No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 October 2022

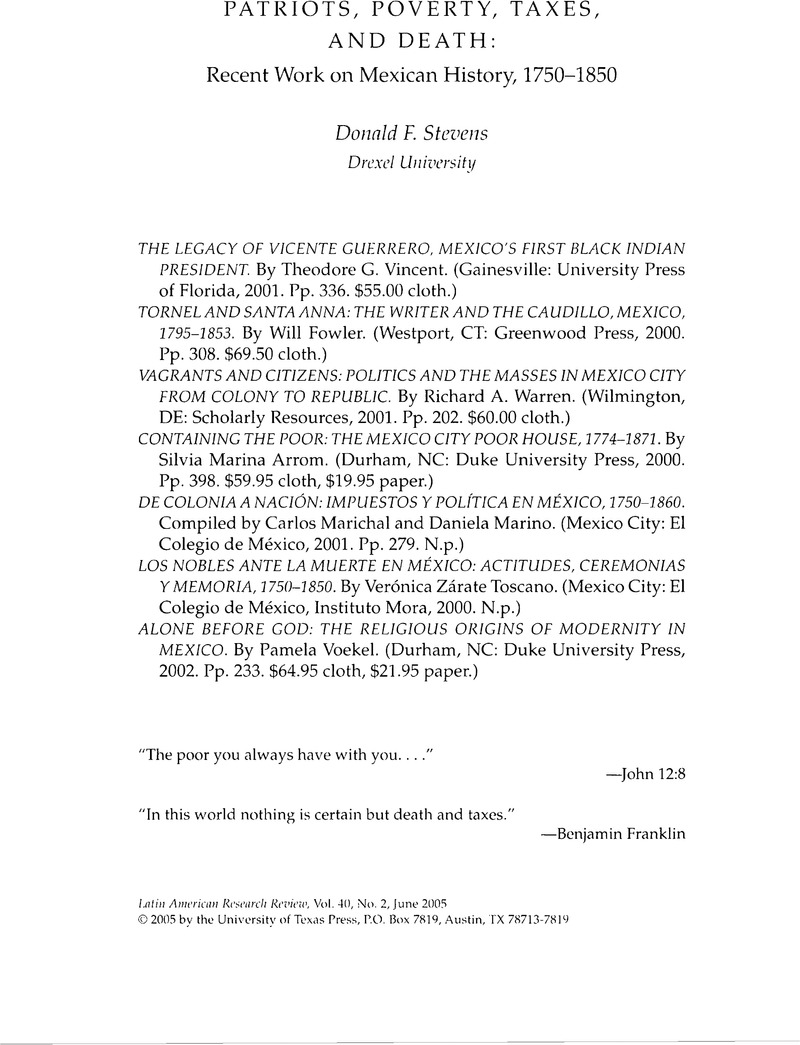

1. The first was William Forrest Sprague, Vicente Guerrero, Mexican Liberator, a Study in Patriotism (Chicago: R. R. Donnelley, 1939). Two dissertations have been written in English: Eugene Wilson Harrell, “Vicente Guerrero and the Birth of Modern Mexico, 1821–1831.” (PhD diss., Tulane University, New Orleans, 1976); Mario S. Guerrero, “Vicente Guerrero's Struggle for Mexican Independence, 1810–1821.” (PhD diss., University of California, Santa Barbara, 1977). Although Vincent cites Sprague frequently, Harrell's and Guerrero's dissertations do not appear in his bibliography.

2. Margaret Chowning, “Elite Families and Popular Politics in Early Nineteenth-Century Michoacán: The Strange Case of Juan José Codallos and the Censored Genealogy,” The Americas 55 (1): 36, 44–45 (July 1998).

3. He describes Codallos as having “African descent” (207) and as having “African descent neglected in the histories” (217). The most egregious example of Vincent's tendency to conflate appearance and reality is his caption for a photo of an ancient Olmec head, which reads, “The Olmec civilization of 1200–300 B.C.E. had contact with Africa, as evidenced in the basalt sculptured heads of the type shown here from the Museum of Anthropology in Xalapa” (2).

4. Appendix 2 contains the “The Guerrero/Riva Palacio Family Tree,” rather than documentation for racial categories in table 3.

5. Vincent, who is usually eager to describe any possible evidence of African genes, relegates the mention of Tornel's background to the notes at the end of the book, (n. 7, 196); Tornel was from an “Español” family“ (n. 46, 299).

6. Anachronistic expressions, apparently intended to make the setting familiar to modern U.S. readers, abound in this book. A few examples: black poets “rapping in verse” (51), “freedom fighter” (101, 103, 110), “funky” used as a positive descriptor (105), “affirmative action” (147), “People's Party” (158ff), the Parian market described as a “mall” (170, 173) or a “social hangout for the elite” (170), “indigenous homeland” (171).

7. The only other major biography of Tornel is María del Carmen Vázquez Mantecón's thinly documented, La palabra del poder: Vida pública de José María Tornel, 1795–1853 (Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1997).

8. Nettie Lee Benson, The Provincial Deputation in Mexico: Harbinger of Provincial Autonomy, independence, and Federalism (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1992); Donald Fithian Stevens, Origins of Instability in Early Republican Mexico (Durham: Duke University Press, 1991); Donald F. Stevens, “Economic Fluctuations and Political Instability in Early Republican Mexico,” Journal of Interdisciplinary History 16: 645–65 (Spring 1986). Quoted phrase from Marichal, appears on p. 47.

9. Eric Van Young, “Recent Anglophone Scholarship on Mexico and Central America in the Age of Revolution (1750–1850),” Hispanic American Historical Review 65 (4): 683–723 (November 1985).