Article contents

Agricultural Policy and Politics: Theory and Practice

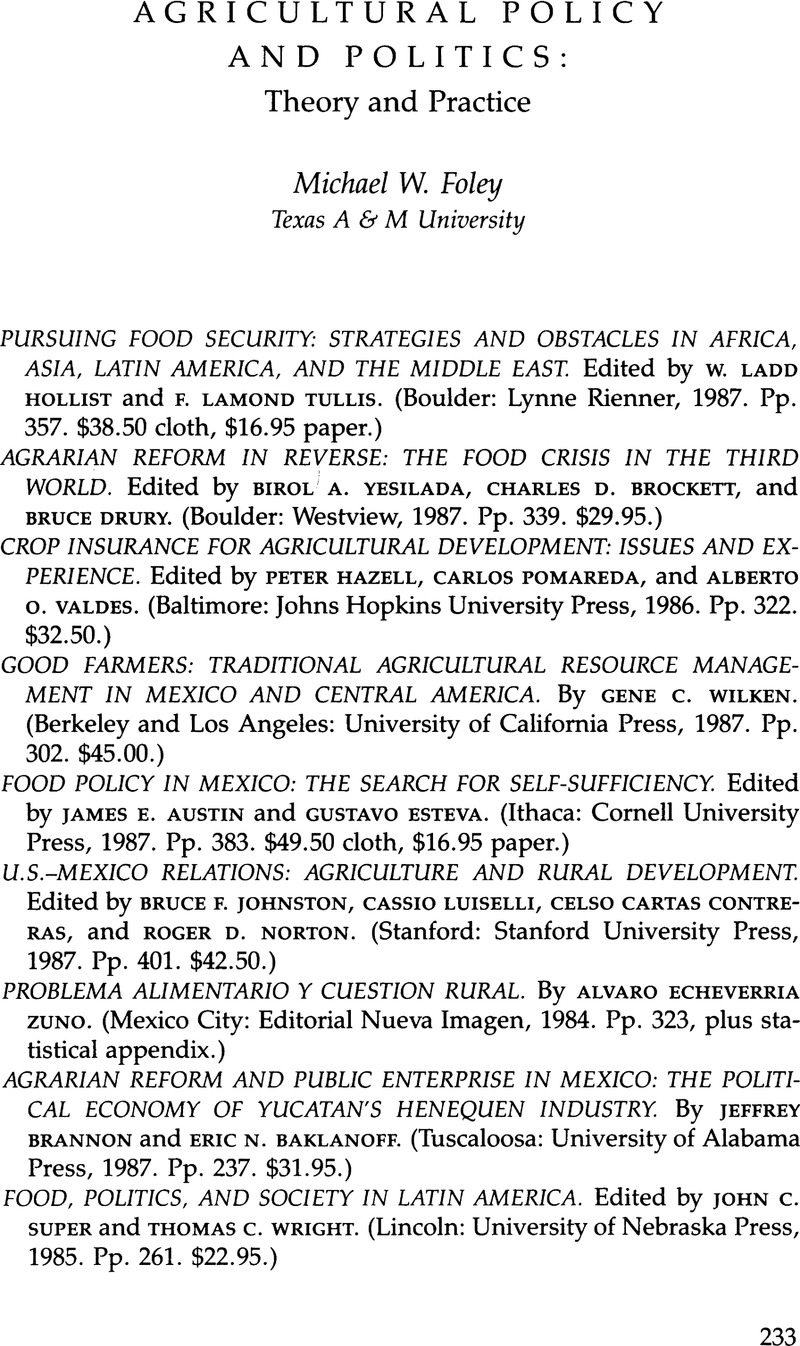

Review products

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 October 2022

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essays

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 1989 by the University of Texas Press

References

Notes

1. According to U.S. State Department analyst Dennis Avery, technological breakthroughs, particularly in genetic engineering, will mean an accelerating trend in this direction. See Avery, “Tomorrow's Environment for Agricultural Development,” paper presented at the Latin American Studies International Congress, New Orleans, 17–19 Mar. 1988. Even now, Avery points out, “Yield trends are not rising as rapidly in LDCs as in the developed countries—but they are generally rising as rapidly as effective consumer demand” (p. 3). The key term, however, is effective consumer demand. If commodity prices continue their decline in response to the trend pointed out by Avery, we can expect a continued decline in the buying power of those who depend on agricultural production for their livelihoods. In other words, we can expect continuing, perhaps increasing, world hunger.

2. The first position is best represented by Theodore Schultz and the “formalists” in the substantivist-formalist debates within economic anthropology. See Schultz, Transforming Traditional Agriculture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1964). The second position derives from the seminal work of A. V. Chayanov, The Theory of the Peasant Economy (Homewood, Ill.: Richard D. Irwin for the American Economics Association, 1966). This theory reappears as “substantivism” in economic anthropology in the wake of Karl Polanyi's massive synthesis, The Great Transformation (New York: Rinehart, 1944), and lies behind the so-called campesinista position in the Mexican debate. On this debate, see note 3.

3. See Ann Lucas, “El debate sobre los campesinos y el capitalismo en México,” Comercio Exterior 32, no. 4 (Apr. 1982):371-83; and Ernest Feder, “Campesinistas y descampesinistas: tres enfoques divergentes (no incompatibles) sobre la destrucción del campesinado,” Comercio Exterior 27, no. 12 (Dec. 1977):1439-46, and 28, no. 1 (Jan. 1978):42–51. Probably the most representative work on the descampesinista position is Roger Bartra's Estructura agraria y clases sociales en México (Mexico City: Era, 1975); for the campesinista position, see Arturo Warman, Ensayos sobre el campesinado en México (Mexico City: Nueva Imagen, 1980).

4. The assimilation of the “household economy” into the framework of neoclassical economics was already well begun with Michael Lipton's oft-quoted “Theory of the Optimizing Peasant,” Journal of Development Studies 4 (Apr. 1968). See also the important effort of the CEPAL team that used a modified notion of the household economy to construct a useful anatomy of Mexican agriculture on the basis of the 1970 census, Economía campesina y agricultura empresarial (Mexico City: Siglo Veintiuno, 1982).

5. Although both national production figures and levels of imports suggest that governmental programs continued to stimulate Mexican agriculture through 1985, thereafter the effects of the national economic crisis and the de la Madrid government's program of adjustment contributed to a wide-ranging agricultural crisis, heightened in 1988 by severe drought conditions. The story is brought up to date in a book that appeared too late to be included in this review essay, José Luis Calva's Crisis agrícola y alimentaria en México, 1982-1988 (Mexico City: Fontamara, 1988). Calva shows that under the politics of “adjustment,” government investment in agriculture fell by more than two-thirds. Guarantee prices for major crops also fell, as did available credit, while the prices of fertilizers, pesticides, and other inputs steadily rose. Interest rates, particularly high under the anti-inflationary Pacto de Solidaridad Económica of December 1987, put a squeeze on agriculture, with the hardest hit being the perennially credit-poor peasant farmer. In effect, argues Calva, “the government has transformed a financial crisis into a crisis of production” that threatens the capacity of Mexican agriculture and the Mexican economy to renew themselves (p. 173). All of this was done to avoid cutting the largest drain on public resources, that 52 percent of public expenditures consumed in payments on the debt. Although Calva is sanguine about the nation's potential for self-sufficiency, analysts within the government argue that the stagnation of Mexican agriculture in the 1980s is not attributable to the policies of one government but reflects long-term trends, especially the exhaustion of the “easy” phase of agricultural expansion and investment. For these analysts, the next steps, which include the organization of peasants for more efficient production, will be slow and difficult, whatever the macroeconomic environment.

6. But this may say more about the U.S. political experience than about the exigencies of political organizing in agriculture in general. See Lawrence Goodwyn's passionate account of the rise and fall of the populist movement among U.S. farmers, Democratic Promise: The Populist Moment in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1976).

7. But for a more optimistic view, along with an excellent survey of recent peasant mobilization in Mexico, see Jonathan Fox and Gustavo Gordillo, “Between State and Market: The Prospects for Autonomous Grassroots Development in Rural Mexico,” manuscript, 1988.

8. Robert H. Bates, Markets and States in Tropical Africa: The Political Basis of Agricultural Policies (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1981).

9. The term bimodal comes from Bruce Johnston and refers to agricultural systems consisting of large-scale, highly capitalized commercial enterprises, on the one side, and a welter of undercapitalized, largely subsistence peasant farms, on the other. In Johnston's view, such a structure lacks the stimulating effects on the larger economy of a more unimodal structure, effectively dampening income in the countryside and with it demand for the products of agriculture and also for agricultural inputs, machinery, and consumer goods. See Johnston's article in U.S.-Mexico Relations; also Bruce F. Johnston and Peter Kilby, Agriculture and Structural Transformation: Economic Strategies in Late-Developing Countries (New York: Oxford University Press, 1975).

10. This argument has been well worked out for the Mexican case by Nora Hamilton in The Limits of State Autonomy: Post-Revolutionary Mexico (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982); and by Steven E. Sanderson, Agrarian Populism and the Mexican State: The Struggle for Land in Sonora (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1981).

11. See Jeffrey Sachs's stimulating comparison of Latin American and East Asian countries in the light of the debt crisis for a discussion of the possible sources of policy success and failure among these cases. See Jeffrey D. Sachs, “External Debt and Macroeconomic Performance in Latin America and East Asia,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2 (1985):523–73.

12. Alain DeJanvry, The Agrarian Question and Reformation in Latin America (Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1981).

- 2

- Cited by