Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 October 2022

1. The Leviathan of my title echoes trebly those of Thomas Hobbes, the builders of the modern Mexican state, and Carlo Collodi (Carlo Lorenzini, 1826-1890), author of The Adventures of Pinocchio (1883). In the 1940 Disney version, Pinocchio is swallowed by Monstro the whale and makes his escape by building a fire in the animal's belly, which causes Monstro to sneeze and expel the boy-puppet and his father, Gepetto. In Collodi's original story, the great sea creature is not a whale but a “Dog-fish” two miles long. Father and son make their escape by creeping out the creature's mouth while it is asleep, without the aid of any incendiary devices. In the Old Testament, leviathan is alternately identified as a crocodile, a whale, or a dragon. The epigraph is drawn from “C. Collodi” (Carlo Lorenzini), Pinocchio: The Story of a Puppet (New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1914), 212.

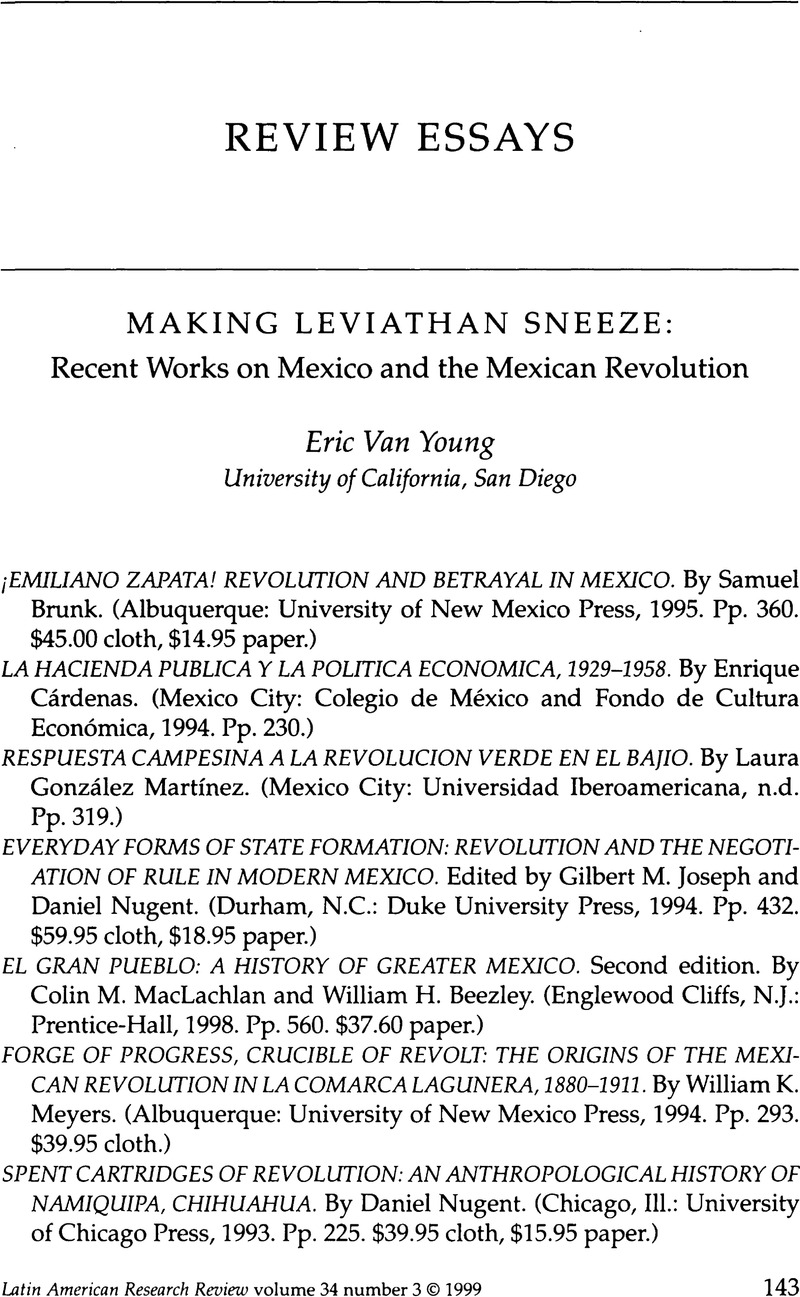

2. Other works mentioned in this review essay include Héctor Aguilar Camin and Lorenzo Meyer, In the Shadow of the Mexican Revolution: Contemporary Mexican History, 1910-1989 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1993); Ana María Alonso, Thread of Blood: Colonialism, Revolution, and Gender on Mexico's Northern Frontier (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1995); Marjorie Becker, Setting the Virgin on Fire: Lázaro Cárdenas, Michoacán Peasants, and the Redemption of the Mexican Revolution (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995); and Allen Wells and Gilbert M. Joseph, Summer of Discontent, Seasons of Upheaval: Elite Politics and Rural Insurgency in Yucatán, 1876-1915 (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1996).

3. This scenario is the one generally adopted by Aguilar Camin and Meyer in In the Shadow of the Mexican Revolution. For example, they attribute the belief in a historical teleology leading up to the Great Revolution “to all Mexican leaders, starting with Venustiano Carranza” (p. 159). But the authors themselves seem to share this view as well.

4. Insightful discussions of these issues are to be found in a number of other recent works, including Rituals of Rule, Rituals of Resistance: Public Celebrations and Popular Culture in Mexico, edited by William H. Beezley, Cheryl A. Martin, and William E. French (Wilmington, Del.: Scholarly Resources, 1994); and Mary Kay Vaughan, Cultural Politics in Revolution: Teachers, Peasants, and Schools in Mexico, 1930-1940 (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1997). Even when critical of the prevailing regime and its abandonment or distortion of the social program of the revolution, some prominent Mexican intellectuals have managed to produce a sort of semi-officialist history. For a scathing critique in this light of Enrique Krauze's Mexico: Biography of Power, translated by Hank Heifitz (New York: Harper Collins, 1997), see the recent review essay by Claudio Lomnitz, “An Intellectual's Stock in the Factory of Mexico's Ruins,” American Journal of Sociology, no. 103 (1998):1052-65. Krauze's response, Lomnitz's rejoinder, and Krauze's last word appeared respectively in Milenio, 18 May 1998, pp. 40-43; 25 May 1998, pp. 38-40; and 1 June 1998, pp. 3-5. Aguilar Camín and Meyer's In the Shadow of the Mexican Revolution exemplifies in some measure the same tendency that Lomnitz criticizes.

5. See also the books by Alonso, Becker, and Wells and Joseph cited in note 2.

6. For a useful airing of some of the potentials and problems of the “new cultural history” of Mexico, see Hispanic American Historical Review 79, no. 2 (May 1999), in which my article on the cultural history of the colonial period joins those of William French on the nineteenth century and Mary Kay Vaughan on the twentieth, along with extensive commentaries by Stephen Haber, Claudio Lomnitz, Florencia Mallon, and Susan Socolo w. Haber's extended review article fired the first salvo in what has become an interesting discussion among Mexicanist and other Latin American historians about cultural history. See Haber, “The Worst of Both Worlds: The New Cultural History of Mexico,” Mexican Studies / Estudios Mexicanos, no. 13 (1997):363-83. I will touch briefly on some of these issues in this review essay.

7. Also worthy of note in the category of political economy or economic history is Linda B. Hall, Oil, Banks, and Politics: The United States and Postrevolutionary Mexico, 1917-1924 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1995).

8. Interestingly enough, this mistake was also made by the editor of another recent work on Mexico. See Maud McKellar, Life on a Mexican Ranche, edited by Dolores L. Latorre (Bethlehem, Pa.: Lehigh University Press, 1994), 17. The error arises from the fact that this Bajío town, known in the colonial era as San Miguel el Grande, had the name of Independence hero Ignacio Allende added to it in the nineteenth century, as many other towns did. San Miguel el Grande thus became San Miguel Allende, and Ignacio Allende, Miguel Allende.

9. John Womack Jr., Zapata and the Mexican Revolution (New York: Knopf, 1969).

10. Emmanuel LeRoy Ladurie, Montaillou, the Promised Land of Error (New York: George Braziller, 1978).

11. Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude, translated by Gregory Rabassa (New York: Harper and Row, 1970); and David W. Sabean, Property, Production, and Family in Neckerhausen, 1700-1870 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

12. James C. Scott, Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant Resistance (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1985); and also Scott, Domination and the Arts of Resistance: Hidden Transcripts (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990). The latter work is less fully discussed by the essayists owing to its relatively late publication in relation to the conference. See also Philip Corrigan and Derek Sayer, The Great Arch: English State Formation as Cultural Revolution (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1985).

13. Florencia E. Mallon, Peasant and Nation: The Making of Postcolonial Mexico and Peru (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1994). The essays in the volume by Joseph, Nugent and Alonso, and Becker also prefigure monographs published the same year or slightly later.

14. Arguably, these influences were first felt in the colonial historiography, following annaliste and post-annaliste trends. The “triumphalist” narrative for the colonial era, paralleling that of the Mexican Revolution for the modern period, was the “conversion or deculturation” scenario for native peoples. Setting aside debates over White Legend versus Black Legend, this conventional wisdom began to be eaten away from the inside by careful ethno-historians and social historians at least as early as Charles Gibson's The Aztecs under Spanish Rule (1964), thirty-five years ago.

15. Steve J. Stern, The Secret History of Gender: Women, Men, and Power in Late-Colonial Mexico (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995).

16. Luis González y González, Pueblo en vilo: Microhistoria de San José de Gracia (Mexico City: Colegio de México, 1968).

17. Some of the discussion in this paragraph is drawn from my forthcoming article, “The New Cultural History Comes to the Old Mexico,” Hispanic American Historical Review 79, no. 2 (May 1999).

18. Nugent and Alonso's cultural (if not precisely culturalist) approach to northern revolutionaries and their communities can be contrasted with Miguel Tinker Salas's fine but somewhat more conventional account of Sonorense character and history in In the Shadow of the Eagles: Sonora and the Transformation of the Border during the Porfiriato (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1997). This work emphasizes the fighting of Indians, the proximity of the United States, and the advent of capitalism.