Article contents

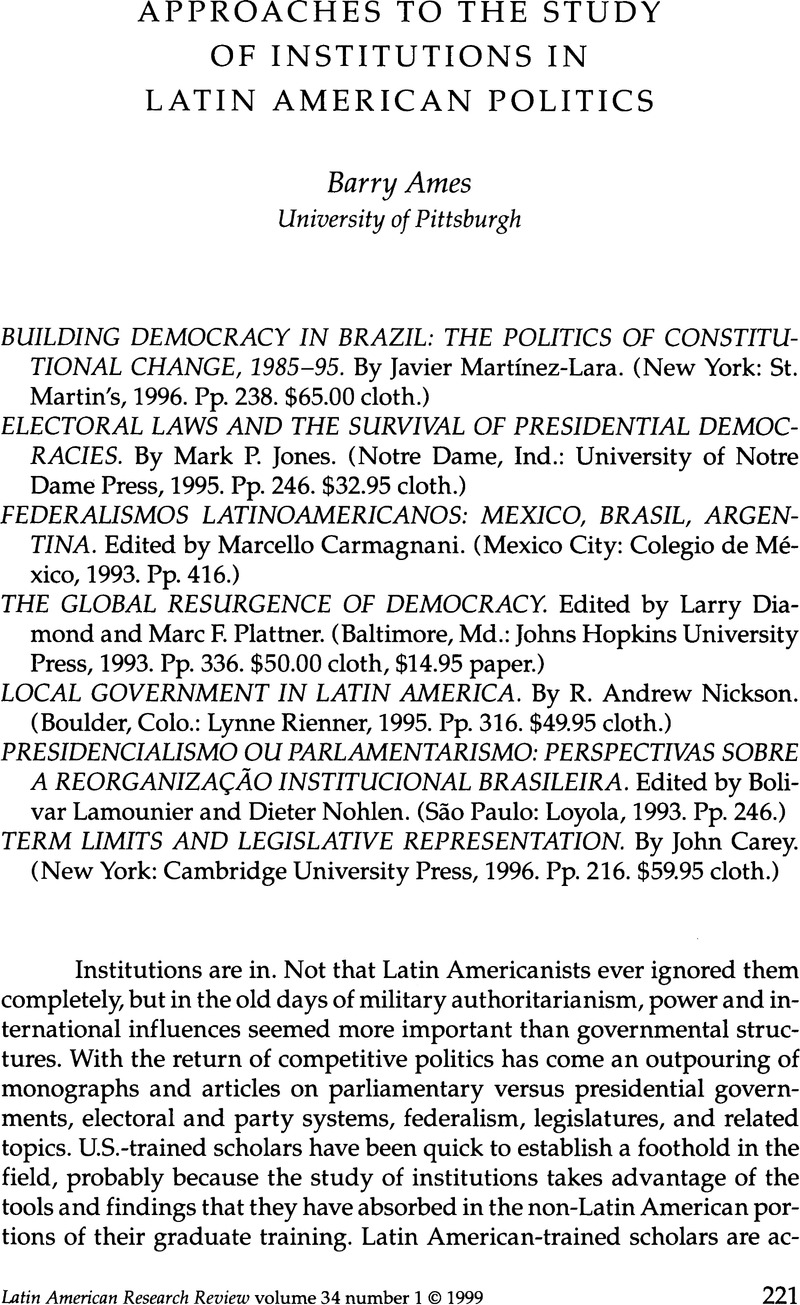

Approaches to the Study of Institutions in Latin American Politics

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1999 by the University of Texas Press

References

Notes

1. The works reviewed here are simply the latest batch of books on institutions received by LARR. Other recent and important works that are “institutional” in focus include Michael Coppedge, Strong Parties and Lame Ducks: Presidential Patriarchy and Factionalism in Venezuela (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1994); Barbara Geddes, Politicians Dilemma: Building State Capacity in Venezuela (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1996); Institutional Design in New Democracies, edited by Arend Lijphart and Carlos Waisman (Boulder, Colo.: Westview, 1996); The Failure of Presidential Democracy, edited by Juan Linz and Arturo Valenzuela (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994); Matthew Shugart and John Carey, Presidents and Assemblies: Constitutional Design and Electoral Dynamics (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992); and Presidential Institutions and Democratic Politics: Comparing Regional and National Contexts, edited by Kurt von Mettenheim (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996).

2. Diamond and Plattner range beyond Latin America to Africa, Asia, and Eastern Europe. I will treat only the material relevant to Latin America.

3. The formal members of Cardoso's coalition include only the Partido da Frente Liberal (PFL), the Partido Social Democrático Brasileiro (PSDB), and the Partido Trabalhista Brasileira (PTB), but I think the campaign alliance is a more appropriate yardstick.

4. I have found the same result in Brazil since 1988. Presidential success rates would look a lot worse if analysts included the nonbills, those bills that the president gave up on after congressional leaders said they would be “dead on arrival.”

5. Note that this problem would be only partially alleviated by comparing equivalent policy areas, such as tax policy, across countries.

6. Jones then makes a useful jump, one that other country-focused institutional studies would do well to emulate. He switches to the subnational level to examine the experience of Salta, an Argentine province in which the governor, bereft of a legislative majority, was unable to push through legislation crucial to the state's economic recovery.

7. Note, however, that Jones only has nineteen data points in this regression. Moreover, three are from Brazil and two are from Argentina. District magnitude within Argentina is related to multipartism, and this situation is true in Brazil as well. Jones admits that extreme outliers, especially in Uruguay, Nicaragua, and Venezuela, may obscure the relationship.

8. See Michael R. Kulisheck, “Placebo or Potent Medicine? Electoral Reform and Political Behavior in Venezuela.” Paper presented at the conference “Compromised Legitimacy? Assessing the Crisis of Democracy in Venezuela,” held in Caracas, 9–10 May 1996. Kulisheck found that patterns of floor attendance and floor speaking did not differ between the two types of deputies (that is, the district deputies were not seeking to “advertise” themselves to their constituents). He did find, however, that the number of parties in pre-election coalitions was sizably larger in district elections than in list elections.

9. It happens that most deputies do not end up with administrative jobs, and it is unclear whether most deputies really want such jobs. Whether all those who want jobs get them, or whether those who please party leaders get them, are questions left to future researchers.

10. See especially the work of Barry Weingast, “The Economic Role of Political Institutions: Market-Preserving Federalism and Economic Development,” Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 11, no. 1 (Apr. 1995):1@-31.

11. Anthony Leeds, “Brazilian Careers and Social Structure: A Case History and Model,” in Contemporary Cultures and Societies of Latin America, edited by Dwight Heath and Richard Adams (New York: Random House, 1965), 379–401.

12. Modeled after the Eurobarometer, the Latinbarometer covers nearly every country in Latin America. For 1996, Latinbarometer involved over eighteen thousand interviews in seventeen countries. Funding for the surveys came from the European Union (via the Centro de Investigación, Promoción y Cooperación Internacional in Spain) and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP). The Latinbarometer Corporation, which controls the data, sells marginal percentages and cross-tabulations, but it has not released the raw data to the academic community at large. Given the Latinbarometer's international funding and current norms in the United States regarding data sharing, this practice is clearly unacceptable.

13. The example that Nohlen gives is instructive: it is easy to prove that the fluidity of the electoral system depends to a high degree on the system of party politics.

14. If we want to take seriously the question of how individuals and groups define their self-interest, we might turn to the “historical institutionalist” literature, which argues that institutional context shapes actors' goals. For historical institutionalists, preferences are affected not just by institutions themselves but by leadership and such factors as new ideas (such as Keynesianism). A good place to start is Structuring Politics: Historical Institutionalism in Comparative Analyses, edited by Sven Steinmo, Kathleen Thelen, and Frank Longstreth (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992). An important theoretical perspective is found in Jack Knight, Institutions and Social Conflict (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

15. Michael Johnston's essay in Diamond and Plattner provides some useful hints for Latin Americanists. Johnston argues that British and U.S. patterns of corruption were different. In Britain, corruption came from above, from government officials, for the purpose of keeping voting under control. In the United States, corruption stemmed from parties and other ethnic entrepreneurs trying to organize power bases. Reform in Britain was accomplished mostly by “new men” and some industrial interests seeking to challenge old elites. In the United States, reform was supported by those displaced by the new immigrants rather than by old elites responding to urban bosses.

16. See Harry Eckstein, “Case Study and Theory in Political Science,” in Handbook of Political Science, vol. 1, Political Science: Scope and Theory, edited by Fred Greenstein and Nelson Polsby (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1975), 85.

- 29

- Cited by