Article contents

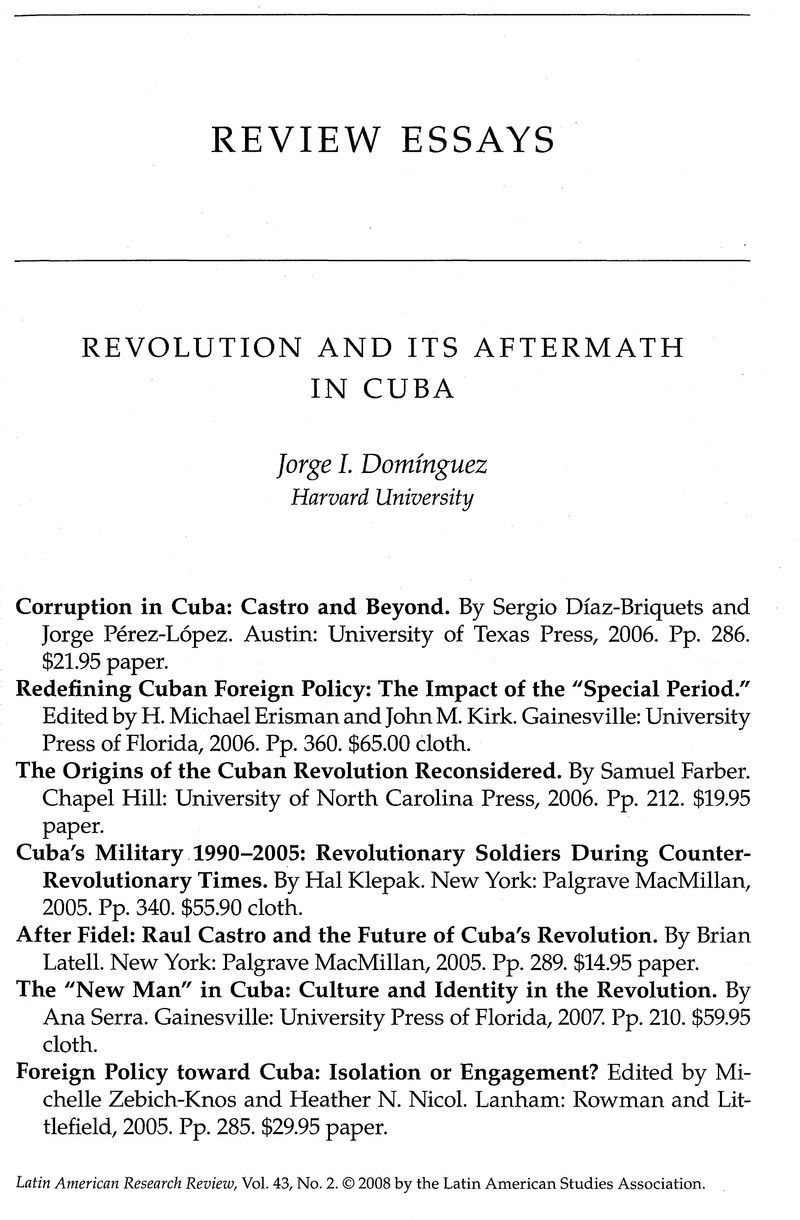

Revolution and its Aftermath in Cuba

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 September 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 2008 by the University of Texas Press

References

1. Piero Gleijeses, Conflicting Missions: Havana, Washington, and Africa, 1959–1976 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 503–510.

2. Fidel Castro and Nikita Khrushchev, “Letters between Castro and Khrushchev,” in Cuba on the Brink, ed. James G. Blight, Bruce J. Allyn, and David A. Welch (New York: Pantheon Books, 1993), 481–491.

3. Autocrítica is a much-neglected early practice of Communist Party rule in Cuba. It has been neglected because, under its name, much abuse has been committed against adversaries of the government and the party. Yet it is a good voluntary scholarly practice. Thus I have written that my Cuba: Order and Revolution (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1978) paid insufficient attention to the role of ideas in the Cuban revolutionary process and, thereby, to the impact of agency. For autocrítica on this and other matters, see my Cuba hoy: Analizando su pasado, imaginando su futuro (Madrid: Editorial Colibrí, 2006), 27–34.

4. Jorge I. Domínguez, To Make a World Safe for Revolution: Cuba's Foreign Policy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989), 286; see also discussion at 285–289.

5. Klepak also discusses corruption in enterprises associated with Cuba's military (97–101).

6. As with much public evidence on crime in any country, in the 1990s the perception of corruption in Cuba may have increased more than its actual practice. Defectors since the late 1980s reported more about corruption in Cuba than about political persecution, for example. Embassies and international journalists posted to Cuba are also more likely to report on corruption.

7. Realists take domestic circumstances into account as well as a wide panoply of factors for international influence. Neorealists are less likely to be interested in the domestic circumstances of the “units” or countries in the international system and focus more on states than on international organizations, transnational relations, and so on. Neoconservatives have strong ideological motivations, which realists and neorealists eschew. Realists like Morgenthau and neorealists like John Mearsheimer opposed U.S. policy with regard to the Vietnam and Iraq wars, respectively.

8. Klepak has chapters in both foreign policy books but writes about Cuban relations with Latin America generally in Erisman-Kirk and about Cuban relations with Mexico in Zebich-Knos-Nicol, not about military confidence building as he did in his book.

9. I have spent a significant portion of my professional career actively opposing most U.S. policies toward Cuba.

10. Among many examples of valuable social research, see Haroldo Dilla, Gerardo González, and Ana Teresa Vincentelli, Participación popular y desarrollo en los municipios cubanos (Havana: Centro de Estudios sobre América, 1993); see also Aurora Vázquez Penelas and Roberto Dávalos Domínguez, eds., Participación social: Desarrollo urbano y comunitario (Havana: Universidad de La Habana, 1998).

11. An example of such scholarly collaboration is Carmen D. Deere, Niurka Pérez Rojas, Cary Torres Vila, Miriam García Aguiar, and Ernel González Mastrapa, Güines, Santo Domingo, Majibacoa: Sobre sus historias agrarias (Havana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 1998).

12. “The leaders of the revolution have children just beginning to talk who are not learning to say ‘daddy’ They have wives who must be part of the general sacrifice of their lives to take the revolution to its destiny,” in “Socialism and Man in Cuba,” Che Guevara and the Cuban Revolution (Sydney: Pathfinder, 1987), 259.

- 1

- Cited by