No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

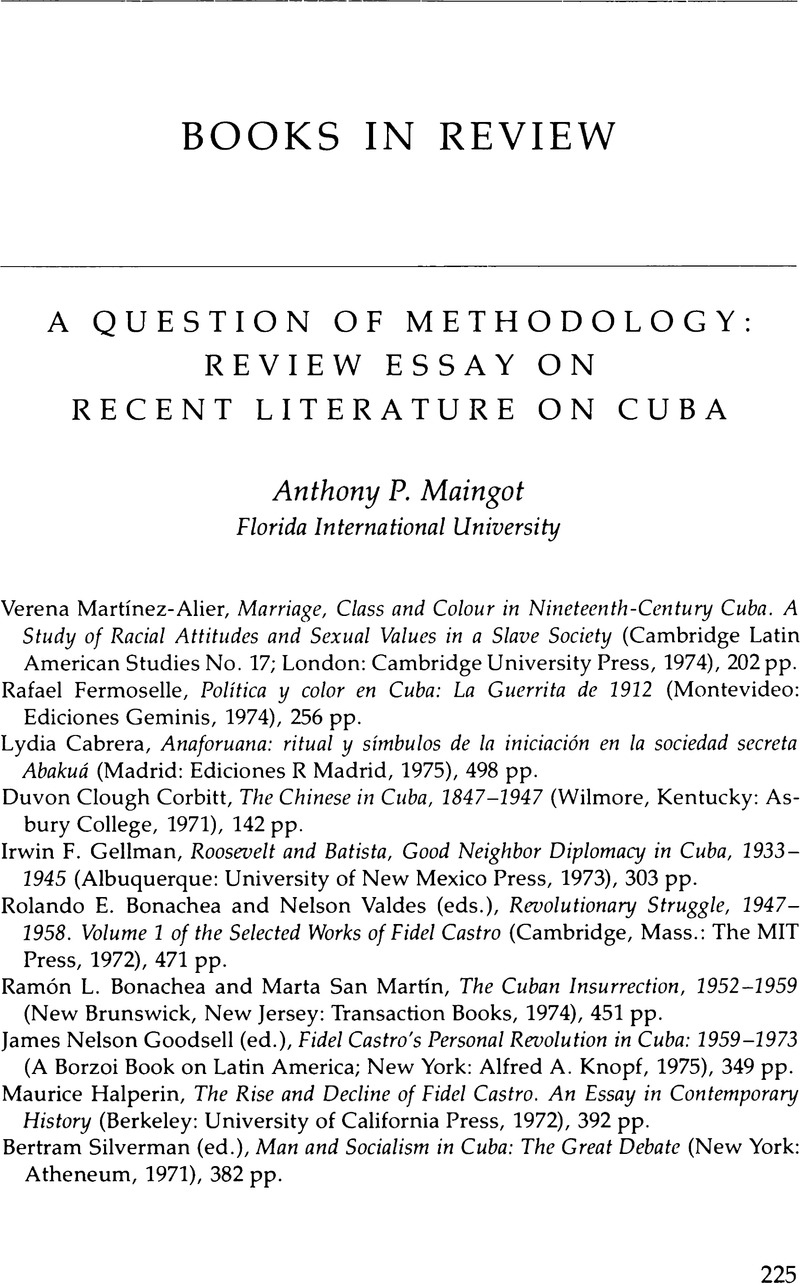

A Question of Methodology: Review Essay on Recent Literature on Cuba

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Books in Review

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1978 by the University of Texas Press

References

Notes

1. Evidence of this value can be seen, for instance, in the extensive use made of it in Oscar Pino-Santos' El asalto a Cuba por la oligarquía financiera Yanki (La Habana: Casa de las Américas, 1973). This book—which won the 1973 Premio Casa de las Américas—also contains important inputs from a group of North American researchers.

2. Sugar and Society in the Caribbean: An Economic History of Cuban Agriculture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1964). Noteworthy in this English edition is the extensive foreword by Sidney W. Mintz.

3. Two official reports of limited circulation were published in the early 1950s: International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Economic and Technical Mission to Cuba, Report on Cuba, Findings and Recommendations of an Economic and Technical Mission Organized by the IBRD in Collaboration with the Government of Cuba in 1950 (Washington, D.C.: IBRD, 1951); and International Cooperation Administration, Office of Labor Affairs, Summary of the Labor Situation in Cuba (Washington, D.C.: Department of Labor, December 1956).

4. A good idea of this productivity can be gotten from Nelson P. Valdes and Edwin Lieuwen, The Cuban Revolution: A Research Study Guide (1959–1969) (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1971), and Earl J. Pariseau (ed.), Cuban Acquisitions and Bibliography (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1970).

5. Harry Hoetink, “Cuba and the New Experts,” Caribbean Studies 1, no. 2 (April 1961): 16–21.

6. Representative of this group are the works by Fulgencio Batista, as for instance, Cuba Betrayed (New York: Vantage Press, 1962); Manuel Urrutia Leo, Fidel Castro and Co., Inc.: Community Tyranny in Cuba (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1964); Teresa Casuso, Cuba and Castro, translated by Elmer Grossberg (New York: Random House, 1961); Earl E.T. Smith, The Fourth Floor, An Account of the Castro Communist Revolution (New York: Arlington House, 1969); Mario Lazo, Dagger in the Heart (New York: Funk and Wagnall, 1968); Rufo López-Fresquet, My Fourteen Months with Castro (Cleveland, Ohio: World, 1966).

7. René Dumont, Is Cuba Socialist? (New York: Viking, 1974), which first appeared in French as Cuba est-elle socialiste? (Paris: Seuil, 1970); K. S. Karol, Guerrillas in Power: The Course of the Cuban Revolution (New York: Hill and Wang, 1970); Hugh Thomas, Cuba: The Pursuit of Freedom (New York: Harper and Row, 1971).

8. Suárez's most important work is Cuba: Castroism and Communism, 1959–1966 (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1967). The most interesting of Mesa-Lago's essays are reprinted in his edited reader, Revolutionary Change in Cuba (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1971).

9. See The Cuban Studies Newsletter 1, no. 1 (December 1970), published by the Center for Latin American Studies, University of Pittsburgh. Since January 1975 (5, no. 1) appearing as Cuban Studies/Estudios Cubanos in journal format.

10. A much less significant study is Roland T. Ely's Cuando reinaba su majestad el azúcar (Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana, 1963).

11. There are two significant dissertations worth noting: Thomas T. Orum's “The Politics of Color: The Racial Dimension of Cuban Politics during the Early Republican Years, 1900–1912” (New York University, 1975), which makes a significant contribution to our understanding of what he considers Cuban “schizophrenic society”—“one face for foreign contact [white], another for its own activities [flexible],” (p. x); and Donna Marie Wolf, “The Caribbean People of Color and the Cuban Independence Movement” (University of Pittsburgh, 1973), deals with the pan-Caribbean influences and contacts of black and colored Cubans. A significant as well as fascinating theme.

12. One of the few items on this subject available to me in the Biblioteca José Martí in 1974 was Serafín Portuondo Linares, Los independientes de color, 2nd. ed. (La Habana: Editorial Librería Selecta, 1950). This is a sympathetic attempt at explaining the motives behind the PIC's rebellion.

13. This fear was given monumental proportions by stories—not all veridical by any means—of black atrocities during the Haitian Revolution. The fear of black vengeance became an integral part of the Caribbean intellectual milieu. For the use of this fear by English, Spanish, and French see C. L. R. James, The Black Jacobins (New York: Random House, Inc., 1963).

14. Wolf, “The Caribbean People.”

15. Hugh Thomas notes that Fidel Castro never mentioned race prejudice in any of his speeches or programs before the Revolution. According to Thomas, Castro first addressed himself to the question in reply to a North American journalist on 23 January 1959, a fact that he says indicates that “racial prejudice in old Cuba was not overwhelming” (Cuba, pp. 1120–21). This assessment notwithstanding, Thomas' subsection on “Black Cuba” (pp. 1117–26) stands as clear testimony to the importance of race in prerevolutionary Cuba. The role of race in revolutionary Cuba has yet to be given scholarly attention.

16. Most important is her El Monte, originally published in 1954 and reprinted by Ediciones Universal, Miami, Florida, 1975. See also her Cuentos negros de Cuba (Madrid: Ramos, 1972) with the original 1940 prologue by Fernando Ortiz.

17. The best statement on this is contained in Harry Hoetink, Caribbean Race Relations: A Study of Two Variants (London: Oxford University Press, 1967).

18. See Leo Kuper and M. G. Smith, Pluralism in Africa (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1971).

19. See Robert R. Palmer, “Generalizations about Revolutions: A Case Study,” in Louis Gottschalk (ed.), Generalization in the Writings of History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1963), pp. 66–76.

20. Quoted in Silverman, Man and Socialism, p. 4.

21. Friedrich Engels, “The Tactics of Social Democracy,” in Robert C. Tucker (ed.,) The Marx-Engels Reader (New York: W. W. Norton, 1972), p. 407.

22. E. J. Hobsbawm, “Karl Marx's Contribution to Historiography,” in Robin Blackburn (ed.), Ideology in Social Science (London: Fontana/Collins, 1972), p. 279.

23. R. Hart Phillips, Cuban Sideshow (Havana: Cuban Press, 1935), p. 1. Mrs. Phillips was New York Times correspondent in Havana until 1959.

24. Ibid., p. 317.

25. Ibid., p. 318.