On November 16, 1951, the back cover of Topaze (Santiago, 1931–1970) displayed a striking political cartoon featuring Argentina’s president Juan Perón, standing and dressed in military outfit, surveilling a chess match between two candidates of the 1952 presidential election in Chile: on the left, a disproportionate horse-looking face representing Carlos Ibáñez, military dictator from 1927 to 1931, and on the right, Salvador Allende, iconic figure of Chile’s left-wing parties (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Unknown author, untitled, Topaze, no. 996, November 16, 1951. The text is as follows—Perón: “What a phenomenal horse! He knows how to play chess. Skillful horse, che Allende.” Chicho: “Not so much, Don Chumingo, because you are telling him how to move.”

The cartoon underscored the complex relationship between politics and the satirical press on the international stage. Both the exaggerated physical features of the protagonists and the fictional dialogue between Perón (“Don Chumingo”) and Allende (“Chicho”) suggested that Ibáñez was nothing but Perón’s puppet in Chile. Portrayed as an obedient horse (a nickname that he carried since his days as a talented horseman in Chile’s Military Academy), Ibáñez was constantly mocked by the press because of his sympathy toward Peronist Argentina. After years of exile in Buenos Aires and four unsuccessful attempts to return to power, including two electoral campaigns and two failed coups, Ibáñez won the presidency in 1952 with the support of a heterogeneous electorate that stretched from fascist clusters to disappointed leftists. In fact, Allende obtained only 5 percent of the votes, partly due to a division within socialist ranks over support for Ibáñez. While Ibáñez sought support in Argentina and conceived of Peronist policies as a model to replicate in Chile, Allende rejected Perón’s interference in domestic affairs. Topaze’s allegation that Perón controlled Ibáñez highlights the importance of Peronism and anti-Peronism in Chilean political culture. Although cultural depictions of chess for politics can be traced back to the Middle Ages, chess metaphors in Latin America’s satirical press became even more important during the Cold War, when the region became a crucial ideological battleground.

During the so-called Peronist decade (1945–1955), Latin American columnists debated Perón’s efforts to steer a course between the two Cold War superpowers by offering an intermediate position (“Third Position”) based on three ideas: social justice (justicialismo), political sovereignty, and economic independence. The three axes constituted the core of Peronism, which offered a political alternative in Argentina and across Latin America. Perón’s intentions, widely discussed in Chile, appeared early in intellectual circles and the popular press (Magnet Reference Magnet1953). Once elected president, Perón tried to erase the fascist overtones of the military dictatorship (1943–1946) from which he emerged, especially by empowering the working classes through higher wages, paid vacations, and labor reforms. Perón’s meteoric rise from an unknown colonel to a democratically elected president made him an international personality and attracted media attention across the Andes. However, his authoritarian credentials made most Chileans suspicious, especially because the governments of Juan Antonio Ríos (1942–1946) and Gabriel González Videla (1946–1952) comprised a center-left coalition of Marxist parties and middle-class reformists. This coalition resembled the parties that Perón persecuted in Argentina, particularly radicals, socialists, and communists (García Reference García2005; Artinian Reference Artinian2015). With the election of Ibáñez as president for a second term (1952–1958), Perón’s influence in Chilean politics reached its highest point. The antiparty style of Ibáñez, more than any clear-cut social coalition or reformist program, made him appear like a populist, as did his admiration for Peronist Argentina. Both leaders were mutual admirers and shared similar goals: reduce the influence of the party system, curtail the power of foreign capitalists in favor of state initiative, and act independently of the United States. Although both governments imposed official content in the press, their regimes were characterized by limiting dissent, enforcing several paper restrictions and temporarily closing opposition media, underlining the authoritarianism of their populist promises.

Peronist Argentina was often a source of inspiration and opportunity for Chilean cartoonists, who elaborated a set of “visual parodies,” that is, complex iconographic representations that imitate the manner, style, or characteristics of a particular societal norm or political ideology, with the intention of casting ridicule or inspiring laughter in the viewer (Sturken and Cartwright Reference Sturken and Cartwright2018). This article uses iconographic humor to understand “high politics” in line with the tradition inaugurated by Mikhail Bakhtin, for whom certain aspects of the world are accessible only through laughter (Averintsev et al. Reference Averintsev, Makhlin, Ryklin and Bubnova2000). As in the case of the French Revolution, images of Latin America’s early Cold War period were filled with tension and ambivalence, but they succeeded in opening up new fissures in the political terrain (Hunt Reference Hunt1984). The simplicity of images and exaggeration of Perón’s attributes became a useful mechanism to translate Peronism for Chilean observers. Cartoons were often produced to mobilize antipopulist sentiments, build identities, and intervene in the public discussion. Through their images, illustrators defined Peronist political culture in sharp opposition to Chile’s liberal democracy. They consciously sought to break with Peronist Argentina by representing Perón as a dangerous dictator and a setback from modernity. In the process, they created new cultural sensibilities and political divisions that surpassed the traditional left-right cleavage in a moment when other tensions emerged, such as the tension between Peronism and anti-Peronism. Visual parodies with Perón at the center also attempted to verify the democratic credentials of Chilean governments and their willingness to accept criticism without censorship or retaliation.

Histories of Peronism in Chile

The first academic studies on Peronism in Chile suggest that Perón failed in his proselytizing efforts across the Andes due to the strength of Marxist-based parties, and paradoxically, the most receptive Chilean elements were the nationalist groups (Bray Reference Bray1967). This line suggests that ibañismo was a vague doctrine, sharing three characteristics with Peronism: authoritarianism, nationalism, and hostility to the oligarchy. The concept of populism in Chile is generally associated with the Popular Front, a center-left coalition that echoed European multiparty experiences of the late 1930s, which became a Chilean moderate version of the Latin American populist experience due to the class alliances and reforms similar to those elaborated by Perón. In this view, Ibáñez’s populist trappings were rather weak, proving an ephemeral phenomenon that responded to the crisis of the governments led by the Radical Party since 1938 (Drake Reference Drake1978). More recently, several authors have recognized the populist overtones of Ibáñez not only as a demagogue campaigner but also as the personification of alternative democratization projects. Ibáñez’s populism was not a “populism” equally comparable to the experiences of Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico, where populist movements mobilized large masses along with accelerated industrialization and dynamic popular cultures. Ibáñez’s populism, rather, fed on the dissatisfactions produced by a system limited to a political elite but without significant economic and cultural transformations (Grugel Reference Grugel1992; Fernández-Abara Reference Fernández-Abara2007; Valdivia and Pinto Reference Valdivia and Pinto2018).

Further attempts to historicize geopolitical and economic relations between Argentina and Chile were reflected in studies on the Argentine-Chilean Economic Union Treaty and the diplomatic visits of 1953 (Vial Reference Vial, Fermandois and Luna1996; De Imaz Reference De Imaz, Fermandois and Luna1996). Although in recent years, historians of Chilean and Argentine diplomacy have offered innovative views on the study of Peronism in Chile, research still relies heavily on documentation from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and employs journalistic publications only marginally. Most of these academic works argue that, despite Peronist efforts to cultivate support in Chile (e.g., interference in plots, support in elections, a proposal for unified customs, and laudatory propaganda), local public opinion did not fall for Perón’s charm (Machinandiarena de Devoto Reference Machinandiarena de Devoto2005; Zanatta Reference Zanatta2013; Fermandois Reference Fermandois2015; Cortés Reference Cortés2016).

While acknowledging Ibáñez’s failure to establish a state project similar to Peronism but ascribing to the thesis of ibañismo as a movement with populist characteristics, a group of historians focuses on local Peronist sympathizers: first, ibañista women (who voted for the first time in the 1952 election), led by Senator María de la Cruz, an outspoken defender of Perón in Chile (Amaral Reference Amaral1994; Fernández-Navarro Reference Fernández-Navarro2002); second, nationalistic groups, whose antipluralism likened them to the most conservative segment of Peronism, that is, groups that aspired to an authoritarian government without reforms focused on the working classes (Fernández-Navarro Reference Fernández-Navarro2011); and third, Santiago populist tabloids such as Las Noticias Gráficas and Última Hora, whose editors were accused of receiving funds from the Argentine embassy to publish favorable news about Argentina (Acuña Reference Acuña2022). As for studies on Chilean anti-Peronism, El Siglo, the official organ of Chile’s Communist Party, stands out as one of the most antagonistic voices against Argentina’s political process initiated in 1943 (Fernández-Abara Reference Fernández-Abara2015). New research explores Chilean responses to Perón in mass culture. The sporting press, for instance, reacted favorably to the state initiatives promoted by Perón, most notably expressed in the organization of the Pan American Games in 1951. Despite celebrating the democratization of sports and its extension to women and children, Chilean sportswriters criticized Perón for his “excessive cultural diplomacy” and accused him of using sports with a proselytizing agenda (Elsey Reference Elsey2016; Acuña Reference Acuña2019).

Caricatures as transnational texts

The analysis of political cartoons illuminates important aspects related to the role of media in the representation of foreign state projects. Historians have read the importance of caricatures to contest European fascist powers in the interwar period (Navasky Reference Navasky2013), but little has been published about comical iconography in the context of intra–Latin American relations. Most works focus on nationally based visual cultures, such as Mexican muralism in the 1920s, which flooded the walls of public buildings (Folgarait Reference Folgarait1998), or the propaganda machine of Brazil’s Estado Novo (1937–1945), which crafted a positive image of President Getúlio Vargas as “the father of the poor” (Cardoso Reference Cardoso2021). Acknowledging these pivotal visual experiences, historians agree that Perón was effective in winning a portion of the media’s favor, and at the same time, he became infamous because of the extensive censorship of opposition media (Sirvén [1984] Reference Sirvén2011; Da Orden and Melón Reference Da Orden and Melón2007; Panella and Rein Reference Panella and Rein2008; Cane Reference Cane2012).

In the early years of Peronism, opposition media employed political humor. In Argentina, the magazine Cascabel denounced the Peronist regime as Nazi by insisting on Perón’s manipulation of the masses. Oscar Conti, who signed as “Oski,” often pictured Perón as the dictator “Juan Pueblo” and tied Peronism to brutality, ignorance, and contemptuous representations of the popular classes. Similarly, the socialist La Vanguardia, whose cartoons crafted by José Antonio Ginzo, better known as Tristán, depicted Perón as a Roman emperor and his supporters as headless brutes with swastikas (Panella and Fonticelli Reference Panella and Fonticelli2007). Facing competition against state-aid publications, both Cascabel and La Vanguardia lost readers, forcing their closure in 1947. The abundance of newsreels, magazines, schoolbooks, and cinema favorable to the regime made difficult to display satirical cartoons. Yet it would be precisely the excessive state propaganda that triggered an iconoclast fever aimed at eradicating every Peronist vestige from national life by the military that deposed Perón in 1955 (Plotkin Reference Plotkin2003; Gené Reference Gené2005).

While comparative frames help us to understand differences, they often reify the preeminence of the nation-state. Instead, visual studies of Latin American populism might benefit from transnational perspectives, illuminating the complex networks and information flows that produced Peronism and anti-Peronism beyond national borders. The use of biting visual parodies, montages, fake news, and satiric infotainment to question presidential authority became a strategy either to legitimize editorial positions or to score points against local competition. Peronism exceeded the Argentine nation and became a disruptive element in Chilean politics as a topic of daily discussion. Although it seems crucial to reiterate the importance of nationalism as an underlying element of anti-Peronism in Chile, political cartoons created narrative understandings of Perón that had broader meanings both locally and transnationally. Cartoonists played an important role in political contests as they criticized governments, denounced censorship, and forged transnational ideological affiliations (Alonso Reference Alonso2019; Sáez and Vera Reference Sáez and Vera2021). Chilean cartoonists, in particular, displayed extensive imagery on Perón as a classic Latin American strongman, depicting him as a narcissistic dictator and a malevolent giant able to sniff across the Andes to buy local adherents. Perón’s images illustrate Peter Burke’s (Reference Burke2001, 64) claim that nationalism is relatively easy to express in images, especially if they portray foreigners. The article focuses on nine cartoons featuring Perón to explore the ways Chilean cartoonists envisioned Peronism as an ideological caricature.

Topaze and the visibility of Perón

Topaze appeared in the context of the economic crisis of the old oligarchic order, when the irruption of the masses was seen as an opportunity to create more democratic media. Published between the fall of Carlos Ibáñez in 1931 and the rise of Salvador Allende in 1970, the magazine relied on humor as a mechanism for political debate, transforming itself into the most important satirical publication in Chilean history. Topaze’s popularity allowed it to print one hundred thousand weekly copies in its best time, an impressive figure for a country of five million inhabitants in the 1940s. The staff included writers such as Avelino Urzúa, Héctor Meléndez, Gabriel Sanhueza, Augusto Olivares, and cartoonists Jorge Délano (known as “Coke”), Mario Torrealba (“Pekén”), René Ríos (“Pepo”), Luis Goyenechea (“Lugoze”), and Luis Sepúlveda (“Alhué”). While readers had to be familiar with national and international events, Topaze had the ability to convey complex messages in a simple way. One of the main characters was Professor Topaze, a teacher with glasses, which represent intelligence and rationality. Another important character was Verdejo, the personification of the working classes: skinny, with poor clothing and imperfect teeth, but good judgment (Rueda Reference Rueda2011). Although Topaze’s readership was mainly middle class, cartoonists showed the ridiculousness of middle-class Chileans and their self-portraits as elites (Cornejo Reference Cornejo2007). Despite literacy campaigns that resulted in substantial improvements, about one-fifth of the total population still did not have even rudimentary literacy skills in 1952. Topaze employed eye-catching titles and colorful cartoons to reach those semiliterate and illiterate audiences. Yet most Chileans were not able to regularly buy magazines, so what appeared on the cover or what kiosks displayed publicly in the streets was important.

Topaze’s editorial line was in a position of criticism toward political power. Cartoons expressed nationalism and strong attachment to the institutional order. As bearers of an enlightened and rational mindset, the editors fostered freedom of speech, rejected militaristic violence, and criticized dictatorship. With a strong focus on global conflicts along with national problems, the magazine mocked local and world leaders, from both the Left and the Right, articulating an apparent “political neutrality” (Montealegre Reference Montealegre2008; Buttes Reference Buttes2017). Editors gradually turned to the right as they expressed anticommunist and pro-American commitments after World War II and most decidedly in the 1960s. Although there was not ideological unity within Topaze, there were anticommunists such as Délano and prominent left-wing journalists like Olivares, who was with Allende during the coup on September 11, 1973 (Salinas et al. Reference Salinas, Rueda, Cornejo and Silva2011).

Caricatures did not go unnoticed by authorities. Several incidents marked the beginnings of Topaze with censorship attempts in the 1930s, including one 100-day and two 180-day imposed silences. In 1937, the police burned all copies of the 285th edition because of a caricature that portrayed president Arturo Alessandri (1932–1938) as a lion tamed by Ibáñez. The incident ended up in court as the government ordered Délano’s arrest. However, justice ruled in favor of the magazine because the cartoon was not intended to alter public order (Donoso Reference Donoso1950; Hasson Reference Hasson2017). Topaze’s visual language challenged politicians, exaggerating their bodies to provoke ridicule and laughter. Humor was intended to reveal weaknesses and exaggerate ugliness, hence the importance of the disproportionate relation between heads, bodies, and text (Bordería, Martínez, and Gómez Reference Bordería, Martínez and Gómez2015).

By examining the frequency of covers in Topaze, this article identifies patterns that became central to the magazine’s critique of Peronism, expanding on some recent findings related to Perón’s presence in Topaze (Lacoste and Garay Reference Lacoste and Garay2022). Frequency analysis, which is quantitative in nature, can contribute to visual analysis by exploring how specific images shifted over time. Although comical representations of Perón in Topaze are most easily traceable during his presidency between 1946 and 1955, the study also contemplates depictions of Perón during the military dictatorship that preceded him and in the aftermath of his overthrow. With Perón deposed and exiled, Topaze continued to criticize Ibáñez and his government for their concomitance with Peronist Argentina at least until 1958, when new elections were held in Argentina and Chile. Topaze experienced numerous administrative changes the same year, provoking financial instability and a sales shortage. From 1943 to 1958, Perón figured on fifty covers (front and back) in 824 issues of Topaze, counting more apparitions than Salvador Allende (19) and outnumbered only by former and incumbent Chilean presidents such as Arturo Alessandri (87), Juan Antonio Ríos (111), Gabriel González Videla (274), and Carlos Ibáñez (342) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Chilean political figures and Perón on the covers of Topaze (1943–1958).

Just as each Chilean president is displaced by the next within Topaze, Perón remains in the imaginary of cartoonists fairly stable with a notorious peak after the election of Ibáñez: sixteen covers in 1953 (when Perón visited Chile) and nine covers in 1955 (when Perón was deposed)—a significant amount considering Topaze published an average of fifty issues per year. Although Topaze gave Perón visual attention only comparable to a Chilean president, not all mentions and visual parodies of Perón were the same or had the same interpretative value. More than any other non-Chilean political figure of the era, Perón became a frequent target of the magazine jokes, directly or indirectly (Figures 3 and 4). While direct mentions (DMs) refer to all the images and texts in which Perón is the explicit protagonist, indirect mentions (IMs) refer to all the images and texts in which Perón is absent but somehow tied to the joke. As Figure 3 shows, the number of DMs shows a strong predominance of images over written text, and that rises over two years, with a total of fifty-two cartoons in 1953 and thirty-eight in 1955. All the written mentions in 1953, whether direct or indirect, maintained a stable statistical behavior (seventeen DMs and sixteen IMs). Yet Topaze favored explicit visual content over indirect text because the jokes that alluded to Perón required a complex understanding and greater familiarity with Argentina’s political context.

Figure 3. Direct mentions (DMs) of Perón in Topaze (1943–1958).

Figure 4. Indirect mentions (IMs) of Perón in Topaze (1943–1958).

As Figure 4 shows, IM cartoons peaked in 1955, possibly because cartoonists were busier pointing the finger at local adherents than at Perón himself. When Perón was overthrown, the magazine increased written IMs in editorial pieces and poems, mainly to point out supporters in Chile. All mentions drop abruptly in 1958, when the attention shifts away from Perón and Ibáñez toward the presidential candidates.

While quantitative analysis provides numerical data, it does not take into account a deeper understanding of a satirical magazine. Political cartoons are not neutral or objective records of the past and require a complex examination. Taken together, satirical cartoons offer a panoramic view of a series of “microintentions” rather than a reflection of a universalizing ideology (Poole Reference Poole1997). Each cartoonist used satire to criticize and comment on particular issues and events related to the diplomatic climate between Chile and Argentina. Most importantly, they made people think about local and international politics, emphasizing animosity toward authoritarian regimes in Latin America. In other words, satirical images provided a symbolic and imaginary framework for Chile’s anti-Peronist political culture of the 1940s and 1950s.

Problem child, athlete, and seductive military man

The repercussions of Peronism in Chile began before Perón was elected president of Argentina. The news of the 1943 military coup caught the attention of Chilean media. With a rising career in the Argentine dictatorship (1943–1946), Perón became secretary of labor and social security and soon vice president and minister of war while cultivating an important support network among Argentine workers. Topaze described him as an opportunistic leader who seized power with a group of unprepared soldiers. An editorial published on July 7, 1944, suggested: “Perón makes a mistake by an abundance of energy, by an itch of action mixed with spectacularism. May he learn from other powerful dictators of our Americas, who wear civilian jackets and who, although they develop overwhelming power, are more prudent, more diplomatic, more skillful in their attitudes.”Footnote 1 Alluding to this lack of preparation and sense of hastiness, one of the first cartoons of Perón placed him in the middle of a baby fight with a group of quintuplets that represented the five generals in command, from left to right: Arturo Rawson, Pedro Ramírez, Juan Perón, Edelmiro Farrell, and Tomás Duco (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Jorge Délano (“Coke”), “The Leading Argentine Quintuplets: Sons of Mr. Nazism and Mrs. Revolution,” Topaze, no. 604, March 24, 1944.

The image was signed by Délano (“Coke”) on the bottom right and represented Argentina’s chaotic dictatorship and the internal disputes among the five generals. The disagreements alluded to the country’s prolonged neutrality during World War II, a conflict in which Argentina and Chile united with the Allies only in 1945. As their distaste for the United States, the sympathies toward the Axis countries by regime members were not hidden. Délano captioned the image as “Sons of Mr. Nazism and Mrs. Revolution” to make a point about the fascist nature of the new regime. Indeed, most Topaze cartoons about Argentina portrayed the 1943 revolution as a fascist experiment linked to the ultranationalist regimes in Spain, Italy, and Germany. Perón’s movement emerged when international fascism was not yet defeated and liberal capitalism was still damaged by global depression. In this particular cartoon, Délano focused on the quarrels of the Argentine generals, who succeeded one another in power. Almost intuitively, the cartoon mirrored the two factions that emerged after Rawson’s resignation. The first was led by Ramírez, who questioned Perón’s labor policy and wartime neutrality, pushing in favor of the Allies. The second was led by Farrell and Perón, who wanted to continue the successful alliance with the unions, leading a form of popular nationalism without compromising with any belligerent nation. Almost prophetically, the cartoon projected Perón as the winner of this quarrel as he slapped Ramírez in the face. Délano quickly detected the growing popularity of Perón, which responded to the progressive labor reforms that ultimately gave him a mass following.

Perón’s leadership was viewed suspiciously from Chile. Infantilizing the military leaders with huge bonnets and Perón carefully drawn at the center as problem child, Délano portrayed Argentina as a country controlled by possessive and spoiled babies. Only Perón and Farrell have pacifiers around their neck. Although the image represented democratic immaturity and childish rebelliousness, its visual message was not only about Argentina. Topaze sought to reaffirm the naive conviction that Chilean political institutions, unlike those in Argentina, were sufficiently mature and safe from military uprisings. Délano understood early that Perón was a dangerous leader who could inspire similar military movements in Chile.

Cartoonists conceived of the rise of Peronism in Argentina as a relevant phenomenon of geopolitical interest in the new Cold War scenario. Topaze frequently represented the international confrontation, understanding that the tension between the United States and the Soviet Union would have strong repercussions in Latin America. Although Perón attempted to erase the fascist undertones of the regime, he did not abandon the anti-US rhetoric used by his former military comrades. Using clever sports metaphors, Topaze represented Perón’s tactical victories over the United States. One back cover illustrated this ingeniously on August 18, 1944, when Topaze featured Perón celebrating his boxing victory over Uncle Sam, dedicating his triumph to an old lady in a bubble representing Hitler (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Unknown author, “International Match,” Topaze, no. 625, August 18, 1944. The text is as follows—Perón: “And I send greetings to my ‘old lady,’ who for sure is hearing me.”

Portraying Perón shirtless and wearing boxing gloves, boots, shorts, and a military cap, and bragging about his muscles and smile, was in contrast to the old and fatigued representation of Uncle Sam. Sports became a recurrent metaphor for Perón’s political actions. This was not a coincidence: Perón identified as “the First Sportsman of the Nation.” His administration actively promoted sports as a means of fostering class cooperation. He was a fencing champion in his youth and a regular attendee at soccer matches (Rein Reference Rein1998). In the boxing cartoon, the people in the background expressed the presence of a mass movement celebrating Argentina’s sovereignty against foreign intromission. Capitalizing on support, Perón emerged as a leader able to gather the support of the masses while repelling US imperialist policy. Sports images symbolized Perón’s success against smear campaigns, especially when the United States renewed propaganda campaigns against Perón. In February 1946, the US ambassador Spruille Braden insisted on disparaging Perón as pro-Nazi in his Blue Book, a publication that documented Argentina’s wartime relations with the Axis powers. Braden intended to discredit Perón before the election. Perón denounced Braden’s strategy and coined the slogan “Braden or Perón” for his electoral bid.

Uncle Sam represented a repeated image of US intromission in Latin American politics, albeit one contained by the strength of Perón. While this image expressed a degree of enthusiasm toward Perón, it also warned Chilean readers about his personality. The presence of Hitler became a common feature as the magazine tried to simplify Peronism by equating it with the rise of fascism in Europe. If the United States was fighting Nazi Germany in Europe, it should have been also confronting Perón in Latin America. But unlike the European front, the United States was losing ground to a charismatic Argentine colonel. Perón had dedicated himself to a dramatic revision of Argentina’s social hierarchies and a program of state-driven economic growth, both of which stood in stark contrast to the capitalist order favored by US policy makers. Furthermore, Perón did not confine his vision to Argentina but worked diligently to export his populist brand to the other nations. This belief, according to which Argentina would achieve a hegemonic position on the continent, became one of the underlying forces that nurtured Peronist diplomacy in the 1940s. Somehow, this image contains the idea that Perón could handle US imperialists and force them out of Latin America.

In Chile, the influence of the United States also became a problem for the center-left alliance that had sustained González’s administration. His government was facing high inflation rates and labor unrest. Aware of the situation in Chile, Perón offered a trade agreement of raw materials that would underpin Argentine industries while securing a much-needed food supply for Chile. However, the negotiations were seen suspiciously by US diplomats. Topaze saw Perón’s intentions as an attempt to curtail the influence of US diplomats in Chile. On the front cover of January 4, 1947, Topaze featured Perón and González dancing tango in front of a jealous Uncle Sam (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Jorge Délano (“Coke”), untitled, Topaze, no. 746, January 4, 1947. The text is as follows—Uncle Sam: “So, darling, do you prefer tango now?” Perón: “Yes … We already began, old man, with ‘Tomo y obligo.’”

Topaze’s cover portrayed Perón as a seductive military man next to a feminized and dark-skinned González. Délano’s cartoon exaggerated González’s smile and distinctively pictured him as nonwhite in contrast to Perón and Uncle Sam. Although many politicians were dressed in women’s clothes to comic effect, the cartoon feminized González to undermine his authority and integrity. This form of satire was often used during times of political unrest. In addition, González and Perón appear slightly inclined and rubbing their bodies, denoting closeness but distance toward Uncle Sam. The mention of Carlos Gardel’s 1931 tango song “Tomo y obligo” provided a popular reference to understand Cold War diplomacy: the lyrics refer to a weakened old man betrayed by his wife. Délano employs ridiculousness as a narrative device to criticize González for his temptation with the younger soldier, undermining Uncle Sam, who tries to wield authority in broken Spanish: “ahora preferir bailando tango.” Indeed, the presence of Uncle Sam reinforced the idea that Perón was able to seduce González regardless of imperialist pressure. Uncle Sam’s defiant look and finger indicating “Chile’s betrayal” are an effective gesture for the viewer, especially considering that González ultimately refused an agreement with Perón and outlawed his former communist allies through the Law for the Defense of Democracy in 1948. Although initially leaning toward Perón for the meat and wheat offered in exchange for copper and coal, González finally chose to further an alliance with the United States, increasing Chile’s dependence on loans on the condition of repressing left-wing mobilization. Radicals and socialists (the other parties in González’s coalition) were aware that Argentine resources were vital, but not at the price of falling within the Peronist orbit. Perón did not see the repression of left-wing activists as a way to collaborate with the United States; rather, it became another front to challenge US presence in the region. In that sense, the cartoon showing Perón seducing González emphasized that the two Cold War actors fighting over Chile’s resources were the United States and Argentina (not the Soviet Union).

Ibáñez, print media, and Peronist followers

After the setbacks with González, Perón pushed for direct intervention in October 1948, when a group of Chilean military officials conspired in a failed coup discovered on time. The pig trotters’ plot (as it became known because the plotters gathered in a restaurant that specialized in the typical Chilean dish) was the riskiest maneuver of Peronist interference. The report that warned against the plot came directly from the United States and indicated that the Argentine embassy was funding an uprising to install Ibáñez as dictator. After the episode, Ibáñez reappeared on the covers of Topaze, usually portrayed as an instigator of conspiracies to return to power. When Ibáñez announced his candidacy for the 1952 elections, the magazine dedicated several jokes to denounce Argentina’s involvement in the campaign. On October 5, 1951, editors commented, “Although Argentina provides us with meat, potatoes, oil, and other essential items, by no means Argentina must also supply us with presidents.”Footnote 2 Topaze maintained mistrust toward the Argentine government, insisting that Perón was a threat to Chilean democracy.

Most of the Chilean press was on alert or decidedly against Perón was due to his authoritarian stance against journalistic independence in Argentina, especially after the confiscation of the conservative daily La Prensa in March 1951. In light of reduced press liberties in Argentina, Topaze cartoonists commonly drew Perón as a military man and rarely as a civilian who crushed the opposition media. On March 23, 1951, Topaze featured Ibáñez and Perón having a conversation about newspapers in Buenos Aires (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Unknown author, untitled, Topaze, no. 963, March 23, 1951. The text is as follows—Perón: “Che, horse, why are you coming again? Is it for the payments?” Ibáñez: “I’m looking for a newspaper for my presidential campaign.” Perón: “And what are friends for, man? Just take La Prensa away.”

In the fictional dialogue near the obelisk (to indicate that the conversation was in Buenos Aires), a smiling Perón asks Ibáñez if he wants money. Ibáñez responds that he needs a newspaper to advocate for his campaign, to which Perón suggests taking La Prensa away with him. Carefully drawing Ibáñez wearing a suit (as opposed to a military uniform), Topaze warned readers about the risks of electing authoritarian rulers, especially those who pass as democratic leaders. Cleverly placing Perón as the protagonist, the cartoon offered a subtle but no-less-scathing critique to Ibáñez’s tactics against the press. Chilean journalists frequently pointed out his tense relationship with the press during his first administration, particularly when he confiscated the daily La Nación in 1927, placing it under government control. Once back in power, Ibáñez lashed out at the media for “manipulating the news,” accusing journalists of spreading misinformation about his government (Correa Reference Correa1962). Explaining his vision of press freedom in the opening speech of the World Congress of Journalists, held in Santiago in 1952, Ibáñez declared: “No one knows better than you that press freedom tends to become an information monopoly of governments or economic groups that subordinate the interest of the people and the community to their own interests” (Valdebenito Reference Valdebenito1956, 116). Ibáñez criticized the concentration of media in a few hands, distancing himself from Perón’s vertical control over the press in Argentina, where the state assumed a preponderant role in defining media policy. However, in practice, Ibáñez made regular use of the Law for the Defense of Democracy, arresting journalists and closing down newspapers (Acuña Reference Acuña2022).

Topaze located Ibáñez as an anomaly of the established system who arose from outside the traditional channels of power; it described his ascent similarly to the rise of Perón in Argentina. Editors commented on Ibáñez’s popularity: “The masses, guided more by instinct than by any rational assessment of doctrines or values, cried out to Ibáñez, as one would cry out to a policeman when in danger of being attacked.”Footnote 3 His electoral victory was seen as the result of social fears and not the product of a coherent historical process. The “General of Victory” attracted a groundswell from the discontented middle and working classes, as well as a few socialists attracted by Peronist Argentina and hoped to use Ibáñez’s appeal to recapture the masses for the Left. Always a mercurially pragmatic man and not charismatic, Ibáñez was nothing like Perón. The magazine constantly addressed his evasive personality and ideological zigzags, labeling his administration as a government with no fixed program, neither of Right nor Left, neither democratic nor revolutionary, insipid and ambivalent—a rarity in the Chilean political system.

With Ibáñez in power, Perón launched proselytizing efforts that included funds to local newspapers and radio stations as well as invitations extended to army officers, labor leaders, and journalists to Buenos Aires. Chile had its own group of staunch Peronist followers that received media attention during Perón’s visit to Chile in February 1953. The visit occurred just a week before parliamentary elections, triggering accusations that Ibáñez wanted to influence the vote. Although Ibáñez failed to win a majority in Congress, several Chilean Peronists rose to positions of power. One of them was María de la Cruz, Chile’s first female senator and leader of the Chilean Women’s Party, which played a significant role in Ibáñez’s victory, considering that women voted in presidential elections for the first time in 1952. De la Cruz capitalized on national disillusionment and promised to defend Chilean families from the “moral chaos” caused by political parties. She gained recognition not only for her association with Ibáñez but also for his friendship with Perón, a relationship that aroused many jokes in Topaze (Figure 9).

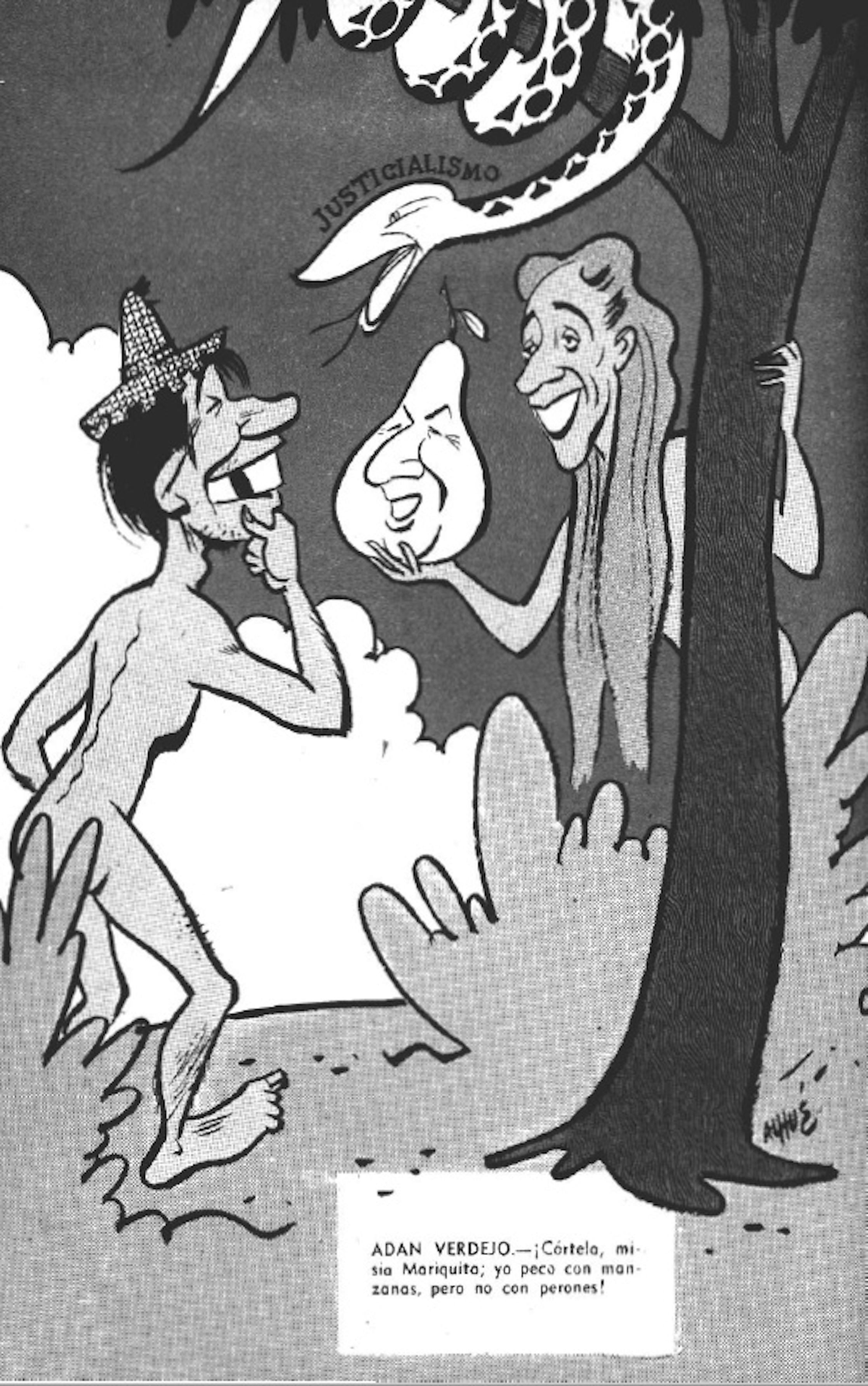

Figure 9. Luis Sepúlveda (“Alhué”), untitled, Topaze, no. 1064, March 6, 1953. The text is as follows—Adán Verdejo: “Stop it, my aunt Mariquita; I sin with apples, not pears!”

Cartoonists such as Luis Sepúlveda (“Alhué”) used mythical imagery to creatively illustrate the political situation. Adapting the mythical story of the Edenic tree of knowledge, Sepúlveda satirized Senator de la Cruz as the biblical Eve, tempted by a forbidden fruit—in this case, a Perón-like pear, or pera in Spanish, a word that sounds like Perón. Descending through the branches, the snake figuratively represented Peronism (or justicialismo) in front of a naked Juan Verdejo, who personified the “common people.” Embodying Adam, Verdejo assessed that he was willing to sin only with apples, not pears (or perones). In addition, Verdejo appeared with his index finger on his chin, a traditional sign of doubt and skepticism. By feminizing the threat of Peronism and placing it as a temptation, Topaze’s illustrators responded to the popularity of Perón after he visited Chile, when the Argentine delegation gifted coins, flags, and soccer balls. Published on March 6, 1953 (a week after Perón left the country), Sepúlveda’s cartoon reflected an important number of press attacks against Peronist meddling in Chile. The image also symbolized the rapid rise and collapse of de la Cruz. In the midst of growing suspicion of Peronist penetration in Chile in August 1953, the Senate removed her from office after discovering she received Argentine money to fund her senatorial campaign.

De la Cruz was not the only Peronist sympathizer. Peronist liaisons in Chile had preferential objectives in the military and labor unions. Among the local adherents frequently targeted by Topaze figured Conrado Ríos (Chilean ambassador to Argentina), Darío Saint-Marie (journalist), and Jorge Ibarra (Ibáñez’s aide-de-camp). The magazine ridiculed their position as sellouts, depicting them naked, dirty, feminized, and fraudulent. Unlike Délano’s burlesque depictions directly targeting the figure of Perón, Sepúlveda’s cartoons employed indirect political humor, with Perón out of the picture. His focus was on those who treacherously sold out Chile through the Peronist policies of Ibáñez’s government. Thus, Topaze’s visual parodies about the Peronist intromission in Chile were just another front for criticizing Ibáñez.

Topaze’s editorial pieces criticized Ibáñez harshly when Chile witnessed rising social unrest. In 1955, Ibáñez implemented austerity policies recommended by the US-based consulting firm Klein & Sacks, which restricted public spending, credit, and wages. Ibáñez’s failure to remedy economic dependence, stagnation, inflation, and poverty only fed social tensions. For Chilean Peronists, social and economic policies compensated for the abuses of an authoritarian regime, pushing Ibáñez to take a repressive response against dissenting voices. Cornered by massive demonstrations, Ibáñez considered the possibility of an internal coup within his administration (autogolpe) to establish a dictatorship in March 1955—a scandal that shook the nation when the press revealed secret meetings between Ibáñez and army officers. In the end, Ibáñez abandoned the plan. Congress created a commission to investigate the infiltration of Peronist elements in Chilean political parties, armed forces, unions, and media. The commission elaborated a detailed report in June 1956 that accredited strong connections between Argentine agencies and a group of Chileans willing to publish favorable news about Peronist Argentina (Acuña Reference Acuña2022).

Apostate, exiled, and childish conspirator

Ibáñez also dismissed the recommendations of the Chilean Peronists because of the unpopularity of Perón as a result of his ongoing confrontation with the Argentine clergy in 1954. Despite Perón’s knowing that church-state relations were a crucial pillar for his New Argentina, he and his wife Eva Duarte (or Evita) expressed anticlerical views in the 1950s. This tension became more notorious after Evita’s death in 1952, as state officials diverted resources to propaganda campaigns aimed at creating worship of Evita as a Virgin Mary–like “Spiritual Leader of the Nation.” The foundation of Argentina’s Christian Democrat Party did not contribute to diminishing this antagonism as it looked for support among Catholic workers and families (Bianchi Reference Bianchi2002). In response, Perón launched a strong offensive in November 1954, prohibiting religious education in public schools, authorizing divorce, and opening brothels. A few days before Christmas, the government prohibited religious processions in the streets and imprisoned several Argentine priests for public disobedience. The attack on the Argentine church became a favorable occasion for a Chilean protest against Perón (Figure 10).

Figure 10. René Ríos (“Pepo”), untitled, Topaze, no. 1153, November 19, 1954. The text is as follows—Sancho: “Now his days are counted, for not having remembered that My lord Don Quixote suggested not battling with the Church.”

Although Topaze usually made fun of priests, cartoonists saw the church problem in Argentina as an opportunity to attack Perón. On November 19, 1954, Topaze published a complex cartoon elaborated by René Ríos (“Pepo”), one of the creative forces behind the magazine in the 1950s after reaching fame with Condorito (a comic strip series created in 1949 that became very popular throughout Latin America). The cartoon featured three characters: a priest dressed in a black cassock running away from an enraged Perón, who chases him with a saber in front of a peasant who witnesses the scene. The fatness of the priest was a common visual metaphor that represented the church’s power and wealth in Chilean society. However, the center of the parody revolves around Perón, who aggressively pursues the priest. The cartoon’s language directly references Don Quixote’s loyal companion Sancho, suggesting that Perón had made a big mistake by repressing Argentine priests. What Ríos suggests through Sancho’s commentary is the danger of fanaticism. In this case, blind faith in Peronism could result in violence against the clergy. Perón’s image as a madman chasing the priest is a means of questioning blind, uncritical (political) faith. Like Cervantes’s Don Quixote, Topaze understood quite early that going after the church was political suicide, denouncing the conflict not to defend the interests of the church but to highlight the authoritarian measures imposed by Perón, warning Chilean readers that the Argentine regime had reached a point of no return. Here, visual absurdity and the commentary offered by the Sancho-like speaker interface with Perón’s lack of democratic credentials that the magazine aimed to critique. Editors mocked Perón as a “false messiah” or “apostate” and denounced his anticlericalism as an attempt to “suffocate Catholicism.”Footnote 4 Images of Perón confronting the pope or Jesus symbolized the regime’s bold attitude. Images alluded to the growing tensions between Perón and the Vatican that culminated with Perón’s excommunication in 1955.

With Argentina’s foreign policy paralyzed, Chilean authorities did not raise voices against the coup that ousted the Peronist regime on September 16, 1955. The crisis between the church and the Peronist state hindered a defense by Chilean Peronists, who were under public scrutiny for collaborating with a foreign government. Ibáñez had already taken a position in favor of the church and was subtly moving away from his previous alliance with Perón, despite that the local opposition continued accusing him of being Perón’s puppet (Maggi Reference Maggi1957). The new conservative military junta governed Argentina autocratically until new elections were held in 1958. To mitigate local resistance, the new dictatorship outlawed the Peronist Party and prohibited the display of Peronist iconography in public spaces.

While the 1955 coup had tremendous effects in Argentina, it did not bring important changes to Topaze’s visual representation of Perón. On September 23, 1955, an editorial expressed pride for Chilean journalism as one of the main combatants of Peronism in Chile, arguing that “the press always fought that absurd doctrine…. The Argentine people certainly did not deserve the destiny offered by the Peronist megalomania.”Footnote 5 While editors lamented another state coup, they conceived the fall of Perón as part of an ignominious military presence in Argentina. Furthermore, Topaze did not abandon the fascist tag and described Peronism as “one of the most absurd social endeavors of contemporary history.”Footnote 6 At the same time, the portrayal of Perón as the local version of European fascism continued to be useful as a visual stereotype (Figure 11).

Figure 11. René Ríos (“Pepo”), “To Paraguay,” Topaze, no. 1198, September 30, 1955. The text is as follows—Hitler: “He was luckier than me … Paraguay was too far away.”

On September 30, 1955, Topaze featured Perón escaping from the bombing of the Plaza de Mayo and running to Paraguay. On top of the image and emerging from the smoke, Hitler’s troubled ghost points out that Paraguay was not an option for him. With a tiny image of Perón running for his life and a ghostly representation of Hitler regretting his misfortune, Topaze minimized Peronism as a dying political force in Latin America. The image of a small Perón escaping Buenos Aires, leaving behind his hat and holding his suitcase (implying that he was escaping with money), was in contrast to Topaze’s previous representations of Perón as a sturdy athlete and seductive soldier. Perón’s scared expression resembles that of the priest running. In the chosen illustrations, Ríos focuses on figures in crisis and conflict (e.g., running, chasing), who are then described by a figure outside the action providing comic relief to a delicate situation (e.g., Sancho’s narrative in Figure 10; Hitler’s interior monologue in Figure 11). Ríos staged the fall of Peronist Argentina in conspicuous terms to raise awareness among Chileans who feared the possibility of a military uprising. Although less fearful of Peronism after 1955, Topaze mocked Perón’s fate and pictured his exile as a constant escape, typical of a former dictator in distress. Writers dedicated couplets to celebrate the “fall of the tyranny” and “the death of justicialismo,” and cartoonists teased Perón as a coward who took asylum under dictators.Footnote 7

After his departure in 1955, Perón did not disappear entirely from the public eye. He was still firmly ensconced in the Chilean imaginary as a bad influence in the neighborhood. Topaze illustrators in the late 1950s could barely contain their amusement at how Perón had become an exile trying to exert some influence over Latin American leaders. In a big cartoon, Ríos poked fun at Perón’s late attempts to convince Ibáñez to take an authoritarian stance. The image depicted all the Latin American presidents as children in the playground (Figure 12).

Figure 12. René Ríos (“Pepo”), “In Panama,” Topaze, May 11, 1956. The text is as follows—Peroncito: “Che Carlitos! Don’t be silly! Take the ‘straight line’ and go play pirates with those kids. Those on the other side are boring …”

Published on May 11, 1956, the cartoon shows Perón urging Ibáñez to join the group of five children playing pirates and bullying a girl who symbolized democracy. The “pirates” included dictators Gustavo Rojas-Pinilla (Colombia) aiming with a slingshot, Marcos Pérez-Jiménez (Venezuela) carrying a sword, Fulgencio Batista (Cuba) holding the girl’s right braid, Rafael Trujillo (Dominican Republic) holding the girl’s left braid, and Anastasio Somoza (Nicaragua) pulling the rope. Pointing toward the action, Perón suggests that joining the pirates could be far more exciting than hanging out with the boring elderly, embodied in the image from left to right: Dwight Eisenhower (United States), José Velasco-Ibarra (Ecuador), and Juscelino Kubitschek (Brazil). Ríos’s cartoon showed Perón whispering to Ibáñez, inviting him to take the “straight line” and assume a more authoritarian stance. The mention of the straight line was not accidental but a reference to the group that tried to convince Ibáñez to carry out an internal coup. Although Ibáñez had abandoned the plan and conspirators were under investigation, Topaze reminded readers that Ibáñez had a history of conspiracies and authoritarian tendencies.

While Ríos’s cartoons provided dynamic representations of Perón, certain visual elements were in dialogue with the first characterizations sketched by Délano in the 1940s. The playground cartoon returned to the initial visual trope of childhood as a parody of Latin American democracy, highlighting the maturity of the United States, Ecuador, and Brazil over the Central American and Caribbean nations. The old men sitting on a chair represented the weakness of democratically elected rulers, who simply witness how the bad boys harass democracy, depicted as a bullied little girl. Ibáñez and Perón share an intermediate place as adolescents debating their transition to adulthood. Although Perón and Ibáñez dress like the elderly sitting on the bench, with long robes and bare legs, both appear with toys in their hands (Perón is holding a palette, and Ibáñez is playing the traditional Chilean cup-and-ball game emboque). While Perón points his finger to the bullying children, glancing sideways at Ibáñez, the latter turns his back on them, expressing some degree of resistance to joining the pirate side. Encouraging Ibáñez to “play with democracy,” Perón appears as a restless child instigating coups throughout the continent.

Conclusions

In a compilation of his drawings published in 1955, the famous anti-Peronist cartoonist José Antonio Ginzo (“Tristán”) (Reference Ginzo1955) outlined a definition of political humor: “I hope that these anti-dictatorial and anti-Peronist caricatures provoke something more than a smile. Hopefully they provoke some reflections. Because these are terribly serious caricatures.” Ginzo’s commentary defined political cartoons as serious artifacts, beyond mere laughter. What Ginzo perhaps never imagined is that cartoons could play a role outside national borders, as many of his Chilean colleagues crafted new versions of Perón and Peronism that borrowed from anti-Peronist Argentines. Compared to the comical depictions of Perón produced by Argentine opposition media in the 1940s, which revolved around the opposition between fascism and antifascism, what we find in Topaze is the incorporation of new local elements and “microintentions” that responded to specific events and personalities in Chile. In light of the unavoidable links between populism and nationalism, Topaze highlighted a sense of shared identity against dictatorship that appealed to middle-class readers. It did this without articulating an antiestablishment and antielite discourse and instead addressing readers’ fears and frustrations, such as economic insecurity, political marginalization, and national pride. Topaze’s imagery might have tapped into these sentiments by presenting itself as a representation of Chile’s interests against foreign influences, building a sense of unity through satire. In the early 1940s, Topaze depicted the Argentine dictatorship as militaristic, authoritarian, and fascist—labels that paved the way to adopting a definitive anti-Peronist stance. In the early 1950s, Topaze illustrators provided polysemic versions of Peronist Argentina that looked remarkably similar to Chile under Ibáñez. Cartoonists focused on press independence, which, according to the magazine, was absent in Peronist Argentina and potentially under risk in Chile after the election of Ibáñez in 1952.

Peronist Argentina became a useful visual metaphor to make Chilean viewers understand not only Argentina’s context but also their own. Perón was often represented next to Chilean politicians and rarely alone. Therefore, his presence was relational and responded to Chile’s involvement in global conflicts such as World War II and the Cold War. Indeed, Peronist Argentina became a major political issue in Chile’s press, awakening the fears of the nation’s most fervent anti-Peronist sectors from both the Left and the Right, even to the point of creating a congressional commission to investigate Peronist maneuvers in Chile. Perón’s departure in 1955 did not provoke a decline in Chile’s attention to Argentina, and stories about Perón’s whereabouts were frequent in the press. For Chilean readers, understanding cartoons about Peronist Argentina involved a series of complex imaginary border crossings in which audiences created their own visual perception of the figure of Perón. Unfortunately, it is difficult to trace readers’ response because Topaze rarely included a section for letters sent by subscribers, limiting their voices within the magazine.

The periodization chosen for the study reflects the peak of Perón’s presence in the public eye before the end of the Ibáñez administration. In that sense, the frequent depiction of Perón was a primary component of Topaze’s distaste for authoritarianism and central to the magazine’s neutrality. Arguably, during the years encompassing the Ibáñez government, Topaze used Peronist Argentina to project the dangers of authoritarianism, favoring a period of restructuring within the system, a transition between a model of party-based coalitions and a model in which populist projects predominated. It is this shift that Topaze attempted to explain through visual parodies with Perón in the spotlight, reflecting a mismatch between the Chilean party system and a new era of mass politics. As the Ibáñez administration weakened due to successive street demonstrations, Chilean media gradually showed less interest in Perón. This does not imply, by any means, that Perón disappeared from Topaze in the 1960s, especially considering the transformations within Peronism itself. For example, in its editorial of July 1, 1966 (just after the coup that toppled Arturo Illia in the so-called Revolución Argentina led by Juan Carlos Onganía), Topaze suggests: “Peronism is a popular movement. However, the reactionary groups have carried out all kinds of maneuvers to outlaw this group that, by a strange paradox, constitutes a large part of the Argentine mass.”Footnote 8 Topaze adjusted its approach taking a pro-Peronist stance in the sense that successive military coups interrupted the restoration of democracy. In that 1966 issue, Topaze published a cartoon featuring an older Perón awaiting Illia’s arrival in exile. Here Perón was used to champion democracy as a leader whose government ended by a military coup. Whereas in the 1940s and 1950s anti-Peronism was antiauthoritarian and antifascist, in the 1960s anti-Peronism became a way to repress popular organization.

As Perón faded from the pages of Topaze, so too did the magazine’s sales. Délano and Ríos collaborated only sporadically as each focused on individual projects in the 1950s. The apparition of El Barómetro, led by former Topaze members Luis Sepúlveda and Luis Goyenechea affected Topaze’s place as the leading satirical magazine. In 1957, the businessman Gonzalo Orrego bought the magazine; it later became the property of a group led by Christian Democrats in 1963, who controlled the magazine until its closure in 1970.

Influenced by the creativity of talented illustrators, visual interpretations of Peronism in Chile developed according to local cultural criteria. The cartoons examined here cover only a part of a wide spectrum of interpretations of the Peronist phenomenon in Chile from the daily press and essays of the time. The decisive anti-Peronist stance to denounce foreign penetration not only lost public interest in the following decade; the entire focus of the discussion on foreign interference would turn to the United States. Abundant research has demonstrated how the Central Intelligence Agency pumped millions of dollars into the conservative daily El Mercurio to spearhead a propaganda campaign against Allende’s government in the 1970s. The small presence of Perón in the satirical magazine became disconnected from Chilean politics, placing the cartoonists in an awkward position to keep using Peronist Argentina as a useful visual parody.

Acknowledgments:

Financial support for this article’s research and writing was provided by Chile’s FONDECYT Postdoctoral Program (Project No. 3200023). My special gratitude to María Elisa Fernández at the University of Chile and the three anonymous LARR reviewers for their help in reading and commenting on various drafts of this article. I also thank the staff at Chile's Biblioteca Nacional and the digital collections team of Memoria Chilena (www.memoriachilena.gob.cl).