INTRODUCTION

In Darfur and the Crime of Genocide, John Hagan and Wenona Rymond-Richmond (Reference Hagan and Rymond-Richmond2009) develop a model of genocide that causally links macro-level conditions via micro- and meso-processes to macro-social outcomes, most importantly that of a genocidal state (see also Hagan and Rymond-Richmond Reference Hagan and Rymond-Richmond2008). We refer to this as the Darfur model. Elsewhere, Hagan (Reference Hagan2003) examines criminal prosecutions of mass atrocity crimes in the case of the former Yugoslavia. Throughout, Hagan and his collaborators are mindful of a substantial gap between legal and social science modes of thinking about genocide (for example, Hagan and Rymond-Richmond Reference Hagan and Rymond-Richmond2009, 107). Their skepticism is in line with literature on judicial responses to mass violence that highlights the selectivity of narratives generated by court proceedings (Pendas Reference Pendas2006; Marrus Reference Marrus, Heberer and Matthäus2008; Savelsberg and King Reference Savelsberg and King2011). Aware of such selectivity, Hagan (Reference Hagan2003) is nevertheless able to draw information from legal proceedings that advances social scientific insights.

This article contributes to both foci of Hagan’s work on genocide. Following a summary of the Darfur model, it asks, first, how the causal factors and processes that Hagan and Rymond-Richmond identify for the case of Darfur play out in the Rwandan genocide. What are we to conclude about the external validity of the Darfur model versus the historical specificity of genocide? Second, we explore what aspects of knowledge generated by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) can enhance social scientific insights. We are simultaneously mindful that judicial narratives address or select out factors highlighted in the Darfur model, and we address such selectivity.

THE TWICE-TOLD STORY OF GENOCIDE: SOCIAL SCIENCES VERSUS CRIMINAL TIALS

The phenomenon of genocide is ancient, but the concept is historically new. The term dates back to the work of Raphael Lemkin (Reference Lemkin1944), reflected prominently in his 1944 book Axis Rule in Occupied Europe and the 1948 United Nations Convention for the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Genocide Convention).Footnote 1 By now, scholarship and popular literature fill libraries on the topic. Work by historians, political scientists, and legal scholars dominates (for example, Horowitz Reference Horowitz1981; Browning Reference Browning1998; Hilberg [Reference Hilberg1961] 2003; Weitz Reference Weitz2003; Friedlander Reference Friedlander2007; Meierhenrich Reference Meierhenrich2014). Sociologists and criminologists lagged behind, despite notable early exceptions (for example, Hughes Reference Hughes and Becker1963; Fein Reference Fein1979). Work on genocide in the latter fields, however, has gained momentum in recent decades, and it has provided new insights. This applies to research on genocide itself (for example, Kramer and Michalowski Reference Kramer and Michalowski2005; Steinmetz Reference Steinmetz2007; Nyseth Brehm Reference Nyseth Brehm2014, Reference Nyseth Brehm2017; Rafter Reference Rafter2016) and to scholarship on the legal, political, and cultural processing of genocide (Douglas Reference Douglas2001; Hagan Reference Hagan2003; Alexander et al. Reference Alexander, Eyerman, Giesen, Smelser and Sztompka2004; Giesen Reference Giesen2004; Savelsberg Reference Savelsberg2015, Reference Savelsberg2021; Savelsberg and Nyseth Brehm Reference Savelsberg and Nyseth Brehm2015; Olick Reference Olick2016).

Hagan (Reference Hagan2003) played a central role in bringing the topic of genocide to sociological criminology (see also Hagan and Rymond-Richmond Reference Hagan and Rymond-Richmond2008, Reference Hagan and Rymond-Richmond2009). Together with Rymond-Richmond, he argued that scholarly thought on the issue cannot be limited to the legal categories developed to ease the prosecution of the crime of genocide in light of substantial legal and political adversities (Hagan and Rymond-Richmond Reference Hagan and Rymond-Richmond2009, 114). He rightly insists that concepts such as “joined criminal enterprise” or “criminal organization,” originating in the notion of conspiracy derived from US law and core tools in proceedings such as the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg (IMT) and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), do not reveal the social dynamics that actually underlie genocidal processes. This argument relates closely to the literature on the specific institutional logic of criminal law and its divergence from the logic of social science. It matters especially because of the epistemic power of judicial narratives in the realm of media reporting, public perceptions, and collective memories (Pendas Reference Pendas2006; Marrus Reference Marrus, Heberer and Matthäus2008; Savelsberg Reference Savelsberg2015, Reference Savelsberg2021).

The Darfur Model

Social science has long addressed micro- (Waller Reference Waller2007), meso- (Browning Reference Browning1998), and macro-social (Bauman [Reference Bauman1989] 2000) contributors to genocide. In Darfur and the Crime of Genocide, Hagan and Rymond-Richmond (Reference Hagan and Rymond-Richmond2009) incorporate these levels of analysis into an integrated, multi-level theory. They are mindful of historical context, leading from the Sultanate Darfur via colonial rule to Darfur’s incorporation into an independent Sudan. They highlight the historically fluid relationships between various groups sharing this region of Sudan: Arab tribes, mostly nomads, on the one side, and sedentary agricultural groups—today classified as Black Africans—on the other, including the Fur, Masalit, and Zaghawa. They recognize the desertification that began in the mid-1980s, resulting in famine and disputes over land and water. Such times of conflict result in the “unmixing” of groups (Brubaker and Laitin Reference Brubaker and Laitin1998) and in intensified “social rigidity” (Comaroff and Comaroff Reference Comaroff and Comaroff1997). Conflicts became deadlier when Libyan president Muammar Qaddafi promoted Arabization and fed arms into the Darfur region. Domestic Arabization campaigns under Sadiq al-Mahadi, and—yet more decidedly—under Omar al-Bashir, in the years after his 1989 military coup, further intensified the conflict. In reaction, in the early 2000s, “Black” rebel groups took up arms, specifically the Justice and Equality movement and the Darfur Liberation Front, later renamed the Sudan Liberation Army/Movement. The government, supported by Janjaweed militias, which it mobilized and equipped with military hardware, responded with brutal force. It directed its aggression not just against the militants but also against the civilian population. Half of the six million inhabitants of the region were displaced. Many perished along the way, and those who survived the attacks and expulsions sought refuge in internally displaced people or refugee camps. Hagan and Alberto Palloni (Reference Hagan and Palloni2006) calculate a death toll of approximately three hundred thousand.

Screening the criminological literature for building blocks toward an explanatory model, Hagan and Rymond-Richmond (Reference Hagan and Rymond-Richmond2009) highlight differential organization, with its focus on organization more or less in favor of crime (Sutherland Reference Sutherland1947; Matsueda Reference Matsueda2006); collective efficacy, considering the capacity of communities to achieve shared goals—noble or destructive ones (Sampson Reference Sampson2004); social efficacy, addressing the ability of individuals to mobilize others in the pursuit of shared goals (Matsueda Reference Matsueda2006); and, finally, collective mobilization in which “solutions” are inspired by notions of “us versus them.” This mobilization is enhanced by status frustration and lubricated by neutralization techniques. Applying these concepts to Darfur generates a story in which the state, with its military and security apparatus, mobilized the leadership of a genocidal criminal organization (Janjaweed), defined Blacks as lesser humans (us versus them), and thus provided a “vocabulary of motive” associated with neutralization strategies (Hagan and Rymond-Richmond Reference Hagan and Rymond-Richmond2009, 120–21). The state finally used the social efficacy of its agents to advance racialized definitions. It found receptivity among Arab herders who were suffering from diminishing resources and resulting status frustration.

The model culminates in a “critical collective framing approach,” masterfully captured in a macro-micro-meso-macro-model, adapted from James Coleman’s (Reference Coleman1990) Foundations of Social Theory. Applying this model to Darfur, Hagan and Rymond-Richmond (Reference Hagan and Rymond-Richmond2009) begin at the macro level, where they locate a state-led Arabization ideology, supremacism and dehumanization, and competition over land and resources. These macro-forces contribute, at a lower level of aggregation, to a solidification of socially constructed and locally organized groups. Group members internalize new group-specific identities, a process that, in the context of militant group action, results in collectivized racial intent. The yelling of racial epithets during the attacks on villages expressed, and intensified, that intent. An analysis of geo-clusters indeed reveals impressive correlations between the reporting of epithets and the rates of killings and sexual violence. Micro- and meso-level processes finally feed back to the macro-level: a genocidal state and genocidal victimization.

The Logic of Criminal Law

Hagan and Rymond-Richmond (Reference Hagan and Rymond-Richmond2009) contrast their social scientific model with one based on judicial reasoning, including the use of legal categories. Their account begins after the International Commission of Inquiry in Darfur had delivered its report to the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) in 2005, which was when the UNSC referred the case of Darfur to the International Criminal Court. Initially, after two years of investigation, then Chief Prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo charged the Sudanese government minister Ahmad Harun and militia leader Ali Al-Rahman (aka Ali Kushayb) with war crimes and crimes against humanity. He described them as “part of a group of persons acting with a common purpose.” The wording of these charges is rooted in the notion of “conspiracy” in US law, “criminal organization” at the IMT, and “joint criminal enterprise” at the ICTY (Meierhenrich Reference Meierhenrich2006). Simultaneously, the prosecutor saw “the whole state apparatus … [involved in the] organization, commission and cover-up of crime in Darfur.” This sort of legal reasoning eventually leads up the hierarchy of the state, culminating in the prosecution of (then) President Omar al-Bashir. In 2008, Moreno-Ocampo charged al-Bashir with war crimes and crimes against humanity and, in 2010, with genocide. Hagan and Rymond-Richmond (Reference Hagan and Rymond-Richmond2009) urge social scientists not to be content with the legal categories that the prosecutor used in his indictments. They suggest a move away from asking: “What legal doctrines offer precedent to cope quickly with the challenge?” to a new question: “What influence do participants in such criminality actually exercise over one another, through what organizational devices and interactional dynamics?” (107). It is in response to this question that they develop the causal model outlined above.

Sociologists may further contrast their strife for social scientific explanation with the basic categories and institutional logics of the criminal law. History told by criminal proceedings indeed differs from accounts produced by social scientists. Criminal law, after all, is subject to a particular set of institutional rules. First, criminal law focuses on individuals. Social scientists instead also consider social structure and broad cultural patterns as precursors of mass violence. Second, criminal law is rightly constrained by specific evidentiary rules. The evidence that historians or journalists use may be inadmissible in criminal court. Third, criminal law is constrained by particular classifications of actors, offending and victimization. It may be blind, for example, to the role played by bystanders, who are essential contributors from a social science perspective. Fourth, criminal law applies a binary logic. Defendants are guilty or not guilty, provided that actus reus and criminal intent can be proven. Social psychologists consider more differentiated categories, and philosophers, historians, and even some victims see “gray zones” among both perpetrators and victims (Levi Reference Levi1988; Barkan Reference Barkan2013). Wise jurists are aware of the limits of criminal law as a place for the reconstruction of history (on the judges of the Eichmann trial, see Osiel Reference Osiel1997, 80–81; on the ICTY, see del Ponte Reference Del Ponte2008).

Social theorists and empirical researchers confirm these concerns. Jeffrey Alexander and colleagues (Reference Alexander, Eyerman, Giesen, Smelser and Sztompka2004) observe that linguistic action, through which the master narrative of social suffering is created, is mediated by the nature of institutional arenas that contribute to it. Clearly, some claims can be better expressed in legal proceedings than others can. Some carrier groups have privileged access to law, and they repeatedly seek legal recourse (on “repeat players,” see Galanter Reference Galanter1974). Further, some classifications of perpetrators, victims, and suffering are more compatible with those of the law than others are. Law’s construction of the past, the kind of truth it speaks, the knowledge it produces, and the collective memory to which it contributes is thus always selective (Pendas Reference Pendas2006; Marrus Reference Marrus, Heberer and Matthäus2008). Consequently, representations of mass atrocities generated in the context of criminal court proceedings differ profoundly from social science accounts and explanations. They also leave stronger traces in the public perception and the collective memory of these events, testimony to the particular epistemic power of criminal court proceedings (Savelsberg Reference Savelsberg2015, Reference Savelsberg2021).Footnote 2

John Hagan is aware of the selectivity of judicial narratives. He nevertheless illustrates how trials and preceding investigatory work generate information that social science inquiry can put to effective use. For example, his work on the ICTY shows how military intercepts, traced by investigators, provide insights into chains of command and into coded language, a core tool in the execution of genocide (Hagan Reference Hagan2003). Further, satellite images help with the identification of mass graves, and the subsequent opening of such graves delivers evidence on the forms of killing and accompanying cover-up strategies. Hagan’s work also shows how court testimony by surviving witnesses provides insights into the organization of rape campaigns in Bosnian towns. Hagan puts such information to use as he interweaves his analysis of the ICTY and the unfolding of the mass atrocity crimes committed in the wars of the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s. In short, despite social scientists’ caution regarding criminal court narratives’ ability to speak to the ontology of crime, Hagan’s work shows that evidence produced in judicial proceedings can still advance sociological insights into the unfolding of mass atrocity crimes.

THE CASE OF RWANDA: CAUSALITY IN SOCIAL SCIENCE LITERATURE AND ICTR KNOWLEDGE

Shifting our attention to the Rwandan genocide of 1994, we first read the social scientific literature on the Rwandan genocide against core categories of Hagan’s Darfur model, exploring overlaps and deviations that speak to generalizability versus historical specificity. We then contrast the resulting social science narrative against that which is generated by the ICTR to simultaneously explore the deviations of the court narrative from a social scientific logic and the potential contributions of the court proceedings to social science explorations of genocidal processes.

Rwanda in the Social Science Literature

The assassination of Rwandan President Juvénal Habyarimana in April 1994 was the immediate precursor of the Rwandan genocide. Following the assassination, extremist forces of the government took control of the state. In the following one hundred days, over eight hundred thousand members of the Tutsi minority group were killed (Gourevitch Reference Gourevitch1998). Scholarship identifies as the responsible actors the Hutu extremist regime and groups of killers whom it mobilized. The state also targeted many Hutu civilians and moderates, especially those they thought stood against the execution of the genocide (Prunier Reference Prunier1995; Mamdani Reference Mamdani2001). The following pages apply Hagan and Rymond-Richmond’s theoretical model, built on the experience of Darfur, to the Rwandan case. The analysis shows that similar (but not identical) factors mobilized actors in both cases.

State and Racialization

In Rwanda, as in Darfur, origins of the process can be identified at the macro-level. Independence after decades of colonial rule had cemented a shift in power within the Rwandan state. Under colonial rule, first German, then Belgian, officials racialized ethnic identities and reinforced preexisting ethnic hierarchies, especially Tutsi-dominated political authority, in their system of indirect rule (Newbury Reference Newbury1988). This strategy changed social dynamics in the precolonial system, where Tutsi and Hutu constituted relatively fluid identities. Indeed, as Catharine Newbury (Reference Newbury1988, 212) concludes in her seminal study: “Ethnicity in Africa is not primordial. It is a historically, socially constructed category that can experience significant change. Changes in ethnic identities and solidarities are related to other broader societal transformations.” This insight proved true again when independence arrived in 1962, and, with it, Rwandan governance changed to a system of majority rule, thus shifting political control to the once-marginalized, but significantly larger, Hutu ethnic group (Prunier Reference Prunier1995; Mamdani Reference Mamdani2001). In the “Hutu Revolution” of the early 1960s, tens of thousands of Tutsi civilians were targeted and killed. Many survivors fled to neighboring Uganda.

The mass killings of the 1960s were only the start of decades of state-sponsored violence and discrimination of ethnic Tutsi in Rwanda. Only Hutu could hold positions of power and prestige in state and educational institutions, and state actors regularly killed Tutsi civilians (Prunier Reference Prunier1995). Many memoirs of Tutsi survivors speak to the dehumanization promoted by state institutions throughout these decades. In Cockroaches, Scholastique Mukasonga (Reference Mukasonga2006) speaks to anti-Tutsi discrimination throughout her education, culminating in her eviction from school. Numerous survivors share similar testimony in We Survived: Genocide in Rwanda, a collection of testimonies gathered by the Kigali Genocide Memorial (Whitworth Reference Whitworth2006). These survivors speak to forced migration, political targeting, and violence that they and their families experienced in the decades leading up to the genocide. The process resembled what Hagan and Rymond-Richmond (Reference Hagan and Rymond-Richmond2009) described for Sudan as a state-led Arabization ideology, supremacy, and dehumanization of minorities.

Also like in Sudan, anti-minority (here, anti-Tutsi) propaganda campaigns supported violence and discrimination. In the years leading up to the 1994 genocide, Kangura magazine published extensive anti-Tutsi content. The “Hutu Ten Commandments,” for example, denounced Hutu who married, befriended, or did business with Tutsi. Kangura also featured political cartoons, often depicting Tutsi as cockroaches (Gourevitch Reference Gourevitch1998; Des Forges Reference Des Forges1999). In addition, propagandist media played into colonial tropes that characterized Tutsi as taller, lighter skinned, and with thinner features, using these stereotypes to claim that Tutsi were more European than Hutu, whom they depicted as the original inhabitants of Rwanda. The Radio Television Milles Collines (RTLM) station infamously propagated anti-Tutsi messaging in a broadly consumable way and featured music and speakers that promoted anti-Tutsi narratives (Des Forges Reference Des Forges1999).

In short, in the case of Rwanda, anti-Tutsi campaigns by the Hutu-dominated state was partially a reaction to earlier—colonial power-promoted—control by the Tutsi minority over the Hutu majority (Newbury Reference Newbury1988, 208–9). Despite such specificity in historical background, both the Rwandan and the Darfur genocides were preceded by state-sponsored racialization campaigns, directed at the minority group. The parallels, and support for the Darfur model, do not end there, as the following section shows.

Differential Organization

Parallel to Hagan and Rymond-Richmond’s (Reference Hagan and Rymond-Richmond2009) observations about the Sudanese state equipping Janjawiid militias with ideology and military hardware, Rwandan state actors also began arming and training Hutu youth militia, known as the Interahamwe. The Interahamwe were formally not affiliated with the ruling state political party. Yet the two were significantly intertwined through a national-level committee. Part of a hierarchical system of violence, the Interahamwe had their strongest, best-trained forces in the capital of Kigali, though they were also represented at the regional level. The state and military would run training and operations preceding and during the genocide, supported to varying degrees by civilian forces. Once the genocide began, the state and the Interahamwe often committed violence side by side under the direction of government forces (Des Forges Reference Des Forges1999), which is another parallel to the Janjawiid-military cooperation in Darfur. Hollie Nyseth Brehm (Reference Nyseth Brehm2017) found that collaboration between these local and state actors enhanced rates of killing. Areas of Rwanda with stronger ties to the state had higher rates of killing, though local-level factors like community integration could also alter rates of killing. Jean Paul Kimonyo (Reference Kimonyo2016) also examined localized dimensions, citing social and economic histories along with political dynamics that cultivated support or dissent for the Habyarimana and genocidal regimes, as key factors in cultivating popular participation. Omar McDoom (Reference McDoom2020) also explores these localized differences in political power—national leaders from the genocidal regime often had to negotiate with local leaders, and varying levels of pre-genocidal political alignment could heighten or expedite this process. In sum, differential organization in favor of violence played out in both Sudan and Rwanda, further supporting the generalizability of the Darfur model.

Struggle over Resources and Intensifying Group Boundaries

Literature on Rwanda describes other macro-level factors that resemble those at work in Sudan, especially economic and resource challenges at the time of the genocide. The 1980s had seen coffee prices fall, intensifying economic strain in the already poor country (Prunier Reference Prunier1995). Resulting economic hardship may not have been as grave as that emanating from the desertification of the Sahel zone in the Darfur region of Sudan, but, in combination with the earlier-cited macro-factors, it provided fertile ground for violence. State-sponsored discrimination and dehumanization exacerbated existing tensions along group lines. The identities of Tutsi and Hutu existed long before the genocide, even before colonial intervention. Hutu and Tutsi were simultaneously clan and economic identifiers. Tutsi generally held positions of power, though integration between Hutu and Tutsi was strong (Des Forges Reference Des Forges1999). Despite such integration, however, state-sponsored hate campaigns, like in Sudan, resulted in the hardening of identities, the drawing of ever-tighter boundaries between the groups.

In both Darfur and Rwanda, intensified identification with one group, and increasingly rigid boundaries to the other, played a crucial role in the unfolding of the killings. Jean Hatzfeld (Reference Hatzfeld2003) charts the impact of the roles of ideology, dehumanization, and group boundaries. Particularly at the early stages of violence, anti-Tutsi rhetoric and inter-group dynamics were essential mobilizers for many of Hatzfeld’s research subjects. As one of Hatzfeld’s respondents reflects, “[w]e no longer saw a human being when we turned up a Tutsi in the swamps. I mean a person like us, sharing similar thoughts and feelings” (47). Parallel to the experience in Darfur, and in line with Hagan and Rymond-Richmond’s (Reference Hagan and Rymond-Richmond2009) model, the constructed division between Hutu and Tutsi was central in organizing the extremist genocidal state. Government actors used anti-Tutsi rhetoric to promote their own power in the context of civil war and the threat of Tutsi rebel forces. They condemned the Rwandan Patriotic Army as Tutsi invaders while criticizing the Rwandan government under President Habyarimana for considering peace talks. Hutu supremacy was central to their power and goals of governance (Gourevitch Reference Gourevitch1998; Des Forges Reference Des Forges1999).

When extremist forces in the Rwandan government overtook the state, the genocide began in full force. Roadblocks appeared in the capital of Kigali within hours, with state forces ordered to kill Tutsi civilians who attempted to pass through. Military, police, and the Interahamwe were repurposed under the new regime to mobilize for the genocide, targeting moderate state actors whom they deemed unfriendly to the new government. These groups had been prepared and trained under the pre-coup administration, and ethnic violence had been widespread before the genocide. Yet under the new administration, violence was transformed. State forces mobilized groups and institutions, including ones that generally played no role in violence or security (like groups of farmers) into genocidal instruments. A governance hierarchy, helmed by leaders at the highest level, mobilized hundreds of thousands of Rwandans to participate in the violence (Des Forges Reference Des Forges1999; Mamdani Reference Mamdani2001; Straus Reference Straus2006).

In short, tightening resources intensified inter-group tensions, which were further enhanced by government propaganda. This process again is in line with the Darfur model, but the Rwandan case also reveals distinctions and historical specificity, as the following section shows.

Group Dynamics and Genocidal State

The previous sections confirm the validity of Hagan and Rymond-Richmond’s (Reference Hagan and Rymond-Richmond2009) focus on the role of power and control, specifically the hierarchical, state-sponsored organization of genocidal violence. Within such systems, ideology and belief are crucial drivers. Elite entrepreneurs motivate their subordinates through invocations of ideology. Followers enhance emotional energy through the yelling of racial epithets during attacks in Darfur. This shared commitment as a driver of collective action and efficacy is clearly documented for Rwanda as well. Importantly though, despite substantial confirmation of the Darfur model by scholarship on the Rwandan genocide, many perpetrators in Rwanda were not, or were only marginally, affected by racist ideology. Scott Straus (Reference Straus2006), in The Order of Genocide: Race, Power, and War in Rwanda, provides a crucial example. Straus surveyed and interviewed rural Hutu perpetrators, often the target of local or state officials for mobilization. Among these Hutu, it turns out, the level of anti-Tutsi ideology was remarkably low, and few directly engaged with state-sponsored, anti-Tutsi propaganda. Many interviewees instead reported that they had not heard of infamous examples of mobilizing discriminatory ideas such as the “Hutu Ten Commandments” or the “Hamitic Myth,” which classified Tutsi as non-Rwandan in origin. Strikingly, over 64 percent of his 209 respondents claimed coercion as their primary motivator for participating in killings during the genocide. While the mobilizers themselves may have used racial epithets during the killings, these Hutu perpetrators claimed fear of fees, shame, or physical harm as the reason they killed. This finding is echoed in calls for Hutu perpetrators to engage in “work” as a euphemism for killing. Such vocabulary is dehumanizing, but it is sanitizing rather than emotive or inflammatory. A smaller number of perpetrators in Straus’s study also claimed the desire to rescue family members or friends as motivators to participate in the violence.

Even where racial hatred was the initial motivating force, words by a perpetrator interviewed by Hatzfeld (Reference Hatzfeld2003, 47) illustrate the transformation of affective sentiments into routine: “At the beginning we were too fired up to think. Later on we were too used to it.” Indeed, in Rwanda, as in Darfur, “at the beginning” refers to structure, “fired up” to micro- or meso-contexts of social action, and “used to it” to newly emergent structures. In line with this intermingling of racial hatred, routinization, and simple strife for self-protection, Aliza Luft (Reference Luft2015) shows substantial complexity in the motivation of the genocidal actors in Rwanda. Many individuals engaged in both killing and rescuing behavior during the genocide, and many did so strategically to avoid suspicion or being cast as Tutsi sympathizers. Luft’s observations align with insights by Lee Ann Fujii (Reference Fujii2009), who finds, through her study of local ties and group dynamics in Rwanda, that hatred was often based on personal grievances, not directed at the other ethnic group as a whole. Consequently, she identifies ethnic hatred less as a cause and more as a consequence of genocidal action, albeit legitimated by scripted ethnic claims. Mobilization for killing was enhanced by unusually dense social networks and resulting pressures toward co-optation, to which Rwanda’s exceptionally high population density contributed (McDoom Reference McDoom2020). Hatred was further aggravated by dynamics that unfolded in the process of killing itself: “Put simply, killing produced groups, and groups produced killings” (Fujii Reference Fujii2009, 186; related, for the Shoah, see Browning Reference Browning1998, 184).

A study of members of Arab tribes in Darfur who were not mobilized into the Janjawiid or other killing units might yield similar results. In the absence of involvement of non-organized forces in Darfur, however, we cannot answer with certainty the question whether this difference between research on Rwanda and results by Hagan and Rymond-Richmond (Reference Hagan and Rymond-Richmond2009) for Darfur is due to different research foci or due to distinct patterns of action. Yet the latter clearly seem to have played a role.

In short, scholarship on Rwanda confirms core elements of the Darfur model of genocide. Power and control, differential organization, social and collective efficacy, intensifying resource competition, and the hardening of ethnic boundaries all play out in both cases. Yet scholarship on the Rwandan genocide also displays distinctions. The role of ideology in establishing collective efficacy at lower levels of the power hierarchy appears to have been supplemented by local grievances and group dynamics and furthered by threat, coercion, and strategic consideration that often shaped the actions of the Rwandan perpetrators. Future scholarship may inform us if these distinctions result from the historical specificity of each situation or from methodological differences.

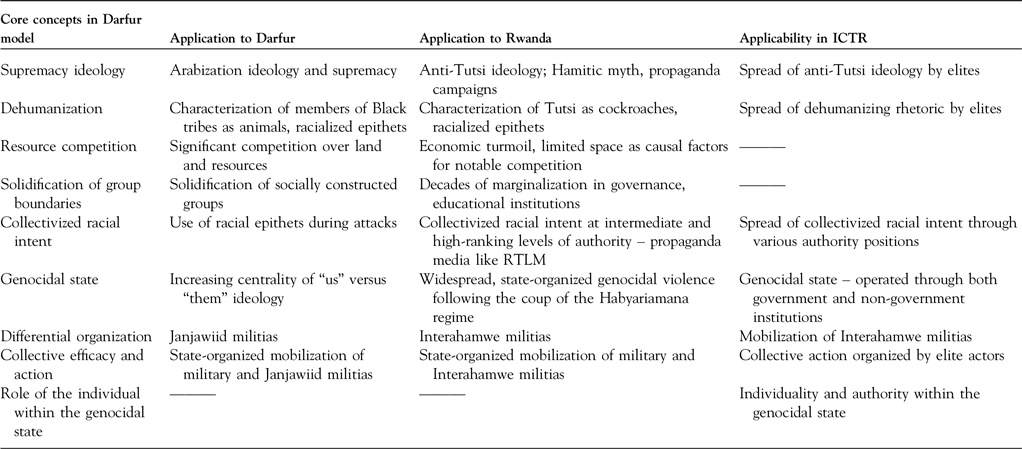

We capture these patterns in Table 1. Importantly, we do not intend for comparability between cases as depicted in the table to imply exact overlap—certain concepts manifested in both cases but in different ways. One example is the role of collective action. The state delegated tasks to militias in both Darfur and Rwanda, but these militias were distinct in terms of tactics and mobilization.

Table 1. Core categories in the social scientific model on Darfur, in scholarship on the Rwandan genocide and in the judicial narratives generated by the ICTR

The Crime of Genocide before the ICTR

While John Hagan (Reference Hagan2003) insists that social scientists cannot rely on judicial shortcuts when engaging with the collective processes that culminate in genocide, he is open to drawing on evidence, generated in the context of judicial interventions. In this spirit, we now simultaneously explore the particularity of judicial knowledge, in relation to its social science counterpart, and the potential of scientifically relevant insights from judicial proceeding. Specifically, we compare the judicial narrative produced by the ICTR with both the social science narrative on Rwanda and with Hagan and Rymond-Richmond’s (Reference Hagan and Rymond-Richmond2009) Darfur model (see column 4 in Table 1). A comparative analysis indeed displays dissonances between the Darfur model and the narrative generated by the ICTR, but it also reveals potential for insights, produced by the court, into the mechanisms that enable the power of authority and institutions in mobilizing genocide. ICTR narratives, importantly, are not just distinct as judicial accounts but also as they are generated by a court that divided its judicial labor with domestic Rwandan and local Gacaca courts. As the ICTR primarily addressed crimes committed by elites, it likely missed some of the intricacies of mobilization that Hagan and Rymond-Richmond identify at the micro- and meso-levels of their explanatory model.

We reconstructed the ICTR narrative by analyzing a sample of initial court judgments. We created a coding document based on the Darfur model to capture key information about individual defendants, including their bureaucratic role during the genocide, their various forms of formal and informal authority, and their defense. We then engaged with each charge in turn, capturing the types of mobilization, the scale of the crime, the types of violence, and the participants. We selected a broad array of cases to ensure that we were capturing patterns across roles, ages, and regions, focusing on discussions of individualized criminality over the court’s historical contextualization of the genocide. We examined forty-three cases until we reached saturation. We analyzed these documents for central patterns, charted below. With its focus on high-level authority, the ICTR narrative provides generative engagement with the highest levels in the genocidal regime of the Darfur model. We address these in turn through discussions of authority and institutions and the role of individuals in the genocidal state. While tracing valuable insights generated by the court, our analysis also shows the limitations of the court’s narrative, specifically regarding mobilization and the transformation of the orders into action that social scientific work has identified (for example, Straus Reference Straus2006; Fujii Reference Fujii2009; Luft Reference Luft2015; Kimonyo Reference Kimonyo2016).

Authority and Institutions

In 1994, the United Nations organized the ICTR to try those responsible for genocide and crimes against humanity in Rwanda as well as Rwandan citizens in neighboring states. While the language of the founding charter is broad, the ICTR targeted ninety-three actors, who were the organizers of genocide from a wide variety of state and non-state institutions.Footnote 3 They included government officials at the national and local levels, high-ranking military officers, members of the media, religious officials, and business leaders. The prosecution charged these actors with organizing and inciting violence at the lower levels of the genocidal hierarchy (Palmer Reference Palmer2015). Compared to earlier international criminal tribunals in the aftermath of mass violence and genocide, the ICTR applied a much wider conceptualization of culpability, with little regard for the notion of state sovereignty. It is thus more likely to capture elements of the social scientific Darfur model than, say, the IMT in Nuremberg.

Not only did the ICTR’s founding charter increase the court’s institutional breadth; the ICTR also made room for both formal and informal forms of power and authority in attributing culpability. In other words, the court did not limit its deliberation to actors holding formal bureaucratic roles, but it also considered informal social bonds in its deliberations. The case of Laurent Semanza provides an example. Semanza had been the Bourgmestre, or mayor, of the town of Bicumbi for more than twenty years. However, at the time of the genocide, he was no longer in a position of formal authority. Consequently, the defense argued that Semanza could not be held legally responsible. The ICTR, however, incorporated both Semanza’s formal and informal power into its deliberation: “The Indictment alleges that the Accused had de jure and/or de facto authority over militiamen, in particular Interahamwe, and other persons, including members of the Rwandan Armed Forces, commune police, and other government agents.”Footnote 4

While the court did not establish proof of genocidal intent, it charged Semanza with numerous crimes against humanity without holding a formal government role, illustrating the court’s recognition of numerous forms of authority in wielding the genocidal regime. The court thereby generated an image of Semanza as an actor with substantial social efficacy, in line with the weight attributed to social efficacy in the Darfur model of genocide (see also Matsueda Reference Matsueda2006). This focus is appropriate and reflective of social science insights—for example, Fujii’s (Reference Fujii2009, 186) conclusion that, “[i]n the presence of authority figures and other killers, group ties prevailed, pushing Joiners to go along with the group in its genocidal activities.” By accounting for both formal and informal sources of power, the ICTR’s narrative thus approximates a contemporary criminological understanding of the causes of mass violence more than preceding international courts did.

Individuals in State and Genocidal Bureaucracies

In establishing varied institutional arenas and varied forms of authority and power, the ICTR opens space for commentary on the relationship between individuals and institutions. Legal logic either necessitates individual accountability or hides collective mechanisms behind formulas such as “criminal organization” or “joint criminal enterprise.” These shortcuts contrast with criminological thought that spells out the specific social mechanisms at work in collective and institutional explanations of genocide. At the ICTR, institutions and collective processes were not on trial but, rather, the individuals who drove them. Nevertheless, our analysis of the ICTR’s deliberation of the relationship between individuals and institutions reflects, in line with Hagan and Rymond-Richmond (Reference Hagan and Rymond-Richmond2009), a non-linear understanding of the relationship between state institutions and involvement in the execution of genocide.

In the eyes of the ICTR, a position in the military hierarchy alone did not provide sufficient evidentiary proof. Instead, the court sought to prove that actors had wielded their authority for genocidal purposes. The court detailed this, for example, in the case of Anatole Nsengiyumva, a regional-level army commander:

The Chamber is satisfied that Nsengiyumva had actual knowledge that his subordinates were about to commit crimes or had in fact committed them. As discussed above, it is clear that these attacks were organised military operations requiring authorisation, planning and orders from the highest levels. It is inconceivable that Nsengiyumva would not be aware that his subordinates would be deployed for these purposes, in particular in the immediate aftermath of the death of President Habyarimana and the resumption of hostilities with the RPF when the vigilance of military authorities would have been at its height.Footnote 5

Here, the court specifically illustrates how Nsengiyumva wielded his state-sponsored authority with genocidal intent. This was not the case across all government actors, as exemplified in Prosecutor v. Bizimungu et al.Footnote 6 This case tried four political officials who held government positions both before and after the coup. The fact that these representatives occupied government positions within a genocidal regime was not enough to establish criminal culpability in genocide. This reflects the court’s understanding of a genocidal regime that closely overlapped with the state but did not mirror it. To occupy a role of authority in the genocidal state was not enough to prove legally that one was culpable of genocide. The ICTR investigated numerous members of the genocidal regime for crimes, but the court did not find them criminally responsible. In the Bizimungu et al. trial, two of the four government officials were found not guilty. The ICTR’s narrative decouples individual actors from the state itself. It insists that the genocidal regime is steered by actors, each with different levels of personal involvement in enabling or organizing violence.

The Rwandan case thus illustrates not only the court’s recognition of the state as a collective entity involved in the commission of the genocide but also the social dynamics within the state apparatus that resulted in varying degrees of responsibility among the state actors. A dialectic emerges in which the conversion of the state into a genocidal regime transforms authority relations within the state in several respects. It elevates the authority of some individuals—those who were more intimately engaged in genocidal goals—while potentially weakening or isolating the power of others. In the case of Rwanda, the immediate instability in the government structures caused by the assassination of President Habyarimana enhanced the power of more extreme actors to enact the genocide. In Omar McDoom’s (Reference McDoom2020) terms, it created an opportunity structure that was a necessary condition for the genocide to unfold. The ICTR recognizes these processes—its narrative thus again approximates that of the Darfur model, and its evidence contributes to a social scientific understanding of the Rwandan genocide.

Mobilization and the Transformation Problem

Despite the potential gain that the ICTR’s work can yield for social science explorations of genocide, the institutional set-up of the court and its rules do not allow the proceedings to capture several core elements of the Darfur model. While the court held actors legally accountable for their participation in incitement, the methods of incitement were not central to the court’s legal logic. Consider the case of Joseph Serugendo, a member of the RTLM governing board, who the court convicted of incitement. In discussing his role, the court concluded that he, along with others in positions of power,

[planned meetings and rallies] in order to indoctrinate, sensitize, and incite members of the Interahamwe to kill or cause serious bodily harm to members of the Tutsi population, with the aim of destroying the Tutsis ethnic group. … [He took part in] the establishment, funding and operation of the RTLM as a radio station to disseminate an anti-Tutsi message and to further ethnic hatred between Hutu and Tutsi … [and he admitted to going] to the RTLM studios between 6 April 1994 and 12 April 1994, accompanied by armed militias, to offer technical assistance and moral encouragement to ensure that RTLM broadcasting continued uninterrupted.Footnote 7

For the court, Serugendo’s occupation of bureaucratic roles and the fact that he operated within these roles to allow the broader genocidal state to function are legally relevant. At times, it matters how individuals have operated in their role (for example, through “moral encouragement”). Yet the efficacy of role performance—how the genocidal message was conveyed and the way in which it was understood—are not legally relevant. Rather, the legal logic dilutes the narrative to a cause and an effect, disregarding central elements of the Darfur model regarding mechanisms of mobilization. The case of Callixte Nzabonimana further illustrates this point. Nzabonimana, a government official in the genocidal regime, was also convicted of inciting genocide. However, in this case, the court’s narrative does not capture the specificity of the messaging and reception of this incitement:

Nzabonimana directly called for the destruction of the Tutsi ethnic group, as such, with the requisite intent, in public gatherings at Butare trading centre on or about 12 April 1994, at Cyayi centre on 14 April 1994 and at Murambi training centre on 18 April 1994. The Chamber therefore finds Nzabonimana guilty of committing direct and public incitement to commit genocide.Footnote 8

Again, these descriptions do not tell how orders function within genocidal systems. Instead, the individualizing logic of criminal law comes to bear and limits insights in social dynamics. For example, the nature of the crime of incitement is at odds with Hagan’s model—as an inchoate crime, causality is not an essential element in proving criminal liability. In theory, the law thus decouples calls for violence from any violence that results. However, as Richard Ashby Wilson (Reference Wilson2017) observes in Incitement on Trial, the ICTR controversially included causation in its analysis of genocidal intent and incitement, particularly in instances where evidence for intent was limited. In other words, the court would prove intent of genocidal incitement by showing that words, even if coded or potentially ambiguous to outsiders, were interpreted by perpetrators as calls to violence that directly influenced their participation. However, this analytical approach was critiqued as a stark departure from historical criminalization of calls for genocide.

Even in this hybrid, controversial form, the ICTR’s analysis of causality ceases at the effect rather than interrogating the mechanisms of mobilization that are central to Hagan (Reference Hagan2003). Mobilization in socially organized processes is beyond the scope of the ICTR. At times, the court would speak to the meaning of instructions, but such narratives focused on the intent of the messenger rather than on the reception of the mobilized. Again, in the Bizimungu et al. case, the court speaks to legal interpretation of coded language and euphemisms:

[That Tutsi] must be killed was made clear by Sindikubwabo’s calls to “work”, which in the context of the genocide was frequently interpreted as a call to “kill”. His statement that the war could be won if Butare “rid us of the irresponsible people” made clear that the passivity of Butare residents towards killing Tutsis could no longer be accepted, and that those who opposed such killings could be eliminated as well. That the underlying message to “kill Tutsis” could be directly and clearly understood is supported by the fact that Kinyarwanda is a dynamic language, where communication is at times indirect and may require context to extrapolate meaning. Sindikubwabo’s closing admonishments that people analyse closely the words spoken to them, when viewed in context, confirms the coded nature of his instructions.Footnote 9

Again, this passage shows the court’s attempt to establish the genocidal intent of Théodore Sindikubwabo’s words. The specific (and sociologically crucial) ways in which these words shaped action is not legally relevant in comparison to the simple fact that they did shape action. In Rwanda, different courts tried the mobilized and the mobilizers. Each court had its own institutional goals that influence its narrative and approach to understanding the crime of genocide—as such, the ensemble of types of court proceedings cannot be read as a coherent whole (Palmer Reference Palmer2015; Drumbl Reference Drumbl, van Sliedregt and Vasiliev2014). However, we still insist that such jurisdictional division of labor exacerbates the limitations of the ICTR’s potential to capture collective efficacy and the mechanisms of mobilization that are central to Hagan and Rymond-Richmond’s (Reference Hagan and Rymond-Richmond2009) model of genocide.

BRIEF CONCLUSIONS: READING THE DARFUR MODEL AGAINST SCHOLARSHIP ON RWANDA AND ICTR NARRATIVES

This article has addressed core themes in John Hagan’s contributions to a criminology of genocide. They include the development of a causal model of genocide in the context of Darfur, an insistence that social science analysis cannot be constrained by the shortcuts through which legal concepts seek to address collective processes, and his simultaneous recognition that social science can nevertheless draw insights from court proceedings. Clearly, scholarship on the Rwandan genocide confirms core elements of Hagan and Rymond-Richmond’s (Reference Hagan and Rymond-Richmond2009) Darfur model of genocide. Differential organization, social and collective efficacy, and the hardening of ethnic boundaries are crucial to an appropriate understanding of both cases. Yet literature on Rwanda also highlights distinctions. Most noteworthy, the role of ideological indoctrination at lower levels of the power hierarchy in Rwanda was supplemented by threat, coercion, or local grievances and group dynamics that often shaped the actions of the perpetrators. Future comparative research should explore if these distinctions result from the historical specificity of each genocide, executed only by specialized groups in Darfur versus by a broad segment of the population in Rwanda, or from methodological differences between Hagan and Rymond-Richmond’s (Reference Hagan and Rymond-Richmond2009) work (a survey of survivors in the refugee camps) and scholarship on Rwanda (interviews and ethnography in the places of killing).

Our analysis of the ICTR proceedings confirms another line of Hagan’s (2003) work in the context of the ICTY. It shows that courts proceedings can generate evidence that may be beneficial to social science explorations. Yet our analysis also highlights the limits of court narratives, their selectivity in depicting mechanisms of collective mobilization, and their tendency toward individualization. The case of Rwanda further raises the question of what version of history a court writes when separate legal institutions process the mobilized and the mobilizer. In short, John Hagan’s incorporation of genocide into the criminological agenda and of judicial responses to genocide into socio-legal scholarship are immensely important. Our analysis of the case of Rwanda, first, confirms core elements of the Darfur model developed by Hagan and Rymond-Richmond (Reference Hagan and Rymond-Richmond2009), despite some historical specifics. Second, it supports Hagan’s insistence that the social science cannot be constrained by legal shortcuts when it is concerned with collective processes. Third, in line with Hagan’s work on the former Yugoslavia and the ICTY, it shows that social scientists can nevertheless learn from court cases, despite the specific institutional logic of criminal law.