Does legislative behavior of representatives vary as a function of their social background and group membership? Should variation in collective interests, preferences, and identities affect individual-level performance, even under similar party constraints? These questions are not new in contemporary political science, and have nurtured multiple approaches to the study of race, ethnicity, and gender. Specifically, contributions on how constitutive components of social identities (being a Latino, an African American, an Asian, or a woman) make a difference over legislative performance are plentiful. However, to date, studies exploring how belonging to other social groups may affect individual-level behavior in legislatures have been more the exception than the rule.

With this realization in mind, this article focuses on workers, a social group that has been analyzed in the literature on party formation, democratization, and development but is largely missing from the literature on legislative behavior. Specifically, this study deals with the empirical behavior of representatives with a background in labor unions, relying on the intuition that they should care about the preferences of their social classes of origin in their legislative activities.

It is common wisdom that labor parties have spread across the world from the nineteenth century on, bolstering expectations of worker-centered behavior. However, it is also known that labor unions tend to be fundamental components of populist parties, which are more heterogeneous and broader in their electoral appeals. Given their all-encompassing and assorted targets, populist leaders and their parties have attempted to include dissimilar groups in their structures. In such organizations, workers have played a substantive role and have become frequent targets of discourse, platforms, and policy proposals. Nevertheless, it is not clear that these parties, even with a strong proworker rhetoric, will ultimately concentrate their legislative tasks on the development of policies targeted toward labor.

Similar doubts can be cast on the behavior of representatives with explicit links to labor organizations. What should their main course of legislative action be? Should representatives with labor ties concentrate their efforts to represent their group of reference, even amid party pressures? Should they be the only ones who care about labor? Should only affiliates of the party that claims labor representation use time and resources to target workers? These questions motivate the current analysis, wherein the performance of legislators in Argentina with a labor background will be assessed.

Argentina is an ideal case for such an analysis, given that parties with and without explicit ties to labor have attempted to develop connections to gather workers’ votes and that the party organizations with ties to labor unions are also expected to represent other social groups. As is widely known, Argentine politics has witnessed the rise and persistence of the Justicialista Party, an organization heavily anchored in the image, ideas, and legacy of its founder, Juan Perón. Its appeal hinges on the defense of the poor and the deprived, but it is also historically linked to labor unions. However, appeals to workers have not been restricted to the Peronists. In fact, Argentina has a Socialist Party, a middle-class–oriented Radical Party, and several center-left parties, in which different branches of organized labor have participated. Considering the important share of legislators with labor background in recent decades (11 percent) and oscillations in the policy orientation of most parties (including the populist), the Argentine experience is a fruitful case for the analysis of variation in the labor-oriented behavior of its representatives.

Through an analysis of about 120,000 bills drafted between 1983 and 2007 and the creation of a database of legislators’ individual backgrounds, this study explores whether representatives with participation in labor unions systematically have pursued the defense and promotion of workers’ rights in their legislative tasks. Results show that deputies with ties to labor organizations tend to draft twice as much legislation pertaining to workers’ rights as the rest of their colleagues. However, contrary to expectations, such an increase is irrelevant to the membership of Peronism. The behavior of non–union-linked Peronist legislators is more similar to that of non-Peronists without labor ties than to their Peronist copartisans. A possible interpretation is that there was, in fact, a division of labor within the party. However, due to the strength of the effect in very dissimilar parties, it can also be concluded that group membership is a stronger proxy for bill drafting than parties in this specific case.

This article contributes to the understanding of representation of very different groups from those analyzed in the mainstream literature. It also provides evidence about how dissimilar factors foster behavior beyond party lines without necessarily making leaders angry. Such findings open a space for deeper analyses of the impact of other identities and group references on congressional performance, and trigger new discussions on the impacts of the complex relationship among individual interests, collective cues, and party pressures on public activities.

Representation of Social Groups and Congruence

Multiple studies in the literature have assessed how group identity can affect different patterns of political activity. Specifically, during the last decade, a considerable part of the discipline analyzed the institutional devices designed to further descriptive representation of marginalized groups (Htun Reference Htun2004; Jones Reference Jones2009; Franceschet et al. Reference Franceschet, Krook and Piscopo2012) and the extent to which their presence implied substantive benefits for their peers (Cameron et al. Reference Cameron, Epstein and O’Halloran1996; Barreto et al. Reference Barreto, Segura and Woods2004; Minta Reference Minta2009; Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2010, among many others).

Empirical contributions have analyzed patterns of behavior by legislators who are members of marginalized groups with strong identities and common past afflictions. Studies have shown that the presence of delegates of the same ethnicity is positively correlated with the development of trust (Abrajano and Álvarez Reference Abrajano and Álvarez2010), increases in turnout (Bobo and Gilliam Reference Bobo and Gilliam1990; Barreto et al. Reference Barreto, Segura and Woods2004), confidence in representatives (Banducci et al. Reference Banducci, Donovan and Karp1999), and joint cosponsorship of bills (Bratton and Haynie Reference Bratton and Haynie1999; Whitby Reference Whitby2002; Rocca and Sánchez Reference Rocca and Sánchez2008), among other results. Additionally, scholars studying gender and politics have demonstrated that increases in the share of female legislators are associated with the promotion of policies for women (Schwindt-Bayer Reference Schwindt-Bayer2006, Reference Schwindt-Bayer2010; Franceschet and Piscopo Reference Franceschet and Piscopo2008; Htun et al. Reference Htun2013), increases in their bill cosponsorship (Barnes Reference Barnes2016), and development of constituency service for their gendered bases of support (Norris 1996; Friedman Reference Friedman2000).

As can be observed, the mentioned groups tend to cluster subjects along fixed sociodemographic characteristics that can be used as focal points for social identification. Nevertheless, perceived group membership can also depend on other socially constructed sources of distinction that may rely on material conditions, common attributes, or similar preferences. Beyond discussions on whether these groups can be substantively represented; nothing prevents them from being heuristics for voters and legislators to develop representational links and expectations of policy congruence.Footnote 1

Little empirical work exists that examines the behavior of legislators from marginalized groups aside from race, ethnicity, and gender; however, there are some exceptions. Some authors demonstrate that “the poor” can be identified as a social group for representation and legislative activities. After discussing the difficulty of conceptualizing class in empirical studies, Carnes (Reference Carnes2013) links the occupational background of legislators with their degrees of liberalism or conservatism. His findings reinforce the idea that poverty, as a social category, tends to affect ideology. Taylor-Robinson (Reference Taylor-Robinson2010) also takes the poor into account to assess patterns of representation in the Honduran Congress. Linking poverty with a lack of elementary education, Taylor-Robinson emphasizes the difficulties these subjects face in monitoring the fulfillment of their symbolic and material representation.

Carnes and Lupu (Reference Carnes and Lupu2015) also bring social class to the fore and reliably demonstrate that variation in occupational background affects the economic attitudes that legislators take to assemblies. Similarly, Griffin and Anewalt-Remsburg (Reference Griffin and Anewalt-Remsburg2013) find links between social class (wealth) and a legislator’s willingness to block estate taxes, while it has also been shown that members of congress with business backgrounds tend to behave more in line with firms’ interests (Witko and Friedman (2008). From a different perspective, Bianco (Reference Bianco2005) demonstrates that a military background affects legislators’ voting decisions on defense and foreign policy issues. Burden (Reference Burden2007) finds that religiosity is a strong predictor of behavior toward bill drafting on human cloning, religious freedom, and charity.Footnote 2

If there were ever a social group that has been recognized as a relevant political actor with self-awareness, it would be workers. As a predominant component of most societies from the late nineteenth century on, this group has offered multiple instances of workers’ organizing to fix an apparent contradiction: a social class that tended to be at least the plurality group of almost every country whose material conditions made it a subaltern one.Footnote 3

Therefore, workers coordinated efforts and gave birth to class-based parties that fought for their liberation and the implementation of proworker policies. Following the notion of descriptive representation, we should observe many working-class members occupying seats in parliaments and congresses once labor parties have been empowered. Given the bottom-up organization of workers, it would be reasonable for their delegates to public office to be heads of labor unions. Descriptive studies (e.g., Norris and Lovenduski Reference Norris and Lovenduski1995) show that this supposition holds true. What we do not fully know yet is whether legislators from labor parties have truly been champions of the group’s cause.

Labor Parties and Workers’ Representation

Most sociological contributions on party formation have highlighted the role of social divisions, which have defined the sources of political conflict in different historical circumstances. Following Lipset and Rokkan’s seminal approach (Reference Lipset and Rokkan1967), four cleavages have divided occidental societies from the nineteenth century on, the labor-capital dichotomy being the primary and most widespread determinant of the creation of party organizations. Observing the growth in the number of workers in industrial societies, members of the labor sector promoted their organization in unions, which became the basic units for the development of political parties (Przeworski and Sprague 1984). Following this genesis, labor parties were, in their European origins, the exclusive and exhaustive mechanism for transmitting the interests and ideas of workers.Footnote 4 In line with workers’ progressive expansion in politics, their prevalence was perceived as inevitable in the medium run, and the promotion of their social rights a certain fact (Przeworski and Sprague 1984, 5).

However, beyond the undeniable growth of the labor force in industrial societies, there is another demographic truth with deep political implications: workers have never become a majority in any occidental country. The prospective success of their political claims was not just a function of organization and union. Compromises with other social groups and sectors was a necessary condition for their success.Footnote 5 Labor parties’ main dilemma became whether to open their platforms and ideas to other social groups, at the supposed expense of betraying their foundational demands. In fact, most labor parties opted to transform to “the party of the ‘people.’ Its appeals are no longer addressed to the manual workers, but to ‘all producers,’ to the ‘entire working population” (Przeworski and Sprague 1984, 41).

When they attempt to expand their political appeal, labor parties may need to alter their legislative behavior. If labor parties expected to broaden their electoral bases, their observed activities might not have been restricted to the improvement of the living conditions of the working class. Thus, a broader set of policy proposals should be recognized in the legislative activity of labor party members. Labor party delegates in public office should not necessarily belong to “workers” as a social group, nor should they be members of labor unions. Even the empirical activities performed by members of the purest labor party with serious electoral expectations might not be fully devoted to the representation of workers’ interests. Consequently, their expected behavior is still full of uncertainty.

Such ambiguity would be enhanced in scenarios in which the representation of labor has traditionally relied on parties that targeted workers and incorporated labor unions, as well as other, more diversified bases of support. In other words, it would be harder to define clear expectations for the individual and collective behavior of parties to which workers serve as just another group of reference.

Populist Parties and Workers’ Representation

Numerous works in the literature have dealt with the definition, recognition, and characterization of the controversial term populism. Far from reaching a consensus, scholars have largely failed to develop a generally accepted conceptual definition to understand a plethora of dissimilar leaders, parties, and movements.Footnote 6 Several common patterns have been recognized, such as a top-down mobilization, the appeal to the so-called subaltern groups (the poor, the excluded, and the marginalized), the development of a noninstitutionalized relationship between the leader and the masses, and the redistribution of material resources from the top of the state (Roberts Reference Roberts1995; Weyland Reference Weyland2001).

Based on the recognition of this multiclass coalition, behavioral expectations of the political and legislative performance of populist party members are diffuse and uncertain. If top-down dynamics remain in place, it could be argued that policy mandates defined by the leader of the party or movement should be honored by any single member and thus find no significant variation within the party delegation. However, members of each constitutive group, including workers, might want to capitalize on public activities on behalf of their bases, and therefore behave in a dissimilar manner. This is one of the main puzzles examined here.

In Latin America, most parties traditionally labeled as populist have incorporated organized labor. Studies analyzing the Mexican PRI (Langston Reference Langston2003, Reference Langston2017), the Venezuelan Acción Democrática (Coppedge Reference Coppedge1997; Crisp Reference Crisp1997), the Peruvian APRA (Graham Reference Graham1992; Burgess and Levitsky Reference Burgess and Levitsky2003), and Argentine Peronism (McGuire Reference McGuire1997; Levitsky Reference Levitsky2001) have illustrated the historical role of labor unions in the organization, funding, decisionmaking, and electoral power. On the basis of that observation, it seems reasonable to expect that policies, activities, and even symbols of these parties should tend to reflect the strong participation of this organized sector. However, it is important to remember Levitsky’s depiction of these organizations as having “more heterogeneous support bases, as they included elements of the unorganized urban and rural poor, the middle sectors, and, in some cases, the peasantry . . . and their ideologies were generally amorphous or eclectic, rather than Marxist or social democrat” (2003, 22). Therefore, it is not clear that workers should (or will) be genuinely represented by those parties that include their specific organizations.

The mixed theoretical expectations demand empirical verification. Following several influential contributions (Levitsky Reference Levitsky1998, Reference Levitsky2003), there is a case that fits perfectly the assessment of the questions raised: the Argentine experience after its democratic restoration in 1983. As a country dominated by a populist party anchored in labor unions (Peronism) for decades, Argentina has a significant share of representatives who have a background in workers’ associations. Even though most of those legislators belonged to Peronism, others were nominated by different parties. Peronist representatives also included delegates recruited from other sources, such as business associations, religious groups, agricultural organizations, or local leadership roles.

As another interesting source of variation, most labor unions remained loyal to Peronism even after the neoliberal turn it took in the 1990s, while a minority of organized labor split off and joined other parties and movements. This scenario provides an interesting setting to verify whether the party and the individuals with ties to unions have, in fact, been the ones who concentrated the pursuit of interests of the working class.

Representation, Labor, and the Peronist Party

It is known that Peronism has long been the dominant force in Argentine politics. As extensively depicted by Levitsky (Reference Levitsky1998, Reference Levitsky2001, Reference Levitsky2003), the Justicialista Party was created by a colonel who established a direct relationship with his pueblo. The organization was shaped as a labor-based, mass populist party characterized by “a massive national organization, large membership and activist bases, and strong linkages to working and lower classes” (Levitsky Reference Levitsky2003, 22). This synergy did not just rely on people’s emotional attachment to the policies implemented by Juan Perón and his wife Evita in the 1940s and 1950s, but also was boosted by the many benefits gained by labor unions, such as bargaining power with business leaders, collection of onerous union dues, and management of funds for social services (such as the provision of health care or the ownership of hotels and recreational facilities).

Moreover, one of the best indicators of such relevance was the so-called tercio, an informal institution that granted labor unions the right of nominating a third of the candidates for every Peronist list. Thus, many candidates with a background in workers’ organizations won seats in the federal congress, state legislatures, and even governorships and municipal executives. With such strength, union leaders became integral to the day-to-day functioning of the Peronist machine.

After the dictatorship between 1976 and 1983, the democratic restoration saw the reconstruction of Peronism (without its founder) following the same historical paths: a vertical leadership formally occupied by Perón’s widow and a strong influence of labor union leaders. The image of violence and thuggery, along with complaints about a pact with the fading military regime, prompted the Peronists’ first-ever electoral defeat in free and fair elections and triggered several realignments. A new faction, more modern and less attached to workers’ organizations, Renovadores, took control of the leadership and attempted to transform it into a social-democratic party. One of the first consequences of this change was a decline in the share of workers’ delegates in the House, because of the demise of the 33 percent party quota.

However, the biggest change was yet to come. After the neoliberal digression led by president Carlos Menem (1989–99), new alignments took place at the electoral, organizational, and coalitional levels. While most labor unions remained under the Peronist Party (and government) banner, some decided to denounce the betrayal of the workers’ cause, split from Peronism, and create new center-left organizations (see Garrett and Way Reference Garrett and Way1999; Murillo and Ronconi Reference Murillo and Ronconi2004). These included public sector organizations like teachers or state bureaucracies.Footnote 7

For this main reason, the realignment reshaped opportunities and challenges for the representation of workers. On the one hand, the presence of unionists in the lists of these new forces opened a space for the maintenance of descriptive representation. On the other, after the Peronists’ turn away from workers, there was space for other parties to try to attract workers’ votes. Argentina’s Socialist Party has relevant strength in urban districts, and its Radical Party has a center-left orientation and ties with middle-class–oriented labor branches (i.e., insurance or banking services). Furthermore, the Peronists’ new orientation may have led members to discard the emphasis on labor representation, thereby diminishing the activities performed by the party delegation in Congress. For these reasons, our knowledge of workers’ representation is still scarce, and deserves empirical evaluation.

Table 1 shows the changing shares of labor union delegates occupying seats in Congress. As expected, the return to democracy showed the peak in the trend, with declining rates thereafter. The number of delegates remained relevant enough to speculate about patterns of behavior centered on the representation of this social group. However, a brief review of the literature on the Argentine Congress may discourage the assessment of those behavioral trends. Specifically, scholarly work (Jones et al. Reference Jones2009) shows that government-opposition has always been the main dimension dividing voting patterns in the Chamber, findings reinforced by the realization of strong party discipline (Jones Reference Jones2002) and cartelization (Jones and Hwang Reference Jones and Hwang2005; Calvo Reference Calvo2014). Therefore, there should not be a space for variation following other lines, including gender, region, or any other group membership.

Table 1 Number and Share of Deputies with a Labor Union Background, First 12 Congresses

Source: Compilation based on Directorio Legislativo, interviews, and newspapers

Nevertheless, it is well known that final passage votes are neither the only nor the most reliable indicator of congressional performance. Other work points out that variation in individual-level behavior can be found in different activities, bill drafting being one of the most salient ones, as it lets representatives send personalized signals to constituents, donors, and leaders without necessarily breaking party mandates. This is the use of the so-called non–roll call position-taking devices (Highton and Rocca Reference Highton and Rocca2005), which triggers representation as a process (Franceschet and Piscopo Reference Franceschet and Piscopo2008).

Contributions along this line can also be found in the literature on the Argentine Congress. In fact, elsewhere (Micozzi Reference Micozzi2014a) I show that the drafting of bills centered on local districts is used as a tool for personalization, especially by legislators with subnational executive ambition. Franceschet and Piscopo (Reference Franceschet and Piscopo2008) and Htun et al. (Reference Htun2013) demonstrate how bills written on women’s rights increased as the share of female representatives grew in both chambers. Highlighting another dimension, Micozzi Reference Micozzi2014b shows that cosponsorship is more frequent among deputies with similar short-term career expectations. As discussed above, the introduction of bills centered on a specific group is likely to be a valid indicator of attempts to represent its members, as extensively documented in comparative settings.

Hypotheses, Data, and Estimations

Even though causal relations may involve mixed expectations in the case of labor union–linked legislators, several hypotheses can be formulated for empirical verification. If notions of group representation are accurate, individuals who have been recruited from organized labor should be more active in promoting workers’ interests and preferences. As discussed, we interpret such behavior as increases in legislative activities targeted toward their group.

H1. Deputies with a background in labor unions are likely to submit more bills promoting workers’ rights.

Despite the alleged multitarget strategies pursued by the populist party, it can be assumed that its proworker rhetoric makes its members more likely to bias their congressional tasks toward that social group. Therefore,

H2. Deputies who belong to the Peronist Party are likely to submit more bills promoting workers’ rights than any other party.

If background makes a difference, and thereby so does party membership, we should find a higher likelihood that those Peronist deputies who also are labor union members invest more time and resources to represent workers. Hence, an interactive hypothesis is included.

H3. Deputies who belong to the Peronist Party and have a background in labor unions are likely to submit more bills promoting workers’ rights.

Furthermore, Peronism is not the only organization that attempts to represent workers. Therefore, we expect other parties’ members with a proworker rhetoric not to be indifferent to that social group in their legislative tasks, but to pay attention with a lower intensity than Peronists.

H4. Deputies of the Radical and Center-Left Parties are likely to submit more bills promoting workers’ rights than the baseline, but still less likely than their Peronist colleagues.

To test these hypotheses, I constructed an extensive database in which the unit of analysis is every single bill introduced to the Argentine House between 1983 and 2007.Footnote 8 Observations number 117,007 and include information on sponsorship, district, party, and tenure of the author(s); committees that dealt with each bill; the outcome; and a detailed, one-paragraph description of the content of each bill.

Activities on behalf of workers are measured as the submission of bills that highlight the interests and rights of labor as a group. Scholars have employed numerous indicators of activities denoting congruence and responsiveness with specific sets of voters, such as share of local bills submitted (Gamm and Kousser Reference Gamm and Kousser2010), number of speeches (Rocca Reference Rocca2007), amendments offered to relevant bills (Cook Reference Cook1986; Hibbing Reference Hibbing1986), responses to newsletters (Butler et al. Reference Butler, Karpowitz and Pope2012), credit-claiming messages (Grimmer et al. Reference Grimmer, Messing and Westwood2012), and trips to home districts (Crisp and Desposato Reference Crisp and Desposato2004). This study uses one of the most utilized dependent variables in the literature, the number of targeted bills submitted by a legislator in a given period (Schlesinger Reference Schlesinger1966; Van Der Slik and Pernacciaro Reference Van Der Slik and Pernacciaro1979; Ames Reference Ames2001; Crisp et al. Reference Crisp, Demirkaya, Schwindt-Bayer and Millian2018; Alemán et al. Reference Alemán, Micozzi and Ramírez2018). Even though mandates are four years long, the temporal unit is a Congress (2 years), as partial renewal by halves makes periods very different, both in terms of political context and in the priorities taken by each representative.

Because the dependent variable counts those bills whose content considers labor-related issues, measurement becomes a fundamental task. To filter bills in a reliable manner, I developed an automated coding strategy that, based on the recognition of keywords, classifies each bill in the sample as 1 if its title or summary includes a reference to workers’ rights, and 0 otherwise.Footnote 9 After several rounds of exhaustive manual review, 8,566 bills were used in the sample.Footnote 10

Several covariates are included in the righthand side of the equation. One of the most important ones in this study, a legislator’s background as a labor union member, bore several intensive challenges. The definition of a labor union became an issue, as the measure could have reflected multiple attributes, such as being a labor union leader, a mere affiliate to a labor union with a specific seniority, an individual formally nominated by unions, or simply a worker in an activity that is unionized. After analyzing the trade-offs of each alternative, I decided to code those deputies who were members of labor unions (regardless of hierarchy) as 1, and 0 otherwise. The identification process was not simple, as information was scarce for legislators who served more than 30 years ago. To make the classification as accurate as possible, I relied on historical recognitions previously made in the literature (McGuire Reference McGuire1997; Gutiérrez Reference Gutiérrez1998; Levitsky Reference Levitsky2003) and on Directorio Legislativo, a publication that has kept a record of individual-level information on every member of Congress since 2001.Footnote 11

Based on these sources, 129 deputies with background as labor union members were identified. I acknowledge that no criterion is optimal, nor the choice of indicators, but those utilized here are quite reliable, considering the status of the literature. As an example, Carnes and Lupu’s excellent work (Reference Carnes and Lupu2015) uses individuals’ previous employment to assess class. This sounds reasonable, but it is also doubtful that individuals with an occupation at time t (which might also vary across years) be mechanically a part of a social group. Moreover, several respondents to elite surveys like PELA report their occupation as “politicians,” which omits relevant background information.Footnote 12 Every measure and criterion has trade-offs. For the reasons pointed out, union membership seems a quite consistent (yet not perfect) identification proxy for labor membership.

Partisanship is also included in the models, as a necessary component for the empirical tests of the last three hypotheses. I specify variables for the Peronist and Radical Parties, Frepaso (a center-left coalition), other center-left parties (including Socialists), and strictly state-level parties (which compete only in one or a few districts).Footnote 13 As a reliability check, I include center-right parties in model 3 to take expected negative effects away from the baseline and see if results hold. In line with the idea that variation in the composition of the legislative delegation of a group affects behavior, I include a covariate measuring the share of workers each party bloc has in each period. Expectations bolster a positive effect for all but the state-level party covariates.

As controls for effects pointed out in the literature, I specify two sets of covariates. Representation of workers might be related to district-level effects, wherein variation in the share of group members is likely to affect legislative concerns. I include the share of workers in the home municipality of each deputy (the smallest environment with available information) as a control. Data are from 1991 and 2001 censuses, and the expected direction of covariates is positive.

Current literature states that ambition is a relevant predictor of targeted legislative activity (Schlesinger Reference Schlesinger1966; Crisp and Desposato Reference Crisp and Desposato2004). For this reason, I control for subsequent gubernatorial and mayoral candidacy, with the expectation that legislators with executive expectations may opt to target more voters of all kinds, including workers.Footnote 14 I also control for tenure, which reflects accumulated expertise that might affect bill-drafting propensities. Career-level information was gathered for Micozzi Reference Micozzi2014a.

Additionally, time is a relevant factor for the descriptive representation of workers, which might also affect bill-drafting patterns. In other words, if more labor union deputies used to win seats in the first postdemocratic restoration periods, it could be derived that more representatives (and their bills) would care about workers. It could also be counterargued that the smaller delegation that experienced neoliberal reforms used their seats as trenches and signaled the defense of workers in the bills they drafted. In order to control for this two-tailed expectation, I created two variables that capture fixed effects. The first one is coded as 0 between 1983 and 1991 (when the first cohort after the reforms took office), and 1 thereafter. The second takes the Kirchner administrations as non-neoliberal, and differs from previous one in that every year after 2003 is also coded as 0.Footnote 15

After creating the variables, I collapsed the information at the legislator-congress level and let my dependent variable be a count of the number of labor-related bills drafted by every deputy in that period. This decision left me a sample with 3,556 observations. Given the non-negative structure of the dependent variable, I used event count models for my estimations. I ran several regular Poisson models and, after testing for overdispersion, I concluded that the negative binomial distribution provided more reliable results. However, the abundance of zeros in the dependent variable (36 percent of the sample) persuaded me to utilize a model that calculates the outcome by mixing two component distributions, one for the zero-outcome portion of the equation and another for the positive values. Therefore, I decided to use the zero-inflated negative binomial model (Atkins and Gallop Reference Atkins and Gallop2007) and specify the total number of nonlocal bills submitted by legislator and congress as an exogenous regressor to predict the nonpositive outcomes.Footnote 16

Results

I ran four models to test the hypotheses. Specifications change by the sequential addition of the interaction between being a Peronist and a labor union member (model 2), the center-right bloc (model 3), and controls for ambition and tenure (model 4), and their outcomes are reported in table 2.

Table 2 Results of the Empirical Models

*** p < 0.01

** p < 0.05

* p < 0.1

Robust standard errors in parentheses

Legislators with a background in labor unions are systematically more likely to draft bills targeting workers than their non–union-linked colleagues. Coefficients are positive and significant in all estimations, providing support for the representation argument. Legislators with a labor background have dedicated time and effort to highlight the interests of their group of reference. Predicted outcomes computed in the first, noninteractive model show that, setting every other parameter to the mean, a deputy without a background in labor unions tends to draft 2.83 targeted bills per biennium, while a colleague with labor union connections writes 7.49 bills in the same timeframe. The size of the gap between groups strengthens the finding and bolsters the idea that the effect is genuine.

It could also be argued, however, that this effect is related to the division of tasks within parties. To validate this, we would expect a strong and significant effect by the Peronist Party (especially its labor members), as its solid compositional and temporal variation would make coordination and division of duties possible. Conversely, it would be harder for other parties with smaller delegations to allocate functional responsibilities in such a clear manner.

Party-level covariates show interesting results. Surprisingly, membership in the party that claims the monopoly of workers’ representation is negatively related with the systematic submission of bills targeted to workers. In every model, the coefficient shows a negative sign with extremely high levels of significance. At first glance, the temptation to ratify the populist nature of the movement and the subsequent dilution of workers’ representation would seem intuitive: a median Peronist is systematically less likely to draft a labor-based bill than a representative of a small party (omitted in the specifications), but also compared to the center-left, the Radicals and, very especially, Frepaso, a center-leftist party with urban anchorage. Following this interpretation, populism dilutes the expected proworker behavior at the aggregate level. To fully confirm this speculation, I tested the interaction between party membership and background as unionist.

Interactions are specified from model 2 on, and show systematically positive results. Beyond the reported statistical significance of the coefficient, the linear combination of every interaction and its constitutive terms shows that joint effects are significant. In concrete terms, those Peronists who are a part of workers’ organizations tend to draft more legislation in regard to their group of reference, in contrast to their other comrades. However, the effect is still indistinguishable from labor union deputies in other blocs.

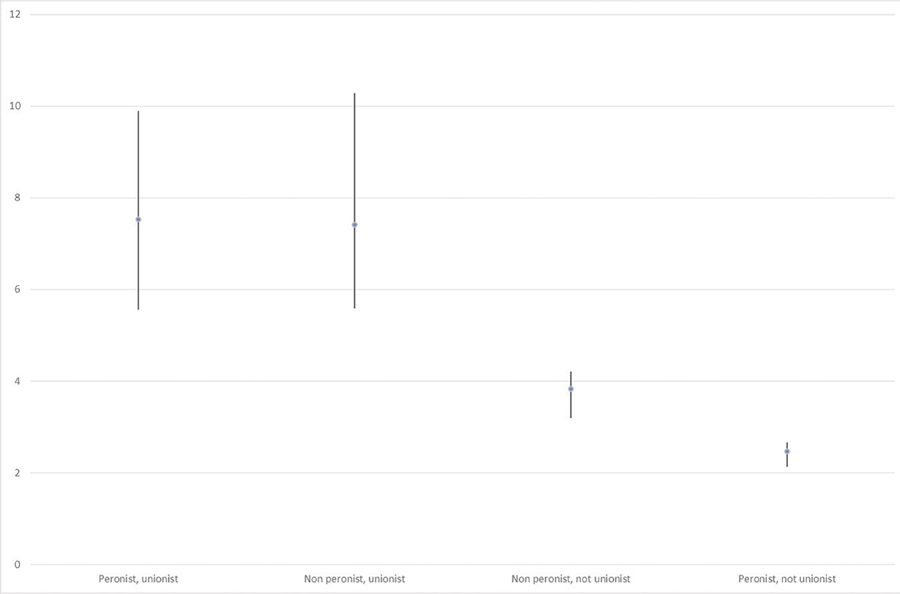

A summary of this discussion is shown in figure 1. The sharpest asymmetries can be found within the Peronist delegation: while deputies with ties to unions draft an average of 14 labor bills per their four-year mandate, every other Peronist tends to submit barely four in the same timespan. In parallel, labor union membership seems to pierce party-level boundaries, as is visible in the first two predictions at the left. In other words, partisanship does not make labor union members different in the statistical sense: all labor union members tend to behave in a similar manner, which distinguishes them from non–labor union members.

Figure 1 Predicted Number of Labor-Targeted Bills Drafted by Two-Year Period (by partisanship and labor union membership)

The finding that labor and nonlabor representatives of every party behave so similarly in this respect casts doubt on the idea of a coordinated division of legislative work. Would leaders of a three-member bloc be able to align prolabor tasks in exactly the same fashion as a powerful majority leader? My interpretation here gives more credit to the targeted representation story. In sum, labor was not divided but united in the defense of workers’ rights and interests through bill drafting.

Controls show an interesting performance across models. While the worker population in bill sponsors’ districts does not have a significant effect on legislative activities, both tenure and gubernatorial ambition do, at least marginally, in substantive terms. Far from contradicting the main findings, these covariates perform in line with what other work on Argentine legislative politics has found (Micozzi Reference Micozzi2014a), thereby adding coherence to the conclusions reached in the field. Furthermore, the size of the labor-based delegation in each party is negative and significant across models, suggesting that higher shares of workers might augment the contrast between the delegation’s legislative priorities and those of every other copartisan.

Finally, temporal controls are insignificant for these models but become significant for the corrected measure of neoliberalism reported in the online appendix, which favors the idea that workers use the drafting of bills as a (symbolic) defensive tool during hard times. This is, in my perspective, another piece of evidence of the representational goals achieved by legislators with a background as workers.

Discussion

Do workers represent workers? Do the organizations that have co-opted and rewarded labor unions tend to exhibit strong behavioral concerns in regard to the rights of this social group? The findings of this study demonstrate that descriptive representation of workers correlates with legislative production in Argentina. However, membership in the Peronist Party, the party with the most historical claims to the representation of workers, is not necessarily a strong predictor of congressional attention to workers. Instead, labor union membership is more important than, and independent of, partisanship.

Such findings can be interpreted in several ways, all of them with specific implications. The first is to consider whether theories suggesting that similarity in identity and shared interests in constitutive groups also hold for second-order organizations. This study shows that, similar to race, ethnicity, and gender, connections to workers as a social group positively influence legislators’ propensity to draft similar kinds of bills. This finding contributes to multiple literatures interested in the role of socialization and extends its impact over legislative settings, integrating two literatures that had not been frequently considered together. Another dimension to highlight is related to the concept of populism and the specific performance of a very successful case of electoral performance and adaptation, Peronism. The finding that only those legislators with ties to labor tend to develop congressional activities related to workers forces us reconsider Peronism’s recalcitrant prolabor rhetoric and understand it as what its founder originally envisioned: a broad and encompassing movement and an organization with a pragmatic orientation. As we have seen, no more than 16 percent of its congressional delegates belonged to workers’ organizations. Why should we expect a broad and general orientation to this group if it is not a labor party?

Such findings also open inquiries about the behavior of other organized groups that may also trigger social identification (i.e., farmers or small business owners). In this sense, an almost natural additional test of this argument is the analysis of the legislative performance of the Mexican PRI, whose historical organization was built on the basis of four main groups: workers, peasants, popular sectors, and the territorial structure (Langston Reference Langston2003). It would be of high interest to disentangle whether delegates of each of these subsets tended to forge representation of their original bases of support, beyond the party’s rigid pyramidal structure.

This study is the first attempt to recognize labor-based activities at the legislative level across and within parties in Argentina, paying special attention to the role of deputies with a background as labor unionists. Results are conclusive: social background as workers does make a difference in congressional bill drafting, beyond party membership. Interestingly, unlike what stories and mythical tales would suggest, the intermediation of Peronism is not a necessary condition for the representation of workers’ interests in Argentina.

Supporting Information

Additional supporting materials may be found with the online version of this article on the publisher’s website: Online Appendix, and on the author’s website: www.jpmicozzi.net.