No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

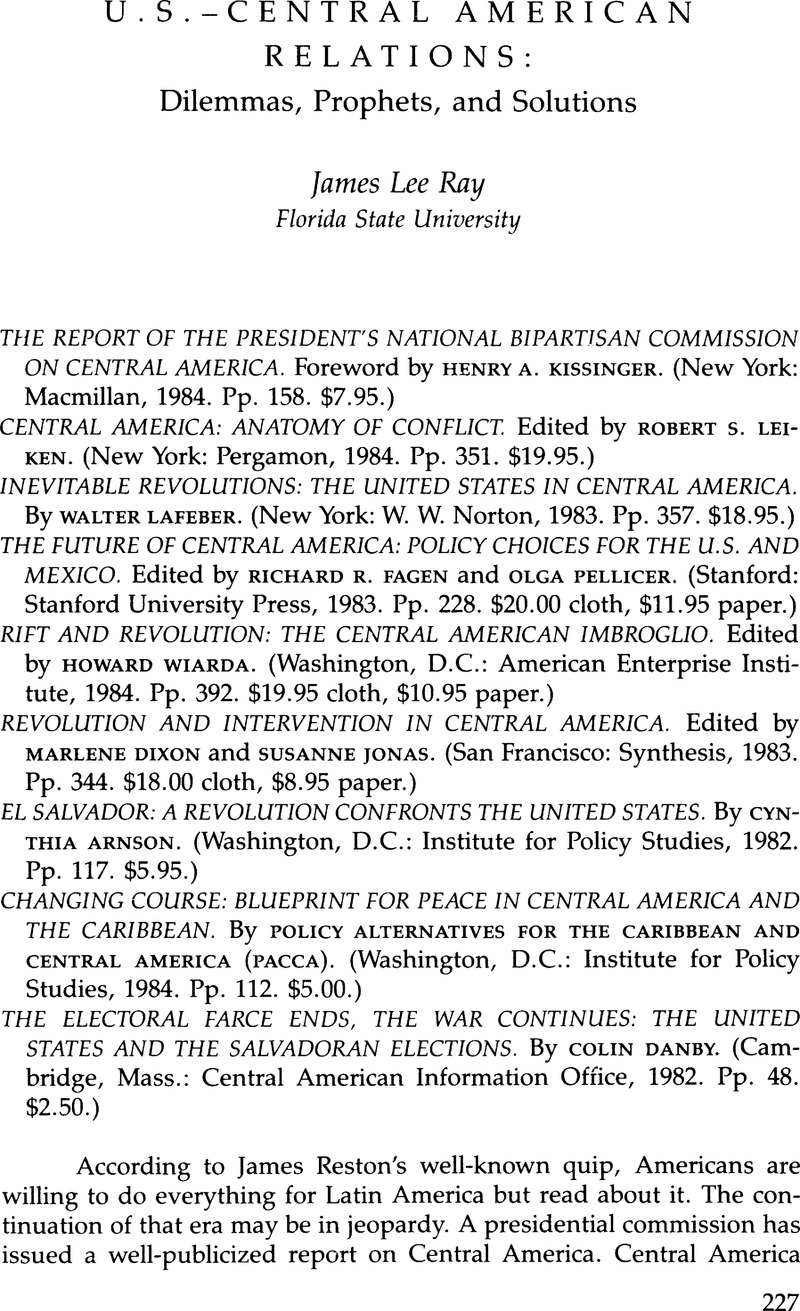

U.S.-CENTRAL AMERICAN RELATIONS : Dilemmas, Prophets, and Solutions

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1986 by the University of Texas Press

References

Notes

1. At another point, the Kissinger Commission report declares that “Cuba and Nicaragua did not invent the grievances that made insurrection possible in El Salvador and elsewhere. Those grievances are real and acute” (p. 103).

2. Cohen and Rosenthal provide a similar summary of the beneficial changes that occurred in Central America after World War II: “During the past three decades … real per capita income has doubled, and foreign trade has multiplied by sixteen; the countries are more urbanized, societies more differentiated, economies more diversified, and physical space better integrated” (p. 21).

3. William LeoGrande, a prominent critic of American policy in Central America and the Kissinger Commission report (as well as a contributor to The Future of Central America), criticizes the report because “the CIA's outster of Jacobo Arbenz in 1954—arguably the critical event in the failure of reformism not just in Guatemala but throughout the region—goes unmentioned.” See his article, “Through the Looking Glass: The Kissinger Report on Central America,” World Policy Journal (Spring 1984):4. But the commission report does in fact mention that “in Guatemala … the United States helped bring about the fall of the Arbenz government in 1954,” and even goes on to acknowledge that afterward “politics became more divisive, violent, and polarized than in neighboring states” (p. 25).

4. As evidence supporting this description of the worldview of an important sector of the Sandinista leadership, Cruz cites a speech given by Humberto Ortega to Sandinista army officers on 25 August 1981.

5. Jack Levy, “Misperceptions and the Causes of War,” World Politics 36 (Oct. 1983):81.

6. Richard E. Feinberg, “The Kissinger Commission Report: A Critique,” World Development (Aug. 1984):874.

7. Thomas P. Wright, American Support of Free Elections Abroad (Washington, D.C.: Public Affairs Press, 1964), 156-62.

8. Earl C. Ravenal, Never Again: Learning from America's Foreign Policy Failures (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1978), 70. Ravenal also quotes former Secretary of Defense James R. Schlesinger as saying that “one of the lessons of the Vietnamese conflict is that rather than simply countering your opponent's thrusts, it is necessary to go for the heart of the opponent's power: destroy his military forces rather than simply be involved endlessly in ancillary military operations” (p. 71).

9. See U. S. Grant Sharp, Strategy for Defeat: Vietnam in Retrospect (San Rafael, Calif.: Presidio Press, 1987), 269-70.

10. Ole Holsti and James N. Rosenau, “Vietnam, Consensus, and the Belief Systems of American Leaders,” World Politics 32 (Oct. 1979):5, 35, 38.

11. This “scenario” seems especially believable if, as Laurence Whitehead plausibly contends, the Reagan administration sees Central America primarily as an opportunity to refight the Vietnam War, this time to a successful conclusion. See “Explaining Washington's Central American Policies,” Journal of Latin American Studies 15 (Nov. 1983):360.

12. The phrase comes from Abraham Lowenthal, “The United States and Latin America: Ending the Hegemonic Presumption,” Foreign Affairs 55 (Oct. 1976):199-213. In a recent restatement of his earlier argument, Lowenthal asserts: “The fundamental flaw of U.S. policy toward Latin America in the past twenty years is not the failure to implement proposed new policies but the failure to deal with the overriding fact of contemporary inter-American relations: the redistribution of power. Since the early 1960s, U.S. policy has failed to cope with hegemony in decline.” See his “Change the Agenda,” Foreign Policy (Fall 1983):75.

13. “Vietnam and Central America,” a paper delivered by Jerome Slater at the annual meeting of the International Studies Association, Atlanta, Georgia, 27-31 March 1984, has played an important role in bringing me around to this point of view.