Article contents

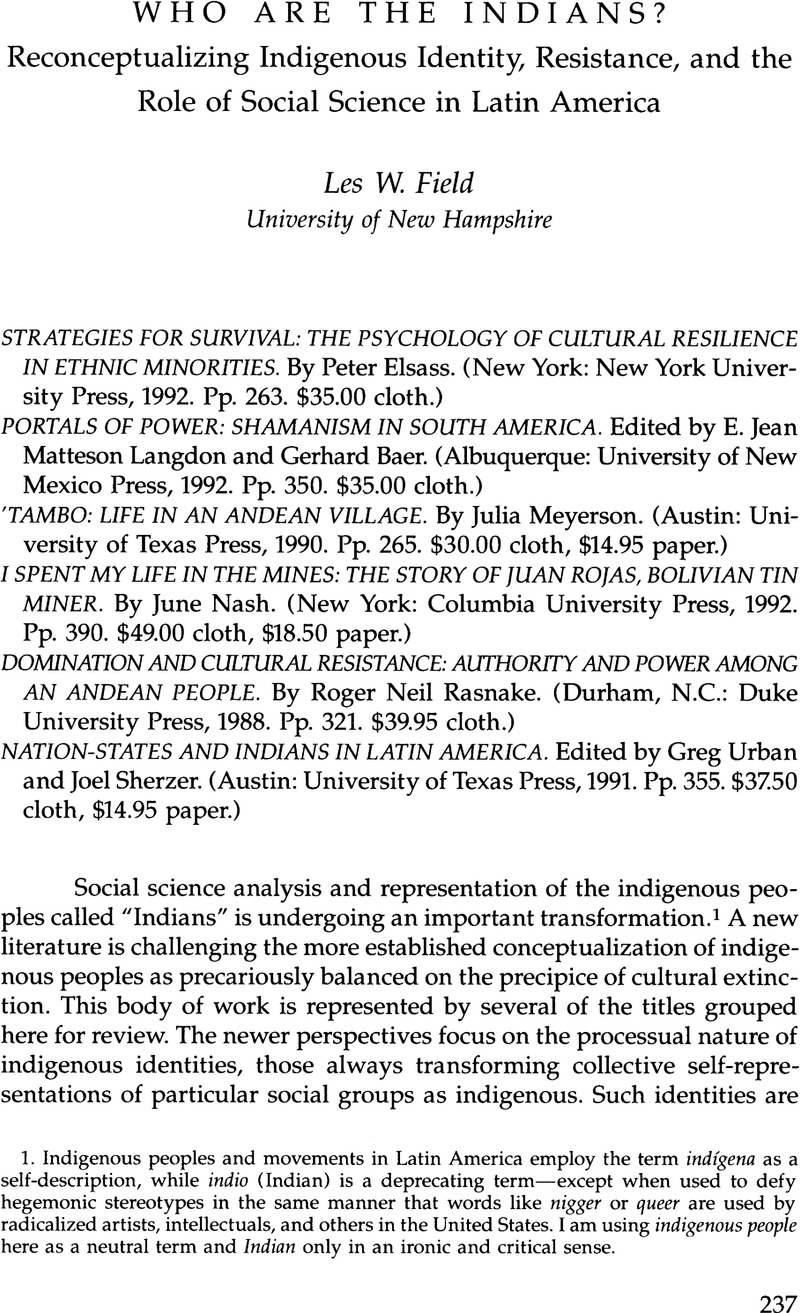

Who are the Indians? Reconceptualizing Indigenous Identity, Resistance, and the Role of Social Science in Latin America

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1994 by the University of Texas Press

References

Notes

1. Indigenous peoples and movements in Latin America employ the term indígena as a self-description, while indio (Indian) is a deprecating term—except when used to defy hegemonic stereotypes in the same manner that words like nigger or queer are used by radicalized artists, intellectuals, and others in the United States. I am using indigenous people here as a neutral term and Indian only in an ironic and critical sense.

2. In calling the established essentialist position the “cultural survival school,” I am in no way implying that this position represents the views of Cultural Survival International or its journal. Cultural Survival Quarterly has increasingly become a forum for authors, both academic and indigenous, who are writing from pronounced resistance perspectives.

3. See James Clifford, The Predicament of Culture (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1986). The postmodernist critique is turning out to be an ever-expanding industry. Two other important and insightful views are found in Johannes Fabian, Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object (New York: Columbia University Press, 1983); and George W. Stocking, Observers Observed: Essays in Ethnographic Fieldwork (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1985).

4. As social scientists encounter, analyze, and represent what they identify as essential-ism in the ideologies of indigenous political movements, they are being challenged to enlarge their discourses theoretically and politically while retaining their capacity for constructive critique. For a fascinating, intellectually honest encounter with Mayan nationalist ideology in Guatemala, see Kay B. Warren, “Transforming Memories and Histories: The Meaning of Ethnic Resurgence for Mayan Indians,” in Americas: New Interpretive Essays, edited by Alfred Stepan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992).

5. Urban and Sherzer accept Jean Jackson's view of ethnic groups (influenced by Fredrik Barth) as interest groups operating within larger societies, among whom markers of ethnicity are produced through interactions with other social sectors. This definition assumes the hegemonic domination of nation-states and their sovereignty over the territorial, collective, and individual rights of the ethnic groups embedded within each nation-state. Brackette Williams has greatly enriched this discussion through insightful considerations of the theoretical implications of class, race, and resistance in the construction of ethnicity. See Williams, “A Class Act: Anthropology and the Race to Nation across Ethnic Terrain,” Annual Review of Anthropology 18 (1989):401-55.

6. This point is stressed by Urban and Sherzer in the crucial distinction they make between highland and lowland peoples in South America: highland groups compose numerically large populations that have internalized European social and cultural forms since contact, while lowland peoples (in much smaller groups) remained more isolated and closer to precontact conditions for a long time. Urban and Sherzer also distinguish between the peoples living on the Pacific and Atlantic Coasts in Central America: the native societies of the Pacific Coast were incorporated early on into the Spanish empire and became part of the new Hispanic nation-states, while the Atlantic Coast peoples fell under the influence of the British empire and eluded incorporation into Hispanic nation-states until the twentieth century.

7. In several instances, anthropologists employed terms for indigenous groups for a long time that in no way corresponded to those people's self-identity and consciousness. It is interesting to note that the contemporary politics of resistance have created conditions under which indigenous peoples have adopted and adapted such terms. In the case of the “Mayans” of Guatemala, see Carol A. Smith, Guatemalan Indians and the State, 1540-1988 (Austin: University of Texas Press 1990). On the “Mixtecs” of Oaxaca, see Michael Kearney, “Mixtec Political Consciousness: From Passive to Active Resistance,” in Rural Revolt in Mexico and U.S. Intervention, edited by Daniel Nugent (La Jolla, Calif.: Center for U.S.Mexican Studies), 113-24. On the “Ohlones” of California, see Les W. Field, Alan Leventhal, Rosemary Cambra, and Dolores Sánchez, “A Contemporary Ohlone Tribal Revitalization Movement,” California History 71, no. 3 (Dec. 1992):412-31.

8. For the purposes of this essay, I am not discussing Elsass's African-American case studies, which form an important part of his argument.

9. Recent influential work has strongly legitimated indigenous systems that recount historical information, both as historical literature and as data that can be used to analyze and confirm the construction of indigenous traditions and identities. See Joanne Rappaport, The Politics of Memory (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990); Frank Salomon, Native Lords of Quito in the Age of the Incas (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986); and Rethinking History and Myth: South American Perspectives on the Past, edited by Jonathan Hill (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988).

10. Indigenism (indigenismo in Latin America) connotes a heavily romanticized idealization of the pre-Columbian civilizations of the Americas. Indigenismo in the past has characterized anti-hegemonic intellectual currents in Mexico, Nicaragua, the Andean countries, and Brazil. But it may have played a more significant role in serving as a means for political and economic elites to appropriate indigenous cultures for nation-building ideologies that end up maintaining the subaltern status of indigenous peoples.

11. Hill's analysis is developed in Kenneth Hill and Jane Hill, Speaking Mexicano: Dynamics of Syncretic Language in Central Mexico (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1986).

12. For the perspectives of the indigenous leadership on this process (among the Shuar and other indigenous Ecuadorian nationalities), see Confederación de Nacionalidades Indígenas del Ecuador (CONAIE), Las nacionalidades indígenas en el Ecuador (Quito: Ediciones Tincui Abya-Yala, 1989). Another recent consideration of the processes involved in constructing indigenous identity is found in Persistencia indígena en Nicaragua, edited by Germán Romero Vargas et al. (Managua: CIDCA-UCA, 1992). This work focuses on western Nicaragua, where twentieth-century elite ideologies have claimed the extinction of indigenous identity notwithstanding the persistence of self-identified communities.

13. Howe focuses in particular on one interloper, Social Darwinist Richard O. Marsh. During the 1920s, Marsh, in alliance with several notable anthropologists from the Smithsonian Institution, represented the Kuna as “a white tribe,” quite possibly the descendants of Vikings. According to Marsh et al., Kuna ancestors constructed the pre-Columbian architectural monuments found in Latin America.

14. See June Nash, We Eat the Mines and the Mines Eat Us (New York: Columbia University Press, 1979).

15. An insightful critique of the Andeanist literature that 'Tambo is part of and this literature's role in obscuring the conditions surrounding the revolutionary war in Peru is found in Orin Starn, “Missing the Revolution: Anthropologists and the War in Peru,” Cultural Anthropology 6, no. 1 (Feb. 1991):63-92

16. The politics of ethnography among the Miskitu forms the foundational subtext in Charles Hale, Resistance and Contradiction: Miskitu Indians and the Nicaraguan State, 1894-1987 (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, forthcoming.)

17. An outstanding and innovative example of the possibilities for such a reconfigured discourse is found in Zapotec Struggles: Histories, Politics, and Representations from Juchitán, Oaxaca, edited by Howard Campbell, Leigh Binford, Miguel Bartolomé, and Alicia Barabas (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institute Press, 1993).

- 39

- Cited by