On October 29, 2009, Argentine president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner announced a new policy: a program that would pay poor parents a monthly allowance per child, starting in November.Footnote 1 The announcement surprised even the bureaucrats who would process the payments (Interview, Former Social Security Bureaucrat in Argentina 2020). Only a few ministers participated with the president in the program’s creation. The policy, called Asignación Universal por Hijo (AUH), was a strategy to increase her popularity after a defeat in midterm elections (Peronist politician involved in AUH 2020). Despite multiple difficulties in implementation, 3.3 million children received the cash in November (ANSES 2012). This was Argentina’s rapid-fire adoption of a conditional cash transfer policy.

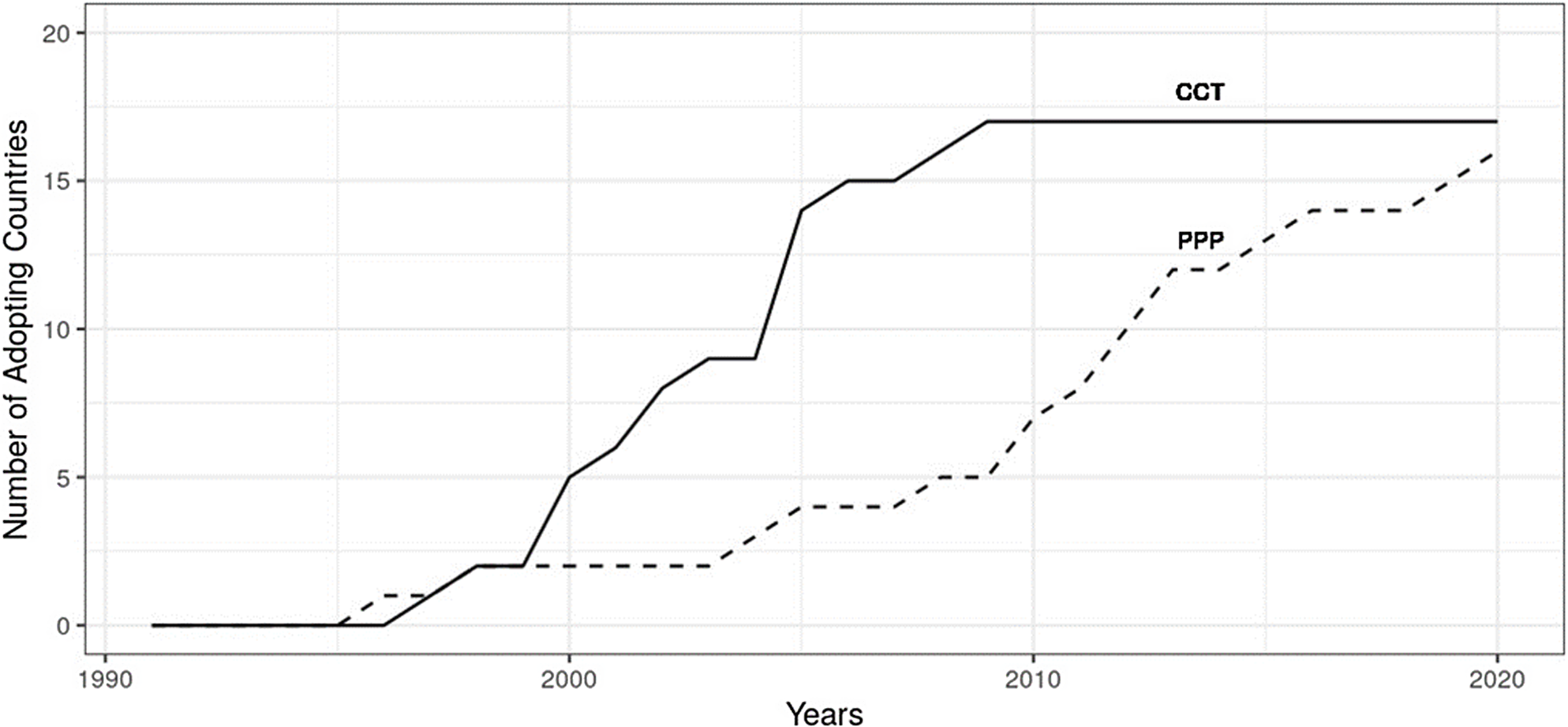

Conditional cash transfers (CCTs) kindled debates about policy diffusion, given how quickly the model spread (Sugiyama Reference Sugiyama2011; Morais de Sá e Silva Reference Morais de Sá e Silva2017; Borges Reference Borges2018; Osorio Gonnet Reference Osorio Gonnet2020). In Latin America, 17 countries adopted the model in 12 years, a rate of 1.4 adoptions per year (see online appendix A). This surge contrasts with most policies. At 0.7 adoptions per year, it took 20 years for 14 countries to adopt public-private partnerships (PPPs), a successful innovation that facilitates investments in infrastructure (see online appendix B).

Why were countries so eager to import CCTs but not PPPs? The explanation is that just like Cristina Kirchner in Argentina, presidents rushed the adoption of CCTs, expecting immediate gains in popularity. This article will show that CCTs attracted presidents’ attention because they expected the policy to boost their popular support very quickly—something all governments want. These rulers fast-tracked the policy’s enactment and implementation.Footnote 2 The aggregate result was a steeper curve of diffusion in the region, in comparison to PPPs’ careful adoptions leading to a standard diffusion wave.

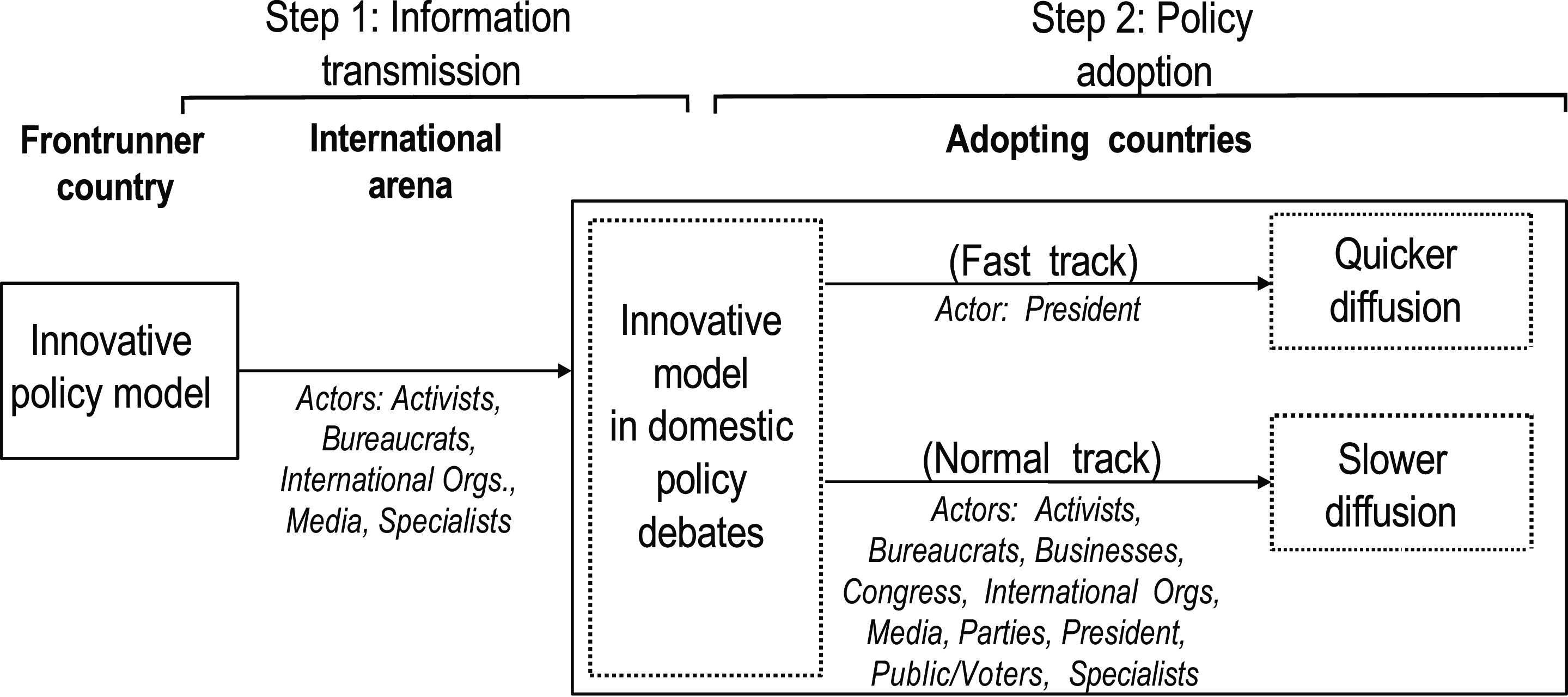

My argument defines diffusion as a two-step process: first, information about an innovation is transmitted across units; second, these units decide to adopt that innovation (Rogers Reference Rogers1995, 163; Weyland Reference Weyland2004, 14). Most of the literature about policy diffusion focuses on the first step and therefore emphasizes the role of international connections and influences, but that is not the crucial step that determines policies’ diffusion patterns.Footnote 3 Many actors may transmit information and promote a policy across countries. The crucial step that causes a policy to diffuse faster or not is the second one, where the model must be enacted and implemented in an institutionalized policymaking process. This article builds on previous research that highlights the importance of democratic competition for CCT adoptions (Brooks Reference Brooks2015; De La O Reference De La2015; Díaz-Cayeros et al. Reference Díaz-Cayeros, Estévez and Magaloni2016; Garay Reference Garay2016). This research focuses on how presidents’ expectations about the policies determined the different speed with which governments adopted CCTs and PPPs. In advancing and substantiating this argument, this study contributes to the literature on policy adoptions by placing an emphasis on the centrality of the executive branch.

Tracing the policymaking processes, the article shows that presidents fast-tracked CCTs because they expected to quickly boost their popularity. The research uses archival data from 17 Latin American countries that adopted at least one of the two policies analyzed. The findings show that the executive branch is the crucial gatekeeper of policy diffusion, as adoptions of both models in almost all countries only happened when presidents initiated them. But the role of presidents goes even further. They enacted conditional cash transfers unilaterally through decrees to speed up the process, while PPPs mostly followed congressional procedures. Similarly, presidents rushed the implementation of CCTs to the point that these programs suffered severe simplifications, while PPPs were implemented slowly and carefully. These different forms of adoption help explain why one policy diffused much faster than the other.

Case studies of Colombia and Argentina provide additional evidence for the causal link between presidents’ decision to fast-track CCTs—leading to the policy’s fast diffusion—and their expectation that the policy could boost their popularity. These cases are based on 8 months of fieldwork and 48 in-depth interviews with politicians, policymakers, and bureaucrats involved with these two policies (see online appendix C for cited interviews). Colombia and Argentina were selected for fieldwork because they provide two very different settings to test the argument.

Diffusion Waves and Diffusion Surges

Conditional cash transfers diffused in a “tidal wave” (Sugiyama Reference Sugiyama2011, 255) with impressive speed and range. Many authors emphasize how quickly countries jumped on the bandwagon (e.g., Valencia Lomelí Reference Valencia Lomelí2008, 476–77; Cecchini and Madariaga Reference Cecchini and Madariaga2011, 10–11). CCTs are a social policy that pays regular installments to families selected according to their level of poverty. These families must keep their children in school and take them to healthcare appointments to continue receiving the benefit. The model is a staple of social policy from Latin America. It was first created as a national policy in Mexico in 1997.Footnote 4 After 12 years, 17 countries in the region had adopted it (see figure 1).Footnote 5

Figure 1. Enactments of CCT and PPP in Latin America

By contrast, public-private partnerships (PPPs) did not diffuse nearly as quickly. The model created in the United Kingdom in 1992 (PPIAF 2009, 36) provides a legal framework that transfers the financial risks of infrastructure projects from the state to private investors, who may construct and manage them. These companies become responsible for negotiating loans in the market before they receive payments from the public budget. The policy ensures more efficient and secure investments for the state because all projects are evaluated not only by governments but also by the financial institutions involved. In Latin America, PPPs first appeared in Chile in 1996. After 24 years, they had been adopted by 16 countries.

Unfortunately, the diffusion literature lacks parameters to classify and compare diffusion curves in generalizable terms. Authors often present single-case studies, which they describe using terms like rapid spread (e.g., King and Sifaki Reference King, Sifaki, Nazneen and Hickey2019, 44) or wave (e.g., Elkins and Simmons Reference Elkins and Simmons2005). This study compares the diffusion speed of CCTs and PPPs, analyzing the number of countries that adopted the policies and the time it took for all these adoptions. This comparison raises the question, What explains such a striking difference between CCTs’ and PPPs’ diffusion curves? Or generally, Why do some policies diffuse faster and to more countries than others?

The diffusion literature has centered its attention on how information about a policy spreads. Key approaches followed Rogers’s initial definition of diffusion as the “process by which an innovation is communicated through certain channels over time among members of a social system” (Rogers Reference Rogers1995, 5). This conceptualization neglects the second step necessary for diffusion: the decision to adopt the innovation. Theories of rationality (Meseguer Reference Meseguer2004; Makse and Volden Reference Makse and Volden2011) and bounded rationality (Weyland Reference Weyland2006) predict that success and availability induce widespread adoption through learning or imitation. These characteristics, however, tell us little about the political returns governments expect from a policy. Similarly, theories of imposition (Eichengreen and Rühl Reference Eichengreen and Rühl2001; Hanson Reference Hanson2003) emphasize the role of great powers and international organizations, framing governments as weak reactive actors. Arguments centered on values and ideas (Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Ramírez, Rubinson and Boli-Bennett1977; Finnemore and Sikkink Reference Finnemore and Sikkink1998) see diffusion as a result of global norms that policymakers feel pressured into following if they want to be considered respected members of the international community.Footnote 6

In sum, theoretical approaches have successfully explained one aspect necessary for policy diffusion: the dynamics through which information about models is transmitted. Yet out of all ideas transmitted into a country, only a few find their way into enactment and implementation—and the executive plays a key role in selecting which ones. Patterns of diffusion depend not only on how many countries are exposed to a new policy but even more on how many governments adopt it. The second step is the most difficult one. This article complements approaches centered on transnational dynamics by focusing on the domestic policymaking process of diffusing models.

Some studies get closer to domestic adoption. Jordana et al. (Reference Jordana, Levi-Faur and i Marín2011, 1347), for example, discuss adoption processes as integral to the dynamics of diffusion. Approaches centered on domestic characteristics, like the executive’s ideology (Gilardi Reference Gilardi2010), the size of the state and the economy (Francesco Reference Francesco2012, 1287), or even the level of repression (Meseguer Reference Meseguer2004) are useful to explain why some countries are early or late adopters. Usually included in statistical models, these variables cannot explain the difference between the diffusion patterns of policies across the same countries. With a focus on pressure from the general public, Linos (Reference Linos2013) frames governments as passive actors in the face of voters. Weyland (Reference Weyland2006) highlights bureaucrats’ role in importing ideas from abroad. This study’s main contribution lies in a focus on the executive branch and its central role in policymaking, which allows presidents to determine when and how quickly a model is adopted (See Osorio Gonnet Reference Osorio Gonnet2015 for a case study of CCTs in Chile that also highlights presidents’ role in the adoption of models from abroad). In the aggregate of multiple countries, presidents’ interests are crucial for a model’s diffusion.

In the case of CCTs, studies analyzing the policy’s adoptions through the lens of diffusion theories follow the general patterns of the literature of policy diffusion. Multiple studies argue that a country’s exposure to successful CCT models in the region influences its decision to adopt the model (Brooks Reference Brooks2015; Papadopoulos and Velázquez Leyer Reference Papadopoulos and Leyer2016, 440; Osorio Gonnet Reference Osorio Gonnet2020, 109; Sugiyama Reference Sugiyama2011). Other explanations include promotion by international organizations (Sugiyama Reference Sugiyama2011; Papadopoulos and Velázquez Leyer Reference Papadopoulos and Leyer2016, 440) and epistemic communities (Osorio Gonnet Reference Osorio Gonnet2019), and the emergence of global norms (Sugiyama Reference Sugiyama2011). These factors refer to how the policy idea travels and is received across borders—but they do not explain why governments adopt the idea much faster than other ideas traveling in similar ways. These diffusion analyses of CCTs neglect the political aspect of policymaking, looking mainly at countries’ characteristics, such as income and inequality (Osorio Gonnet Reference Osorio Gonnet2020), socioeconomic conditions (Sugiyama Reference Sugiyama2011), and state capacity (Osorio Gonnet Reference Osorio Gonnet2019; Sugiyama Reference Sugiyama2011)—and yielding mixed results. The exception is the finding that democratic countries are more prone to adopting the policy (Brooks Reference Brooks2015; Papadopoulos and Velázquez Leyer Reference Papadopoulos and Leyer2016).

Beyond the diffusion literature, studies focused on the domestic processes that created conditional cash transfers programs also identify the importance of democratic pressures in the policy’s adoption. Electoral competition was a crucial factor that mobilized governments to implement CCTs (Díaz-Cayeros et al. Reference Díaz-Cayeros, Estévez and Magaloni2016), either when they had to curb social mobilization and defeat electoral challengers (Garay Reference Garay2016) or when they faced economic crises (De La O Reference De La2015). This article’s research bridges the gap between findings about the importance of democratic pressure for CCTs and a more general theorization about diffusion by comparing that policy with public-private partnerships.

By applying an institutional focus to domestic policymaking (Skocpol Reference Skocpol1992; Spiller et al. Reference Spiller, Stein, Tommasi, Stein and Tommasi2008), I argue that presidents seeking popularity to stay in power in democratic countries affect policies’ diffusion. Chief executives’ centrality in policymaking is magnified in the adoption of diffusing models because they can quickly push a blueprint from abroad into enactment and implementation. Presidents can apply extraordinary powers to accelerate the adoption of CCTs, hoping to increase their popularity. Policies that could not boost presidents’ popular support, like PPPs, do not enter the same presidential fast-track of adoption. In the aggregate result, CCTs’ fast-tracked adoptions across the region resulted in a faster diffusion compared with PPPs, which followed normal policymaking processes.

Presidents at the Center

This article concentrates on the process of policy adoption as a key part of diffusion. It extends Rogers’s initial definition of diffusion (Reference Rogers1995, 5) to include adoption as a necessary second step (Weyland Reference Weyland2004, 14). Diffusion, therefore, is a process that happens to an innovation created by one unit of a social system, when information about that innovation is spread to other units (first step) and these units adopt that innovation (second step). If two new policy ideas spread simultaneously, the policies might diffuse very differently if most countries adopt one faster than the other. This conceptualization recovers a neglected part of Rogers’s book, the “innovation-decision process” (Reference Rogers1995, 161).Footnote 7

A focus on political decisionmaking is particularly important for this argument on adoptions because policymaking follows institutionally defined processes of enactment and implementation.Footnote 8 This institutional structure makes it easier to identify the key actor involved in policy adoptions: the president. Studies of diffusion have emphasized the role of different actors who transmit and promote policy ideas, like specialists (Haas Reference Haas1992), elites (Smith Reference Smith2013), and parties (Böhmelt et al. Reference Böhmelt, Ezrow, Lehrer and Ward2016). But the institutional adoption process privileges the executive branch (Scartascini Reference Scartascini, Stein and Tommasi2008; Morgenstern et al. Reference Morgenstern, Polga-Hecimovich and Shair-Rosenfield2013), especially in a region where presidential systems abound, like Latin America (Figueiredo and Limongi Reference Figueiredo and Limongi2000). For a policy to diffuse quickly it must attract presidents’ attention.

Public Support, Presidents’ Attention, and Policy Fast-tracking

Presidents’ fundamental goal is to remain in power, which depends on public approval. That support is crucial not only in elections but also as protection against impeachment (Hochstetler Reference Hochstetler2006; Pérez-Liñán Reference Pérez-Liñán2007). Moreover, popular presidents have an easier relationship with Congress (Altman Reference Altman2000; Calvo Reference Calvo2007). Neustadt’s insight (Reference Neustadt1990) that presidents’ persuasive power depends on their prestige with the public remains true. Therefore, policies that generate immediate support grab presidents’ attention more than others. Presidents may be interested in policies that advance their ideological positions, governmental plans, economic objectives, and constituents’ interests. Popular support, however, stands out before presidents’ eyes—because without support they cannot advance their agenda. Policies expected to boost popularity move to the top of presidents’ priority list, especially in competitive democracies and in contexts of crisis—factors highlighted in the literature about CCTs’ adoptions (Brooks Reference Brooks2015; De La O Reference De La2015; Díaz-Cayeros et al. Reference Díaz-Cayeros, Estévez and Magaloni2016; Garay Reference Garay2016).

Policymaking follows institutional processes that make it difficult to change the status quo, but policy models coming neatly packaged from abroad can avoid that resistance more easily. New policy ideas usually emerge in specialized groups and must undergo long debates until they reach political consideration. Only ideas that survive these debates can enter macropolitics (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Jones, Mortensen, Weible and Sabatier2018). In the case of diffusion, policies are coherent and readily available models coming from abroad (Weyland Reference Weyland2004, 8). These innovations have already survived political debates in other countries, and they can serve as blueprints for quick adoption. Still, only some models are adopted quickly.

Presidents have the means to fast-track policy adoptions. They have access to specialized debates among think tanks, researchers, interest groups, and bureaucrats, as well as institutional powers to turn ideas into policies. Decrees allow for unilateral enactment. After enactment, presidents control the bureaucracy to rush implementation. Even if presidents do not have the same powers across Latin America, they always have significant policymaking privileges (Morgenstern et al. Reference Morgenstern, Polga-Hecimovich and Shair-Rosenfield2013). Variation in these powers may explain why some countries are early or late adopters, but it does not affect the comparison between two policies’ diffusion patterns. Figure 2 shows the dynamics of policy diffusion emphasizing the fast-track of policymaking.

Figure 2. Dynamics of Policy Diffusion

However, fast-tracking a policy can be costly for democratic rulers. First, the overuse of unilateral powers evokes concerns about accountability (Mainwaring and Shugart Reference Mainwaring and Shugart1997, 465; Negretto Reference Negretto2004, 556) and complaints from Congress (O’Donnell Reference O’Donnell1994, 66). Second, it can generate negative reactions from the public (Amorim Neto Reference Amorim Neto2006, 420), so a policy enacted unilaterally must outweigh the popularity costs of decrees (Kang Reference Kang2020). Presidents apply those unilateral powers to models that can provide immediate popularity boosts. These policies must benefit a large part of the population immediately, and they must be directly attributable to the president. When a model with these characteristics arrives in domestic debates, presidents can enact it unilaterally and rush its implementation. The result is a fast adoption in each country and a steeper diffusion curve.

The process is usually slower for a model that does not benefit many people in the short term, or one that presidents could not easily claim as their own. The appeal from this type of policy comes mainly from the success observed in other countries, but that success does not address a universal concern of rulers, like popularity. Fewer governments will be interested in these models, and even the interested ones will not be rushed to adopt them, so fast-tracking is not necessary. Normal policymaking is enough. In the regional aggregate, diffusion takes longer to unfold.

Hypotheses and Expectations

My argument can be framed around two central hypotheses:

H1. Most presidents fast-track policy models from abroad expected to boost their popular support, and let other policies follow normal policymaking processes.

H2. Presidents decide to fast-track those policies because they want to boost their popular support quickly.

H1 makes an easily observable claim, while H2 focuses on a latent aspect of the process: presidents’ motivations. This research applied a process-tracing analysis (Collier Reference Collier2011; Bennett Reference Bennett, Brady and Collier2010) to compare the diffusion of CCTs and PPPs. For H1, it used data from 17 Latin American countries to identify the policymaking processes followed by governments to adopt CCTs and PPPs. The large number of countries required a structured approach based on data directly extracted from official documents. That structure took the form of three hoop tests that encompass the central elements of the hypothesis:

-

A. Presidents are preponderant in the adoption of policy models. This test provides evidence of the unrivaled power of presidents in adopting policy ideas from abroad.

-

B. Presidents enact popularity-boosting policies unilaterally. This test refers to the argument’s core about fast-tracking CCTs but not PPPs, looking at the policy’s enactment into law.

-

C. Presidents rush implementation of popularity-boosting policies. This test also addresses the argument’s points about fast-tracking CCTs but not PPPs, now focused on the implementation.

Individually, tests A, B, and C are necessary to confirm the first hypothesis. Combined, they cover the key stages in the policymaking process and thus add up to a sufficient empirical test.

H2 refers to the unobservable perceptions and preferences of presidents. The evidence available to test that hypothesis comes from fieldwork in two countries, Argentina and Colombia. The main source of data are in-depth interviews conducted with politicians, policymakers, bureaucrats, and other people directly involved in the adoption of CCTs and PPPs in those countries. Insights from those influential individuals make it clear that presidents and their inner circles decided to fast-track CCTs because they saw it as a popularity-boosting policy, something that PPPs were not.

Empirical Strategy

Conditional cash transfers and public-private partnerships established new policy paradigms in their areas. CCTs provide direct cash installments to families below a poverty threshold. To receive the transfers families’ children must fulfill conditions like attendance in school and healthcare appointments. The policy was quickly recognized as effective against extreme poverty (Skoufias et al. Reference Skoufias, Parker, Behrman and Pessino2001; Rawlings Reference Rawlings2005). The World Bank, UNICEF, and other organizations championed CCTs across the Global South (Milazzo and Grosh Reference Milazzo and Grosh2008; García and Moore Reference García and Moore2012).

Public-private partnerships move the financial risks of infrastructure projects from the state to private companies (OECD 2008, 17), allowing for faster and more rational investments. Private partners must generate upfront funds, getting credit in the market. Their revenue comes from payments by the state or by users after parts of the construction are ready. With PPPs, governments can start building infrastructure without incurring immediate expenditures. Projects under this model are more efficiently designed because they must be approved by lenders in the financial market. The policy became part of the New Public Management paradigm (Schedler and Proeller Reference Schedler, Proeller, McLaughlin, Osborne and Ferlie2002, 164–165; Yescombe and Farquharson Reference Yescombe and Farquharson2018, 451–53), and it was promoted internationally by specialists, bureaucrats, businesses, and organizations. Since 1999, the World Bank has an office dedicated to helping governments adopt PPPs, called Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility (PPIAF).

CCTs and PPPs match the main criteria theorized in the diffusion literature about the first step of diffusion. Both are clear, innovative solutions that efficiently solve the problems they are intended to tackle. From the start, they were both perceived as successful in this regard. The two models also counted on the support of several transnational actors, making information about the policies easily available to governments. Moreover, powerful international organizations promoted both models, as expected by theories of imposition. They also match the normative expectations and cultural rules associated with their respective areas: poverty reduction with a focus of human capital in the case of CCTs; economic development associated with public budget control for PPPs. Therefore, the different diffusion patterns between CCTs and PPPs must be explained by their differences regarding the second step of diffusion.

Other aspects of the policies may differ, but factors previously theorized as causes of diffusion are similar for both. The most obvious difference is that CCTs fight poverty while PPPs fund infrastructure. The choice of cases from different areas ensures independence between them. Comparing policies from the same issue area and the same period would affect the necessary assumption that there is no spillover across cases. If we were to compare CCTs with another social policy, the second one could have failed to diffuse because governments focused their attention on CCTs.

Some rival explanations for the different speed of diffusion must be considered. The first is the cost of implementation. CCTs are an inexpensive policy (Saad-Filho Reference Saad-Filho2015, 1237; Teichman Reference Teichman2008, 448), but PPPs are even cheaper. First, the policy is a legal framework with very low initial costs. Second, its implementation in construction projects transfers immediate expenses to private partners, pushing budgetary concerns toward the future (Yescombe and Farquharson Reference Yescombe and Farquharson2018, 453). A president willing to develop infrastructure could use PPPs without upfront costs. Cost-effectiveness, therefore, cannot explain the different waves of diffusion.

The second rival explanation concerns the complexity of the model. A complex policy that requires a long process of implementation is likely to diffuse slowly. PPPs and CCTs are simple ideas, but both models are difficult to implement properly as governmental programs. The complexity of both policies is evident in the similar number of governmental entities involved in each of them. In Argentina, the PPP law (Ley 27328/2016) refers to 14 entities, including local governments and the Ministry of the Environment, while the decree that created CCTs (Decreto 1602/2009) cites 13 of them. In Colombia, the situation is inverted. While the PPP law (Ley 1508/2012) cites 15 entities, the document that established CCTs (CONPES 3081/2000) cites 17 (see appendix D). On paper, therefore, the two policies are similarly complex.

In practice, however, the implementation of CCTs presents two big challenges. The first is the need to identify, reach, and pay thousands or millions of beneficiaries across the territory (Paes-Sousa et al. Reference Paes-Sousa, Regalia and Stampini2013, 82), based on a general measurement of poverty. In contrast to previous social programs in Latin America that focused on workers with a connection to the formal labor market, CCTs intend to include informal workers’ families (Mazzola Reference Mazzola2012, 48; Paes-Sousa et al. Reference Paes-Sousa, Regalia and Stampini2013, 2; Garay Reference Garay2016) and rural communities (Levy Reference Levy2006, 85). While formal workers’ income and employment situation are easily accessible to the government, identifying poor households among informal workers living in remote regions requires large amounts of data about families that governmental policies have ignored in the past (Levy Reference Levy2006, 91–92). This population is much harder to reach and identify. They might not have access to banks and may even lack basic identity documents (Hunter Reference Hunter2019). An army of social workers spread throughout the country must reach those families to collect their information, enroll those included in the program, and provide the means for them to receive the benefits (Cecchinni and Madariaga Reference Cecchini and Madariaga2011, 14–42).

The second challenge is controlling conditionalities, which previous social policies did not need. Once a family enters a CCT program, teachers and healthcare providers must report its children’s attendance at school and health clinic visits to the program’s central administration. Most presidents implemented a loose control of conditionalities to accelerate the program’s implementation. However, even those programs needed integration with healthcare and education bureaucracies to ensure that those services were available and to take attendance. The result is a complex vertical and horizontal coordination among multiple ministries and agencies, involving bureaucrats spread over the territory, to establish long-term contact with every beneficiary and their children.

Implementing PPPs does not require the same territorial outreach or permanent coordination with street-level bureaucrats. The policy’s legal framework needs specialized bureaucratic and legal teams to create and analyze projects, select contractors, and apply the regulations. The projects must include a long set of specifications about potential issues in the project, which involves coordination with multiple ministries and agencies. However, nearly all the work remains centralized in bureaucrats’ offices in the capital. The actual construction of infrastructure is conducted and managed by private contractors, reducing the burden on the government. Naturally, this also reduces presidents’ control over the construction phase of PPP’s implementation. For this reason, I consider PPPs fully implemented when the state presents at least one project in a public offer for investors, irrespective of whether or when partnerships were signed or construction started. This coding ensures comparability with CCTs by focusing only on what the executive can directly control. Presidents cannot dictate the time it takes for private companies to sign contracts and build projects, but they can push bureaucrats to develop and present the projects to investors faster. Even with that minimal definition, PPPs’ implementation takes much longer than CCTs’.

A third rival explanation invokes ideology. The individual ideology of each government does not change the diffusion pattern, and it cannot explain the difference between two policies’ waves. But Latin America’s Pink Tide of leftist governments in the early 2000s, some could say, might explain why an antipoverty policy diffused so fast while a neoliberal one did not. The truth, however, is that governments from both left and right adopted both policies. Sugiyama (Reference Sugiyama2011) and Osorio Gonnet (Reference Osorio Gonnet2020, 111–12) point out that ideology did not drive CCTs’ diffusion surge, while Borges reveals that the left initially rejected them. The policy “carried the stench of neoliberalism” (Reference Borges2018, 149), due to its focus on human capital development and its association with institutions like the World Bank.Footnote 9 In the case of PPPs, there is also a spread of adoptions across the ideological spectrum. Contrary to the expectations of an argument centered on ideology, leftist presidents enacted the model in nine countries, compared to only five enacted by right–wing governments.Footnote 10 Moreover, contrary to what happened with CCTs, leftist leaders were the first ones to jump on the PPP bandwagon: Costa Rica’s José María Figueres Olsen in 1998, Brazil’s Lula da Silva in 2004, and Peru’s Alan García in 2008. If anything, ideology would have hindered the diffusion of CCTs during Latin America’s pink tide, not PPPs. My findings show that CCTs’ promise of a popularity boost overcame ideological concerns.

Table 1 summarizes the similarities that allow for a comparison between the two policies. Both share the factors that should facilitate their fast diffusion. The puzzle is clear: Why did CCTs diffuse much faster than PPPs? My explanation lies in presidents’ expectations of the policies’ political effects. CCTs attracted presidents’ attention because they expected a popularity boost from them. Political leaders quickly identified that delivering cash to poor families could generate quick political support, and that the program would be easily attributable to the presidency. Their intuition found echoes in academia (Hunter and Power Reference Hunter and Power2007; Zucco Reference Zucco2008; Díaz–Cayeros et al. Reference Díaz-Cayeros, Estévez and Magaloni2016).Footnote 11 PPPs did not generate the same expectation. Even if building infrastructure is a pressing issue for many countries, and presidents campaign on the topic (e.g., PT 2002; Colom Reference Colom2007; Santos Reference Santos2010), construction takes years, and these projects are hardly attributable to a single president.

Table 1. Comparability of CCTs and PPPs (extant arguments)

Results

Data about the adoption of CCTs and PPPs in Latin American countries allow for an assessment of the first hypothesis. This analysis uses official documents and secondary sources from the policymaking process in 17 countries in the region that adopted at least one of the policies after the innovators (Mexico for CCT and Chile for PPP). Table 2 shows that presidents initiated almost all adoptions and that they applied unilateral enactment powers almost exclusively on CCTs. Numbers in test C show an important difference in how the models were implemented (see appendixes A and B).

Table 2. Tests for Hypothesis 1

Test A: Presidents Are the Key Actors in the Adoption of Policy Models

The analysis of CCTs and PPPs confirms that presidents largely determine which ideas from abroad get adopted and when. All enactments of CCTs were initiated by the executive branch, and only two enactments of PPPs did not follow that pattern. Despite the two outliers (Paraguay and the Dominican Republic), the numbers confirm that an argument centered on the second step of diffusion must look primarily at the expectations and interests of presidents. Ultimately, the existence of a blueprint successfully implemented abroad allowed presidents to bring these models directly into macropolitics. But they did not follow the same policymaking path for both policies.

Test B: Presidents Push Enactment of CCTs Unilaterally

This is the most striking result of this analysis: all presidents but one used unilateral powers to enact CCTs, while only two did the same with PPPs (see appendixes A and B). Most unilateral enactments used decrees, but some were arranged through agreements with international organizations. All of them allowed the president to immediately change the status quo. Congress had a say on the policy only later, when approving decrees or voting the budget. After the president’s announcement of the CCT program, members of Congress would face political costs if they decided to shut down such a popular policy. A Chilean bureaucrat stated that congressional lawmaking was inconsequential after unilateral enactment: “If the law is approved, that would be great, but if it is not, we are already doing it and we can continue to act with the tools we have” (quoted in Ruz and Palma Reference Ruz and Palma2005, 37).

Conversely, the enactment of PPPs followed normal policymaking processes in almost all cases, which led to an average time from initiation of the bill to enactment of more than nine months (275 days). In Mexico and Costa Rica the process took an impressive 27 months. Peru and Argentina are the notable exceptions. Their unilateral enactments of the model show that presidents could adopt the policy without Congress.

In 2008, Peruvian president Alan García signed a decree establishing the law of PPPs (Decreto Legislativo 1012/2008) as part of a strategy to attract investments. Despite the singlehanded decision, a representative of the International Monetary Fund praised the policy and said that “businesspeople welcomed the measure” (Andina 2009). Interviewees in Colombia and Argentina saw Peru’s legislation as an example for their countries.

We looked at the laws that worked in the UK, Chile, and Peru, and then created our own. (Colombia, PPPs Bureaucrat #3 2019)

In Latin America, we looked more at the cases of Peru and Colombia. (Argentina, PPPs Office Bureaucrat #1 2020)

Peru’s enactment would be enough to show that presidents could successfully enact PPPs unilaterally if they wanted to. However, Argentina also enacted PPPs unilaterally: in 2005, President Néstor Kirchner signed a decree establishing the policy. Despite imitating Brazil’s law, that decree was not implemented, due to Argentina’s recent history of default. It ended up substituted by a new law approved by Congress in 2016.Footnote 12

Test C: Presidents Rush the Implementation of CCTs

After using a decree to circumvent Congress and quickly enact CCTs, presidents wanted an equally fast implementation. In most cases, payments started within a couple of months, and in some countries, like Argentina, they immediately reached millions of beneficiaries. Since presidents’ pressure to fast-track the model was driven mostly by the hope of receiving a big popularity boost from the policy, CCTs’ fast implementation focused on delivering cash transfers immediately while neglecting other aspects of the policy, such as the monitoring and enforcement of conditionalities. In line with my argument, the rush to distribute the benefits resulted in simplifying and compromising CCT programs. This reduction in the policy’s quality resulted directly from presidents’ urgent political interests.

Studies have identified several problems in the implementation of CCTs across the region. Most common were errors in the selection of beneficiaries and a lack of adequate control of their compliance with conditionalities (e.g., Cetrángolo and Curcio Reference Cetrángolo and Curcio2017; Osorio Gonnett Reference Osorio Gonnet2020, 189; Britto Reference Britto2008; Gaia Reference Gaia2010, 208; Moore Reference Moore, Adato and Hoddinott2010, 108; Rivarola Reference Rivarola, Cohen and Franco2006, 381; Schady et al. Reference Schady, Caridad Araújo, Peña and López-Calva2008, 69). In Peru, for example, the CCT program, first created in 2005, suffered from targeting errors and failed to control conditionalities (Dirección Nacional de Presupuesto Público 2008, 3–7). Even in Brazil, considered a flagship of the model, an evaluation from 2004 indicates that only 19 percent of schools submitted information about children’s attendance; “consequently, the imposition of penalties for noncompliance was even more rare” (de Janvry et al. Reference De Janvry, Finan, Sadoulet, Nelson, Lindert, Brière and Lanjouw2005, 23). These problems diminished CCTs’ effectiveness in reducing poverty and creating human capital. However, they did not affect the popularity boost that presidents expected from the simple payment of benefits. In fact, a problem like maintaining the benefit to families that do not fulfill all conditions may increase the number of beneficiaries and the expected gains in support.

Compared to CCTs, the implementation of PPPs was much slower across the region.Footnote 13 Even under the simple definition of implementation that considers the model implemented when governments present projects for potential private investors, most countries took more than one year to present the first project. Many took several years, and some have yet to use the law. As successful and publicized across borders as they were, PPPs did not promise a big popularity boost, and therefore were not highly attractive to presidents. The result was a series of careful implementations that ensured the involvement and agreement of multiple agencies and institutions without politically driven simplifications that could compromise the model, as in the case of CCTs.

Country Cases

The foregoing analysis confirms the first hypothesis: as the main actors in policymaking, presidents enacted CCTs unilaterally and rushed their implementation while allowing PPPs to follow slower processes. This difference helps explain the models’ contrasting diffusion patterns. It is now necessary to understand why presidents acted differently regarding these policies. The second hypothesis states that their motivation was the immediate popularity boost expected from CCTs. While it is impossible to directly observe presidents’ reasoning, an indirect picture can be gained by interviewing people surrounding the president or involved in the policymaking process. Months of fieldwork in Colombia and Argentina collected data from 48 interviews with politicians, policymakers, and bureaucrats who had a role in these policies to uncover why presidents decided to fast-track CCTs but not PPPs.

The selection of Colombia and Argentina follows the methodological goal of showing that my argument applies to very different domestic contexts, bolstering confidence in its generalizability. The comparison between CCTs and PPPs across the region isolated the causal factor (presidents’ expectations about the policy). Now, the in-depth study of these two countries shows that cause at work in political environments that differ in geographical position, ideology, foreign alignment, engagement with international organizations, and executive strength (Kestler et al. Reference Kestler, Lucca and Krause2016). Moreover, Colombia adopted CCTs early, serving as a typical case, while Argentina is the least likely case for fast-tracking CCTs. It was the last country in Latin America to fully adopt the model because its large parties depend on clientelism (Oliveros Reference Oliveros2016) and regional leaders (Kikuchi Reference Kikuchi2018), two strategies negatively affected by CCTs (Sugiyama and Hunter Reference Sugiyama and Hunter2013).

CCTs in Colombia

The adoption of CCTs in Colombia follows my expectations. The government created the program Familias en Acción in 2000 during the country’s deepest economic crisis in 60 years (Echeverry and Zuluaga Reference Echeverry, Zuluaga, Argáez and Pizano2014, 280). Its enactment arose from unilateral decisions made by the president, Andrés Pastrana, who rushed implementation despite requirements for careful testing by international organizations. Interviews with members of the administration confirmed that the key motivation to adopt the model was a fear of popular discontent.

The crisis hit Colombia only three years after Mexico implemented the first CCT program. Austerity measures to save the economy affected the government’s approval ratings, and the innovation came as a solution to appease the masses.

We had to get help from the IMF, but their program was very unpopular, or at least we thought it would be. It was necessary to do something that could lend it a more friendly face, … because it had unpopular elements of austerity. This [the CCT model] was seen as an antidote against that. (Member of Pastrana’s and Santos’s cabinets #2 2019)

Pastrana’s popularity had fallen more than 10 percentage points in his first year (Carlin et al. Reference Carlin, Jonathan Hartlyn, Love, Martínez-Gallardo and Singer2019), due to the crisis, failed negotiations with guerrillas, and the implementation of Plan Colombia. Bureaucrats linked to the president’s cabinet proposed a CCT program similar to Mexico’s model.

This was a program that the president loved! He deeply appreciated it when we said he could spend funds on this program.….This is a politically wonderful program. So amid all political costs of Plan Colombia, this was very well received by him. (Member of Pastrana’s and Santos’s cabinets #1 2019)

Pastrana and his cabinet enacted CCTs unilaterally right away, on March 15, 2000, using a legal mechanism called CONPES. Issued by a council within the executive branch, these documents determine administrative decisions without participation from Congress. The use of CONPES served to avoid debates in the parliament, not only to hasten implementation but also because every congress member would ask for implementation first in their own town (Member of Pastrana’s and Santos’s cabinets #3 2019), so they could reap political benefits at expense of the president’s claim over the program.

After enactment, the president also rushed the program’s implementation. While bureaucrats worked hard to identify beneficiaries, the president complained that they were the only ones who could not find poor people in Colombia (Member of Pastrana’s and Santos’s cabinets #1 2019). International organizations required pilot tests before full implementation (Member of Pastrana’s and Santos’s cabinets #1 2019; Social Policy Bureaucrat in Colombia 2019), but the government put Familias en Acción in motion before these pilot results (Familias en Acción Bureaucrat #2 2019). It also made immediate political use of events with up to 50 thousand people, where the president met beneficiaries.

We got used to working politically. Even before the first year we already had 150 thousand families [enrolled] because Pastrana realized it [the program’s political benefit]. (Familias en Acción Bureaucrat #2 2019)

The program remained under the president’s direct control, which allowed for implementation in record time (Cárdenas Reference Cárdenas, Caballero and Pizano2014, 187–89; Combariza Reference Combariza2010, 250). In 2001, the government had already paid benefits to more than one million people.

CCTs in Argentina

Argentina created its CCT program, Asignación Universal por Hijo (AUH), in 2009. The country already had other cash transfers that were not the typical Mexican CCT. The first program came as a solution to the 2001 economic crisis, but it targeted unemployed formal workers rather than extreme poverty (Kliksberg and Novacovsky Reference Kliksberg and Novacovsky2015, 30; Perelmiter Reference Perelmiter2016, 51). A second, smaller program, called Plan Familias, kept the same focus in 2005 (Marchionni and Conconi Reference Marchionni and Conconi2008, 21; Perelmiter Reference Perelmiter2017, 271). These two programs remained associated with discretionary decisions and clientelist strategies (Perelmiter Reference Perelmiter2017).Footnote 14 The Peronist government ignored six initiatives in Congress to adopt the Mexican model of CCTs (Díaz Langou Reference Díaz Langou2012, 13), as its members strongly rejected centralized strategies for social policies (Perelmiter Reference Perelmiter2016, 102).

Alicia [Kirchner, Minister of Social Development] was against it because she came from a tradition of direct policies, in which one can see the beneficiary. (Member of C. F. Kirchner’s Cabinet 2020)

Still, the promise of popularity gains from full-fledged CCTs was too attractive, and that same Peronist government rushed its adoption in a moment of weakness. President Cristina Kirchner faced a political crisis that started in a conflict with agribusiness in 2008 (Pucciarelli Reference Pucciarelli2017) and ended with a defeat in the 2009 midterm elections (Gené Reference Gené2017, 392–93). The electoral result came as an alert.

Even though we had won among the poor sectors [of the population], this time we won by just a bit.… We were not reaching that group very well anymore. (Member of C. F. Kirchner’s Cabinet 2020)

The president’s approval ratings had plummeted from 50 percent at the beginning of 2008 to 30 percent in mid-2009 (Carlin et al. Reference Carlin, Jonathan Hartlyn, Love, Martínez-Gallardo and Singer2019). The minister of the economy, Amado Boudou, suggested the CCT model as an easy and readily available solution.

This happened after the 2009 elections, in which we were defeated. And the year before we had the conflict with rural producers. The idea was that you move forward from political crises, and there it [the CCT model] came as a response. (Peronist politician involved in AUH 2020)

Cristina Kirchner announced the program four months after the elections. The policy was kept a secret until the decree was issued, and its unilateral enactment avoided delays and ensured attribution to the president.

We were afraid that it [the CCT policy] would not pass in Congress, or that we could be surpassed by the left with something even more progressive. That is why we did it by decree. (Peronist politician involved in AUH 2020)

The idea that prevailed was to show it [the policy] as a direct decision of Cristina [Kirchner]. (Member of C. F. Kirchner’s Cabinet 2020)

The announcement in late October stated that the transfers would start the following month, surprising the team responsible for implementation.

She [the president] said that starting in November we would pay the stipend to everyone with [income of] less than two minimum wages, and I almost dropped dead. We had two million children without any records about their parents, and I would have to find out their income in a matter of days. (Former Social Security Bureaucrat in Argentina 2020)

There was also an unknown number of unregistered children. A large operation was put in place to find these families. SMS messages allowed for parents to check if their children were registered, but the system collapsed due to the huge number messages (Former Social Security Bureaucrat in Argentina 2020). After identifying the beneficiaries, the agency lacked enough debit cards to distribute so they could access the cash (Peronist politician involved in AUH 2020). These problems involving payments were immediately solved, however, and transfers started in November as promised.

But the rushed implementation generated serious issues in the control of conditionalities. There was no system to verify whether children attended school and went to the doctor. The targeting strategy also suffered from such a quick adoption. And the government ignored these problems, which did not affect the quick distribution of benefits—because these flaws did not affect CCTs’ popularity boost.

At some point later we cleaned our database and discovered that around 40 percent of the people had to be excluded. But it would be a political problem to expel so many people, so we had to change the rules just to keep them in. (Former Social Security Bureaucrat in Argentina 2020)

Takeaway from CCTs

The foregoing descriptions show that presidents in both countries had similar reasons to fast-track the policymaking of CCTs. The two presidents dire political situations that threatened their popularity, and they expected CCT stipends to boost their popular support. In response, these rulers rushed the enactment and implementation of the model, acting unilaterally to accelerate the policymaking process and ensure that the new programs were only attributable to the executive.

Other countries in the region suffered the same political weakness present in Argentina and Colombia. In some of them, enactment followed protests and a decrease in the president’s popularity. Guatemala’s Álvaro Colom enacted CCTs amid peasant protests and ministerial disputes (Solis Reference Solis2008, 14–21) after his popular support plummeted almost 20 percentage points. Similarly, Miguel Ángel Rodríguez adopted CCTs in Costa Rica at the worst of his popularity, after protests against a privatization plan took over the country (La Nación 2000). These situations did not cause CCTs’ diffusion surge because they were not present in most adoptions across the region. Still, the political weakness magnified presidents’ concerns about their popularity in these countries, which highlights the importance of presidents’ expectations that the model would boost their popularity.

Moreover, as did Kirchner and Pastrana, multiple presidents took a top-down approach to CCTs. In Chile, the president’s decision to immediately implement the policy in 2002 cut off bureaucrats already working with the World Bank to adapt policies into the model in 2003 (Ruz and Palma Reference Ruz and Palma2005, 25). Presidents across the region also controlled CCTs’ implementation tightly (Osorio Gonnet Reference Osorio Gonnet2020, 100). In Paraguay, Nicanor Duarte directly led the Gabinete Social responsible for the policy (Rivarola Reference Rivarola, Cohen and Franco2006, 374). This hands-on approach ensured a rushed implementation to deliver payments as quickly as possible, but as highlighted above, it also caused design problems in other aspects of the programs.

PPPs in Colombia

If Familias en Acción was a rushed solution to plummeting popularity, the adoption of public-private partnerships followed Colombia’s normal enactment and implementation processes. Colombia’s specialists started discussing PPPs in 2006, but the idea did not resonate with then-president Álvaro Uribe. Juan Manuel Santos’s campaign in 2010, promising to revitalize the country’s roads, brought the model out of specialized debates. Once elected, his cabinet started to work toward the adoption of PPPs, a process completed only in 2013.

Politicians and bureaucrats specializing in infrastructure described having heard the idea of a new framework for projects during Uribe’s government (Member of Santos’s Cabinet 2019; Colombia’s PPPs Bureaucrat #1 2019; Colombia’s PPPs Bureaucrat #2 2019; Former Ministry of Transportation Bureaucrat 2019; Colombia’s PPPs Bureaucrat #3 2019). But at the time, members of the cabinet rejected the policy, and the president had different priorities.

In Uribe’s government, this would not pass because he was a populist. (Member of Pastrana’s and Santos’s cabinets #3 2019)

We spent two years explaining the model, with a lot of resistance. (Colombia’s PPPs Bureaucrat #3 2019)

The minister of transportation was not interested. He used them [construction projects] politically. (Colombia’s PPPs Bureaucrat #1 2019)

Debates about PPPs moved into macropolitics only when a new president placed infrastructure on the political agenda. Santos’s government plan stated that “just like the United Kingdom, Brazil, and Costa Rica among others, we will promote private entities that structure projects” (Santos Reference Santos2010). After taking power, he immediately started discussing the idea of PPPs (Member of Pastrana’s and Santos’s cabinets #2 2019; Colombian Economist and Consultant for PPPs 2019). Yet despite all that interest, the innovation was not rushed. Previous presidents unilaterally enacted multiple changes in infrastructure policy using CONPES documents, the same tool applied to create CCTs in 2000. The most notable case was CONPES 2597 of 1992, which established the legal framework for Colombia’s first generation of concessions for highways.Footnote 15 Nevertheless, Santos decided to enact PPPs through Congress. Cabinet members established a dialogue with congress members, governors, and mayors to design the policy (Ex-member of Cámara Colombiana de Infraestructura #2 2019).

I included a lot [of what they had to contribute]. I believe that if someone provides an idea, even if it is not helpful, if it is not harmful, it is better to include it. That helps you move forward. The discussions were technical and good. (Member of Santos’s cabinet 2019)

Representatives of business interests also participated in these debates with the government.

They [government representatives] heard the CCI [Cámara Colombiana de Infraestructura] a lot and included many requests from the market. This was evident in the large number of private projects [proposed by private companies after the law passed]. (Former Bureaucrat at Agencia Nacional de Infraestructura 2019)

It took 15 months for the government to present the bill in Congress. The enactment process there was quick, and even leftist politicians and organizations accepted the policy.

I think the left did not fully understand it [the model]. Privatizations bother labor unions, but PPPs do not cost them anything. They are new projects and do not affect what is already in place. (Member of Pastrana’s and Santos’s cabinets #1 2019)

With the law approved, new debates started on its regulation and implementation, involving construction companies, investment funds, and banks (Ex-member of Cámara Colombiana de Infraestructura #1 2019; Colombia’s PPPs Bureaucrat #3 2019). These dialogues ensured that stakeholders were heard and their concerns were addressed.

As opposed to the rush to implement CCTs, it took 22 months before the government presented the first PPP project to potential investors. Instead of quick, immediate implementation, bureaucrats worked carefully on the largest infrastructure plan for transportation in Colombia’s history. This enormous project involved almost five thousand miles of roads. Private partners signed the first contracts for part of the project in 2014.

PPPs in Argentina

As in Colombia, PPPs in Argentina depended on presidents’ actions. The model had been well known since the early 2000s, when President Néstor Kirchner signed a decree for the National Regime of Public-Private Associations in an attempt to attract private investments. However, the decree was considered an imperfect version of the model (Drafter of the PPP law in Argentina #1 2020), and the country’s recent default meant the risk was too high for the policy to advance.

[Néstor] Kirchner tried, but that was still a period of adversity for the economy. (Argentine Consultant specializing in public services 2018)

It was the time after the default … and with that huge risk, it was not worth it for investors. (Drafter of the PPP law in Argentina #1 2020)

Interest groups lobbied for the implementation of PPPs in the following years, but President Cristina Kirchner ignored them.

All our efforts to advance PPPs [during that period] were useless. (Member of Cámara Argentina de Construcción 2018)

They had to wait until 2015, when Mauricio Macri defeated Peronism in presidential elections, promising a boost in infrastructure (International Consultancy Member in Argentina 2020; Argentina’s PPPs Office Lawyer #2 2020), and brought PPPs back on the stage. As expected, adoption this time followed a slow and careful process (International Consultancy Member in Argentina 2020). It started right after Macri came to power, when the government invited an association of lawyers to draft the bill. This group made sure all actors and stakeholders had their interests accommodated.

It [the draft] was sent to large consultancy firms and to the Construction Chamber. To all actors involved in funding and banking. All these actors made comments that were considered.… And from there came the bill sent to Congress. (Drafter of the PPP law in Argentina #2 2020)

As in Colombia, the government invested time and effort convincing congress members. The left did not oppose the bill in Congress or on the streets.

Even though it was from Macri, the policy had support from many political forces. Even those in opposition.…There was no pitched battle, as was the case in other laws. (Argentina’s PPPs Office Bureaucrat #2 2020)

The opposition was reasonable.… There wasn’t a strong ideological resistance. Once we explained the law, they understood it. (Drafter of the PPP law in Argentina #1 2020)

Congress approved PPPs in Argentina in November 2016. Half a year later, in May 2017, the government had its first meeting about projects for PPPs, and there was still no team to work on them (Argentina’s PPPs Office Bureaucrat #2 2020; Argentina’s PPPs Office Lawyer 2020). The government presented its first project only in November 2017: a mishmash of six old road construction plans (Argentina’s PPPs Office Lawyer 2020). Not rushed to implement the projects, the government once more consulted with foreign groups and organizations.

The project of highways had inputs from everywhere.… We discussed each step with all actors, and they nourished it enormously. (Argentina’s PPPs Office Lawyer 2020)

Such a long process ended up defeating the policy. Macri started the policymaking process at the beginning of his mandate, with an improving economy and congressional support. At the end of 2017, the economy was starting to fall apart and Congress had turned more reactive. The crisis scared investors away and killed Argentina’s PPPs (Argentina’s PPPs Office Bureaucrat #2 2020; International Consultancy Member in Argentina 2020; Argentina’s PPPs Office Lawyer 2020; Infrastructure Specialist in Macri’s Cabinet 2020). A fast-track adoption could have ensured the policy’s survival.

Takeaway from PPPs

Unlike CCTs’ adoptions, it is clear that presidents took their time to design PPPs carefully. While they enacted CCTs unilaterally, ignoring social actors, opposition parties, and even allies in Congress, they enacted PPPs through negotiations and inclusive debates. The same approach was present in implementing the model: specialized bureaucrats had time to develop the projects before presenting them to potential investors. More importantly for hypothesis 2, these adoptions were not motivated by an immediate expectation of popularity. Instead, they were focused on solving a policy issue—the need for infrastructure development—on which both Macri and Santos had campaigned.

Conclusions

This article has explained why the conditional cash transfer model has diffused so quickly to most Latin American countries, in contrast to policies that diffused at more common rates, like public-private partnerships. The argument defines diffusion as a two-step process: first, information about how a policy spreads; second, government’s adoption of the model in each domestic setting. While the literature centers on the first step, this research has looked at the second one.

The argument explains that presidents’ limited attention gravitates toward policies that provide immediate benefits to many people, like CCTs, which are expected to generate gains in popularity. Because all governments need popular support, most executive leaders use their policymaking powers to pull these policies from specialized debates, quickly enact them by decree, and rush their implementation. The aggregate result of these hasty adoptions is a diffusion surge. Policies that are not expected to immediately increase approval ratings, like PPPs, can still be interesting to some presidents, but they are not interesting enough to justify fast-tracking their adoption. The diffusion following these slower adoptions is a typical wave.

The process-tracing analysis yields striking findings, confirmed by the in-depth cases of Colombia and Argentina. These results show that domestic political dynamics deserve more attention in the study of policy diffusion because the simple spread of information is insufficient to explain why some policies are adopted faster and by more countries than others. The institutionalized process of policymaking constrains the adoption of policy models from abroad. Presidents select which models they will fast-track and which ones they will adopt in a longer policymaking process that goes through the legislature and that does not rush bureaucrats in the implementation stage.

This article has explained CCTs’ surge in Latin America, expanding on the importance of democratic competition for the spread of this policy highlighted by previous studies (Brooks Reference Brooks2015; De La O Reference De La2015; Díaz-Cayeros et al. Reference Díaz-Cayeros, Estévez and Magaloni2016; Garay Reference Garay2016). But the article has also illuminated adoption dynamics for other policies. My argument sheds light on diffusion patterns for any readily available model that can generate substantive gains in approval ratings. This would be the case for most models that allow for fast distribution of money to poor people, like emergency social funds (Graham Reference Graham1992).

As for policies that do not immediately affect popularity, a focus on the preponderance of the executive in policymaking also enables a better understanding of diffusion processes, depending on how they affect the interests of the government in place. The case of PPPs shows that the policy only grabbed the attention of presidents already interested in infrastructure, and even those presidents did not use extraordinary powers to adopt the model quickly. My argument predicts that other policies that address specific concerns without generating immediate popularity boosts will diffuse in a wave similar to that of PPPs. This would be the case of models like pension privatization reforms (Weyland Reference Weyland2006). Overall, the key role of the executive in the domestic dynamics of policy adoption is crucial to understand how models diffuse across countries.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/lap.2023.30