Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 October 2022

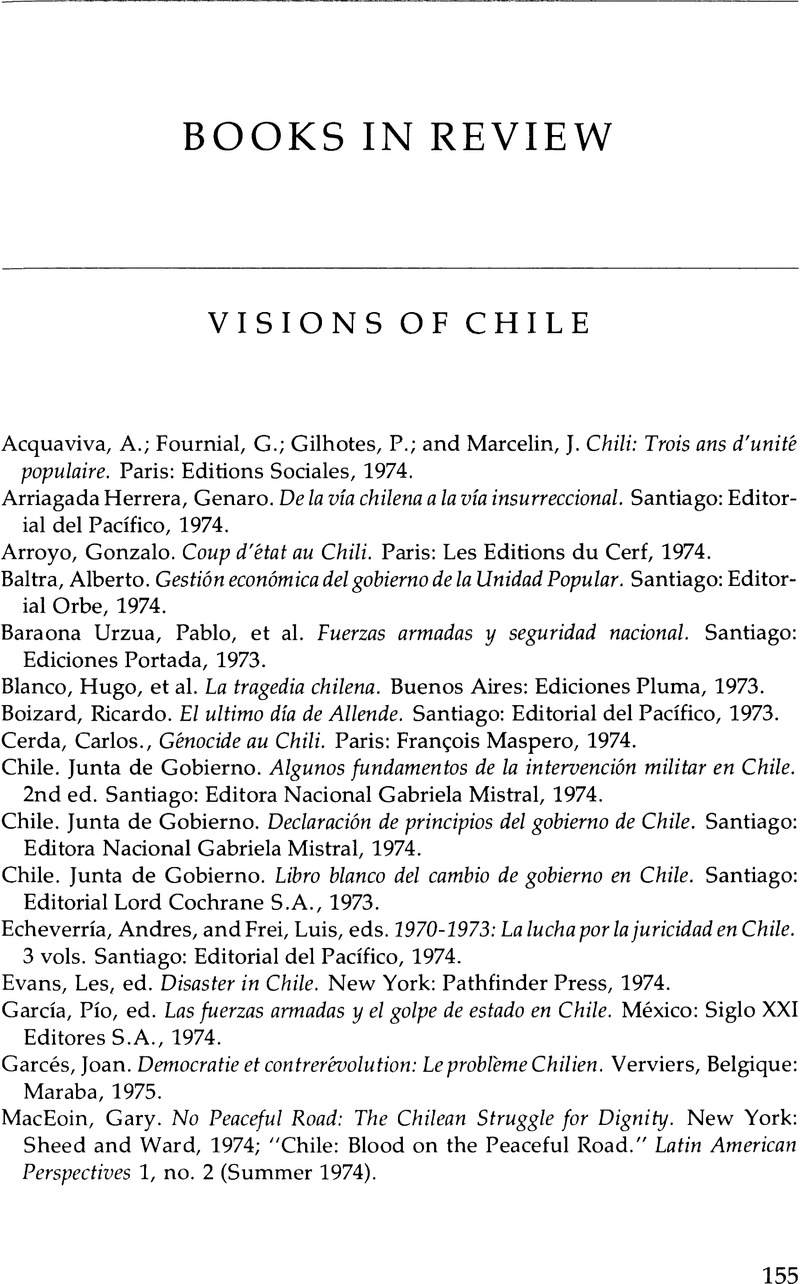

1. We include in this category Blanco, et al.; Evans; García; Mistral; Sweezy and Magdoff; and Toer. Some of the essays in the special issue of Latin American Perspectives should also be classified in this section. Several of these books consist of articles published during the Popular Unity period. Evans draws his articles from Intercontinental Press, Sweezy and Magdoff from Monthly Review, and García from Chile Hoy.

2. Mistral, p. 93.

3. Toer, pp. 22-23.

4. Mistral, p. 109.

5. Evans, pp. 12-15; Mistral, p. 116; Paul Sweezy, “Chile: The Question of Power,” in Sweezy and Magdoff, p. 19; Toer, p. 245; and Kyle Steenland, p. 10.

6. Mistral provides the most detailed analysis of the economic policies of the Popular Unity from this perspective. He notes that the economic strategy merely led to chaos because of the lack of political power. See Mistral, p. 66.

7. Sweezy, “Chile,” pp. 11-12.

8. “El golpe de la oligarquía y del imperialismo,” in Blanco, p. 22. Blanco and Evans present a Trotskyst perspective.

9. Sweezy, “Chile,” p. 11. The “myth” of a democratic transition is also noted by Betty and James Petras, “Ballots into Bullets: Epitaph for a Peaceful Revolution,” in Sweezy and Magdoff, pp. 156-60.

10. In his essay stressing the importance of external factors, Victor Wallis notes that the election of Allende was the result of growing anti-imperialism in Chile. See Wallis, pp. 44-57. Scholars who have analyzed survey data in Chile have questioned the view that the Allende election was the result of a significant change in the attitudes of the Chilean electorate. See James Prothro and Patricio Chaparro, “Public Opinion and the Movement of Chilean Government to the Left, 1952-72,” in Arturo Valenzuela and J. Samuel Valenzuela, eds., Chile: Politics and Society (New Brunswick: Transaction Books, 1975).

11. Paul Sweezy makes this point. See “Chile,” pp. 13-14.

12. Steenland, p. 11. He notes, as do other authors, that Popular Unity should have prepared for an armed confrontation in the early months of the government when it had the initiative. Though he notes that by 1973 the initiative was clearly lost, he implies that an armed solution would still have had a good chance of success.

13. Mistral, p. 113 and Toer, p. 110. Toer's book is the most impressive and valuable work in this category. It is a carefully documented source for declaration and policy statements of different political groups, primarily on the Left. Toer follows a chronological approach with relatively little interpretation in the text itself. The interpretation emerges from the many documents quoted often at great length. Unlike Mistral, its focus is primarily on political as opposed to economic questions. The analysis by foreign authors adds very little to the contributions of Mistral and Toer.

14. Toer, p. 176. See also Andrew Zimbalist and Barbara Stallings, “Showdown in Chile,” in Sweezy and Magdoff, pp. 125-26. In this article, written shortly before the coup, Zimbalist is more critical of the Popular Unity than in his earlier exchanges with Sweezy in the same volume. Nevertheless, he still implies that the failure was one of strategy and lack of decisiveness in following opportunities, than in the complete bankruptcy of the “Via Chilena” model.

15. See Toer, particularly pp. 211-15.

16. Toer, p. 245.

17. García, p. xlix. This book is a very valuable compilation of articles primarily on the armed forces and the relations between the government and the military. Drawn from Chile Hoy, they often reflect the good intelligence work of the MIR.

18. Les Evans, “Introduction,” in Evans, p. 14.

19. Initially spokesmen for MIR and MAPU called the military government fascist. See the declarations reprinted in Toer, pp. 301-13. Today, however, published and unpublished sources from the MIR stress the differences of the Chilean regime with the European fascists. They note in particular that the middle classes in Chile are not apt to be mobilized—and in fact are disenchanted with the economic policies aimed at benefitting only the large capitalists. Steenland makes a similar argument, p. 28.

20. Books in this category include A. Acquaviva, et al.; Arroyo; Garcés; MacEoin; Piacentini, et al.; Touraine; and Uribe.

21. Garcés, p. 9. Garcés was a top political advisor to Allende. He published several works during the Popular Unity government which are very useful to anyone interested in studying the period. This volume is a collection of previously published materials and does not provide an in-depth analysis of the Popular Unity years. However, Garcés will undoubtedly make major contributions in the future from the perspective of someone who does not think that the failure of a peaceful road to socialism is inevitable.

22. Touraine, p. 82. This book by a distinguished French sociologist and authority on the labor movement consists of daily commentaries written in Santiago between July and September 1973, supplemented by reflections written after the coup. This is one of the most insightful and interesting books to appear to date on Chilean events.

23. Arroyo, p. 36.

24. Touraine, p. 193.

25. Pablo Piacentini, “Crítica a la estrategia de la UP,” in Piacentini. See especially p. 57. See also Guillermo Medina, “La Democracia Cristiana y la crisis de Chile: La quiebra del centro político,” in the same volume, pp. 97-136.

26. Touraine, p. 192 and passim.

27. Piacentini, p. 68.

28. Touraine, p. 77.

29. See Acquaviva, et al., p. 177 and passim. These authors reflect the position of the Communist party and are thus very critical of the revolutionary Left. The book was hastily conceived and it has many basic errors of fact. Touraine is also critical of the Maximalists. See p. 91.

30. Arroyo, p. 36.

31. Touraine, p. 230.

32. Observers from this perspective are very critical of mistakes in economic policy. However, a good analysis of the economy during the Allende regime from their point of view is not yet available. The forthcoming book of Sergio Bitar, former minister of mines, will undoubtedly be a first rate work. On the unnecessary alienation of middle sectors through errors in economic policy see Garcés, pp. 208-14.

33. Nef, pp. 58-77.

34. Other authors give strong emphasis on the role of U.S. opposition to the regime. MacEoin, in a very journalistic and uncritical description of the Allende years, devotes substantial attention to the U.S.' involvement in Chilean affairs. See MacEoin, passim. Armando Uribe devotes his entire book to the efforts of the United States government to undermine the viability of the Allende experiment. Though somewhat overdrawn, this book presents fascinating material on the perceptions of Chilean policy-makers of United States policy and of the relations between the U.S. and the Chilean militaries. Uribe was a career foreign service officer who occupied several high positions during the Allende administration. See Uribe, passim.

35. Books in this category include Arriagada; Baltra; Echeverría and Frei; and Orrego. All were published after the coup.

36. Arriagada, p. 14.

37. Ibid., p. 23.

38. Ibid., p. 281.

39. Ibid., p. 130. A similar argument is presented in the introduction to the three volume work by Echeverría and Frei, p. 9. This work is an extremely valuable compilation of documents issued by opposing sides during the Popular Unity government. Primary attention is given to Christian Democratic declarations. The volumes include the text of the Statute of Guarantees, of the Christian Democratic sponsored amendment on areas of the economy and of the Chamber of Deputies on the “illegality” of the Allende regime. It includes the exchanges between Allende and the Supreme Court. Baltra also stresses that “from the government, Mr. Allende directed all of his acts towards the rupturing of the legality he had promised to uphold.” Baltra, p. 30. Baltra does not attempt to explain or document his assertion. Unlike Arriagada he does not suggest that this was a deliberate strategy stemming from a preconceived ideological posture, but implies that the Popular Unity simply became too power-hungry, unwilling to share its gains with the middle sectors. Baltra's small book contains information on the economic crisis of the Allende years.

40. Arriagada, p. 149. Arriagada interprets this as Allende's supporting the insurrectionary road, rather than his reappraisal of the “Via Chilena” because its “end” might have been misunderstood.

41. Ibid., p. 326. It is interesting to note that Allende's declaration to Debray—suggesting that his acceptance of the Statute of Guarantees (a condition for obtaining the necessary votes in the Congress to assume the presidency) was done for tactical reasons—is taken literally. But his many declarations supporting democracy and legality and criticizing the Left are underplayed as not reflecting his real intentions, or are refuted by quoting a contrary position from another member of the Popular Unity.

42. Ibid., p. 296.

43. Radomiro Tomic's forthcoming book on Chilean events will fill this important void. Tomic, the Christian Democratic candidate for the presidency in 1970, is one of the principal figures in the left sector of the party. Medina's piece in Piacentini, et al., comes closest to this position.

44. See Toer, p. 97, for precisely that interpretation of Allende's action.

45. Arriagada does not mention the military regime, nor do the volumes compiled by Echeverría and Frei.

46. Orrego, pp. 39-40.

47. Books in this category include the publications of the Junta de Gobierno; Baraona, et al.; Boizard; Millas and Filippi; Moss; and Silva.

48. Most of these publications argue that Allende lived a life of luxury. For a sampling of the worst see Boizard's chapter “Las mansiones y las orgías,” pp. 69-75.

49. For example see Boizard, p. 18; Millas and Filippi, p. 5; Junta de Gobierno, Fundamentos, p. 11.

50. The principal leaders of the Christian Democratic party, some of whom were involved in face to face negotiations with Allende, do not accept the view that the Plan Zeta was government policy. They note that many documents were produced by extremist political groups, so the documents themselves may be legitimate. But that Allende was involved in an “auto-golpe” is seen as ludicrous. This is based on interviews in Santiago during 1974.

51. Junta de Gobierno, Libro blanco, pp. 79-81. This book is available in an English translation as the White Paper on the Change of Government in Chile and has been distributed in the United States by the Chilean embassy. Citations are from the Spanish version. This is a surprisingly small number, given the political mobilization of the Allende years. Of this number, only twenty were clearly killed by members of the extreme Left. Others died of heart attacks when their land was taken, were killed by police or antigovernment forces, or died under unspecified conditions. These figures are in dramatic contrast with the number of deaths since the coup. Though some observers, such as Carlos Cerda, p. 27, exaggerate in suggesting that over 100,000 people died—the number is clearly several thousand. In almost every town and village in the country people were killed or disappeared. The government's policies of imprisonment and torture are well documented in books such as those by Cerda, Villegas, and White. The most substantial volume is that of Villegas. These books do not present reliable global figures on junta repression, but provide very valuable eye-witness accounts. They have been amply corroborated by fact-finding missions from Amnesty International, the Organization of American States, the International Labor Organization, and other special missions. The real scope of the junta's repression is yet to be fully documented.

52. Junta de Gobierno, Libro blanco, pp. 39-65.

53. Ibid., p. 95.

54. Ibid., p. 194.

55. Ibid., p. 114.

56. Ibid., p. 54. Even in face of this evidence, Silva persists in arguing that the president was fully behind the Plan Zeta—though he notes that he must have been unaware of its intention to assassinate him. Silva, p. 279.

57. Moss, p. 220. This book was originally published in English. See, Robert Moss, Chile's Marxist Experiment (London: David and Charles, 1973).

58. Hector Rieles, “La legitimidad de la Junta de Gobierno,” in Fundamentos, pp. 114-15. This article is reprinted from Baraona.

59. Rieles, “La legitimidad” in Fundamentos, p. 115.

60. Ibid.

61. Ibid., p. 126.

62. One of the most important accusations of illegality against the Allende government derived from opposing interpretations of the veto power of the president. Allende argued that a two-thirds majority was required to override a presidential veto on constitutional as well as ordinary legislation. The opposition argued that on constitutional legislation a simple majority was sufficient. Since the adoption of the controversial bill on the “areas of the economy” (which would have curbed executive power) was at stake, the juridical debate took on great importance. A reading of some of the literature on the constitutional reforms suggests that the president's position was a very strong one. See Eduardo Frei, et. al., Reforma constitucional 1970 (Santiago: Editorial Jurídica de Chile, 1970), and Guillermo Piedrabuena, La reforma constitucional (Santiago: Ediciones Encina Ltda., 1970).

63. It is fascinating to read the extensive declarations of the opposition elements of Congress, the courts, and other groups defending freedom and democracy during the Allende regime, with the knowledge that many of those same elements have been silent in the face of the clearly undemocratic practices of the current regime. As an example, see the declaration of the Chilean Bar Association (Colegio de Abogados) reprinted in Fundamentos, pp. 103-6. The evidence presented for the “illegality” of the Allende government pales when contrasted with the actions of the junta. And yet, when a prominent conservative lawyer urged the association to stand by its earlier principles, he was arrested for undermining the security of the state, and the Bar Association turned over his remarks to the military prosecutor.

64. Rieles, “La legitimidad” in Fundamentos, p. 128.

65. For an example of this reasoning see Ricardo Cox, “Defensa social interna,” in Baraona, et. al., pp. 73-121.

66. Silva, pp. 15-16. Moss does not go this far. He seems to view the military as basically democratic and intent on reestablishing democracy. But his view is challenged in the Spanish foreword of his book by Arturo Fontaine who notes that the Allende experience “broke the juridical mold of Chilean democracy and made it physically and morally impossible to restructure it in the same terms as before.” See Moss, p. 11.

67. Junta de Gobierno, Declaración de principios, p. 66. In subsequent speeches the junta members have continued to affirm that theme. For example, see Augusto Pinochet's speech of 11 September 1974, the first anniversary of the coup. He noted that the decay of Chile occurred with the “advent of partisan or demagogic governments, in which a small and sterile battle for particular benefits criminally divided the country and discredited all public men…. The political-partisan recess must be prolonged for years more, and can only be reestablished when a new generation of Chileans, formed in healthy patriotic and civic habits, and inspired by an authentic national sentiment, can assume the direction of public life.”