Eduardo grew up in a small city in Brazil, part of an economically vulnerable family but steeped in traditional middle-class beliefs and desires.Footnote 1 He resented the injustice of class hierarchies and worked to create economic and political opportunities for himself and other vulnerable and poor Brazilians. As his economic position stabilized under the Lula presidency, and then as Brazil entered a recession, he grew critical of progressive politics. The demands he once supported and the protests he once joined came to strike him as a destruction of the social fabric by “those people”—members of the lower classes whom Eduardo now considered ill equipped to occupy the spaces of the educated and cultured.

Eduardo’s experiences and perspectives illustrate the position of the traditional middle classes in Brazilian society and their views of class changes over the past several decades. Brazil is historically a highly unequal and hierarchical society, but in 2002 a cross-class alliance of voters elected a former metalworker, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, to the presidency with the hope of change. Under Lula’s Partido dos Trabalhadores (Workers’ Party, PT), innovative fiscal, social, and developmental policies, alongside high commodity exports, resulted in economic growth and enabled over forty million people to move out of poverty. The upswing was followed by an equally dramatic downturn. The PT became mired in corruption, in its inability to sort out public mismanagement, and in a crashing economy; a “new right” mobilized, the oligopolistic media went on the offensive, and the public resoundingly voted the PT out in the 2018 presidential elections (see Saad-Filho and Boito Reference Saad-Filho and Boito2016).

This article uses Eduardo’s story as a window on the tensions between the traditional middle and the so-called new middle classes through an accidental biographical ethnography. The method is accidental because we reinterpreted an existing field journal; we call it biographical ethnography because we use one person’s story to understand broader trends. The textual product of this analysis deviates from the structure of a traditional social science article because we intersperse biographical passages with theoretical analysis. By juxtaposing Eduardo’s perspective of sociopolitical events with our own analysis, we aim to share his voice and to critically examine its implications.

The article begins with a methods discussion. Then, the first biographical passage traces Eduardo’s history, economic vulnerabilities, and mélange of leftist activism, disdain for poverty, and denial of racism, until the moment he lands a job in Lula’s federal bureaucracy. This is followed by an analysis combining economic, sociological, and cultural indicators to construct an understanding of the Brazilian traditional and new middle classes and recent changes in class mobility. This suggests that Lula’s newly nonpoor did not form a new middle class but rather expanded a vulnerable class between the poor and traditional middle classes. The second biographical passage details Eduardo’s turn against Lula’s policies. The corresponding analytical section embeds this shift in the historical tensions between the traditional middle and lower classes and the disjunctions of Brazilian democracy. In the final biographical passage, Eduardo contemplates the vulnerable demanding access to spaces traditionally reserved for the traditional middle classes. The related analytical section argues that discriminatory tendencies restrict the openness of the middle classes to class mobility. In sum, in tracing Eduardo’s trajectory, we attempt to understand who the traditional middle classes are and argue that their position vis-à-vis the lower classes is complex: their consciousness/denial of inequality and injustice, is central to the construction of Brazilian society.

Methods: Accidental biographical ethnography

In 2015, Hilgers hired a white Brazilian man who had just finished a year of doctoral studies at an American university as a research assistant (RA), tasking him with keeping a field journal of interviews and observations in a Brazilian favela. Later, rereading the journal, she realized that the personal anecdotes about politics and society interspersing his notes were interesting for their commentary on Brazilian class relations. The RA was Eduardo, and the present study is an accidental biographical ethnography.

According to Poulos (Reference Poulos2016), accidental ethnography is a habitual poking around, seeking knowledge through systematically keeping one’s eyes open, taking notes, questioning, and looking for how things fit together in a story that interprets life. The autoethnographic nature of Poulos’s work makes constant note-taking his methodological focus, but his insights also apply to other approaches. Researchers in the field can “turn ‘non-data’ into data by paying systematic attention to unplanned or ‘accidental’ moments” (Fujii Reference Fujii2015, 526). Targeted data collection is surrounded by the daily life that shapes the researcher’s contextual understanding. Taking note of time spent “navigating a social environment” and analyzing these lived moments alongside the focused research generates stronger theory (Fujii Reference Fujii2015, 527).

While Poulos and Fujii both focus on accidental autoethnography, our approach is accidental biographical ethnography. First, our ethnographic selves have an impact (Coffey Reference Coffey2009) because our interests triggered our response to Eduardo’s reflections. As accidental ethnographers, we are open to exploring such triggers (Poulos Reference Poulos2016). Second, as biographers, we are outsiders studying Eduardo’s field notes and conversing with him to learn his life story and perspectives. Third, we use Eduardo’s story and the sociopolitical position in which he establishes himself as a view on the Brazilian middle classes. Our primary interest is not Eduardo as an individual but Eduardo as a member of a particular group of people at a particular moment. For Herzfeld (Reference Herzfeld1997), this is ethnographic biography. It is biography because it deals with the life and ideas of one person, but ethnography because its focus is not the person whose life it recounts but the context whose meaning that person’s experiences help to interpret. Herzfeld (Reference Herzfeld1997, 2) uses ethnographic sources to construct the context and the person’s perspective “to overcome the distance between social analysis and lived experience.” In our case, the evidence establishing group characteristics and the moment is built from secondary histories, theories, surveys, and ethnographic field notes from other projects running from 2015 to 2020. We consider the paper an ethnography because our “use” of Eduardo is to explain a phenomenon by viewing society from the subject’s point of view (Geertz Reference Geertz, Martin and McIntyre1973). Because we see the method as primarily ethnographic, we invert Herzfeld’s phrase to arrive at “biographical ethnography.”

The biographical ethnography also structures the “textual product” (Jones and Rodgers Reference Jones and Rodgers2019, 305–306). In including passages of Eduardo’s history and observations interspersed with theoretical analyses based on other ethnographic and secondary data, we give the reader unfiltered access to Eduardo’s perspective as well as to “its wider ramifications and how it reflects broader dynamics” (Jones and Rodgers Reference Jones and Rodgers2019, 305). By “showing rather than telling” (Auyero and Berti Reference Auyero and Fernanda Berti2015, 17), we share Eduardo’s voice, presenting events as he has seen and lived them. Yet it remains important to contextualize the meaning of ethnographic data. This task is uncomfortable when the resulting analysis is critical of study participants’ behavior (see Auyero and Berti Reference Auyero and Fernanda Berti2015; Bourgois Reference Bourgois2003). While Eduardo interprets the turn away from PT politics as Brazil’s awakening, we see it as the result of a conjuncture of events including the traditional middle classes’ ambivalence vis-à-vis the less well-off. But, rather than presenting only fragments of Eduardo’s thoughts to underscore our arguments, we give the reader the opportunity to understand his perspective. This is “social science … written in a different way” (Gay Reference Gay2005, xxii).

Data gathering and analysis developed iteratively. After identifying passages reflecting class relations in Eduardo’s journal, we met with him for a “long interview” (see McCracken Reference McCracken1988) to establish biographical details and encourage him to develop his narrative.Footnote 2 In subsequent virtual interviews and emails, we dug into ideas that emerged as our understanding of Eduardo’s situation deepened and as we were writing the paper. Research, analysis, and writing became an interactive process, extending into the article review phase.Footnote 3 Eduardo did not participate in the writing of the paper, but he has read drafts and has graciously allowed us to use the material as it is presented here.Footnote 4

Eduardo’s positionality crystallized through the iterative research/writing/review process. It gradually became clear that his economic vulnerability was similar to the fluxes experienced by many people who are neither poor nor secure. While the specificities of Eduardo’s trajectory are unique, the overall pattern fits one of teetering between vulnerability and security. Millions of Brazilians are at the mercy of national economic growth curves and household-specific shocks such as a death or the loss of a salaried job, as is the case for those subsisting on the line between poverty and vulnerability (see Birdsall Reference Birdsall2015). Upward status swings allow for positive changes such as education, but downward swings mean experiences of insecurity in income, food, and housing. Eduardo also demonstrates some of the contradictions of Brazilian race/class relations. An educated and politicized white man, he understands class and race as powerful and violent social constructs but reproduces them. This duality is integral to the traditional middle and privileged classes’ construction of Brazilian society (see Holston Reference Holston2008; Caldeira Reference Caldeira2000).

Eduardo: Struggling to be in the middle classes

Isobel, Eduardo’s grandmother, grew up illiterate in the small city of Derrota, São Paulo, and married Socrates, a bank account manager twice her age who had migrated from the Northeast in rebellion against his wealthy family. His job allowed for a middle-class house and contact with the city’s businesspeople, and Isobel volunteered for a samba school. The first of their five children, Maria (Eduardo’s mother), attended public school and studied psychology at a private university, having convinced Socrates that psychology was like medicine and, therefore, a route to wealth.Footnote 5

Lucia and Tony Sr., Eduardo’s grandparents on his father’s side, are descendants of Italian immigrants forced into indentured labor on the Derrota-area coffee farms. Tony Sr. abandoned agriculture for construction in the 1950s, and he and Lucia moved to the city when they married. But it was a loveless relationship, and Tony (Eduardo’s father) was an unwanted child. The first family member to attend college, he dropped out and became a drifter.

Maria and Tony’s marriage played out in the 1980s, Brazil’s “lost decade” of debt crisis, inflation, and economic insecurity (see Vidal Luna and Klein Reference Vidal Luna and Klein2014). The couple moved to São Paulo in search of work, sending Eduardo (born in 1981) to live with Isobel and Socrates. When Tony started a brick production in Derrota—“one in a series of harebrained schemes”—the family moved to a working class neighborhood “on the other side of the tracks,” far from shops and schools, among warehouses and empty lots. Socrates’s death mid-decade left Isobel living on his pension and Maria supporting her own household on earnings from tutoring the children of Socrates’s business contacts, who also arranged for Eduardo to receive a private school scholarship. Whenever money came in, Maria rushed to buy food before prices increased. The family eventually managed to move to a middle-class neighborhood, but Maria and Eduardo were evicted when Tony left, and they moved in with Isobel.

Among Eduardo’s fondest memories of these years are the pre-carnaval samba school gatherings at Isobel’s house. “Grandma had all these people in her house, black people, aboriginal people, LGBTQ people, they were all there…. She would give them food; they were like her kids.” Although he would also visit these friends in their homes in the poor and working-class neighborhoods, race was never discussed in his family. “So in my personal experience [race] was never an issue. I feel that there is an imported racial discourse in Brazil now that doesn’t really fit … everyone is mixed.”

At school, Eduardo was a “charity case,” “a pariah.” “I lived in one universe, but studied in another universe…. People from school were traveling to Disneyland, filthy rich. It was interesting to see what they had access to and I didn’t…. I wasn’t really friends with rich kids.” At least school gave him structure, with Maria working all the time and Tony gone for long stretches before disappearing altogether. “I don’t remember being very well taken care of.” And the bullying only worsened. Derrota is “a backwards country town … but I listened to Nirvana and read literature.”

My mom would do these jobs in São Paulo…. She would take me with her and drop me off at a shopping mall and pick me up at night…. I was like eleven, twelve years old. So I grew up in [a bookstore] … and record stores…. I would just spend the day in a shopping mall and eat McDonalds. I wouldn’t buy anything because I didn’t have the money. But sometimes I’d have the money to buy a CD or a book or to see a movie.

Maria also taught Eduardo about politics. “She took me to the … protest in Sé against the dictatorship” in 1984, when he was a toddler, that was part of the Diretas Já movement demanding direct presidential elections (see Rigue Reference Rigue2014). In 1992, Eduardo demonstrated in support of the impeachment for corruption of the first openly elected president since the military dictatorship, Fernando Collor de Mello (see Brooke Reference Brooke1992).

By the mid-1990s, the Washington Consensus–influenced Plano Real succeeded in lowering inflation and stabilizing the economy (see Vidal Luna and Klein Reference Vidal Luna and Klein2014). Maria found a salaried job in another city that paid for rent in a middle-class neighborhood, fees at a new private school for Eduardo, and eventually his travel to spend a year with an aunt in New York. These were good years, though there was “no money left over at the end of the month.” When Maria moved back to Derrota to do contract work for the city, she was able to buy a lot in a middle-class housing development but “couldn’t afford bricks … so she’s a weirdo because she lives in a wooden house.” Eduardo finished high school in the public system, using the money that would have been spent on private school fees to attend a preparatory course for public university entrance exams.

Not making the public university cut, Eduardo began to study law at a private university in São Paulo in 2000. To help pay for tuition and living expenses, he taught English in locations across the city. He disliked law school and the other students, and “because I was always in a razor blade between rich and poor, my sense of class, social conflict was always very clear, my sense of politics…. I signed up to be a member of the Workers Party and went to the meetings.” A year later, he took the vestibular again and was admitted to social science at the public Universidade de São Paulo. “In 2001, for the first semester, I’m doing both universities at once and working. Thinking that all the rich people, all they do is study and go home and watch TV. And I’m barely staying afloat.”

Frustrated, he went to live with a Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais sem Terra (Landless Workers’ Movement, MST) community, to work the fields, cook, and teach grammar and history. He heard stories about the community and its origins: the members had camped on land next to a highway and been terrorized by the landowner but eventually won access to the land under the constitutional clause calling for the redistribution of unproductive plots.Footnote 6 Realizing that “the revolution would need to come from below,” Eduardo decided to drop out of law school to focus on the social sciences and on researching “revolutionary social change.”

When Lula was elected president in 2002, Eduardo “wanted to be part of what Lula meant to Brazil.” He began a prep course for a concurso público—a competitive selection process for the public service (see Cavalcante and Carvalho Reference Cavalcante and Carvalho2017)—with the idea of making a difference from within Lula’s administration. He says, “2004 … was the worst year of my life because I had four or five jobs at different schools, commuting, and then I would go to USP at night and prep school on Saturdays, and Sunday was the day to study…. I’d eat only once a day at a subsidized restaurant at USP. I lost fifty pounds.”

Maria’s income had decreased again, but she took Eduardo in when he hit rock bottom. A year later, “when I heard that the Ministry of Social Development is hiring, I decide to go for that. I had to take the exam in Brasília, but couldn’t afford to go there,” so he borrowed money from his girlfriend’s family. Making the level of technical advisor, Eduardo moved to Brasília in 2006 to work for the Ministry of Social Development, which ran anti-poverty programs including the conditional cash transfer Bolsa Família.Footnote 7 He held several positions, including one as coordinator for the unionization of waste pickers. “I was going to the neighborhoods next to the garbage dump … just imagine this valley and that’s where the dump is and all of these poorly constructed homes and dirt streets next to it…. They were living there, they were working, just trying to stay afloat as best as they could.”

Eduardo enjoyed his work: “I was rich … working for the government.” His final salary was almost 7,000 reais (US$1,680) monthly. Because Maria’s fortunes improved again during this period with the commodities boom, he could keep most of his salary for himself. This allowed him a previously unknown standard of living; he was “able to support a [rented apartment] and buy food on the same paycheck … books, movie tickets, restaurant outings and, after having saved enough, a used car.”

Income, identity, and the fluidity of the middle classes

Eduardo grew up straddling class divides. Socrates provided Maria access to business elites, but his position was not enough to give her financial security. She moved between precarious self-employment and salaried work, her prospects fluctuating with the country’s economy. On Tony’s side, there was no family security. Eduardo was educated at private schools and a public university—hallmarks of traditional middle-class prestige (Balbachevsky, Sampaio, and Andrade Reference Balbachevsky, Sampaio and Yahn de Andrade2019)—but his access and status were uncertain. His situation only stabilized once he was able to capitalize on his education during the expansion of the Lula years. Despite his years of economic insecurity and mobilization to improve the status of the poor, class and race prejudices are evident in Eduardo’s worldview. Socrates’s socioeconomic position included a house on what Eduardo considers the right side of the tracks, and Eduardo was educated with the traditional middle classes. His portrayal of the poorer carnaval folk as children to the charitable figure of Isobel and his denial of racial problems indicate a privileged position that reproduces blindness to injustice (see Caldeira Reference Caldeira2000).

Brazil has historically been an unequal society with low social mobility, a large and impoverished lower class, and small middle and upper classes (Hunter and Sugiyama Reference Hunter and Sugiyama2009). A conjunction of events in the first decade of the twenty-first century allowed 44.7 million Brazilians to move out of poverty and another 12.5 million to move into the traditional middle classes (Neri Reference Neri2014). The shift arose as social democratic development policies under Lula combined with a global commodities boom to generate investor confidence and consumer spending. Lula continued the liberal economic policies of the 1990s but revamped redistributive policies, creating Bolsa Família, increasing minimum wages, and expanding access to credit for the lower and middle classes. Low inflation rates made borrowing accessible and inspired loans designed to bring lower-income sectors into the credit market, and demand for consumer goods increased. Unemployment decreased by half, and consumer borrowing as share of GDP doubled (Hoefel et al. Reference Hoefel, Kiulhitzan, Broide and Mazzarolo2015; Sola Reference Sola2008; Vidal Luna and Klein Reference Vidal Luna and Klein2014).

By some economic measures, the middle classes expanded massively. The World Bank sets the developing world poverty line at US$2 daily per capita. The millions of Brazilians jumping this hurdle in the Lula period are sometimes labelled a “new middle class” (see Pochman Reference Pochman2012). Their income, and that of the millions more leaving poverty in the rest of the developing world, clustered just above US$2, reducing their immediate hardships but not their vulnerability to poverty (Ravallion Reference Ravallion2009).

Several researchers suggest higher poverty thresholds and identify a sector between poverty and traditional middle-class security to describe the status of the nonpoor. Birdsall, Lustig, and Meyer (Reference Birdsall, Lustig and Meyer2013) set the poverty line at US$4 daily per capita, doubling the $2 line around which income often fluctuates with societal or household context (table 1). The $4–$10 earner range of middle-class “strugglers” is more vulnerable to poverty-inducing crises (20 percent to 40 percent probability over five years) than “secure” middle-class earners of $10–$50 (10 percent probability over five years). Earners of over $50 per day are considered “rich.” Secure middle-class insulation from short-term economic volatility results from health care, pensions, education, and home ownership (Birdsall Reference Birdsall2015).

Table 1. Income categories.

* Authors’ calculation using US$0.24 exchange rate, rounding, assuming months of 30.5 days and household size of 3.3.

** Authors’ calculation using Neri’s figures.

Neri (Reference Neri2014) also creates new class categories but estimates even higher cutoffs, because his analysis is restricted to Brazil (a middle-income country) and his calculation accounts for more than income. It includes the productive assets (human, physical, social) of all household members, because the current and permanent incomes of the resource-sharing nucleus characterize income sustainability. He adds assets such as nonmonetary income (important for the poor) and physical and financial capital (important for the wealthy) to salaries to measure real income. The result is a poverty line of $5 and a “new middle class” line of $21 daily per capita (table 1).

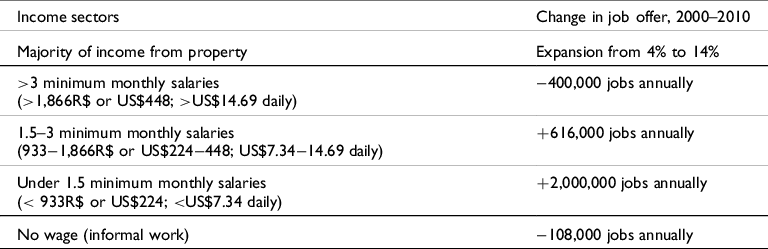

Although poverty decreased in the first decade of the 2000s, the large majority (87 percent) of Brazilians remained poor or vulnerable to poverty (table 1). Most of the economic expansion took place in the service sector, followed by civil construction and extractive industries, and the great majority of new jobs opened in the low end of the pay scale (table 2). While there was also an expansion of the wealthy sector making most of its income from property (land, rent, interest, and profits), the middle-income group stayed relatively stable. The Lula years had a bigger effect on the working classes than on the middle classes (Pochman Reference Pochman2012).

Table 2. Income sector job growth (Brazil).

Table elaborated by authors with data from Pochman (Reference Pochman2012), calculating amounts using the 2012 monthly minimum wage of 622 reais and a US$0.24 exchange rate.

While we support the analysis underlying Neri’s income categories, we argue for the term “vulnerable” to identify class C, to clearly differentiate it from the traditional middle classes’ security and identity. Indeed, the traditional middle classes are different from the vulnerable for reasons beyond the financial security described above.

Sociological income category comparisons show that moving up the hierarchy means increasingly small, educated, and urbanized households, with women more likely employed, all working members more likely to be wage earners than self-employed, and work more likely to be in health, education, or public services than in the primary sector (Ferreira et al. Reference Ferreira, Julian Messina, López-Calva, Ana Lugo and Vakis2013). As their incomes increase, lower classes educate their children, add a level onto their self-constructed homes, and take vacations, but may not have enough to afford traditional middle-class neighborhoods and leisure activities (field notes, 2017, 2018, 2020). They are no longer poor, but, from the perspective of the traditional middle classes, neither are they not poor.

As Eduardo’s case demonstrates, insecurities affect not only those vulnerable to falling back into poverty but also families with incomes and characteristics that sometimes place them in the traditional middle classes but cannot sustain them there. They may fall into poverty (see Birdsall Reference Birdsall2015) or move between the middle classes and the vulnerable, as Maria and Eduardo do. Despite Socrates’s status and Maria’s education, Maria’s work fluctuated between precarious and secure, and there were moments of food scarcity. Even when there was enough money for private school and rent in a middle-class neighborhood, it was not enough to save. This illustrates the complexity of income generating activities. Forty to 63 percent of Brazilians are active in some kind of informal work, and many of them use informal activity as Maria does: to bridge periods of formal work or add to the income from that work (Henley, Arabsheibani, and Carneiro Reference Henley, Arabsheibani and Carneiro2009).Footnote 8 Eduardo keenly felt the difference between himself and his securely established classmates: “I’ve never fallen into the abyss [of poverty], but I’m always looking at it.” At the same time, he has internalized the privileges of his race, education, and grandfather’s heritage.

Our understanding of class is based on indicators including income and education, but also on a construction of identity that involves rights, privileges, and prejudices. Class is “a dynamic process which is the site of political struggle” (Lawler Reference Lawler2005, 430). In the post-authoritarian era, the Brazilian lower classes have mobilized around their constitutional rights to citizenship, dignity, work, and political representation, making these fundamental aspects of their identity.Footnote 9 The traditional middle classes deny lower-class aspirations by defining themselves through narratives of superiority in taste, respectability, critical thinking, merit (Lawler Reference Lawler2005), and race. They are privileged in their consumption of goods and services and in the resource security ensuring future consumption. They are also convinced of meriting their privilege, vis-à-vis undeserving, racialized lower classes. Merit is a cornerstone of the traditional middle classes’ ideology, with members believing that their privileges result from hard work, while lower-class gains are political and therefore undeserved.Footnote 10 Many frame poverty as a racial characteristic, denying the causal effect of slavery and postslavery socioeconomic structures (Lara and Barcelos Reference Lara and Gil Barcelos2020). Alongside economic incentives, these prejudices constrain the traditional middle classes’ openness to political alliances and sharing benefits with the lower classes.

Eduardo and the new right

After two of what would be his five years of employment in the Ministry of Social Development and newfound wealth,Footnote 11 the global financial crisis hitFootnote 12 and Eduardo realized that his socialism had been rooted as much in resentment of the rich as in love of the poor.Footnote 13 Ayn Rand’s Atlas Shrugged (1957) introduced him to individualism and laissez-faire capitalism, and he began to ask

questions that all the Marxist theory I’d read couldn’t answer … the idea that no mob has the right to take your money…. Here I am in one of the biggest states in the world, in the ministry that’s the Robin Hood ministry, and I started seeing that most people working with me were militants and were not really qualified…. These people, in charge of the state, can’t really do anything but discuss Marxism. So slowly I started questioning the ministry. For example: ok, so we’re putting all of these people under our umbrella, can we start talking about an exit door now? … You’re supposed to give people Bolsa Família for the time being, they’re supposed to get out of it, you can’t have people surviving out of welfare. They’re supposed to take care of themselves. But that’s not how our programs work.

This evaluation of the Ministry of Social Development is not supported by the literature, which emphasizes the high caliber of staff and expertise in program construction, especially the internationally acclaimed Bolsa Família (e.g., Sugiyama and Hunter Reference Sugiyama and Hunter2013). Nonetheless, Eduardo began to think that in the postdictatorship era, and especially under the PT, the poor and vulnerable were brainwashed to believe in the existence of unjust hierarchies. One of his field journal entries, of a discussion with a former gang member, is emblematic in this regard.

Like many kids in the favela, [he] was recruited by the drug gangs…. He lived in great poverty in a one-room shack with all his family. He would see all the gangbangers walking around with money in their pockets, gold on their fingers, and girls around their arms, and he wanted it…. I have to confess that I am always wary when I hear this old narrative that lack of opportunity breeds criminality…. Brazil has been taken over by a cultural Marxist ideology … it revolves around pulverizing the nation into victimized minorities, criticizing capitalism and corporate greed and polarizing the society between the enlightened “us” vs. the fascistic “them.” Considering the criminal marginalia of Brazil as freedom fighters … is one of the strongest trends of Brazilian cultural Marxism…. I believe that justifying criminality based on material need is not only disrespectful towards the majority of the population in the favelas who do not choose a life of crime, but also removes agency from the people who do choose to engage in such activities. Brazilian cultural Marxism … has been incorporated into the national school curriculum to the point that the purpose of the teachers in Brazil has shifted: they do not teach math or grammar anymore, they promote “awareness about social conditions.”Footnote 14

Eduardo feels that similar thinking permeated the PT administration: “The ministry was really interesting because it worked a lot like a cult. This is the soft-power ministry. It’s the ministry that’s subverting five hundred years of poverty in Brazil. So all the idealists made their way there and they really operated like a cult. So no questions, everybody in sync, everybody with the same ideas…. This was the night of the living dead, man. There was no dissension.”

Although he felt unable to talk to anyone about his ideas, Eduardo now sees his experience in Brasília as an awakening. He thinks that he grew up “wearing goggles … everything I saw was through Marxist interpretation,” and that his studies amount to little more than “a degree in communism and revolutions” because the left has taken over Brazilian academia.

Eduardo argues that he was not alone in realizing the misguidedness of PT politics. “Now [2016] we have the worst economic crisis in Brazil…. There is no more money to support all these programs. You need business to generate money. Communism doesn’t really work. Look, everybody’s poor.” He attended the August 2015 demonstration in São Paulo, with hundreds of thousands of people wearing the yellow and green colors of the Brazilian flag protesting corruption and the PT. “It’s powerful. You and a million people in Avenida Paulista, singing the national anthem. It’s something that you don’t forget.”Footnote 15 Eduardo thinks that people have realized that state-sponsored inclusion has torn the country apart. “My theory is that extreme left-wing allegiance comes from some deep, internalized resentment. With me, I guess resentment came from that I used to study with the rich kids and I didn’t get to go to Disney and that I was … bullied by them…. It’s misguided resentment.” He sees the anti-PT mobilizations as a “democratic development” expressing a “republican sentiment” among those who are tired of supporting people in “special categories.”

Although a new right coalesced around the 2018 election of Bolsonaro, Eduardo sees the president as a secondary character. When the movement began, “Bolsonaro wasn’t the same … he wasn’t at the forefront of this wave and he has eventually figured out how to surf successfully. He inherited the anti-PT vote, right? He … was just the most successful in occupying that vacuum.” While there are elements of Bolsonaro’s politics that Eduardo opposes—“there is a lot of social conservatism … and I’m not necessarily on board with that”—he does support what he sees as efforts to diminish social conflict by eliminating special treatment of the lower classes.

Disjunctive democracy

As Eduardo matured, he realized that he was not revolutionary but resentful of lacking wealth, and he turned from reading Marx to classical liberal thinkers. He had gay and black friends; was in favor of legal protections of racial, ethnic, gender, and sexual equality; and considered the poor to be honest people working hard to survive. He did not think that the welfare of the poor should be the state’s responsibility, but did not question the merit of his own publically funded university education or his well-paid job, with benefits, in the federal bureaucracy. The ambiguities in Eduardo’s positions reflect those of Brazilian society and democracy.

The traditional middle classes have historically championed citizenship rights when their interests aligned with those of the lower classes (Huber, Rueschemeyer, and Stephens Reference Huber, Rueschemeyer and Stephens1993) but mobilized against the expansion of lower-class rights to protect their property and privileges (Cárdenas, Kharas, and Henao Reference Cárdenas, Kharas, Henao and Dayton-Johnson2015; Fukuyama Reference Fukuyama2012a, Reference Fukuyama2012b). The exclusionary position of the traditional middle classes and the elites play into what Caldeira and Holston (Reference Caldeira and Holston1999) label disjunctive democracy. Brazilian democracy is marked by contradictions in which citizens enjoy free and fair elections and a constitution that protects their rights, but state institutions—bolstered by public opinion—do not protect the rights of the masses.

When Brazilian elites abolished slavery in 1888 and declared the country a republic in 1889, they ensured their dominance through restrictive electoral rules, racist hiring, and repressive policing that barred the lower classes and nonwhites from power (Lara and Barcelos Reference Lara and Gil Barcelos2020; Skidmore Reference Skidmore2010). Industrialization, urbanization, and labor mobilization enabled the nationalist-populist era (1930–1964), during which a series of administrations established state responsibility for national economic development and social welfare. A new urban class structure included the informal sector, manual workers with formal salaries and benefits, a small sector of middle classes of professionals and bureaucrats, and an elite of business leaders usually emanating from landowning families. Traditionalist middle and upper classes, fearful of lower classes’ increasing claims of rights, vilified nationalism and populism in the media but experienced only brief moments of success in forcing liberal policies until 1964, when the announcement of presidential decrees including land expropriation and oil refinery nationalization threatened their property rights and they united behind a military coup (Skidmore Reference Skidmore2010; Bresser-Pereira Reference Bresser-Pereira2017; Holston Reference Holston2008).

The military technocratic regime (1964–1985) was paradoxical. It ruthlessly repressed its opponents, and the fruits of its mixed liberal-developmentalist policy increased income and spatial inequalities, accruing to large landowners and the industrial center-south. But it also oversaw the expansion of citizenship. Although party competition and electoral outcomes were controlled, voter registration and participation increased. Mobilization for access to resources deemed nonpolitical aspects of modern society was also permitted, allowing the poor living in the urban peripheries to expand their demands for rights to the city. By the 1980s, the increasingly confident lower classes set their sights on free and fair elections, joined by middle classes and elites wanting to appear modern on the international stage. Alongside military reformers, they brought about redemocratization (Skidmore Reference Skidmore2010; Bresser-Pereira Reference Bresser-Pereira2017; Holston Reference Holston2008).

In the current democratic period, citizenship rights continue to evolve unevenly. Civil society successfully demanded guarantees of social and labor rights and participation in urban politics in the 1988 Constitution. However, land reform, opposed by the privileged, remained limited, and human rights protections have been difficult to put into practice. Advances are clear in affirmative action and in support of programs and NGOs, civil society organizations, and unions for groups marginalized on the basis of gender, race, ethnicity, sex, work, and geography. There are also improvements in life expectancy, child mortality, access to clean water, and in participatory processes in urban politics and planning. But inequalities remain stark. The gap in quality between public and private education and health care continues to grow. The lower classes know that the courts—which they can neither understand nor afford—are biased toward the wealthy. Police abuse and kill in low-income communities to root out gang members, and in this way contribute to soaring crime and violence rates. A traumatized public—including the poor who bear the brunt of the abuse—supports harsh policing and vigilante justice, criminalizing poverty and race (Caldeira and Holston Reference Caldeira and Holston1999; Skidmore Reference Skidmore2010; Hilgers and Macdonald Reference Hilgers and Macdonald2017). At the same time, continuing current accounts deficits restrict available funding for long-term development programs that could help the lower classes to gain economic stability. Economic downturns (and inflation) quickly affect the lower classes, who operate in cash and have no reserves (Bresser-Pereira Reference Bresser-Pereira2017; Skidmore Reference Skidmore2010).

A good number of advances were made under the PT in power, but the party’s promises to change the structure of Brazilian society and politics failed and eventually resulted in its demise. When students protesting public transit fare hikes in 2013 met with violent police oppression, the middle classes took to the streets in anger against the general context of politics-as-usual in the midst of public administration failures in security, health care, education, and transportation. Lula’s successor, Dilma Rousseff, managed to win another election but faced economic crisis. Commodity demands had declined after the world financial crisis, and financial security, spending, and growth became unsustainable. When the economy collapsed and a massive corruption scandal broke in the media in 2014, PT support crashed. While 52 percent of Brazilians had been satisfied “with things in Brazil today” in 2011, by 2014 72 percent were dissatisfied (Pew Research Center 2014). Mass demonstrations ensued in 2015 and 2016, with 65 percent of Brazilians favoring an impeachment process (Datafolha 2015). Brazilian politics was notoriously corrupt, the PT was caught playing the game, and the public felt betrayed. For the first time, corruption topped health care, education, and employment in the public’s listing of the country’s problems (Datafolha 2015). The public’s anger focused on politics-as-usual (Taylor Reference Taylor2020), merging into a heterogeneous new right that would eventually support the 2018 election of Jair Bolsonaro (Saad-Filho and Boffo Reference Saad-Filho and Boffo2020).

Beyond corruption, reasons for discontent among the new right varied. The vulnerable and lower middle classes feared falling into poverty. In 2016, 68 percent of Brazilians expected to lose their jobs, 49 percent judged their income insufficient to maintain living standards (up from 35 percent in 2013; Latinobarómetro 2013, 2016), many had difficulty repaying credit (Neri Reference Neri2014; Trinkunas and Penfold Reference Trinkunas and Penfold2016), and they blamed the PT (Singer Reference Singer2018). The traditional middle classes had been uneasy with the costs and effects of PT social policy. Their privileges were threatened by changes such as labor rights for informal workers that not only shrank the pool of exploitable labor, but also gave workers the financial resources to consume in previously reserved spaces (Singer Reference Singer2018; Saad-Filho and Boito Reference Saad-Filho and Boito2016; Cavalcante Reference Cavalcante, Velasco e Cruz, Kaysel and Codas2015). As much as the middle classes may claim support for policies such as affirmative action in the abstract (e.g., Vidigal Reference Vidigal2018), their reaction to poverty and race penetrating their spaces is clear.

Eduardo and discrimination

Eduardo has ambivalent feelings about the struggles of the lower classes. In the first entry of his field journal, he describes his thoughts about going to a favela complex:

Today I had my first foray into [the favela]. I have to confess that I was freaking out a little bit before going there. You know, favelas are mired by the stigma of criminality and violence, and as a member of the white middlish class in Brazil, I have to reluctantly confess that I subscribe to that narrative. I mean, why wouldn’t I? I’m sure it’s true that most of the inhabitants of favelas are hardworking, upstanding citizens who just happened to draw the short end of the stick in living in an underdeveloped nation. But it is also true that the amount of criminals per capita is much higher in a place such as [the favela] when compared to the majority of other places in the country. It is, therefore, reasonable to assume that [the favela] is not the safest of places for one to be. So, since I had no intention of joining the statistics, I needed to come up with a contingency plan. I studied the maps and my path like crazy so that I wouldn’t look so lost walking around the favela. I also decided to leave my phone and wallet at home and to hide some change inside my shoes just in case I needed some extra funds for the bus back. So, armed with an ID, a bus pass, and my notebook, I started making my way to the favela…. [The street leading into the favela] is sided by tall constructions of three to four floors, which, combined with the steep hill, gives you the clear impression of being engulfed by the favela. Even the sun darkens a little as you enter.

Adding to his justification of these feelings, Eduardo says, “just to illustrate, [the television series set in the favela] is the sole reason that a lot of my friends, who wouldn’t get caught dead inside a favela, think that it is ‘pretty cool’ that I am doing research in [the favela].”

Although Eduardo came to feel relatively safe in the favela’s busy commercial district, he says that the social conflict created by the rise of wealthier favela inhabitants—the vulnerable class—bothers him.

There’s an old middle class in Brazil. These people are usually white, usually privileged, and they have privileged spaces … in society. So, they … have shopping malls. It’s not that the malls are blocked off for other people, it’s just that other people don’t go there because they know it’s not their place…. During the Lula years, there’s a new middle class that emerges. These people used to be dirt poor…. But now they have access to things that they never had.

These people who grew up with this narrative that they’ve been stepped upon for five hundred years, suddenly they feel empowered and they want some recognition…. The new middle class, these people, whether they have money or not, to consume the products in the special, rich people’s malls, they go there, and they walk and they party there and they go around. They want access to the space.

A few years ago … there was rolezinho [little stroll/excursion]…. A bunch of kids who watch TV, who see the products, kids who belong to funk culture, they went to this shopping mall and there was a problem because there were like three hundred of them at the same time. These kids who come from the favela, who dress like they come from the favela, coming into a mall, singing funk songs. So what happened was that the Brazilian SWAT team was called, and they were beaten out of there. There are two sides of the story. Yes, they shouldn’t be beaten out of there, but at the same time, there were three hundred people at the same time in a shopping mall, singing loudly. And honestly, they don’t really know how to behave in these public spaces, because they’ve never been part of it, so it’s not like it was unjustified to kick them out. But at the same time you don’t call the SWAT team to do it…. A lot of people thought they had it coming. In many ways they had it coming.

Eduardo thinks that demands for better services are legitimate. For instance, he says that law enforcement has a clear class dimension, where “poor people get the stick and rich people get ushered into places.” But he is critical of how demands have been made. Both in his field journal and in his interviews, he highlights the difference between what he terms upper-class, conservative mobilization and left-wing mobilization, describing the former as rational and orderly and the latter as “burning down the city.”

Middle-class identity

The traditional middle classes fear not only the erosion of economic privilege but also contact with the other (Lawler Reference Lawler2005). Members recognize that poverty should be combatted but do not want this to affect their way of life. Urban space is highly segregated, with the traditional middle classes and elites considering it their right to live, work, and play in reserved territories. Their single-family homes, high-rise condominiums, schools, and sporting clubs hide behind walls to shut out those who do not belong, and the shopping districts and restaurants they frequent are all formally or informally exclusive. Poverty, inequality, and insecurity are concentrated in the inner city and peripheral territories that have inadequate schools, health-care facilities, public transportation and infrastructure, and leisure installations (Caldeira Reference Caldeira2000; field notes 2017, 2018, 2020). When the lower classes demand access to traditional middle-class space, the latter balk.

The citizenship rights of democratization, combined with the social and economic policies of the Lula governments and the commodities boom, empowered the vulnerable to access traditional middle-class spaces, but they have been met with prejudice. As the vulnerable asserted their presence, the middle classes tended toward “attitudes of non-negotiation” and a “generalized climate of fear,” criminalizing poverty and supporting police violence against perceived public danger (Holston Reference Holston2009, 261–262). Fear is a familiar trope in the media and politics and shapes the privileged Brazilian’s experience of the favela (Sul de Minas 2013; R7 2015). The traditional middle classes view favela residents as uncivilized and criminal and the newly nonpoor as “getting above themselves,” generating a sense of hostility (Anderson 2011; Saad-Filho and Boito Reference Saad-Filho and Boito2016).

The rolezinho is telling in its manifestation of a demand for access to the traditional middle-class space of consumption that is the shopping mall, and for the resulting backlash.Footnote 16 The first rolezinho occurred in São Paulo, in December 2013, and spread across the country, with each outing involving from dozens to thousands of (often black) youth. Youth from poor neighborhoods used social media to organize gatherings in malls, where they would hang out and sing funk songs with lyrics about having money and name-brand consumer products (Pereira Reference Pereira2014). The response to these “incursions” into privileged space was fear and violence (da Silva and da Silva Reference da Silva and da Silva2014). Mall and store doors were locked, while private security and police—including special forces (Pereira Reference Pereira2014)—armed with tear gas and rubber bullets faced off against the kids, often deciding who could enter the malls on the basis of race (Assis Reference Assis2014). Businesses took the issue to court, attempting to gain legal support for barring access to their establishments (Severi and Sanchez Reference Severi and Sanchez Frizzarim2015).

Whether in their response to the rolezinhos or through explanations for the increasing walling in of their homes and spaces of leisure, consumption, and business (see Caldeira Reference Caldeira2000), the traditional middle classes identify reason and refined culture in manifesting their superiority to, and right to separateness from, the lower classes (O’Dougherty Reference O’Dougherty2002; Lawler Reference Lawler2005). “A good part of the middle-class experience seems to be immaterial, a state of mind” (O’Dougherty Reference O’Dougherty2002, e-book location 289) that binds its members together in an agreement that they are not like the poor and the vulnerable.

While Eduardo is not immune to the struggles of the lower classes or to the racism that suffuses service refusal and police violence, he does have strong ideas about how equality should be approached and about the value of class culture. He supports the civil rights and liberties embodied in the negative rights of legal protections guaranteeing every individual’s freedom to act, but not the positive rights of government policies supporting socioeconomic inclusion (see Berlin 2002). And he believes that, to share the spaces traditionally reserved for the middle classes, one has to know how to behave. This sentiment is widespread in the new right and often articulated more harshly than by Eduardo. The traditional middle classes that have mobilized as part of the new right fear the invasion of their working, living, and leisure spaces by the newly empowered poor, black, women, and LGBTQ+ (see Messenberg Reference Messenberg2017). Significant parts of the vulnerable class vote for politicians representing these fears, afraid of weakening their own newly acquired privileges through solidarity with the poor.

Conclusion

This accidental biographical ethnography has traced Eduardo’s history and sociopolitical perspectives with the aim of illustrating class tensions in Brazil. Using a combination of economic, sociological, and cultural factors to construct an understanding of the middle classes, we have argued that there is no “new middle class” but rather an expanded vulnerable class, and that the traditional middle classes are sometimes willing to support the lower classes’ demands for rights, as long as these do not encroach on middle-class privileges. These tensions have been a regular pattern across Brazilian history, challenging the assumption that democracy inevitably grows alongside middle-class expansion (see Rueschemeyer, Stephens, and Stephens Reference Rueschemeyer, Huber Stephens and Stephens1992; Chen and Lu Reference Chen and Lu2011).

Eduardo eventually felt so alienated and fearful of future economic insecurity that he decided to emigrate. He chose Canada as his destination and took two years to save for the immigration application, travel costs, and a couple of months of living expenses. He also applied to a university liberal arts program to study liberal thinkers. Unable to find work once in Canada, he lived in a “shitty” inner-city apartment and applied for a student loan. He eventually found a tutoring job that he held throughout his BA. Upon graduating, he was offered a fully funded position in an American PhD program but dropped out after a year, at odds with the faculty’s critical perspective on class relations. He is now working for the government of Canada and says, “I moved to Canada because I want my kids to live in affluence. Period.”

Acknowledgments

This article is a product of Concordia University’s Lab for Latin American and Caribbean Studies. We would like to thank Lab members and three anonymous reviewers for comments. The field journal prompting our reflections was part of a project generously funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.