No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

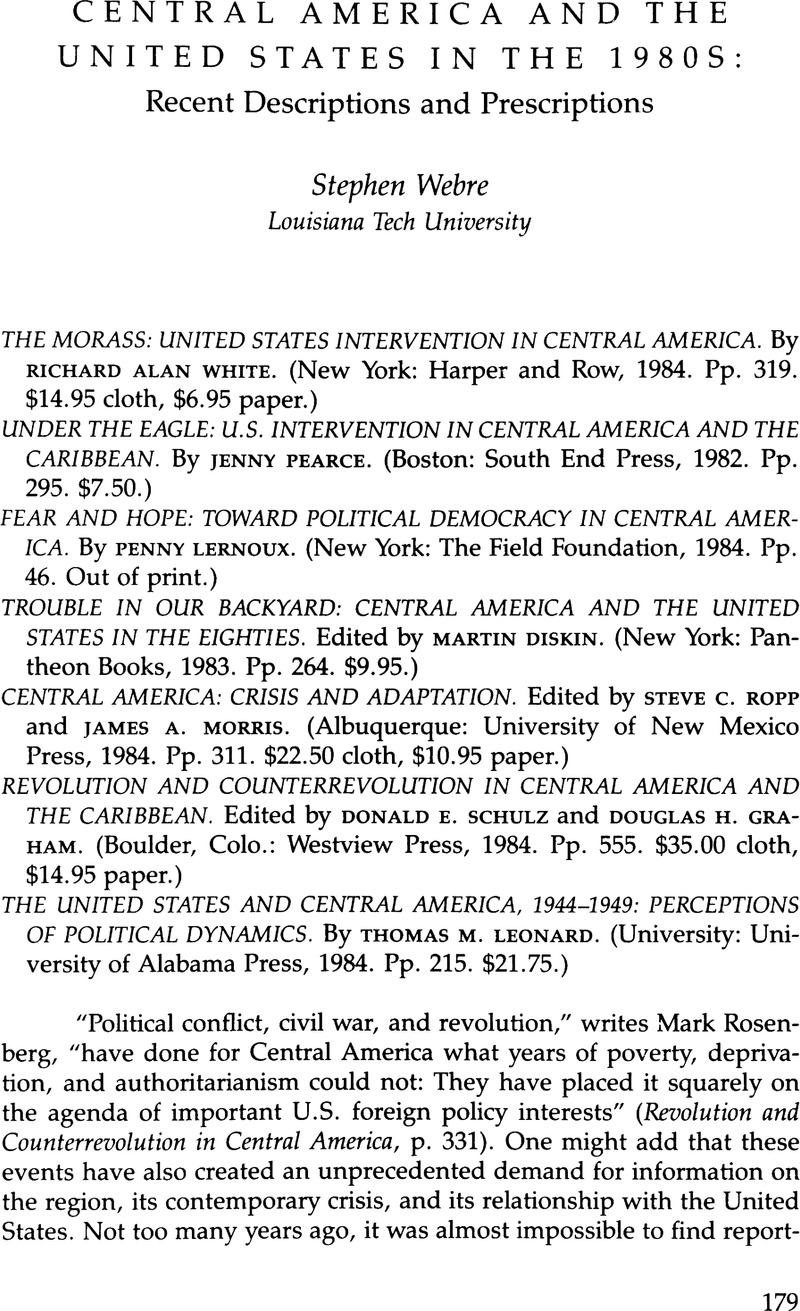

Central America and the United States in The 1980S: Recent Descriptions and Prescriptions

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1986 by the University of Texas Press

References

Notes

1. Walter LaFeber, Inevitable Revolutions: The United States in Central America, expanded ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, 1984); and Ralph Lee Woodward, Jr., Central America: A Nation Divided, 2d ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985).

2. In the text, White states simply that this form of repression “is almost totally directed at the working classes (86.5 percent of the victims) and particularly at the rural population, which makes up 75 percent of the dead” (p. 45). But in a tiny footnote to the accompanying table (p. 44), White concedes that these figures, obtained from the Archdiocese of San Salvador, represent only those cases left after the exclusion of all those whose occupation is either unknown or falls into “marginal categories such as merchants, journalists, etc.” The number of cases excluded from the count can in fact be quite high, reaching almost half (48.2 percent) for 1981 and almost three-fourths (72 percent) for 1982. The objection here is not that White is necessarily wrong about the role of the death squads and civilian massacres by regular troops—sadly, he is probably closer to the mark than not, and he is probably also correct when he speaks of the ultimate “ineffectiveness of this barbaric counter-insurgency tactic” (p. 45). My objection is that in playing games with the numbers, he is creating a false impression of precision that, once appreciated, wrests some force from his own skillful critique of the Reagan administration's misuse of figures to obscure the distribution of monies between economic and military assistance (pp. 233–39).

3. See “Dissent Paper on El Salvador and Central America,” a mimeographed paper circulated in late 1980 that allegedly originated among analysts in the State Department or the CIA or both; Piero Gleijeses, “The Case for Power Sharing in El Salvador,” Foreign Affairs 61 (Summer 1983):1048–63; and Donald E. Schulz, “Postscript: Toward a New Central American Policy,” in the Schulz and Graham volume reviewed here. Lernoux's Fear and Hope is already out of print.

4. There was a minor domestic flap over this issue during the 1984 presidential campaign. The CIA's controversial Nicaragua manual has since been published as Psychological Operations in Guerrilla Warfare, with essays by Joanne Omang and Aryeh Neier (New York: Vintage Books, 1985).

5. In addition to those reviewed here, other collaborative works include El Salvador: Central America in the New Cold War, edited by Marvin E. Gettleman, Patrick Lace-field, Louis Menashe, David Mermelstein, and Ronald Radosh (New York: Grove Press, 1981); Guatemala in Rebellion: Unfinished History, edited by Jonathan L. Fried and Marvin E. Gettleman (New York: Grove Press, 1983); Nicaragua in Revolution, edited by Thomas W. Walker (New York: Praeger, 1982); Central America: International Dimensions of the Crisis, edited by Richard E. Feinberg (New York: Holmes and Meier, 1982); Central America and the Western Alliance, edited by Joseph Cirincione (New York: Holmes and Meier, 1985). There are many others.

6. Enrique Baloyra, El Salvador in Transition (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1982).

7. J. C. Cambranes, Coffee and Peasants: The Origins of the Modern Plantation Economy in Guatemala, 1853–1897 (Stockholm: Institute of Latin American Studies, 1985). Two further volumes are to appear, bringing the story down to the present crisis.

8. Montgomery's chapter incorporates material from 1983 not to be found in her Revolution in El Salvador: Origins and Evolution (Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1982) but otherwise follows the book's general line of argument.

9. Hanratty's essay complements nicely the relevant essays in The Future of Central America: Policy Choices for the U.S. and Mexico, edited by Richard R. Fagen and Olga Pellicer (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1983).

10. Richard H. Immerman, The CIA in Guatemala: The Foreign Policy of Intervention (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1982); and Stephen Schlesinger and Stephen Kinzer, Bitter Fruit: The Untold Story of the American Coup in Guatemala (Garden City, N. Y: Doubleday, 1982).