Article contents

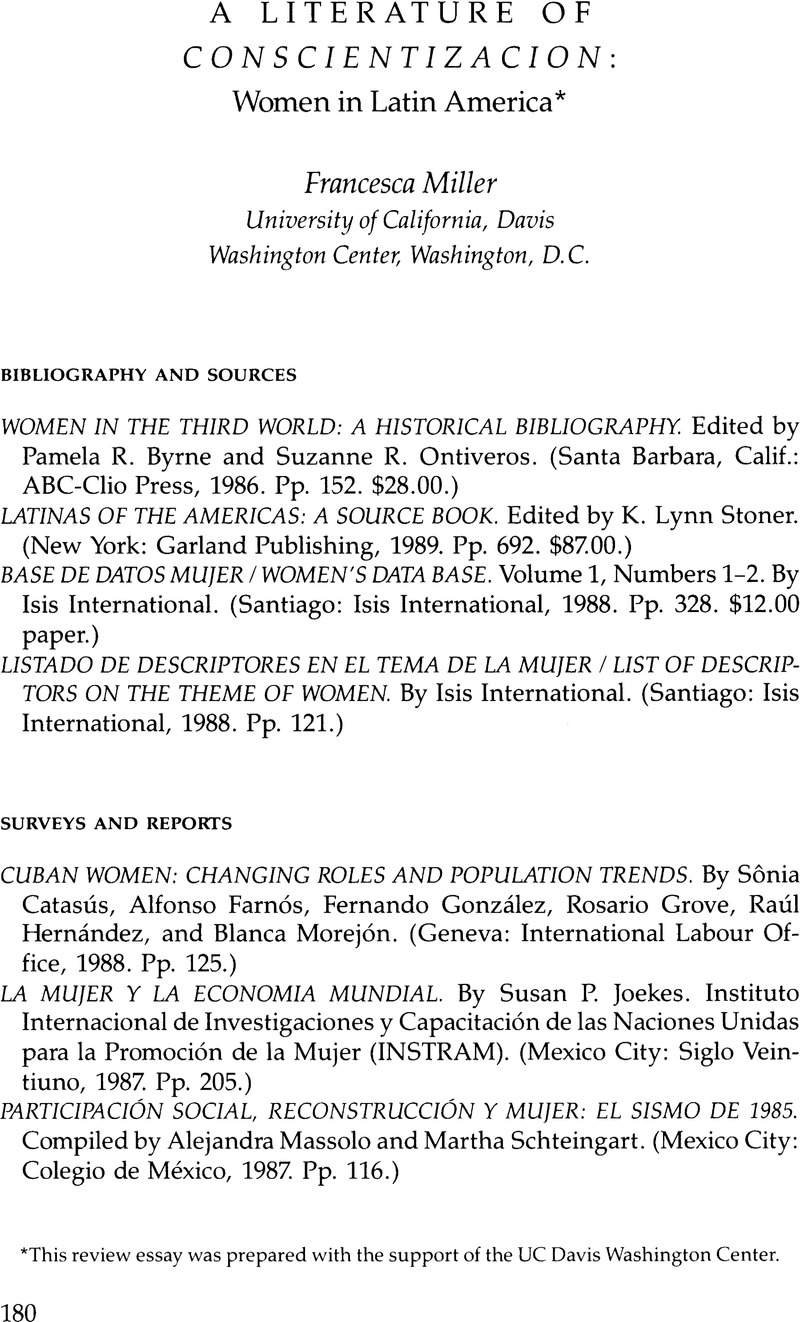

A Literature of Conscientizacion: Women in Latin America

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1992 by the University of Texas Press

Footnotes

This review essay was prepared with the support of the UC Davis Washington Center.

References

Notes

1. Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (New York: Herder and Herder, 1972).

2. Sônia E. Alvarez, “The Politics of Gender in Latin America: Comparative Perspectives on Women in the Brazilian Transition to Democracy,” 2 vols., Ph.D. diss., Yale University, 1986.

3. Congreso de Investigatión acerca de la Mujer en la Región Andina, edited by Jeanine Anderson de Velasco (Lima: Universidad Católica del Perú, 1983).

4. Temma Kaplan, “Female Consciousness and Collective Action: The Case of Barcelona, 1910–1918,” Signs 7, no. 3 (Spring 1982): 545–66.

5. Suad Joseph, “Working-Class Women's Networks in a Sectarian State: A Political Paradox,” American Ethnologist 10, no. 1 (Feb. 1983): 1–22.

6. See Asunción Lavrin, The Ideology of Feminism in the Southern Cone, 1900–1940, Latin American Program Working Paper no. 169 (Washington, D.C.: Wilson Program, 1986). See also Francesca Miller, “The International Relations of Women of the Americas, 1890–1928,” The Americas: A Quarterly Review of Inter-American Cultural History 43, no. 2 (Oct. 1986).

7. La Cacerola, Boletín Interno de GRECMU 1, no. 1 (Apr. 1984):1–16. I am grateful to Gwen Kirkpatrick for providing copies of this journal, which is published in Montevideo.

8. Lea Fletcher and Jutta Marx, “Bibliografía de/sobre la mujer argentina a partir de 1980,” Feminaria 2, no. 4 (Nov. 1989):32–34 (published in Buenos Aires).

9. González and Iracheta credit as an inspiring model of this approach to archival material Silvia Marina Arrom's The Women of Mexico City, 1790–1857 (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1985).

10. See Jean Franco's discussion of this idea in her fine monograph, Plotting Women: Gender and Representation in Mexico (New York: Columbia University Press, 1989).

11. Cited in Francesca Miller, Latin American Women and the Search for Social Justice (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 1991).

- 1

- Cited by