Seals and sealings bear powerful implications for the development of protoliterate complex societies. In the Old World, sealings authenticated identity over distance and time (Platt Reference Platt2006) and represented social control by individuals or institutions (Gorelick and Gwinnett Reference Gorelick and John Gwinnett1990; Kenoyer and Heuston Reference Kenoyer and Heuston2005). Even today, we use idioms such as “imprimatur” or “seal of approval” and stamp, autosign, or emboss documents to convey their authenticity.

In the Indigenous Andes where graphic writing was unknown, communication at a distance involved symbolic objects (DeMarrais et al. Reference DeMarrais, Castillo and Earle1996) and textile technologies such as Inka tocapu and khipus (Eeckout and Danis Reference Eeckhout and Danis2004). Evidence for technologies that duplicated an impressed image is rare in New World civilizations, with examples known primarily from Mesoamerica (Pohl et al. Reference Pohl, Pope and von Nagy2002) and the northern Andes (Grieder et al. Reference Grieder, Farmer, Hill, Stahl and Ubelaker2009:111–127; Guffroy et al. Reference Guffroy, Baraybar, Cardozo, Carlier, Clément, Donzé and Emperaire1994:248; Tellenbach Reference Tellenbach1998:352).

The Tiwanaku civilization (AD 500–1100), one of the Americas’ earliest expansive polities, has been characterized as both a centralized hierarchical state and a pluralistic multiethnic heterarchy (Albarracin-Jordan Reference Albarracin-Jordan1996; Janusek Reference Janusek2004; Kolata Reference Kolata2003). As Tiwanaku expanded, attire and artifacts played an important role in relaying information about affiliation and politics (Baitzel and Goldstein Reference Baitzel and Goldstein2014). Tiwanaku's complexity suggests that there was some technology to transmit and authenticate identity or authority over distance, yet there has not been evidence for a duplicative medium comparable to Old World seals and sealings. Here we report on four objects found at the Tiwanaku type site and in Tiwanaku's Moquegua Province that constitute the first Central Andean evidence for impression sealing.

The Omo Sealing

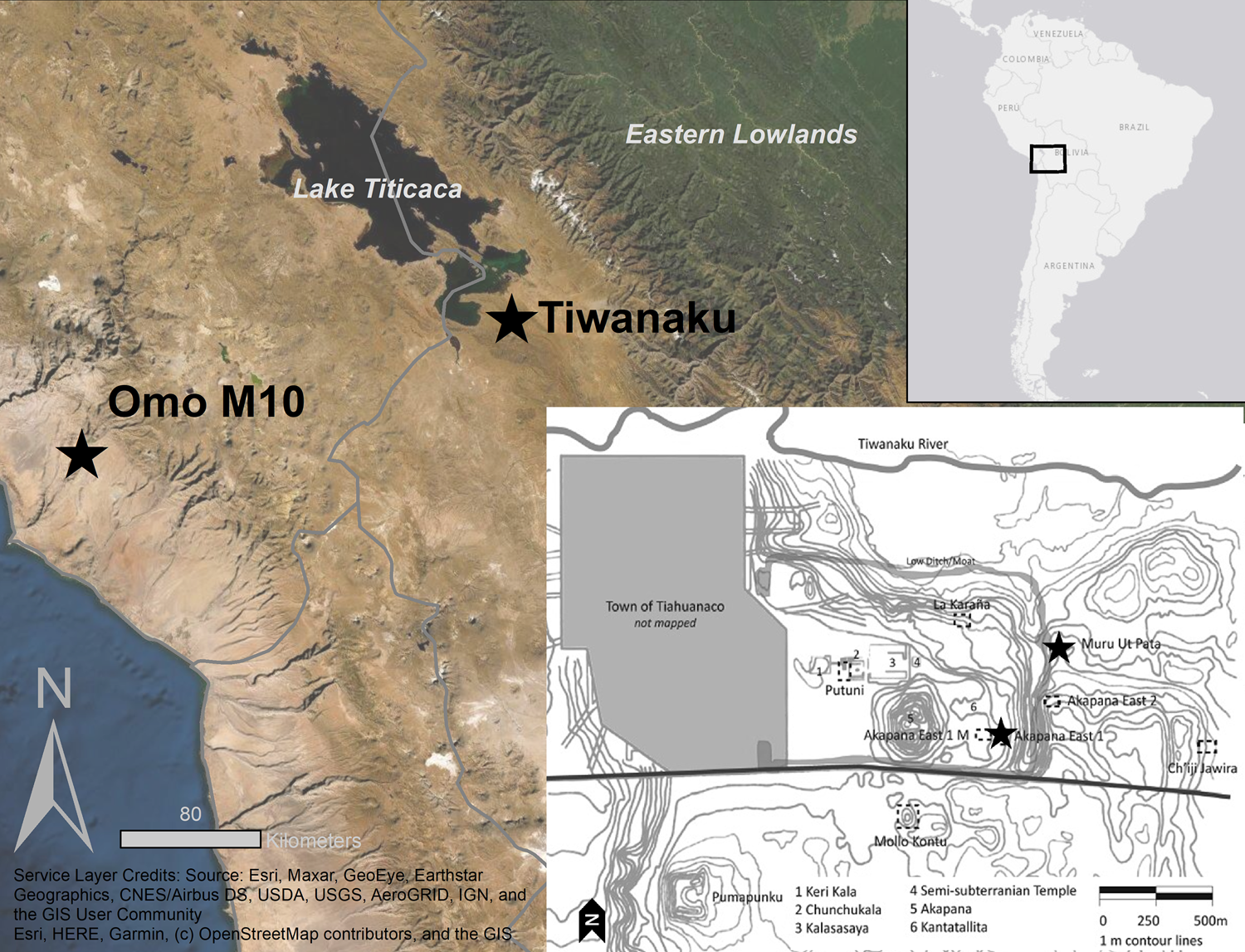

Omo (seventh to twelfth centuries AD) is a Tiwanaku enclave in the mid-altitude Moquegua Valley in Peru (Figure 1). Excavations exploring ceremonial architecture and activities at the Omo M10A temple structure (Goldstein and Sitek Reference Goldstein and Sitek2018) in 2011 recovered a sealing on a fragment of an irregular ball of dried clay 6.5 cm in diameter (specimen M10-12474; Figure 2a). On the back, the fragment has intersecting concave impressions (Figure 2b), perhaps from being attached to an architectural element or object made from cane. The sealing was found among architectural debris in temple room C18 (Figure 3), which may have functioned as a chapel of some subgroup within the temple complex. Ichu grass from level 13 of C18 dates the sealing's context to cal AD 893–992.Footnote 1

Figure 1. Location of Omo and Tiwanaku. Inset: location of Muru Ut Pata and Akapana East neighborhoods.

Figure 2. Omo sealing: (A) front, (B) back, and (C) design (photos and drawings by Paul S. Goldstein). (Color online)

Figure 3. Omo M10A temple reconstruction and room C18 (reconstruction and photo by Paul S. Goldstein). (Color online)

The Omo sealing is a subrectangular (15 × 17 mm) impression made in the wet clay. The central image, created in intaglio by an incised stamp that produced raised lines on the impression, depicts a right-facing zoomorphic head with a rectangular snout, decorated eye, ring nose, and ear (Figure 2c). The figure wears a tripartite headdress composed of an eagle plume, a crescent-shaped element resembling antlers, and a third unidentified element. Green pigment emphasizes the raised lines of the motif, suggesting that the incised design spaces of the seal had been filled with pigment before the seal was pressed into the wet clay; this produced pigmented raised lines on the sealing, as is common in intaglio. The green pigment of the Omo sealing awaits analysis but resembles pigment used for wall adornments and fugitive post-firing paint found on some incensarios at the site.

The profile-head figure on the Omo sealing resembles stylized profile-head representations in Tiwanaku iconography of a range of human, zoomorphic, and composite subjects. This version with curved antlers or horns most resembles a deer-head theme described as the “decapitator with deer antlers” found in Tiwanaku stone carvings, ceramic iconography, textiles, and bone artifacts (Trigo and Hidalgo Reference Trigo Rodríguez and Hidalgo Rocabado2018). The Omo sealing, however, does not include the disembodied limbs or head sometimes associated with the deer decapitator.

The Muru Ut Pata Sealings

Muru Ut Pata is a mounded area at the Tiwanaku type site located in the community of Kasa Achuta (Figure 1) outside the “moat” that is seen to delineate the monumental core of the site (Kolata Reference Kolata2003). During investigations in 2005 and 2006, broad horizontal excavation exposed more than 300 m2 in this domestic area (Davis Reference Davis2022). These efforts exposed a variety of production and ritual contexts, including occupation floors, ample evidence of feasting, burials, and trash pits, supporting a phase of urbanization outside the site “moat.”

Three radiocarbon dates for the Muru Ut Pata excavations correspond to a period late in the Tiwanaku occupation of the site (891–1024 cal AD, 2-sigma).Footnote 2 This dating is consistent with a reorganization of urban space in Tiwanaku IV–V during which some buildings within the core were ceremonially closed or razed and new occupations were established in previously unoccupied spaces like Muru Ut Pata (Janusek Reference Janusek2004). Muru Ut Pata ceramics consisted of Tiwanaku IV and V utilitarian and polychrome serving types, with few vessels from the eastern lowlands. The household assemblage—including ceramic forms and iconography, post-firing engravings on vessel bases, and camelid mandible polishers—resembles that of the Omo site.

Finds at Muru Ut Pata included two unfired clay “sealings” recovered from an ash pit in an interior patio (Figure 4). The impressions were made into wet clay that rested on an unidentified irregular surface, leaving grass-like marks on the back of the sealings. The sealings display two distinct motifs, both of which are contained in similar subsquare cartouches, approximately 3 cm in size. Both show an intaglio process: raised lines on the sealing that were produced by incised grooves on the surface of the missing seal. No trace of pigment was discerned on the Muru Ut Pata examples, but considering humid altiplano preservation conditions, we cannot rule out whether a fugitive pigment may once have been present.

Figure 4. Sealings from Muru Ut Pata (photos and drawings by Katharine M. Davis).

One sealing's motif is a geometric design with a quadripartite division of the space by two diagonal lines into triangular sections. Each section contains a T-shaped element originating at the center. The crossbars of the T curl down and inward, possibly referencing elements of the Formative period Yayamama iconographic tradition (Chavez Reference Chavez, Isbell and Silverman2002). The other sealing depicts a stylized head in profile facing to the right, wearing a rayed headdress. Considering profile-head motifs in Tiwanaku media, this figure likely represents a simplified variant of a turbaned human figure described as the arquero (Trigo Reference Trigo Rodriguez2013:7).

The Akapana East Signet Ring

Alan Kolata (Reference Kolata1993:167) reported a signet ring discovered in the 1988 excavations of the Akapana East 1 (AKE1) district at Tiwanaku, a residential area within the “moat” that surrounds the monumental core. Akapana East's residents had access to traditional Tiwanaku feasting wares and some imports from the eastern lowlands (Janusek Reference Janusek2004:111, 159). Janusek considered AKE1 to be an area of temporary dwellings and “dumping events” associated with ceremonial feasting. The signet ring, specimen TWK-6550, appears to be from AKE1 N7860 E5426 level 1, a context similar to Muru Ut Pata characterized by pits with dense midden and ash fill and large numbers of serving vessel fragments (Janusek Reference Janusek2004:143–144; Kolata Reference Kolata2021).

The signet ring, currently at the Tiwanaku site museum (CIAAAT), is a solid cylinder carved from camelid bone (Figure 5a). The polished flat surface forms a subsquare cartouche with a raised border (22 × 22 mm), framing a left-facing zoomorphic head in positive relief (Figure 5b). The figure's headdress has three upturned zoomorphic elements, which appear to represent heads of a quadruped, a raptor, and a fish. Behind the zoomorphic head is a slightly smaller opposite-facing head that could represent a human trophy head. Considering the zoomorphic profile-head, trophy head, and headdress elements, this figure resembles the “Tiwanaku Camelid Sacrificer” theme (Baitzel and Trigo Reference Baitzel and Trigo Rodríguez2019).

Figure 5. Signet ring TWK6550: (a) photo (CIAAAT; photo by David Trigo) and (b) design. (Color online)

Discussion

The Omo sealing, the Muru Ut Pata sealings, and the Akapana East signet ring represent a hitherto unstudied communicative technology. All have a similarly sized and shaped design cartouche. The sealings’ principal figures are intaglio reliefs, but the signet ring's principal figure appears in positive relief and would have produced negative relief images in sealings. Seals and sealings date to late in the Tiwanaku sequence, coinciding with the rebuilding of the capital's urban landscape and Tiwanaku's maximal peripheral expansion. This makes the use of seals concurrent with the height of Tiwanaku complexity and hegemony.

The context of the Omo sealing connects the messaging tradition inherent in seals to public architecture. Its discovery amid elite architectural debris could suggest its use on an architectural element of the temple like a door jamb or lintel. Seals were used to mark room dedications or closure in Old World examples (Zettler Reference Zettler1987), and a similar practice could imply that Tiwanaku emissaries were approving some architectural event at this remote location. The signet ring and the Muru Ut Pata sealings, however, were associated with residential discard in urban neighborhoods of the capital, suggesting other possibilities such as indicating ownership or marking products for trade. Sealing could be a “wet clay” parallel to the widespread post-firing engraving of symbols on serving ceramics by producers, intermediaries, or consumers (Goldstein Reference Goldstein, Isbell and Uribe2018:243–244; Korpisaari and Pärssinen Reference Korpisaari and Pärssinen2011:91–94).

Three of the four objects depict variants—possibly a human, a camelid, and a deer—of profile heads with headdresses, a theme that is common in Tiwanaku art and has been linked to elite-sponsored ritual production and performance. This thematic connection between the signet ring and the sealings raises intriguing questions about who did the sealing. Zoomorphic and human heads in Andean iconography were a way to legitimize social inequalities (Kolata Reference Kolata2003; Rowe Reference Rowe1967). The use of such motifs on seals to materialize elite authority or approval is one possibility. Signet rings could have extended authority of their wearers beyond their physical aspect, as did other elite-associated adornments in the southern Andes (Horta Reference Horta2016). Alternatively, non-elite identities and authorities, such as ayllus, moieties, or ethnicities, may have been symbolized, including through the geometric sealing.

The presence of a similar communicative technology across different urban neighborhoods at the capital could imply a more local identification, rather than an elite administrative intrusion. Akapana East 1 and Muru Ut Pata are not formalized administrative spaces; the presence of seal and sealings there speaks to the wider use of and access to this technology among communities with distinct social affinities, much like how the distribution of Indus Valley seals transcends social stratification (Possehl Reference Possehl2002). The presence of imported ceramics from the eastern Andean lowlands in Muru Ut Pata and Akapana East suggests perhaps expansive economic or social relationships for these residential groups.

Conclusion

The identification of a Tiwanaku signet ring seal and three sealings made by similar devices is the first demonstration of duplicative communication technology in the Central Andes. The use of seals and sealings in Tiwanaku culture suggests that specific authenticities and authorities tied to specific individuals or groups were transmitted over distance and time. Signet rings, the original digital medium, connected the symbolism of a Tiwanaku seal to the hand of a specific personage. A sealing with Tiwanaku-associated iconography in provincial public architecture suggests that an administrative apparatus disseminated authority through personalized symbols of power. However, seals and sealings found in domestic areas of the capital indicate that more research is needed on the role of seals in Tiwanaku society and politics.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Trigo, Patricia Palacios, Museo Contisuyo and the Ministerio de Cultura Peru DDC Moquegua, and three anonymous reviewers for helpful suggestions. This research was funded by the NSF Award 1067986 (Omo Temple), Harvard Field School at Tiwanaku, and PAPA (Muru Ut Pata).

Data Availability Statement

Data from the Omo and Muru Ut Pata projects are housed in the South American archaeology lab, UC San Diego, and Ursinus College. The artifacts described in the article are curated at Museo Contisuyo in Moquegua, Peru, and at the storage facility of CIAAAT in Tiwanaku, Bolivia.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.