No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

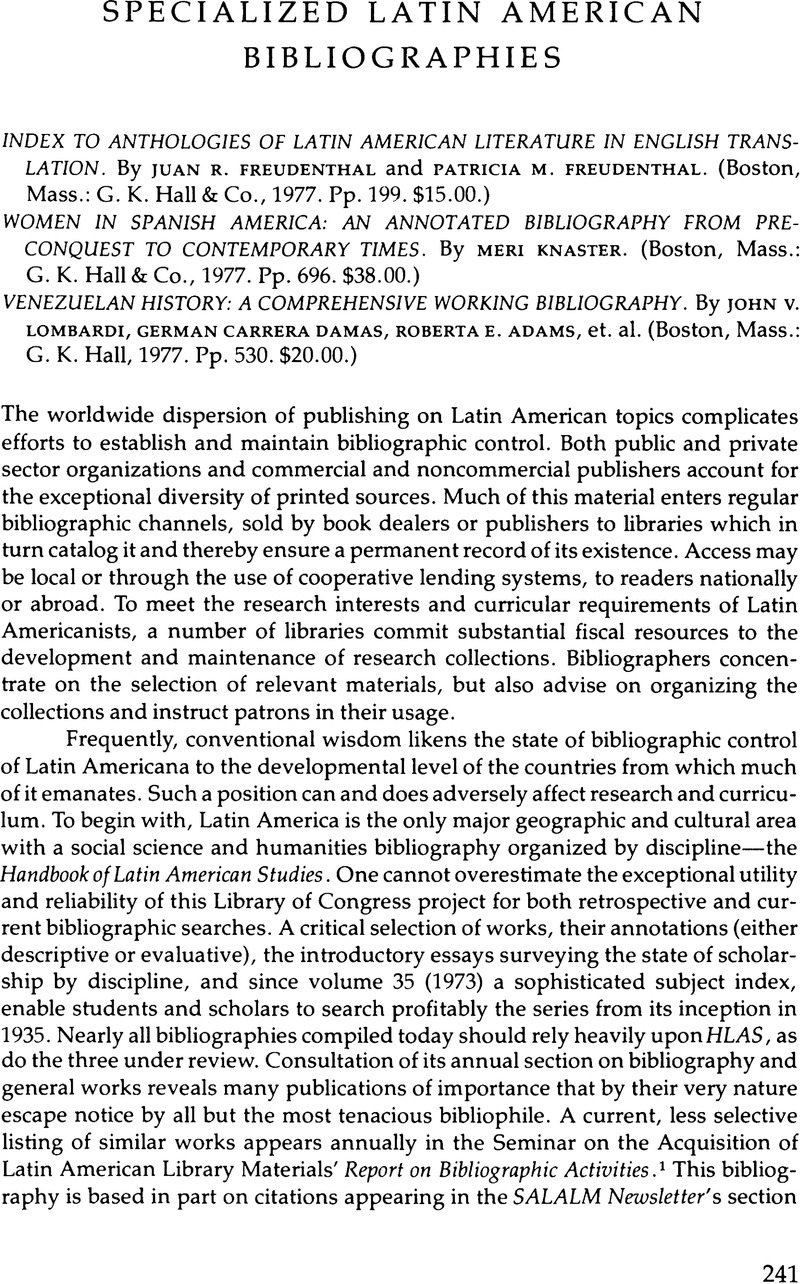

Specialized Latin American Bibliographies

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Books in Review

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1980 by Latin American Research Review

References

Notes

1. Issued as a preprint for the annual conference, it appears later in the published Final Report and Working Papers.

2. For French and Dutch anthologized authors see Bradley A. Shaw, Latin American Literature in Translation: An Annotated Bibliography (New York: New York University Press, 1976), which unfortunately does not identify individual works, just anthologized authors.

3. The Essay and General Literature Index (New York: H. W. Wilson Co., 1934–) covers annually since 1900 anthologized writings.

4. Claude L. Hulet, comp., Latin American Poetry in English Translation: A Bibliography (Washington, D.C.: Pan American Union, 1965) and for drama, essay, and the novel see his Latin American Prose in English Translation: A Bibliography (Washington, D.C.: Pan American Union, 1964).

5. This can be risky; see Jean R. Longland, “World World Vast World of Poetic Translation,” Latin American Research Review 12, no. 1(1977):67–86, for the joys and pitfalls of translating literature.

6. The Freudenthals endeavor to provide birth and death dates when known. For some authors nothing appears although the information is available (e.g., José de Jesús Esteves, 1882–1918, and Armando Tejada Gómez, 1929–); for others errors exist (e.g., Demetrio Aguilera Malta, 1909 not 1905, and Bernardo Canal Feijóo, 1897, not 1898). In the country index (p. 185) Olavo Bilac (entry 132) appears with Bolivian authors rather than Brazilian. Engber's Caribbean Fiction and Poetry (p. 193) has 427 items, not 472.

7. Given the fact that unlike English language journals most Venezuelan ones receive limited indexing, the decision to exclude important scholarly work because of physical format seems most unfortunate.

8. E.g., Spain. Sovereigns. Documentos para la historia colonial de los Andes venezuelanos; siglos XVI al XVIII, Caracas, UCV, 1957. 317p.

9. Most works in this category involve the compiler and editor as author, rather than corporate authorship. Users should use the title approach to locate these items in library card catalogs. See for example item 887, “Enrique Otte, comp.,” which under nationally accepted rules is “Spain. Sovereigns, etc. 1516–1556 (Charles I).”

10. See the dictionary catalogs published by G. K. Hall for collections of Texas-Austin, Florida, New York Public Library, Oliveira Lima Library, Miami, Bancroft, and Tulane; Harvard publishes their own as part of the Widener Library Shelflist series.

11. Indeed, Knaster credits the foundation of her work to the bibliography course taught by James Breedlove at Stanford University, (p. xxii).

12. See “Guidelines for Bibliographic Instruction in Academic Libraries,” College and Research Libraries News, No. 4 (April 1977), p. 92. These became policy for the Association of College and Research Libraries 31 January 1977.