After sixteen years of inter-cartel wars for control over drug-trafficking routes, drug violence in Mexico rose to new levels following the 2006 federal intervention, when President Felipe Calderón declared war on the cartels and deployed the military to the country’s most conflictive regions. The war on drugs led to the fragmentation of Mexico’s five dominant cartels into new cartels and hundreds of smaller organized criminal groups (OCGs) and to the proliferation of multiple wars in urban and rural regions (Reference GuerreroGuerrero 2012). To finance these wars, cartels and their criminal associates expanded their activities into a wide range of criminal industries, including kidnapping for ransom, extortion, human smuggling, the looting of natural resources, and capturing municipal public resources. Whereas between 1990 and 2006 victims of intercartel wars were mainly cartel members and their private militias, after 2006 OCGs began targeting civilians and local government officials. Unlike in the past, when they primarily fought to control drug trafficking routes, after 2006 cartels and their associates used violence to gain de facto control over local governments, populations, and territories, seeking to develop subnational criminal governance regimes.

As criminal wars expanded from Mexico’s main urban centers into the country’s rural areas, cartels became particularly interested in gaining control over indigenous regions, especially in the northern and southern sierra systems. These mountainous regions are ideal places for the cultivation of marijuana and opium poppies and are also abundant in minerals and forests. They are, moreover, strategic corridors for the trafficking of illegal commodities, with multiple communication routes that connect seaports along the Pacific coastline with the US-Mexico border.

Although cartels and their associates have tried in recent years to become de facto rulers of Mexico’s mountainous indigenous regions, their success rate has been mixed. In fact, several studies have noted that, compared to urban centers, the presence of multiple OCGs and the outbreak of bitter turf wars in the country’s indigenous regions have been relatively limited (Reference Romero and MendozaRomero and Mendoza 2015).

Building on seminal arguments about the ability of small groups to provide public goods and the capacity of tightly knit communities to safeguard communal resources (Reference OstromOstrom 1990), students of political economy suggest that traditional indigenous institutions and communal practices in Mexico empower communities to solve collective action problems and become more effective public goods providers. In an influential article, Díaz-Cayeros, Magaloni, and Ruiz-Euler (Reference Díaz-Cayeros, Magaloni and Ruiz-Euler2014) show that municipal governments tend to provide public goods more effectively in indigenous communities where public decisions are taken in communal assemblies, communal service is mandatory, and elders actively participate in solving local conflicts through customary judicial practices. Communal accountability and participation result in a more equitable distribution among villagers of public utilities and education.

Do indigenous customary laws and traditions that facilitate a more effective and egalitarian distribution of economic resources enable indigenous communities to deter drug cartels from taking over their governments, populations, and territories? Do the same communal mechanisms that facilitate cooperation in the provision of public utilities operate in the area of security, when communities have to collectively confront powerful cartels?

In this article, we argue that while indigenous customary laws and traditions provide communal accountability mechanisms that make it harder for narcos to take control over indigenous villages, they are insufficient to insulate communities from narco penetration. Our central claim is that the communities that are able to resist narco conquest are those that have a history of social mobilization in which indigenous movements have played a key role in connecting communities, developing translocal bonds of trust and solidarity, and expanding village-level indigenous customary laws and traditions into regional ethnic autonomy regimes. By scaling up local accountability practices to the regional level and developing translocal networks of cooperation, indigenous movements have been able to construct mechanisms of internal control and external protection that enable indigenous communities to deter the narcos from corrupting local authorities, recruiting young men into their ranks, and imposing rule through force.

We develop our argument through a paired comparison of two similar indigenous highland regions: the Montaña/Costa Chica region of the southern state of Guerrero and the Sierra Tarahumara in the northern state of Chihuahua. These are two leading states for poppy cultivation and strategic corridors for drug trafficking, where cartels have been engaged in fierce turf wars. In these two regions, indigenous communities are ruled under customary laws and traditions. Villagers in the Guerrero highlands, however, have been able to resist and contain the narcos from their communities, while in Chihuahua the narcos violently rule. The comparison offers an initial test, showing that translocal networks of cooperation and the construction of regional ethnic institutions of policing and justice, the result of decades of mobilization, distinguish the Guerrero highlands from the Tarahumara.

On the basis of more than thirty in-depth interviews conducted with indigenous leaders, Catholic clergy, members of civic and human rights NGOs, and external advisers to indigenous communities in Guerrero and Chihuahua, we conduct a dual process-tracing exercise to identify plausible causal mechanisms that account for radically different experiences in resistance to narco rule between two similar regions.Footnote 1

A key factor explaining the different outcomes is that after a decade of intense mobilization for land and indigenous rights in Guerrero, and drawing on indigenous customary laws and traditions, indigenous movements from the Montaña/Costa Chica region developed a parallel policing and judicial regional system—the Coordinadora Regional de Autoridades Comunitarias–Policía Comunitaria (CRAC-PC)—that has largely contained the narcos. In a system where communal assemblies select, oversee, and sanction villagers who serve as regional police officers and public prosecutors, strong norms of communal accountability prevent narcos from easily capturing the police and the justice system. Because community service in policing and prosecutorial activities is unpaid and a source of honor, the system provides additional normative motivations of self-restraint that lead the regional police and the prosecutors to fight the narcos instead of colluding with them. Beyond mechanisms of internal control, the translocal networks built over decades of mobilization facilitate the flow of information across villages and foster the solidarities that allow villagers to call on hundreds of police officers from other villages to defend the system’s external borders against narco encroachment.

In contrast, in the absence of powerful indigenous movements that could have developed strong scaled-up regional ethnic autonomy institutions, isolated communities in the Sierra Tarahumara have failed to resist narco conquest. Without access to translocally networked communities to defend the external borders of the Tarahumara, villages’ internal control mechanisms have been insufficient to prevent narcos from taking over their lands, peoples, and territories.

As a test of external validity, we present the findings of a statistical analysis based on 881 indigenous municipalities from twenty Mexican states showing that the combination of indigenous mobilization and ethnic autonomy institutions can reduce the conditions that facilitate the emergence of criminal governance. This finding suggests that the mechanics of resistance we have identified in Guerrero, and their absence in Chihuahua, are not specific to our paired comparison.

Criminal Governance and Societal Resistance: Theoretical Guidelines

While the concept of criminal governance has been traditionally associated with the ability of mafia groups to regulate and protect multiple criminal markets (Reference GambettaGambetta 1993), here we follow Arias (Reference Arias2017) in expanding the concept to describe the de facto controls that OCGs exercise over subnational populations, governments, and territories. In his influential study of drug trafficking in Brazil, Jamaica, and Colombia, Arias demonstrates that drug gangs are interested in governing not only the criminal underworld but also social and political processes within specific territorial domains. Arias describes OCGs as territorial armed groups that use coercion and corruption to influence local electoral processes, the local provision of security, the allocation of public resources, and participation in civil society organizations. Controls over these sociopolitical processes enable them to secure control over the criminal underworld.

While Arias studies gangs exercising criminal governance at the neighborhood level, we focus on clusters of municipalities. Although formally elected mayors operate de jure within administrative jurisdictions, OCGs create subnational regimes of criminal governance when they develop a de facto monopoly of violence; control key appointments within municipal governments and systems of local taxation; define the rules of economic, social, and political transactions; and establish informal controls over territorial boundaries.

Scholars have focused on three factors that enable OCGs to develop subnational criminal governance regimes: rents, war needs, and political opportunity. As Chacón (Reference Chacón2018) shows, armed groups in Colombia have used targeted violence to capture fiscal transfers from national governments to municipalities in order to finance war. Blume (Reference Blume2017) and Trejo and Ley (Reference Trejo and Leyforthcoming) show that drug cartels in Mexico more commonly attack local authorities and seek to capture local governments where turf wars are more intense. Trejo and Ley (Reference Trejo and Leyforthcoming) also show that drug cartels and OCGs are more likely to develop subnational criminal governance regimes where central authorities have left local authorities politically unprotected.

While these factors help explain dynamics of criminal governance in Mexico’s urban and rural regions, they do not fully explain criminal governance in indigenous regions. The Tarahumara in Chihuahua and the eastern highlands of Guerrero had similar market appeal. Cartels had immersed both areas in protracted turf wars, and between 2006 and 2012 both states were ruled by opposition governors who were left unprotected by federal authorities. Yet the Tarahumara fell under cartel control while the eastern Guerrero highlands did not.

Building on the civil war literature, we seek to move beyond a narrow focus on cartels, war, and local government vulnerability and focus instead on the ability of local communities to resist the encroachment of drug cartels. Societal resistance, we suggest, might be a major omitted variable in this emerging debate.

Societal resistance to criminal governance

Societal resistance to nonstate armed actors has become a central issue in the study of civil war. Arjona (Reference Arjona2016) has made the important claim that the quality of prewar social institutions can play a key role in determining which communities are able to resist attempts by nonstate armed groups to take over their villages. In her study of rebel governance in Colombia’s civil war, Arjona shows that communities that developed legitimate prewar social institutions possessed the social capital to resist attempts by armed groups to become de facto rulers.

We take Arjona’s findings as a starting point, but we make an important distinction between local institutions and social movements. Focusing on Mexican indigenous communities, we distinguish between indigenous village-level customary laws and traditional practices, and pan-indigenous social movements. This distinction between (local) informal village-level institutions and (regional) social movements is crucial in helping us develop our hypothesis about communities’ differing abilities to resist narco rule.

Indigenous customary laws and traditions refer to the local, informal institutional practices of community self-governance. While these rules have changed over time and across regions, two key institutional practices are crucial. Based on principles of direct democracy, community decisions are made through community assemblies. Although the collectivity reigns, individual power, prestige, and honor are achieved through years of unpaid community service that constitute the cargo system—a system of compulsory community work. Assemblies usually elect elders with a long history of community service to play key roles in procuring local justice. These village-level informal institutions are embedded within the formal rules of municipalities and elected authorities.

Indigenous movements are translocal social networks that connect members of several indigenous villages in the articulation of public claims to the state. Mexico experienced a major wave of indigenous mobilization in the last quarter of the twentieth century (Reference MattiaceMattiace 2003; Reference TrejoTrejo 2012). Assisted by the Catholic Church and by leftist opposition parties and progressive members of state agencies, indigenous movements emerged in the 1970s and 1980s demanding land redistribution. In the 1990s they expanded their focus to include rights to ethnic autonomy and self-determination. Because the Mexican state granted only limited ethnic rights to indigenous communities, indigenous movements turned to Convention 169 of the International Labor Organization, which recognizes communities’ claim to autonomy and self-determination, in order to establish de facto subnational autonomy regimes in southern and central states.

While we recognize that indigenous customary laws and traditions generate important social norms of accountability and participation, our key claim is that in isolation these village-level informal institutions do not equip communities with adequate social infrastructure to resist and contain drug cartels. Despite their internal cohesion, isolated villages of one thousand inhabitants cannot cope with powerful cartels and their private militias. We argue, instead, that when indigenous movements are capable of scaling up these village-level institutions to connect hundreds of villages through regional ethnic autonomy regimes, indigenous communities gain access to the social and institutional infrastructure that empowers them to prevent cartels from conquering their communities. These regional ethnic autonomy institutions are the result of long histories of indigenous mobilization in which different organizational traditions—from indigenous customary practices to liberation theology to leftist secular traditions—blend to create new social institutions and translocal networks.

A major factor that distinguishes indigenous villages from each other is whether they participate in social movements and have a history of independent social mobilization. As Mattiace (Reference Mattiace2003) and Yashar (Reference Yashar2005) suggest, indigenous movements empower villages to connect with other villages in the pursuit of common goals such as land redistribution or ethnic autonomy. Through these linkages, communities can scale up local claims, making movements more resilient: if the leaders of one community become the targets of state repression or attacks by nonstate armed groups, other co-ethnic villagers can come to their rescue and prevent the movement from collapsing (Reference TrejoTrejo 2012).

We argue that these translocal networks forged over decades of mobilization empower communities to resist and contain drug cartels through two mechanisms: the cooperation and solidarity from other villages connected to the network offer them strength in numbers, providing external protections against cartel conquest; external protection then serves as a safeguard for the internal accountability controls associated with indigenous customary laws, which protect local indigenous authorities and populations from the corrupting power of the narcos.

Access to informal government protection networks is key to cartels’ success in controlling illicit markets. Various studies of drug trafficking in Mexico have demonstrated that members of the armed forces, state and municipal police forces, and officials of the justice system have played a crucial role in developing these networks (Reference Snyder and Durán-MartínezSnyder and Durán-Martínez 2009; Reference Trejo and LeyTrejo and Ley 2018). In a context of extensive collusion between OCGs and state security agents, it is crucial to develop informal institutions that are autonomous from state interference and that facilitate mechanisms of internal control and external protection in order to deter the collusion of local indigenous authorities with drug lords.

A Paired Comparison of Two Sierras

Within the universe of Mexican municipalities, Figure 1 identifies 881 indigenous municipalities with at least 10 percent indigenous-language speakers. The map singles out the two regions for comparison: the Sierra Tarahumara (Chihuahua) and the Montaña/Costa Chica region (Guerrero). These regions share a remarkable number of characteristics, summarized in Table 1, that are relevant to explaining criminal governance and societal resistance.

Figure 1 Mexican indigenous municipalities, 2010. Source: INEGI (2010).

Table 1 Paired comparison of indigenous highlands of Guerrero and Chihuahua.

a Sedena (2016).

b INEGI (2009).

c CONAPO (2010).

d Kyle (Reference Kyle2015), Mayorga (Reference Mayorga2016).

e Trejo (Reference Trejo2012).

Similar conditions

Both the Montaña/Costa Chica region and the Sierra Tarahumara have great business appeal for drug cartels. Both are mountainous, remote, and ideal places for marijuana and poppy cultivation. Estimates based on military seizures of drug plantations reveal that poppy cultivation in the municipalities surrounding the area under the control of the CRAC-PC in eastern Guerrero is equivalent to the cultivation in the Tarahumara. Both regions are ideal drug-trafficking corridors: Chihuahua borders the United States; while the Pacific coast that borders Guerrero is a landing ground for drug shipments from South America and the site of export ports for illegal trade with Asia.

Both regions share economic conditions auspicious for the development of subnational criminal governance regimes. By all counts, the Montaña/Costa Chica (approximately 150,000 indigenous inhabitants) and the Tarahumara (approximately 125,000 indigenous inhabitants) are Mexico’s most impoverished rural regions. Most households in the Montaña region of Guerrero practice subsistence agriculture, and some of the Costa Chica households are small-scale coffee producers. Most households engage in temporary migration to supplement their income. Tarahumara households in Chihuahua specialize in subsistence agriculture and also engage in temporary migrant work. The liberalization of land tenure in the 1990s and the withdrawal of state subsidies resulted in a major rural crisis, which drug cartels seized on to actively recruit indigenous households from the Sierra systems, including Guerrero and Chihuahua, to cultivate poppies.

Both Guerrero and Chihuahua experienced an outbreak of intercartel wars in the 1990s and early 2000s. The war on drugs and the deployment of the army to states in 2007 resulted in the fragmentation of the leading cartels and their transformation into warring OCGs. Between 2007 and 2017 violence in both states increased by a factor of six, and multiple cartels and their criminal associates fought not only for control over drug-trafficking routes but also over the development of subnational criminal governance regimes.

Although their institutions take different forms, indigenous communities from both the Montaña/Costa Chica region and the Sierra Tarahumara rely on indigenous customary laws and traditions. In both, a cargo system defines individual responsibilities to the community and links service to communal power. Community assemblies elect indigenous authorities, and individuals with a more active trajectory of communal service are often elected to positions of authority. Assemblies and local authorities rely on indigenous customary laws to solve local civil conflicts.

Different social processes

A crucial difference between these two regions is their prior histories of mobilization and the development of regional ethnic autonomy institutions. In the Guerrero highlands a variety of indigenous movements were part of multiple cycles of protest in the 1980s, whereas indigenous communities in the Tarahumara remained mostly disconnected and weakly mobilized. In Guerrero these experiences of mobilization for land redistribution, agricultural support, and indigenous rights led in the 1990s to one of Mexico’s most notable subnational ethnic autonomy organizations: the CRAC-PC, an informal indigenous regional judicial/policing system that has operated in eleven municipalities in the Montaña/Costa Chica region since 1995.

The CRAC-PC is the result of an extensive history of mobilization in which several cultural, political, and religious traditions overlap (Reference SierraSierra 2015). As a CRAC-PC adviser reported to us, “the community police is the institutional outcome of multiple organizational layers and experiences of mobilization.” Three groups operating in the region in the 1980s played a key role in this process: leftist secular forces, progressive state officials, and the Catholic Church.

Assisted by communist and socialist dissident groups throughout the 1980s, owners of small plots and collective landholders in the Montaña/Costa Chica region created powerful regional movements for agricultural commercialization. Sponsored by former leftist state employees who had worked at state food agencies for the poor, local farmers developed corn- and coffee-producing cooperatives (Reference Johnson and TylerJohnson 2007). Accompanied by Catholic clergy trained in liberation theology, indigenous communities in the Montaña region created a dense network of community-based Bible study groups in which community members discussed their everyday lives of economic exploitation and racial discrimination through the prism of the Christian scriptures. Building on these groups and on indigenous customary practices, Catholic clergy sponsored the development of the powerful Network of Indigenous Communal Authorities (Consejo de Autoridades Indígenas, CAIN).

In the years leading to 1992, the Catholic Church and CAIN played a key role in bringing these multiple religious and secular organizational layers into the creation of the Guerrero Council of 500 Years of Indigenous, Black, and Popular Resistance (CG-500) as part of a continent-wide movement against five hundred years of colonization. CG-500 became a pioneering group demanding the rights to autonomy and self-determination for indigenous peoples in Mexico. After the uprising of the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) in the southern state of Chiapas in 1994, Mexico’s indigenous movements accompanied the Zapatistas in a six-year nationwide mobilization and negotiation for the constitutional recognition of indigenous rights. While national negotiations between the EZLN and the federal government were under way, communities in the Montaña/Costa Chica region took the lead in developing de facto regional ethnic autonomy institutions.

In contrast to the eastern highlands of Guerrero, the communist and leftist organizations that spearheaded major struggles for land redistribution in southern Mexico have scant presence in the Tarahumara. While the Catholic Church has a long history in the Tarahumara through the Society of Jesus, the Jesuits focused their work on the cultural revitalization of communities and stayed away from developing translocal networks and movements for land redistribution or ethnic rights.

Without the connections to leftist secular forces or Catholic-sponsored social movements that might have contributed to building regional networks of resistance in the Tarahumara, the Sierra communities did not engage in the large-scale mobilizations that characterized other Mexican indigenous regions. Unlike communities in eastern Guerrero, the indigenous peoples in the Tarahumara did not take part in the widespread indigenous protests leading to the continent-wide demonstrations against the five hundredth anniversary. They were not involved in the major wave of indigenous mobilization triggered by the 1994 Zapatista rebellion, nor did they develop any meaningful movements for indigenous autonomy and self-determination after 1994.

Different outcomes

A second major difference is that indigenous communities from the Guerrero highlands and the Sierra Tarahumara have had dramatically opposing experiences in confronting narco conquest attempts: while highland communities of Guerrero have been able to contain the narcos, cartels have violently colonized the Tarahumara.

Rival cartels have waged major turf wars in the Tarahumara and have used lethal violence to gain control over the region. If we consider organized-crime-related murders committed in the 2007–2012 period, the average municipal rate per 100,000 population in the Tarahumara was 53.63. In contrast, the rate in CRAC-PC municipalities was 11.81—the lowest in Guerrero, Mexico’s most violent state (Reference Trejo and LeyTrejo and Ley forthcoming).

Cartels and their criminal associates have murdered local authorities and party candidates to gain control over local governments and populations in the Tarahumara. Between 2007 and 2012 cartels committed seven high-profile lethal attacks. In contrast, they committed two attacks in the CRAC-PC region—the lowest in Guerrero, the leading state in high-profile attacks (Reference Trejo and LeyTrejo and Ley forthcoming).

Cartels have succeeded in gaining control over the political process, the police, and key local government operations in several municipalities in the Tarahumara. These positions of de facto power have enabled them to gain control over local communities, recruit young indigenous males into the cartels, and force communities to harvest poppies. In contrast, in the Montaña/Costa Chica region, communities have largely contained the narcos.

By controlling for a large number of characteristics that both regions share, our analysis suggests that the translocal networks built over decades of mobilization and the regional policing and judicial institutions associated with the CRAC-PC might be the key factors that explain why communities have contained the cartels in eastern Guerrero, while narcos govern in the Tarahumara. However, other possible factors should be considered.

Alternative Explanations

We consider two potential alternative explanations: first, that the Montaña/Costa Chica region is less valuable to the narcos than the Tarahumara; and second, that residentially mobile communities in the Tarahumara were less capable of resisting the narcos as social organization there was more difficult than in eastern Guerrero.

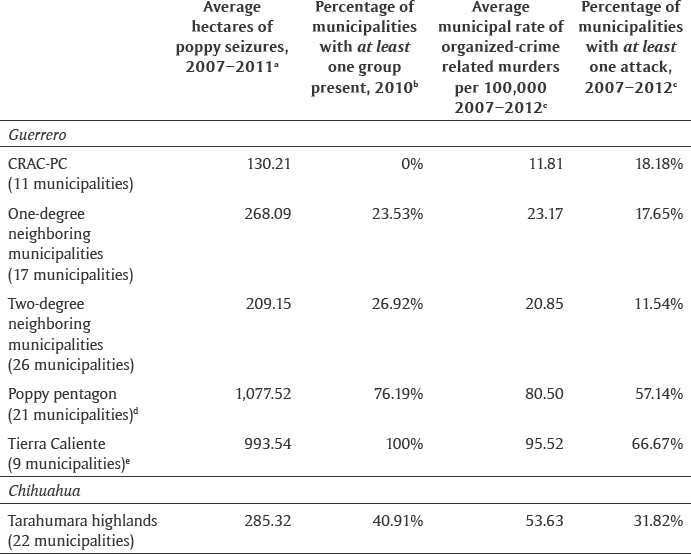

To assess the value of the two regions, Table 2 compares the eleven municipalities under the CRAC-PC system with their immediate and nearby neighbors, municipalities that constitute Guerrero’s poppy pentagon (a major poppy cultivation region), municipalities from the Tierra Caliente region (a nonindigenous region similar to the Montaña/Costa Chica region), and the Tarahumara in Chihuahua.

Table 2 Drug activity and cartel violence in Guerrero and Chihuahua.

a Sedena (2016).

b Coscia and Ríos (Reference Coscia and Rios2012).

c Trejo and Ley (Reference Trejo and Leyforthcoming).

d Grecko and Espino (Reference Grecko and Espino2015).

e Zepeda Gil (Reference Zepeda Gil2018).

The information reveals that Guerrero is as valuable (or more so) than Chihuahua but that cartels have been unable to expand to the region under CRAC-PC control. Crucially, if we use poppy seizure as a proxy of cultivation, the information in the first column suggests that the neighboring municipalities of the CRAC-PC region are as valuable as the Tarahumara. Drug cultivation, as reported in the first column, was low in the CRAC-PC region because, as shown in the second and third columns, the cartels had limited reach, despite their active presence in neighboring municipalities. Drug lords have sought to expand the frontiers of the poppy pentagon into the eastern highlands of Guerrero, a fertile ground for poppy cultivation, but have been contained. Because of their limited presence, no significant turf wars have occurred. As the third column shows, the murder rate associated with turf wars is between two and eight times lower in the CRAC-PC region than in the rest of Guerrero. While cartels have murdered municipal authorities and local party candidates to establish criminal governance regimes in most of Guerrero, attacks have been limited in the CRAC-PC region, as shown in the fourth column.

Anthropologists have long described indigenous peoples of the Tarahumara as highly mobile, moving bi-seasonally within the Sierra in order to maximize resources at the household’s various agricultural residences (Reference Graham, Cameron and TomkaGraham 1993). Communities in eastern Guerrero, in contrast, have been seen as largely sedentary, very much in the tradition of Mesoamerican indigenous peoples. In recent years, however, the regions have become more similar in terms of mobility. Recent census information reveals that, on average, 2.06 percent of inhabitants in the Tarahumara reported living in another state or abroad in 2005; that same figure was 2.0 percent in the CRAC-PC region. Ethnographic research reports that due to their dependence on agriculture and the dwindling incomes that it has provided them in recent decades, indigenous peoples from both regions have migrated inside their respective states, to other states in Mexico, and abroad. In recent years, young indigenous men have migrated to rural commercial farms in Chihuahua to harvest apples seasonally, as well as to urban areas. For decades indigenous men and women from the Montaña have migrated to other parts of Guerrero during corn harvests and to Sinaloa and Morelos to harvest other crops (Reference CanabalCanabal 2008).

External Validity

Is the history of indigenous mobilization, by which indigenous movements were able to scale up village-level customary laws and traditions into the creation of powerful regional autonomy regimes, a Guerrero-specific phenomenon?

Table 3 presents evidence of the joint effect of indigenous mobilization and local ethnic autonomy institutions as deterrents of narco violence in 881 indigenous municipalities in Mexico. Although this is not a measure of criminal governance, different studies suggest that narco rule is more likely to emerge in places where protracted wars lead narcos to seek to establish criminal governance regimes (Reference BlumeBlume 2017; Reference Trejo and LeyTrejo and Ley forthcoming). The dependent variable is the cumulative murders in conflicts associated with drug cartels for the 2007–2012 period. The key explanatory variables are history of mobilization, a cumulative count of indigenous protest events for the 1975–2000 period, when Mexico experienced a major cycle of indigenous mobilization; and ethnic autonomy institutions, a dichotomous variable of de jure (as in Oaxaca) or de facto (as in Chiapas and Guerrero) ethnic autonomy institutions for the 1994–2000 period, when indigenous peoples developed a wide variety of local ethnic arrangements. We control for relevant factors from the criminal violence literatures (see the online appendix).

Table 3 The impact of indigenous mobilization and ethnic autonomy on inter-cartel violence in Mexico, 2007–2012 (negative binomial model).

Robust standard errors, clustered by state, in brackets.

*** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, * p < 0.10.

Consistent with our narrative, the results show that the joint effect of mobilization and ethnic autonomy institutions (mobilization × ethnic autonomy) functioned as an important deterrent of narco violence in indigenous municipalities. Ethnic autonomy institutions had no discernible individual effect on criminal violence, and indigenous mobilization in the absence of ethnic autonomy institutions was associated with more narco violence. These results show that the deterrent effect of both indigenous customary laws and traditions and of social mobilization happen when social movements scale up local indigenous institutions to the regional level, and that this effect may be prevalent beyond the eastern Guerrero highlands.

Criminal Governance: Differing Experiences of Narco Rule

La Sierra Tarahumara (Chihuahua): Narco rule

For much of the 1980s and 1990s drug cultivation and trafficking in Chihuahua was under the control of the Juárez Cartel. But after the PRI (Partido Revolucionario Institucional) lost the state gubernatorial power in 1992, and the Juárez Cartel temporarily lost the informal state protection it had previously enjoyed under one-party rule (Reference Trejo and LeyTrejo and Ley 2018), rival cartels from neighboring states, particularly the Sinaloa Cartel, seized this opportunity to contest Juárez’s hegemony, leading the state into a protracted turf war. To fight this war, the Juárez Cartel created its own private militia, La Línea, and the Sinaloans subcontracted a number of local gangs and armed groups, including Artistas Asesinos, the Mexicles, Nueva Generación, and Los Salazar (Reference GuerreroGuerrero 2012).

Intercartel conflict over control of Ciudad Juárez and surrounding areas and the Sierra Tarahumara became particularly intense after the 2007 federal deployment of the army, when drug violence spiked tenfold in the following three years. A comprehensive federal intervention in Juárez, combining military presence, police reform, and social programs, dealt a severe blow to the Juárez Cartel, and the shifting balance of power allowed the Sinaloans to temporarily take control over the state’s drug production and trafficking industry by 2012. However, the 2014 arrests of Joaquín Guzmán, the Sinaloans’ boss, and Vicente Carrillo Fuentes, Juárez’s boss, led to bitter internal fragmentation marked by a new cycle of turf wars, particularly over the control of the Sierra Tarahumara.

As the turf wars became increasingly intense, breakaway OCGs sought to dominate communities, local governments, and territories in the Tarahumara. Los Salazar succeeded in taking control over several Low Sierra municipalities, and La Línea and Nueva Generación continued to fight for control over the High Sierra municipalities. Focusing on the municipalities where our interviewees work, Figure 2 identifies those municipalities where Trejo and Ley (Reference Trejo and Leyforthcoming) and the investigative journalistic accounts by Breach (Reference Breach2016 and Reference Breach2017a) and Mayorga (Reference Mayorga2016) provide strong evidence that cartels and their criminal associates have infiltrated the political process (by murdering municipal authorities and local party candidates, forcing party candidates to step down or forcing the parties to put cartel affiliates up for election); and infiltrated and taken control over municipal police. These two dimensions capture key features of narco conquest.Footnote 2 Detailed information from our anonymous interviews allows us to present a more comprehensive qualitative description of the mechanics of criminal governance.

Figure 2 Criminal governance in selected municipalities of the low and high Tarahumara, Chihuahua, 2014–2016.

Note: Criminal governance refers to those municipalities where there is strong evidence that cartels have infiltrated the political-electoral process and taken control over the municipal police.

Source: Breach (Reference Breach2016, Reference Breach2017a) and Trejo and Ley (Reference Trejo and Leyforthcoming).

OCGs in the Tarahumara resorted to targeted lethal attacks against mayors and local party candidates to gain de facto control over municipal governments. Between 2007 and 2014, 44 percent of Sierra municipalities experienced at least one attack against elected officials or candidates (Reference Trejo and LeyTrejo and Ley forthcoming). As Breach (Reference Breach2016) reported, in the 2016 election cycle Los Salazar were able to force resignations and/or impose candidates of their choice in 55 percent of the municipalities of the Low Sierra. Through assassination or infiltration, OCGs were able to take control over key local government positions. As Breach (Reference Breach2017a) describes, based on a military intelligence report, in 44 percent of the Sierra municipalities OCGs imposed the municipal security deputy of their choice and took control over the municipal police.

Control over the legal and illegal means of violence has enabled OCGs to dominate local economies. As Mayorga (Reference Mayorga2016) reports, in the High Sierra La Línea has engaged in an open forced recruitment strategy, kidnapping indigenous teenagers to work for them. A civil society leader anonymously confided to us that “OCGs recruit young indigenous men from a very early age for the sowing, harvesting, and trafficking of opium poppy.” Local indigenous leaders who opposed forced recruitment have paid with their lives. As Mayorga told us, “Irineo, a leader from Guadalupe y Calvo, who worked to empower local communities to resist the forced recruitment of children and teenagers, was murdered.”

OCGs have also displaced populations and rule directly over territories. As Breach reports (Reference Breach2017b), Los Salazar have engaged in major forced displacement of rural indigenous households in the Low Sierra. Those who attempted to oppose them suffered dire consequences. Two activists we interviewed who had had the temerity to document cartel abuses in Uruachi (Low Sierra) received death threats and had to ask for precautionary measures (medidas cautelares) from the Inter-American Human Rights Commission.

OCGs have come to control the movement of people and information in the Sierra. Across the Tarahumara, drug traffickers have installed armed checkpoints that control all kinds of transit. Many individuals have gone missing at these checkpoints, and few dare travel at night. Drug traffickers keep tight controls on information. The leader of the Sinaloa Cartel in Guadalupe y Calvo set up a public Wi-Fi network, and information exchanged through it could be easily intercepted (Proceso 2017). The cartels’ need to control information has also led them to target journalists. Miroslava Breach, the reporter we have cited as the main source of information on Los Salazar, was tragically murdered in March 2017, and Patricia Mayorga, the other major reporter in the region and one of our interviewees, went into exile a few weeks later.

People in the Tarahumara have been silenced. As a civil society leader shared: “People don’t want to talk about the violence occurring in their communities, because there is always someone watching or listening in the meetings.”

La Montaña/Costa Chica (Guerrero): Community rule

For much of the 1990s and the early 2000s the drug production and trafficking industries in Guerrero were under the control of the Sinaloa Cartel and its private militia led by the Beltrán-Leyva brothers. After the PRI lost the state gubernatorial seat in 2005 and the Sinaloans temporarily lost access to the informal protection they had enjoyed from state authorities, the Gulf Cartel sent their powerful private militia, the Zetas, to dispute the Sinaloans’ control over Guerrero (Reference Trejo and LeyTrejo and Ley 2018). The state plunged into a major intercartel war that intensified after the 2007 federal intervention, when one of the Beltrán-Leyva brothers was arrested and another murdered. Suspicions that the Sinaloans facilitated Alfredo Beltrán-Leyva’s arrest led the Beltrán-Leyva Organization (BLO) to break from the Sinaloa Cartel; Arturo Beltrán-Leyva’s murder led to the fragmentation of the BLO. Many of the BLO local plaza chiefs created their own independent OCGs and engaged in fierce wars for control of Guerrero’s criminal underworld (Reference KyleKyle 2015).

Using coercive techniques similar to those used by cartels in the Tarahumara, BLO breakaway groups and other OCGs have established different degrees of subnational criminal governance in Guerrero. They first established territorial controls in impoverished neighborhoods in the state capital, Chilpancingo, and in Acapulco (Reference KyleKyle 2015). Beyond urban centers, OCGs fought to control the poppy pentagon, a major area for drug production and trafficking, as illustrated in Figure 3. In the Tierra Caliente region in the western part of Guerrero, La Familia, the dominant cartel of the neighboring state of Michoacán, and their successors the Knights Templar fought deadly wars for control of poppy production municipalities against former BLO organizations Los Rojos and Guerreros Unidos (GU). Los Rojos and GU embarked in major turf wars in northern and central Guerrero; GU prevailed in the north and Los Rojos in the center. From there, Los Rojos have tried to expand their reach in the municipalities of Tixtla and Chilapa, the gateway to the Montaña region, and have experienced major conflicts with Los Ardillos, a local OCG.

Figure 3 Municipalities under the CRAC-PC System and the poppy pentagon in Guerrero.

Although Montaña/Costa Chica is a coveted region for drug production and trafficking, none of the OCGs fighting fierce turf wars elsewhere in the state have been able to establish control over the eleven geographically contiguous municipalities identified in Figure 3 that are part of the CRAC-PC system. Despite continual attempts by Los Rojos and rival criminal groups to penetrate this region, the CRAC-PC keeps tight controls over its outer borders. Although a government official and a party activist have been killed in the region (Reference Trejo and LeyTrejo and Ley forthcoming), the cartels have not capitalized on these murders to establish criminal governance regimes. Journalists have documented that some of the poorest indigenous households in the Montaña region have cultivated poppies for the cartels for decades (Reference Inzunza and PardoInzunza and Pardo 2016). Yet, as our interviewees noted, it is the communities—not the cartels—who dictate the terms of production. In other words, despite partial coexistence, communities have resisted and contained narcos operating in the region.

Societal Resistance to Narco Rule: The Indigenous Highlands of Guerrero

Developing regional ethnic autonomy institutions: The CRAC-PC

Responding to a major hike in homicides and sexual assaults, politicized communities from Malinaltepec (Montaña) and San Luis Acatlán (Costa Chica/Montaña) launched an ambitious community police project, the PC, in 1995. Drawing on indigenous customary laws and traditions from Mixteco, Tlapaneco, and Náhuatl communities and on the translocal networks built over a decade of mobilization, the PC is a police force providing security in one of Mexico’s most impoverished regions, where state institutions were either absent or colluded with local criminal groups.

Elected by community assemblies, members of the PC serve for two-year terms as village police. Building on translocal social movement ties, these village-level police forces are connected into a regional community police network headed by PC commanders, who are also elected by community assemblies. Since the PC’s inception, participation was conceived as community service linked to the community’s cargo system rather than as a professional activity. PC members receive no monetary compensation, though they have access to free housing and lodging. They are lightly armed with wooden rifles.

The PC was created as a parallel policing system that operates alongside the municipal police. Initially it handed criminals over to public prosecutors working through the formal justice system. But when PC members realized that public prosecutors were colluding with criminal groups, they took the radical step of developing a de facto parallel judicial system as well. Building on CAIN, the regional organization of community authorities promoted by the Catholic Church, PC leaders set up three regional Casas de Justicia (justice tribunals), with several local chapters, where commissioners elected by local communities through community assemblies serve as public prosecutors. After PC officers arrest an alleged criminal, they are taken to the Casa de Justicia, where commissioners initiate the investigation. The plaintiff is then handed over to the community assembly where the crime was committed. The assembly holds a public hearing and decides collectively whether the plaintiff is guilty and the severity of the charges. There is no jail time or solitary confinement. Following indigenous principles of justice and Catholic ideas of forgiveness and reconciliation, the assemblies seek to reintegrate criminals through community service and reeducation by the community elders. Criminals can spend anywhere from a few months up to eight years in this process, serving multiple communities in the region under strict local surveillance. In these judicial processes the Catholic-sponsored and internationally recognized Tlachinollan Human Rights Center of La Montaña serves as a key adviser to CRAC authorities.

Figure 4a and 4b show the Casa de Justicia of San Luis Acatlán, where CRAC prosecutors operate, and PC police commanders.

Figure 4 (a) Casa de Justicia (CRAC) of San Luis Acatlán, Guerrero. Photo by Guillermo Trejo. (b) Community Police (PC) of San Luis Acatlán, Guerrero. Photo by Guillermo Trejo.

Resisting narco rule

Building on fieldwork information, Figure 5 outlines the internal and external mechanisms of control within the CRAC-PC system that insulate the system’s eleven municipalities from narco takeover. The figure illustrates how different village-level indigenous communal institutions (i.e., communal assemblies and communal cargo systems) create micro-motivations (incentives) for members of the community police (PC) and judges from the Casas de Justicia (CRAC) to serve their communities and not collude with the cartels. It also illustrates how translocal social networks built over decades of social mobilization created the external protection that keeps the cartels away from the eastern highlands of Guerrero and how this protection has served as a safeguard for the preservation of the internal communal controls.

Figure 5 Mechanisms of internal and external control of CRAC-PC system.

Effective selection

CRAC and PC personnel and their advisers believe that their members do not become corrupt because communal assemblies select respected individuals for their jobs. A CRAC commander expressed it thus: “As a community member you know who the good and bad guys are.” In fact, those who get selected to serve in the CRAC or the PC often have long histories of service.

Oversight and sanction

Even if a bad recruit is selected, the system does not become corrupt because, our interviewees suggest, CRAC and PC members are subject to multiple sources of oversight. “We [in the communities] have control over our own police,” a female former CRAC commander from San Luis Acatlán told us. A male CRAC commander spoke directly about corruption: “If you accept money [from the narcos] and engage in acts of corruption, you become a bad example. It becomes public knowledge, and if you are guilty you will be investigated, prosecuted, and assigned to reeducation.” Knowing that communal sanctions are effective and that there is little impunity in the system leads most PC members to reject the narcos’ corrupting power.

Shame and honor

Beyond instrumental motivations associated with community accountability, social shame and honor ingrained in the cargo system are powerful deterrents of corruption. As a Catholic priest from the region put it: “PC members think: If I become corrupt and get caught, I will face social shame.” And the flip side of shame is the honor bestowed for good community service and the pride that CRAC-PC members feel in being part of an institution that is diametrically different from state and municipal police forces and local public prosecutor offices. A PC commander stated plainly: “We are different from the municipal police.” One of his rank-and-file members added: “For them it is all about the money.” And a CRAC regional commander elaborated: “The municipal president of San Luis trusts the CRAC-PC more than his own police! They take bribes but we don’t. We don’t charge for our services and we work diligently.”

As Figure 5 illustrates, the combination of communal accountability mechanisms and mechanisms of individual self-restraint deters CRAC-PC members from accepting bribes from cartels or colluding with OCGs that seek to develop criminal markets and establish criminal governance in the Montaña/Costa Chica region.

Beyond the individual behavior of the CRAC-PC members, external mechanisms associated with a history of social mobilization and the development of translocal networks facilitate the deflection of narco rule and the maintenance of territorial control over the eleven contiguous municipalities of the Montaña/Costa Chica region under CRAC-PC control.

Trust and information sharing

CRAC-PC policing power is the result of high levels of trust, which in turn result from an effective social selection of CRAC-PC members and the community’s permanent oversight. As an influential cleric from the Acapulco Archdiocese told us, “Communities support the PC because they trust them; and this support is their main source of power.” A regional PC commander summed it up well: “The PC’s most powerful weapon is the people’s support; we don’t need high-caliber weapons.” Trust leads villagers to denounce crime to CRAC-PC regional authorities and to cooperate and share information with them.

Cross-regional solidarity

When communities come together into regional translocal policing forces, their power multiplies. As a PC commander explained to us, “whenever there is a threat, members of neighboring PC units come to help; within a few minutes, you have all these PC patrols around the village. The people’s support empowers us.” These translocal networks of trust and solidarity allow the CRAC-PC to resist and contain the narcos. Not only do CRAC-PC commanders have access to firsthand information from every village and know who gets in and out of their territory, but they also have access to manpower to confront external encroachment. These external mechanisms empower the CRAC-PC system to keep tight border controls of their territory and to enjoy the strength in numbers that deters the cartels from launching a major attack to conquer the Montaña/Costa Chica region.

Beyond their own members, the CRAC-PC system has also succeeded in preventing the cartels from recruiting young indigenous men into their ranks and from forcing indigenous households to cultivate poppies for them, as they have done in the Tarahumara.

As Figure 6 illustrates, the same mix of societal accountability and self-restraint mechanisms that deter community police and prosecutors from colluding prevents young indigenous males from becoming drug traffickers or foot soldiers. A parish priest from the region confided: “I often hear young men warn their friends, ‘Behave, otherwise the CRAC-PC will get you.’” A regional PC commander effectively captured the mix of deterrence and shame: “Young men know that if they get involved in something bad, they will not go very far. They will get caught, face trial, and undergo reeducation through community work.”

Figure 6 Mechanisms of community control under CRAC-PC system.

Although cartels have displaced entire populations or taken over their lands to cultivate poppies in other parts of Guerrero and in the Tarahumara, in the Montaña/Costa Chica they may buy poppies from poor rural indigenous households but do not control production or rule over communities. As one PC commander expressed to us: in the most remote and impoverished areas of the Montaña villagers supplement their practice of subsistence agriculture with poppy cultivation. “It is a survival strategy,” he said. But communal shame and the prospect of having to undergo reeducation with the elders induce self-restraint: Families do not completely abandon corn and replace it with poppies; when a family member tries to strike a more ambitious deal with the narcos, they hold him back. “Once a woman brought her son for reeducation, because he was getting too close to the narcos,” a PC commander noted.

Challenges to CRAC-PC governance

Despite the CRAC-PC’s ability to contain the narcos, we can identify two challenges to the system: internal political divisions and human rights violations.

Between 2013 and 2015 the CRAC-PC experienced a damaging internal fissure when a group of external advisers, in close collaboration with the state governor, led a few communities to withdraw from the system to create an alternative communal police force. OCGs took advantage of internal conflicts to make inroads into the region (Reference Grecko and EspinoGrecko and Espino 2015) but did not achieve a permanent presence. After the CRAC-PC resolved this internal rift, the system was able to contain the narcos again in the eleven municipalities under analysis.

In municipalities that recently joined the CRAC-PC system,Footnote 3 where indigenous institutions and customary practices are weak and commanders’ actions may be less accountable than in the eleven original CRAC-PC municipalities, concerns have been raised about human rights violations (CNDH 2016). While there is no evidence of generalized internal violations, any internal abuse could threaten the system from within.

Failing to Resist Narco Rule: The New Conquest of the Sierra Tarahumara

Whereas indigenous communities from eastern Guerrero have contained the narcos, communities in the Tarahumara have been unable to resist. Using the case of the communities under the CRAC-PC system as a counterfactual, we illustrate how the failure of Tarahumara communities to scale up and reinvent local practices into regional autonomy regimes prevented indigenous communities from resisting narco conquest.

Strong local traditions without translocal networks

As in the mayordomía, or civil-religious system, of central and southern Mexico, communal authority structures in the Sierra Tarahumara fuse political-civil and ritual-religious offices (cargos). Typically, these offices are unpaid and are assumed to be the responsibility of respected community members. While traditional authority figures among the Rarámuri tend to be exhortative rather than authoritative, given the emphasis placed on individual and family autonomy, figures such as the unofficial indigenous governor are pivotal in traditional systems throughout the Sierra.Footnote 4 Indigenous governors preside over several villages and, like PC commanders, are elected by community assemblies in which all adult residents participate (Reference Vinicio and GotésVinicio 2012).

Maintaining community harmony is a central function of indigenous authorities in the Sierra Tarahumara. Communities name a police commissioner who serves as a broker to municipal authorities and during annual fiestas communities elect community members to carry out policing functions. Those who commit wrongdoing are brought before local indigenous judges, who hear their cases and make decisions about culpability and punishment based on indigenous customary laws. These judges deal exclusively with civil conflicts and infractions, not criminal or penal ones: the latter are brought before public prosecutors from the state judicial system. Community hearings are open to public scrutiny and participation. As in the Guerrero highlands, the emphasis within Rarámuri communities is on reeducation and reparation (Reference Vinicio and GotésVinicio 2012).

Despite the similarities in the village-level community organization in the indigenous highlands of Chihuahua and Guerrero, the key difference between these regions is the translocal network of mobilization that served as the societal infrastructure to scale up local communal practices to develop the CRAC-PC regional system. In the absence of these translocal networks and institutions, communities in the Tarahumara were unable to resist narco conquest.

Unequipped to resist

Inadequate selection

State and municipal police forces are in charge of policing the Sierra. Even though these are predominantly indigenous regions, community assemblies and traditional authorities have no jurisdiction over these mestizo police forces and are therefore unable to participate in police recruitment as they do in the Guerrero eastern highlands. In nearly one-half of the Sierra municipal police forces, the narcos select or impose their own personnel (Reference BreachBreach 2017a) and those who remain independent cannot enforce the law. Strikingly, the entire municipal police force of Guadalupe y Calvo deserted after receiving threats from organized crime (Animal Político 2012).

Weak oversight

Given the lack of trust in official police, cartels are free to target traditional community authorities, and oversight disappears. The cartels have killed several Rarámuri governors, and the regular attacks on traditional leaders, combined with the takeover of many indigenous communities, have effectively shut down the administration of indigenous local justice in some regions. Examples abound. A former indigenous governor and his family from Uruachi were attacked by organized crime and are now under precautionary measures from the Inter-American Human Rights Commission. In 2016 an armed group stole a list of indigenous governors in Urique and Guazapares and began to threaten them, one by one (Reference MayorgaMayorga 2016).

Low levels of cohesion and self-esteem

The growing vulnerability of traditional authorities, together with the difficulty of communication within the Sierra due to high levels of violence, has, in some areas, reduced the frequency of community meetings that used to unite several villages. One indigenous leader put it quite simply: “We can’t meet and can no longer do anything. Our traditions (rituales) are broken” (Reference MayorgaMayorga 2016). An NGO advisor in Coreachi told us that there is still a sense of community there, but authorities are not able to meet anymore and the system of juicios has ceased to function. “Although customary laws and traditions are still present, they are under severe stress.”

One result of this breakdown of community control is a severe lack of cohesion among the Rarámuri. The pride that CRAC-PC members take in their organizational cohesion and collective accomplishments is not present in the Tarahumara. Instead, advisors speak of low self-esteem among indigenous communities. The stories we heard were not of pride and a sense of authorship but of nostalgia filled with a sense of progressive loss and cultural annihilation. This has created a vicious circle that weakens community bonds and villagers’ ability to confront the narcos. The social control that Rarámuri governors formerly exercised has weakened considerably in recent years. One NGO advisor with decades of work in Guadalupe y Calvo told us that elders “lost control of their young people many years ago.” A social worker suggested that this is particularly evident in the Low Sierra, where “[traditional] justice systems do not function much” and “young people have not even seen [traditional] ceremonies.”

Lack of self-restraint

In the absence of community control and subsequent lack of cohesion, it is very difficult to control drug production and consumption. For decades indigenous peoples in the Sierra, much like their counterparts in eastern Guerrero, cultivated marijuana and poppies to supplement their meager incomes. Indigenous peasants negotiated the terms of this arrangement in a context where cartels were present but did not control the area. However, over the last decade, as traditional systems of social control have eroded and in some places disappeared completely, self-restraint has eroded. NGO activists working in the Low Sierra told us that when young drug consumers are unable to pay with cash, they pay either with drugs they cultivate in their fields or with their labor.

No strength in numbers

Although Tarahumara communities name a police commissioner and elect community members to police their villages during the annual fiestas, they have not developed a comprehensive regional community policing system like the PC in eastern Guerrero. With access only to a corrupt or poorly equipped municipal police, they are very much at the mercy of the cartels. The absence of translocal network connections leaves them without the regional bonds of solidarity and information sharing that allow communities under the CRAC-PC system to resist and contain the narcos.

Conclusion

We have argued that while village-level indigenous customary laws and traditions can be invaluable institutional instruments for the provision of public goods, they are insufficient to resist narco conquest in Mexico. As our paired comparison of indigenous communities in Guerrero and Chihuahua suggests, the institutional articulation of local indigenous customary laws and traditions into regional autonomy regimes—the result of decades of indigenous mobilization—is the decisive factor differentiating between conquest and effective resistance. By scaling up local indigenous communal practices of collective decision-making, participation, and societal accountability into a powerful regional policing and justice system, indigenous communities and movements and their Catholic and secular leftist allies in eastern Guerrero have developed the social infrastructure for resistance against drug cartels.

At a macro level, our findings show that social movements and their allies can play a crucial role in scaling up effective practices of communal indigenous governance to the regional level, where the provision of public security is more relevant. As Tarrow suggests (Reference Tarrow, Givan, Roberts and Soule2010), the scaling up of successful grassroots organizational practices requires effective coordination, brokerage, and reimagining of how group boundaries get altered. The CRAC-PC experience reveals that the dialogue between indigenous communities and their Catholic and leftist allies was crucial in transforming local indigenous customary laws and traditions into powerful regional ethnic institutions. As we see from juxtaposing the experience of the CRAC-PC with the narco conquest of the Tarahumara, this political process of scaling up has not only contributed to developing a comparatively peaceful social order but has also facilitated the cultural survival of local indigenous customary laws and traditions.

At a micro level, the experience of the CRAC-PC system shows that when communities select community members to serve as police agents and play an active role in permanently keeping them accountable, the need for professionalization, material compensation, and weaponry becomes secondary. The CRAC-PC experience also shows that policing cannot be divorced from judicial practices. Policing is more effective when communities play a central role in selecting local public prosecutors and in keeping them accountable to the citizenry. Most importantly, the CRAC-PC experience suggests that communities cannot delegate policing and prosecutorial practices to professionals; if peace is to be achieved and preserved, communities should be at the front and center of policing and judicial institutions and practices.

Additional File

The additional file for this article can be found as follows:

• ONLINE APPENDIX. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.377.s1

Acknowledgements

We presented this work at several venues and received valuable feedback from so many at LASA 2016 and 2017, Brown University in April 2017, Kellogg Institute for International Studies at the University of Notre Dame in September 2017, and APSA 2018. Special thanks to Richard Snyder, Agustina Giraudy, Eduardo Moncada, Peter Andreas, LARR editor Aníbal Pérez-Liñán, and three anonymous reviewers for their invaluable feedback. We are deeply appreciative of those who took the time to talk with us and share their experiences in Guerrero and in Chihuahua. Josh Patton’s assistance in laying the groundwork for our fieldwork in Chihuahua proved to be an enormous resource. Marco Vinicio offered guidance on the Sierra Tarahumara in early stages of the project and Fr. Jesús Mendoza and Fr. Leonardo Morales facilitated our fieldwork in Guerrero, for which we are grateful.