No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 October 2022

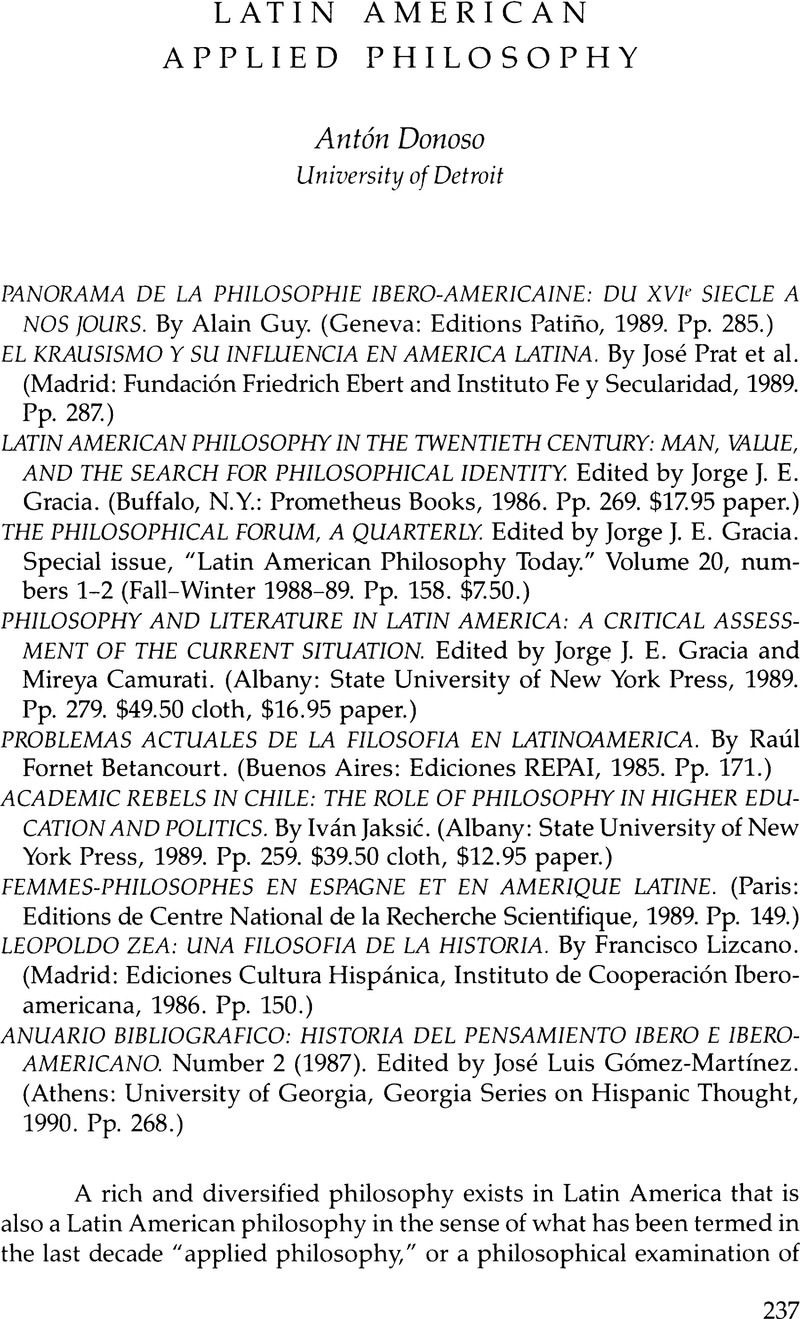

1. What sparked my curiosity were my background readings on the history of philosophy in the United States, undertaken for a dissertation at the University of Toronto on John Dewey's conception of the relation between the practical method of common sense and the scientific method. Dewey's long life (1859–1952) coincided with the professionalization of philosophy in the United States, and as I discovered, he dealt with the same European influences that affected philosophers in Latin America (even if under different names). Of my teachers, only Thomist Etienne Gilson, eminent historian of medieval Christian philosophy, had some notion of what was occurring in philosophy in Latin America. He directed me to Cornelius Krusé, who had attended the first Inter-American Conference of Philosophy in the early 1940s. See Antón Donoso, “Philosophy in Latin America: A Bibliographical Introduction to Works in English,” Philosophy Today 17, nos. 3–4 (Fall 1973):229, n. 1.

2. The founding of SILAT was the idea of the late Harold E. Davis, Professor of Latin American Studies at American University, Washington, D.C., who became its first honorary president. In 1972 Davis brought together about forty people interested in Latin American thought, ten of them professional philosophers. The papers from this conference can be found in Conference on Developing Teaching Materials on Latin American Thought for College-Level Courses, edited by Harold E. Davis (Washington, D.C.: American University, 1972). For more on SILAT's founding, early activities, and aspirations, see Antón Donoso, “The Society for Iberian and Latin American Thought (SILAT): An Interdisciplinary Project,” Los Ensayistas: Boletín Informativo, nos. 1–2 (Mar.-Oct. 1976):38–42.

3. On this topic, see the Boletín Informativo of the Sociedad Filosófica Ibero Americana (SOFIA) of Mexico. This group regularly sponsors conferences that attract leading foreign philosophers, including some from the United States and Canada.

4. SILAT has nurtured an interest among North Americans in Latin American philosophy during its three stages to date. Leading in the first stage was SILAT's first president, William Kilgore of Baylor University, a longtime participant in inter-American philosophy conferences. During this time, meetings were held in conjunction with LASA meetings. In the second phase, under the vice presidency and presidency of Oscar Martí (now at UCLA), meetings were held during the national meetings of the American Philosophical Association (APA), especially the eastern division. In the third period, under the vice presidency and presidency of Jorge Gracia of SUNY Buffalo, SILAT has been reinvigorated over the last decade. Gracia, more than any other professional philosopher in North America, has contributed greatly to disseminating knowledge of the history of philosophy in Latin America. Among his other publications is Repertorio de filósofos latinoamericanos/Directory of Latin American Philosophers (Amherst, N.Y.: Council on International Studies and Programs, State University of New York at Buffalo, 1988). Published in association with SILAT, it lists philosophers in Latin America as well as philosophers of Latin American origin living in the United States, their backgrounds, present positions, publications, and other information. Only a few of them are interested in the history of philosophy in Latin America or in Latin American philosophy, however. More information on philosophers and philosophy programs in Latin America can be found in the International Directory of Philosophy and Philosophers, 1990–1992, 7th ed., edited by Ramona Cormier and Richard H. Linebach in cooperation with Mary M. Shurts (Bowling Green, Ohio: Philosophy Documentation Center, Bowling Green State University, 1990).

5. For the history of the recent emergence of “applied philosophy” see Richard T. DeGeorge's foreword to Philosophers at Work: An Introduction to the Issues and Practical Uses of Philosophy, edited by Elliot D. Cohen (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1989). See also Cohen's introduction on the interdependence of “pure” and “applied philosophy.” For many years, the American Philosophical Association was controlled by analytic philosophers, who decided which papers were accepted and rejected papers critical of analysis or coming from nonanalytic perspectives. Only the various small independent societies that met under the umbrella of the APA (including SILAT) were open to multiple philosophical perspectives, depending on each group's purpose. During the last decade, many nonanalytic members have staged a revolt in favor of pluralism and have elected many of their candidates to offices, making the APA now more representative of philosophy in the United States.

6. See Philosophical Analysis in Latin America, edited by Jorge J. E. Gracia, Eduardo Rabossi, Enrique Villanueva, and Marcelo Dascal (Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Reidel, 1984). The Spanish edition was published as El análisis filosófico an América Latina (Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1985). See also Jorge J. E. Gracia, “Philosophical Analysis in Latin America,” History of Philosophy Quarterly 1, no. 1 (Jan. 1984): 111–12.

7. The author of numerous studies on Luis de León, Luis Vives, Miguel de Unamuno, José Ortega y Gasset, José Vasconcelos, and Samuel Ramos, Guy is noted especially for his two-volume Les Philosophes espanols d'hier et d'aujourdi hui (Toulouse: Editeur Privat, 1956).

8. Also participating was Antonio Jiménez García of the Universidad Complutense, author of El krausismo y la Institutión Libre de Enseñanza (Madrid: Editorial Cincel, 1985).

9. The Junta's innovations are treated in more detail in an essay by Eduardo Ortiz of London's Imperial College in La Junta y la nueva ciencia en España.

10. See José Luis Gómez-Martínez, Bolivia, un pueblo en busca de su identidad (La Paz and Cochabamba: Los Amigos del Libro, 1988). Also see José Luis Gómez-Martínez, “Bolivia después de 1952: un ensayo de interpretación,” Los Ensayistas: Bolivia, nos. 21–22 (Summer 1986):9–50.

11. The earlier work is Contemporary Latin American Philosophy: A Selection, with an introduction and notes by Aníbal Sánchez Reulet, translated by Willard R. Trask (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1954). A more specialized anthology was printed privately in 1961 and published two years later. See Harold E. Davis, Latin American Social Thought: The History of Its Development since Independence, with Selected Readings (Washington, D.C., 1963). Later Davis contributed a general history of Latin American thought entitled Latin American Thought: A Historical Introduction (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 1972), paperback edition (New York: Free Press, 1974).

12. See Jorge J. E. Gracia and Iván Jaksić, “The Problem of Philosophical Identity in Latin America,” Inter-American Review of Bibliography 34 (1984):53–71. Although philosophers have long been concerned with the concepts of “self” and its “identity” in the history of Western philosophy, these same philosophers have manifested no such concern for either national or ethnic identity. It seems to me that professional philosophers have something essential to contribute to these discussions—clarification of concepts and systematization of the elements of the concepts. Currently, the peoples of Canada and the former Soviet Union, to name only two political entities, have engaged in discussions and activities that have led to the dissolution of one of these nations as we have known it. It would be unfortunate if philosophers thought of themselves as being above discussing such issues.

13. See Ofelia Schutte, “Toward an Understanding of Latin American Philosophy: Reflections on the Formation of a Cultural Identity,” Philosophy Today 31 (Spring 1987):21–34.

14. See also Leiser Madanes, “Filosofía y democracia en Argentina (1983–1989),” and Celia A. Lertora Mendoza, “Panorama del pensamiento argentino actual,” both in Los Ensayistas: Argentina, 1955–1989, nos. 26–27 (1989):105–16 and 117–60.

15. See also Oscar Martí, “Is There a Latin American Philosophy?” Metaphilosophy 14 (1983).

16. For a critical study of the theological complement to the philosophy of liberation, see Arthur F. McGovern, Liberation Theology and Its Critics (Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis, 1989).

17. See Raúl Fornet Betancourt, “La pregunta por la ‘filosofía latinoamericana’ como problem filosófico,” Revista de Filosofía 22, no. 1 (May-Aug. 1989):166–88 (published in Mexico City).

18. For more on this topic, see my review of this book in Hispania 74, no. 1 (Mar. 1991):81–82.

19. See the March-April 1987 issue of Anthropos: Revista Documentatión Científica de la Cultura, dedicated to María Zambrano as “Pensadora de la Aurora.” This journal is published in Barcelona and Madrid. See also the interview with Zambrano when she became the first woman to receive the Premio Cervantes: Prólogo: Revista del Lector, no. 3 (May-June 1989): 16–22 (published in Madrid).

20. Cordua presented a paper, “The Dissolving Power of Intelligence according to Hegel,” to the conference “Skepticism in the History of Philosophy: A Pan-American Dialogue,” University of California, Riverside, 15–17 Feb. 1991. See also Cecilia Sánchez, “La búsqueda de un nuevo lugar teórico para la filosofía en Chile,” Los Ensayistas, Chile: 1968–1988, nos. 22–25 (1987–88):167–90.

21. For a North American study of Zea, see Solomon Lipp, Leopoldo Zea: From “Mexicanidad” to a Philosophy of History (Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1980). For an early essay by Zea on culture in both Americas, see Leopoldo Zea, “The Interpretation of Ibero-American and North American Cultures,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 14 (Sept. 1948-June 1949):538–43. This essay demonstrates Zea's lifelong effort to comprehend the culture of Latin America, the main task of philosophy in his view. He expresses the hope that North American philosophers will do the same for their cultures and that the philosophers of both Americas will someday attain an understanding of the American culture that is common to both. I cannot recommend this essay too highly as a clear forestatement of Zea's lifelong vocation in philosophy. U.S. interest continues in Zea's philosophy of the history of Latin America. English readers can now consult Zea, The Role of the Americas in History, edited by Amy A. Oliver, translated by Sonja Karsen (Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 1991).

22. For information on all publications on philosophy in a number of journals and books originating from Latin America, consult the quarterly listings (some with abstracts) in The Philosopher's Index: An International Index to Philosophical Periodicals and Books, which has been published for the last twenty-five years by the Philosophy Documentation Center of Bowling Green State University in Ohio.

23. SILAT continues to be active. Under President-elect Iván Jaksić, the Center for Latin America at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee sponsored a major conference entitled “Bridging the Atlantic: Iberian and Latin American Thought,” 14–16 Mar. 1991. Four of the thirteen sessions were devoted to philosophic thought, with papers or commentaries by some of the authors under review (Gómez-Martínez, Gracia, Jaksić, and Schutte) that deal with some of the subjects covered in these publications (Zea, Krausism, feminism, liberation, and dependency).