Article contents

The Inter-American System as a Liberal “Pacific Union”?

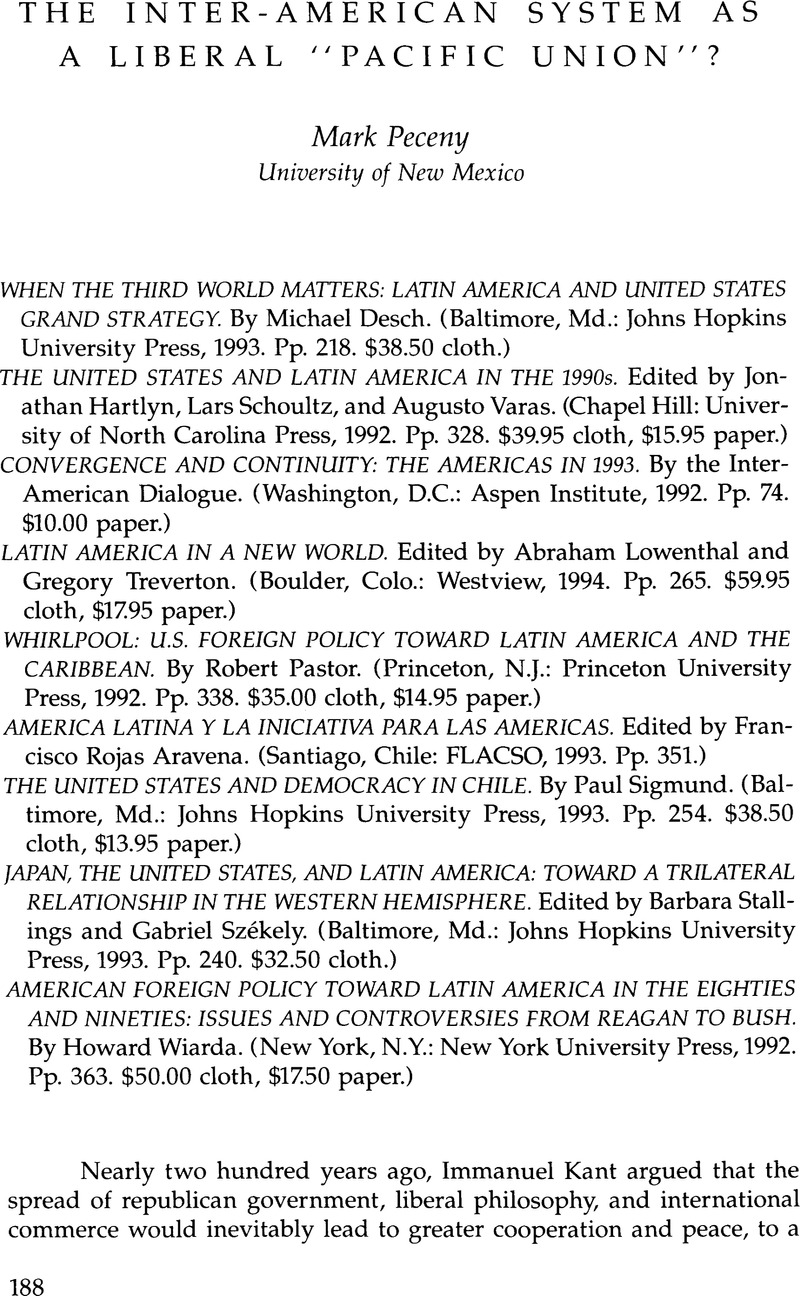

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1994 by the University of Texas Press

References

Notes

1. Immanuel Kant, “To Perpetual Peace,” in Perpetual Peace and Other Essays on Politics, History, and Morals, translated by Ted Humphrey (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1983), 107-43.

2. Michael Doyle, “Kant, Liberal Legacies, and Foreign Affairs: Part I,” Philosophy and Public Affairs 12, no. 3 (Summer 1983):205-35.

3. Richard Rosecrance, The Rise of the Trading State (New York: Basic Books, 1986).

4. Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye, Power and Interdependence, second edition (New York: HarperCollins, 1989); and James Rosenau, Turbulence in World Politics (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1990).

5. See, for example, Stallings, “Peru and the U.S. Banks: Privatization of Financial Relations,” in Capitalism and the State in U.S-Latin American Relations, edited by Richard Fagen (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1979), 217-53.

6. Wiarda seems to contradict the Kantian argument at one point, however, when he argues in another essay in this volume that the spread of democracy in the region may actually increase international tensions (see p. 74).

7. This interpretation would be consistent with the general empirical findings on this question. Although democracies rarely, if ever, fight one another, they are as likely as any other kind of state to go to war. See Steve Chan, “Mirror, Mirror on the Wall … Are the Freer Countries More Pacific?” Journal of Conflict Resolution 28, no. 4 (Dec. 1984):617-48; and Zeev Maoz and Nasrin Abdolali, “Regime Types and International Conflict, 1816-1976,” Journal of Conflict Resolution 33, no. 1 (Mar. 1989):3-35.

8. This argument does not match a conventional Kantian explanation for the frequency of wars between democracies and nondemocracies as ideological crusades on the part of liberal regimes. See Michael Doyle, “Kant, Liberal Legacies, and Foreign Affairs: Part II,” Philosophy and Public Affiars 12, no. 4 (Fall 1983):323-53.

9. Much of the recent literature on U.S. efforts to promote democracy in the region, for example, has emphasized that the dominance of security and economic considerations in U.S. policy accounts for the limited success of these efforts. See Exporting Democracy, edited by Abraham Lowenthal (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991); and Thomas Carothers, In the Name of Democracy (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1991).

10. Pastor made a similar argument in his earlier book, Condemned to Repetition: The United States and Nicaragua (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1987).

11. This viewpoint represents a distinct shift from his earlier views. As late as 1986, Wiarda argued forcefully that a policy of exporting democracy was unlikely to succeed in Latin America. For an example, see his essay “Can Democracy Be Exported: The Quest for Democracy in U.S.-Latin American Policy” in The United States and Latin America in the 1980s, edited by Kevin Middlebrook and Carlos Rico (Pittsburgh, Pa.: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1986), 325-52.

12. For a persuasive argument against this optimistic view, see Andrew Hurrell's contribution to the Lowenthal and Treverton collection (especially pp. 180-82).

13. Abraham Lowenthal, “The United States and Latin America: Ending the Hegemonic Presumption,” Foreign Affairs 55 (Fall 1976):199-213.

14. Lars Schoultz, National Security and U.S. Policy toward Latin America (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1987), 268-307.

15. Robert Bach provides a partial exception to this statement in his essay on hemispheric migration patterns, his contribution to the collection edited by Hartlyn, Schoultz, and Varas.

16. Karen Remmer, “Democratization in Latin America,” in Global Transformation and the Third World, edited by Robert Slater, Barry Schutz, and Steven Dorr (Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner, 1993), 91-112.

17. Jack Levy, “Domestic Politics and War,” in The Origin and Prevention of Major Wars, edited by Robert Rotberg and Theodore Rabb (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 88.

- 3

- Cited by