The conventional wisdom in American politics posits that a political campaign is a learning process that helps voters support the candidate in line with their preexisting political dispositions. As a result of the campaign’s activation of voters’ political predispositions, people become “enlightened,” making election results largely predetermined (Reference Berelson, Lazarsfeld and McPheeBerelson, Lazarsfeld, and McPhee 1954; Reference Erikson and WlezienErikson and Wlezien 2012; Reference Gelman and KingGelman and King 1993). This is why the conventional wisdom is that campaigns have “minimal effects”; few voters change their declared candidate preference, and the few who do vote consistently with their precampaign political dispositions. In comparative politics there is a common assumption about the limited transportability of the minimal-effects model of campaign influence. Some literature on Latin American political behavior has argued that in young democracies, voters show little resistance to persuasive campaign messages (Reference Lawson and McCannLawson and McCann 2005; Reference Baker, Ames and RennóBaker, Ames, and Rennó 2006; Reference GreeneGreene 2011), because only a small minority of the electorate has partisan identities that are strong enough for them to be loyal to their preferred candidate. In fact, most studies have found at least a third of the electorate shifts its declared vote intention throughout the campaign, which represents a significantly higher proportion than in US elections.

This research, based on the Mexican case, contributes to the literature on campaigns by pointing out a different mechanism by which campaigns matter. This study argues that weakly formed partisan attachments make voters more vulnerable to campaigns.Footnote 1 Although most research has focused on the process by which partisanship develops in young democracies (e.g., Reference Brader and TuckerBrader and Tucker 2001, Reference Brader and Tucker2008) or the strength of voters’ partisan attachments in young party systems (e.g., Reference Lawson and McCannLawson and McCann 2005; Reference GreeneGreene 2011), this study focuses on a second dimension of partisanship overlooked by prior campaign studies: individual-level stability. Some voters in Mexico are able to build long-term partisan attachments, but other voters report short-term partisanship, which enables them to update their party identification as a campaign unfolds. This phenomenon is not limited to Mexican presidential elections or specific electoral cycles, but as this article shows, it persists in other Latin American party systems such as those of Brazil and Argentina. Moreover, these voters—short-term partisans—are more likely than long-term partisans to change the favorability of their copartisan candidate and shift their vote intention throughout political campaigns.

The findings have important implications for the campaigns literature, providing nuance to the understanding of how partisanship works in younger democracies like Mexico. First, although many party systems have the potential for voters to report unstable partisanship, voters may be more likely to update their partisanship during relatively short periods (e.g., campaigns) in young democracies like Latin America where party systems are less institutionalized and where voters have less political experience. In these contexts, voters who report short-term partisan attachments have a different behavior than long-term partisans. They have a harder time reinforcing their precampaign predispositions and report a disproportionate likelihood of changing their vote intention—adding a piece to the puzzle of why in Latin American presidential elections it is reported that a larger proportion of voters change their vote preference during campaigns than in advanced industrial democracies like the United States. Second, voters who have developed long-term partisanship and consistently self-identify with a political party between the beginning of the campaign and election day (the “true” partisans) are more immune to political campaigns than most of the comparative literature has assumed. They interpret new information so as to reinforce and report fairly similar electoral behavior as partisans in US elections: they have very stable vote choice throughout campaigns and report a strong connection between partisanship and the vote. These voters seem to rely on partisanship as the screen through which they observe the political world and suggest that partisans are not as persuadable as previous campaign studies suggest.

Partisanship and Party System Institutionalization in Young Democracies

Ever since original campaign studies in US politics, the literature on voting behavior has posited that campaigns play a major role in “enlightening” voters by providing information to bolster their support for the candidate most in line with their preexisting political predispositions (Reference Berelson, Lazarsfeld and McPheeBerelson, Lazarsfeld, and McPhee 1954), what the literature has called campaign “fundamentals” (e.g., partisanship, presidential approval, and evaluation of economy) (Reference Sides, Tesler and VavreckSides, Tesler, and Vavreck 2019). Voters’ partisan attachments, in particular, act as a strong filter of campaign information (Reference Lewis-Beck, Jacoby, Norpoth and WeisbergLewis-Beck et al. 2008); thus, voters reject information that is inconsistent with their political predispositions (Reference ZallerZaller 1992; Reference Gelman and KingGelman and King 1993), making them immune to candidates’ persuasive efforts.

In turn, the comparative literature on campaigns (Reference Lawson and McCannLawson and McCann 2005; Reference Baker, Ames and RennóBaker, Ames, and Rennó 2006; Reference GreeneGreene 2011) has noted that voters’ partisan identities do not seem strong enough for voters to be loyal to their preferred candidates. The present research, however, focuses on an alternative explanation. With few exceptions (Reference McCann and LawsonMcCann and Lawson 2003; Reference LupuLupu 2014; Reference Baker, Ames, Sokhey and RennóBaker et al. 2016) most comparative studies on campaign effects have focused on the development or strength of party identification in young democracies but have overlooked a key component of partisanship—individual-level stability, a measure of short-term partisanship—which has important implications for the campaigns literature. As explained in the following section, a pattern emerges in analysis of panel data from different Latin American presidential elections, which is not revealed with cross-sectional data: a significant proportion of partisans changed their party identification during the few months that the campaigns lasted.

Focusing on individual-level stability has several advantages. From a survey research perspective, instead of relying on a self-reported measure of partisan strength (e.g., when respondents self-report strong or weak identification with a political party), it analyzes voters’ responses to the party identification questions throughout the course of the campaign. This information allows for identification of those voters who have developed a long-term partisanship and those who have updated their party identification during the campaign period. Substantively, this means that for some voters, party identification does not constitute a perceptual lens for understanding the political world (e.g., Reference Converse and MarkusConverse and Markus 1979; Reference Jennings and MarkusJennings and Markus 1984), which allows voters at campaign time to reject information that is inconsistent with their precampaign predispositions. In turn, it appears that some voters have weakly formed partisan attachments, particularly those with less democratic experience. This short-term partisanship seems to constitute a “running tally” of political evaluations (Reference LupuLupu 2013) that voters update as the campaign unfolds, which is consistent with more rationalist interpretations of voting behavior (Reference FiorinaFiorina 1981). It is important to note that in many party systems voters can develop short-term partisanship—as has been found, for example, in electoral studies in Canada (Reference LeDuc, Clarke, Jenson and PammettLeDuc et al. 1984; Reference Clarke and StewartClarke and Stewart 1987)—however, voters may be more likely to update their partisanship during relatively short periods of time (e.g., campaigns) in young democracies like those in Latin America where party systems are less institutionalized, electoral competition is less stable, new parties tend to appear in each election cycle (Reference MainwaringMainwaring 2018), parties’ brands and reputations are weak (Reference LupuLupu 2014), and voters have less democratic experience.

From this perspective, political campaigns constitute a learning event that not only helps voters identify candidates’ positions, as in most advanced industrial democracies, but also helps voters to understand what the parties are and what they stand for. In other words, campaigns in young democracies are fundamental for voters’ political learning because during the campaign period, parties and candidates disclose political stances and structure voters’ political perceptions (Reference WeberWeber 2012). This is particularly important in party systems that have recently transitioned to democracy, where partisanship is necessarily limited by the country’s democratic experience and party labels and brands are still inchoate (Reference Lupu, Carlin, Singer and ZechmeisterLupu 2015). For those purposes, this article analyzes three specific ways that voters’ short-term partisanship can influence voting behavior during political campaigns: (1) partisan instability as a dependent variable, to identify individual-level factors associated with voters updating their party identification as the campaign unfolds; the influence of partisan instability on (2) voters’ candidate evaluations; (3) and vote choice. This first analysis will provide nuance about the types of shifts that voters experience during campaigns—updating their party identification to independent or crossing party lines—which are substantively different. Later, this study evaluates the effect of such types of partisan instability on voters’ behavior, in particular on candidate evaluations and stability of vote choice, which has been overlooked by most campaigns studies in Latin America. Both variables are conceptually different from partisanship, and voters’ partisan attachments are expected to act as an exogenous variable—because they are not defined in terms of voting behavior or evaluations—that affects respondents’ attitudes and electoral behavior.

Partisan Instability in Young Democracies

Most studies in US literature have found that partisan instability throughout political campaigns is a product of measurement error (Reference Green and PalmquistGreen and Palmquist 1990; Reference Green, Palmquist and SchicklerGreen et al. 2002). However, this study posits that in young democracies in Latin America, in which voters have less democratic experience (Reference Brader and TuckerBrader and Tucker 2001), voters have weakly formed partisan attachments that enable them to update their partisanship throughout the campaign, which makes them particularly vulnerable to political campaigns. In established democracies, as Converse (Reference Converse and Markus1979) argues, young voters inherit their initial partisan loyalties from their parents. Once individuals are eligible to vote, their experiences reinforce their early predispositions through the course of their life cycle (Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and StokesCampbell et al. 1960; Reference ConverseConverse 1976; Reference Jennings and MarkusJennings and Markus 1984; Reference Lewis-Beck, Jacoby, Norpoth and WeisbergLewis-Beck et al. 2008). However, in post-1978 democracies—part of the third wave of democratization—voters have a shorter democratic experience and less time to develop strong partisan attachments (Reference Mainwaring, Torcal, Katz and CrottyMainwaring and Torcal 2006).Footnote 2 This is what the literature has called the “acquisition of political experience,” the process of understanding what parties are and what they stand for (Reference McPhee, Ferguson, McPhee and GlaserMcPhee and Ferguson 1962; Reference Butler and StokesButler and Stokes 1975).

As Mainwaring (Reference Mainwaring2018) maintains, Latin American democracies are less institutionalized than advanced industrial democracies. When a party system is institutionalized, political actors behave in relatively stable and predictable ways and have clear and stable expectations about other actors: there is less uncertainty about how political actors behave, party brands have strong reputations, and electoral outcomes are more predictable.Footnote 3 In turn, in countries where new parties tend to appear in each electoral cycle and replace the old ones, most party labels are necessarily diffuse, and voters will not have a clear idea of what most parties stand for (Reference MainwaringMainwaring 2018). Even in contexts in which voters in young democracies can develop their partisanship as a product of early socialization—such as countries where political cleavages are rooted in predemocratic eras or democratic transition periods (Reference Greene, Sánchez-Talanquer and MainwaringGreene and Sánchez-Talanquer 2018)—partisan loyalties are necessarily limited by the survivability of political parties and the country’s democratic experience.

At the individual level, the lack of accumulation of political information and experience leads to weakly formed partisan attachments. As such, it is expected that voters who have self-identified for more years with a political party are more likely to report a stable partisanship over the course of the campaign, which will lead them to filter campaign information and reject information inconsistent with their political predispositions. On the contrary, those voters who have self-identified for a shorter period will be more likely to hold weakly formed partisan attachments, thus compelling them to update their party identification between the beginning of the campaign and election day. In light of this discussion, the first hypothesis focuses on the relationship between voters’ length of party identification and the likelihood of updating partisanship over the course of the campaign:

Hypothesis 1: Respondents who report more years identifying with a political party are less likely to update partisanship during campaigns.

This study also considers alternative hypotheses to explain voters’ partisan stability. First, as argued by American politics research, it is necessary to distinguish between substantive fluctuations and those that are driven by the survey instrument (Reference Green and StimsonGreen 1990; Reference Green and PalmquistGreen and Palmquist 1990, Reference Green and Palmquist1994; Reference Schickler, Green and FreemanSchickler and Green 1995). In other words, some fluctuations are a result of measurement error because imprecise survey research methods create the appearance of instability in party identification. Second, as in previous comparative studies, partisan instability can result from parties’ changing reputations (Reference Baker, Ames, Sokhey and RennóBaker et al. 2016). This is particularly important in studies that have analyzed the case of the Brazilian party system in which the Workers’ Party (PT in Portuguese) experienced changes that diluted the party’s brand. As a consequence, voters modified their perception of the party during the campaign and updated their partisanship. Therefore:

Hypothesis 2: High measurement error makes respondents more likely to update their partisanship during campaigns.

Hypothesis 3: Changes in the favorability of political parties make respondents more likely to update their partisanship during campaigns.

Although some previous work has studied voters’ political behavior and partisan instability in Latin America, the comparative literature has paid less attention to the substantive effects of such individual instability on voters’ behavior. For example, McCann and Lawson (Reference McCann and Lawson2003) found that Mexican voters tended to shift their partisanship, ideology, and presidential approval, among other attitudes, during the 2000 presidential election, particularly among voters with lower levels of education. However, it is not clear what the implications of such shifts are for voters’ behavior. During political campaigns, in fact, there are multiple paths by which partisan instability can influence voters’ behavior; the following hypotheses consider candidate evaluations and vote choice.

Candidate evaluations constitute a major element of what the early Michigan school of voting behavior referred to as the “funnel of causality” that leads to vote choice (Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and StokesCampbell et al. 1960). Voters use their partisan attachments as a shortcut for making political judgments (Reference BartelsBartels 2000; Reference Sniderman, Lupia, McCubbins and PopkinSniderman 2000) and filter campaign information, particularly rejecting the information that is inconsistent with their political predispositions (Reference ZallerZaller 1992). If partisan bias influences candidate evaluations, voters will worsen their evaluation of opposition candidates over the course of the campaign, but the evaluation of their copartisan candidate will remain stable. In other words, citizens acquire information and tend to confirm and reinforce their prior beliefs while rejecting information that contradicts precampaign considerations (Reference KundaKunda 1990; Reference Taber and LodgeTaber and Lodge 2006; Reference NirNir 2011). However, we should expect important variation among voters with short-term and long-term partisanship; only those voters who have built long-term partisan attachments are likely to reinforce their candidates’ evaluations during campaigns (e.g., candidate feeling thermometer). On the contrary, voters with short-term partisanship will not be able to engage in partisan reinforcement:

Hypothesis 4: Long-term partisans are more likely to reinforce their candidate evaluations over the course of the campaign.

Hypothesis 5: Short-term partisans are less likely to reinforce their candidate evaluations over the course of the campaign.

A second path whereby partisanship influences voters during campaigns is vote choice; partisanship ultimately guides which candidate voters will support. As the literature posits, political campaigns help voters support the candidate in line with their preexisting political predispositions (Reference Berelson, Lazarsfeld and McPheeBerelson, Lazarsfeld, and McPhee 1954; Reference Erikson and WlezienErikson and Wlezien 2012; Reference Gelman and KingGelman and King 1993). Because campaigns activate voters’ political predispositions, the connection between partisanship and vote choice is stronger as a campaign unfolds (Reference Gelman and KingGelman and King 1993). If some partisans update their partisanship as a campaign unfolds, this has important implications for the relationship between voters’ partisan attachments and vote choice: only those voters who have built long-term partisan attachments are likely to reinforce their vote choice, which makes them immune to campaigns. On the contrary, voters with short-term partisanship will be more likely to change their vote choice, because they do not have partisan attachments that are strong enough to interpret new information in a manner that reinforces their vote choice. Therefore:

Hypothesis 6: Long-term partisans are more likely to reinforce their vote choice over the course of the campaign and, therefore, are less likely to change their vote preference.

Hypothesis 7: Short-term partisans are less likely to reinforce their vote choice over the course of the campaign and, therefore, are more likely to change their vote preference.

The following section discusses how short- and long-term partisanship conditions voters during campaigns in young democracies, focusing on the 2006 and 2012 presidential elections in Mexico after the country’s transition to democracy in 2000.

Partisan Instability in Latin America

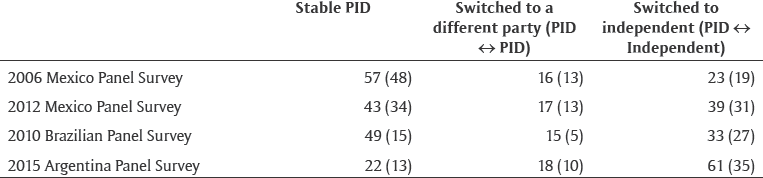

The comparative literature in Latin American political behavior suggests that some voters have unstable partisan attachments (Reference LupuLupu 2013; Reference Baker, Ames, Sokhey and RennóBaker et al. 2016). Table 1 shows that a very high proportion of voters in presidential elections in Brazil (50 percent) and Argentina (70 percent) updated their party identification between the beginning and end of the campaign. While the literature on voting behavior expects that some partisans self-identify as independents in some conditions (e.g., when socially desirable; see Reference Keith, Magleby, Nelson, Orr and WestlyeKeith et al. 1992; Klar and Krupnikov 2013), a striking proportion of partisans changed their declared identification to another political party by the end of the campaign. Table 1 also shows that about half of the electorate updated its partisan attachments in the 2006 and 2012 presidential elections in Mexico. Around a third of partisans transitioned to independents, and the rest changed their identification from one party to another. In other words, partisan instability is not a characteristic of a particular electoral cycle; it persists over time and across different Latin American party systems.

Table 1: Stability of party identification between panel survey first and second waves by percentage of partisans (percentage of sample in parentheses).

Notes: Stable independents: Mexico 2006 (17%), Mexico 2012 (20%), Argentina 2015 (40%), Brazil 2010 (47%). Stable PID = reports the same party identification over time; PID ↔ PID = change from identifying with a party to another party; PID ↔ Independent = change from identifying with a party to independent (or vice versa).

There are several reasons this research focuses on the Mexican party system. From a survey research perspective, as suggested in recent studies (Reference Castro CornejoCastro Cornejo 2019b), the question wording used in the Mexico Panel Surveys (Reference Lawson, Domínguez, Greene and MorenoLawson et al. 2007, Reference Lawson, Baker, Bruhn, Camp, Cornelius, Domínguez, Greene, Magaloni, McCann, Moreno, Poiré and Shirk2013) is the only one among Latin American panel surveys that avoids survey strategies that underestimate percentage of partisans and conceptually differentiate partisanship from voting behavior by framing partisanship as a long-term identification, as early theories of voting behavior propose (Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and StokesCampbell et al. 1960; Reference Lewis-Beck, Jacoby, Norpoth and WeisbergLewis-Beck et al. 2008). While the Argentina Panel Survey (Reference Lupu, Gervasoni, Oliveros and SchiumeriniLupu et al. 2015) relies on question wording that is framed as a long-term identification, it includes a filter question (“Regardless of which party you voted for in the last election, or you will vote for, in general, do you sympathize with any political party? If yes, which party?”). This particular wording is likely to underestimate the percentage of partisans because it makes respondents less willing to identify as partisan even though many of them do consider themselves as close to a political party.Footnote 4 Instead of directly asking the question about party as in the Mexico Panel Survey (e.g., “Generally, would you consider yourself panista, priista, or perredista?”), the Argentina Panel Survey inquires first whether voters identify with a political party; if the respondent answers yes, the interviewer asks a follow-up question on which political party the respondent most closely identifies with. As suggested by Blais et al. (Reference Blais, Gidengil, Nadeau and Nevitte2001), filtering makes it “too easy” for respondents to say no, and this tendency might be particularly important for topics in which a negative response is socially desirable (e.g., Reference Keith, Magleby, Nelson, Orr and WestlyeKeith et al. 1992; Reference Krupnikov and KlarKrupnikov and Klar 2016).

The question wording used by the Brazil Panel Survey (Reference Ames, P, Rennó, Samuels, Smith and ZuccoAmes et al. 2013) is framed as a short-term identification and also includes a filter question: “Do you currently identify with a political party? If yes, with which political party do you identify?” This wording makes voters less willing to self-identify as partisan; in fact, electoral studies that use the short time horizon have found party identification to be less stable over time vis-à-vis alternative measures, because such wording is very responsive to voters’ short-term economic and political evaluations (Reference Abramson and OstromAbramson and Ostrom 1991).Footnote 5 In fact, some of the results found by Baker and colleagues (Reference Baker, Ames, Sokhey and Rennó2016)—changing parties’ reputations driving voters’ partisan instability—might be partially explained by the question wording used by the Brazil Panel Survey.

The Mexican system also provides an ideal case to test the stability of partisan attachments from a theoretical perspective. Previous studies on voters’ partisan attachments have examined cases in which the system has experienced party brand dilution, and partisan instability has mostly been explained by variations at the party system level (e.g., on party convergence in Argentina, see Reference LupuLupu 2013; on changing party reputations in Brazil during the period 2002–2006, see Reference Baker, Ames, Sokhey and RennóBaker et al. 2016). Up until 2015, the Mexican party system did not experience the collapse of major parties or the entire system, as did many Latin American countries (Reference MorganMorgan 2011; Reference LupuLupu 2014), or the emergence of new major parties (Reference MainwaringMainwaring 2018), which allows for a focus on the analysis on variations at the individual level.Footnote 6

While Mexico is a relatively young democracy, the parties that constitute the Mexican system have been in place for quite some time—an authoritarian successor party like the PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party) (Reference Flores-Macías, Loxton and MainwaringFlores-Macías 2018) and opposition parties like the PAN (National Action Party) and PRD (Party of the Democratic Revolution) that were key actors during Mexico’s transition to democracy—Greene and Sánchez-Talanquer (Reference Greene, Sánchez-Talanquer and Mainwaring2018) refer to these as “historical legacies.” Thus, while democracy is new, both elections and the major parties in the system are established features of Mexican politics. Moreover, the party system has remained stable since the country’s transition to democracy in terms of stability in the main contenders, interparty electoral competition, and stability of parties’ ideological positions (Reference MainwaringMainwaring 2018); therefore, the brands of the three major parties are fairly strong for the average of Latin American parties.

Partisan Instability in Mexican Presidential Elections (2006–2012)

As a young democracy, the Mexican electorate has experienced a shorter period of political learning than in advanced industrial democracies. Therefore, while Mexico reports an important proportion of the electorate that self-identifies with a political party (around two-thirds of the electorate, according to the Comparative Study of Electoral Systems, CSES; figure A1 in the appendix), we should expect some variation in voters’ ability to build stable partisan attachments. To test Hypothesis 1 of this research, the first challenge is to measure the length of voters’ partisanship. While continuously advanced industrial democracies can rely on a voter’s age or number of years the respondent has had the right to vote, in young democracies political experience is necessarily limited by the country’s democratic experience.Footnote 7 Thus, the following analysis relies on the 2006 Mexico Panel Survey, which asked partisans about the number of years they have identified with their preferred party (“For how long have you identified with the … ?”).Footnote 8 At that time, it had been only nine years since the PRI lost the majority in Congress and only six years since it lost the presidency. However, some voters might have identified with a party for a longer period, because the three major parties were key actors during the transition period.

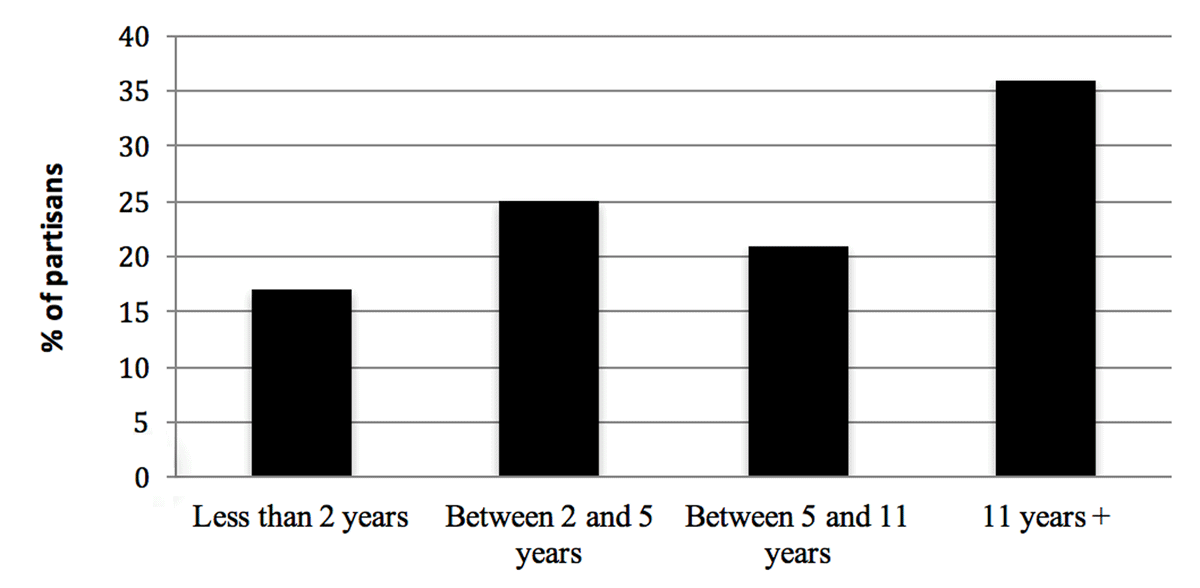

Figure 1 shows variation in the length of party identification in Mexico: 36 percent have identified with their party for more than eleven years, 22 percent between five and eleven years, 25 percent between two and five years, and 17 percent have identified for two years or less (the variable was originally coded by the Mexico Panel Survey with four categories so cannot be disaggregated into a continuous variable). Given this variation, it is expected that voters who have identified with a party for fewer years are more likely to change their party identification throughout the campaign period, whereas voters who have identified for a longer period are more likely to develop strong partisan attachments immune to election fluctuations.Footnote 9

Figure 1: Duration of party identification.

Table 2 displays results from multinomial logistic regressions based on the 2006 Mexico Panel Survey to understand which variables are associated with voters’ partisan instability.Footnote 10 The dependent variable differentiates several scenarios of partisan instability (stable party identification, switches to another party identification or switches to independent). Crossing party lines during the campaign—that is, in a relatively short period—seems to be a very drastic change compared to voters who switch to independent. To assess why some voters change their party identification, there are three important takeaways from the coefficient estimates in Table 2. First, length of party identification is measured by the number of years a respondent has identified with a party (Hypothesis 1).Footnote 11 Second, the models include a favorability index measuring the change of opinion of the respondents’ preferred party in order to measure changes in party reputations (Hypothesis 3).Footnote 12 The index is based on respondents’ evaluations of their preferred party on a 0–10 scale, measured during the first and second wave of the 2006 Mexico Panel Survey. Positive values mean that the opinion of their preferred party improved; negative values mean that it worsened throughout the campaign. Similarly, it includes a favorability index measuring changes in respondents’ copartisan candidate following the same operationalization. In separate models, it also includes a combined favorability index of respondents’ preferred party and copartisan candidate, as the inclusion of both indices might have produced multicollinearity.

Table 2: Multinomial logistic regression (2006 presidential election in Mexico).

Notes: Dependent variable is partisanship instability (base category = stable PID). Standard errors in parentheses.

*** p < 0.01; ** p < 0.05; * p < 0.1.

The models also consider respondents’ survey-taking behavior (Hypothesis 2) as the source of instability in party identification (Reference Green and PalmquistGreen and Palmquist 1990, Reference Green and Palmquist1994). While previous studies have relied on panel studies with multiple waves to measure respondents’ consistency over time, the Mexico Panel Surveys do not have enough waves to follow such operationalization.Footnote 13 Instead, the analysis relies on an index combining five questions in which the interviewer evaluates whether the respondents’ survey-taking behavior was evasive, uninformed, rushed, distracted, and/or bored, as opposed to open, smart, calm, attentive, and/or interested.Footnote 14 In addition, the index includes the number of “don’t know” answers accumulated during each survey interview.Footnote 15 This index measures what the survey research literature refers to as “survey satisficing” (Reference Vannette, Krosnick, Ie, Ngnoumen and LangerVanette and Krosnick 2014), which can significantly increase measurement error. Some voters might not be sufficiently motivated to answer the survey interview and generate answers quickly on the basis of “little thinking,” which makes them more likely to provide inconsistent answers to the party identification question during panel surveys (Reference Castro CornejoCastro Cornejo 2019a).

Models 1–3 evaluate which variables are associated with respondents’ crossing of party lines between the beginning of the campaign and election day. Model 1 shows that length of partisanship is associated with partisan switching (p < 0.05): voters who have identified with a party for fewer years are more likely to cross party lines during the campaign period. Only those voters with a long period of identification have partisan attachments strong enough to endure political campaigns. Similarly, consistent with previous research, Model 1 finds that party and candidate favorability is associated with crossing party lines: voters who worsened their views of their copartisan candidate and their preferred candidate are more likely to switch identification to alternative parties (p < 0.01). These findings are consistent with earlier studies that posited that in young democracies, partisan switching is rooted in voters changing their views on their preferred party. However, the findings of Model 3 suggest that the effect of voters’ views on preferred party and candidates is moderated by voters’ weakly entrenched partisan attachments. Model 3 reports the interaction between voters’ length of partisanship and an index that combines changes in both respondents’ preferred party favorability and copartisan candidate favorability, which is statistically significant (p < 0.05).

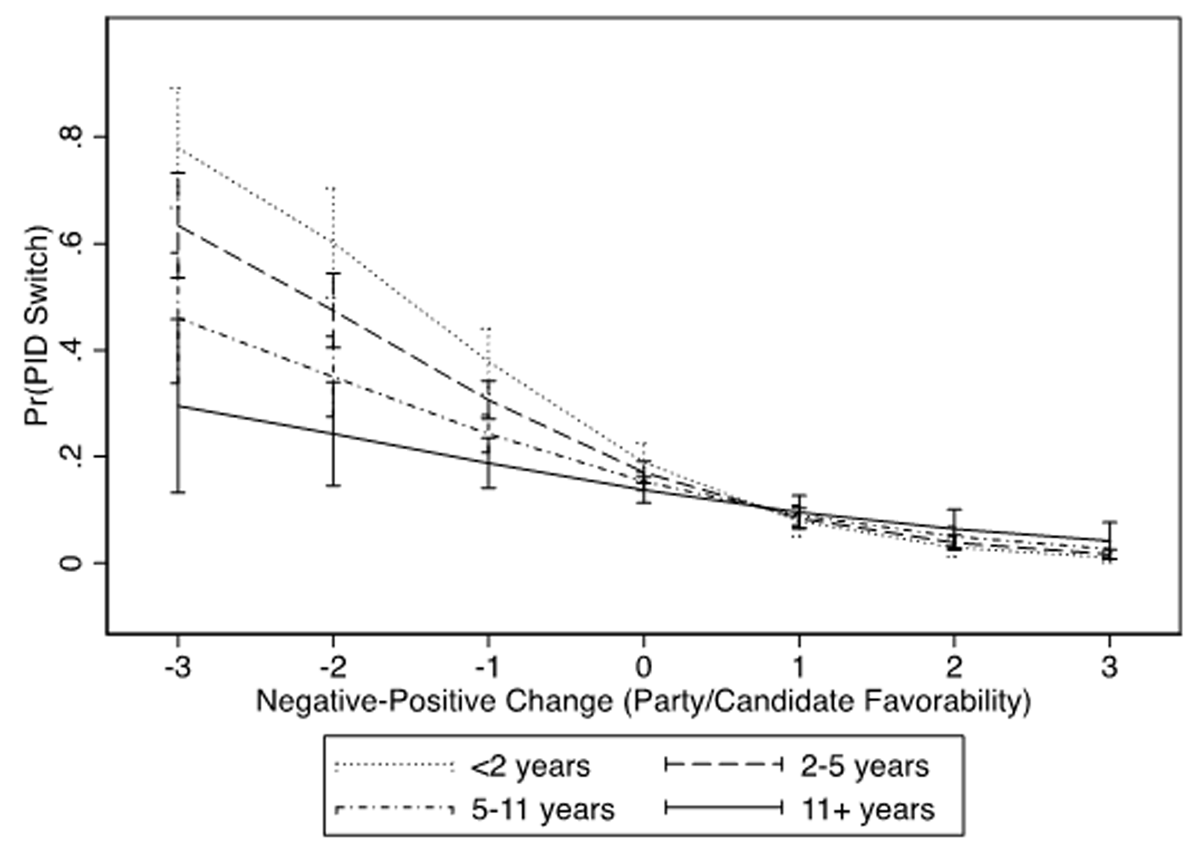

For ease of interpretation, Figure 2 reports the probability of crossing party lines. Positive values mean that the opinion of the copartisan candidate and the respondent’s preferred party improved, and negative values mean that it worsened throughout the campaign. Figure 2 shows that voters who have identified with their preferred party for a very short period are more likely to cross party lines when their views of their preferred party worsen. However, voters who hold party identification for a longer period are significantly less likely to engage in partisan switching, even when their views of preferred candidate and party worsen throughout the campaign. For example, a partisan who reports a very negative change is very likely (around 80 percent) to cross party lines when identifying with their preferred party for fewer than two years, but only 30 percent likely when identifying for more than eleven years. Based on Figure 2, we can be certain that “less than two years” and “between two and five years” of party identification are significantly different from identifying with one for “more than eleven years.” Only the confidence intervals for “between five and eleven years” and for “more than eleven years” tend to overlap when the party or candidate favorability deteriorates. The results suggest that there is a point at which short-term partisanship develops into a more entrenched partisan attachment. Voters are able to use partisanship as the screen through which they observe the political world and are more likely to dismiss negative views of their preferred party rather than switching their partisan allegiance.

Respondents’ survey-taking behavior is not associated with crossing party lines (p > 0.10). However, switching to identification as independent seems to be associated with respondents’ behaviors during the survey interview (Models 4–6). Model 4 shows that partisans who switch to independent are significantly more likely to be evaluated by the interviewer as evasive, uninformed, rushed, distracted, and/or bored and report more “don’t know” answers during the survey interview (p < .01). In turn, partisans who change to independent do not differentiate in years of partisanship or their views on their copartisan candidate. However, partisans who switch to independent do report changes on their preferred party during the campaign. Figure 3 reports the probability of switching to independent throughout the campaign. Changing views of their preferred party period is associated with a twenty-five-point increase in the probability of switching to independent. In turn, respondents’ survey-taking behavior is associated with a thirty-three-point increase.

Figure 2: Conditional effect of length of partisanship on the effect of (candidate + party) favorability change on the likelihood of partisan switching.

Figure 3: Probability of switching to independent.

Overall, while there is some uncertainty, particularly among the most extreme observations (Figure 3 shows very high levels of inattentive respondents or a very negative change in party favorability), both length of partisanship and party favorability seem to make voters more likely to change their partisanship during the beginning of the campaign and election day. In other words, while some measurement error may be driving such shifts (survey satisficing, particularly when shifting to independents), voters also seem to change their partisanship as a result of changing perceptions about parties during campaigns.

How Does Partisan Instability Affect Voters’ Candidate Evaluations and Vote Choice?

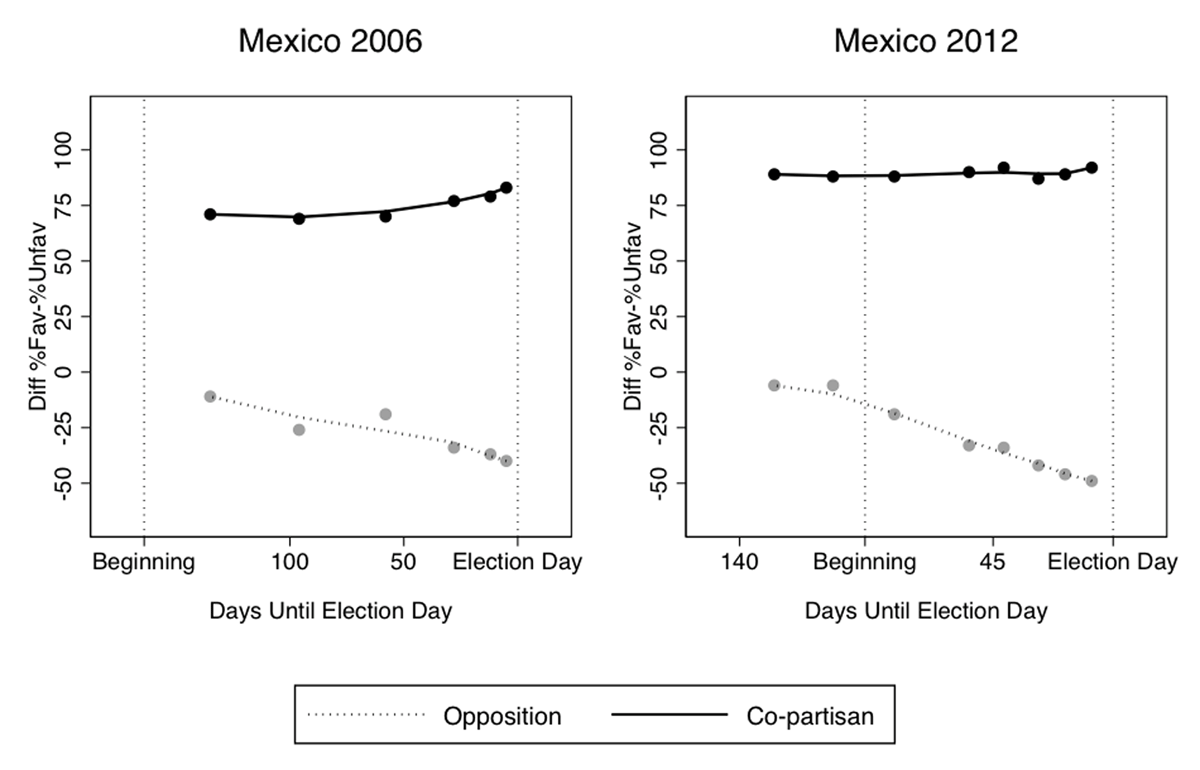

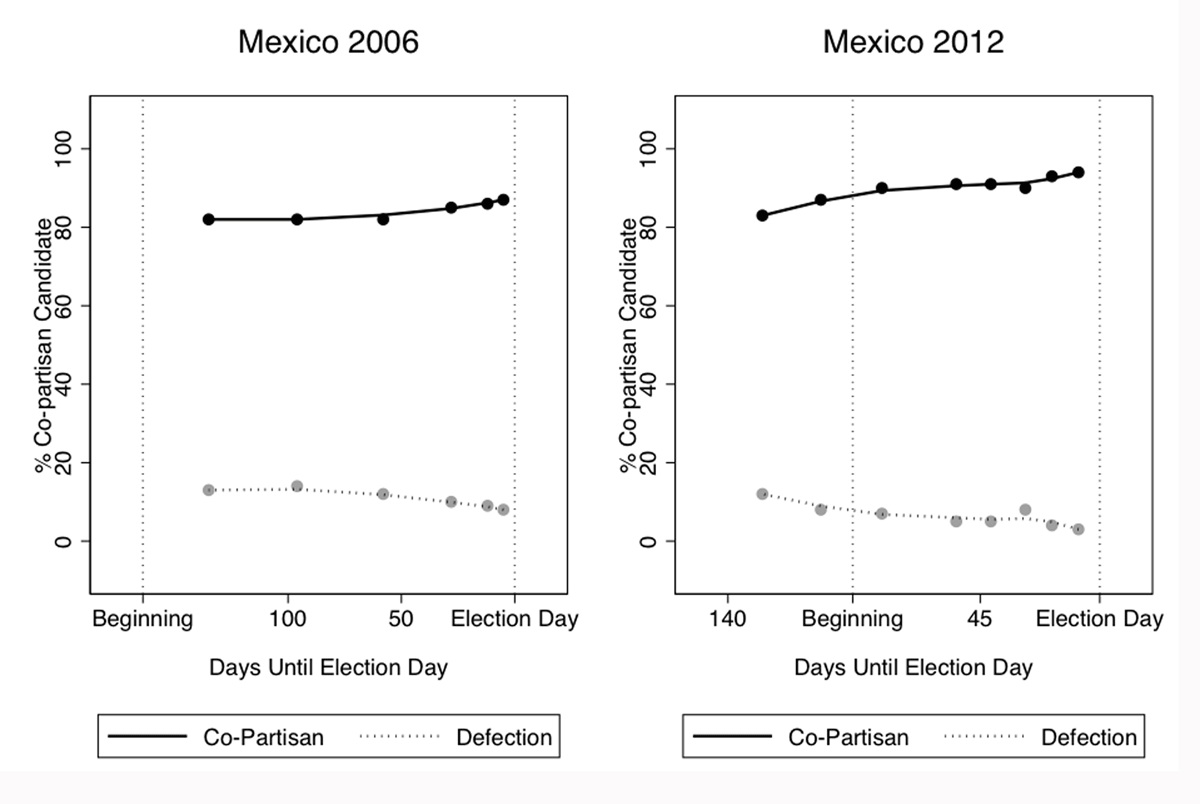

Consistent with Hypotheses 4 and 5 it is expected that only those long-term partisans are able to reinforce their candidates’ evaluations during campaigns. On the contrary, short-term partisans will not be able to reinforce their candidate evaluations. For those purposes, the following analysis relies on data not only from the Mexico Panel Survey but also from fourteen nationally representative polls conducted during the 2006 and 2012 presidential elections in Mexico.Footnote 16 Figure 4 provides evidence that partisans in both presidential elections reinforce their precampaign candidate evaluations, and it shows the average of net candidate favorability of the three major candidates competing in both campaigns based on cross-sectional data (PRI, PAN, and PRD candidates). Because it measures the difference between favorable and unfavorable opinions, positive values mean that voters’ opinion improved and negative values that it worsened (range from-100 to 100).Footnote 17 The evaluations of copartisan candidates are very stable throughout both campaigns and even improved slightly during the 2006 presidential campaign (+75 in 2006 and +89 in 2012). However, evaluations of the opposition candidate, which worsen significantly as election day approaches, are far from stable. For example, in 2006 the opposition candidates registered an average net favorability of –11 at the beginning of the campaign and fell to –40 by the end of the campaign. In 2012, the difference was even larger: from –6 to –49.

Figure 4: Candidate net favorability ratings.

While cross-sectional analysis can measure candidate evaluations among self-declared partisans at a given point, it cannot distinguish whether those partisans changed their partisan allegiance throughout the campaign. Thus, Figure 5 presents the probability of voters changing their opinion of their copartisan candidate based on data from the 2006 and 2012 Mexico Panel Surveys (see Table A3 in the online appendix for complete ordinary-least-squares regressions). The dependent variable is respondents’ copartisan candidate favorability—in particular, a change in favorability between the first and second wave of both panel surveys.Footnote 18 Positive values mean that opinions of the copartisan candidate improved and negative values that it worsened. Figure 5 shows that only voters with stable partisanship throughout the campaign have strong enough partisan attachments to interpret new information so as to reinforce (p < 0.01, Hypothesis 4). In turn, voters with unstable partisanship have a harder time to filter campaign information: rather than reinforce their precampaign predispositions, they are more likely to worsen their views of the candidate that coincide with their party identification at the beginning of the campaign (p < 0.01, Hypothesis 5).Footnote 19 The results support the notion that voters with short-term partisan loyalties behave differently than partisans with long-term attachments: they are more likely to have a deteriorated opinion of their copartisan candidate.

Figure 5: Copartisan candidate favorability. P → P = changed party identification; P → I changed from partisan to independent.

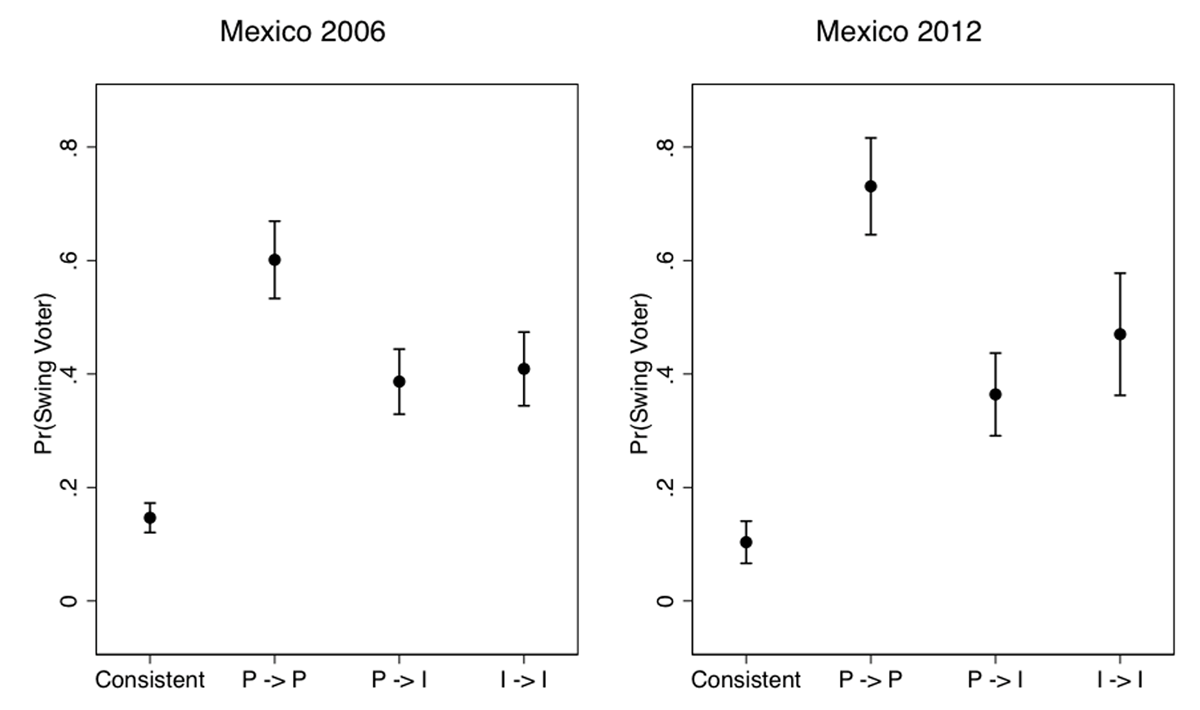

To test Hypotheses 6 and 7, Figure 6 provides evidence that a significant proportion of partisans in Mexico support their copartisan candidate. Figure 6 averages the copartisan vote for the three major candidates competing in both campaigns based on cross-sectional data (PRI, PAN, and PRD candidates, fourteen national representative polls). While in 2006 the connection between partisanship and vote choice slightly increased throughout the campaign (from 82 percent to 87 percent),Footnote 20 in 2012, the connection became much stronger, increasing from 83 percent to 94 percent.

Figure 6: Support for copartisan candidate.

However, as in the case of candidate evaluations, vote choice based on cross-sectional data cannot speak to the behavior of partisans who update party identification throughout the campaign. Figure 7 displays the predicted probabilities of changing vote choice based on data from the 2006 and 2012 Mexico Panel Surveys (see Table A4 in the appendix for complete ordinary-least-squares regressions).Footnote 21 The dependent variable in each model is the likelihood of changing vote preference. As expected, voters with stable partisanship tend to have stable vote choice over the course of the campaign; they report the lowest likelihood of changing vote preference (15 percent on average for both the 2006 and 2012 presidential elections). Interestingly, partisans who identify with a different party by the end of the campaign are the voters most likely to change their vote intention throughout the campaign (beyond 60 percent; p < .01)—they even report greater likelihood of vote changing than do self-identified independents (40 percent on average; p < .01). Moreover, partisans who shifted to independents tend to behave more like independents than partisans: 37 percent changed vote preference during campaigns. These findings are robust for the 2006 and 2012 presidential elections. The results support the notion that voters who have been able to build long-term partisan attachments are the most likely to reinforce their vote choice and constitute the least vulnerable group to political campaigns (p < 0.01). Short-term partisans, in turn, are vulnerable to campaigns (p < 0.01).

Figure 7: Vote choice and PID stability. P → P = changed party identification; P → I changed from partisan to independent.

These findings suggest that while long-term partisans have developed a strong attachment to parties, short-term partisans fit the description of rational theories of voting behavior (“running tally”) because they update their partisan attachments as they gather more information about parties and candidates. This means that campaigns in young democracies like Mexico are fundamental to voters’ political learning because they tend to structure voters’ political perceptions (Reference WeberWeber 2012).

How Persuadable Are Partisans in Presidential Elections in Mexico?

Understanding the direction in which partisans switch their vote choice can help us understand the influence of campaigns on voters’ partisanship. Table 3 identifies the type of campaign effect that partisans experienced between the beginning and the end of the campaign. Partisans can consistently support their copartisan candidate, reinforcing their precampaign predispositions throughout the campaign (reinforcement, #1, Table 3). Voters can also switch their vote to “return home.” In other words, supporting their copartisan candidate in case they were supporting an alternative candidate at the beginning of the campaign (“return home,” #2, Table 3). In both cases, by the end of the campaign voters ended up supporting the candidate best aligned with their political predispositions. On the contrary, partisans might have also defected from their copartisan candidate to support an alternative candidate by the end of the campaign (“defection,” #3, Table 3). Finally, it is possible that some partisans consistently support candidates even against their partisan predispositions (“against their partisanship,” #4, Table 3). In these last two cases, by the end of the campaign voters will support a candidate not aligned with their political predispositions.

Table 3: Type of vote shift throughout the campaign from wave 1 to wave 2.

Table 3 presents the type of vote shifts that partisans experienced during the 2006 and 2012 Mexican presidential elections. The few voters with long-term partisan attachments who were not supporting their copartisan candidate by the beginning of the campaign returned home (7 percent and 4 percent, respectively), for a very strong connection between partisanship and vote choice: 90 percent and 94 percent of stable partisans supported their copartisan candidate in both presidential elections. In other words, on average, only 8 percent of voters with long-term partisan attachments supported a candidate not aligned with their precampaign predispositions. This degree is fairly similar to the electoral behavior of partisans in advanced industrial democracies like the United States (e.g., only 6 percent of partisans voted against their partisan predispositions during the 2008 US presidential election; see Table A5 in the appendix). However, voters with less entrenched partisan attachments tend to report different behavior. Voters who self-identify as both partisans and independents during the campaign period (short-term partisans) report a weaker connection, 70 percent and 77 percent, respectively.Footnote 22 Broadly speaking, almost a third of them defected and supported a candidate against their precampaign predispositions.

Finally, voters who updated party identification by crossing party lines do not by definition have clear partisan predispositions, which makes the connection between partisanship and vote choice a pointless measure. However, although it is not possible to make a causal claim, it is possible to trace the direction of the partisan shift vis-à-vis vote choice. Data from the 2006 and 2012 Mexico Panel Surveys suggest that party identification shifted in the same direction as vote choice: among voters who change their vote intention and crossed party lines, a substantial majority did it following their updated vote intention (76 percent and 88 percent, respectively). Because these voters have not been able to develop long-term partisanship, their partisan attachments seem to be a reflection of their voting behavior, both of which changed over the course of the campaigns. The findings suggest that for these voters, partisanship and vote choice are empirically intertwined (Reference DinasDinas 2014).

Discussion

The findings of this study have important implications for the campaigns literature and provide nuance to the understanding of how partisanship works in young democracies like Mexico. On the one hand, the findings are consistent with the comparative literature that suggests that in third-wave democracies, voters are qualitatively different from those in advanced industrial democracies (Reference Mainwaring, Torcal, Katz and CrottyMainwaring and Torcal 2006). In young democracies like Mexico, some partisans hold weakly formed partisan attachments, which makes them vulnerable to political campaigns. However, the findings differ from those studying current campaigns by identifying which types of partisans are the most likely to be most responsive to campaigns. Voters who lack long-term partisan attachments and have identified with a political party for fewer years have a harder time filtering and rejecting campaign information inconsistent with their precampaign political predispositions and contribute to an increase in the proportion of voters who change their vote intention in a given election. Similarly, this study differs from conventional wisdom in comparative political behavior that suggests that partisanship in young democracies is weak, making partisans highly persuadable during campaigns. Stable partisans report electoral behavior fairly similar to that of partisans in US elections: they report very stable vote choice throughout campaigns, demonstrating a strong connection between partisanship and the vote. These voters have built partisanship as the screen through which they observe the political world, leading them to interpret new information so as to reinforce.

The findings also contribute more broadly to the literature in comparative politics. For example, in the case of the Mexican party system, it was puzzling that while electoral data reported low levels of electoral volatility compared to the regional average (Reference MainwaringMainwaring 2018), campaign studies have pointed out that partisans are very persuadable, switching their vote preference during campaigns. As this study finds, only short-term partisans are persuadable during campaigns. In turn, the “true partisans” (long-term partisans) report very high stability in vote choice. These findings are consistent with recent studies arguing that partisanship in Mexico is stronger than conventional wisdom has considered (Reference Castro CornejoCastro Cornejo 2019b) and more consistent with the way the Mexican party system has evolved since the country’s transition to democracy: it is a party system with a high proportion of partisans and low levels of electoral volatility.

A relevant question is on the role of short and long-term partisanship beyond the Mexican party system. Although the democratic experience and strength of party roots in Mexican society do not equate to those of advanced industrial democracies like the United States, it is higher than the regional average. If this study is replicated in party systems in Latin America in which new parties tend to appear in each election cycle and parties are more delegitimized (Reference Mainwaring and ScullyMainwaring and Scully 1995; Reference MainwaringMainwaring 2018), a larger proportion of partisans might report partisan instability and be vulnerable to campaign events and candidates’ appeals. In that sense, the results reported here may be conservative. Similarly, future studies should study the consistency of party identification during longer periods of time. While most studies in young democracies report aggregate changes on levels of partisanship across elections, measuring changes at the individual level for longer periods of time beyond political campaigns might provide further information on the conditions under which some voters in young party systems update their party identification—even crossing party lines.

Additional File

The additional file for this article can be found as follows:

• Appendix. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.638.s1

Acknowledgements

For comments and feedback, the author thanks Scott Mainwaring, Michael Coppedge, Geoffrey Layman, and Debra Javeline. The author also thanks Leticia Juarez and Ulises Beltrán (BGC, Beltrán, Juárez y Asocs) for access to their survey data sets. This work was supported by the University of Notre Dame’s Kellogg Institute for International Studies. The data and code can be found at https://www.rodrigocastrocornejo.com/publications.html.