No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 October 2022

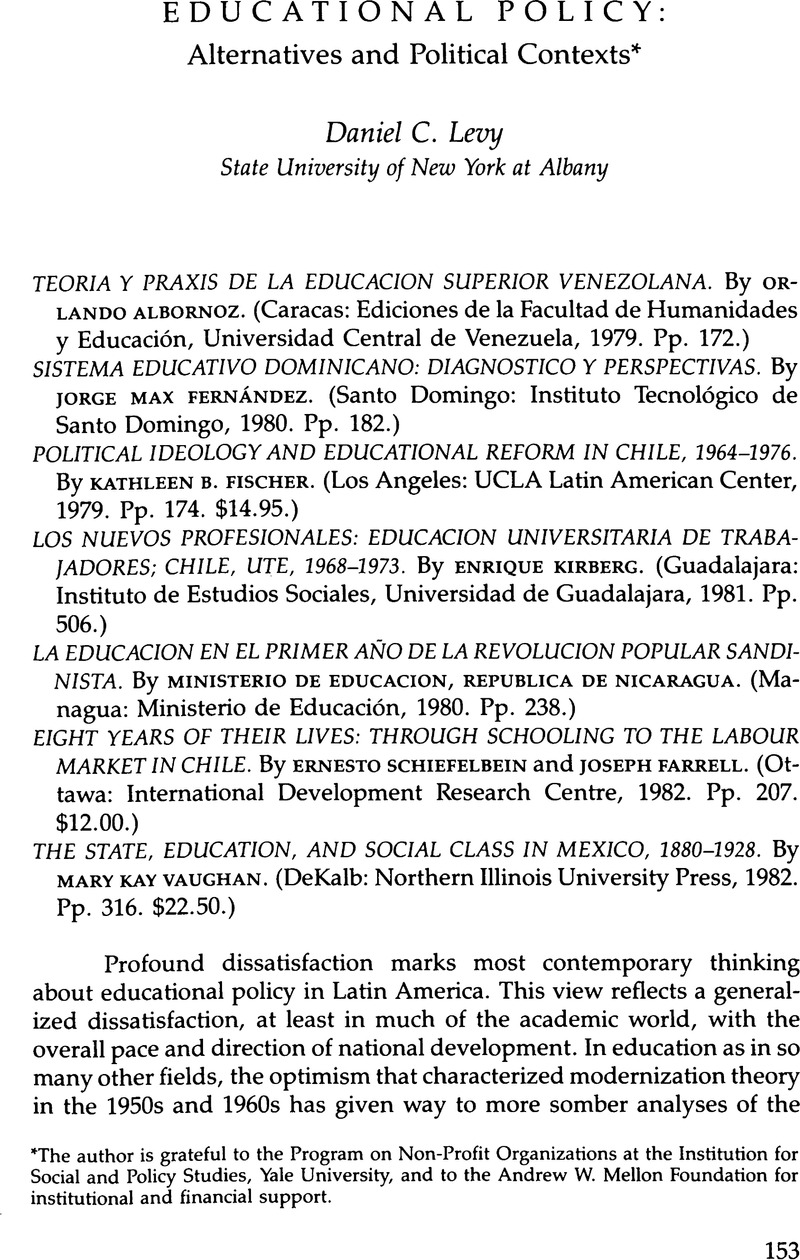

The author is grateful to the Program on Non-Profit Organizations at the Institution for Social and Policy Studies, Yale University, and to the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for institutional and financial support.

1. For a useful overview of how some central debates between modernization and neo-Marxist thinkers play themselves out in the comparative education field, see, for example, Erwin H. Epstein, “Currents Left and Right: Ideology in Comparative Education,” Comparative Education Review 27, no. 1 (1983): 3–28; see also the ensuing commentaries on pp. 30–45. Literature on education and development began to take great strides in the 1960s. See, for example, Philip J. Foster, Education and Social Change in Ghana (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1965); and Education and Political Development, edited by James S. Coleman (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1965).

2. In general, the literature proposing practical policy alternatives needs to become more explicit in identifying the agents of change. Several works implicitly bet heavily on vague coalitions of progressive forces. In the works reviewed here, the principal agents appear to be: for the Nicaraguan publication, the revolution and its mass support (although with leadership); for Fernández, progressive policymakers energized by pressure groups; for Albornoz, responsible government officials standing up to pressure groups; for Kirberg, progressive students and others within the educational structure, backed by broad support beyond; for Schiefelbein and Farrell, planners and policymakers drawing on empirical research; for Fischer, a wide range of political processes, especially popular-democratic ones; for Vaughan, probably the activated masses, but her emphasis is on the lack of policy change.

3. See, for example, David Felix, “Income Distribution and the Quality of Life in Latin America: Patterns, Trends, and Policy Implications,” LARR 18, no. 2 (1983): 3–33.

4. See, for example, Richard R. Fagen, The Transformation of Political Culture in Cuba (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1969).

5. The authors of this work are circumspect almost to the point of silence on the intriguing question of exporting the Sandinista's revolutionary educational model.

6. There are at least two fine accounts of the educational policy alternatives attempted during Peru's restricted and aborted revolution, post-1968. See Robert Drysdale and Robert Myers, “Continuity and Change: Peruvian Education,” The Peruvian Experiment, edited by Abraham Lowenthal (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975), pp. 254–301; and Erwin H. Epstein, “Peasant Consciousness under Peruvian Military Rule,” Harvard Educational Review 52, no. 3 (1982): 280–300.

7. Two of the most prominent books cited on behalf of radical alternatives in Latin American educational policy are Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (New York: Seabury Press, 1974); and Iván Illich, La sociedad desescolarizada (Barcelona: Barrai Editores, 1974). Another notable source is Educational Alternatives in Latin America: Social Change and Social Stratification, edited by Thomas LaBelle (Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center Publications, 1975) or LaBelle's own Non-Formal Education and Social Change in Latin America (Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center Publications, 1976).

8. See, for example, Albornoz's Poder y liderazgo en la escuela primaria venezolana (Caracas: Societas, 1974).

9. I am thinking principally, but not exclusively, of working papers published by the Programa Interdisciplinario de Investigaciones en Educación and by FLASCO in Santiago.

10. For an elaboration of this point, see Karen L. Remmer, “Evaluating the Policy Impact of Military Regimes in Latin America,” LARR 13, no. 2 (1978): 39–54. I have tried, in several works on higher education, to explore the relation between policy and regime type; for example, “Comparing Authoritarian Regimes in Latin America: Insights from Higher Education Policy,” Comparative Politics 14, no. 1 (1981): 31–52.

11. Charles W. Anderson, “System and Strategy in Comparative Policy Analysis: A Plea for Contextual and Experimental Knowledge,” in Perspectives on Public Policy Making, edited by William Gwyn and George Edwards III (New Orleans: Tulane University Press, 1975), pp. 230–31.