No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 September 2022

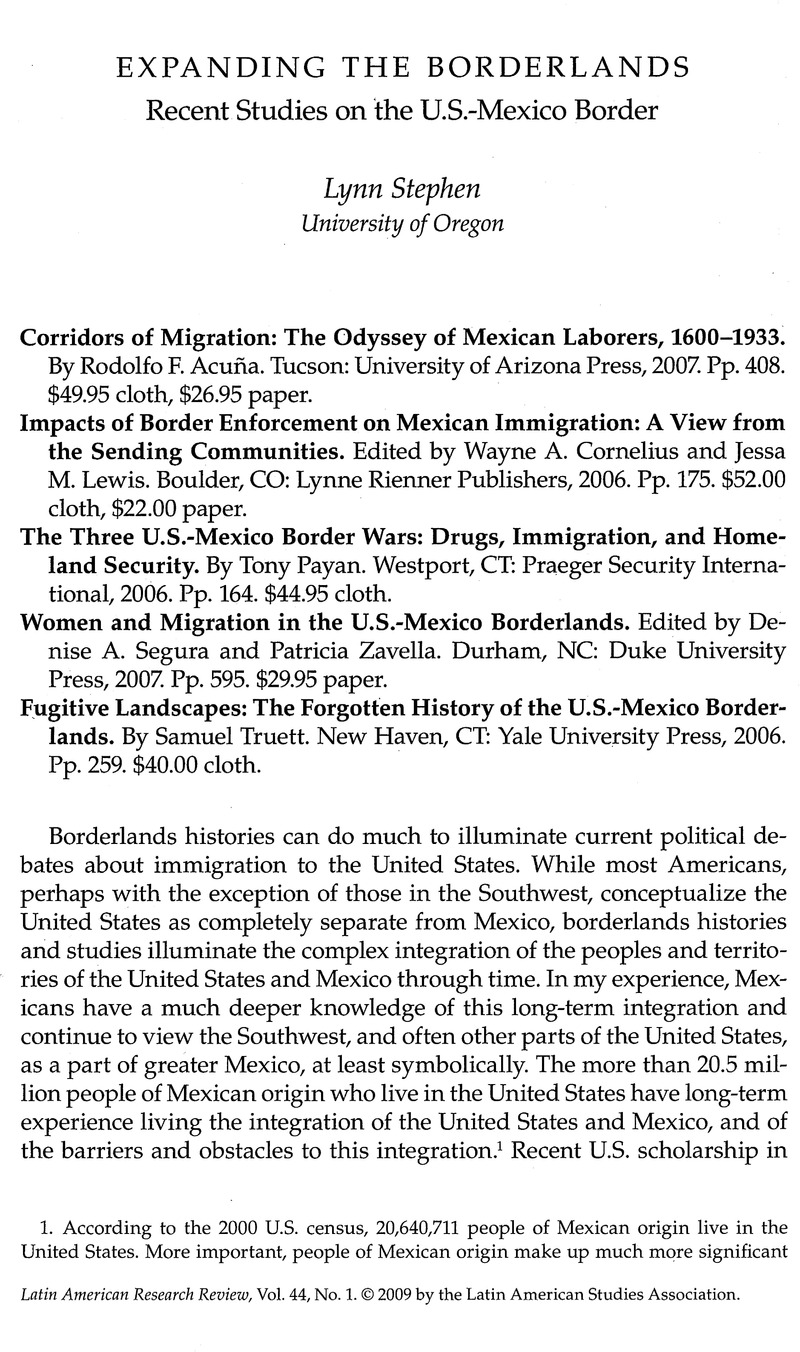

1. According to the 2000 U.S. census, 20,640,711 people of Mexican origin live in the United States. More important, people of Mexican origin make up much more significant percentages of state populations: 41 percent in California and 24 percent in Texas. These statistics are from a map prepared by the Center for Latin American, Caribbean, and Latino Studies at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York based on the 2000 census (http://web.gc.cuny.edu/lastudies/Mexican%20Population%20by%20State,%201argest%20concentrations.pdf). The U.S. population at the time was 280,421,906, making people of Mexican origin roughly 7.3 percent of the total U.S. population. See “Population by Race and Hispanic Origin for the United States: 2000,” an online table provided by the U.S. Census Bureau (http://www.census.gov/prod/2001pubs/cenbr01-l.pdf).

2. See Michael Kearney, “The Effects of Transnational Culture, Economy, and Migration on Mixtec Identity in Oaxacalifornia,” in The Bubbling Cauldron: Race, Ethnicity, and the Urban Crisis, Michael Peter Smith and Joe R. Feagin, eds. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995), 226–243; “The Local and the Global: The Anthropology of Globalization and Transnationalism,” Annual Review of Anthropology 24 (1995): 547–565; “Transnationalism in California and Mexico at the End of Empire,” in Border Identities: Nation and State at International Frontiers, ed. Thomas W. Wilson and Hastings Connan (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 117–141; “Transnational Oaxaca Indigenous Identity: The Case of Mixtecs and Zapotees,” Identities 7, no. 2 (2000): 173–195. More recent examples building on the work of Kearney and others include Nicholas De Genova, Working the Boundaries: Race, Space, and “Illegality” in Mexican Chicago (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005) and Robert Smith, Mexican New York: Transnational Lives of New Immigrants (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005).

3. I prefer the term transborder to transnational, as most processes of Mexican migration and immigration historically involve the crossing of ethnic, cultural, colonial, and state borders, as well as the U.S. and Mexican national borders. Migrants and immigrants also cross regional borders within the United States that are often different from those in Mexico but may overlap with those of Mexico—for example, by reproducing the racial-ethnic hierarchy of Mexico, which lives on in many Mexican communities in the United States, usually relegating people of indigenous and African descent to the bottom of the hierarchy. The transnational thus becomes a subset of the transborder, one of many borders that Mexican migrants and immigrants cross and recross.

4. See Lynn Stephen, Transborder Lives: Indigenous Oaxacans in Mexico, California, and Oregon (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007); Laura Velasco, Mixtec Transnational Identity (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2005); Jonathan Fox and Gaspar Rivers, eds., Indigenous Mexican Migrants in the United States (La Jolla: Center for U.S. Mexican Studies and the Center for Comparative Immigration Studies, University of California, San Diego, 2004); Jennifer Hirsch, A Courtship after Marriage: Sexuality and Love in Mexican Transnational Families (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003); and Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo, Doméstica: Immigrant Workers and Caring in the Shadows of Affluence (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001).

5. For example, John A. Adams Jr., Bordering the Future: The Impact of Mexico on the United States (London: Praeger, 2006), argues that Mexico's economic and industrial expansion, population growth, energy needs, political trajectories, and strategic location will continue to be of tremendous importance to the United States. He describes the border as “a window on the future of binational relations and interdependence” linked to issues such as agricultural production, infrastructure enhancements, air quality, and water rights (124). Using the border as a lens for broader issues of U.S.-Mexico integration, Adams argues as a businessman that the United States has much to value in its neighbor, Mexico.

6. The Chicana lesbian, feminist, poet, and intellectual Gloria Anzaldúa has had widespread influence on the way that the concept of borderlands is understood. Her concept, set forth in Borderlands = La frontera (San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1999), includes both the geographical space around the U.S.-Mexico border and a metaphorical space that accompanies subjects to any location. Borderlands are where people “cope with social inequalities based on racial, gender, class, and/or sexual differences, as well as with spiritual transformation and psychic processes of exclusion and identification—of feeling ‘in between’ cultures, languages, or places. And borderlands are spaces where the marginalized voice their identities and resistance. All of these social, political, spiritual, and emotional transitional transcend geopolitical space” (Segura and Zavella 4).

7. For a detailed look at the case of a corrupt border official working in Tijuana with a smuggling ring, see Ken Ellingwood, Hard Line: Life and Death on the U.S.-Mexico Border (New York: Random House, 2004), 87–88. In May 2008, the New York Times and Frontline teamed up to produce the Web site, television show, and interview series Mexico: Crimes at the Border, which featured the cases of eight corrupt U.S. customs officers and border officials (http://www.pbs.org/frontlineworld/stories/mexico704/history/gatekeepers.html).

8. For a discussion of labor conditions, see Ernesto Galarza, Merchants of Labor: The Mexican Bracero Story (Santa Barbara, CA: McNally and Lofton, 1962). Douglas Massey, “March of Folly: U.S. Immigration Policy after NAFTA,” American Prospect 37 (1997): 1–16, emphasizes the role of workers legalized through IRCA and SAW in attracting undocumented immigrants, who rely on the social networks of legal residents to facilitate their employment, housing, and other needs in the United States. See also Phillip Martin, Promise Unfulfilled: Unions, Immigration, and the Farm Workers (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2003), and Wayne Cornelius, “Controlling ‘Unwanted’ Immigration: Lessons from the United States, 1993–2004,” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 31, no. 4 (2005): 775–794.

9. Such trends resonate with findings from other parts of Mexico where participation in the bracero program and IRCA also brought significant numbers of people legal residency. For a discussion of Zapotec and Mixtec indigenous migration trends linked to these same two policies, see Stephen, Transborder Lives, 94–132.

10. My own research on the disappeared—those who cross the border and never appear dead or alive—suggests that these numbers are likely even higher. Every community with a migration history also has histories of the disappeared. See Lynn Stephen, “Los Nuevos Desaparecidos: Immigration, Militarization, Death, and Disappearance on Mexico's Borders,” in Security Disarmed: Critical Perspectives on Gender, Race, and Militarization, ed. Barbara Sutton, Sandra Morgen, and Julie Novkov (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2008), 122–158.

11. The probability of returning from the United States among undocumented Oaxacan migrants went from a high of 20 percent in 1982 to a low of 5 percent in 2004, according to Wayne A. Cornelius, Scott Borger, Adam Sawyer, David Keyes, Claire Appleby, Kristen Parks, Gabriel Lozada, and Jonathan Hicken, “Controlling Unauthorized Immigration from Mexico: The Failure of ‘Prevention through Deterrence’ and the Need for Comprehensive Reform” (La Jolla: Center for Comparative Immigration Studies, University of California, San Diego, 2008), 8. For the cost of passage, see pages 5–6 at http://www.immigrationpolicy.org/images/File/misc/CCISbriefing061008.pdf.

12. See, e.g., Matthew Gutmann, Fixing Men: Sex, Birth Control and AIDS in Mexico (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007).