition fees violate their legal rights.

Critics of legal strategies offer a number of concerns. First, even when a movement secures a favorable court decision, it can be challenging to identify the direct causal impacts (Rosenberg 1991), and such decisions may actually instigate counterproductive backlashes that harm movement goals in the long term (Klarman Reference Klarman1994). These critics are skeptical about the efficacy of legal strategies even when they are employed only discursively. Mark Tushnet (Reference Tushnet1984) argues in the United States that rights are, at best, impotent and, at worst, clearly harmful: they benefit those with power more often than those without, and, because of the way that courts play a role in affirming rights, they rarely find positive rights to be legitimate. That is, by engaging in rights talk, when the claims for positive rights are rejected in court, long-term social justice campaigns can be harmed by limiting the scope of the potential claims that activists can make. Still others worry about the ways in which rights can over-individualize and depoliticize claims, making collective action and more transformative change less likely (Marx Reference Marx and Robert1978; Brown Reference Brown, Sarat and Thomas1998).

Precisely because law is frequently a source of inequality, and may often be employed to reject demands for justice from below, there are ample opportunities to study these complex relationships, including how law might nonetheless provide symbolic and strategic benefits. Legal mobilization scholarship, in particular, has brought additional attention to the role of rights, highlighting both how they can act as “important symbols of legitimacy” for liberal legal orders (Scheingold Reference Scheingold2004, 57) as well as how they can help “politicize needs by changing the way people think about their discontents” (131). That is, rights may well help to legitimize extant distributions of social power, as critics contend, but they also can play a role in developing a legal consciousness that is mobilizing in favor of social change (McCann Reference McCann1994; Lovell Reference Lovell2012; Marshall Reference Marshall2016).

Higher Education as Citizen’s Right, Fundamental Right, Human Right, or Privilege?

The status of higher education as a human right is, perhaps unsurprisingly, a highly contested notion. While some are very skeptical that international law in general does much more than advance the interests of powerful states (Mearsheimer Reference Mearsheimer1995), even advocates must contend with relatively sparse international enforcement mechanisms. Monitoring committees tasked with overseeing human rights treaty commitments largely rely on states and non-governmental organizations to report on implementation. Most of the time, these committees are empowered only to make non-binding recommendations. Outside regional human rights systems, there are no uniform judicial bodies tasked with arbitrating human rights treaty implementation. Instead, the legal significance of human rights is largely dependent on how those human rights are integrated into a country’s domestic legal system. Like many other economic, social, and cultural rights, the necessity of positive state action in providing their material guarantees has generated claims by many theorists, scholars, and political elites that they can hardly be understood to be human rights (for an overview, see Kotzmann Reference Kotzmann2018; see also Mayerfeld Reference Mayerfeld2016, who contends that socioeconomic rights are necessary and complementary to their civil and political counterparts). Moreover, whereas primary education is largely universal in many parts of the world, higher education remains more exclusive and is often treated as a privilege.

Whether higher education is a human right matters, not least because it suggests a more inclusive definition of who ought to benefit. If higher education is merely a right of citizenship, for example, then anyone who is not a citizen has no claim to a financially accessible higher education. If it is merely a privilege, then the state’s responsibility to students is even more diminished. Given skepticism both about the efficacy of international human rights law, in general, and the applicability of socioeconomic rights, in particular, we return to the questions that opened this article: why do activists employ international human rights law in domestic policy disputes and to what effect? Can international human rights law play an important role in cases where its direct application and justiciability by domestic courts is questionable? While legal mobilization scholarship is broadly interested in the invocation of law and rights on behalf of political demands, frameworks emphasizing discursive opportunity structures and the vernacularization of human rights law into local contexts provide additional analytical leverage to understand which rights are mobilized, why, and with what impact.

Discursive opportunity structures are culturally resonant vocabularies and assumptions, which Myra Ferree (Reference Ferree2003, 309) suggests “can be found in major court decisions, as well as in the prior constitutional principles they invoke and in subsequent legislation written to be consistent with these principles.” By examining the cultural and legal context in which a struggle is taking place, we can make sense of whether certain discursive frameworks are likely to be “resonant,” complementing local norms and ideologies, or “radical,” challenging them. By employing this sort of analysis, we can begin to understand why certain frames are adopted as well as how they fit into a broader cultural context. This article adopts the insights of vernacularization scholars, thinking specifically about how international human rights are “localized” to make sense in a domestic context, and how this translation process contributes to changes both in the demands made by a movement and in that movement’s understanding of human rights (Merry Reference Merry2006; Chua Reference Chua2015; Kahraman Reference Kahraman2018; Handmaker and Matthews Reference Handmaker and Thandiwe2019). When activists invoke discursive frames, they change the context of their struggle and perhaps even how they envision what they are doing.

Human rights mobilization in Germany was not based on a naive belief that such claims would win the day in court or that the general public would come to agree with the view that higher education is a human right (though either outcome would surely have been welcomed by the activists). In fact, one of the major barriers to winning the argument among the general public was (and remains) the way in which higher education access in Germany has continued to reflect extant inequalities both formally and informally. Supporters of tuition fees insisted that they were therefore fundamentally just because tuition shifts the burden of financing the private benefits of higher education to those privileged enough to enjoy those benefits. Nonetheless, human rights offered an important and culturally resonant symbolic guarantee to Germany’s social democratic traditions in the politics of higher education; it was, in other words, a readily available discursive resource. As I argue, the mobilization of human rights served to expand the demands and strengthen the coalition supporting the movement against tuition fees, while also generating broader public pressure on policy makers.

RESEARCH DESIGN

Case Selection

The battle over tuition fees in Germany provides a compelling case to study the mobilization of human rights law in domestic contexts. German higher education has long been an exclusive institution, reserved for students who earned their Abitur at university preparatory schools. Efforts to expand access have been somewhat successful: 70.25 percent of college-aged students enrolled in a tertiary institution (which includes vocational schooling) by 2017, compared to only 33.66 percent in 1991 (World Bank 2020). Despite these efforts, according to a 2018 study, while 79 percent of Germans between the typical university ages of eighteen and twenty-four came from families where neither parent had earned a degree from an institute of higher education, only 45 percent of students beginning university that year came from such families. This inequality is even starker for students from immigrant families (Kracke, Buck, and Middendorff Reference Kracke, Daniel and Elke2018). These dual challenges of increasing enrollment and persistent inequality are further complicated by the endemic underfunding of higher education in Germany, which has consistently spent below the average for countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. In a context where access is restricted but costs are “universally” free, it is not obvious that an argument about the human right against tuition fees is likely to register. Indeed, many signatories to the ICESCR have higher tuition fees than was the case in Germany.

Germany is the most highly populated member state of the European Union (EU), with over 80 million residents. Policy competences are divided between the federal government and sixteen federal states. Federal states have primary jurisdiction over education, according to Article 7 of the Basic Law, Germany’s Constitution, except in the area of higher education admissions and graduation requirements, research funding, or in areas where the states mutually consent to federal action. In no small part in reaction to its own history, Article 25 grants some direct applicability of international law, providing that “[t]he general rules of international law shall be an integral part of federal law. They shall take precedence over the laws and directly create rights and duties for the inhabitants of the federal territory.”Footnote 5 Germany has a multi-party system but has traditionally been dominated by the CDU, on the center right, and the SPD, on the center left, and these parties have a storied history of joining together in government as a “Grand Coalition.”

Data and Methods

This study draws on a variety of data sources and methodologies. I rely extensively on content analysis of public documents from various organizations involved with the movement, contemporary accounts in books or edited volumes by movement activists, as well as political party manifestos, coalition contracts, media reports, and court decisions. I was also able to collect local materials from student groups and former activists. I used the Nvivo qualitative research software to identify and code major recurring themes and to identify the ways in which different actors thought about them. The coding scheme was developed based on the relevant socio-legal literature and studies of shifts in the politics of higher education. For both elite and activist materials, I coded for claims about the role of higher education specifically and education generally; different types of discursive approaches to those claims (for example, social democratic, human rights, privatization, competition); different types and levels of legal claims (domestic, international) and the content of those legal claims (for example, anti-discrimination, inequality); as well as connections made between higher education and other policy areas (for example, economic inequality, labor, primary and secondary education, global competition). The content analysis was essential to developing a timeline of movement formation and activities as well as for identifying key arguments offered both by elites and activists.

I supplemented this content analysis with ethnographic methods in order to gather additional insights about internal organization; coalition formation; how activists think about, talk about, and develop strategy; and how their views of, and beliefs about, state responsibility and education informed their activism (McCann Reference McCann1994; Adam Reference Adam2017). As tuition fees continue to exist in some forms (either as fees for students who take too long to graduate or for international students), the key organizations that were involved in the German movement are still active and continue to organize around tuition fees. I acted as a participant observant at events, meetings, and strikes, and I conducted semi-structured interviews, including of former directors of the national-level campaign against tuition fees and representatives of the GEW education union. Interview participants were identified, first, through public organizational documents and newspaper accounts and, subsequently, through snowball sampling. I first made contact with the major involved organizations during a two-week research trip to Berlin in 2016 and conducted field research in Berlin from September 2018 to July 2019. In total, I interviewed fifteen people, with all but one interview conducted in German. Although many of the individuals I interviewed would independently raise the idea of education as a human right, I also included questions that prompted them to discuss the political significance of this framing. Specifically, I asked: “Already in the [Action Coalition’s founding document], we see references to the human right to education as well as the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Why?” Based on the response, I then had follow-up questions about whether human rights-related actions were helpful, important, or harmful and in what ways.

HUMAN RIGHTS IN THE GERMAN MOVEMENT AGAINST TUITION FEES

Adopting and Adapting: Invoking International Human Rights Law in Higher Education Debates

From 1970 until a 2005 Constitutional Court case authorized federal states to levy tuition fees, the federal states of West Germany (and, later, the states of the reunified Federal Republic of Germany) adhered to a state pact developed in the aftermath of the student movements of the late 1960s that, among other things, eliminated the tuition fees that had existed in various forms before 1970 (Krause Reference Krause2008, 22–25). The turn toward tuition-free higher education at the beginning of the 1970s occurred as socioeconomic rights made gains under the 1966 ICESCR, which Germany ratified in 1973. When German states agreed to eliminate tuition fees in 1970, intentionally or not, they fulfilled part of Article 13 of the ICESCR before ratification, which reads:

Article 13.

1. The States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right of everyone to education. They agree that education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and the sense of its dignity, and shall strengthen the respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms. They further agree that education shall enable all persons to participate effectively in a free society, promote understanding, tolerance and friendship among all nations and all racial, ethnic or religious groups, and further the activities of the United Nations for the maintenance of peace.

2. The States Parties to the present Covenant recognize that, with a view to achieving the full realization of this right:

…

(c) higher education shall be made equally accessible to all, on the basis of capacity, by every appropriate means, and in particular by the progressive introduction of free education. (Emphasis added)

But while the pact between states endured into the 1990s, attempts to write the prohibition into the federal Higher Education Framework Act (Hochschulrahmengesetz) consistently failed.Footnote 6 By 1998, despite a friendly SPD-led government in coalition with the Green Party that had won in part by promising to ban tuition fees at the federal level, and several years before the Constitutional Court would undo that promise, students, education unions, and other organizations were already organizing against such fees. They were driven to action in part by the increasingly market-based discussions of education, the introduction of fees in Great Britain in 1998, and the beginning of the “Bologna Process”—reforms that sought to standardize degree programs, facilitate labor mobility, and make European higher education more competitive with its US counterparts (Huisman and van der Wende Reference Huisman and Marijk2004). In the 1999 Krefelder Aufruf, the declaration that marked the establishment of the Action Coalition against Tuition Fees—initially a campaign that would become a subsidiary organizing front of the Free Association of Student Bodies—opponents of tuition fees laid out their arguments: tuition fees would lead to the privatization of social risk, transforming education from a public good to a consumer service; tuition fees would undermine solidarity between members of society; tuition fees did not fit the German conception of the social contract and would reproduce structural inequalities by coupling education opportunities with private income; and tuition fees would transform students from democratic members of the university into customers.Footnote 7 The Krefelder Aufruf demanded a federal legal guarantee of tuition-free higher education, a rejection of “elite” and private higher education, equal and tuition-free access to academic and career-oriented tertiary education programs, and, almost as an addendum, “[t]he adoption and observation of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, ratified in 1973, with which the federal government committed itself to the progressive introduction of tuition-free higher education (likewise affirmed in Article 26 of the UN Declaration of Human Rights in December 1948).”Footnote 8

In response to several states with CDU-led governments in the late 1990s and early 2000s that introduced tuition fees targeted toward students seeking a second or secondary degree, or who had taken too long to graduate, the federal government amended the Higher Education Framework Act in 2002. Section 3, Article 1, of the act declared that first-degree students, and subsequent degrees that build upon the first for the purposes of career qualification, must be tuition free (though states could go further in providing tuition-free education). A second change concerned employment relationships in institutes of higher education. In response, the governments of Baden-Württemberg, Bavaria, Hamburg, Saarland, Saxony, and Saxony-Anhalt lodged a complaint before the Federal Constitutional Court in 2003, claiming that the changes to the law were a violation of Articles 70 and 75 of the Basic Law, regarding states’ rights under federalism and the regulations of state employees by the federal government. The Federal Constitutional Court decided the case on January 26, 2005, ruling in favor of the states that the law was an unconstitutional violation of the Basic Law’s federalist principles.Footnote 9

For activists who had already begun organizing in the 1990s against tuition fees, the decision was a major loss, but it did provide one clear legal opportunity. The court acknowledged that tuition fees could lead to a “social selection of students,” whereby only those who can afford tuition fees will be able to attend higher education. Such fees, the court determined, would not fit into the “social contract” model fundamental to the German Basic Law. But the court was skeptical that all tuition fees would do that, as Germany’s tuition-free higher education system already featured more social selection than systems in other countries that charged students. Olaf Bartz, who as a student was the Action Coalition’s first national director from 1999 to 2001, explained in an interview that, while the decision was adverse in that it permitted fees, it found that fees “may not have any prohibitive effect on academic studies, nor may the conditions of entrance to academic students lead to social segregation,” which he connected to Germany’s obligations under the ICESCR. As a result, he remarked: “Neither side particularly liked this decision.”Footnote 10 That is, while the court’s decision authorized tuition fees, it made clear that there were limits to how high tuition could grow, which would be determined on the basis of whether the fees were consistent with the German understanding of the social contract. Moreover, the court, in identifying the relevant domestic rights that are called into question, makes explicit reference in its decision to the commitments that Germany made in the ICESCR with regard to accessibility in higher education.

The CDU won a plurality in the Bundestag elections that September, and the Grand Coalition that it formed no longer officially opposed tuition fees. At the beginning of the next academic year, Bavaria introduced tuition fees. Several states followed Bavaria over the following two years: Lower Saxony and North Rhine Westphalia introduced tuition fees in October 2006; Baden-Württemberg and Hesse in March 2007; and Hamburg and Saarland in October 2007. The laws regulating tuition fees varied across states, but, in most cases, they set the cost of tuition at five hundred euros per semester or one thousand euros per year.

While the Krefelder Aufruf’s reference to the ICESCR presaged its increasing invocation over the next fifteen years, and even the Constitutional Court case authorizing tuition fees took seriously commitments under the ICESCR, efforts to litigate human rights claims nonetheless quickly ran into domestic barriers. Activists challenged a law the North-Rhine Westphalian state parliament passed in March 2006 establishing tuition fees before the Higher Administrative Court for North-Rhine Westphalia, arguing that it violated the Basic Law’s Article 12(1) guarantee to freedom of profession and Germany’s ICESCR Article 13(2c) commitments to the “progressive introduction of free education.”Footnote 11 On appeal in 2009, the Federal Administrative Court (Bundesverwaltungsgericht) rejected the students’ argument. While the Federal Administrative Court, like the Federal Constitutional Court before it, took seriously the promises of the ICESCR, it nonetheless concluded that there is a legitimate difference between the treaty’s aspirational text and the right of states to find the best way to achieve those goals. The ICESCR was unlikely to provide an effective avenue for challenging tuition fees in court.Footnote 12

Discursive Opportunity Structures and the Human Right to Education in Germany

Human rights law presented a readily available resource with cultural, political, and legal salience in German society. Indeed, the very nature of human rights guarantees to education are bound up with its history. Memories of the strong and well-developed German education system during the national socialist period were salient to international human rights treaty drafters—in particular, the ways in which education was “corrupted by an ideology which dictated blind obedience and racial hatred” (Beiter Reference Beiter2006, 463–64). Thus, they included Article 13(1) guarantees of the ICESCR to education “directed to the full development of the human personality and the sense of dignity” and with the mandate to “strengthen the respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms” and promote tolerance “among all nations and all racial, ethnic or religious groups.”

Moreover, the human rights conception of education had analogues in social democratic discourse extending back to the nineteenth century. In the Gotha Program of 1875, the SPD positioned itself against the patchwork education system of the German Empire, which was highly unequal, amounted to little more than rote memorization, and was directed according to the wants of local religious authorities (Wilson Reference Wilson1977, 40). Instead, the party demanded “universal and equal elementary education by the state. Universal compulsory school attendance. Free instruction in all education establishments. Religion should be regarded as a private matter” (40). Somewhat ironically, Karl Marx’s (Reference Marx, Friedrich, Lenin and Dutt1938) contemporary critique that free higher education “only means in fact defraying the cost of education of the upper classes from the general tax receipts” was often cited by proponents of tuition fees in Germany over 120 years later. The SPD continued to fight for a unified, universal, and secular public education system through the early twentieth century, though ultimately came up short in all its goals (Wilson Reference Wilson1977, 51).

These same inequalities and hierarchies largely carried over into the postwar Bundesrepublik, though social democratic critiques persisted. Attempting to stake a position between the defense of traditional hierarchy in higher education and the student activists who sought higher education’s radical democratization, Jürgen Habermas (Reference Habermas1970) delivered a lecture at the Free University of Berlin in 1967. He conceded that “universities must not only transmit technically exploitable knowledge, but also produce it,” at a time when, much like more contemporary globalization debates, education was seen as increasingly crucial to a dynamic and competitive economy. Nonetheless, he continued, universities must also (1) socialize students to enable prudent decision making and leadership; (2) “transmit, interpret, and develop the cultural tradition of the society”; and (3) “form the political consciousness of its students” (2–3). Taken together, the uniquely German roots of the human rights guarantee to education and the parallel debate over the social democratic nature of education, and higher education, in particular, constituted the structural context in which student activists chose to mobilize human rights law.

Vernacularizing the Human Right to Tuition-Free Higher Education: The Constitutive Impact of Human Rights on Movement Demands

While the analysis of discursive opportunity structures provides tools to understand the structural context in which activist groups adopt certain discursive frames, vernacularization studies help to bridge the gap between local legal contexts and international law. After all, while the history of Article 13 of the ICESCR had clear historical connections to Germany, there was not a similarly long history of invoking Article 13 in domestic policy disputes. In this study, while I find that activists seemed to believe genuinely in higher education as a human right, they were skeptical about the efficacy of human rights as an argument. By mobilizing human rights law, however, they sought to redirect blame for extant inequalities from those who presently benefited to the structural conditions that caused them. In the process, their demands came to encompass broader concerns than tuition fees.

Indeed, activists in the movement against tuition fees often invoked international human rights law as part of a broader conceptualization of higher education. In the 2006 Hattinger Erklärung, the second major declaration by the Action Coalition and the first after the 2005 Constitutional Court case, activists affirmed the demands of the Krefelder Aufruf and explicitly invoked the language of social democracy: “Tuition fees are part of a vision of society that wants to replace the civilizing achievements of the welfare state, participation, redistribution and fundamental equality of access to education with the radical market-fixated ideology of competition,” they argued, highlighting social democracy’s most central political-economic contributions.Footnote 13 In 2013, when only two states still charged tuition fees, the Free Association of Student Bodies released a statement that neatly tied the threads of social democracy and human rights law together:

[E]ducation must be accessible to all as the basis of the formation of a political consciousness, as the basis of a responsible society, and as the basis of individual welfare. That is not currently the case. The total elimination of tuition fees can only be a first step toward social justice in education. In the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (UN-Social Pact), the Federal Republic of Germany has committed to the guarantee that “higher education shall be made equally accessible to all, on the basis of capacity, by every appropriate means, and in particular by the progressive introduction of free education.” A ban of all forms of fees at the federal level would be the appropriate way to implement this commitment. (FZS 2013, n.p.)

While the social democratic goals of education played an important role in thinking about what the purpose of education is—as a place to form political consciousness, as the basis of a responsible society, and as the basis of the realization of one’s self—international human rights law offered a complementary guarantee (if only symbolic, in practice). In particular, international human rights law provided activists one culturally resonant way to frame the responsibility for the provision of these goals in higher education as belonging to the state, which has committed to the “progressive introduction of free education.” The adoption of human rights language—here used to strengthen the social democratic conception of higher education that had a long history in Germany—would in turn impact how activists themselves understood their struggle for public higher education by helping to expand their demands beyond mere maintenance of the status quo.

Movement actors were clear that they did not necessarily expect the language of human rights to win over public audiences. At a meeting on the state of tuition fees in 2019, where activists discussed two pending lawsuits alleging a violation of human rights law in the federal state of Baden-Württemberg after legislators introduced fees for non-EU international students, they expressed outright skepticism, resorting to economic arguments. Cendrese, a doctoral student who was representing the GEW, Germany’s largest education union, explained that “[f]or us education is a human right, but this emotional argument just doesn’t do it.” Phillip, a student activist who helped organize one of the lawsuits in Baden-Württemberg, echoed her thoughts, saying: “It is however unfortunate that one must always make an economic argument. It shouldn’t matter. [Education] is a fundamental right.” In an interview, Cendrese elaborated on her thoughts about the efficacy of international human rights law as an argument. She explained that the GEW was building on previous court decisions that highlighted the risk that tuition fees could introduce unacceptable social segregation—in particular, with reference to the ICESCR. When I asked her for whom she thought human rights arguments were likely to be effective, she expressed skepticism. Instead, Cendrese noted the argument was likely weakened by the nature of educational inequality in Germany. Of the people who study at university, she explained: “[W]hen we look at the statistics … they come out of households with high levels of educational attainment. So it’s not the poor folks who are studying in Germany.” She was careful to note that education itself plays a role in reproducing these inequalities—indeed, this was why she adamantly supported broadening access to free higher education—but that, nonetheless, this made the politics of free tuition challenging.Footnote 14

Cendrese struck at the heart of one of the strongest arguments in favor of tuition fees—namely, that despite idealistic declarations about education as a human right, the lived reality of working-class Germans often does not include a path to university education. But, as Cendrese argued and as activists have argued more broadly, the inequality is itself a problem, produced through the institutions, including education, of the state. The solution, then, lies not with eliminating important social institutions that disproportionately benefit some over others but, rather, with expanding those institutions to make real the promises of human rights to which the state committed itself. Stefan Bienefeld, a one of the leaders of the Free Association of Student Bodies who was active at the inception of the Action Coalition and, in 2003, the president of the National Union of Students in Europe, made a very similar point in an interview:

There are certain UN human rights treaties that say education should be free, or at least affordable. That was always the argument that one used, to say education is a human right and not a product—that education is not for sale—that was a classic slogan in this whole story. I believe the argument was important, even juridically, although certainly less meaningful there. I think it was an important argument also for the public to say, “hey, what we are doing is actually claiming a right. It is not a privilege, it isn’t. This is nothing special, and actually many more people should have the opportunity to go to university or to a technical college.” And I believe that this question arises because Germany has a relatively unjust education system. It has a lot to do with the school system, because sorting happens so early.Footnote 15

Although Bienefeld seems more positive about the role of human rights as a public argument than others, the key was in how it provided a legitimate counter-narrative to the arguments made by elites introducing tuition fees. Bienefeld’s insistence that “what we are doing is actually claiming a right” and that “[i]t isn’t a privilege, it isn’t,” is indicative of the power of legal consciousness to guide attribution of blame as well as the way in which such an argument can be framed for the public.

Whereas elite discourse had come to frame higher education as providing private economic benefits, and many politicians argued that tuition would improve financing and allow them to accommodate an expanding student body, Bienefeld explains how the language of human rights could be used to argue that states were violating the human rights of both current university students as well as those for whom access to university was already curtailed. Over time, activists came to expand their demands on the state to include redress of specific and persistent inequalities, in addition to the elimination of tuition fees, which could only make things worse, also expanding their coalition in the process to include a broad array of education interests. Nowhere was this clearer than the 2009 education strikes, which were organized by approximately 270 organizations across Germany, including school students, university students, labor unions, and the regional branches of major political parties. The education strikes are estimated to have attracted the participation of upwards of 270,000 people. At these events, though the same organizations that were central to the movement against tuition fees played an important role, demands were broad and inclusive of an array of interests—namely, unencumbered access to education (including by removing fees); an implementation of the Bologna Process reforms that avoided the over-bureaucratization of study courses and increased openings for Master’s students; the democratization of higher education (especially through shared governance structures that included students); and the general improvement of teaching conditions. The human rights conception of higher education was adopted in part because it shared much in common with social democratic visions of higher education; it also helped to expand and transform movement demands, as the language of human rights directed attention to inequalities in education, and to the state for its failure to address them. Much like Lynette Chua’s (Reference Chua2015) finding that international human rights law can play a role in developing an “oppositional consciousness,” its deployment by German activists played an important role in guiding the attribution of blame as well as the concrete demands for state action.

HUMAN RIGHTS MOBILIZATION AS STRATEGY: OPPOSING FEES ON ALL LEVELS

Rights Mobilization as Effective Resource or Distraction?

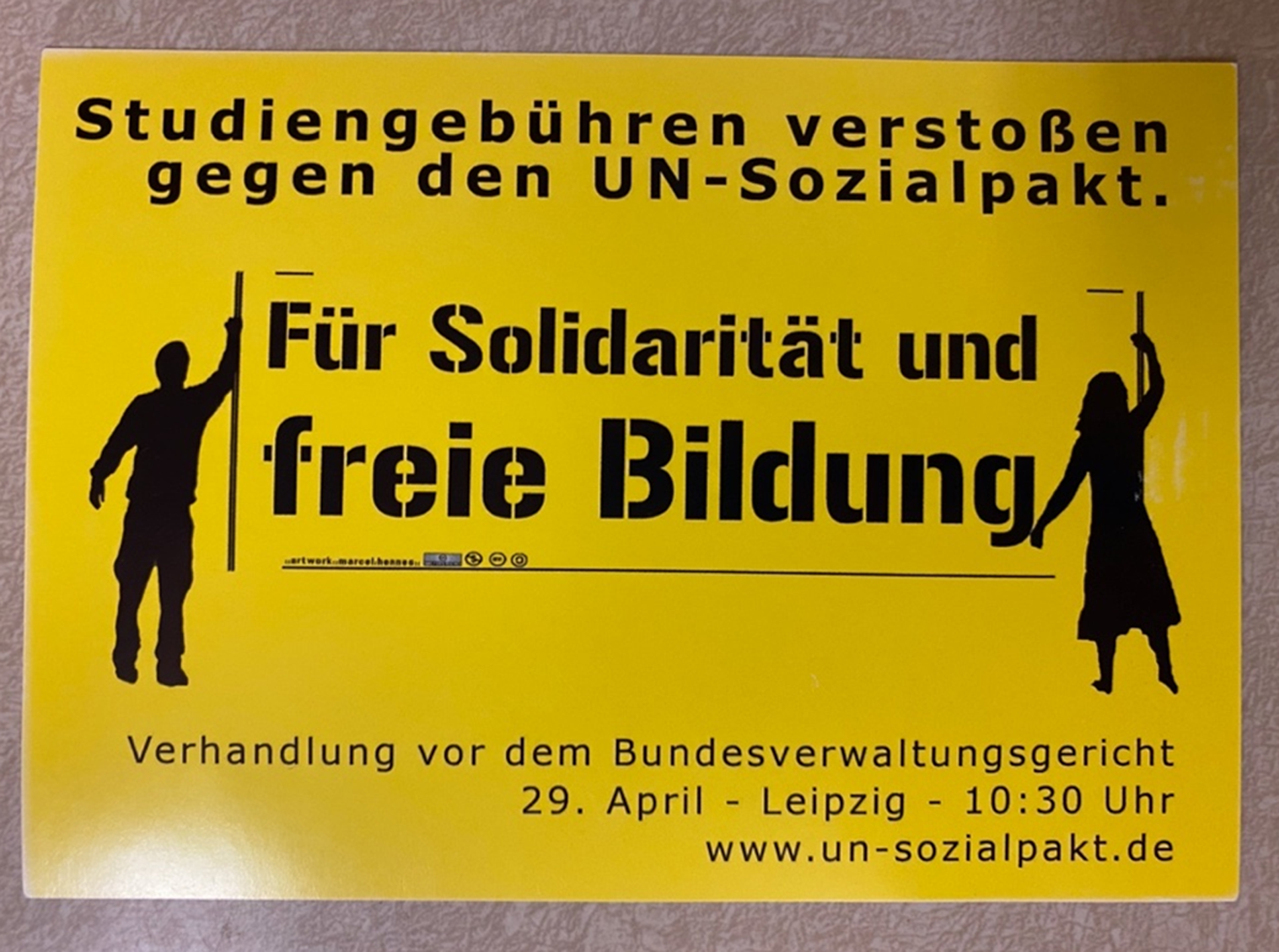

Although critics of legal strategies in social movements warn of the potential demobilizing effects of unfavorable court decisions, I found that in the German movement litigation was part of a broader attempt to mobilize law and support against tuition fees. Litigation produced events that generated media coverage and offered activists a tangible event to mobilize around; other types of movement activities, in turn, were organized to bolster litigation efforts. Even when litigation resulted in an unfavorable court decision, it enabled activists to elevate their rights claims and generated more discourse over the state’s obligations in the realm of higher education. In the 2009 case at the Federal Administrative Court, for example, where activists claimed in court that tuition fees violated their constitutional and human rights, litigation complemented, rather than displaced, other forms of movement activities. Figure 1 is a photograph of a sticker that was distributed as a sort of advertisement in the lead up to the proceedings before the court. At the top, one can see the phrase: “Tuition fees violate the UN social pact” (a colloquial name for the ICESCR), and underneath that a common motto from the movement that first came into use in 2006: “For solidarity and free education.” Here, as in the previous section, we see the convergence of the language of social democracy with the language of international human rights as they are adopted together to highlight their demands and direct those demands toward the state.

FIGURE 1. A sticker that was distributed in the lead-up to the 2009 Federal Administrative Court case, where student litigants challenged tuition fees as a violation of ICESCR.

Kurt, the current national director of the Action Coalition, emphasized the importance of activities other than litigation at the Action Coalition meeting in January 2019. One of the risks of bringing these questions to court, he explained, is that it might convince some people that they therefore do not have to go out on the streets and protest. But, as Kurt emphasized, “[i]f there’s societal pressure, then judges will pay attention.” And while societal pressure might help litigation efforts, litigation itself provided those types of mobilizing opportunities. In a discussion of ongoing litigation efforts, attendees talked about how even filing a case can be generative as journalists understand how to cover litigation. Likewise, movement activists used formal rights episodes as mobilizing opportunities, drawing broader attention to their campaign. Though major court cases like the one in 2009 were ultimately unsuccessful, it is notable that courts carefully balanced the arguments made by activists with the legitimate policy competences of states. In the 2009 decision, litigants opposing tuition fees constructed their legal case on the basis of the ICESCR’s guarantee of the progressive introduction of free higher education as well as on the ways in which tuition fees were likely to exacerbate existing inequalities. While the Federal Administrative Court ultimately took both arguments seriously, the court nonetheless attempted to explain why an outcome that protects the collection of tuition fees does not constitute a violation of the ICESCR:

According to the basic standard established in Art. 2 Par. 1 of the ICESCR, the contracting states are obliged to gradually achieve the full realization of the rights in the pact. … Even if one wanted to assume in favor of the plaintiff, that once a standard has been achieved in ensuring equal access to higher education according to the provisions of the pact it should be maintained, the contracting states, as accepted by the Social Committee, have considerable scope for regulation with regard to the introduction of tuition fees, so that they are not prevented from adopting systemic changes to the status quo. The North Rhine-Westphalian legislature, by raising universal tuition fees to achieve a legitimate public interest concern, did not abandon the principle of higher education free of financial exclusions. Rather, they have guaranteed student loans which, in their specific form, prevent insurmountable social barriers.Footnote 16

Indeed, even in sidestepping the specific legal claims raised by litigants, the court engaged seriously with the underlying concerns and the legitimate questions that those concerns raise for the realization of human rights. Somewhat narrowly, the court upheld the legislation implementing tuition fees on the ground that states are granted considerable leeway in attempting to achieve the full aims of the ICESCR. Although it is not clear whether the court reasoned as it did because of movement pressure, the work of the court was certainly complicated by mass mobilization around this issue at the time, culminating only months after the court’s decision in the nationwide education strike, in which several hundred thousand students across all levels of education reportedly participated. At the very least, the court must have been cognizant of the political implications of its decision on the question of tuition fees and human rights.

Fredrik, another former national director of the Action Coalition and current representative chairman for the GEW in Hamburg, contemporaneously completed his dissertation on the discourse and tactics of the social movement against tuition fees. When I asked him whether unsuccessful litigation was damaging to the overall goals of the movement—whether, for example, it might foreclose certain possibilities or lines of argument—he seemed skeptical. He acknowledged that many were critical of the choice to expend resources on litigation strategies but emphasized “that we really attempt to oppose fees on every level possible, and for exactly that reason we were always involved in litigation efforts. To put it simply, we had to use every possibility—and that’s what we did to significant effect—even if we sometimes lost or it cost money.”Footnote 17

For Fredrik, legitimate concerns with court-centered legal strategies were somewhat beside the point as the movement was not narrowly focused on litigation. Student organizations were willing to support litigation in the hopes that it might provide one avenue to challenge the introduction of fees, but they did not expect neat victories. In fact, this commitment to fighting on every level became something of a motto for the movement. Figure 2 is a poster from 2007 that includes a number of images of people—both contemporary and historical—who opposed tuition fees, as the large title at the top tells us. At the bottom of the poster are several symbols, including a logo from the 2005 “Summer of Resistance” that declares: “Education is a human right!” as well as the 2006 logo: “For solidarity and free education!,” which is another convergence of human rights mobilization and social democratic talk. The subheading of the poster includes three verbs: demonstrate, litigate, and boycott. For movement activists, fighting with every means on every level was centrally important in the effort to prevent and turn back the introduction of tuition fees.

FIGURE 2. A poster advertising the goals and work of the Action Coalition against tuition fees.

Generating Political Pressure through Human Rights Mobilization

In a January 2007 newsletter, the Free Association of Student Bodies announced that it had decided a month earlier to challenge new tuition laws at the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva (FZS 2007b). That October, the Free Association of Student Bodies issued an invitation to an event that would feature Andreas Keller, a leader of the GEW education union’s section for higher education and research, and Wilhelm Achelpöhler, a Münster-based lawyer who led litigation efforts in the movement against tuition fees and who continues to challenge tuition fees for international students today (FZS 2007a). There, they publicly released a report of observations that they would be submitting to the UN Human Rights Commissioner, outlining their case for why they understood tuition fees to violate Germany’s commitments to the ICESCR. As one press report at the time explained the context, the report was issued the same month that the High Administrative Court for the state of North Rhine Westphalia had rejected student litigants’ claims around Article 13(1) of the ICESCR—a case that, on appeal, would become the 2009 Federal Administrative Court case that concluded in much the same way (Wilkens Reference Wilkens2007). In the report’s cover letter, the authors write to members of the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights at the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, explaining that, despite the committee’s recommendation “that Germany commence a reduction in student fees in its national provisions on higher education with the aim of eliminating them altogether,” “the State Party has not followed” the recommendations in its 2001 periodic report (at the time, these fees were narrowly targeted). In the report, the GEW and the Free Association of Student Bodies outline the obligations created by the ICECSR as well as its applicability in domestic law in Germany. They then spend considerable time exploring inequality in German higher education: first, as a result of the “dual education system” that tracks students and, second, along demographic lines like gender and income. The section of the report concerned with inequality of access concludes that

Access to higher education in Germany is still strongly influenced by social origin. The link weakened, especially during the 1970s, probably due above all to the abolition of lecture charges (tuition fees) and the adoption of the Federal Training Assistance Grant (BAföG), which originally provided a full grant. But this process of opening up higher education from a financial perspective was not pursued. First of all BAföG was gradually devalued, … and since the judgment by the Constitutional Court in January 2005, tuition fees have been introduced in various federal states. This is too recent for detailed impact data, but since the Court’s ruling there has been a massive drop in the percentage of students taking up their option to study, which means that fewer and fewer school-leavers entitled to higher education are actually entering it. Financial motives play a part in this. Surveys … show that women and people from families with lower education attainment have been particularly affected. (Achelpöhler et al. Reference Achelpöhler, Konstantin, Klemens and Andreas2007, 26)

The report ultimately concludes that neither the federal or state governments of Germany “are complying with the obligations derived from ICESCR. This applies in particular to Article 13 (2 c) and (2 e),” and the two organizations therefore have requested a formal reprimand of the German government (31–32). Here, as elsewhere, the claim of a human rights violation is bolstered by outlining the ways in which tuition fees make extant inequality even worse. The report resulted in a non-binding reprimand of German practices by the commissioner’s office. I asked Andreas Keller, who today is the representative head for the GEW’s higher education and research division, about the origination and goals of the report. He explained that the GEW was looking for any avenue they could to challenge fees, and it occurred to them that the language in Article 13 already existed, as did a mechanism to file a formal complaint. The GEW and the Free Association of Student Bodies were able to demonstrate in a 2008 hearing that tuition fees lead to adverse effects, particularly for the most disadvantaged students:

The end effect was that tuition fees in Germany were criticized, but unfortunately the recommendations were non-binding, so that the federal government did not immediately direct attention to the state governments in 2008, and it wasn’t until later that the fees were once again eliminated. If I’m to be honest, the committee’s recommendation probably played a relatively small role, as it seemed to play little role in the domestic political debate. But nonetheless we had the respectful success of having it clearly stated that the introduction of tuition fees violated ICESCR.Footnote 18

For Keller, it was not clear whether or not the modest victory from the UN played a significant role in the elimination of tuition fees, but it was part of the fight-on-every-level ethos that guided movement organization. Human rights is used here to attribute blame for extant inequalities to the practices of the state, and the non-binding reprimand provided support for these arguments from an external human rights monitor. I asked him whether legal arguments like the one made in the report to the UN or in the court cases were helpful in the public debate over tuition fees. While Keller said that such arguments “were definitely important,” he thought that “[m]ore important still is the way in which it’s actually employed politically.” Significantly, he continued, modest victories “leave it hanging there that these policies are not totally clean, that they violate fundamental rights, human rights. That it was left hanging was very important to the public debate, but legal strategies alone would not suffice. Questions of rights are always questions of power if there isn’t also a political campaign, political pressure.”

CONCLUSION

This article has sought to engage with theoretical understandings of legal mobilization and human rights discourse in the context of welfare state retrenchment, directing our attention to bottom-up efforts to resist the privatization of social institutions. I have built upon the work of socio-legal scholars who have pushed back against those who question the value of human rights in domestic policy disputes and have demonstrated the complex ways in which human rights can matter (Chua Reference Chua2015; Kahraman Reference Kahraman2018). I have showed that German activists who were skeptical about the public-facing efficacy of human rights arguments nonetheless also used the language of human rights to redirect the most potent criticisms of free tuition toward the state. Human rights were a readily available discursive opportunity structure that complemented other forms of culturally resonant discourse; they were also a tangible legal resource that activists could mobilize formally to generate attention and bolster their argument. Through the process of translating the human rights argument to the local context, the activists in my study expanded the scope of movement demands against the state to better address educational inequality in the country and generated media coverage that increased public pressure on policy makers.

Thinking about human rights as not just a potential legal instrument but also a discursive opportunity structure provides important analytical leverage for thinking about the efficacy of human rights strategies in domestic contexts across cases as well as why these strategies may be used in some contexts and not in others. For example, higher education as a human right does not feature prominently in debates in Great Britain or the United States. Building on Ferree’s (Reference Ferree2003) framework, we can make sense of this absence through an analysis of the legal and cultural context. In the United States, for example, although most states have recognized education as a fundamental right (Zackin Reference Zackin2013), the US Supreme Court refused to recognize a federal constitutional right to primary and secondary education in its 1973 decision in San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez.Footnote 19 While American activists certainly can draw on the promises of human rights, and may well do so in ways that Ferree (Reference Ferree2003) would consider “radical” in an American context, the employment of human rights over social policy has little institutional history, and the United States has not even adopted the ICESCR that was featured so prominently by German activists. But even in contexts where such frames may be “resonant,” their efficacy still largely depends on how they are understood and employed by activists.

To be clear, human rights were one of many arguments used by the German movement against tuition fees, employed in concert with other strategic efforts. Faced with trends toward privatization in higher education—and deliberate attempts to remodel European higher education systems to compete directly with American institutions—activists in Germany organized and mobilized early, establishing campaign fronts years before tuition fees were even introduced. The human rights argument was initially employed as a complementary legal guarantee to the largely social democratic demands German activists generated around free higher education. Over time, it came to be used as a way to counter arguments that highlighted inequality in higher education and became essential to a broader framing of demands in the area of education writ large. Moreover, far from directing limited resources away from other, perhaps more useful, strategic efforts, the formal mobilization of human rights law was always part of broader campaigns, not an end in itself. In most states, fees were reversed legislatively following elections after years of demonstrations, occupations, disruptions, and lawsuits, as state legislators reacted to a sizable and well-mobilized constituency.

Finally, it is worth considering how we should understand this all in the context of welfare state retrenchment. Scholars should direct their attention to the ways in which retrenchment is received or resisted on the ground. For one, it is possible that if we adopt a top-down bias we might miss bottom-up efforts to resist retrenchment, especially in cases where retrenchment is successful. Perhaps more importantly, we might also lose the opportunity to understand how people on the ground understand retrenchment, the state’s social responsibilities toward its people, and how retrenchment and resistance to such retrenchment can reshape politics and participation in fundamental ways.