Exorcismos de esti(l)o (1976) is probably the least known book by Guillermo Cabrera Infante; it is not only little read but also little studied by critics because of its complex and challenging nature. Indeed, until a few years ago, researchers had been obsessively focused on Tres tristes tigres (1967) and, secondarily, on La Habana para un infante difunto (1979). In the past ten years, however, critics have tried to broaden their scope, although Cabrera’s first novel continues to enjoy most of the attention. A few researchers have focused on his other books. These include Omar Granados (Reference Granados2012), Iván Eusebio Aguirre Darancou (Reference Darancou and Eusebio2014), and David Saldaña (Reference Saldaña2021), who have studied his posthumous work; Javier Fernández Díaz (Reference Fernández Díaz2016), who works to provide new hypotheses about Cabrera’s role as a scriptwriter and a film critic; and Alessandra Ghezzani (Reference Ghezzani2015), who elaborates a novel approach to Vista del amanecer en el trópico (1974). Claudia Hammerschmidt (Reference Hammerschmidt2017) published, together with a group of researchers, a volume with explicit claims of going beyond the never-ending study of Tres tristes tigres, but it is surprising that even in this compendium the space dedicated to Exorcismos de esti(l)o, which absolutely needs to be studied, remains very limited. Very few researchers have dared to analyze this work, although it is fundamental to an understanding of Cabrera’s poetics. Therefore, the contributions of Andrés Ortega Garrido (Reference Garrido2015), who analyzes the classical materials in Exorcismos de esti(l)o, and Mercedes Kutasy (Reference Kutasy2016), who describes the game initiated by Cabrera as a reflexive exercise on linguistic and conceptual variations, deserve recognition.

The complex content of this work, which is also designed in a highly atypical format, is a challenge for the reader. It is a miscellany made up of vignettes, short stories, minifictions, anecdotes, descriptions, reflections in the form of notes, drama scenes, word lists, letters, visual texts, essays, suggested exercises for the reader, monologues, dialogues, poems, and informative texts, some with scientific claims, definitions, texts consisting of a single sentence, and some others built on the basis of questions, etymological explanations and journalistic columns, science talks, transcriptions of oral texts, and examples of rhetorical figures, among many other formats. Although this book shows an accumulation of proposed genres and styles, Cabrera’s usual poetics of excess, that verbiage that we find in almost all his work, is not part of this volume. Here, each written production relies on the exact amount of words needed. They are condensed, precise texts that silence more than they say and that, due to the intensity of their content, have intimidated researchers. Making explicit what is implicit in this book is the purpose of this article.

The weight of history

Almost all the texts that make up Exorcismos de esti(l)o were written between 1962 and 1965, years in which Cabrera Infante was hired as a cultural attaché in Brussels (Paris Review 1996, 71). However, it is relevant to note that, as Cabrera himself states, the book was completed a few years later, around 1970 (García Reference García2002, 227), that is, when he no longer had the option of returning to his homeland and remained in exile in the United Kingdom. The date and circumstance of the texts are essential to understand the essence of the book. Let’s look, first, at the events that led Cabrera to work in Belgium.

Cabrera’s ideology, opposed to Fulgencio Batista’s regime, led him to become one of the intellectuals who fervently supported the Revolution. His intellectual involvement in the revolutionary movement—recounted in Cuerpos divinos (2010)—allowed him to direct the supplement to the magazine Revolución called “Lunes de Revolución,” to which a television program was also associated.Footnote 1 Cabrera’s brother, Sabá, along with Orlando Jiménez Leal, made a documentary about Havana nightlife with the intention of showing it on the supplement’s television program. The broadcast, however, was banned by the regime for allegedly immoral content. This triggered the incomprehension and discomfort of the intellectuals gathered around “Lunes de Revolución.” The weekly, an open space for debate and reflection, was closed on November 6, 1961, by the regime to avoid creating further tensions.

Indeed, in June 1961, Fidel Castro had made explicit the obligation to take sides for or against Castroism in its entirety, without question: “dentro de la revolución, todo; contra la revolución, nada,” he decreed (Castro 1972, 363). For a personality like Cabrera’s, opposed to monolithic thinking and open to reflection and constant self-criticism, perplexity was high, as were disappointment and unease. As Cabrera’s discomfort became apparent, in 1962 he was offered the opportunity to work as cultural attaché to the Cuban embassy in Belgium or, in other words, “after the closure of ‘Lunes de Revolución’, a group of intellectuals problematic for the regime is ‘removed’ from Havana”Footnote 2 (Munné, in Cabrera Infante Reference Munné2013, 11 [translation mine]).

Although Cabrera’s concern for the lack of freedom of expression in Cuba accompanies him throughout the years he is in Brussels, only when he returns to Havana in 1965 with the death of his mother does he understand the real situation of the country. As can be read in the fictionalized autobiography Mapa dibujado por un espía (2013), the persecutions of intellectuals are already plain to see, the people are self-absorbed, as if they had accepted censorship and no longer remembered that promise of freedom offered by the Cuban Revolution. Years later, in 1968, Cabrera confesses:

Todavía en Bélgica yo añoraba Cuba, su paisaje, su clima, su gente, sentía nostalgias de las que no me libro aún, y pensaba nada más que en regresar. Pero un país es no solo geografía. Es también historia. […] En Cuba, la luna brillaba como antes de la Revolución, el sol era el mismo, la naturaleza prestaba a todo su vertiginosa belleza. La geografía era la misma, estaba viva, pero la historia había muerto. […] El socialismo teóricamente nacionaliza las riquezas. En Cuba, por una extraña perversión de la práctica, se había socializado la miseria (49).

On that trip to Castro’s Cuba in 1965, he understood that there was no turning back, that returning to his homeland was no longer an option for him. He became aware that to have free speech, it was necessary to detach himself from the country and go into exile. In fact, the prohibitions and cultural decadence that he becomes aware of when stationed in Brussels and experiences firsthand when he returns to Havana, are only the beginning of a sharp decline in freedom of expression, as can be seen in his declarations of 1969:

Se creó la atroz Unión de Escritores, se clausuró “Lunes de Revolución”, se hicieron sistemáticas las persecuciones a escritores y artistas por supuestas perversiones éticas (e.g. Por pederastia: presos Virgilio Piñera, José Triana, José Mario, destruido el grupo El Puente, Raúl Martínez echado de las escuelas de arte junto con decenas de alumnos ejemplares, allí y en las universidades, Arrufat destituido como director de la revista Casa, etc. etc.) cuando en realidad se les castigaba por desviaciones estéticas (i.e. Sabá Cabrera, Hugo Consuegra, Calvert Casey, GCI, exiliados; Walterio Carbonell, sociólogo y viejo marxista de raza negra, primero expulsado de la UNEAC por decir que en Cuba no había libertad de expresión y ahora condenado a dos años de trabajos forzados. (Cabrera Infante [1969] Reference Cabrera Infante and Munné2015, 485)

From the drowned word to the island of words

In December 1979 Cabrera lamented: “Exorcismos ha sido un libro mal comprendido. Se tomó como un lío literario mío más” (García Reference García2002, 230), a fact he still regretted in 1982, when he confessed to Alfred Mac Adam that it was one of his favorite books. Unfortunately, it had not been given the necessary attention, and he concluded that, of course, it could be described as “harina de otro costal” (Paris Review 1996, 71).Footnote 3 And that was true. The book holds a tremendous number of references to the isolation caused by the political situation in the country. Begun in distant Belgium as a consequence of Cuba’s progress toward censorship and completed a decade later in the pain of exile, Exorcismos de esti(l)o pushed the limits of language to become an exorcism of style.

Indeed, the miscellany that is Exorcismos de esti(l)o is not part of his novelas del yo, a term used by Manuel Alberca (Reference Alberca2007, 60) to refer to novels that “establecen una dialéctica y tensa ecuación entre lo ficticio y lo vivido, entre lo real y su simulacro. Cada una de ellas representa una manera particular de metabolizar la experiencia propia y ajena en la escritura narrativa y de alumbrar el binomio vida-literatura.” In Exorcismos de esti(l)o, instead of walking his alter ego through the streets of Havana as in his numerous novelas del yo, Cabrera exercises his writing so as to appropriate signs, words, and styles to improve his technique and subsequently be able to obsessively, repeatedly rebuild a fictional Havana of words in his novelas del yo.Footnote 4 In other words, under the weight of censorship, of stifled freedom of expression, of the broken verb, Cabrera tries to take possession of the only tool left to him to approach a Havana that no longer exists; taking over the language, making it his own, giving life to the drowned word, he creates a city in which there is still hope for revolution, the Cuban capital as anchored in the years before Castroism.

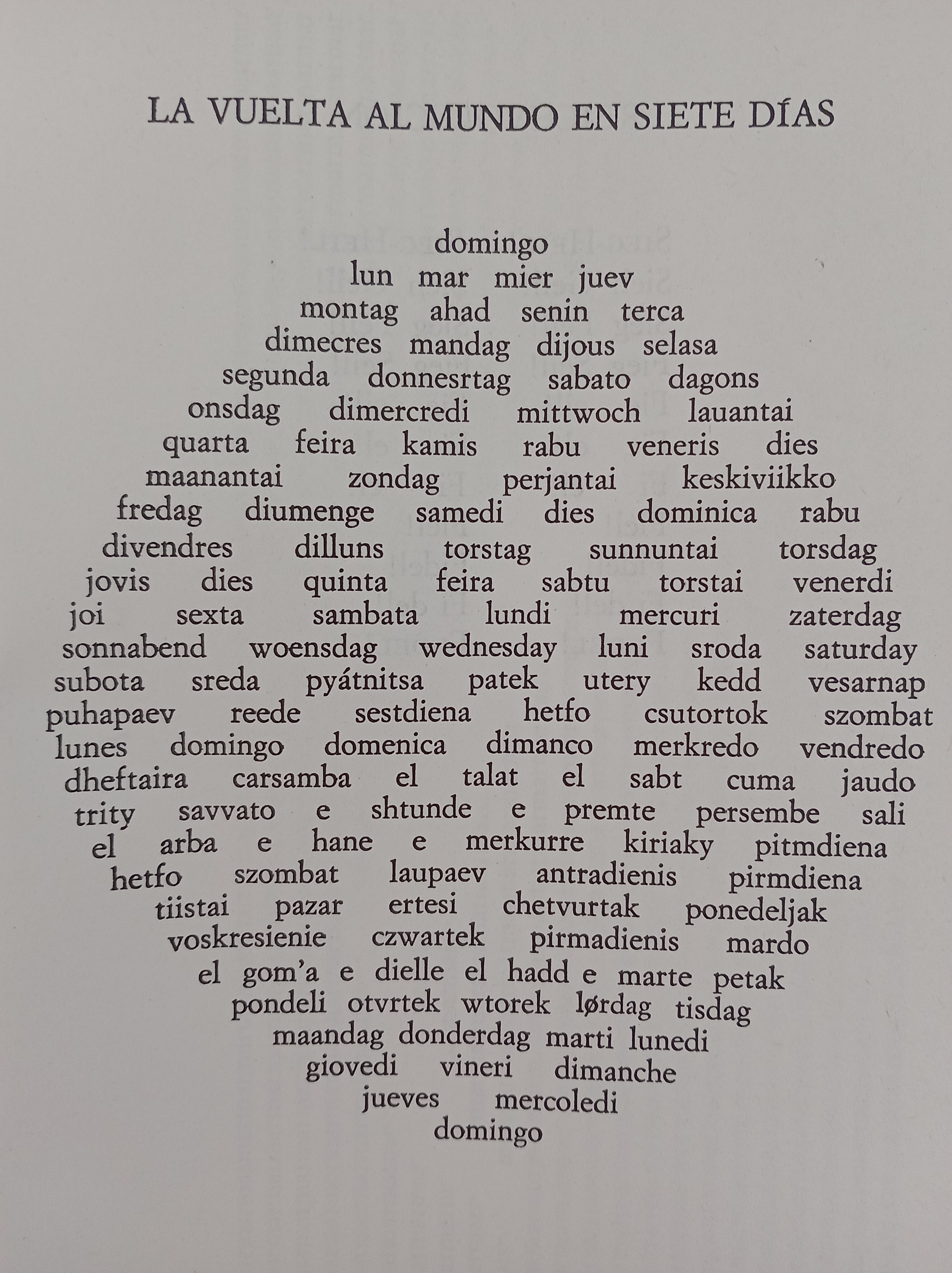

By putting language to the test throughout the book, Cabrera is able to build a world whose only material is words. For this reason, at the end of the miscellany, more specifically on page 289, we find: the image of a world built with words [Figure 1]. The Cuban geography outweighed by history resurfaces from a sea of words—remember the words of the author in the interview mentioned previously. With censorship Cuba disappears, the possibility of recapturing it disappears, historical reality has swallowed it up, only the word can resurrect it, restore its silhouette, and give it life in each of Cabrera’s novelas del yo.

Figure 1. La vuelta al mundo en siete días, 289.

In Figure 2, note how the repetition of the word mar (sea) contains arma (weapon), since writing is the weapon that allows Cabrera to recover the lost land. He tries to capture the language, to exercise the language so as not to become speechless, and, therefore, retain the ability to reinvent the island, not because the country is geographically far from Europe, but because history has consumed it. In fact, in the last years of Cabrera’s life, when Castroism had lost its fierce strength, he could have returned to Cuba. However, he never planned it, as the free Havana that he had yearned for, before and during the revolution, was irretrievable. Returning would not have given him satisfaction—quite the contrary. In this regard, Ángel Esteban (Reference Esteban2008, 45) comments: “Estoy seguro de que Guillermo Cabrera Infante no se habría atrevido tan fácilmente a volver a su ciudad, la de las columnas, aunque el dictador hubiera muerto antes que él. La muerte de una ciudad, ahora en ruinas, a la que se le notan las arrugas y el deterioro, quizá hubiera sido letal para él. La Habana nunca será la misma de los años cincuenta.”

Figure 2. Exorcismos de esti(l)o, 291.

As a geographical return to Havana would not mean recovering its essence, Cabrera needs to modify the space and time of real Havana, needs to use his imagination to bring it closer to London, in order to immerse himself in it and anchor it in the hopeful time before Castroism. To do this, he turns to games, which have their own spatiotemporal coordinates. Indeed, once players have accepted the rules of a game, they immerse themselves in it and assume that the game itself imposes its own time and space, so that the players’ own time and space are suspended.Footnote 5

This ingenious challenge of time and space is made explicit in various excerpts from Exorcismos de esti(l)o. For example, in a heartbreaking text, “Tragicomedia en el centro del laberinto” (1976, 75–84), the reader experiences the emotions of the Minotaur who, trapped in the labyrinth, expresses in his interior monologue his illusions, hopes, and joy, as well as his worries, disappointments, and sadness. At a certain point in the story, the Minotaur remembers a conversation he had had with Daedalus. As the architect explained, the labyrinth is a machine with which the Minotaur will be able to reinvent his space:

Luego me halagó, me alabó, me acabó diciéndome que yo era el único en el mundo y tal vez en el universo que podía disponer de dos máquinas dimensionales, una para medir el tiempo y otra para medir el espacio, y hacerlas mi habitación. Dijo que esta construcción concéntrica, esta máquina espacio-tiempo, este doble reloj de las horas y los pasos, era única en el universo y que yo, afortunado, estaba exactamente en su centro, era ese centro. El Centro. Bromeando agregó: ¡Eres un minotauro central, el Centrauro! (77)

It is with these words that Daedalus triggers euphoria in the Minotaur, who now believes that he has the power to make that labyrinthine space a home by choosing his own space-time. But in the next paragraph he must face the facts and see how terrible his situation is—“Entre bufidos no pude darme cuenta de que iban echando sobre mí el techo sin ruido” (77)—and he remembers Daedalus’s terrible words: “Pero para ti, me dijo, sólo queda ya la noche” (77), and he laments: “Y era verdad. Era de noche, únicamente noche y todo noche, bajo techo.” This highly symbolic text expresses all the pain of the exiled author. In effect, Cabrera applies the spatial-temporal coordinates of the game to Havana, thus challenging reality and building an island of words, over and over again, as if he were a demiurge; however, it is not a light task but a painful exercise in survival.

In 1979 Cabrera explains in what mental condition he finished writing Exorcismos de esti(l)o: “desde mi nervous breakdown (léase locura), me siento religiosamente cada tarde […] y trato de escribir por lo menos mil palabras (quita cien o pon cien más). No es más que mera terapia mental: es la única forma de alejar la depresión que me ronda” (García Reference García2002, 205). For this reason, in “Levantarse para caer enseguida” (27–28), Cabrera makes a literary text out of the need to write in order to drive away the ghosts of exile that haunt him. He takes control of the situation by practicing the writing style until he captures and possesses it; in such a way that he will be able to create a fictional Havana of words in his novelas del yo. After recounting how hard it is for him to get out of bed, he adds: “Pero como hay que levantarse a vivir, as the show must go on, la única alternativa es buscar el sueño por otros medios en el suicidio. Tomar ese revólver (imaginado) y levantarse limpiamente (es un decir, claro) la tapa de los sexos. O dejarse hecho tortilla cayendo de lo más alto de la torre de marfil, de perfil. O colgarse espasmódicamente de un árbol, como un fruto carnoso pero con demasiadas semillas” (27). He concludes: “en vez de suicidarse, sentarse a la máquina de bordar bellas palabras” (27–28).

The persecuted

Although the self-exiled Cabrera was able to talk freely, he lived in constant fear of persecution. In 1968 he confessed that since settling down in London, regular events had occurred that reminded him of the hostility with which his country treated him: “calumnias personales y políticas, negación del permiso para trabajar en la Unesco, confiscación de libros enviados por correos, minuciosa inspección de la correspondencia familiar y deliberada persecución literaria” (48). The slanders were not only direct, but the regime censored all those intellectuals who wanted to praise his work in public:

A un novelista europeo se le invita en La Habana a un panel televisado sobre literatura cubana, con el compromiso expreso de que no mencione mi nombre. El huésped es bien educado y cumple su palabra, pero con lealtad personal y honestidad ejemplares (o suicida, en el mundo comunista) habla de Tres tristes tigres. Olga Andreu, bibliotecaria, pone mi novela en una lista de libros recomendados por esa democrática biblioteca de la Casa de las Américas, boletín que ella dirige, y a los pocos días es separada del cargo y condenada a una lista de excedentes, lo que significa un terrible futuro porque no podrá trabajar más en cargos administrativos y su única salida es solicitar ir de “voluntaria” a hacer labores agrícolas. Heberto Padilla escribe un elogio a Tres tristes tigres y, con un golpe de dedos que no abolirá al zar, da comienzo a la polémica mencionada. (48)

Although these persecutions became palpable only once in exile, he was already being ostracized before, as the supplement in which Cabrera worked was canceled, and the regime forced him to go to Belgium to continue working in the field of culture. It is not surprising, therefore, that symbolic historical figures should make an appearance in Exorcismos de esti(l)o. Many of them were persecuted for championing ideas or actions that conflicted with the ideals of others in power and most were betrayed by their own people.

For example, “La tumba del creyente no creído” (137–138) tells the story of Korpik, the German worker who wanted to prevent the Nazi invasion of Russia and came to this country to warn the Russians about the German attack plan. The story tells that Stalin did not believe him, and he was accused of lying and spreading panic, “queda arrestado en el acto, acusado de ser un agente nazi, juzgado sumariamente por un tribunal militar, condenado a muerte (sin apelación) y fusilado sur le champ. Korpik, viejo comunista, muere como un noble traidor: con dos tiros de pistola en la nuca, después de haber sido obligado a cavar su tumba.” He concludes: “ese creyente destruido por los defensores de su propia fe” (137). Like Korpik, those who persecuted Cabrera were those whom he had supported: after the hopeful revolution, the long-awaited new regime, holding the promise of emancipation, followed, a regime in which Cabrera played an important intellectual role. If lack of freedom under Batista was an established fact, he had a hard time accepting a situation in which censorship was imposed by his own people.

Another character persecuted by his own people was the cartographer Mercator: “aunque decía profesar la fe que detentaba el poder entonces, sufrió persecuciones religiosas, y al ser acusado de hereje se vio obligado a dejar Flandes para ir a vivir en la Alemania protestante” (130), as Cabrera mentions in “Las misteriosas proyecciones de Mercator” (130–134). According to him, ingenuity is the only tool left to the persecuted to survive. Referring to Mercator, Cabrera subscribes to those words of James Joyce:

Aparece en el epitafio del panegirista anónimo que lo calificó de ingenio dexter, dexter et ipse manu –“astuto y diestro, de mente como de mano”. Esta cualidad oculta es la coraza ofensiva de los perseguidos, del exilio– todavía lo es. “Silence, exile, cunning”, recomendará al artista exilado cuatro siglos más tarde otro cartógrafo del doble laberinto humano y urbano.” (134)

It is ingenuity, along with appropriation and playful use of language as a response to James Joyce’s “Silence, exile, cunning,” that will save Cabrera from ostracism. He also identifies with Mercator in his role as cartographer: “¿Es una casualidad que la Orbis imago sean dos cartas geográficas enfrentadas para formar un corazón?” (130). This same love for a geography anchored in time recurs repeatedly in his novelas del yo.

“Un filósofo feliz” (125–128) tells the story of another persecuted man, Jean-Anthelme Billat-Savarin, “a quien salvó de la guillotina su amor por la música, del Terror su astuto exilio en América y de la mortalidad del espíritu por la inmortalidad de la letra su Physiologie du goût.” In this text, Cabrera takes the opportunity to implicitly highlight Castro’s bad eating habits, which are later made explicit in Cuerpos divinos (2010). In Exorcimos de esti(l)o we read:

Los déspotas tienen invariablemente el gusto enfermo. Napoleón, el mismo Brillat-Savarin lo cuenta en su libro, comía poco, mal y sin concierto. Hitler era vegetariano. Stalin inundaba sus toscas comidas con vodka. El único tirano, cuyo nombre no quiero (ni puedo) anotar, con quien tuve el disgusto de compartir varias comidas, tenía, entre otros, el hábito de mezclar –¡con una cuchara, por favor!– el arroz, los frijoles negros, un picadillo a la criolla y los deliciosos plátanos fritos en un asqueante tojunto que un cerdo habría rechazado por promiscuo. (127)

That being said, the texts are not only dedicated to persecuted characters; they also refer to all those wonders that, throughout human history, have been banned, burned, or destroyed, such as the library of Alexandria, the comedies of Menander, the poems of Sappho, all the texts listed in the index Librorum Prohibitorum, the manuscripts of Bruno Schulz burned by SS officers in the Drohobycz ghetto, and so on, but also the cathedrals, libraries, and museums destroyed by world wars, among many other examples of persecuted art and thought (141–142).

Silence or echo

When Cabrera returns to Cuba in 1965 and comes face-to-face with what his beloved city of Havana has become, he feels that there is something false and artificial in that vision, as if it were a modified reflection of his old Havana. As he confessed in 1968: “Cuba ya no era Cuba. Era otra cosa –el doble del espejo, su doppelgänger, un robot al que un accidente del proceso había provocado una mutación, un cambio genético, un trueque de cromosomas” (49). For this reason, in Exorcismos de esti(l)o, the attempt to represent estrangement, reflection, echo and other forms of double is constant; so is the attempt to represent confinement and the desire for freedom, the dichotomies of inclusion-exclusion and inside-outside. It is therefore not surprising that, in the unifying thread of the miscellany, in which the political reality of Cuba cannot be made explicit, Echo appears as a recurring character. Other highly symbolic mythological characters, such as Icarus, Daedalus, and the Minotaur, are also prominent, the latter even being the dedicatee of a whole section of the book entitled Minotauromaquia (67–84).

When the goddess Hera condemns the eloquent Echo to silence, she censors her speech but not her voice. If Echo wants to talk, she can use only other people’s words. Translating this idea to the reality of Cuba in the 1960s and 1970s: without freedom of expression, Cuban intellectuals were forced to keep silent to avoid persecution; if they wanted to speak, they could only repeat the regime’s speech, as Castro himself proclaimed in the 1961 decree previously mentioned.

Furthermore, it is plausible that the fervent hope of the Cuban people with the revolution is represented in Exorcismos de esti(l)o by the image of Icarus. Icarus gets so close to the sun—that is, he puts so much wish and hope into his flight out of the labyrinth, in his search of freedom—that his wings melt and he falls into the sea “en una zambullida desastrosa” (118), as Cabrera writes when describing Brueghel the Elder’s painting Landscape with the Fall of Icarus (La caída de Ícaro) in “Dos museos belgas” (116–119); and he adds: “Nadie sabe que acaba de ocurrir un desastre, más que histórico, eterno porque pertenece a la memoria humana, al mito, y volverá a ocurrir una y otra vez” (118). As indicated in “Cancrine” (25–26), once the hope of the revolution is extinguished, Havana is left without “Ícaro, Ala ni Vida” (26). In a similar vein, the plants in the story “El suicidio de los helechos” (232–233) also seek to free themselves from the rope that currently holds and immobilizes them, which is purposefully red. To that end, they jump out the window, but they fall into the void and die. The search for freedom, once again, is thwarted and the narrator wonders, “¿Será el helecho una encarnación vegetal enraizada de Ícaro?” (233). Here, the words in the description of Brueghel’s painting become particularly relevant: disaster will happen over and over again—the will to free oneself from oppression leads to exhilaration and ultimately to one’s downfall. This same idea of the betrayed illusion is witnessed in the despair of the Minotaur who, in “Tragicomedia en el centro del laberinto,” is moved as he sees his sister Ariadne arriving and thinks that she is coming to save him from the labyrinthine confinement. After the highest emotion, he discovers the hostility of her attitude and its terrible outcome. Over and over again, the texts of Exorcismos de esti(l)o re-create the illusion of the revolution and the disillusionment produced by the revolutionary regime’s act of betrayal.

As far as the need to be silent is concerned, the text “Autorretracto” (21–23), which opens the first section of the book “Textos contextos” (19–52), sets out to be a self-portrait (autorretrato), with the particularity that, by adding an unexpected c to the Spanish word, the concept of retracting blends with the idea of the self-portrait (autorretracto). Indeed, although the reader expects a portrait of the author, the text begins by purposefully discussing the meanings of the word punto, the punctuation mark that signals the end of a statement, the limit (period). In addition, throughout the essay, intrusive punctuation marks are added, making it difficult to read. In an ingenious way, Cabrera Infante dissects the constituent parts of writing a self-portrait, with a view to saying things that others would not say and to framing his self-portrait differently than the way writers are normally supposed to do. In short, the portrait in question arrives late and is truncated; only some physical features of Cabrera are mentioned. They are all that the author can mention of himself, since he must retract any statement of the ideas and feelings that also define him.

However, there are many texts that try to capture the strangeness of the image reflected in the mirror. In the description of the physical appearance of the author in “Autorretracto” (21–23), we find “pelo lacio largo y negro otrora que ya comienza a hacerse escaso a la izquierda de la vida y a la derecha del espejo” (22). Likewise, in Exorcismos de esti(l)o we notice numerous palindromes that reproduce the mirror effect, that is, the same inverted image, with that feeling of falsehood which Cabrera identified in the Havana of 1965. An example of this is the very short “Palindrama” (46): “Nada, yo soy Adán” and the complex “Cancrine” (25–26), which contains a dialogue between Adam, Eve, and a crab; the crab’s intervention is the axis that allows the mirrorlike inversion of the speech:

Regarding the falsity of the representation in this text, Kutasy (Reference Kutasy2016, 134) emphasizes: “en la creación de la ilusión tiene un papel relevante también el hecho de presentar a los protagonistas como si jugaran papeles, como si fueran actores que representan a Adán y a Eva en vez de ser Adán y Eva. Esto se logra añadiendo un indicador de tiempo que sugiere fugacidad, mutabilidad en el estado de los actantes: ‘Adán ve a Eva, que es ahora una poetisa hermética.’” Footnote 6

In turn, “Dédalo visto desde el Minotauro” (74) is an alphabet soup in which there is a central cross that can be seen as a double mirror: from left to right, from top to bottom, and vice versa. These visual reflections are also completed with echoic verses that, as their name indicates, allow forming a new word with a different meaning from the last transcribed sounds, as in the text “Consecuencias del amor de Narciso por Eco” (47):

Cabrera even talks about another type of echo, olfactory this time, in the text “Acerca del eco” (97): “Se acepta, generalmente, que el eco es la repetición de un sonido, por reflexión de las ondas sonoras. […] Como quien dice, un espejo sonoro. […] [P]ero, me pregunto, ¿se ha preguntado alguien más si es posible hablar de un eco oloroso? Muchas veces, la fuente de un aroma –o más corrientemente, de un hedor– se localiza lejos de sus efectos.” In short, Cabrera talks about echoes, reflections, censorship, and the impossibility of expression. Also, as we will see, he digresses about his struggles with representation.

Threats to representation

In his determination to re-create Havana with words, to sketch it with words, he needs to decompose language so as to observe and study its constituents to take possession of them, to personalize their meaning. Likewise, albeit in reference to the poetic genre, Kutasy (Reference Kutasy2016, 113–114) analyzes the texts that reflect on the value of language and its usefulness or uselessness as a vehicle for thought: “la expresión poética acertada no sólo se halla en las palabras que faltan, sino [que] causan igual dificultad las palabras que existen, básicamente por la cantidad de significados amontonados y petrificados en ellas. La única solución, por tanto, podrá ser si se emigra de la lengua a la materia de la misma, otorgando un significado único e individual a cada palabra, cuyo código ya no es uniforme sino depende de la obra poética concreta particular.” In line with this aim, numerous texts of Exorcismos de esti(l)o start from the minimum units of language. The most extreme text is “Poema semiótico” (281), where Cabrera even examines punctuation marks—mute elements of the language—as significant units. In principle, they only serve to contribute to the correct reading of the text.

However, Cabrera’s project fails to be completed, as searching for the essence of language is not enough to paint a picture of Havana; that is, between the thought and its reflection or the thought and its representation there is an enduring space. Cabrera does not want the illusion of the reflection, the mirage of Havana 1965. What he does want is to be able to portray the hopeful Havana of before the revolution. Worries about representation recur throughout Exorcismos de esti(l)o. In fact, the already-mentioned title “Autorretracto” also contains the word tracto (tract), that is, a space between two places but also a lapse of time, according to the dictionary of the Real Academia Española. If a self-portrait has the function of imitating or describing the image of the author, here Cabrera highlights the fact that representation is impossible, because it mediates between author and written expression, a tract.

That being said, in an attempt to overcome the difficulty of representation, Cabrera insists on drawing a picture of Havana through language. As he not only seeks to describe it, but to draw it, he tries to transcend words, and resorts to visual language. In this exercise, he tries to capture the image of speech prosody and even that of silence. Thus, in the dialogue between Demosthenes, Thesis, and Antithesis from the text “Cena y escena” (157–162), Cabrera uses capital letters to represent how loudly Thesis has to speak because of Demosthenes’s deafness:

If today, in the age of social media, this iconic representation is commonly accepted, that was not the case at the time. In fact, another text in the Exorcismos de esti(l)o combines upper- and lowercase letters, although, on this occasion, it is to represent the voice in motion. This text is “Neuma” (51), whose title announces the purpose of this alternation since, according to the DLE (2014), neuma is the “Declaración de lo que se siente o quiere, por medio de movimiento o señas, como cuando se inclina la cabeza para conceder, o se mueve de uno a otro lado para negar, o bien por medio de una interjección o de voces de sentido imperfecto.” The text consists of a single sentence: “nO tiREn pIeDraS ay MujeRES Y niÑOS” (51). The upper- and lowercase alternation can be understood as depicting the movement of a person dodging the stones that are thrown at him. That is to say, capital letters represent the sounds produced while standing and directly addressing the listener whereas the small letters capture the tenuous voice of those who, in trying to protect themselves, duck and cannot project their voice toward the listener. It is a transcription of a spoken text, so Cabrera does not use the unpronounced h of the verb haber. Furthermore, without the h, the verb becomes an interjection, representing the pain of the speaker who has not been able to avoid the stone.

In other cases, Cabrera tries to represent movement through visual language, as, for example, in “Tragicomedia en el centro del laberinto” and the alphabet soup that accompanies it, “Dédalo visto desde el minotauro” (74). About the first one, László Scholz (Reference Scholz2002) said, “Con unos recursos tan simples como la repetición, la inversión, la paronomasia, la rima interior, el autor crea, con sus propias palabras, unos zigzagueos que naturalmente están en concordancia con el hecho de estar perdido en un laberinto” (132). The Minotaur himself explicitly mentions Daedalus’s instability when walking: “Iba de lado Dédalo, haciendo eses, a juzgar por su cabeza, que era lo que yo veía. ¿Estaría ebrio o es que siempre caminó así y solamente me doy cuenta ahora?” (75). The Minotaur also plays with the palindrome that recalls the inverted echo: “¡O Daedalos, so ladeado! Grito y no me oye. Nadie me oye. Nadie por tanto me responde. Grito y el eco me devuelve el mismo grito al revés ¡odaedal os, soladeaD O!” (75). If the reader follows the Minotaur’s indication, according to which the architect was haciendo eses (zigzagging), and looks for the boxes that contain that letter in the alphabet soup of the adjoining page and joins them, he will observe the visual representation of the zigzagging movement ((see Figure 3):

Figure 3. Exorcismos de esti(l)o, 74.

In the same way, Cabrera tries to draw silence. In “Ocurrió en la ciudad de Al-khamuz” (215–216), for example, as the protagonist recounts what the female character said to him, when mentioning that the words came after a silence, their representation on paper follows a blank space (215). In the same way, the silence that is made in the narrator’s mind when he stops listening to his lover is represented graphically as if she stopped talking, that is, by breaking off the sentence with a blank space:

At other times, the graphical symbol itself is the symbol of the object represented. For instance, the text “Paréntesis como fosas ansiosas” (248) starts like this: “Como un obseso busco en los diccionarios las fechas de nacimiento y muerte de escritores famosos y a veces saco varias veces la cuenta de los años que vivieron” (248). From this point forward, the reader observes a list of author’s names, with their respective dates of birth and death indicated within paratheses. But at some point, the image of the graphic element that draws the parenthesis of the authors that are still alive takes on a different symbolism: “me lleva a pensar en el doble paréntesis que es como el borde de una fosa y en la primera cifra que espera, golosa, la llegada cierta de la fecha final y en el guión que es un trampolín, la barra de la muerte” (248). This twist in the text—the parentheses referred to calling to mind the picture of a grave—separates it from its initial lightness. As an embodiment of Cabrera’s attempt at visual representation, at practicing writing to be able to draw his beloved Havana, it is not surprising that Exorcismos de esti(l)o has an entire section in which ideas are represented by the texture of letters and words. The section is titled “CARMEN FIGURANTA” (269–291).

From the threat to the assumed mirage

That said, a great variety of texts from Exorcismos de esti(l)o talk about the impossibility of representation because, deep down, no matter how much effort Cabrera makes, a reflection is nothing more than a mirage of the real, just as the Havana that he draws with words in his novelas del yo is an echo of his Havana. For this reason, we find texts such as “La Habanera tú” (41–42), a dialogue between two girls who meet on the street in which we simultaneously observe what they express and what they think, emphasizing the hypocrisy of language, since thought and expression are not a faithful reflection of each other, as would be expected. The falseness in the representation can also be a temporary factor, as observed in the text “Obras maestras desconocidas” (151–156), where the characters reflect on the feeling of déjà-vu as a reflection of something already lived and, by analogy, of déjà-entendu, a reflection of the acoustic, even subjecting these feelings to time inversion: one of the characters speaks of the composer Stravinsky, who, at the moment when the story is set, has not yet composed the work that will bring him fame: “Stravinski es un compositor ruso que se hará notar dentro de muy poco tiempo. En 1913, para ser exactos, cuando componga su Sacre du printemps. ¿Qué le parece eso como tema para una sensación de déjà-joué, también conocido como future [sic] composé?” (153).

If language is not always representative of thought, neither is handwriting—that is, the way in which each individual draws the graphic signs of the alphabet—representative of the individuality of each human being, as stated in “Maculoscopía” (144–147). In this text, Cabrera states that graphology, which works to find out the psychological traits of a human being via handwriting, is useless considering that humans learn to write and, therefore, it is an artifice: “¿qué cosa puede ser más lábil y sujeta a variantes, artificios y francas falsificaciones, más o menos disimuladas, o bien simuladas, que la letra, que no es función de la mano, al ser la escritura un aprendizaje o arte, virtud e industria?” (145). Additionally, he proposes, with his characteristic humor, to analyze the stains on shirt bottoms, more representative of the individual imprint of each human being: “la mácula es, por así decirlo, una escritura natural, cuyos símbolos aún no hemos aprendido a descifrar aunque sí a anotar” (145).

In his ramblings about the original and its reproduction, Cabrera stubbornly searches for the entity whose reflection is observed on paper. For example, the text “La voz detrás de la voz” (143) suggests that it is language that hides behind the writing tool—typewriter or pen—that transcribes all speech. But even with this point made clear, Cabrera wonders who is hiding behind language, since the reflection is a mirage, an echo:

¿Quién escribe?

¿Quién habla en un poema? ¿Quién narra en una novela? ¿Quién es ese yo de las autobiografías? ¿Quién cuenta un cuento? ¿Quiénes conversan en esa imaginada pieza de sólo tres paredes? ¿Qué voz, activa o pasiva, habla, narra, cuenta, charla, instruye –se deja ver escrita? ¿Quién es ese ventrílocuo oculto que habla en este mismo momento por mi boca –o más bien por mis dedos?

La pluma, por supuesto, a primera vista o de primera mano anoche. O la máquina de escribir ahora en la mañana. Una segunda mirada sonora, escuchar otra vez ese silencio nos revelará –a mí en este instante; a ti, lector, enseguida– que esa voz inaudita, ese escribano invisible es el lenguaje.

Pero la última duda es también la primera –¿de qué voz original es el lenguaje el eco? (143)

In the same line of thought, in “Inquisición” (174) he reflects on the echo of the letters with which he writes his texts, wondering about the original letter and its reproduction or the chain of representations that is generated from the original entity:

¿Cuál es la verdadera letra:

(a) la que aparece pintada sobre la tecla, horizontal;

(b) la letra invertida en la matriz;

(c) la letra impresa vertical con ayuda de la cinta, regenerándose positiva;

(d) la letra que copia el proceso de tecla, matriz y letra impresa en una publicación

(e) o esa letra que repitiéndose ordenada forma poco a poco una palabra, una oración, una frase, un párrafo, una página, un escrito, un libro: la letra de la lectura?

¿Cuál es la letra, la de la escritura o la de la lectura? Y si hubiera una tercera letra por medio, invisible, ¿sería ésta la letra? (174)

Language autonomy

In his efforts to dominate the language that will allow him to transcribe the lost Havana, and in his stubborn and drawn-out attempt to work on the visual resources that might enable him to draw the Cuban capital with words, Cabrera not only struggles with representation and the mirage that accompanies his mission but also feels that the language escapes him and rebels against him. In “Arbitrariedad de los signos” (251), which does not refer to the autonomy of the sign decreed by Saussure as one might expect, the reader finds a text in which signs are gradually and arbitrarily inserted; this makes reading difficult, as if the writer could not avoid their insertion. However, Cabrera becomes aware of the autonomy of language as a living entity, which makes it even more difficult to appropriate. Moreover, in the text “Cómo hablar una lengua muerta” (102–109), the stages in the development of a language are assimilated, from its beginnings until its extinction, to the phases of life, from birth until death:

[La lengua] había llegado a lo que podemos llamar, sin pecar de impropios, su pubertad; de aquí continuó en su crecimiento hasta alcanzar la adultez, luego la edad madura, la presenescencia, luego la senilidad, vejez o chochera, en que su decadencia manifestó una cierta tendencia a la pendencia contra la independencia; después, como todos sabemos, vino la postración, el estado de comas, los estertores y, finalmente, la muerte: natural pero no por ello menos dolorosa para las lenguas hijas, sobrinas nietas y sobrinonietas. Hay que precisar vagamente que la Difunta murió rodeada del cariño de los suyos, aparentemente. (102–103)

But not only is the language assimilated to a living being, so are the pages of the book, with their printed letters. In fact, “Página para ser quemada viva” (49–50) consists of a blank page with that same inscription, and on its back side we can find a series of guidelines describing how to burn the page. In point 4 of the instruction manual, it is emphasized that the letters on the page are alive, and they will complain about their pain when they are burned: “4. Haga ojos sordos a los ayes de la letra impresa” (50). In short, although Cabrera tries to take possession of language by breaking it down into its constituents and giving them a different value, his writing tool is not as pliable as he would like it to be, because in addition to the difficulties of representation, language itself turns out to be a living being.

This study has highlighted the essence and purpose of a book that has been poorly understood by critics—as noted by its own author—and very rarely reviewed due to its complexity. It has been shown how, in the context of censorship, Cabrera exercises his writing to appropriate the constitutive components of language to build his defensive tool. This playful use of language allows him to challenge the real space-time coordinates and, thus, to re-create Havana over and over again in his novelas del yo.

I have argued that Cabrera summons up persecuted historical and mythological figures whose symbolic features indirectly allow him to talk about the reality of Cuba and, by extension, about his own reality. I have highlighted Cabrera’s recourse to a variety of literary forms to stage stories of defeated hopes, through which he echoes the revolutionary regime’s betrayal of the ideals of the revolution. In a fated attempt to draw a picture of hopeful prerevolutionary Havana, Cabrera uses scriptural strategies intended to help him navigate the pitfalls of representation. His mission, however, is doomed to failure. Whatever means he uses, he is forced to acknowledge that he is powerless to overcome the very essence of representation and the aliveness and autonomy of language.